Abstract

Freezing of gait (FOG) in Parkinson’s disease (PD) can be triggered by sensomotor, cognitive or limbic factors. The limbic system’s impact on FOG is attributed to elevated limbic load, characterized by aversive stimuli, potentially depleting cognitive resources for movement control, resulting in FOG episodes. However, to date, PD patients with and without FOG have not shown alterations of anticipatory postural adjustments during gait initiation after exposure to emotional images, possibly because visual stimuli are less immediately disruptive than auditory stimuli, which can more directly affect attention and the limbic system. This study aims to determine if step initiation is influenced by ecological auditory stimuli with emotional content in patients with FOG compared to those without. Forty-five participants, divided into 3 groups (15 PD with FOG, 15 PD without FOG in ON state, and 15 healthy subjects), stood on a force platform and were asked to step forward in response to neutral, pleasant, or unpleasant ecological auditory stimuli. Anticipatory postural adjustments were investigated in imbalance and unloading phases, while spatio-temporal parameters, including center of pressure (CoP) displacements, were computed for step initiation. PD with FOG showed a reduction of CoP displacements after listening to unpleasant stimuli. Conversely, pleasant stimuli facilitated CoP displacements in these subjects. No influence of affective stimuli on CoP displacements was found in the other two groups. Multiple regression analysis revealed that the behavioral pattern in PD with FOG, modulated by stimuli with affective valence, was mainly associated with the limbic area (i.e., depression). The findings showed that the emotional network plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of freezing, generating probably interference with attentional reserves that trigger FOG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Freezing of Gait (FOG), defined as “a brief, episodic absence or marked reduction of forward progression of the feet despite the intention to walk”1, is one of the most disabling symptoms that severely affects gait, increases the risk of falls, and impacts independence in daily life activities of individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD)1.

Anticipatory postural adjustments (APAs) are crucial movements that occur before gait initiation to stabilize the body and prepare for stepping2,3,4. In individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD), these movements are often impaired, leading to difficulties in balance and gait initiation. Specifically, patients with PD may exhibit delayed and/or reduced APAs, resulting in instability or hesitations, particularly in those experiencing FOG. APAs during gait initiation are commonly measured by analyzing the displacement of the center of pressure (COP), which reflects the body’s preparatory postural adjustments prior to stepping5. During gait initiation, APAs can be divided into two phases: (1) the imbalance phase, which occurs from the onset of movement to the heel-off of the leading foot. During this phase, the COP shifts posteriorly and laterally towards the stance limb to create the necessary instability for forward stepping, and (2) the unloading phase, which spans from the end of the imbalance phase to the toe-off of the leading foot. Here, the COP moves anteriorly and medially, facilitating the transfer of body weight onto the leading foot4.

The APAs alterations contribute to an increased risk of falls and further mobility limitations in PD, therefore, understanding and addressing APAs in PD is a key point to improve functional mobility and reduce fall risks in these individuals.

Although FOG is a paroxysmal phenomenon triggered by several environmental factors (e.g., doorway, crosswalk), it is known to be exacerbated by stressors or emotional circumstances6, including fearful or anxious scenarios7,8,9,10. Recent imaging studies11,12,13 have confirmed the potential involvement of the limbic Basal Ganglia (BG) circuit in FOG pathophysiology. Results showed increased striato-limbic connectivity, abnormal attentional fronto-parietal network control over the amygdala11, and weakened interaction within the motor network and between the cognitive control network and the striatum12.

We previously investigated how emotional visual stimuli influence step initiation in PD participants with and without FOG9. Results revealed that unpleasant images modulated the spatio-temporal parameters of step initiation in freezers. However, no significant changes were observed in the APAs of individuals with FOG. This finding was unexpected, as previous research has shown that PD subjects with FOG exhibit reduced APAs during gait initiation compared to PD individuals without freezing14.

The “cross-talk” model11 proposes that a transient overload of the BG in processing competing cognitive, sensorimotor, and emotional inputs may be responsible for FOG. Specifically, it suggests that an overload of limbic demands during motor tasks could contribute to a transient increase in the inhibitory output of the BG15,16, resulting in the reduction of activity in the brainstem centers (e.g., pedunculopontine nucleus) which coordinate gait17. According to this model, we would expect hypometric APAs, which should get worse when gait initiation is triggered by emotional stimuli. However, a significant difference in the APAs displacements between PD individuals with and without FOG and healthy subjects9 was not found. The type of stimulus used in the experiments (i.e., visual) may have contributed to the lack of emotional influence on APAs9. Since the use of auditory stimuli allows for quicker access to the brain cortex compared to visual stimuli18, it is preferable to use auditory stimuli in experiments involving reaction to an external cue, where subjects respond to a start signal by performing a single motor task as quickly and accurately as possible. This approach helps to avoid potential confounding environmental factors and longer processing times. Additionally, research has shown that emotionally salient nonverbal vocalizations can activate the amygdala regardless of the subject’s attentional state14,15,16, suggesting that humans may be sensitive to emotionally significant background auditory stimuli. A recent review further underscores the consistent and positive impact of auditory cues on gait kinematics, particularly beneficial for individuals with PD19.

