Abstract

Due to demographic changes, a growing number of elderly patients with comorbidities will require spine surgery in the next decades. However, age and multimorbidity have been associated with considerably worse postoperative outcomes, and is often associated with surgical invasiveness. Full-endoscopic spine-surgery (FESS), as a cornerstone of contemporary minimally invasive surgery, has the potential to mitigate some of these disparities. Thus, we conducted an analysis of all FESS cases at a national center. Utilizing the Charlson Comorbidity index (CCI) ≥ 3 as a frailty surrogate we separated patients in two groups for patients with and without comorbidities. Patients with (CCI) ≥ 3 exhibited a higher age (p < 0.001), and number of comorbidities (p < 0.001) than the control group. Thereafter, a propensity score matching was done to adjust for potential confounders. Postoperative safety measures in emergency department utilization, and clinic readmission did not significantly differ between the groups. Furthermore, patients of both groups reported similar postoperative pain improvements. However, patients with a (CCI) ≥ 3 were treated as inpatients more often (p < 0.001), had a higher length of stay (p < 0.001) and a smaller functional improvement after at a chronic postoperative timepoint (p = 0.045). The results underline safety and efficacy of FESS in patients with comorbidities. Additionally, they provide guidance for preoperative patient counselling and resource utilization when applying FESS in frail patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing number of degenerative spine diseases, due to demographic ageing, will be the leading cause of several challenges for global healthcare systems, in the coming decades. Due to an emerging number of indications to address pathologies in the aging spine, limited hospital resources run the risk of getting overwhelmed by a rising number of spine surgeries1. Frail and elderly patients are especially susceptible to adverse outcomes following elective spine surgery due to destabilizing stressors and a reduced ability to regulate homeostasis2. Various frailty assessments and surrogates have shown a correlation between patient age, comorbidity risk and frailty status3,4. One such frailty surrogatesis the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which is recognized by clinicians as an accurate predictor of spinal surgical outcomes in susceptible patients5,6,7. As opposed to other frailty surrogates (e.g. MFI), the CCI includes age as an item which has substantial relevance for preoperative patient counseling and selection. Frailty is associated with a multitude of adverse outcomes and quality surrogates after spine surgery including mortality, surgical complications, reoperation, wound complications, non-home discharge, length of stay, and hospital readmissions8,9,10,11,12,13. Such negative post-operative complications occur at a higher likelihood when paired with considerable surgical invasiveness as well as advanced age14. Therefore, frail and elderly patients might yield additional benefits from a reduction in surgical invasiveness when compared to a younger population.

Full-endoscopic spine-surgery (FESS) presents an emerging surgical technique that minimizes the invasiveness of spinal surgery15,16. Previous reports indicate efficacy and safety of this approach17,18. FESS drastically reduces postoperative wound-related complications and virtually eradicates surgery site infection19, while also expediting postoperative recovery with significant pain alleviation within the first few days20. Additionally, FESS facilitates awake anesthesia which reduces anesthetic complications, more notably in frail populations21,22. In doing so, FESS has shown success in minimizing wound-related issues and functional disparities in the postoperative recovery for obese and non-obese patients23,24. Thus, FESS enables an instant postoperative mobilization which might yield further benefits in frail patients.

As of today, only limited research analyzing the intersection of frailty and FESS exists. Hence, the aim of this work was to assess the safety profile of FESS in a frail population as well as outlining potential differences in recovery patterns when compared to a non-frail population. For this study, the CCI was utilized as a frailty surrogate.

Materials and methods

Data collection

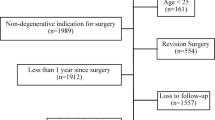

This study was a retrospective analysis of patient data prospectively obtained at one national center. Inclusion criteria encompassed patients aged 18 years and above who had undergone FESS for degenerative pathologies of the lumbar spine (including the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral junction) between March 2014 and May 2023. All surgeries were performed by the same, experienced surgeon. Data was retrieved through the patients’ electronic medical records. FESS, in this context, was defined as the utilization of a uniportal working channel endoscope equipped with a light source, camera, and an irrigation channel. We excluded all patients with traumatic and malignant pathologies, as well as procedures involving a hybrid approach that integrated minimally invasive or open techniques, fusion surgeries, and cervical or thoracic surgeries. All data were obtained pseudonymously in accordance with national law and the declaration of Helsinki. Written and informed consent were obtained from all patients prior to the surgery. Data was obtained following the approval of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Washington (IRB No. 07742). The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Outcomes

