Abstract

Prior research on e-cigarettes’ health impacts is inconclusive due to confounding by previous tobacco smoking. Studies of e-cigarette use among people without an established smoking history are informative for this question. A cross-sectional survey was administered across six geopolitical world regions to adults aged 18+ without a history of established cigarette smoking or regular use of other nicotine/tobacco products. Two cohorts were defined based on e-cigarette use: “Vapers Cohort” (N = 491) who used e-cigarettes in the past 7 days and “Control Cohort” (N = 247) who never regularly used e-cigarettes. Frequency of respiratory symptoms (Respiratory Symptom Evaluation Score (RSES)) were compared between cohorts, adjusting for sociodemographics. Tobacco use history and patterns of e-cigarette use was also examined. Respiratory symptoms were rare among both the Vapers and Control Cohorts: 83.3% and 88.4%, respectively, reported “rarely” or “never” experiencing all five RSES items (p = 0.125). The Vapers (vs. Control) Cohort reported modestly more frequent respiratory symptoms (adjusted mean RSES 1.61 vs. 1.43, respectively, p < 0.001); however, this difference (0.18) did not reach the threshold of clinical relevance (0.57). The Vapers (vs. Control) Cohort more often reported former cigarette experimentation (30.8% vs. 12.1%) and former infrequent use of other nicotine/tobacco products (18.1% vs. 5.8%). The Vapers Cohort most often used disposable devices (63.7%) and multiple flavors (approximately 70–80% across primary device type). In this cohort of adults without a history of established combustible tobacco use, e-cigarette use was statistically linked to more frequent respiratory symptoms, though not in a clinically meaningful way. The cross-sectional design of this study cannot establish causality between e-cigarette use and respiratory symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (ECs) have become increasingly popular among people who smoke (PWS) as a potential harm reduction tool and smoking cessation aid1,2 due to their cost-effectiveness3 and the ability to mimic the smoking experience without combustion or smoke production4,5.

However, concerns have been raised about the health risks of ECs, with several papers reporting higher rates of respiratory conditions among people who use ECs than among nonusers6,7,8. However, since the majority of adults who use ECs currently or formerly smoke cigarettes9, this apparent association is at least partly confounded by cigarette smoking history.

Evidence for direct harms that are uniquely attributable to EC use is lacking. Under typical use conditions, without the overheating of coils or dry burning, ECs produce significantly lower exposures to harmful substances than do tobacco cigarettes6,7,8,10,11,12. In the US, the outbreak of e-cigarette or vaping-associated lung injury (EVALI) was initially attributed to nicotine e-cigarettes, but the true cause was later identified as a cutting agent—vitamin E acetate—in illicit cannabis vapes13,14. No definitive respiratory health effects uniquely attributable to vaping have been conclusively proven10,12,15,16.

The prevalence of e-cigarette use among non-smokers remains largely unexplored and depends heavily on data quality. Reliable evidence primarily comes from well-funded studies in the US and UK. For instance, the US NHIS 2021 reported that 2.9% of never-smokers currently use e-cigarettes17, while the 2024 ASH report from Great Britain indicated a prevalence of 1.6% among never-smokers18. A pooled analysis of 15 countries from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) shows that vaping is rare among adults who have never smoked, with only 0.1% of never-smokers currently using e-cigarettes19. However, some LMIC studies present an unclear picture, often due to sample issues. For example, a 2023 survey in Ecuador found that 44.2% of adult e-cigarette users had never smoked, though this sample was skewed towards healthcare workers20. Similarly, a 2019 Brazilian survey showed most e-cigarette users had never smoked, though usage was more common among younger adults21.

Given that existing reports of respiratory effects attributable to ECs are likely confounded by history of combustible tobacco use15,22,23, research on people without an established smoking history can be especially informative about whether vaping may have adverse respiratory effects. In a preliminary prospective study, daily users of ECs without a history of established smoking showed no significant alterations in lung function, respiratory symptoms, or exhaled breath nitric oxide (eNO)16,24. Furthermore, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans revealed no significant structural abnormalities in the lungs over an average observation period of 3.5 years16,24. However, the study faced limitations, such as a small sample size that may have included healthier e-cigarette users, and relatively short follow-up duration (3.5 years).

