Abstract

The advent of the Transformer has significantly altered the course of research in Natural Language Processing (NLP) within the domain of deep learning, making Transformer-based studies the mainstream in subsequent NLP research. There has also been considerable advancement in domain-specific NLP research, including the development of specialized language models for medical. These medical-specific language models were trained on medical data and demonstrated high performance. While these studies have treated the medical field as a single domain, in reality, medical is divided into multiple departments, each requiring a high level of expertise and treated as a unique domain. Recognizing this, our research focuses on constructing a model specialized for cardiology within the medical sector. Our study encompasses the creation of open-source datasets, training, and model evaluation in this nuanced domain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Heart Report 20231 by the World Heart Federation, More than half a billion people around the world continue to be affected by cardiovascular diseases(CVD), and in 2021, 20.5 million individuals died from CVD. This represents a significant increase compared to the 12.1 million CVD deaths recorded in the 1990s. Moreover, according to Korean statistics, there has been an increasing trend in heart-related mortality among Koreans from 2011 to 20212. As these statistics demonstrate, predicting and managing CVD is extremely important in medicine. In this situation, analyzing medical data effectively has become essential, and the quantity of data to be analyzed is also increasing.

Recent advancements in Natural Language Processing (NLP) within the field of machine learning have been significant, and they can play a crucial role in handling the vast amount of cardiology related medical data. The introduction of the Transformer3 model can be seen as the primary catalyst for this swift progress. Upon its introduction, the Transformer model updated the state of the art in natural language processing and quickly became the dominant research paradigm. This success led to the creation of derivative models, notably BERT4 and GPT5–]7.

These Transformer-based models have been applied across various specialized fields, including medical, where they have achieved significant success. The success in the medical domain has indicated the potential for fundamentally changing the approach to medical language8. A prominent example of success in the medical field is BioBERT. In BioBERT, the model undergoes pre-training on a large medical corpus and is then fine-tuned through a fine-tuning phase for downstream tasks, demonstrating high performance. This led to the emergence of many more specialized medical language models9.

The success of these medical models is undeniable, yet their approach of treating the medical field as a singular domain diverges from the actual medical system. In contrast to the methodology of these language models, modern medical is characterized by individual specialists managing specific departments, necessitating extensive time and effort to become an expert within a particular department. This highlights the fact that each department is a specialized field with a vast amount of information to be handled. With this consideration, we developed HeartBERT, a language model optimized for cardiology.

Our research builds upon the success of existing medical language models, focusing on data collection, processing, and model training. However, unlike previous medical language models, models specialized in segmented areas face challenges in applying existing benchmarks. Due to the absence of appropriate benchmarks, it was challenging to evaluate the model. Consequently, we created a dataset specifically designed to assess models with expertise in segmented areas. We then conducted actual evaluations on this specifically designed dataset and compared the results.

In summary, our study presents the following contributions:

-

1.

We propose a new perspective for building medical language models. By segmenting the medical domain and constructing language models specialized for these segmented areas, our approach enables high performance even with smaller language models.

-

2.

Constructing datasets for specialized areas is a challenging problem. We present methods for building datasets tailored to specific areas of medicine using multiple data sources.

-

3.

Specialized models are not only difficult to train but also challenging to evaluate due to the lack of benchmarks. In this study, we explore methods for generating benchmarks without human intervention.

-

4.

This research constructs datasets, models, and benchmarks for cardiology. The methods we propose can be easily applied to other departments, making them highly scalable.

Related work

The recent achievements in natural language processing can be considered a triumph of the Transformer and its derivative models, which have introduced a paradigm shift by significantly altering how data is leveraged. Notably, the Transformer model enabled parallel processing, setting it apart from its predecessors. This advancement significantly boosted training efficiency using Graphic Processing Units (GPU), making it feasible to train large models on extensive datasets. Additionally, the introduction of pre-training has allowed for the utilization of vast amounts of unlabeled data in training. Pre-training involves masking parts of sentences and then training the model to predict the original tokens or to predict subsequent tokens. Models that have undergone pre-training gain a comprehensive understanding of language, which leads to enhanced performance on downstream tasks.