Demographic parameters encompassed sex, age, race, and Body Mass Index (BMI). The Charlson Comorbidity index was utilized as an indicator for frailty25. Furthermore, comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, depression, smoking status, chronic heart failure, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were included and analyzed separately. Surgical details covered anatomical location, the number of operated levels, and surgery duration. Surgeries were divided into decompression surgeries for spinal canal stenosis, and discectomies for disc herniations. Hospitalization data and postoperative quality indicators, including the duration of stay, emergency department utilization, clinic readmission, and surgical revision, were also gathered. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were collected prospectively at any in-person follow-up, which included a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for back pain and in the affected extremity, as well as the Oswestry Disability Index as a functional outcome26. For analysis, a CCI ≥ 3 as a surrogate for multimorbidity and frailty was used as a cut-off threshold for the frail and non-frail group25. The primary study outcomes included length of stay, occurrence of emergency department utilization, clinic readmissions, and surgical revisions within ninety days post-surgery. Additionally, PROMs were compared postoperatively between the frail-group and the non-frail-group at the two-week, three-month, and chronic timepoint. Chronic was defined as at least six months after the initial surgery.

All data acquisition procedures adhered to the Institutional Review Board’s approval. Pseudonymous data collection was conducted in compliance with national law and the Declaration of Helsinki. Written and informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to the surgery.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (Version 9.5.0; GraphPad Software, Boston, MA). Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD), and categorical variables are expressed as the number of cases with percentages. Groups were compared using Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, Chi-square, and Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. A significance level of p < 0.05 was applied to all analyses. Minimum Clinically Important Difference (MCID) threshold was set at 1.2 points for back pain and 1.6 points for leg pain. An improvement of 30% in the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) was considered an MCID27,28. MCID calculations were performed at the two-week, three-month, and the chronic timepoint. Thereafter, a multivariate regression model for MCID at the given timepoints adjusting for demographic and surgical parameters was constructed. Lastly, propensity-score matching between our cohorts was performed using a “nearest-neighbor”-method package with a small caliper of 0.01 to ensure tight matching. Matches were based on clinically pertinent parameters including patient sex, BMI, number of surgical levels, and the type of surgery (i.e. discectomy or decompression). Univariate analyses were then repeated for this new matched cohort.

Results

Patient population

In total, 585 patients met the inclusion criteria; of those, 329 patients were assigned to the control group, whereas 256 patients were assigned to the group with a CCI ≥ 3. After group comparison, patients of the CCI ≥ 3 group exhibited significantly higher age (69.4 ± 10.3 vs. 48.8 ± 13.0; p < 0.001; frail group vs. control group in the following), and a higher number of comorbidities (6.2 ± 4.3 vs. 3.03 ± 4.3; p < 0.001) when compared to the control group. Patients with a CCI ≥ 3 underwent FESS decompression (p < 0.001) and multilevel surgery (p < 0.001) more frequently than the control group. Propensity matching yielded satisfactory results for patient matching of 206 matched pairs. Matching successfully eliminated discrepancies between the groups regarding race (p > 0.99), operated levels (p = 0.87), and surgical approaches (p = 0.97). As expected, significant differences regarding age (p < 0.01) and number of comorbidities (p < 0.01) remained after propensity matching (Table 1).

In the initial analysis significant differences showed between the groups regarding intraoperative blood loss (7.81 ± 6.65 vs. 5.71 ± 5.94; p < 0.01) and the duration of surgery (168.8 ± 75.3 vs. 143.6 ± 66.3; p < 0.01). Those differences did not remain statistically significant after propensity matching. Postoperatively, patients with a CCI ≥ 3 were treated as inpatients significantly more often (p < 0.001) and had a significantly higher number of days stayed in the hospital (0.7 ± 1.5 vs. 0.4 ± 1.2; p < 0.001), which stayed statistically significant after propensity matching (p < 0.01 and p = 0.05). All patients were discharged home postoperatively. Regarding post-discharge clinic utilization, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups for any postoperative emergency department utilization (p = 0.39), clinic readmission (p > 0.99), and surgical revision (p = 0.514). However, after propensity matching, significant differences showed regarding surgical revisions for those patients with CCI ≥ 3 (1.0% vs. 2.4%; p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Functional outcomes