The current Vaping Effects: Real-world InTernAtional Surveillance (VERITAS) Study aims to fill this knowledge gap about long-term effects of exclusive vaping on lung health. To this end, the VERITAS study sampled adults without a history of established smoking or regular use of other tobacco/nicotine products, and compared frequency of respiratory symptoms among those who used ECs and those who did not. This study also evaluated the feasibility of gathering a large, global, distinct cohort of EC users for this and future research, and characterized these EC users’ patterns of use.

Methods

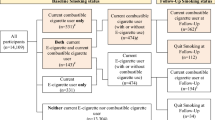

The outline of the study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The algorithm illustrates the sequential steps of the VERITAS survey process. Participants undergo pre-screening to determine their smoking history. Those with an established smoking history are excluded. Eligible participants are categorized into two cohorts: vapers (those who use vaping devices) and controls (non-users). Data collection includes sociodemographic information, smoking history, nicotine vaping product use behavior, and responses to the Respiratory Symptom Experience Scale (RSES) questionnaire.

Study design

The protocol of the VERITAS study has been described in detail previously25. Briefly, this study was a cross-sectional, internet-based survey conducted in six geopolitical world regions (Africa & Middle East, North America, Latin America & South America, Asia–Pacific, Western Europe, Eastern Europe). The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Review Board of the Dipartimento di Scienze della Formazione Sezione di Psicologia at the University of Catania (approval date, 25 November 2020). Data collection occurred between 10 May 2023 and 26 November 2023. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants

Based on sample size calculations and power analysis (see Supplement), this study targeted enrollment of 750 participants total (targets: Vapers Cohort = 500; Control Cohort = 250), approximately equally across regions.

This study recruited individuals 18 years and older who met the following criteria:

-

1.

Vapers Cohort (N = 491):

-

a.

Past 7-day use of at least one of three types of electronic cigarettes/vapes (disposables, rechargeable with replaceable pre-filled pods or cartridges (“pod/cartridge devices”), or rechargeable refillable with e-liquid (“refillable devices”));

-

b.

Smoked < 100 combustible cigarettes in their lifetime26 (including zero cigarettes) and having not smoked a cigarette in the past three months

-

c.

Never used, or never used than once weekly, any other tobacco/nicotine products.

-

a.

-

2.

Controls Cohort (N = 257): Satisfied the same criteria (b) and (c) above, and additionally reported having never used, or never fairly regularly used, any e-cigarette/vaping product.

Eligibility for inclusion in each cohort was assessed by a self-administered screening questionnaire that was administered to all individuals who gave informed consent to participate. Efforts were made to match Vapers and Controls in age and sex as closely as possible.

Procedures

Detailed recruitment and data collection described in the Supplement, and details of survey items have been published previously25. Briefly, participants in the Vapers Cohort were asked questions about their historical and current patterns of use of three types of vaping products: disposables, pod/cartridge devices, and refillable devices. For each vaping product category, data were collected on 12 outcomes, as applicable: (1) age of first use; (2) age of initiation of fairly regular use; (3) number of product units used in lifetime; (4) number of product use days in the past 30 days (P30D); (5) length of time (years, months) of fairly regular product use; (6) nicotine content of products use; (7) flavor categories used fairly regularly; (8) number of flavors used fairly regularly; (9) name of favorite flavor used in P30D; (10) number of product units used in P30D; (11) reasons for initiating product use (free text response); and (12) reasons for current product use (free text response).

All participants then completed the Respiratory Symptom Experience Scale (RSES), a validated scale that asks respondents to rate the frequency with which they had experienced five respiratory symptoms in P30D (25). The five symptoms rated were: (1) morning cough with phlegm or mucous; (2) cough frequently throughout the day; (3) shortness of breath that makes it difficult to do normal daily activities; (4) becoming easily winded during normal daily activities; and (5) wheezing or whistling in the chest at times when not exercising or doing other physically strenuous daily activities. Rating for each symptom was made on a 5-point scale: 1 = Never (0 out of the last 30 days); 2 = Rarely (1–5 days); 3 = Occasionally (6–15 days); 4 = Most days (16–29 days); 5 = Every day (all 30 out of the last 30 days). A mean RSES score is calculated by averaging the five item scores. The RSES can be found in the Supplement.

