Abstract

This research aimed to increase the natural frequencies of a non-rotating 2D tri-axial braided composite (2DTBC) fan blade. The investigation utilized a multidisciplinary approach, integrating Artificial Neural Network (ANN) modeling, analytical method, Finite Element (FE) analysis, optimization techniques, and experimental validation. The ANN captured the complex relationship between the braiding machine and structure parameters. The mechanical properties of the 2DTBC were determined through the micromechanical modeling, and the thin-shell analysis was applied to describe the blade’s displacement and strain characteristics. Micromechanical modeling examines material behavior at the microscopic level, and thin shell analysis focuses on modeling and analyzing thin, curved structures using simplified equations. The FE method facilitated the formulation of the equation of motion and the calculation of natural frequencies. A genetic algorithm, focused on a single-objective optimization, was employed to refine the braiding structure parameters and the number of composite layers, thereby enhancing the blade’s natural frequencies. The optimized 2DTBC blade was subsequently fabricated and validated through impact hammer modal testing, showing strong agreement with the predictions from the combined ANN-analytical-FEM-GA model. The optimization of the braiding parameters led to a significant increase in the blade’s natural frequencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fan blade in a turbofan engine is crucial for air compression. Located at the engine’s front, it draws in and splits air into a core stream for combustion and a bypass stream for extra thrust, enhancing fuel efficiency. Made from advanced materials like carbon fiber or titanium, the blade is designed for strength, lightness, and durability. Vibrations from various sources can cause stress and fatigue, risking structural failure. To combat this, engineers use advanced materials and design techniques, such as finite element analysis, to ensure the blade’s strength and reliability.

A high-fidelity multiscale methodology for assessing the residual performance of 2DTBC under high-velocity impact has been introduced1. In a study, braided composite materials were employed to reduce the weight of a two-stage gear transmission system. These materials were applied to the gear webs, after which their dynamic characteristics were analyzed2. The hydrodynamic characteristics of fishing net panels constructed from various materials, including braided knotless netting, were examined at low angles of attack using a self-designed experimental setup3. A study examined the dynamic behavior of a dual-rotor system focusing on the scenario where the aerodynamic excitation frequency of the fan blades approaches the characteristic frequency of the inter-shaft bearings4. The response characteristics of a system under varying parameters or fault conditions were analyzed using a dynamic model5. A study demonstrates that a single-camera system employing Digital Image Correlation (DIC)-assisted fringe projection profilometry (FPP) is capable of generating full-field 3D images of complex components, such as honeycomb structures and braided composite tubes, while also measuring their deformation6. A study developed stretchable interconnections for mesoscale electronic mechanisms or components by utilizing stretchable textiles made from metallic fibers arranged in braided structures7. In a study, the free vibration behavior of rotating beams made of functionally graded materials (FGM) was investigated with an exponential distribution model and conical geometry8. The free vibration response of four-step 1 × 1 3D braided composite curved panels and rotating 3D braided composite pre-twisted conical shells was analyzed using finite element methods, considering a new shear deformation theory for the displacement field. The equivalent material properties of the composite were computed through a volume-averaging approach9,10. A novel fatigue-testing device was developed to replicate the motion of braided polypropylene knee ligaments within a liquid environment, and the mechanical performances of braided ligaments were discussed11. Theoretical research on the free vibration behavior of a standard final-stage low-pressure steam turbine blade was conducted and presented12. A design of high durable automotive hydraulic braking hose made of braided composite was performed with the interference-free layout to prevent complicated anisotropic large deformation13. A multi-objective optimization approach was proposed to reduce the significant deformation resulting from the cyclic motion of the fabric-braided brake hose in the driver’s braking system14. Research demonstrated that axial yarns improve the mechanical properties of braided composite tubes and decrease their susceptibility to bending damage15. A study examined how variations in axial yarn quantity and placement in tri-axial braided composite tubes affect their deformation and damage during transverse low-velocity impact16. The temperature rise phenomenon and failure behavior of tri-axial braided carbon/epoxy composites under impact loading conditions were analyzed using a mesoscale finite element model17. A study investigated the vibration characteristics of different laminate composite fan blades designed for high-tip-speed applications18. A triangular shell element with ten nodes was created and employed for the vibration analysis of cambered and twisted fan blades, allowing for the determination of natural frequencies across different parameters19. An experimental study on the effects of varying rotating speeds and stagger angles on the rotating blade’s natural frequencies is studied20. A three-dimensional continuum vibration analysis was conducted for rotating laminated composite blades, using a model based on three-dimensional elasticity21. A study explored the impact of fiber angle on the natural frequencies of orthotropic composite pre-twisted blades, employing the differential quadrature method22. Analyses on a composite blade for NASA Glenn Research Center’s Exo-Skeletal Engine (ESE) included aerodynamic, displacement, stress, buckling, modal, and progressive damage assessments23. A study on the structural analysis and optimization of composite fan blades revealed that fiber orientation significantly impacts the deformation behavior of the optimized blade24. The behavior of non-uniform in-plane shearing, pure extension of the yarns, and a combination of in-plane shearing and yarn extension of such fabrics under axial tensile loading were studied25. A thorough investigation into the structural dynamic modeling of rotating blades utilizing three-dimensional finite element analysis was presented26. A comprehensive analysis of the natural frequencies of fiber reinforced plastic (FRP) cooling tower fan blades was conducted to ensure they do not match excitation forces, thus avoiding resonance and structural damage 27. A numerical study on the vibration stress of a rotating fan blade under aerodynamic load at critical speed found that resonance occurs at several critical speeds28. A comprehensive study on composite compressor blades covered design, manufacturing, and testing, detailing a multi-step process for selecting blade geometry and composite architecture, including numerical stress, deformation, vibration, and failure analyses29. A study explored advanced methods for constructing high-performance fan blades with enhanced design flexibility, analyzing how varying ply orientation patterns affect the reliability of composite fan blades30. An enhanced dynamic model was developed for a rotating pre-twisted fan blade with arbitrary cross-section, accounting for coupling effects between bending, torsion, stretching31. A new dynamic model was used to study the vibration behavior of a rotating composite laminated fan blade with a pre-twisted angle32. A study investigated the vibration specifications of a titanium wide-chord fan blade, identifying critical locations for high-cycle fatigue and conducting random-excitation tests33. A study explored the application of composite materials to improve performance and reduce noise in jet engines by focusing on how fiber orientation affects vibration behavior34. A study analyzed the impact of thickness ratio and fiber orientation on the frequencies and mode shapes of laminated composite twisted cantilever plates35. A study examined the free vibration specifications of rotating thin-walled composite box beams, considering the effects of bending, extension and twisting coupling36. A refined structural dynamics model was developed for both rotating and non-rotating composite rotor fan blades, incorporating thick walls or those supported by honeycomb or foam cores37. The study investigated vibration and dynamic response control of non-uniform composite rotating blades using a distributed piezoelectric actuator system to suppress beam dynamics38. A numerically efficient super element with a combination of polynomials and trigonometric shape functions for the dynamic analysis of rotating tapered beams was conducted39. A study focused on composite airfoil blades’ vibration analysis using the orthotropic thin shell bending theory 40. A new model to simulate the biaxial over braiding process for complex preforms was developed41. A study aimed to detail fabric courses within a layup plan using a kinematic draping algorithm and optimizing their placement through a genetic algorithm, considering manufacturability, structural performance, material efficiency, and practical concerns42. A study on 3D braided rotating cylindrical shells showed the impact of parameters such as braiding angle, volume fraction, aspect ratio, and rotational speeds on their natural frequencies10. A study on the free vibration analysis of rotating laminated composite plate-type blades examined the influence of various factors, including rotation speed, twist angle, setting angle, fiber orientation angle, and variable thickness, on the vibration behavior of the composite panels43. A new theoretical model for analyzing the free vibration specifications of rotating hub-blade assemblies made of graphene Nano-platelet reinforced nanocomposites was carried out44. An artificial neural network and geometrical model were used to predict the tensile behavior of multi-ply yarns45,46.