Several studies suggest that models pre-trained on domain-specific corpora gain a deeper understanding of that particular domain. Among these studies, BioBERT stands out for training a language model on a medical corpus. BioBERT demonstrated improved performance on medical-related texts by pre-training the model on a large medical corpus compared to general models. Beyond BioBERT, numerous specialized medical models like Med-BERT10 have been developed, continuing with the recent trend of foundation models11. Studies such as Meditron12, PMC-Llama13, and ChatDoctor14 have aimed to create medical-specialized foundation models by fine-tuning general foundation models on medical corpora. These biomedical-specific models have demonstrated superior performance compared to general models in various tasks such as biomedical Named Entity Recognition (NER)15, relation extraction, and question answering.

These studies have all focused on training a single model across the entire medical field. Given the breadth and complexity of medical language, training one model with all medical information can be inefficient. In our research, diverging from previous studies, we constructed models specialized in segmented departments, thereby creating a model that can achieve higher performance within a single department. OThis approach is exemplified by CardioBERTpt16, which trained six checkpoint models on electronic health records related to cardiology, demonstrating superior results in downstream tasks compared to existing models. However, CardioBERTpt faces challenges in utilizing datasets or retraining models due to its reliance on closed hospital data.

In the study by Naga et al.17, BERT was also fine-tuned for CVD diagnosis tasks, demonstrating high performance. However, the study did not address the construction of large-scale datasets for pre-training. In our research, we constructed datasets from open-source databases, enabling unrestricted access to data and facilitating easy application to fields other than cardiology. Additionally, it addresses methods for constructing benchmark datasets to evaluate models in such specialized domains.

Method

Following the introduction of models such as Transformer, BERT, and GPT, research in language models has shifted its focus more towards the data aspect rather than structural studies of the models themselves. The significance of data in language models is paramount, and this importance is magnified in the case of specialized models. The specialization of the model is determined by the characteristics of the training dataset. In the “Data collection” section, we discuss the process of collecting and processing data for training a cardiology-specialized language model. Section “Model” addresses the construction and training methodology of the model.

Data collection

Selecting the appropriate data source significantly impacts the model’s performance. The majority of the data we used for training was collected from PubMed. PubMed is a database that provides abstracts of research papers related to life sciences, biomedical fields, health psychology, and health and welfare. The data retrieved from PubMed are authored by medical professionals and undergo a peer review process before publication, ensuring high reliability and expertise. However, since PubMed does not provide information on specific medical departments, additional work was required to exclusively extract cardiology-related data.

We focused on selecting relevant queries for the PubMed API used in data collection. These queries needed to be specific to cardiology and distinct from other departments. Initially, we used cardiology-related journals as queries for the API. We compiled a list of journals to be used as queries based on the Scientific Journal Rankings (SJR). The SJR provides ranking information for journals across various categories. From the SJR’s “Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine” category, we used journals ranked from 1st to 300th as our queries. This includes all journals from Q1 to Q3, as well as some Q4 journals. The number of selected journals can vary according to the researcher’s intent. If more data is desired, journals across all ranks can be included. Alternatively, if the focus is on collecting only high-impact data, journals ranked from 1st to 100th may be chosen.

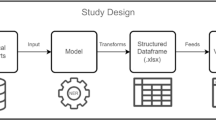

The process of extracting a cardiology-specialized dataset. The “Query” block represents the queries used in this study. We selected journal names related to cardiology provided by SJR (SJR-journal) and glossaries from Aiken, NIH, and the Texas Heart Institute as our queries. These selected queries were then used as inputs for the APIs provided by the databases. The API results filtered data from the databases relevant to the queries. The “Data Source” block represents the databases used in this study, which are PubMed and Wikipedia. “Dataset ver2” denotes the version of the collected data. The dataset consisting of only PubMed data is referred to as version 1, while the dataset that integrates both PubMed and Wikipedia data is referred to as version 2.