Lastly, questions assessed participants’ sex, country of residence, employment status, highest educational attainment, height, and weight. If needed, surveys were translated to accommodate non-English speakers, with data collected on the language used for the survey to note any nuances lost in translation. As a token of appreciation for participants’ time and contributions, participants were emailed instructions on how to claim a USD $30 Amazon or Take-A-Lot gift card upon survey completion.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses examined RSES scores and demographic characteristics among Vapers and Control Cohorts. The primary analysis examined differences in RSES score between the Vapers and Control Cohorts using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and adjusting for demographic differences (age, sex, education, and employment status). Exploratory follow-up ANCOVAs were conducted on each of the five RSES item scores. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The secondary objective of this study was to descriptively examine EC use history and EC use patterns among the Vapers Cohort, with respect to history of EC use, past 30-day use patterns, and characteristics of EC products used. Further analyses explored data filtered or stratified by EC device type. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 27.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Vapers (N = 491) and Controls (N = 257) were similar on three of the four assessed demographic variables: the majority of each cohort were aged 25–44 years, were employed full-time (≥ 35 h per week), and had some college/university education or has obtained a Bachelor’s degree or higher (Table 1). Vapers were more likely than Controls to be male (54.0% vs 48.6%, respectively).

Respiratory symptoms

Figure 2 shows the distribution of symptom frequency for each RSES item. Notably, the majority of both Vapers and Control Cohorts (85% or more) reported “never” or “rarely” experiencing each of the five symptoms, which falls below the optimal cut-off point for differentiating participants with (versus without) a diagnosis of respiratory disease27. Experiencing occasional symptoms was more common in Vapers than Controls (6.3–12.2% vs. 2.3–7.0%, respectively, across symptoms), but experiencing symptoms most days or everyday was equally rare or non-existent in both groups (0–3.1% for Vapers and 0–1.6% for Controls).

A one-way between-subjects ANCOVA showed a significant difference in mean RSES score between the Vapers and Control Cohorts, after controlling for the effects of age, sex, employment status, and education level, F (1, 725) = 18.59, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.025. Covariate-adjusted RSES mean scores indicated Vapers (M = 1.61, SE = 0.02) experienced a higher frequency of respiratory symptoms compared to Controls (M = 1.43, SE = 0.03) (mean diff. = 0.18) (Table 2). However, the effect size was small, each cohort’s RSES mean score was close to the minimum scale score of 1 (“never”), and the mean difference between cohorts was below the threshold (0.57) for a clinincally meaningful difference27. Moreover, vapers’ RSES score also fell below the optimal cut-off point of 2 (i.e. “rarely”) for differentiating participants with (versus without) a diagnosis of respiratory disease27.

Exploratory ANCOVAs conducted separately on each of the five RSES item scores as the dependent variable revealed similarly statistically significant main effects of cohort, with the exception of the ANCOVA conducted on Item 3 score (‘shortness of breath’), which revealed a non-significant covariate-adjusted main effect of cohort ((F (1, 725) = 3.34, p = 0.068, partial η2 = 0.005). Vapers reported higher mean scores on each of the five RSES items, with the highest mean score observed on Item 1 (‘morning cough with phlegm or mucous’; M = 1.73) and the highest mean difference score observed on Item 5 (‘wheezing or whistling in the chest while resting’; mean diff. = 0.24).

History of cigarette smoking and other tobacco/nicotine product use

Though by virtue of incusion in this study, no participants smoked > 100 cigaretes/lifetime; however, the Vapers Cohort more often reported former experimentation with cigarettes (30.8% vs. 12.1% the Control Cohort, Supplement, Table S1). Additionally, a higher proportion of the Vapers Cohort reported use of any other tobacco/nicotine product (18.1% vs. 5.8%).

