Abstract

High tibial osteotomy (HTO) for varus knee osteoarthritis traditionally aims to overcorrect the mechanical tibiofemoral angle (mTFA) to become valgus. However, valgus overcorrection in HTO increases problems such as knee joint line abnormality, hinge fracture, and patellar height change. Thus, there is a trend to avoid overcorrection, but biomechanical basis for abandoning the overcorrection is lacking. From a dynamic perspective, medial-to-lateral knee joint load distribution during gait can be reflected by knee adduction moment (KAM), and the main purpose of HTO is to reduce the KAM increased during gait due to varus alignment. We tried to reveal the association between the KAM obtained from three-dimensional gait analysis and various static alignment parameters, including mTFA, measured from the standing whole limb anteroposterior radiograph and through this, to suggest a dynamically optimal target for HTO. When grouped according to the alignment by the interval of 1°, lower extremities with 3° to 8° of varus had greater KAM values than those with 0° to 5° of valgus. However, within groups of 0° to 5° of valgus, there were no significant differences. Therefore, the varus must be corrected to at least neutral alignment during HTO, but valgus overcorrection does not further reduce the KAM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to a systematic analysis, the global prevalence of knee osteoarthritis (OA) is 16.0% and its incidence is 203 per 10,000 person-years1. OA of the knee refers to the degenerative joint disease of the medial and lateral tibiofemoral and the patellofemoral compartments. It more frequently involves the medial tibiofemoral compartment than the others. The treatment of medial knee OA consists of operative managements such as alignment-correcting osteotomies and arthroplasty as well as conservative managements including laterally wedged shoes or insoles, toe-out gait, and valgus unloader knee braces2. Before treatment decisions, thorough radiographic assessments are necessary. Although expensive and time-consuming, dynamic study such as gait analysis is additionally performed in some orthopedic centers to provide biomechanical perspective to the patient’s knee. Among several variables measured during gait analysis, knee adduction moment (KAM) has widely received attention. The KAM is defined as the ground reaction force multiplied by its lever arm which is the perpendicular distance from the ground reaction force vector to the knee joint center2,3. The KAM acts to adduct the knee into a varus position4. It serves as a surrogate marker for the contact force and loading of the medial compartment5,6,7 and OA progression8. Moreover, several studies have reported that the KAM increases with the severity of knee OA4,9.

In a previous study from our group, the relationships between the KAM variables, namely, the KAM-time integral (KAM impulse) and the maximum KAM at stance phase measured with the three-dimensional (3D) gait analysis and the radiographic alignment parameters were analyzed. Both mechanical tibiofemoral angle (mTFA) and ankle joint line orientation (AJLO) relative to the ground independently explained the KAM. However, the study included only OA patients with varus knee alignment10. The relationship, therefore, could not be extrapolated to a general population or those with valgus knee alignment.

Because the medial compartment OA is known to aggravate with more varus alignment11, high tibial osteotomy (HTO) could be performed preferably in patients younger than 65 years old in order to unload the medial compartment. Miniaci’s and Dugdale’s methods have been traditionally used to preoperatively estimate the amount of correction needed in the HTO operation12. They usually locate the weight-bearing line at 62.5% of the tibial width, as measured from the medial to lateral edge of the tibial plateau, thus correcting the pre-existing varus alignment to 3° to 5° of mechanical valgus13. However, these preoperative surgical plannings were derived only from the radiological perspective based on static images. Although Yasuda et al. reported favorable long-term results in HTO with corrected mTFA of 12° to 16°14, valgus overcorrection might lead to problems such as knee joint line abnormality15, lateral hinge fracture16, leg length difference17, patellar height change18,19, patellar maltracking19,20, and decreased functional outcome15,20. Because of these problems, there is a trend to avoid overcorrection during HTO21,22,23,24, but there is a lack of dynamic perspective for abandoning the conventional overcorrection.

Equipped with the 3D gait analysis, the planning of HTO can also be approached from the biomechanical viewpoint. The KAM is reported to decrease following HTO25,26 and some researchers emphasized that the preoperative KAM could influence the outcome of the operation25 while others highlighted the effect of the postoperative alignment on the KAM26. Analysis of the KAM derived from subjects with different limb alignment would provide more insight to the amount of correction needed to achieve significant reduction in the KAM following the HTO.