In addition, glossaries were utilized as queries. Terms listed in a cardiology glossary can also be said to well represent the cardiology. However, some terms are used not only in cardiology but also in general medical fields. For example, while X-ray is listed in the cardiology glossary, it is difficult to consider it a term exclusive to cardiology. Using such queries for data collection can result in the inclusion of data from other departments, diluting the specificity of the dataset. We manually removed these general terms. The refined glossaries were then used as queries for data collection, and in this study, we utilized cardiology glossaries provided by Aiken Physicians18, National Institutes of Health (NIH)19, and The Texas Heart Institute20.

The second Data Source we utilized is Wikipedia, an internet encyclopedia that can be edited by anyone and is managed through collaboration. Although it may not have the same level of reliability as PubMed, due to the lack of a formal verification process, Wikipedia covers a broader range of topics compared to PubMed, which focuses solely on scholarly papers. This inclusion enhances the diversity of the data for training purposes.Wikipedia provides information about categories and subcategories for classification. We found that Wikipedia has a top-level category called “Cardiology,” which we used as the primary category. Starting with the “Cardiology” category, we navigated through the subcategories provided by Wikipedia to collect related articles. Additionally, we used the glossary we compiled as queries for the Wikipedia API to gather further relevant data. Figure 1 illustrates the overall data collection process.

Articles collected from Wikipedia based on Category and glossary are comprised of various sections including title, text, references, among others. Among these sections, there are those unnecessary for training, which necessitates their removal. We excluded sections such as ’community’, “See also”, “References”, “Sources”, ’External links’, ’Journals’, ’Association’, “organizations”, ’publications’, ’List of’, and ’Further reading’ from the collection process, as they were not essential for training. Additionally, sections ending with “-ists” that describe researchers were also excluded from the training dataset.

However, depending on the circumstances, it may be challenging to construct a dataset solely based on journal names or a glossary. In such cases, keywords can be extracted from the initially collected data and applied to a second round of the data collection process. This method is expected to be particularly suitable for departments with limited data. In the case of cardiology, given the field’s active research within the medical domain, it was determined that a sufficient amount of data could be gathered through the initial extraction process alone, and thus, additional keyword extraction efforts were not undertaken.

All data was collected using Python and the Python library urllib. The urllib library was used to call the PubMed and Wikipedia APIs, and the resulting data was processed using Python libraries Json and Pandas. The data was collected between March 2023 and August 2023.

Model

Studies such as BioBERT have demonstrated that training language models on documents from a specific field leads to better performance in that area. Building upon this foundation, we have taken a step further by developing a model specialized exclusively in cardiology, thus achieving greater specialization. This approach aligns with the actual structure of the medical system. Most specialists focus on a single field, as it is challenging for one specialist to cover more than one area without compromising expertise. We applied this same logic to the development of our language model.

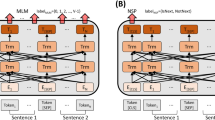

In this study, we employed a BERT-based model. We trained BERT on documents related to cardiology to construct a specialized HeartBERT, aiming for specialized performance in cardiology-related tasks. Our models are characterized by three components: size, training approach, and the type of data used. Two sizes were used: BERT-Tiny (14.5M)21 and BERT-Base (109M), with no distillation applied to BERT-Tiny due to the absence of a reference model.

We employed two training approaches: the continual and scratch methods. In the continual method, pre-trained Tiny-BERT and BERT-base models were further trained with our dataset, including tokenizer and model updates. In the scratch method, we started with the architecture of Tiny-BERT and BERT-base, initialized the weights, and then trained from scratch with the cardiac dataset. Moreover, our models can be distinguished based on the datasets used. We divided the collected dataset into three versions, with each ascending version increasing in data volume and diversity. Version 1 (5.2 GB, 843M tokens) utilized PubMed data, while Version 2 (5.6 GB, 912.5M corpus) incorporated additional data from a Wikipedia. The newly added dataset in Version 2 is 0.4GB, which is significantly smaller compared to the 5.2 GB of Version 1. This difference can be attributed to the characteristics of each database. PubMed, used in Version 1, contains a substantial amount of heart-related data and is relatively easy to filter, whereas Wikipedia has fewer articles specifically related to the heart. However, because the two databases cover different topics, Version 2 was created to observe the performance changes of the model due to the diversity of the data. In each data version, 80% was used for training, and the remaining 20% for model evaluation.