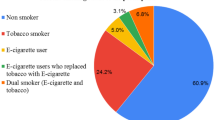

EC use patterns

The Vapers Cohort most often used disposable ECs in the past 7 days (63.7%, n = 313), followed by refillable devices (29.1%, n = 143) and pod/cartridge devices (RPFPC, 13.8%, n = 68). A similar preference for disposable ECs was observed when asking about use over different time frames (ever use, ever regular use, and use in P30D) (Supplement, Table S2).

Supplementary Table S3 presents detailed EC use history and product characteristics by primary device type in the past 7 days. Briefly, there was substantial overlap in the use of different EC device types: ~ 13–35% of each group reported also using another device type. There was a wide distribution of use-days in P30D, with ~ 12–19% of the Vapers Cohort using ECs on only 1–5 days, and 12–39% using daily; daily use was more common among those who used refillable devices. Those who used refillable devices also more often reported that their ECs contained nicotine (56%, vs. 28–44% for those who used other device types). While overall, most of the Vapers Cohort reported using ECs for between 1 and 5 years, those who used refillable ECs were more likely to report longer durations of use (25% reported > 5 years, vs. ~ 6–16% of those using different device types). The majority of the Vapers Cohort used multiple flavors in P30D (~ 60–80% across device types used 2+ flavors). Fruit was the most commonly used flavor, used by ~ 70–80% of EC users across device types. Use of tobacco flavor was uncommon (~ 10% or less across device types).

Discussion

This current VERITAS study provides novel evidence on whether e-cigarette use is uniquely associated with respiratory symptoms, as it is the first such investigation among a large, global cohort of people who do not have an established history of combustible tobacco use. Vapers reported a significantly higher frequency of respiratory symptoms over P30D; however, the difference in RSES score was 0.18, which is approximately one-third as small as the minimal clinically important difference of 0.57 for this scoring27. Furthermore, the absolute frequency of these respiratory symptoms among vapers was relatively low, with 20.6% (101 out of 491) of the vaping cohort and 49.4% (127 out of 257) of the control cohort reporting never experiencing any symptoms. Yet, comparable proportions of both the vaping (83.3%) and control cohorts (88.4%) reported “never” or “rarely” experiencing symptoms, indicating that more frequenty symptoms were rarely experienced by both groups. While vapers had higher rates of “occasionally” experiencing symptoms, this could be partly due to the transient irritant effects of vaping28,29,30. These observations align with the results of a small, prospective clinical study involving daily vapers who have never smoked. This study reported no regular respiratory symptoms and no significant changes in lung function, inflammation, or structural anomalies as detected in lung CT scans24.

Prior research on toxicology and animal models has raised concerns that EC use could pose risks for respiratory illness31, though it is not clear whether these findings generalize to human health32. Direct evidence from human subjects research is more ambiguous, as, due to ethical considerations, most of this evidence relies on observational data. On one hand, prior observational studies have reported that the prevalence of diagnosed respiratory diseases is higher in EC users than non-users6,7,8. However, since the majority of adult EC users either currently smoke or formerly smoked cigarettes33,34 and as cigarette smoking is a well-known cause of respiratory illness35, it is highly likely that the apparent association between ECs and respiratory symptoms is confounded by cigarette smoking history22,35,36. The current study avoids this limitation by focusing on EC users without a history of established or recent cigarette smoking, and thus provides novel evidence that EC use in the absence of a smoking history is not associated with clinically meaningful increase in frequency of respiratory symptoms. These findings also shed light on the ambiguity in prior research: since EC use is associated with only a small absolute increase in frequency of respiratory symptoms, far below the difference associated with any respiratory diagnoses, it is likely that differences in the likelihood of diagnosed (i.e. clinically relevant) respiratory illness reported in prior studies (6–8) are attributable to significant confounding by unmeasured or uncontrolled effects of individuals’ cigarette smoking history.