Rhythmic auditory stimuli, like metronomes or music with a regular beat, have been proven to improve gait, reduce FOG and risk of falls in individuals with PD by synchronizing movements and enhancing motor performance20,21,22. However, in everyday life, people, including individuals with PD, encounter a wide range of emotionally charged auditory stimuli (e.g., laughter, screams, yawns), which can trigger rapid responses essential for well-being and survival.

This was recently supported by a study examining the influence of emotion-based auditory stimuli on group synchronization performance in healthy individuals23. The findings indicated that the quality and speed of performance varied based on the emotional valence of the stimuli, affecting the motor responses of participants at both individual and group levels. Negative emotional inductions, in particular, led to decreased performance, highlighting the interplay between emotional states and joint action dynamics.

Individuals with Parkinson’s disease often experience altered emotional responses due to dysfunction in dopaminergic and limbic circuits, which can impact motor reactions. Integrating standardized emotional auditory stimuli into experimental designs aimed at assessing motor performance can effectively investigate how emotions influence these reactions. This methodology could provide crucial insights into emotional processing in patients with PD. Consequently, findings from studies that replicate real-world stimuli are needed and could provide useful tools to optimize motor performance by reducing confounding variables and creating more effective rehabilitation therapies that address both motor and non-motor deficits associated with gait alterations. This approach bridges the gap between controlled laboratory assessments and real-world scenarios, enhancing the ecological validity of research findings and promoting their translational impact14,16,17,18,19. For the above reasons, the present study was designed to specifically test whether emotional auditory inputs would impact step initiation, and in particular the feedforward control, in PD subjects with FOG. We hypothesized that APAs, in response to emotional auditory stimuli, would be more affected in freezers compared to PD individuals without FOG and healthy controls.

Results

All participants successfully and autonomously completed the task without experiencing any episodes of FOG.

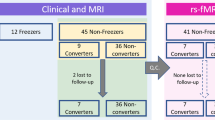

The three groups were matched for gender (p = 0.35) and education (p = 0.24). However, PD-FOG participants were found to be older compared to both the PD (p = 0.012) and the Healthy Control Group (HC) (p < 0.001).

In PD groups, some clinical symptoms were significantly more severe in PD-FOG compared to PD participants. These included disease duration (p = 0.020), H&Y stage (p = 0.001), and severity in MDS-UPDRS part III scores (p = 0.011). Additionally, mobility and balance performance were significantly worse in PD-FOG compared to PD participants (SPPB p = 0.004; MDGI p < 0.001 and number of falls p = 0.01).

No significant differences were found between PD and PD-FOG participants in terms of cognition, as measured by MoCA scores (p = 0.27) and the FAB scores (p = 0.06), and in mood status (BDI part II p = 0.052). However, anxiety levels, assessed with BAI scale, were slightly higher in the PD-FOG group (p = 0.047). Details are reported in Table 1.

Regarding the Self-Assessment Manikin scores of PD subjects, valence and arousal ratings were analyzed using a Valence x GROUP (PD vs. PD-FOG) ANOVA.

The ANOVAs performed on the valence and arousal ratings revealed a main effect of emotional valence (F(2, 56), p < 0.001; F(3, 56), p < 0.001, respectively), with no differences between groups (p = 0.23 and p = 0.83, respectively). Post hoc analysis revealed significant differences in the valence ratings (p < 0.001) among the three emotional categories of stimuli (mean valence rating (95% CI): pleasant stimuli: 6.30 (5.94–6.66), unpleasant stimuli 2.82 (2.30–3.34), and neutral stimuli 4.70 (4.35–5.04). For the arousal ratings, pleasant stimuli showed higher scores than both unpleasant (P = 0.007) and neutral stimuli (P < 0.001): pleasant stimuli: 6.05 (5.54–6.55), unpleasant stimuli 5.10 (4.41–5.80), and neutral stimuli 4.89 (4.44–5.34).

CoP displacements

Figure 1 illustrates the setup used to quantify APAs during gait initiation (a) by measuring the displacement of the COP on force platforms during the imbalance and unloading phases (b).

Statistical analysis of the imbalance phase showed a significant effect of GROUP for both CoPAP (F(2,41) = 3.9 p = 0.03) and CoPML (F(2,41) = 8.6, p < 0.001) displacements. Post-hoc analysis revealed that the posterior shift in the CoPAP was reduced in PD-FOG compared to HC (PB=0.002), while both PD (PB=0.005), and PD-FOG (PB=0.020) exhibited significantly decreased CoPML displacement compared to HC (Fig. 2A1; Table 2). Furthermore, a significant GROUP x STIMULI interaction was found for both CoPAP (F(6,123) = 4.56 p < 0.001) and CoPML (F(6,123) = 7.07 p < 0.01) displacements (Table 2) (Table 3).