In total, 177 patients from the control group and 114 from the intervention group reported functional outcomes 3 months after the surgery. At the chronic timepoint 102 patients reported functional outcomes for the control group and 73 in the group with CCI ≥ 3 (Fig. 1). At baseline, no statistically significant differences were observable between the groups for back pain, leg pain, and ODI. Patients with CCI ≥ 3 patients showed a slower functional recovery as expressed by a significantly smaller ODI improvement at the two-week timepoint (∆3.52 ± 10.5 vs. ∆5.37 ± 10.2, p = 0.044). At the chronic timepoint, patients with CCI ≥ 3 reported significantly smaller benefits in ODI improvement when compared to the control group (∆5.49 ± 10.7 vs. ∆8.11 ± 10.6; p = 0.047) which translated into a significantly smaller probability of achieving an MCID (p = 0.018) in patients with CCI ≥ 3. This remained statistically significant after propensity matching (p = 0.02). No statistically significant differences were found for pain alleviation at any timepoint (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis revealed a CCI ≥ 3 to be significantly correlated with reported MCID for ODI (OR 0.5, p = 0.023, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.9) at the chronic timepoint. Likewise, a preoperatively diagnosed depression showed significant correlation with reported MCID for back pain (OR 0.4, p = 0.25, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.9), and female sex with reported MCID for leg pain (OR 0.4, p = 0.008, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.8) (Table 4).

Discussion

The presented study underlines the feasibility and safety of FESS in patients with relevant CCI scores. Furthermore, the results indicate disparities in reported benefits of the surgical procedure. While pain alleviation following FESS was similar between patients with CCI ≥ 3 and the control group, patients with CCI ≥ 3 appear to yield lower functional benefits at chronic postoperative timepoints.

Demographic aging will inevitably change the patient population undergoing elective spine surgery. Consequently, it is imperative that contemporary spine surgery establishes safe and effective surgical procedures for spinal pathologies in multimorbid patients while addressing their increased risk of adverse events8,9,10,11,12. Furthermore, all surgical considerations need to take resource scarcity in global healthcare systems into account1. FESS has established itself as a minimally invasive surgical technique that can safely be performed in an outpatient setting29. Regarding the intersection of multimorbidity, age, and FESS, only a little body of research exists that has shown feasibility and efficacy in an aged population30. Compared to open procedures, FESS has been associated with a shorter length of hospital stay and lower non-home discharge in patients with comorbidities31. However, there is a lack of research comparing those patient populations undergoing FESS. Our study corroborates the previously reported feasibility, safety, and efficacy of FESS in patients with comorbidities and the elderly. The cutoff value of a CCI ≥ 3 is substantiated by the patient populations’ demographics reflected by a higher age as well as age-associated comorbidities. Most importantly, no differences in postoperative safety measures and quality indicators were observable between the cohorts. Emergency department utilization, clinic readmission, and surgical revisions as essential point-of-care measures were similar between groups32. When compared to other surgical approaches, these findings add potential advantages of a minimized surgical invasiveness since patients with medical conditions have shown higher readmission rates, perioperative complications, and discharge deposition6,12. In the presented cohort, all patients were discharged home.

Due to those patients with CCI ≥ 3 being among an aged population, naturally, this cohort required inpatient treatment more often and consequentially had a higher length of stay which is supported by the literature in traditional spine surgery11. However, after the propensity matching, a significant difference showed regarding the surgical revision rates between the groups.

In addition, pathophysiological differences between the two groups were observed. Patients with CCI ≥ 3 more frequently underwent decompression for multilevel pathologies while the control population underwent single level surgery due to spinal stenosis and disc herniation at similar rates33,34,35. Interestingly, patients with CCI ≥ 3 who seemingly underwent more complex multilevel procedures reported similar postoperative pain improvements at any timepoint. However, patients with CCI ≥ 3 reported a significantly lower ODI improvement and MCID at the chronic timepoint. This finding is supported by studies indicating smaller ODI improvements for frail patients undergoing lumbar fusion and by our multivariate analysis36,37. While radiographic parameters were not included in the analysis, one potential explanation for this could be a more complex underlying pathology in the aging spine. Younger patients typically present with single level disc herniations, as evidenced by the overall higher number of discectomies in the control cohort. As opposed to elderly, often times presenting with multiple pathologies, including degenerative scoliosis and sagittal malalignment, which is especially prevalent in a frail population38,39. In spite of feasibility studies and case series of FESS fusion surgeries, a standardized surgical approach for the correction of sagittal malalignments remains a limitation of FESS40,41. For our cohort, some of the elderly patients might have yielded additional benefits from a spinal realignment procedure.