With respect to EC use characteristics, the majority of the Vapers Cohort primarily used disposable ECs (64% in P30D), and approximately 30% used refillable devices; pod/cartridge device use was least common, at approximately 15%. Use of multiple types of ECs was common, however, with ~ 13–35% of Vapers reporting using a second EC device type in addition to their primary. The Vapers Cohort had a wide range in frequency of use, with ~ 12–19% (across EC device types) using on only 1–5 days in P30D, and 12–39% reporting daily use. In general, users of refillable devices had use patterns characteristic of heavier use, including more frequent use and having used for a longer duration. Use of non-tobacco flavors was also common across device types—primarily fruit flavors—as was use of multiple flavors (~ 70–80%), especially among users of disposable ECs. This aligns with other recent research showing that disposables are the most common EC device type in recent years37,38 and that adult vapers prefer fruit and sweet flavors over traditional cigarette flavors such as tobacco and menthol37,39.

The study findings should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. Due to its cross-sectional and observational nature, the current study cannot establish causality between EC use and respiratory symptoms. Some readers may interpret the findings as evidence that vaping increases respiratory symptoms. However, it is equally plausible that individuals with pre-existing respiratory symptoms, due to other factors, are more likely to take up vaping instead of smoking (i.e. reverse causation). There were also other differences between the Vaper and Control Cohorts that could explain the small absolute, but statistically significant, difference in respiratory symptom frequency. The Vaper Cohort, for example, reported slightly more extensive cigarette experimentation (though not rising to the level of established use), and slightly more often use of other tobacco and nicotine products on an occasional basis (versus never). Additionally, there could be other confounding factors that were not measured by the survey (e.g., exposure to environmental or occupational pollutants). Another limitation is that vaping of other substances (e.g., cannabis) was not assessed; this may be important as another possible confounding factor, and could also introduce uncertainty in self-reported vaping behavior (e.g., it is possible that reported use of zero-nicotine EC products could reflect vaping of cannabis or other substances). There was limited information on long-term EC use in the current Vapers Cohort, who predominantly vaped for 5 years or less. Finally, the accuracy of responses may be limited due to recall bias and/or misattribution of EC product characteristics.

This study also has notable strengths: this is a novel study focusing on EC users without an established smoking history, which overcomes serious limitations of existing literature and provides preliminary evidence on possible frequency of respiratory symptoms that may be uniquely attributable to EC use. This study is the first, to our knowledge, to focus on this population, and has a large sample drawn from six geopolitical world regions.

In conclusion, this study provides important preliminary evidence that EC use alone (i.e., without a history of established cigarette smoking or recent or regular use of other tobacco or nicotine products) is associated with a small absolute increase in self-reported frequency of respiratory symptoms that is not clinically different from an experience of respiratory symptoms reported by individuals who have never regularly used ECs or any other tobacco or nicotine products. Disposable ECs and use of multiple flavors (predominantly fruit) were the most commonly used product characteristics. This cross-sectional evidence provides a strong basis for mounting longitudinal assessments of intra-individual change in respiratory symptoms among cohorts of EC users with no established smoking or other tobacco or nicotine product use history.

Data availability

The raw data presented in this study are not publicly available in order to protect participant confidentiality. However, data are available from the corresponding author Riccardo Polosa upon reasonable request. For any data or questions regarding the study, please contact polosa@unict.it.

References

Lindson, N. et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1(1), CD010216. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub8 (2024).

O’Leary, R. & Polosa, R. Tobacco harm reduction in the 21st century. Drugs Alcohol Today. 20, 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-02-2020-0007 (2020).

Patel, D. et al. Reasons for current E-cigarette use among US adults. Prev. Med. 93, 14–20 (2016).

DiPiazza, J. et al. Sensory experiences and cues among E-cigarette users. Harm Reduct. J. 17, 1–11 (2020).

Etter, J.-F. Throat hit in users of the electronic cigarette: An exploratory study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 30, 93 (2016).

Bhatta, D. N. & Glantz, S. A. Association of e-cigarette use with respiratory disease among adults: A longitudinal analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 58, 182–190 (2020).

Cordova, J. et al. Tobacco use profiles by respiratory disorder status for adults in the wave 1-wave 4 population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Prev. Med. Rep. 30, 102016 (2022).

Paulin, L. M. et al. Association of tobacco product use with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) prevalence and incidence in Waves 1 through 5 (2013–2019) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Respir. Res. 23, 273 (2022).

Delnevo, C. D. et al. Patterns of electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob. Res. 18, 715–719 (2016).