Center of Pressure (COP) displacements during emotional gait initiation task for the imbalance (Panels A, B) and unloading (Panels C, D) phases. COP data [Median values and IQR] are reported on Y axes. Group values are shown in the left panel (1), and the experimental conditions (B, N, P, U) are displayed in the remaining panels on the X-axes (HC: (2), PD: (3), PD-FOG: (4)). HC healthy control, PD Parkinson’s Disease, FOG freezing of gait, AP antero-posterior, ML medio-lateral. Asterisks indicate significant difference (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Specifically, for CoPAP, post-hoc analysis revealed that the posterior shift in PD-FOG was reduced with respect to HC in response to the unpleasant stimuli (PB=0.047, Fig. 2, panel A4). In addition, in PD-FOG the posterior shift was smaller after listening to unpleasant stimuli compared to the neutral stimulus (PB=0.013, Fig. 2 panel A4) and it was significantly increased after listening to pleasant stimuli compared to baseline condition (p = 0.001, Fig. 2 panel A4). Moreover, a significant difference between the response after pleasant and unpleasant stimuli (p < 0.0001) was also detected (Fig. 2, panel A4 and Fig. 3 panel A).

The graphs show the differential behavior of the Center Of Pressure (COP) displacements during gait initiation task in response to unpleasant and pleasant, and for each group. AP (Panels A, C) and ML (Panels B, D). CoP displacements [Median values and IQR] are reported on Y axes. FOG freezing of gait, AP antero-posterior, ML medio-lateral. Asterisks indicate significant difference (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

For CoPML, post-hoc analysis revealed that PD-FOG had smaller displacement with respect to HC in response to unpleasant stimuli (PB=0.045, Fig. 2 panel B4). Additionally, PD-FOG showed reduced CoPML displacements after listening to unpleasant stimuli compared to the baseline (PB=0.045) and neutral (PB=0.003) conditions (Fig. 2, panel B4). Also, CoPML displacements were significantly increased in response to pleasant stimuli compared to the baseline (PB<0.002) neutral (PB<0.034) conditions (Fig. 2, panel B4). Lastly, a significant difference was observed between the response after pleasant and unpleasant stimuli (PB<0.001, Fig. 2, panel B4, P < 0.001 Fig. 3, panel B).

Regarding the unloading phase, results for CoPAP displacement showed a significant effect of GROUP (F(2,41), p = 0.03, Table 2), without significant difference between groups (Table 2). No differences either for valence or CoPML data were found (Table 2; Fig. 2 panels C,D, Fig. 2 panels C1–C3 and D1–D3, Fig. 3 panels A–D).

Timing and kinematic parameters

A complete overview of these results is provided in Table S1. The RT values were comparable among groups (F(2,41) = 1.29, p = 0.29) and emotional stimuli (F(3,123) = 0.50, p = 0.68), and no significant interactions (F(6,123) = 1.25, p = 0.28) were found. Similarly, step length and velocity were comparable among groups and emotional valences (p always > 0.05).

However, a significant effect of GROUP (F(2,41) = 04.78, p = 0.01) was found for duration of the first step (TSTEP). Post-hoc analyses revealed that both PD and PD-FOG took a longer time to complete the step compared to HC (PD: PB<0.011; PD-FOG: PB=0.029 Table S1).

Also, a significant main effect of GROUP was found (F(2,41) = 6.64 p = 0.02 and F(2,41) = 3.92 p = 0.03) for the duration of imbalance and unloading phases. Post-hoc tests showed that in PD both TIMB and TUNL were longer than in the HC (PB=0.036 and 0.043), whereas in PD-FOG only the TUNL was greater than in the HC (PB=0.014).

Multiple linear regression

The resulting multiple linear regression models are displayed in Table S2. Psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, were predictors in all models. Specifically, during the imbalance phase, depression (BDI) was the only predictor of differential behavior in the anterior-posterior direction (Fig. 3 panels A,B), while global cognition (measured by MoCA and FAB) and motor ability (assessed by mDGI) were predictors in the mediolateral direction. During the unloading phase (Fig. 3C,D), anxiety (measured by BAI) was a significant predictor in both directions, whereas motor ability (assessed by mDGI) was a significant predictor only in the medio-lateral direction.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the effect of emotional auditory stimuli on step initiation in persons with PD who experience freezing of gait. We compared behavioral data from a cohort of PD participants with or without FOG and a control group of healthy subjects. Although PD subgroups differed in terms of age, disease duration and severity, which are features strongly correlated, the results of the present study are not dependent on these confounding factors. Age was indeed used as a covariate, as it accounts for aging and disease status, and therefore the differences found are really attributable to different pathophysiological factors among subjects with or without FOG. From the perspective of affective valence (P, N, U), all auditory stimuli were categorized as expected from PD subjects with or without FOG, while from the perspective of arousal, the stimuli were on the same level.