Our reported results are essential for preoperative patient counselling as they elucidate different recovery patterns. While multimorbid patients can expect significant improvements in back and leg pain after the surgery, the improvement of low-back disability is limited by their age-associated overall condition.

The multivariate analysis indicated a significant correlation between preoperative depression and the achievement of an MCID for back pain at the chronic timepoint. A high prevalence of depression in patients with chronic back pain has been reported42. Notably, depressed patients appear to yield smaller benefits from spine surgery than their non-depressed counterparts43. This finding is supported by several studies identifying preoperative depression as a predictor for lower patient satisfaction and higher adverse events surrounding spine surgery43,44,45. The intersection of backpain is multifaceted with implications for both preoperative counselling and postoperative rehabilitation. While depressed patients report overall improvements for both back pain, and depression scores, implications of the depressive disorder need to be discussed with the patients preoperatively46. Moreover, female sex and more operated levels had a significant correlation with reported MCID for leg pain in the multivariate analysis. While complexity of the surgery and multilevel pathology appear to be plausible explanations for a lower MCID in this population, there is an ongoing debate about sex affecting functional outcomes after spine surgery and its’ clinical significance47,48,49. While the significance of sex disparities in the presented study should be interpreted with caution, sex differences in perceived postoperative pain improvement is essential for comprehensive patient counselling.

FESS demonstrates a minimally invasive approach that benefits frail patients with regard to the populations increased susceptibility to surgery complications previously described. FESS in frail patients remains a safe and efficient method to sufficiently address spinal pathologies while substantially reducing surgical invasiveness.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge that this work has limitations. The retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data implies selection bias. Furthermore, data assessments were conducted at the in-person follow-ups resulting in relevant loss-to follow-up for reported functional outcomes. This is especially relevant as many patients don’t attend their 3-month or chronic follow-ups which affects completeness of the data, presumably mainly for those patients who are doing well and thus underestimating the actual postoperative pain and functional improvements. In our cohort, only approximately half of the patients had an follow-up after 3 months, and only one third of the patients after 6 months, which presents a key limitation for the functional outcomes of our patients at the given timepoints. This could be prevented with modern tools (e.g. smartphone applications) that enable asynchronous patient feedback to generate larger cohorts regarding secondary outcomes following FESS50. The single-center, single-surgeon design of the study limits the generalizability of the results. Lastly, the grouping presents a limitation itself as numerous assessments for frailty and multimorbidity exist. For this study, the CCI was chosen as it includes a broad number of comorbidities as well as age as an important factor for preoperative patient counselling and selection. However, other frailty assessments or surrogates might have yielded different results.

Conclusion

FESS is feasible and safe in elder patients with comorbidities with an overall low complication rate regarding emergency revision surgery and postoperative hospital readmission. However, multimorbidity should always elicit apprehension in an ambulatory setting as a relevant number of those patients require postoperative inpatient care. These results provide guidance regarding preoperative patient counselling. While patients with comorbidities can expect similar postoperative pain reduction following FESS, they might yield smaller functional benefits than their healthier and younger counterparts.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Heck, V. J. et al. Projections from surgical use models in Germany suggest a rising number of spinal fusions in patients 75 years and older will challenge healthcare systems worldwide. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 481(8), 1610–1619 (2023).

Walston, J. et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 54(6), 991–1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00745.x (2006).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56(3), M146–M157 (2001).

Rockwood, K. & Mitnitski, A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 62(7), 722–727 (2007).

Whitmore, R. G. et al. ASA grade and Charlson Comorbidity Index of spinal surgery patients: correlation with complications and societal costs. Spine J. 14(1), 31–38 (2014).

Minetos, P. D. et al. Discharge disposition and clinical outcomes after spine surgery. Am. J. Med. Qual. 37(2), 153–159 (2022).

Voskuijl, T., Hageman, M. & Ring, D. Higher Charlson Comorbidity Index scores are associated with readmission after orthopaedic surgery. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 472, 1638–1644 (2014).

Chan, V. et al. Frailty adversely affects outcomes of patients undergoing spine surgery: a systematic review. Spine J. 21(6), 988–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2021.01.028 (2021).

Baek, W., Park, S. Y. & Kim, Y. Impact of frailty on the outcomes of patients undergoing degenerative spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 23(1), 771. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04448-2 (2023).

Ali, R., Schwalb, J. M., Nerenz, D. R., Antoine, H. J. & Rubinfeld, I. Use of the modified frailty index to predict 30-day morbidity and mortality from spine surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 25(4), 537–541. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.10.SPINE14582 (2016).