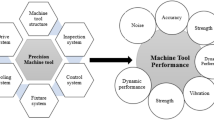

This research focuses on optimizing composite braiding parameters to increase the natural frequencies of fan blades, addressing a significant gap in current knowledge. Previous research has neither applied 2DTBC in blade structures nor attempted to optimize the vibration performance of 2DTBC blades. The present study comprehensively addresses these two objectives, constituting a primary contribution and a significant innovation of this research. It employs 2DTBC and a single-objective genetic algorithm to enhance blade natural frequencies, crucial for preventing resonance and ensuring structural integrity. 2DTBC offers unique mechanical properties compared to traditional composites, making them promising for improving fan blade performance in the aerospace, automotive, and energy sectors. The study uses an ANN to correlate braiding machine and structure parameters, focusing on the diamond tri-axial braid. Independent braiding machine parameters include carrier speed, take-off speed, blade chord length, and yarn count while braiding structure parameters involve braiding angle, braiding space, and the number of composite layers. Response surface method (RSM) and ANN analysis are employed to understand these relationships. Mechanical properties are determined through tensile testing and micromechanical methods, with structural behavior analyzed using Hamilton’s principle and finite element methods to calculate natural frequencies. Validation involves manufacturing composite blades based on optimized parameters and testing natural frequencies using impact hammer modal testing.

Modeling process

An integrated modeling approach incorporating ANN analysis, analytical methodologies, FE analysis, and experimental techniques was employed. The ANN relates braiding machine and structure parameters. Mandrels for the braiding process were fabricated using 3D printing. Micromechanics theory derived the mechanical properties of the 2DTBC. The FE method obtained the equation of motion for the 2DTBC blade, and a genetic algorithm optimized its natural frequencies. Impact hammer modal testing determined the natural frequencies of the 2DTBC blade. The research activities are illustrated schematically in Fig. 1.

Artificial neural network modeling

The ANN was utilized to derive braiding structure parameters from independent braiding machine parameters. Initially, Pearson’s correlation heatmap matrix was used to assess the relationships among input parameters, revealing low correlations as shown in Fig. 2a. Subsequently, analysis of output parameter correlations necessitated the use of two separate ANN models. Figure 2b demonstrates the application of a fivefold cross-validation method to validate model generalizability. To establish the connection between braiding machine and structure parameters, a feed-forward back-propagation network was implemented in MATLAB, Fig. 2c. Two separate networks were employed, each with a single output, optimizing predictive performance. The network architecture used tansigmoid transfer functions for hidden layers and pure linear for output layers. The number of nodes in the hidden layer was optimized through grid search (5 to 10 nodes). Key parameters like learning rate (0.1), momentum (0.9), and epochs (1000) were set using the Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) learning algorithm. It can be deduced from references47,48 that the (LM) algorithm enhances the training of feed-forward back-propagation networks by integrating features of both gradient descent and Newton methods. This approach enables more efficient optimization with rapid convergence and high accuracy, particularly in complex and challenging problems. Due to its dynamic adjustment between these two methods, the LM algorithm reduces the risk of becoming trapped in local optima, making it especially well-suited for small to medium-sized networks. Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis, Fig. 2d highlighted the influence of individual input parameters. The perimeter significantly impacted braiding space (43.4% variance), while take-off speed had the greatest effect on braiding angle (38.6%).