To simulate real-life circumstances, where emotional stimuli may influence gait patterns, unpleasant and pleasant ecological auditory stimuli were used. The main finding of our study was that emotional stimuli affect automatic movement parameters during the imbalance phase of gait initiation, specifically in individuals with PD who experience FOG. Interestingly, no similar changes were observed in persons with PD without FOG or in healthy control subjects. This finding underscores the potential interplay between emotional factors and motor symptoms, particularly in persons with PD suffering from FOG episodes.

The experimental protocol of this study was designed based on theories that emotions influence movement through automatic, unintentional mechanisms, known as avoidance-approach behaviors24,25. Based on this assumption, we expected that automatic movements preceding step initiation would be modulated in accordance with the emotional valence of the stimuli, across all groups, as observed in our previous work where emotional visual stimuli were applied9. Contrary to our expectations, we found that emotion-induced changes in APAs were only evident in individuals experiencing FOG during the imbalance phase of gait initiation, compared to HC and PD without FOG.

In this study, the lack of the emotional stimuli influence on APAs in healthy subjects and PD without FOG could be ascribed to the specific type of emotional stimuli employed. The easily categorizable real-life sounds (e.g., rain, neutral; laughing, pleasant; scream, unpleasant) may have facilitated proper reactions to emotional stimuli in HC and PD as they started walking. On the other hand, during the imbalance phase, freezers showed a significant reduction of automatic movements (APAs) compared to HC and PD without FOG while listening to unpleasant sounds.

As proposed by recent evidence6,24, this result may be related to the disrupted interaction among BG networks, including motor, cognitive, and emotional circuits, which are known to be involved in FOG pathophysiology. Notably, the execution of a forward step in response to unpleasant stimuli represents an incongruent task (i.e., approach toward unpleasant stimuli) requiring a higher cognitive load (i.e., less automatic responses) compared to a congruent task (i.e., approach toward pleasant stimuli), which is facilitated by automatic reactions. This strategy can be employed following exposure to various types of stimuli, including auditory stimuli that can amplify these effects, as it creates a more immediate sense of directionality. In fact, recent studies have shown that, among various types of stimuli, sound stimuli have proven to be the most effective for recalibrating spatial orientation in immersive reality environments25.

Thus, it might be possible that altered postural responses were triggered in freezers when competing motor, cognitive, and limbic inputs overload the basal ganglia26. Moreover, the negative valence of unpleasant stimuli may heighten the sense of the postural threat experienced,26 thereby activating defensive strategies that induce an automatic immobility reaction, as previously observed in animals and humans when facing a threat27. In a previous work, we demonstrated that the incongruent task proved most challenging for freezers, resulting in a motor response inhibition manifested as longer reaction times and shorter step lengths9. However, it is important to note that the differences in the CoP displacements according to the affective valence (Fig. 3), observed in subjects with FOG, were not found when visual stimuli were applied9. This discrepancy could be attributed to the different nature of the stimuli involved5. Even though APA is an automatic movement, it is governed by various structures within the brain. Specifically, imbalance processes are mainly regulated by cortical and subcortical structures (i.e., supplementary motor area, premotor cortex, BG), while the unloading processes are generally regulated by lower-level control mechanisms (i.e., brainstem and spinal processes)28,29. In motor tasks, even under physiological conditions, visual reaction times are slower compared to auditory reaction times30. The quicker a stimulus reaches the brain, the faster it can be processed, enabling more rapid motor responses. Consequently, visual stimuli may exert less influence on movements characterized by short durations, such as gait initiation.

Regarding the unloading phase, our results didn’t show a significant effect of emotional stimuli on the body-weight shift from the leading leg to the trailing leg in all three groups (HC, PD, PD-FOG). However, we found a distinct biomechanical strategy in individuals with PD without FOG, characterized by a forward placement of the CoP, closer to the toes, at the onset of the unloading phase. Body weight shift during gait is primarily regulated by the proprioceptive feedback, which relies on the detection of kinematic characteristics such as joint position, muscle activation timing, and strength. This proprioceptive feedback process is known to be impaired in PD31. It has been reported that individuals with PD without FOG exhibit difficulties with sensory integration and poorer automatic postural control (e.g., delayed activation of ankle, thigh, and trunk muscles) at the ankle or hip level compared to individuals with FOG31. This could potentially explain the distinct biomechanical strategy observed in individuals with PD without FOG.

No significant main effect of group and emotional stimuli was observed during the unloading phase (Fig. 2, panels C,D). This could be related to a better compensatory ability during the unloading phase in patients with PD32, due to the greater effect of dopamine on the basal ganglia. Dopamine facilitates the correct selection of motor synergies in automatic responses, such as the body weight shift that occurs in this phase and does not require cognitive processing28,29,33.