Based on the components of the model described above, the model’s name is represented in the format “size-training approach-data version”. For example, a Tiny-BERT model trained using the scratch method and data from Version 1 would be denoted as “Tiny-scratch-ver1”. We trained a total of eight models utilizing two model sizes (BERT-Tiny, BERT-base), two training methods (continual, scratch), and two data versions. All models were pre-trained using the masking approach.

Training

The training process begins with pre-training using a Masking approach on the collected free text. Masking is the most representative method for pre-training models like BERT. It involves substituting some tokens in a sentence with a “[Mask]” token or another random token, after which the model is trained to restore these to their original tokens. This allows the model to develop a deeper understanding of language without labeled data. The pre-trained model was subsequently fine-tuned for the downstream task. In this study, NER was selected as the downstream task, and the model was trained to classify a total of nine different entities. Figure 2 shows our overall training process.

The training was optimized using the Adam22 optimizer with the following parameters : \(\beta\)1 = 0.9, \(\beta\)2 = 0.999, \(\epsilon\) = 1e−6. Additionally, the GELU23 activation function was used, and a learning rate of 2e−5 was applied. For pre-training, the base scale model was trained for 7,000,000 steps, and the tiny model was trained for 27,000,000 steps, with a batch size of 2. For fine-tuning, the base model and tiny model were trained for 21,400 steps and 64,000 steps, respectively, with a batch size of 32. The fine-tuning process employed LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation)24, with the following LoRA parameters: rank = 16, \(\alpha\) = 16, dropout = 0.1.

Evaluation

The evaluation of the HeartBERT model was conducted through both internal and external assessments. Given that our model operates within a highly specialized domain, applying benchmark datasets is challenging. Therefore, in this study, we propose methods for internal and external performance evaluation that can be applied to models in specialized domains.

Perplexity

The masking approach is the most widely used method for training BERT. In this approach, a portion of the tokens in a sentence are randomly masked, and the model is tasked with predicting the original tokens. Masking involves replacing a token with a “[Mask]” token, thus obscuring the identity of the original token. This method allows us to assess BERT’s training progress and its overall understanding of language. Typically, there are multiple possible answers when predicting masked tokens.

For example, consider the sentence:

“My favorite fruit is apple.”

Assume we apply masking to create the following:

“My favorite fruit is [Mask].”

Ideally, the correct answer for the [Mask] in this sentence might be apple. However, filling it with banana or strawberry would not be necessarily considered incorrect either. Therefore, evaluating the model’s performance based solely on accuracy or correctness of the original answer is difficult. Instead, perplexity is used to assess the model’s performance. Perplexity can be understood as a measure of the model’s confidence in its predictions. A lower perplexity indicates better performance, as demonstrated below:

For a sentence W consisting of n words (\(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\), \(w_{3}\), ..., \(w_{n}\)), the likelihood of the sentence can be expressed as follows:

Applying the chain rule yields:

When applied to BERT, the perplexity for the [mask] token is calculated as the exponential of the negative log likelihood loss (nll loss)25.

Named entity recognition

NER15 refers to the task of identifying named entity within sentence. Sentences with tagged entities enable easier extraction of information compared to those without tags, and can be utilized for summarization, information protection26, and other purposes. Our development of a cardiology-related NER dataset began with the collection of cardiology-specific terms. These terms were derived from two main sources.