As illustrated in Fig. 2d, the chord length has the most significant effect (43.4%) on the braiding space. The analysis shows that modifying the airfoil’s chord length, which in turn affects its perimeter, influences the parameters of the braiding structure. With the yarn count, carrier speed, take-off speed, and number of carriers held constant, chord length changes lead to braiding space variations. Specifically, increasing chord length expands the braiding space, thereby reducing the yarn density. This effect has been identified as a key parameter in neural network training, as it plays a critical role in predicting the structural characteristics of the braided component. Tables 1 and 2 present a comprehensive summary of the weight and bias parameters associated with the developed neural network, specifically focusing on the variables associated with braiding space and braiding angle, respectively. It is imperative to note that these values are representative of the network configuration for Fold 1, where consistent weight and bias values have been maintained to ensure the production of a stable output.

In neural networks, weights and biases are the model’s training parameters. Weights are situated along the connections between neurons, indicating the significance of each input by scaling it through multiplication. Bias, on the other hand, is an additional parameter added to each neuron’s output. It enables the model to fine-tune outputs independently of the inputs and thereby enhances model flexibility. During the training process, both weights and biases are iteratively adjusted to minimize model error, ultimately leading to improved performance and results. As illustrated in Fig. 2c, the z parameter represents the weight matrix connecting the input layer to the hidden layer. In contrast, the w parameter represents the weight matrix between the hidden layer and the output layer47,48.

Multi-scale analytical modeling

The segment describes a study on a 2DTBC, focusing on its mechanical properties at different scales. It begins with an analysis at the microscale using a unit cell from the composite yarn, then moves to the mesoscale with a unit cell representing the entire 2DTBC. The composite structure consists of three types of yarns: counterclockwise, clockwise, and axial, braided to form layers of 0°/± θ° material. Figure 3 illustrates the multi-scale modeling approach for the 2DTBC. At the microscale, the fiber cross-section is circular, whereas at the mesoscale, the cross-section of the fiber tows is elliptical.

Equivalent mechanical properties of microscale RUC model

Within the microscale RUC framework, fibers are organized in a hexagonal configuration, facilitating the attainment of a substantial fiber volume fraction. The adjustment of the fiber volume fraction in this model is configured to \({\text{v}}_{\text{f}} = 0.8\). The Chamis’ equations are determined the equivalent mechanical properties of the microscale RUC model as follows49.

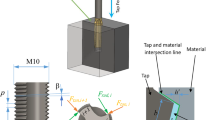

Equivalent mechanical properties of mesoscale RUC model

Figure 4 depicts the mesoscale RUC model of 2DTBC. A global coordinate system is defined for the model, with the x-axis aligned along the axial yarn, the y-axis perpendicular to the axial yarn, and the z-axis oriented along the thickness of the model. The length and width of the cell (L and W) are equal to the projection of the braiding space along the axial yarn direction and its perpendicular direction, respectively. The braiding space itself (P) refers to the straight distance between two adjacent intersection points of the bias yarns, and θ denotes the braiding angle. The axial yarn denoted by the index "a", the bias yarn by the index "b" and the matrix by the index "m", with the assumption that the axial fiber tows follow a straight path, while the bias fiber tows exhibit an rippling effect. It is further assumed that the cross-sectional area of the fiber tows remains constant along its trajectory50. If this assumption is relaxed, the fiber volume fraction in the mesoscale RUC model will vary, leading to changes in the mechanical properties of the 2DTBC. Subsequently, the fiber volume fraction within the tow and unit cell and the tows’ volume are determined50.

Figure 5 presents a comprehensive rippling profile through unit cell thickness. The axial fiber tow is depicted as ellipses, while one of the two bias fiber tows is represented as black rippling curves. The dimensions of the fiber tows, namely the thickness and width, are denoted as \({\text{h}}_{\text{y}}\) and \({\text{w}}_{\text{y}}\), respectively. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the fiber’s local coordinate undergoes continuous changes along the y-coordinate. It is assumed that the axial and bias tows are tangent to each other.

The fiber tow rippling is characterized by employing the central line (represented by a dashed line in Fig. 5) and is expressed through a designated function.

Subsequently, the rippling angle α(y) through thickness can be articulated as follows

\(\upalpha \left( {\text{y}} \right)\) represents the projected angle of the bias fiber tows rather than their actual rippling angle. The rippling \(\upbeta \left( {\text{y}} \right)\) of the bias fiber tows is calculated by multiplying \(\upalpha \left( {\text{y}} \right)\) by the sine of the rippling angle.

The equivalent stiffness matrix for rippling tows is derived by averaging the transformed local stiffness matrix across the width of the unit cell50,

Here, C denotes the stiffness matrix, \({\upsigma }_{\text{b}}\) and \({\upvarepsilon }_{\text{b}}\) represent the stress and strain of the bias fiber tows, respectively, and R is the transformation matrix.