Finally, our study investigated whether motor, cognitive, or affective disturbances may have influenced the automatic movements preceding step initiation. The results of our regression model revealed that the behavioral pattern of the COP with an emotional-opposite valence-based trend, especially in PD-FOG, (reduced and increased in response to unpleasant and pleasant stimuli, respectively) was primarily associated with the emotional-mood domain, as anxiety or depression were present in the four modeled COP parameters. These associations align with current understanding of the neural networks that control the APA phases and the non-motor symptoms that may contribute to the development of FOG28,29,34. Among the non-motor contributors to FOG (i.e. cognition sensory-perceptual and affective), studies have consistently shown the role of affective domains, such as anxiety and depression, as longitudinal predictors for the future development of FOG in PD patients34. Therefore, considering the association between valence-based (pleasant/unpleasant) CoP shifts and depression, the affective valence-based APA measures could serve as potential biomarker of FOG, since the response (COP shift) in freezers after listening to pleasant and unpleasant stimuli was opposite: pleasant stimuli appeared to facilitate movement, while unpleasant stimuli seemed to inhibit it. This behavior was not observed in non-freezers, but only in freezers, which suggests it could be used for monitoring the FOG development and for measuring physiotherapy-induced changes on freezing severity and symptoms. Indeed, FOG remains, so far, a critical issue in PD, since various circumstances, including motor tasks (e.g., turning), cognitive tasks (e.g., dual-tasking), and environmental challenges (e.g., negotiating doorways) or anxiety-inducing contexts, can trigger FOG during walking35 with great inter-individual variability. However, despite its negative consequences and prevalence, FOG lacks effective treatment options and shows limited response to conventional therapies for PD, such as dopamine replacement or deep brain stimulation. Thus, there is necessity to investigate additional therapies targeting FOG reduction. Our findings suggest that introducing a multidimensional strategy, integrating the limbic domain into training, holds promise for alleviating FOG. Our results and the recommendations stemming from them align with recent findings outlined in a review36, which underscore the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in mitigating anxiety and depression—both potential triggers and risk factors for freezing episodes37,38,39. Therefore, motor and behavioral cognitive interventions could be valuable tools for reducing FOG symptoms and severity.

Limitations and conclusions

Some limitations related to the experimental protocol deserve to be discussed. First, our patients were tested in the ON state, where motor symptoms are typically improved. While this approach allowed us to examine the influence of emotional processing on gait initiation under more ecologically valid conditions, it may not fully capture the factors that contribute to FOG during gait initiation in the medication-off state.

Second, the sample size of this cross-sectional study might have resulted in limited generalization. Thus, this study should be considered as an explorative study, albeit those previous publications related to APA assessment in PD used comparable group size populations4,9,31. However, an a-posteriori power analysis found a large effect size of the COPAP_IMB after listening unpleasant stimuli between PD-FOG versus HC (effect size d = 2.34) and PD (effect size d = 1.25). These large effect sizes values suggest these relationships are quite robust and that there was sufficient power (fixed α = 0.05, β > 0.90) to accurately detect the effects of interest with our sample sizes. Nevertheless, further studies with larger and more diverse samples are needed to validate and extend our findings to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between emotions and freezing of gait in PD.

Materials and methods

Participants

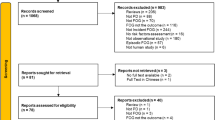

Thirty subjects with PD, 15 without FOG (11 male; age, [median (1st − 3rd )]: 70.0 (66.0–75.0) years) and 15 with FOG (10 male; age, [median (1st − 3rd )]: 73.0 (71.0–82.0) years), were recruited at IRCCS Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi (Milan). PD participants were classified as freezer (PD-FOG) based on subjective experience of FOG (NFOG-Q_IT item1 = 117) or after clinical observation during the recruitment phase. Inclusion criteria were: (i) diagnosis of idiopathic PD (according to the United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank criteria40), (2) Hoehn & Yahr stage between 2 and 3, (3) Mini-Mental State Examination ≥ 24, (4) able to walk unassisted for at least 6 min. Exclusion criteria were: (1) deep brain stimulation implant, (2) history of neurologic disorders (except PD), (3) visual, orthopedic, or other health conditions that could hamper task performance, (4) need of hearing aids, (5) any other physiotherapy training 1 month before participation.

Severity of motor symptoms was evaluated with the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) part III. Mobility was assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), and the modified Dynamic Gait Index (mDGI) was used to evaluate balance. Freezing characteristics were evaluate using the Characterizing Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (C-FOG)41. Global cognition and executive functions were assessed by means of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and of the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) respectively. The affective status was evaluated using the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI II) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). All PD participants were under treatment with dopaminergic therapy, and the experiment took place during the “ON” medication state. Clinical characteristics of PD participants are reported in Table 1.