In this study, our purpose was to analyze factors associated with the KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM values by reviewing the 3D gait analysis and radiographic alignment parameters of 500 randomly-selected volunteers from an urban area in Korea. Moreover, by categorizing each lower extremity according to its alignment, we aimed to compare the KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM according to the alignment groups. We intended to extend the understanding of the radiographic alignment parameters associated with the KAM and the relationship of the KAM with the degree of the lower limb alignment, providing background for the amount of alignment correction needed in the HTO.

Results

Population characteristics

The mean positive KAM-time integral, negative KAM-time integral, and maximum KAM were 0.13 ± 0.05 Nms/kg, 0.0039 ± 0.010 Nms/kg, and 0.36 ± 0.12 Nm/kg, respectively. The characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Differences of variables according to sex are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

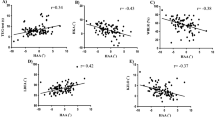

Correlation study between the KAM and other variables

The results of the correlation analyses between the KAM and other variables are shown in Table 2. mTFA had the strongest correlation with both the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM (r = 0.376 and 0.383, respectively) followed by AJLO (r = -0.258 and -0.269). The negative KAM-time integral had negative and positive correlation with mTFA (r = -0.095) and MPTA (r = 0.076), respectively.

Multiple regression analysis for the KAM variables

Sex, medial K-L grade, mTFA, MPTA, and AJLO comprised the final model for the positive KAM-time integral while mTFA and AJLO were included in the model for the maximum KAM. Both mTFA and AJLO independently explained the variance of the positive KAM-time integral the most while mTFA was the main explanatory parameter of the maximum KAM. The model for negative KAM-time integral included only mTFA (Table 3).

Positive KAM-time integral = 0.295 + (-0.009) x Sex + 0.012 × medial K-L grade + 0.006 × mTFA + (-0.002) x MPTA + (-0.003) x AJLO (R2 = 0.1917, adjusted R2 = 0.1874).

(1 and 2 for male and female, respectively).

Maximum KAM = 0.330 + 0.017 × mTFA + (-0.006) x AJLO (R2 = 0.1843, adjusted R2 = 0.1825).

Negative KAM-time integral = 0.0044 + (-0.0004) x mTFA (R2 = 0.0091, adjusted R2 = 0.0081).

Analysis according to mTFA by the interval of 1°

There was a tendency that the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM increased as mTFA increased (P < 0.001, Table 4). The post-hoc analysis of ANOVA of the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM of alignment groups are shown in Table 5. The positive KAM-time integral values of lower extremities of varus alignment groups with 3° ≤ mTFA < 8° were significantly greater than those of neutral or valgus alignment groups with -5° ≤ mTFA < 0°. Similar relationship was observed in the maximum KAM among those with 3° ≤ mTFA < 8° and -5° ≤ mTFA < 0°, except that the P-value of the post-hoc analysis of the maximum KAM between the alignment groups -1° ≤ mTFA < 0° and 5° ≤ mTFA < 6° was slightly greater than 0.05 (P = 0.088). Although the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM showed decreasing tendency in alignment groups of -5° ≤ mTFA < 0°, there was no significant difference of the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM within these groups (Table 5). There was no increasing tendency of the negative KAM as the amount of valgus increased (Table 4). Every alignment group with 3° to 7° of mTFA included more male than female extremities whereas female lower extremities were more prevalent in alignment groups with -4° to 0° of mTFA (P < 0.001).

Interobserver reliability test

Table 6 shows ICCs for each variable. Every coefficient value was greater than 0.8, implying good to excellent interobserver reliability27.

Discussion

In the analysis of 937 lower extremities of randomly-selected individuals of Seongnam, Korea, the positive KAM-time integral could be independently explained by sex, medial K-L grade, mTFA, MPTA, and AJLO. The variance in maximum KAM were independently explained by mTFA and AJLO. There was a tendency of increasing positive KAM-time integral and maximum KAM as the amount of varus alignment increased. When the lower extremities were categorized into alignment groups of 1° interval, lower extremities with 3° to 8° of varus had greater values of the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM than those with 0° to 5° of valgus. However, within the alignment groups of 0° to 5° of valgus, there was no significant difference in the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM.