Agarwal, N. et al. Impact of frailty on outcomes following spine surgery: a prospective cohort analysis of 668 patients. Neurosurgery 88(3), 552–557. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyaa468 (2021).

Flexman, A. M., Charest-Morin, R., Stobart, L., Street, J. & Ryerson, C. J. Frailty and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for degenerative spine disease. Spine J. 16(11), 1315–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2016.06.017 (2016).

Minetos, P. D. et al. Discharge disposition and clinical outcomes after spine surgery. Am. J. Med. Qual. 37(2), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JMQ.0000753240.14141.87 (2022).

Lee, M. J. et al. Risk factors for medical complication after spine surgery: a multivariate analysis of 1,591 patients. Spine J. 12(3), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2011.11.008 (2012).

Patel, A. A. et al. Minimally invasive versus open lumbar fusion: a comparison of blood loss, surgical complications, and hospital course. Iowa Orthop. J. 35, 130 (2015).

Hasan, S., Hartl, R. & Hofstetter, C. P. The benefit zone of full-endoscopic spine surgery. J. Spine Surg. 5(Suppl 1), S41–S56. https://doi.org/10.21037/jss.2019.04.19 (2019).

Ruetten, S., Komp, M., Merk, H. & Godolias, G. Full-endoscopic interlaminar and transforaminal lumbar discectomy versus conventional microsurgical technique: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Spine 33(9), 931–939. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816c8af7 (2008).

Gibson, J. N., Cowie, J. G. & Iprenburg, M. Transforaminal endoscopic spinal surgery: the future ‘gold standard’ for discectomy?—A review. Surgeon 10(5), 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2012.05.001 (2012).

Mahan, M. A. et al. Full-endoscopic spine surgery diminishes surgical site infections—a propensity score-matched analysis. Spine J. 23(5), 695–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2023.01.009 (2023).

Leyendecker, J. et al. Pain alleviation and functional improvement: ultra-early patient-reported outcome measures after full endoscopic spine surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 1, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3171/2023.11.SPINE231048 (2024).

Bajaj, A. I. et al. Comparative analysis of perioperative characteristics and early outcomes in transforaminal endoscopic lumbar diskectomy: general anesthesia versus conscious sedation. Eur. Spine J. 32(8), 2896–2902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07792-4 (2023).

Alexander, N. & Gardocki, R. Awake transforaminal endoscopic lumbar discectomy in an ambulatory surgery center: early clinical outcomes and complications of 100 patients. Eur. Spine J. 32(8), 2910–2917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07786-2 (2023).

Leyendecker, J. et al. Assessing the impact of obesity on full endoscopic spine surgery: surgical site infections, surgery durations, early complications, and short-term functional outcomes. J. Neurosurg. Spine 1, 1–6 (2023).

Bergquist, J. et al. Full-endoscopic technique mitigates obesity-related perioperative morbidity of minimally invasive lumbar decompression. Eur. Spine J. 32(8), 2748–2754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07705-5 (2023).

Rogozinski, J. et al. The utility of the Charlson Comorbidity Index and modified Frailty Index as quality indicators in total joint arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort review. Curr. Orthop. Pract. 31(6), 543–548 (2020).

Yao, M. et al. A systematic review of cross-cultural adaptation of the Oswestry disability index. Spine 41(24), E1470–E1478 (2016).

Khan, J. M. et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of patients with a lumbar far lateral herniated nucleus pulposus as compared to those with a central or paracentral herniation. Glob. Spine J. 9(5), 480–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568218800055 (2019).

Copay, A. G. et al. Minimum clinically important difference in lumbar spine surgery patients: a choice of methods using the Oswestry disability index, medical outcomes study questionnaire short form 36, and pain scales. Spine J. 8(6), 968–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2007.11.006 (2008).

Kamson, S., Trescot, A. M., Sampson, P. D. & Zhang, Y. Full-endoscopic assisted lumbar decompressive surgery performed in an outpatient, ambulatory facility: report of 5 years of complications and risk factors. Pain Phys. 20(2), E221–E231 (2017).

Kim, J. H. et al. Feasibility of full endoscopic spine surgery in patients over the age of 70 years with degenerative lumbar spine disease. Neurospine 15(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.1836046.023 (2018).

Kassicieh, A. J. et al. Endoscopic and nonendoscopic approaches to single-level lumbar spine decompression: propensity score-matched comparative analysis and frailty-driven predictive model. Neurospine 20(1), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2346110.055 (2023).