Caruso, M. et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems exhibit reduced bronchial epithelial cells toxicity compared to cigarette: The Replica Project. Sci. Rep. 11, 24182 (2021).

Emma, R. et al. Cytotoxicity, mutagenicity and genotoxicity of electronic cigarettes emission aerosols compared to cigarette smoke: The REPLICA project. Sci. Rep. 13, 17859 (2023).

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington (DC) (2018).

Hall, W., Gartner, C. & Bonevski, B. Lessons from the public health responses to the US outbreak of vaping-related lung injury. Addiction. 116, 985–993 (2021).

Pesko, M.F. et al. United States public health officials need to correct e‐cigarette health misinformation: Wiley Online Library (2023).

Hajat, C. et al. A scoping review of studies on the health impact of electronic nicotine delivery systems. Intern. Emerg. Med. 17(1), 241–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-021-02835-4 (2022).

Qureshi, M. A., Vernooij, R. W. M., La Rosa, G. R. M., Polosa, R. & O’Leary, R. Respiratory health effects of e-cigarette substitution for tobacco cigarettes: A systematic review. Harm. Reduct. J. 20, 143 (2023).

Erhabor, J. et al. E-cigarette use among US adults in the 2021 behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey. JAMA Netw. Open. 6(11), e2340859. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.40859 (2023).

https://ash.org.uk/uploads/Use-of-vapes-among-adults-in-Great-Britain-2024.pdf?v=1723194891

Sreeramareddy, C. T. & Manoharan, A. Awareness about and e-cigarette use among adults in 15 low- and middle-income countries, 2014–2018 estimates from global adult tobacco surveys. Nicotine Tob. Res. 24(7), 1095–1103. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab269 (2022).

Izquierdo-Condoy, J. S. et al. E-cigarette use among Ecuadorian adults: A national cross-sectional study on use rates, perceptions, and associated factors. Tob. Induc. Dis. 31, 22. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/187878 (2024).

Bertoni, N., Cavalcante, T. M., Souza, M. C. & Szklo, A. S. Prevalence of electronic nicotine delivery systems and waterpipe use in Brazil: Where are we going?. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 24(suppl 2), e210007. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720210007.supl.2 (2021).

Polosa, R. Electronic cigarette use and harm reversal: Emerging evidence in the lung. BMC Med. 13, 54 (2015).

Polosa, R. et al. Impact of exclusive e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products use on muco-ciliary clearance. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 12, 20406223211035268 (2021).

Polosa, R. et al. Health impact of E-cigarettes: A prospective 35-year study of regular daily users who have never smoked. Sci. Rep. 7, 13825 (2017).

Zamora Goicoechea, J. et al. A global health survey of people who vape but never smoked: Protocol for the VERITAS (Vaping Effects: Real-World International Surveillance) Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 13, e54236. https://doi.org/10.2196/54236 (2024).

Malarcher, A., Shah, N., Tynan, M., Maurice, E. & Rock, V. State-specific secondhand smoke exposure and current cigarette smoking among adults-United States, 2008. MMWR. 58, 1232–1235 (2009).

Shiffman, S., McCaffrey, S. A., Hannon, M. J., Goldenson, N. I. & Black, R. A. A new questionnaire to assess respiratory symptoms (The Respiratory Symptom Experience Scale): Quantitative psychometric assessment and validation study. JMIR Form Res. 7, e44036 (2023).

Gualano, M. R. et al. Electronic cigarettes: Assessing the efficacy and the adverse effects through a systematic review of published studies. J. Pub. Health. 37, 488–497. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdu055 (2015).

Polosa, R. et al. Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e-Cigarette) on smoking reduction and cessation: A prospective 6-month pilot study. BMC Pub. Health. 11, 786. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-786 (2011).

Caponnetto, P. et al. EffiCiency and Safety of an eLectronic cigAreTte (ECLAT) as tobacco cigarettes substitute: A prospective 12-month randomized control design study. PLoS One. 8, e66317. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066317 (2013).

Gotts, J. E., Jordt, S.-E., McConnell, R. & Tarran, R. What are the respiratory effects of e-cigarettes?. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed). 366, l5275. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5275 (2019).