In our study population, older participants and more male than female individuals had more varus limb alignment (Supplementary Table S1). In a landmark study conducted by Bellemans et al., the constitutional varus group were composed of older participants and its proportion of K-L grade 2 was higher than that of either the neutral or valgus alignment groups28. Colyn et al. reported increase in varus alignment during the arthritic progression when comparing consecutive full-length X-rays of the same patients over mean 2 years29. Despite the cross-sectional nature of our study, lower extremities with varus alignment belonged more to the older individuals, which was in agreement with the progression of varus alignment as one ages. Interestingly, significantly more male lower extremities belonged to the varus alignment group. Male lower extremities had greater mean varus alignment (1.70° vs. 0.61°) and had lower mean MPTA (85.8° vs. 86.6°) than those of female while there was no significant difference in LDFA between the sexes. This may be the reason why male population had positive correlation with the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM. Moreover, the final model for the positive KAM-time integral in the multiple regression analysis also included male sex as an independent explanatory variable though its net contribution was less than 1%. The trends that there are more males than females with varus limb alignment due to the smaller MPTA in males have been reported in a healthy Korean population30 and other ethnic groups as well28,31. Hueter-Volkmann law partly explains this phenomenon30,32 because men are tended to be more physically active than women in younger populations.

mTFA and AJLO had the strongest correlation with the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM in the correlation study. The following multiple regression analyses revealed the quantitative relationship between the positive KAM-time integral and sex, medial K-L grade, mTFA, MPTA, and AJLO. Although they only explained less than 1% of the variance of the positive KAM-time integral when other variables were included, grade of OA in the medial compartment and tibia vara increased the positive KAM-time integral but not the maximum KAM. The KAM-time integral was noted to be more sensitive at distinguishing between K-L grades than the maximum KAM9. However, when backward eliminations were performed from the final model for the positive KAM-time integral, mTFA and AJLO were the main explanatory variables. This relationship between the KAM variables and mTFA and AJLO was demonstrated in the previous study of our group which only included patients with varus knee OA10. Our study extends this relationship to a general population including participants with valgus limb alignments. The correlation between the maximum KAM and the ankle inversion moment was reported33,34. The varus position of the ankle in the stance phase of the gait cycle produces adduction force to the knee joint probably by laterally shifting the center of the knee joint. This association provides biomechanical grounds for laterally wedged shoes or insoles as means of conservative management for the medial knee OA. Upon performing HTO, preoperative lateral inclination of the ankle joint is reported to change into a less laterally-inclined or neutral orientation postoperatively35,36,37. Therefore, HTO could have a double positive effect in reducing the KAM by decreasing mTFA and increasing AJLO. The magnitude of R2 values is less than 20% in all of our multiple regression analyses. There may be other factors not considered in our study such as foot progression angle, and walking speed34,38,39. Since mechanical axis was reported to account for about 50% of the variation in the peak KAM in patients with OA38, R2 values seem too small even if we had considered other factors which are known to influence the KAM. This difference might be attributed to the fact that randomly-selected volunteers instead of known OA patients were enrolled in our study. The correlation coefficient between alignment and the maximum KAM was 0.383 in our study, smaller than those calculated from studies with knee OA patients (0.75138. 0.5926, and 0.54310). Coronal tibiofemoral translation did not have significant correlation with the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM in our study probably due to relatively competent collateral ligament status in general but not osteoarthritic population setting.

The positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM of lower extremities with 3° to 8° of varus were greater than those of 0° to 5° of valgus alignment, respectively. It can be inferred that in order to reduce the KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM significantly, the amount of correction should at least reach neutral alignment when performing HTO. Wada et al., comparing the low and high adduction moment group that underwent HTO, advocated valgus overcorrection to prevent varus recurrence26. In a 10- to 15-year follow-up study, Yasuda et al. addressed that mTFA of 12° to 16° should be attained to ensure good long-term outcome14. However, there was no significant difference of the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM within the alignment groups of 0° to 5° of valgus in our study, implying that valgus overcorrection seems to offer no additional benefit in reducing the KAM values. According to a meta-analysis investigating the amount of knee adduction moment loss after medial open wedge HTO, KAM after the operation decreased to 60% of the preoperative level. The authors also reported that there was no significant association between alignment correction amount and difference in the KAM before and after the operation40. Our findings support their conclusion though our study could only compare the KAM values of lower extremities cross-sectionally. While the alignment group of 6° to 7° of valgus showed significant difference in the positive KAM-time integral with alignment groups of 0° to 5° and 7° to 8° of valgus, there was only one limb with the 6° to 7° valgus alignment, which could be interpreted as bias due to small sample size in the group. In conjunction with recent trend to avoid valgus overcorrection in HTO21,23,24 which might cause problems such as knee joint line abnormality15, lateral hinge fracture16, and patellar maltracking19,20, our study advocates correction to at least neutral alignment when performing HTO but excessive valgus correction provides no significant reduction in the KAM values. Further studies are needed to validate whether this amount of reduction in the KAM values has clinically significant effects. Moreover, we look forward to clinical studies comparing the postoperative KAM and functional outcomes of correction to neutral and valgus-corrected alignments after HTO.

Peak knee joint moments are reported to be strongly correlated with both peak medial and lateral knee joint contact forces in knees with valgus malalignment5. The negative KAM-time integral among the alignment groups did not show increasing trend as the amount of valgus increased. This might be due to the small absolute value of the negative KAM-time integral and to the relatively small number of participants with valgus alignment. Moreover, only 0.8% of the variations of the negative KAM were explained by the mechanical alignment in the multiple regression analysis. Further research enrolling more subjects with valgus alignment would reveal the relationship between the amount of valgus and the negative KAM-time integral.

Our study has several limitations. First, though we explored the relationship between the KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM and the radiographic alignment variables, no causality relation could be directly inferred due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. Second, because randomly-selected volunteers were enrolled in the study, our findings may not be directly applicable to the patients with knee OA whose cartilage status should also be taken into account when deciding the correction amount in HTO41. Third, R2 values in our multiple regression analyses were too small. Inclusion of more factors such as foot progression angle, stride length, and walking speed might have improved the explanatory power of the regression model. Fourth, there were some inherent problems during radiographic assessments because the study was retrospective. Since radiographs such as the lateral and the Rosenberg view were not taken, K-L grade of tibiofemoral joint of each knee could be assessed merely from the full-lower limb standing anteroposterior (AP) radiograph, which could have underestimated the degree of OA. Moreover, in some radiographs, X-ray beam was not orthogonal to the tibiofemoral joint space, which made it difficult to assign the K-L grades properly and measure angles for some lower extremities.

In spite of its limitations, our study presented the associations between the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM and radiographic alignment variables, namely, mTFA and AJLO in randomly-selected individuals. Moreover, we demonstrated the difference of the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM in lower extremities with 3° to 8° of varus and 0° to 5° of valgus while there was no significant difference of the KAM within the latter alignment groups. We believe these findings would provide biomechanical evidence to correction to at least neutral alignment when performing HTO while valgus overcorrection provides no additional benefit in reducing the KAM.

Methods

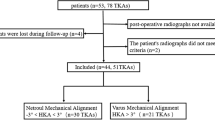

Participants

This study was performed by retrospectively reviewing the data from a previously-conducted prospective cohort study42. 500 participants with the age of 10 to 75 years were randomly selected from the city of Seongnam, Gyeonggi province, South Korea. All subjects gave informed consent about data collection. They underwent 3D gait analysis and standing full-lower limb AP radiograph was taken for each individual from February 2016 to December 2019. The present study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (B-2308-847-102) and was performed according to the international ethical guidelines of human subject research.