Where

Here, \(\upbeta\) denotes the rippling angle, and \(\uptheta\) represents the braiding angle. The method is applied to both positive and negative bias fiber tows to determine the equivalent stiffness matrix \({\text{C}}^{\text{eq}}\). The exact formula for the length of the bias fiber tow is derived through the integration process.

This method is applied to axial yarns, bias yarns, and the pure matrix. The global equivalent stiffness matrix of the unit cell is then obtained using the volume averaging method50,

The effective engineering constants for the unit cell are derived from the global stiffness matrix \({\text{C}}^{\text{global}}\). Equation (9) is applied for the evaluation of the mechanical properties of the mesoscale RUC model for 2DTBC. This equation is extrapolated from the discoveries made by50 and has been empirically validated. There is no necessity for revalidation within the context of this manuscript.

Governing equations of composite shell

The blade is a closed curved surface. For this reason, the shell theory is used to express the equations of motion. Illustrated in Fig. 6 is a rectangular surface characterized by uniform thickness, featuring a laminated curved shell sample. The coordinate system is defined as \(\left({\upxi }_{1}, {\upxi }_{2},\upzeta \right)\), where \({\upxi }_{1}\) and \({\upxi }_{2}\) represent the curvatures of the middle surface \(\left(\upzeta =0\right)\). Before the deformation of the shell, a point located on the middle surface is denoted by "r", while a point outside the middle surface is denoted by "\({\text{R}}_{0}\)", as depicted in Fig. 6b.

Geometry of a laminated composite shell; (a) shell geometry; (b) position vectors of points on the midsurface and above the midsurface51.

Herein, \({\text{R}}_{1}\) and \({\text{R}}_{2}\) represent the principal radii of curvature corresponding to the middle surface, as illustrated in Fig. 6a. The subsequent outcome can be acquired for the mono-curvature shell characterized by infinite radius along one direction.

Also, for thin and shallow shells, the following expression can be written.

Using the displacement field, the governing equations for the First-order Shear Deformation Theory (FSDT) for orthotropic layered shells are derived via Hamilton’s principle51

The parameters \(\left({\text{N}}_{\text{xx}}, {\text{N}}_{\text{yy}}, {\text{N}}_{\text{xy}}\right)\) represent the in-plane force resultants, \(\left({\text{M}}_{\text{xx}}, {\text{M}}_{\text{yy}}, {\text{M}}_{\text{xy}}\right)\) describe the moment resultants, \(\left({\text{Q}}_{\text{x}}, {\text{Q}}_{\text{y}}\right)\) are the transverse force resultants, \(\left({\text{I}}_{0}, {\text{I}}_{1}, {\text{I}}_{2}\right)\) signify the mass moments of inertia, and \(\left( {{\text{u}}_{0} ,{\text{v}}_{0} ,{\text{w}}_{0} ,\varnothing_{{\text{x}}} ,\varnothing_{{\text{y}}} } \right)\) denote the generalized displacements. All stress resultants are expressed per unit length, for instance, \({\text{N}}_{\text{i}}\) and \({\text{Q}}_{\text{i}}\) in N/m, and \({\text{M}}_{\text{i}}\) in N.m/m. Where, (note that \(\zeta =z\))

Where \(\rho\) is the density of the laminated composite. The stress resultants per unit length may be delineated as follows51

Where h is the shell thickness. The shear forces \({\text{Q}}_{\text{i}}\) are defined by51,

Where \({\text{K}}_{\text{s}}\) is the shear correction factor.

Finite element modeling

The generalized displacements for the FSDT consist of \(\left( {{\text{u}}_{0} ,{\text{v}}_{0} ,{\text{w}}_{0} ,\varnothing_{{\text{x}}} ,\varnothing_{{\text{y}}} } \right)\). The weak forms of the five equations in Eqs. (12)-(16) are derived. Consequently, these weak forms are approximated using Lagrange interpolation functions. For the sake of simplicity, the same interpolation is applied to all variables.

Where \({\uppsi }_{\text{j}}^{\text{e}}\) are Lagrange interpolation functions. Coordinate transformations are used in the FE simulation for simplifying mathematical formulations and handling complex geometries. The interpolation of \(\left({\text{u}}_{0}, {\text{v}}_{0}, {\text{w}}_{0}\right)\), and \(\left({{\varnothing }}_{\text{x}},{{\varnothing }}_{\text{y}}\right)\) is executed using a nine-node quadratic Lagrange rectangular element that has transformed into the local coordinate system \(\left\{\left(\upxi ,\upeta \right):-1\le\upxi \le 1,-1\le\upeta \le 1\right\}\), as illustrated Fig. 7.

Also, the transformed interpolation functions are given

By substituting Eqs. (20)-(24) instead of the variables \(\left( {{\text{u}}_{0} ,{\text{v}}_{0} ,{\text{w}}_{0} ,\varnothing_{{\text{x}}} ,\varnothing_{{\text{y}}} } \right)\) within the weak form equations, the finite element model of the blade is derived.

The finite element model represents a set of algebraic equations involving nodal values corresponding to generalized displacements. The Gauss quadrature technique is employed for the evaluation of them. The element matrices are assembled to integrate the local contributions of individual elements into a unified global matrix. Hence, the equation of motion for the clamped blade structure is expressed in the subsequent matrix form.