The first source is a publicly available cardiology glossary, which contain key terms selected by experts for their high reliability and importance. The second source is a collected cardiology dataset, from which keywords were extracted. KeyBERT27 can employed for this keyword extraction process. The extracted keywords were tagged with entity names using the GPT-4 API28. With these extracted words and entity labels, we created an NER dataset in the format “word : entity name”. Below is an example of the data format used for NER training:

Inputs : [Since, HUVECs, released, superoxide, ...., VCAM-1, ......]

Labels : [O, B-medical procedure, O, O,...., B-drug name, ....... ]

A total of 693 entities were extracted, and we classified them into four categories: Disease Name, Body Part, Medical Procedure, and Drug Name. In each entity category, 80% of the entities were used for training, and 20% were used for testing. Documents containing test entities were designated as test data and excluded from training. The number of each entity is shown in Table 1. consequently, the model performs a classification task predicting nine entity tags: Ordinary, B-Disease Name, I-Disease Name, B-Body Part, I-Body Part, B-Medical Procedure, I-Medical Procedure, B-Drug Name, and I-Drug Name. In this context, “B-” indicates the beginning token of an entity name consisting of multiple words, and “I-” represents the subsequent tokens within the entity name.

Using the constructed NER dataset, we fine-tuned and evaluated a pre-trained model for the NER task. Evaluation metrics such as precision, recall, and f-measure were employed to assess the model’s performance.

Results

Perplexity

Performance evaluation for masking task was conducted without additional fine-tuning. We randomly sampled 50 sentences from the test data, applied random masking to parts of these sentences, and then measured the perplexity based on the model’s predictions. Lower perplexity indicates better performance, and Fig. 3 shows the perplexity for 50 sentences. Figure 3a represents the results for models of the base scale, while Fig. 3b shows results for the Tiny scale models. Since lower perplexity signifies better performance, a graph positioned higher suggests poorer performance.

From Fig. 3a, it can be observed that the base scale model, BERT-base, exhibited the highest perplexity, followed by BioBERT, although apart from the maximum value recorded, it showed a similar pattern to other models. In Fig. 3b, Tiny models generally displayed significantly higher perplexity, indicating the lowest performance.Tiny-BioBERT showed the lowest perplexity among the Tiny models, with performance comparable to the larger base-scale models. The four models we trained, Tiny-continual v1/v2 and Tiny-scratch v1/v2, demonstrated moderate performance.

Table 2 presents the average perplexity results across 50 sentences. Among the base-scale models, continual-v2 showed the best results. Additionally, base-continual-v1/v2 and base-scratch-v1/v2 also performed better than the BERT-base and BioBERT models, indicating that our models have a better understanding of cardiology-related texts. Despite being trained on significantly less data than BERT-base or BioBERT, our models showed better performance, suggesting they are also more efficient. The CarioBERT model, trained on Portuguese, demonstrated the lowest performance on the test set composed in English (Due to scaling issues, CardioBERTpt was not included in the Fig. 3a).

In the Tiny scale models, Tiny-BioBERT demonstrated the most impressive performance with a perplexity of 5.78, while Tiny-BERT showed the bad performance. The inferior performance of Tiny-continual v1/v2 and Tiny-scratch v1/v2 compared to Tiny-BioBERT is likely attributed to the absence of distillation. The performance differences between Tiny-BERT and our models were significantly more pronounced than those observed with the base-scale models. Generally, the smaller the model size, the less information it can contain, which suggests that specialization of the model could be advantageous. This outcome supports that notion.

Differences in results according to the training approach and data were also observed. In base scale models, performance varied more with the size of the data rather than the training method used. Models trained on dataset version-1 and version-2 showed similar performance regardless of the training approach. For the sufficiently large base scale models, the quantity and diversity of data primarily influenced performance. On the other hand, in the case of Tiny-scale models, the training method had a more significant impact, with the continual approach demonstrating better performance.

Named entity recognition

The performance of the NER task was evaluated based on classification accuracy for a total of eight entities, excluding the normal entity. Performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and f1-score were utilized. Table 2 displays the NER Accuracy of the models. Accuracy was simply calculated based on the congruence between the model’s predicted entity tags and the actual entity tags.