Of 1000 lower extremities from total 500 participants, 937 were included in the final analysis. Since the position of the patella relative to the center of the knee joint could substantially affect radiographic parameters such as mTFA, medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA), and mechanical lateral distal femoral angle (LDFA)43, quality of each full-lower limb AP radiograph was evaluated in relation to the degree of patellar rotation relative to the adjacent femur. The relative amount of patellar rotation was categorized into 4 grades in the following way. When the patella was located at the center of the tibiofemoral joint, it was defined as "patella facing forward" or grade 0. If the edge of the patella crossed either the medial or lateral margin of the adjacent femur, it was termed grade 3 internal or external rotation, respectively. Grade 1 was assigned to those with only slight rotation from the center and grade 2 to those in which the patellar margin was just on but not past the boundary of the adjoining femur. 57 lower extremities with grade 3 patellar rotation were excluded from the analysis. Gait analysis data from 3 participants (6 lower extremities) were excluded due to marker mismatch error.

Anthropometric parameters

Age, sex, and anthropometric parameters such as height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were collected from each participant.

Radiographic measurements

All full-lower limb standing AP radiograph images were uploaded to a picture archiving and communication system (PACS), and radiographic measurements were conducted with the PACS softwares (INFINITT, Seoul, Korea and Medixant. RadiAnt DICOM Viewer. Version 2023. 1.).

The degree of knee OA in the medial and lateral compartments of the tibiofemoral joint was evaluated using the K-L grade. For fear of ambiguity of the original definition and interobserver disagreement, we categorized less than 50% narrowing of the original joint space as K-L grade II and more than 50% narrowing of the joint space as K-L grade III10.

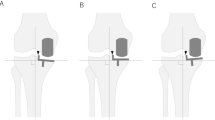

The following radiographic alignment parameters were measured for each lower extremity in the standing full-lower limb AP radiograph: mTFA, MPTA, mechanical LDFA, knee joint line orientation (KJLO) relative to the horizontal plane, AJLO to the horizontal plane, and joint line convergence angle (JLCA). The mTFA, defined as the angle between the mechanical axis of the femur and the tibia, was measured in the following manner using the PACS softwares. The mechanical axis of the femur was depicted as the line from the center of the femoral head to the center of the intercondylar notch of the femur. Initially, a closest-fit circle was drawn to match the margin of the femoral head. The femoral head center was then determined as the intersection of the two crossing lines each with the length of the diameter of the circle. The mechanical axis of the tibia was referred to as the line connecting the center of the intercondylar eminences of the tibial plateau and the center of the talar dome. Positive and negative values of the mTFA were assigned to the knees with varus and valgus mechanical alignments, respectively. The MPTA was measured as the medial angle between the mechanical axis of the tibia and the tangential line to the tibial plateau. The mechanical LDFA was measured as the lateral angle between the mechanical axis of the femur and the tangential line to both the medial and lateral femoral condyles. The KJLO was measured in the following two steps. Initially, the midline of the tangential line to the tibial plateau and the tangential line to the femoral condyles was drawn. Then, the angle between this midline and a horizontal line parallel to the ground was defined as the KJLO. Positive and negative values were given when the midline was inclined to the medial and lateral sides of the corresponding tibiofemoral joint, respectively. The AJLO was defined as the angle between the tangential line to the talar dome and a horizontal line parallel to the ground. Positive and negative values were given when the tangential line was inclined to the medial and lateral sides of the corresponding tibiotalar joint, respectively. The JLCA was measured as the angle between the tangential line to the tibial plateau and the tangential line to the femoral condyles (Fig. 1). Positive and negative values were given when the intersection of the lines was located medial and lateral to the joint, respectively.

Measurement of mTFA, MPTA, LDFA, KJLO, AJLO, JLCA, and tibiofemoral translation. (a) mTFA (b) MPTA (c) LDFA (d) KJLO (e) AJLO (f) JLCA (g) Tibiofemoral translation. mTFA mechanical tibiofemoral angle, MPTA medial proximal tibial angle, LDFA lateral distal femoral angle, KJLO knee joint line orientation, AJLO ankle joint line orientation, JLCA joint line convergence angle.

Tibiofemoral translation was measured using coronal tibiofemoral subluxation. It is known to impair the load transmission across the medial compartment of the knee44 and to be caused by a difference in the medial and lateral soft tissue laxity45. It is defined as the distance between a line perpendicular to the ground and passing through the most lateral point of the lateral femoral condyle and a line perpendicular to the ground and passing through the most lateral point of the lateral tibial condyle. This distance was normalized by dividing it with the width of the corresponding tibial plateau44 (Fig. 1). Positive and negative values were conferred when the lateral-most point of the femoral condyle was located medial and lateral to the lateral-most point of the tibial plateau, respectively.