Adogwa, O. et al. 30-day readmission after spine surgery: an analysis of 1400 consecutive spine surgery patients. Spine 42(7), 520–524. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000001779 (2017).

Beauchamp-Chalifour, P. et al. The impact of frailty on patient-reported outcomes after elective thoracolumbar degenerative spine surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 1, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3171/2021.2.SPINE201879 (2021).

Stromqvist, F., Stromqvist, B., Jonsson, B. & Karlsson, M. K. Surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation in different ages-evaluation of 11,237 patients. Spine J. 17(11), 1577–1585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2017.03.013 (2017).

Parenteau, C. S., Lau, E. C., Campbell, I. C. & Courtney, A. Prevalence of spine degeneration diagnosis by type, age, gender, and obesity using Medicare data. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 5389. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84724-6 (2021).

Tran, K. S. et al. Modified frailty index does not provide additional value in predicting outcomes in patients undergoing elective transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. World Neurosurg. 170, e283–e291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.11.011 (2023).

Moses, Z. B. et al. The modified frailty index and patient outcomes following transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion surgery for single-level degenerative spine disease. J. Neurosurg. Spine 1, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.11.SPINE201263 (2021).

Hong, Y. G. et al. Association of frailty with regional sagittal spinal alignment in the elderly. J. Clin. Neurosci. 96, 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2021.10.008 (2022).

Langella, F. et al. The aging spine: the effect of vertebral fragility fracture on sagittal alignment. Arch. Osteoporos. 16(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-021-00975-w (2021).

Son, S., Yoo, B. R., Lee, S. G., Kim, W. K. & Jung, J. M. Full-endoscopic versus minimally invasive lumbar interbody fusion for lumbar degenerative diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 65(4), 539–548 (2022).

Nakajima, Y., Takaoki, K., Akahori, S., Motomura, A. & Ohara, Y. A review of fully endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion. J. Minim. Invas. Spine Surg. Tech. 8(2), 177–185 (2023).

Chen, Z., Luo, R., Yang, Y. & Xiang, Z. The prevalence of depression in degenerative spine disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Spine J. 30(12), 3417–3427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-021-06977-z (2021).

Sinikallio, S. et al. Depression is associated with poorer outcome of lumbar spinal stenosis surgery. Eur. Spine J. 16(7), 905–912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-007-0349-3 (2007).

Javeed, S. et al. Implications of preoperative depression for lumbar spine surgery outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 7(1), e2348565 (2024).

Sinikallio, S. et al. Depression is associated with a poorer outcome of lumbar spinal stenosis surgery: a two-year prospective follow-up study. Spine 36(8), 677–682 (2011).

Rahman, R. et al. Changes in patients’ depression and anxiety associated with changes in patient-reported outcomes after spine surgery. J. Neurosurg. Spine 32(6), 871–890 (2020).

Pochon, L., Kleinstuck, F. S., Porchet, F. & Mannion, A. F. Influence of gender on patient-oriented outcomes in spine surgery. Eur. Spine J. 25(1), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-015-4062-3 (2016).

Elsamadicy, A. A. et al. Impact of gender disparities on short-term and long-term patient reported outcomes and satisfaction measures after elective lumbar spine surgery: a single institutional study of 384 patients. World Neurosurg. 107, 952–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.082 (2017).

Kumar, N. et al. Gender disparities in postoperative outcomes following elective spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurosurg. Spine 1, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3171/2023.11.SPINE23979 (2023).

Pan, J., Yap, N., Prasse, T. & Hofstetter, C. P. Validation of smartphone app-based digital patient reported outcomes in full-endoscopic spine surgery. Eur. Spine J. 32(8), 2903–2909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-07819-w (2023).

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to extend thanks to the Endoscopic Spine Research Group (ESRG) of which Christoph P. Hofstetter is a member.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the analysis—C.H., I.K., J.L. Collected the data—M.K., V.S., L.R., P.R., I.M. Contributed data or analysis tools—J.L., T.P., P.R., J.B., P.E. Performed the analysis—J.L., I.K., I.M. Wrote the paper—J.L., I.K., I.M., C.H., J.B. Agreed the final version of the manuscript—All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leyendecker, J., Prasse, T., Rückels, P. et al. Full-endoscopic spine-surgery in the elderly and patients with comorbidities. Sci Rep 14, 29188 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80235-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80235-2