For Tiny scale models, scratch-ver1 exhibited the best performance achieving an accuracy of 0.751. This suggests that training with precisely targeted data can be efficient in solving downstream tasks when the model size is small. Since the evaluation data was predominantly in the PubMed format, scratch-ver2, which included Wikipedia data, showed a slight performance decrease compared to scratch-ver1. In the case of continual models, the inclusion of previously trained data in the model resulted in a performance decrease for Downstream tasks in such Tiny scale models.

For the base-scale models, continual-ver2 exhibited the highest performance. This result suggests that, when the model size is sufficiently large, training with a diverse data is effective. The continual-ver2 model benefitted from incorporating the larger ver2 dataset into the previously learned information (continual training), resulting in the highest performance among all models. When comparing based on the size of the model under the same conditions, base models generally outperformed their Tiny counterparts. Additionally, our models demonstrated superior performance compared to existing models such as BERT or BioBERT.

Table 3 presents the precision, recall, and f1-score of the Tiny scale models for eight tags, resulting in a total of 24 metrics per model. From the results in Table 3, the Tiny scratch-ver1 model exhibited the highest performance in a total of 10 categories, representing the majority among the models. This suggests that the Tiny scratch-ver1 model can be considered the best-performing model, consistent with the accuracy results mentioned earlier.

In contrast, the base-scale models showed a different pattern compared to the accuracy experiment results. Table 4 displays the precision, recall, and f1-score results of the base-scale models, where the base scratch-v2, continual-v1 model demonstrated the highest performance across 8 categories, establishing itself as the superior model. This result presents a slightly different trend from the accuracy results. CardioBERTpt generally showed higher performance than the base model and achieved similar performance to BioBERT. Although CardioBERTpt was trained specifically on cardiology, its primary training in Portuguese likely contributed to the relatively lower performance on English datasets.

In summary of the NER test results, starting from scratch appears to be advantageous for the downstream task performance. Furthermore, our HeartBERT models outperformed the general-domain bert-base/tiny-bert models, particularly demonstrating generally higher performance in cardiac-related text data compared to BioBERT trained on medical domain corpora including PubMed.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we departed from conventional approaches of medical language modeling and focused on training and evaluating language models specialized in specific departments. We discussed methods for collecting datasets to train a cardiology-specific language model, with the potential for these methods to be applied to other departments as well. Moreover, we compared the training methods by categorizing them into continual and scratch training. Our findings indicated that for smaller models, the scratch training approach can be more advantageous.

Additionally, we discussed evaluating language models for specialized domains, distinguishing between internal and external evaluation methods. Internally, we assessed the model’s prediction performance through the masking task, while externally, we evaluated performance using NER task. Both evaluations produced results consistent with our theoretical expectations.

However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, there may be a lack of diversity in the data collected, as most of it was obtained from PubMed, potentially limiting the dataset’s diversity. We continue to work on increasing the diversity and quantity of the data, expecting significant improvements over time. Secondly, a limitation lies in the use of only two metrics for performance evaluation. Relying on a limited set of metrics may not provide a comprehensive assessment of model performance, emphasizing the need for evaluation from multiple perspectives.

While there exist various benchmarks for language models, most are focused on general domains. Although benchmarks for the medical domain exist, they are not applicable to finely segmented models like HeartBERT. To address this, we proposed constructing benchmark data using large models like ChatGPT, though potential errors may occur when utilizing such models. These limitations could be mitigated by developing Mixture of Experts (MoE) models and continuously evolving the evaluation metrics for these models.

Leveraging the data collection and training processes used in this study, our future goal is to train models for all departments and integrate them into a Mixture of Expert (MoE)29 model. This integrated model can be evaluated using general medical benchmarks, allowing for comparisons with other models and broader applicability.