Where Δ contains global displacement variables as follows

The assumption of clamped-free boundary conditions is aligned with practical operating scenarios and previous studies in this field5,12,18,21,22. It is well-established that the natural frequency of a clamped-free blade is higher than that of blades with alternative boundary conditions, such as free or partially constrained ends. So, the clamped-free boundary conditions assumption is retained throughout the analysis to ensure practical relevance and comparability with existing research.

Optimization step

The single-objective genetic algorithm is used for optimization. It is an optimization technique inspired by the principles of natural selection and genetics. The single-objective genetic algorithm employs a population of potential solution represented as individuals, each characterized by a set of decision variables. Through successive generations, individuals evolve by undergoing processes such as selection, crossover, and mutation52,53. Within the current investigation, the optimization parameters encompass braiding angle, braiding space, yarn count, and number of composite layers. Throughout the optimization process, the hyper parameters were configured according to the values specified in Table 3.

Where Pareto fraction determines the portion of solutions in each generation retained on the Pareto frontier, promoting a wider range of optimal solutions. Maximum generation sets the maximum allowable generations, balancing computational efficiency with the quality of the final solution. Population size specifies the number of solutions per generation, critical for maintaining search space diversity and exploration breadth. Population type defines the data type for population members; for continuous variables, double-precision vectors are often preferred. Creation function generates the initial population with solutions that adhere to problem constraints. Selection function determines selection methods for reproduction, often introducing competition through techniques like tournaments. Selection size specifies the number of members chosen at each selection stage, controlling competition intensity. Mutation function maintains genetic diversity by introducing small random changes, helping prevent premature convergence. Mutation fraction indicates the proportion of the population undergoing mutation in each generation, balancing solution diversity and stability. Crossover function combines parent solutions to produce offspring, facilitating feature inheritance from parents to children. Crossover fraction defines the percentage of the population generated through crossover, blending top solutions for optimized combinations52,53. The objective function used for optimization is as follows:

Subjected to

Where \(\text{x}\) is a vector to store optimization parameters, \(\upomega , {\text{V}}_{\text{t}}, {\text{V}}_{\text{c}},\text{ C},\text{D},\text{ N}\) are the natural frequency, take-off speed, carrier speed, chord length, yarn count, and number of composite layers.

Due to the range of variation in number of braiding layers from 3 to 6, the second term within the bracket \(( {\underbrace {{{\text{V}}_{{\text{t}}} ,{\text{V}}_{{\text{c}}} ,{\text{C}},{\text{D}}}}_{{3{\text{ to }}6{\text{ times}}}}} )\) will be multiplied 3 to 6 times during the optimization. Thus the overall length of the chromosome will be 25 genes. It should be mentioned that the optimization was undertaken on MATLAB software.

Experimental work

The experimental phase process is shown in Fig. 8. First, the bobbins filled with glass yarn were placed in the braiding machine. The response surface method (RSM) was used to systematically design the experiments. The experimental parameters with their variations listed in Table 4. Fifteen distinct cases were designed, as detailed in Table 5. Three PLA blades with equal span lengths and chord lengths of 3, 4.5, and 6 cm, featuring the NACA 0018 airfoil cross-section, were fabricated using a 3D printer. These blades were installed as mandrels in the braiding machine to create the braiding structure. The experiment aimed to establish a correlation between the braiding machine and structure parameters. Image processing and vertical photography of the braided structure were used to measure the braiding angle and space as shown in Fig. 8. The diameter of the glass fiber was measured using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, XL30-SFEG, and FEI Philips, Japan). The mechanical properties of the glass yarn were determined by employing the Instron 5566 device, subjected to a constant rate of elongation at 200 mm/min, following the standards outlined in ASTM D 3822–01. Subsequently, the acquired variables were integrated into a hybrid model as input for optimization. Following optimization, a 2DTBC blade sample was fabricated through the vacuum infusion process based on the optimized braiding parameters. The epoxy resin dog bone specimen was made according to ASTM D638-14 standards, and its mechanical properties were evaluated using a SANTAM-STM-150 tensile machine. Cantilever support conditions for the 2DTBC blade were established, and impact hammer modal testing was conducted to determine the natural frequencies. The hammer modal testing is not applied to rotating blades, as high-speed rotation prevents the use of a hammer for impact testing. During rotation, excitation can be introduced by a controlled imbalance or by a shaker that applies a periodic force to the blade at various frequencies. In some setups, piezoelectric or electromagnetic actuators provide a controlled excitation that can be synchronized with rotation speed. In the finite element section, only a rotational stiffness matrix can be incorporated into the existing stiffness matrix. Therefore, this study’s approach could be applied to rotating blades, assuming modal testing can be adapted for rotating conditions.

Results and discussions

Experimental results

During this investigation, a series of diverse experimental examinations were executed, and the ensuing outcomes are delineated within this segment. The stress–strain curves resulting from the tensile test conducted on glass yarn, and epoxy resin are illustrated in Fig. 9. The mechanical properties of the glass yarn and epoxy resin are cataloged in Table 6. Six samples of glass yarn, with counts of 400, 800, and 1200 tex and a length of 25 cm, were subjected to tensile testing, and the average stress–strain curves from these tests were used as the final stress–strain curve for glass yarn. Additionally, six epoxy resin dog-bone samples, measuring 246 mm × 29 mm × 3.2 mm, were fabricated and tested under tension, with their average stress–strain curves serving as the final stress–strain curve for the epoxy resin. The SEM analysis revealed a glass fiber diameter measuring 11 µm.

Employing image processing technique on the braided structure facilitated the determination of the braiding angle and space across 15 distinct scenarios of Table 5, elucidated in Table 7.