Interobserver reliability was tested by two orthopaedic surgeons with 8 and 5 years of clinical experience in the orthopaedic department. To achieve adequate power, 33 lower extremities were randomly selected from the study population and assigned to each surgeon. They independently evaluated the K-L grade and measured the radiographic alignment parameters, being blinded to each other’s measurements.

3D gait analysis

Participants underwent 3D gait analysis using a motion analysis system (Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, California, USA) with 10 cameras at 120 frames per second and two force plates. Photo-reflective skin markers in accordance with Helen marker set were installed by an operator having 9 years of experience in the field. The participants walked barefoot on a ten-meter-long track at their self-selected speed after 10 walking trials. Joint moments were calculated using the inverse dynamic model and the global coordination system42. The values of the KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM in the stance phase were obtained. Although there can be the second peak KAM as well as the first peak KAM, the appearance of the second peak KAM is reported to be inconsistent38. Therefore, only the maximum KAM was used in our study. The KAM-time integral or KAM impulse which was reported to be more sensitive at distinguishing disease severities than the maximum KAM9 was calculated by integrating the KAM relative to time during the stance phase, representing accumulation of the KAM according to time. The positive and negative KAM-time integral values were calculated separately to represent the adduction and abduction moment, respectively46. Average values of 3 repetitive measurements of both the KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM were used in the analysis. The KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM were calculated in the units of N·m·s/kg and N·m/kg, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted first to depict the population characteristics. Normality was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Inferential statistical analyses were then performed using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) and t-tests or Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables which belong to each alignment category by the interval of 1° of mTFA and either sex, respectively. Subgroup analyses for ANOVA were performed using Bonferroni post-hoc test. The correlation analyses between the KAM values and other variables were performed to obtain Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient. Interobserver reliability was tested with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) with the assumption of single measurement and absolute agreement. The multiple linear regression analyses for the KAM values were conducted with variables which were significantly related to the KAM values in the correlation analyses. Then, backward elimination of variables was performed so that only variables with independent explanatory ability wound remain in the final model. To point out variables with the highest explanatory value, more backward eliminations from the final model for the positive KAM-time integral and the maximum KAM were conducted. Multi-collinearity was evaluated with variance inflation factors (VIFs). All statistical analyses were done using R software (version 4.2.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), RStudio 2023.12.0 + 369 “Ocean Storm” Release (33206f75bd14d07d84753f965eaa24756eda97b7, 2023-12-17) for Windows. In every analysis, P-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available because the study participants did not consent to public sharing of their data. Moreover, the institutional review board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital did not approve sharing of the participants’ data publicly. The data are available from the corresponding author only upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital.

References

Cui, A. et al. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 29–30, 100587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100587 (2020).

Reeves, N. D. & Bowling, F. L. Conservative biomechanical strategies for knee osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 7, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2010.212 (2011).

Foroughi, N., Smith, R. & Vanwanseele, B. The association of external knee adduction moment with biomechanical variables in osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Knee 16, 303–309 (2009).

Sharma, L. et al. Knee adduction moment, serum hyaluronan level, and disease severity in medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis. Arthr. Rheum. 41, 1233–1240 (1998).

Holder, J. et al. Peak knee joint moments accurately predict medial and lateral knee contact forces in patients with valgus malalignment. Sci. Rep. 13, 2870. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30058-4 (2023).

Kutzner, I., Trepczynski, A., Heller, M. O. & Bergmann, G. Knee adduction moment and medial contact force–facts about their correlation during gait. PLoS One 8, e81036. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081036 (2013).

Zhao, D. et al. Correlation between the knee adduction torque and medial contact force for a variety of gait patterns. J. Orthopaed. Res. 25, 789–797 (2007).

Miyazaki, T. et al. Dynamic load at baseline can predict radiographic disease progression in medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 61, 617–622. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.61.7.617 (2002).