Data availability

The version-1 datasets are available at https://huggingface.co/datasets/InMedData/Cardio_v1 and the version-2 datasets are available at https://huggingface.co/datasets/InMedData/Cardio_v2

References

Federation, W. H. Confronting the world’s number one killer. https://world-heart-federation.org/wp-content/uploads/World-Heart-Report-2023.pdf (2023).

Division of Chronic Disease Prevention, B. o. C. D. P., Control, K. D. C. & Agency, P. Cardio-cerebrovascular disease mortality trends, 2011–2021. Public Health Weekly Rep.17, 295–350 (2023).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 456 (2017).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint. arXiv:1810.04805 (2018).

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., Sutskever, I. et al. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. OpenAI blog (2018).

Radford, A. et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 1, 9 (2019).

Brown, T. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1877–1901 (2020).

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29, 1930–1940 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. A survey of large language models in medicine: Progress, application, and challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.05112 (2023).

Rasmy, L., Xiang, Y., Xie, Z., Tao, C. & Zhi, D. Med-bert: pretrained contextualized embeddings on large-scale structured electronic health records for disease prediction. NPJ Digital Med. 4, 86 (2021).

Bommasani, R. et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07258 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Meditron-70b: Scaling medical pretraining for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.16079 (2023).

Wu, C., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y. & Xie, W. Pmc-llama: Further finetuning llama on medical papers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.14454 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Chatdoctor: a medical chat model fine-tuned on a large language model meta-ai (llama) using medical domain knowledge. Cureus 15, 25 (2023).

Lample, G., Ballesteros, M., Subramanian, S., Kawakami, K. & Dyer, C. Neural architectures for named entity recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.01360 (2016).

Schneider, E. T. R. et al. Cardiobertpt: Transformer-based models for cardiology language representation in portuguese. In 2023 IEEE 36th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS) 378–381. https://doi.org/10.1109/CBMS58004.2023.00247 (2023).

Naga Suneetha, A. R. V. & Mahalngam, T. Fine tuning bert based approach for cardiovascular disease diagnosis. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 11, 59–66 (2023).

aikenphysicians. Cardiology glossary Of terms (2024, accessed 20 Feb 2024). https://aikenphysicians.com/services/cardiology/cardiology-glossary-of-terms//.

of Health, N. I. Heart Health Glossary (2024, accessed 20 Feb 2024). https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/heart-health/heart-health-glossary//.

Institute, T. T. H. Cardiovascular Glossary (2024, accessed 20 Feb 2024). https://www.texasheart.org/heart-health/heart-information-center/topics/a-z//.

Jiao, X. et al. Tinybert: Distilling bert for natural language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.10351 (2019).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Hendrycks, D. & Gimpel, K. Gaussian error linear units (gelus). arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.08415 (2016).

Hu, E. J. et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09685 (2021).

Salazar, J., Liang, D., Nguyen, T. Q. & Kirchhoff, K. Masked language model scoring. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.14659 (2019).

Ahmed, T., Aziz, M. M. A. & Mohammed, N. De-identification of electronic health record using neural network. Sci. Rep. 10, 18600 (2020).

MaartenGr. Keybert. https://github.com/MaartenGr/KeyBERT/?tab=readme-ov-file (2020).

Achiam, J. et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 (2023).

Shazeer, N. et al. Outrageously large neural networks: The sparsely-gated mixture-of-experts layer. arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.06538 (2017).

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R &D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HR21C0198) and by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI23C0896)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G. designed the data collection process for the training dataset and wrote the code for training and evaluation. Additionally, H.G. analyzed the results and wrote the paper. J.S. designed and developed the method for constructing the benchmark. Additionally, J.S. carried out the model training. S.P. contributed to designing the process for building the training dataset and was responsible for the actual dataset construction. Additionally, S.P. trained the model. Y.K. supervised and managed the overall research process, providing medical expertise. T.J.J. supervised and managed the overall research process, providing guidance for paper writing. All authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gwon, H., Seo, J., Park, S. et al. Medical language model specialized in extracting cardiac knowledge. Sci Rep 14, 29059 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80165-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80165-z