Performance of ANN models

Figure 10(a)-(b) demonstrate the performance of ANN-based models in correlating braiding machine and structure parameters during the training and testing phases, respectively. The models show an excellent correlation between predicted and actual values, achieving a 100% correlation coefficient. Additionally, Fig. 10(c)-(d) illustrate the goodness of fit for braiding space during training and testing phases, while Fig. 10(e)-(f) do the same for braiding angles. The consistently high fitness across these figures confirms the model’s effectiveness in mapping braiding machine parameters to braid properties, evidenced by a high coefficient of determination (R2). This high performance is consistently observed across other dataset folds as well.

Optimization results

Figure 11 illustrates the optimization procedure employed to address the problem at hand. The convergence of the optimization process is evident, as it reached a stable state within 30 generations. Moreover, the data space exhibits a significant level of diversity, encompassing all conceivable solutions. Consequently, the ultimate solution obtained corresponds to the global minimum, signifying the highest attainable bending natural frequency achievable through the fabrication of a 2DTBC fan blade. Figure 11 delineates the best, worst, and mean scores. The apex of the vertical bars represents the worst score, while the nadir signifies the best score. The mean score initiates near the worst score and incrementally converges towards the best score, exhibiting relative constancy within generations 25 to 30. Multiple runs were performed with varying initial inputs to address potential concerns about convergence challenges, which consistently led to the same results. This consistency indicates that convergence was achieved outside local minima, ensuring the robustness of the solution and the reliability of the optimization process.

Optimization through the single-objective genetic algorithm identified optimal parameters for the braiding structure of a 2DTBC blade. It was found that using a tri-layered composite configuration increases the blade’s natural frequencies. Each layer possesses distinct characteristics, delineated in Table 8. The first layer, with a braiding angle of 77.4 degrees, strengthens the blade transversely and improves twisting frequency. The next two layers, with a braiding angle of 43 degrees, reinforce both longitudinally and transversely. The addition of axial yarn in the tri-axial braid, especially in the second and third layers, enhances longitudinal strength due to a higher yarn count of 1200 tex, increasing the fiber volume fraction and overall composite strength. Tri-axial braids are superior to biaxial braids54, offering better fiber volume fraction adjustments and more efficient optimization of braiding angle and space, outperforming alloys and other textile configurations.

The impact hammer modal testing of the composite blade was conducted, and the resultant data are presented in the graphical representation depicted in Fig. 12.

In logarithmic scale, the vertical axis signifies magnitude, while the horizontal axis denotes frequency. Peaks on the graph indicate the presence of natural frequencies, with each peak corresponding to a specific natural frequency. For instance, the initial peak corresponds to the first natural frequency. Table 9 provides a tabulation of the first six natural frequencies for the 2DTBC blade. To evaluate the efficacy of the finite element method, the optimized 2DTBC blade was analyzed. Table 9 presents a comparative analysis of the natural frequencies of the optimized 2DTBC blade obtained through both finite element and modal testing methods, revealing a noteworthy concurrence between the results and affirming the accuracy of both methodologies.

One of the merits associated with undertaking this research stemmed from the meticulous approach taken to emulate the blade structure with utmost fidelity to real-world conditions. Consequently, the first-order shear deformation theory was employed to articulate the displacement vector, while the shell model was utilized to delineate the motion equations dictating the behavior of the blade. Furthermore, noteworthy advantages of this endeavor encompassed the adoption of the 2DTBC structure over alternative composite configurations for the blade, demonstrating practical feasibility in implementing this particular structural framework.

Performance of FE model

A mesh study was conducted to investigate the performance of the FE model, in which the nine-node quadratic Lagrange element has been implemented. This study determined that a mesh configuration of 12,540 elements and 85,822 nodes is sufficient to achieve converged results. The convergence curve for the first natural frequency of the optimized 2DTBC blade is presented in Fig. 13, with corresponding data provided in Fig. 14.

Conclusion

This paper aims to enhance the natural frequencies of the 2DTBC fan blade by optimizing the braiding structure. The braiding angle, braiding space, yarn count, chord length and number of composite layers are key parameters in increasing the natural frequencies. The single-objective genetic algorithm optimization method is employed to optimize these parameters. A 2DTBC blade sample is fabricated based on the optimized parameters, and its natural frequencies are measured using the impact hammer modal test. The objective is to surpass the natural frequencies of other composite or alloy blades, thus mitigating the occurrence of resonance. The findings can be summarized as follows:

-

The single-objective genetic algorithm demonstrates high efficiency as an optimizer when integrated into the developed multi-approach model for the 2DTBC fan blade.

-

Maximizing the bending natural frequency of the 2DTBC fan blade increases the torsional natural frequency, as these two frequencies are correlated.

-

Braiding technology proves advantageous over other manufacturing methods in terms of fabricating fan blades, as it allows for easy structural parameters (i.e. braiding angle, braiding space) manipulation to achieve higher natural frequencies.

-

The integration of artificial neural network, analytical models, and numerical simulation in a multi-approach model offers a robust engineering tool for accurately predicting the natural frequency of the 2DTBC fan blade, with an error rate of maximum 1.8%.

The potential areas for future research could include exploring the application of 2DTBC in more complex geometries, such as twisted taper blades and conical shapes. In such geometries, both carrier speed and take-off speed must be variable and precisely controlled, adding complexity to the fabrication of 2DTBC structures. Another suggestion could be to investigate the effect of using hybrid materials in yarns on the dynamic performance of these geometries.