Polosa, R., O’Leary, R., Tashkin, D., Emma, R. & Caruso, M. The effect of e-cigarette aerosol emissions on respiratory health: A narrative review. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 13, 899–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2019.1649146 (2019).

Bandi, P. et al. Changes in e-cigarette use among US adults, 2019–2021. Am. J. Prev. Med. 65, 322–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2023.02.026 (2023).

Action on Smoking and Health (ASH). Headline results ASH Smokefree GB adults and youth survey results 2023. UK2023. https://ash.org.uk/uploads/Headline-results-ASH-Smokefree-GB-adults-and-youth-survey-results-2023.pdf

Office of the Surgeon General, Office on Smoking. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA). (2004).

Sargent, J. D. et al. Tobacco use and respiratory symptoms among adults: Findings from the longitudinal Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study 2014–2016. Nicotine Tob. Res. 24, 1607–1618 (2022).

Ali, F. R. M. et al. E-cigarette unit sales by product and flavor type, and top-selling brands, United States, 2020–2022. MMWR. 72, 672–677. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7225a1 (2023).

Jongenelis, M. I. E-cigarette product preferences of Australian adolescent and adult users: A 2022 study. BMC Pub. Health. 23, 220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15142-8 (2023).

Gravely, S. et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) flavours and devices used by adults before and after the 2020 US FDA ENDS enforcement priority: Findings from the 2018 and 2020 US ITC Smoking and Vaping Surveys. Tob. Control. 31, s167–s175. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2022-057445 (2022).