Fifteen healthy control (HC) subjects (7 male; age, [median (1st − 3rd )]: 68.0 (65.0–71.0) years; Education, [median (1st − 3rd )]: 8 (8.0–17.0) years), without any history of neurological disorders, or severe musculoskeletal impairments, were recruited to collect normative data for the measurement of the APAs and step initiation characteristics. All participants gave their written informed consent to the study that was approved by the ethical committee of IRCCS Don Carlo Gnocchi Foundation, Milan, Italy (session October 16, 2019). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental paradigm

Participants attended our laboratories for a one-day evaluation consisting of the clinical assessments and the emotional gait initiation task. During the experimental task, participants were asked to stand still with a self-selected stance width, placing both feet on one force platform, and to initiate gait in response to auditory stimuli (Fig. 1, panel A). The instruction was always to take a step forward immediately upon hearing the stimulus through Bluetooth headphones and to stop as soon as possible with both feet on the ground. The experimental protocol always began with the baseline condition, followed by the random presentation of auditory-emotional stimuli (see below for details).

The optoelectronic system with 10 cameras (BTS, Smart DX) was used to record the coordinates of 9 retro-reflective markers: 4 for each foot (heel, first toe, 5th metatarsal head and lateral malleolus) and one for the pelvis. Two force plates (BTS, P-6000) provided ground reaction forces (GRFs).

A custom-made software, developed in the Visual Studio (Microsoft, USA) environment, was used to control the trial onset and offset, the auditory stimulus presentation and the synchronization with the optoelectronic system, including the GRFs. Additionally, for every stimulus sent to the headphones, a synchronous trigger signal was dispatched to SMART Capture software (BTS).

Emotional stimuli

During the experimental task, auditory stimuli were used to induce emotional states. Fifteen digitized sounds were selected from the International Affective Digitized Sounds (IADS-2)42 database. For each affective category, specifically unpleasant, neutral, and pleasant, five ecologically relevant auditory stimuli were chosen based on their ratings on the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) scale of pleasure43. Unpleasant stimuli (e.g., attack, ambulance siren, car wreck, scream, buzzer) had SAM values ranging from 1 to 3, neutral stimuli (e.g., newspaper, writing, brushing teeth, rain) had values between 4 and 6, and pleasant stimuli (e.g., laughing, brook, beer, applause, happy crowd) had values > 6. The order of presentation of the emotional stimuli was randomized to avoid any systematic bias. Five catch trials were included in the experiment, where a neutral voice saying ‘Go’ was used as the stimulus (i.e., baseline condition).

At the conclusion of the experimental session, the emotional auditory stimuli were replayed to the subjects with Parkinson’s disease in a randomized sequence. The SAM was used to obtain subjective ratings of valence and arousal for stimuli presented during the experiment.

Step initiation metrics

The temporal instants of the APA onset (i.e. the Toe-Off of the trailing limb (TOtr) and of the leading limb (TOld), the Heel-Off and the Heel-Strike of the leading limb (HOld, HSld)) were automatically extracted by means of ad hoc Matlab (MathWorks, USA) algorithms according to Crenna et al.4 These instants were crucial for identifying two phases: the imbalance phase, characterized by a backward shifttoward the leading limb (swing foot), and the unloading phase, marked by lateral movement of the CoP toward the trailing limb (stance foot) (Fig. 1, panel B).

Once the temporal instants were determined, the following set of parameters were measured:4.

-

Reaction Time (RT): latency between the movement trigger (stimulus release) and the initiation of the motor response (APAonset).

-

Duration of imbalance phase (TIMB): duration time from the instant of APA onset to the instant of Heel-Off leading foot (HOld; the foot which performs the first step) and.

-

Duration of unloading phase (TUNL): duration time from the instant of HOld to the instant of Toe-Off of the leading foot (TOld) and.

-

Duration of step (TSTEP): duration time from the instant of HOld and tothe instant of the Heel-strike of the leading foot (HSld) .

-

Step Length (LSTEP): displacement of the lateral malleolar marker trace from HOld to HSld.

-

CoP movement during imbalance phase (CoPIMB): displacements of the CoP trace in both the medio-lateral (CoPIMB_ML) and anterior–posterior (CoPIMB_AP) directions normalized to the distance between lateral malleolar and fifth metatarsal marker.

-

CoP Displacement during unloading phase (CoPUNL): displacements of the CoP trace in both the medio-lateral (CoPUNL_ML) and anterior–posterior (CoPUNL_AP) directions normalized to the inter-malleolar distance during standing.

Statistical analysis

The normality of data distribution and homogeneity of variances were assessed by Shapiro–Wilk and Levene test, respectively. The chi-squared (χ2) test was used to compare sex distribution among the groups (HC, PD, and PD-FOG). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed for age, education, and anthropometric data. Differences in the clinical scales between PD and PD-FOG were assessed using unpaired t-test (MDS-UPDRS part III, mDGI, BDI-II, MoCA), or Mann-Whitney test (fall number, disease duration, BAI, SPPB, FAB).