Data availability

The datasets generated and used in this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhu, X. et al. A high fidelity multiscale approach for compression-after-impact behavior of 2D triaxially braided composites. Thin-Walled Struct. 199, 111793 (2024).

Zhang, W. Structural design and dynamic characteristics analysis of braided composite two-stage gear transmission system. Sci. Rep. 14, 5584 (2024).

Tang, H. et al. Variations in hydrodynamic characteristics of netting panels with various twine materials, knot types, and weave patterns at small attack angles. Sci. Rep. 9, 1923 (2019).

Zuo, G., Hou, L., Lin, R., Ren, S. & Chen, Y. Combination resonance and primary resonance characteristics of a dual-rotor system under the condition of the synchronous impact of the inter-shaft bearing. Sci. Rep. 13, 1153 (2023).

Yang, J., Xie, J., Wang, T., Yang, F. & Chen, J. The vibration response mechanism of a blade disk rotor system under the coupling effects of cracks and aerodynamic forces. Sci. Rep. 12, 1520 (2022).

Wu, Z. et al. Three-dimensional shape and deformation measurement on complex structure parts. Sci. Rep. 12, 7760 (2022).

Yun, M. J., Sim, Y. H., Lee, D. Y. & Cha, S. I. Highly stretchable large area woven, knitted and robust braided textile based interconnection for stretchable electronics. Sci. Rep. 11, 4038 (2021).

Taima, M. S., Shehab, M. B., El-Sayed, T. A. & Friswell, M. I. Comparative study on free vibration analysis of rotating bi-directional functionally graded beams using multiple beam theories with uncertainty considerations. Sci. Rep. 13, 17917 (2023).

Maji, P. & Singh, B. N. Shear deformation theory for free vibration responses of 3D braided pre-twisted conical shells under rotation. Int. J. Comput. Methods Eng. Sci. Mech. 23, 99–118 (2022).

Maji, P. & Singh, B. N. Free vibration responses of 3D braided rotating cylindrical shells based on third-order shear deformation. Compos. Struct. 260, 113255 (2021).

Marzougui, S., Kilani, L., Ben Abdessalem, S. & Sakli, F. Dynamic fatigue of braided textile ligaments. Arab J. Sci. Eng. 39, 2205–2214 (2014).

Shetkar, K. A. D. R. & Srinivas, J. Analytical modeling and vibration analysis of the last-stage LP steam turbine blade made of functionally graded material. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 46, 7363–7377 (2021).

Cho, J. & Kim, Y. Analysis of large deformation and fatigue life of fabric braided composite hose subjected to cyclic loading. Steel Compos. Struct. Int. J. 21, 949–962 (2016).

Kim, Y. H. & Cho, J. R. Multi-objective durability and layout design of fabric braided braking hose in cyclic motion. Steel Compos. Struct. Int. J. 25, 403–413 (2017).

Liu, Y., Chen, X., Wu, Z., Shi, L. & Li, J. Effect of axial yarn distribution on the progressive damage behavior of braided composite tube subjected to three-point bending. Thin-Walled Struct. 181, 110123 (2022).

Pan, Z., Qiao, F., Yu, J., Ouyang, W. & Wu, Z. Distribution of axial yarns on the localized deformation and damage mechanism of triaxial braided composite tubes. Thin-Walled Struct. 177, 109389 (2022).

Liu, P., Cai, Y., Zhao, Z. & Zhang, C. High-fidelity prediction and temperature-rise mechanism for low-velocity impact of triaxially braided composites. Thin-Walled Struct. 195, 111360 (2024).

Chamis, C. Vibration characteristics of composite pan blades and comparison with measured data. J. Aircr. 14, 644–647 (1977).

Khader, N. & Abu-Farsakh, G. A triangular shell element for vibration analysis of cambered and twisted fan blades. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 6, 287–301 (1990).

Fan, Y., Ju, M. & Tsuei, Y. Experimental study on vibration of a rotating blade. (1994).

McGee, O. & Chu, H. Three-dimensional vibration analysis of rotating laminated composite blades. (1994).

Kuang, J.-H. & Hsu, M.-H. The effect of fiber angle on the natural frequencies of orthotropic composite pre-twisted blades. Compos. Struct. 58, 457–468 (2002).

Abumeri, G. H., Kuguoglu, L. H. & Chamis, C. C. Composite fan blade design for advanced engine concepts. (2004).

Coroneos, R. M. & Gorla, R. S. R. Structural analysis and optimization of a composite fan blade for future aircraft engine. Int. J. Turbo Jet-Engines 29, 131–164 (2012).

Li, J., Hamila, N., L’Hostis, G. & Wang, P. Shear deformation characteristics under tensile stress during forming of tubular braided fabrics. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 167, 107458 (2023).

Kee, Y.-J. & Shin, S.-J. Structural dynamic modeling for rotating blades using three dimensional finite elements. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 29, 1607–1618 (2015).

Khandare, R., Londhe, B. & Ganore, D. Vibration analysis of fiber reinforced plastic fan blade. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2, 2395–2400 (2015).

Kou, H.-J., Lin, J.-S. & Zhang, J.-H. Numerical study on vibration stress of rotating fan blade under aerodynamic load at critical speed. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G: J. Aerosp. Eng. 230, 1044–1058 (2016).