Funding

This investigator-initiated research is sponsored by ECLAT Srl., a spin-off of the University of Catania, through a competitive grant from Global Action to End Smoking (formerly known as Foundation for Smoke-Free World), an independent, U.S. nonprofit 501(c)(3) grantmaking organization, accelerating science-based efforts worldwide to end the smoking epidemic. Global Action played no role in designing, implementing, data analysis, or interpretation of the study results. The contents, selection, and presentation of facts, as well as any opinions expressed, are the sole responsibility of the authors and should not be regarded as reflecting the positions of Global Action to End Smoking. ECLAT Srl is a research-based company that delivers solutions to global health problems with particular emphasis on harm minimization and technological innovation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JZG, CR, MC, PC, VT, and RP conceptualized the study. JZG, AB, CCLJ, AM, YK, MS, and MC recruited participants and collected data. JZG was the project administrator. JZG, CR, AS, and RP analyzed the data and created figures. JZG, GC, PC, VT, AS, and RP provided supervision and oversight. RP provided funding acquisition. JZG, AS, and RP together wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors critically revised and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JZG is the President of Asovape Costa Rica, a Pro-Harm Reduction consumer organization; President of ARDT Iberoamerica, an alliance of Pro-Harm Reduction consumer organizations in Latin America, Spain, and Portugal; Director of Social Media and Audiovisual Producer of INNCO , a global coalition of Pro-Harm Reduction consumer organizations, which received funding from the Foundation for a Smokefree World (FSFW); and a recipient of a scholarship from Knowledge-Action-Change, which received funding from the Foundation for a Smokefree World (FSFW). None of these organizations had any role in, or oversight, of this study. AB is serving Pro Bono as Vice President, American Vapor Manufacturers —Prescott, AZ. Serving Pro Bono as Ambassador, World Vapers Alliance Serving Pro Bono as President, South Carolina Vapor Association, Charleston, SC JJCL is the President of the board of Mexico y el Mundo Vapeando O.N.G. and a scholarship recipient from Knowledge-Action-Change, which received funding from the Foundation for a Smokefree World (FSFW). None of these organizations had any role in, or oversight, of this study. Court Lawyer for vaping industries AM is a recipient of two scholarships from Knowledge-Action-Change, which receives funding from the Foundation for a Smokefree World (FSFW). This organisation has not had any role in, or oversight, of this study. KY is the Co-Founder of the Consumer Advocacy movement Vaping Saved My Life (VSML) Act as a consultant for the Vapour Products Association of South Africa (VPASA), an industry association for vapor product manufacturers and retailers. A member of the Advisory Board for the World Vapers Alliance (W.V.A.), a global consumer advocacy group. Recipient of the Tobacco Harm Reduction Scholarship Programme and Advanced Scholarship Programme from Knowledge Action Change(K.A.C.). K.A.C. receives funding from the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. MS is a co-founder of Smoke-Free Baltic tobacco harm reduction initiative and a recipient of a scholarship from Knowledge—Action—Change, which received funding from the Foundation for a Smokefree World (FSFW). None of these organizations had any role in, or oversight, of this study. CR is Director of Russell Burnett Research and Consultancy Ltd, which has received research funding and/or consultancy fees from manufacturers of e-cigarettes/vaping products to conduct or consult on studies of individuals’ perceptions and use of tobacco and nicotine products, including e-cigarettes/vaping products. Michael Coughlan is a recipient of a scholarship from Knowledge-Action-Change, which received funding from the Foundation for a Smokefree World (FSFW). None of these organizations had any role in, or oversight, of this study. AS provides consulting services on tobacco harm reduction to Juul Labs, Inc. (JLI) through PinneyAssociates. She also individually provides consulting services on behavioral science to the Center of Excellence for the Acceleration of Harm Reduction (CoEHAR) through ECLAT Srl., which received funding from the Foundation for a Smokefree World (FSFW). None of these funders had any role in, or oversight, of this study. GC declares no conflict. PC declares no conflict. VT declares no conflict. RP is full tenured professor of Internal Medicine at the University of Catania (Italy) and Medical Director of the Institute for Internal Medicine and Clinical Immunology at the same University. He has received grants from U-BIOPRED and AIR-PROM, Integral Rheumatology & Immunology Specialists Network (IRIS), Foundation for a Smoke Free World, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, CV Therapeutics, NeuroSearch A/S, Sandoz, Merk Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Arbi Group Srl., Duska Therapeutics, Forest Laboratories, Ministero dell Universita’ e della Ricerca (MUR) Bando PNRR 3277/2021 (CUP E63C22000900006) and 341/2022 (CUP E63C22002080006), funded by NextGenerationEU of the European Union (EU), and the ministerial grant PON REACT-EU 2021 GREEN- Bando 3411/2021 by Ministero dell Universita’ e (MUR) – PNRR EU Community. He is founder of the Center for Tobacco Prevention and Treatment (CPCT) at the University of Catania and of the Center of Excellence for the Acceleration of Harm Reduction at the same university. He receives consultancy fees from Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Duska Therapeutics, Forest Laboratories, CV Therapeutics, Sermo Inc., GRG Health, Clarivate Analytics, Guidepoint Expert Network, and GLG Group. He receives textbooks royalties from Elsevier. He is also involved in a patent application for ECLAT Srl. He is a pro bono scientific advisor for Lega Italiana Anti Fumo (LIAF) and the International Network of Nicotine Consumers Organizations (INNCO); and he is Chair of the European Technical Committee for Standardization on “Requirements and test methods for emissions of electronic cigarettes” (CEN/TC 437; WG4).

Ethical approval

The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Review Board of the Dipartimento di Scienze della Formazione Sezione di Psicologia at the University of Catania (approval date, 25 November 2020). All participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goicoechea, J.Z., Boughner, A., Lee, J.J.C. et al. Respiratory symptoms among e-cigarette users without an established smoking history in the VERITAS cohort. Sci Rep 14, 28549 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80221-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80221-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Differences in respiratory wheezing between current exclusive e-cigarette users, current exclusive cigarette smokers, and never users of either product: findings from a population-based study

Harm Reduction Journal (2025)

-

Assessing the Italian version of the respiratory symptom experience scale (IT-RSES) in smokers and former smokers: a validation study

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

When meta-analysis misleads: the need for methodological integrity in e-cigarette research

Internal and Emergency Medicine (2025)

-

The emerging role of oral nicotine pouches in tobacco harm reduction

Internal and Emergency Medicine (2025)

-

Association between electronic cigarette use and respiratory outcomes among people with no established smoking history: a comprehensive review and critical appraisal

Internal and Emergency Medicine (2025)