Instrumental parameters were analyzed with a 3 × 4 RM-ANOVA with GROUP (PD-FOG, PD, HC) as the between-factor, and STIMULI (Baseline (B), Neutral (N), Pleasant(P), Unpleasant (U)) as the within-factor. Age was included as a covariate in the analysis. Post-hoc analysis was used to determine statistically significant differences among the groups and/or valences. In particular, P values were corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni procedure (PB).

To determine the best model to predict behavioral response of the opposite valence, pleasant and unpleasant, multiple linear regression models were derived for each parameter of the difference in CoP displacement after pleasant and unpleasant stimuli (COP_unpleasant - COP_pleasant). Clinical scales (MDS-UPDRS III, mDGI, SPPB, MoCA, FAB, BDI II and BAI) were used as independent variables. The multiple linear regression model selection followed a backward elimination process. First, variance inflation factors (VIF) were computed to check for potential multicollinearity. If the VIF (variance inflation factors) exceeded 5, the independent variables were screened for correlations and removed from the model. The least significant independent variable was then removed iteratively until only significant variables remained25. The normality and homogeneity of variances of the regression model residuals were assessed using the Shapiro–Wilks test and White’s test, respectively.

The data processing and the statistical analysis were conducted using Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Giladi, N. & Nieuwboer, A. Understanding and treating freezing of gait in parkinsonism, proposed working definition, and setting the stage. Mov. Disord. 23 (Suppl 2), S423–S425 (2008).

Bonora, G. et al. Gait initiation is impaired in subjects with Parkinson’s disease in the OFF state: evidence from the analysis of the anticipatory postural adjustments through wearable inertial sensors. Gait Posture 51, 218–221 (2017).

Crenna, P. & Frigo, C. A motor programme for the initiation of forward-oriented movements in humans. J. Physiol. 437, 635–653 (1991).

Crenna, P. et al. Impact of subthalamic nucleus stimulation on the initiation of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Brain Res. 172, 519–532 (2006).

Jacobs, J. V., Horak, F. B. & Horak, F. B. Cortical control of postural responses HHS public access. J. Neural Transm. 114, 1339–1348 (2007).

Avanzino, L., Lagravinese, G., Abbruzzese, G. & Pelosin, E. Relationships between gait and emotion in Parkinson’s disease: a narrative review. Gait Posture 65, 57–64 (2018).

Misslin, R. The defense system of fear: behavior and neurocircuitry. Neurophysiol. Clin. 33, 55–66 (2003).

Blanchard, D. C., Griebel, G., Pobbe, R. & Blanchard, R. J. Risk assessment as an evolved threat detection and analysis process. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 991–998 (2011).

Lagravinese, G. et al. Gait initiation is influenced by emotion processing in Parkinson’s disease patients with freezing. Mov. Disord. 33, 609–617 (2018).

Quek, D. Y. L., Economou, K., MacDougall, H. & Lewis, S. J. G. Ehgoetz Martens, K. A. validating a seated virtual reality threat paradigm for inducing anxiety and freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 11, 1443–1454 (2021).

Gilat, M. et al. Dysfunctional limbic circuitry underlying freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience 374, 119–132 (2018).

Ehgoetz Martens, K. A. et al. The functional network signature of heterogeneity in freezing of gait. Brain 141, 1145–1160 (2018).

Sarasso, E. et al. Brain activity of the emotional circuit in Parkinson’s disease patients with freezing of gait. Neuroimage Clin. 30, 102649 (2021).

Schlenstedt, C. et al. Are hypometric anticipatory postural adjustments contributing to freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease? Front. Aging Neurosci. 10, 36 (2018).

Lewis, S. J. G. & Barker, R. A. A pathophysiological model of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15, 333–338 (2009).

Nieuwboer, A. & Giladi, N. Characterizing freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: models of an episodic phenomenon. Mov. Disord. 28, 1509–1519 (2013).

Lewis, S. J. G. & Shine, J. M. The next step: a common neural mechanism for freezing of gait. Neuroscientist 22, 72–82 (2016).

Shelton, J. & Kumar, G. P. Comparison between auditory and visual simple reaction times. Neurosci. Med. 1, 30–32 (2010).

Trindade, M. F. D. & Viana, R. A. Effects of auditory or visual stimuli on gait in Parkinsonic patients: a systematic review. Porto Biomed. J. 6, e140 (2021).

Ginis, P., Nackaerts, E., Nieuwboer, A. & Heremans, E. Cueing for people with Parkinson’s disease with freezing of gait: a narrative review of the state-of-the-art and novel perspectives. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 61, 407–413 (2018).

Thaut, M. H., Rice, R. R., Janzen, B., Hurt-Thaut, T., McIntosh, G. C. & C. P. & Rhythmic auditory stimulation for reduction of falls in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled study. Clin. Rehabil. 33, 34–43 (2019).