Wollmann, T. et al. Design and testing of composite compressor blades with focus on the vibration behaviour. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 92, 183–189 (2017).

Xiao, J., Chen, Y., Zhu, Q., Lee, J. & Ma, T. In Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air. V07AT30A005 (American Society of Mechanical Engineers).

Oh, Y. & Yoo, H. H. Vibration analysis of a rotating pre-twisted blade considering the coupling effects of stretching, bending, and torsion. J. Sound Vib. 431, 20–39 (2018).

Chen, J. & Li, Q.-S. Vibration characteristics of a rotating pre-twisted composite laminated blade. Compos. Struct. 208, 78–90 (2019).

Wang, Z., Chen, Y., Ouyang, H. & Wang, A. Investigation of vibration characteristics of titanium wide-chord fan blade. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 8, 529–540 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. Understanding stiffness degradation of composite helical springs with multi-braided layers under impact. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 185, 108327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2024.108327 (2024).

Qatu, M. S. & Leissa, A. W. Vibration studies for laminated composite twisted cantilever plates. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 33, 927–940 (1991).

Chandra, R. & Chopra, I. Experimental-theoretical investigation of the vibration characteristics of rotating composite box beams. J. Aircr. 29, 657–664 (1992).

Jung, S. N., Nagaraj, V. & Chopra, I. Refined structural dynamics model for composite rotor blades. AIAA J. 39, 339–348 (2001).

Na, S., Librescu, L., Rim, S.-N. & Yoon, G.-C. Vibration and dynamic response control of nonuniform composite rotating blades. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 2006 (2006).

Gunda, J. B., Singh, A. P., Chhabra, P. S. & Ganguli, R. Free vibration analysis of rotating tapered blades using Fourier-p superelement. Struct. Eng. Mech. 27, 243–258 (2007).

Sinha, S. K. & Zylka, R. P. Vibration analysis of composite airfoil blade using orthotropic thin shell bending theory. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 121, 90–105 (2017).

Vu, A., Grouve, W. & Akkerman, R. Modeling of yarn interactions for non-axisymmetric biaxial overbraiding simulations. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 167, 107421 (2023).

Krogh, C., Hermansen, S. M., Lund, E., Kepler, J. & Jakobsen, J. A matter of course: Generating optimal manufacturing instructions from a structural layup plan of a wind turbine blade. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 172, 107599 (2023).

Kumari, E. Free vibration analysis of rotating laminated composite plate type blades with variable thickness. Mater. Today: Proc. 43, 1762–1773 (2021).

Zhao, T. Y., Jiang, Z. Y., Zhao, Z., Xie, L. Y. & Yuan, H. Q. Modeling and free vibration analysis of rotating hub-blade assemblies reinforced with graphene nanoplatelets. J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 56, 563–573 (2021).

Razbin, M., Salehian, M. & Gharehaghaji, A. A. A viscoelastic-plastic model for the core of various close-packings of multifilament polyamide-6 yarns. Sci. Rep. 14, 23800 (2024).

Razbin, M. et al. Artificial neural network-assisted theoretical model to predict the viscoelastic–plastic tensile behavior of polyamide-6 multi-ply yarns. Neural Comput. Appl. 36, 18107–18123 (2024).

Mousavi, S. M., Azizi, A. S., Razbin, M., Darzi, A. A. R. & Li, M. Optimized design of helical-finned double pipe heat exchangers via numerical simulation and artificial intelligence. Appl. Therm. Eng. 124605 (2024).

Azizi, A. S., Razbin, M., Mousavi, S. M., Li, M. & Darzi, A. A. R. Enhancing thermal efficiency in twisted tri-lobe double pipe heat exchangers via integrated CFD and AI approaches. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 206, 109331 (2024).

Chamis, C. C. in Ann. Conf. of the Society of the Plastics Industry (SPI) Reinforced Plastics/Composites Inst.

Zhang, C., Binienda, W. K. & Kohlman, L. W. Analytical model and numerical analysis of the elastic behavior of triaxial braided composites. J. Aerosp. Eng. 27, 473–483 (2014).

Reddy, J. N. Mechanics of Laminated Composite Plates and Shells: Theory and Analysis 2nd edn. (CRC Press, 2003).

Shahmoradi Ghaheh, F., Razbin, M., Tehrani, M., Zolfipour Aghdam Vayghan, L. & Sadrjahani, M. Modeling and optimization of dyeing process of polyamide 6 and woolen fabrics with plum-tree leaves using artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 14, 15067 (2024).

Darzi, A. A. R., Mousavi, S. M., Razbin, M. & Li, M. Utilizing neural networks and genetic algorithms in AI-assisted CFD for optimizing PCM-based thermal energy storage units with extended surfaces. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 54, 102795 (2024).

Boris, D., Xavier, L. & Damien, S. The tensile behaviour of biaxial and triaxial braided fabrics. J. Ind. Text. 47, 2184–2204 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to the Amirkabir University of Technology for their steadfast support throughout this research endeavor. Their provision of essential resources and tools has been instrumental in the successful execution of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mortaza Salehian conceptualized, investigated, and wrote the main manuscript text. Hamid Reza Ovesy conceptualized, supervised, and investigated the manuscript. Hadi Dabiryan prepared the braiding machine. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salehian, M., Ovesy, H.R. & Dabiryan, H. Free vibration optimization of 2D tri-axial braided composite fan blade with ANN-Anal-FEM-GA integrated model. Sci Rep 14, 28819 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80198-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80198-4