Kean, C. O. et al. Comparison of peak knee adduction moment and knee adduction moment impulse in distinguishing between severities of knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Biomech. 27, 520–523 (2012).

Lee, N.-K. et al. Relationship between radiographic measurements and knee adduction moment using 3D gait analysis. Gait Posture 90, 179–184 (2021).

Sharma, L. et al. Varus and valgus alignment and incident and progressive knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1940–1945 (2010).

Kang, B. Y., Lee, D. K., Kim, H. S. & Wang, J. H. How to achieve an optimal alignment in medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy?. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 34, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43019-021-00130-2 (2022).

Rossi, R., Bonasia, D. E. & Amendola, A. The role of high tibial osteotomy in the varus knee. JAAOS J. Am. Acad. Orthopaed. Surg. 19, 590–599 (2011).

Yasuda, K., Majima, T., Tsuchida, T. & Kaneda, K. A ten- to 15-year follow-up observation of high tibial osteotomy in medial compartment osteoarthrosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 282, 186–195 (1992).

Kim, J. S. et al. Excessively increased joint-line obliquity after medial opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy is associated with inferior radiologic and clinical outcomes: What is permissible joint-line obliquity. Arthroscopy 38, 1904–1915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2021.11.004 (2022).

Lee, S. S., Celik, H. & Lee, D. H. Predictive factors for and detection of lateral hinge fractures following open wedge high tibial osteotomy: Plain radiography versus computed tomography. Arthroscopy 34, 3073–3079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2018.06.041 (2018).

Lee, O. S., Ahn, S. & Lee, Y. S. Comparison of the leg-length change between opening- and closing-wedge high tibial osteotomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Knee Surg. 32, 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1641176 (2019).

Bin, S. I., Kim, H. J., Ahn, H. S., Rim, D. S. & Lee, D. H. Changes in patellar height after opening wedge and closing wedge high tibial osteotomy: A meta-analysis. Arthroscopy 32, 2393–2400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2016.06.012 (2016).

Gaasbeek, R., Welsing, R., Barink, M., Verdonschot, N. & van Kampen, A. The influence of open and closed high tibial osteotomy on dynamic patellar tracking: A biomechanical study. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 15, 978–984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-007-0305-0 (2007).

Lee, S. S. et al. Predictive factors for patellofemoral degenerative progression after opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Arthroscopy 35, 1703–1710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2019.01.032 (2019).

Heijens, E., Kornherr, P. & Meister, C. The coronal hypomochlion: A tipping point of clinical relevance when planning valgus producing high tibial osteotomies. Bone Joint J. 98-b, 628–633. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.98b5.33394 (2016).

Martay, J. L. et al. A preliminary modeling investigation into the safe correction zone for high tibial osteotomy. Knee 25, 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2017.12.006 (2018).

Kuriyama, S. et al. Large medial proximal tibial angles cause excessively medial tibiofemoral contact forces and abnormal knee kinematics following open-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon) 80, 105190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2020.105190 (2020).

Atkinson, H. F. et al. High tibial osteotomy to neutral alignment improves medial knee articular cartilage composition. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 30, 1065–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06516-9 (2022).

Prodromos, C. C., Andriacchi, T. P. & Galante, J. O. A relationship between gait and clinical changes following high tibial osteotomy. JBJS 67, 1188–1194 (1985).

Wada, M. et al. Relationship Between Gait and Clinical Results After High Tibial Osteotomy. Clin. Orthopaed. Relat. Res. 354, 180–188 (1998).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 (2016).

Bellemans, J., Colyn, W., Vandenneucker, H. & Victor, J. The Chitranjan Ranawat award: is neutral mechanical alignment normal for all patients? The concept of constitutional varus. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 470, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-011-1936-5 (2012).

Colyn, W. et al. Changes in coronal knee-alignment parameters during the osteoarthritis process in the varus knee. J. Isakos 8, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisako.2022.12.002 (2023).

Hwang, D. et al. Age and sex differences in coronal lower extremity alignment in a healthy Asian population. Knee 45, 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2023.09.009 (2023).