Schaffert, N., Janzen, T. B., Mattes, K. & Thaut, M. H. A review on the relationship between sound and movement in sports and rehabilitation. Front. Psychol. 10, 412985 (2019).

Bieńkiewicz, M. M. N., Janaqi, S., Jean, P. & Bardy, B. G. Impact of emotion-laden acoustic stimuli on group synchronisation performance. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–15 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Aberrant advanced cognitive and attention-related brain networks in Parkinson’s disease with freezing of gait. Neural Plast. 2020 181–184. (2020).

Lee, J., Hwang, S., Kim, K. & Kim, S. J. Evaluation of visual, auditory, and olfactory stimulus-based attractors for intermittent reorientation in virtual reality locomotion. Virtual Real 28, 1–18 (2024).

Adkin, A. L., Frank, J. S., Carpenter, M. G. & Peysar, G. W. Postural control is scaled to level of postural threat. Gait Posture 12, 87–93 (2000).

Kozlowska, K., Walker, P., McLean, L. & Carrive, P. Fear and the defense cascade: clinical implications and management. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 23, 263–287 (2015).

Rocchi, L., Chiari, L., Cappello, A. & Horak, F. B. Identification of distinct characteristics of postural sway in Parkinson’s disease: a feature selection procedure based on principal component analysis. Neurosci. Lett. 394, 140–145 (2006).

Takakusaki, K., Habaguchi, T., Ohtinata-Sugimoto, J., Saitoh, K. & Sakamoto, T. Basal ganglia efferents to the brainstem centers controlling postural muscle tone and locomotion: a new concept for understanding motor disorders in basal ganglia dysfunction. Neuroscience 119, 293–308 (2003).

Jain, A., Bansal, R., Kumar, A. & Singh, K. A comparative study of visual and auditory reaction times on the basis of gender and physical activity levels of medical first year students. Int. J. Appl. Basic. Med. Res. 5, 124 (2015).

Vervoort, G. et al. Which aspects of postural control differentiate between patients with parkinson’s disease with and without freezing of gait? Parkinsons Dis. 971480 (2013).

Palmisano, C. et al. Gait initiation in Parkinson’s disease: impact of dopamine depletion and initial stance Condition. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 137 (2020).

Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. Affective reactions to acoustic stimuli. Psychophysiology 37, 204–215 (2000).

Ehgoetz Martens, K. A. et al. Behavioural manifestations and associated non-motor features of freezing of gait: a narrative review and theoretical framework. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 116, 350–364 (2020).

Gilat, M. et al. A systematic review on exercise and training-based interventions for freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 7, 81 (2021).

Chow, R., Tripp, B. P., Rzondzinski, D. & Almeida, Q. J. Investigating therapies for freezing of gait targeting the cognitive, limbic, and sensorimotor domains. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 35, 290 (2021).

Ehgoetz Martens, K. A., Ellard, C. G. & Almeida, Q. J. Anxiety-provoked gait changes are selectively dopa-responsive in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 42, 2028–2035 (2015).

Gao, C., Liu, J., Tan, Y. & Chen, S. Freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: pathophysiology, risk factors and treatments. Transl. Neurodegener. 9, 1–22 (2020).

Gilat, M. et al. A systematic review on exercise and training-based interventions for freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinson’s Dis. 7, 1–18 (2021).

Hughes, A. J., Daniel, S. E., Kilford, L. & Lees, A. J. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 55, 181–184 (1992).

Ehgoetz Martens, K. A. et al. Evidence for subtypes of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 33, 1174–1178 (2018).

Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. International Affective Digitized Sounds (2nd Edition; IADS-2): Affective ratings of sounds and instruction manual (Technical Report No. B-3). Gainesville, FL: University of Florida, NIMH Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention. (2007a).

Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 25, 49–59 (1994).

Acknowledgements

This research was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Corrente. LA, EP and MP are supported by #NEXTGENERATIONEU (NGEU) and funded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR), National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), project MNESYS (PE0000006) – A Multiscale integrated approach to the study of the nervous system in health and disease (DN. 1553 11.10.2022). GB is supported by #NEXTGENERATIONEU (NGEU) and by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR), National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.5, project “RAISE - Robotics and AI for Socio-economic Empowerment” (ECS00000035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TL, design, execution, analysis, data interpretation, writing, editing of final version of the manuscript. IC, VG, analysis, data interpretation, writing. MM, TB, participants recruiting and execution. SM, CC, GB, MP, MF, design, and data interpretation. LA, writing and editing of final version of the manuscript. EP, design, analysis, writing, editing of final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lencioni, T., Meloni, M., Bowman, T. et al. Emotional auditory stimuli influence step initiation in Parkinson’s disease with freezing of gait. Sci Rep 14, 29176 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80251-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80251-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Motor planning stage of gait initiation: effects of aging, Parkinson’s disease, and associations with cognitive function

Experimental Brain Research (2025)