Khattak, M. J., Umer, M., Davis, E. T., Habib, M. & Ahmed, M. Lower-limb alignment and posterior tibial slope in Pakistanis: A radiographic study. J. Orthopaed. Surg. 18, 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/230949901001800105 (2010).

Stokes, I. A. Mechanical effects on skeletal growth. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact 2, 277–280 (2002).

Wang, J. W., Kuo, K. N., Andriacchi, T. P. & Galante, J. O. The influence of walking mechanics and time on the results of proximal tibial osteotomy. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 72, 905–909 (1990).

Andrews, M., Noyes, F. R., Hewett, T. E. & Andriacchi, T. P. Lower limb alignment and foot angle are related to stance phase knee adduction in normal subjects: A critical analysis of the reliability of gait analysis data. J. Orthop. Res. 14, 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.1100140218 (1996).

Lee, K. M. et al. Changes of knee joint and ankle joint orientations after high tibial osteotomy. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 23, 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.11.001 (2015).

Kim, J. G., Suh, D. H., Choi, G. W., Koo, B. M. & Kim, S.-G. Change in the weight-bearing line ratio of the ankle joint and ankle joint line orientation after knee arthroplasty and high tibial osteotomy in patients with genu varum deformity. Int. Orthopaed. 45, 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04799-0 (2021).

Tseng, T. H., Wang, H. Y., Tzeng, S. C., Hsu, K. H. & Wang, J. H. Knee-ankle joint line angle: a significant contributor to high-degree knee joint line obliquity in medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. J. Orthop. Surg. Res 17, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-02976-y (2022).

Hurwitz, D. E., Ryals, A. B., Case, J. P., Block, J. A. & Andriacchi, T. P. The knee adduction moment during gait in subjects with knee osteoarthritis is more closely correlated with static alignment than radiographic disease severity, toe out angle and pain. J. Orthop. Res. 20, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0736-0266(01)00081-x (2002).

Andriacchi, T. P., Ogle, J. A. & Galante, J. O. Walking speed as a basis for normal and abnormal gait measurements. J. Biomech. 10, 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(77)90049-5 (1977).

Kim, J.-H., Kim, H.-J., Celik, H., Kim, J.-H. & Lee, D.-H. Change in adduction moment following medial open wedge high tibial osteotomy: A meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 20, 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2472-9 (2019).

Jakob, R. P. & Jacobi, M. Die zuklappende Tibiakopfosteotomie in der Behandlung der unikompartimentären Arthrose. Der Orthopäde 33, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-003-0600-5 (2004).

Park, G., Lee, K. M. & Koo, S. Uniqueness of gait kinematics in a cohort study. Sci. Rep. 11, 15248. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94815-z (2021).

Burghardt, R. D., Hinterwimmer, S., Bürklein, D. & Baumgart, R. Lower limb alignment in the frontal plane: analysis from long standing radiographs and computer tomography scout views: An experimental study. Arch. Orthopaed. Trauma Surg. 133, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-012-1635-z (2013).

Ogawa, H., Matsumoto, K. & Akiyama, H. Coronal tibiofemoral subluxation is correlated to correction angle in medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 26, 3482–3490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-4948-9 (2018).

Greif, D. N., Epstein, A. L., Hodgens, B. H., Jose, J. & Baraga, M. G. Current measurement strategies of coronal tibiofemoral subluxation: A systematic review of literature. Am. J. Roentgenol. 216, 1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.20.23503 (2021).

Hinman, R. S., Hunt, M. A., Simic, M. & Bennell, K. L. Exercise, gait retraining, footwear and insoles for knee osteoarthritis. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 1, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-012-0004-8 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Misun Yoo for helping with the processing of 3D gait analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S.K. contributed to radiographic measurements, data analysis, data interpretation, and drafting of the work. N.L. contributed to the design of the work, data analysis and data interpretation. K.M.L. contributed to data acquisition. C.B.C. contributed to the design of the work, data acquisition, and data interpretation. S.K. contributed to data interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, K.S., Lee, NK., Lee, K.M. et al. Correction to at least neutral alignment during high tibial osteotomy is sufficient in reducing the knee adduction moment. Sci Rep 15, 11490 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80161-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80161-3