Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the effects of different shank types, tine types, and tractor forward speeds on the power and fuel consumption of chisel plows, stubble cover, soil surface roughness, and penetration resistance. In addition, using the obtained results, the draft power, fuel consumption, soil surface roughness, and soil stubble cover rate were modeled using Deep Learning Neural Network (DLNN) architectures and sensitivity analysis of these models were performed. Four different shank types (rigid, semi-spring, spring, and vibrating) and two different tine types (conventional and winged) were used at three different tractor forward speeds (4.5, 5.4 and 6.3 km.h− 1) were tested to this end. The obtained results indicated that the maximum draft power was achieved with the rigid type shank. The highest soil surface roughness values were observed for the vibrating shank type and winged tine type. Sixteen different network architectures were conducted using deep learning neural network methods and draft power, fuel consumption, soil surface roughness, and percent stubble cover were modeled. Sensitivity analyses were performed to indicate which modeled parameters were more sensitive to the factors using the obtained models. Draft power was modeled with 97.7% accuracy using the DLNN9 network architecture. Additionally, fuel consumption and soil roughness were best modeled with the DLNN13 network architecture, R2 values for those targets were 0.929 and 0.930 respectively. According to the sensitivity analysis, draft power, fuel consumption, soil roughness, and stubble cover rate were significantly affected by changes in the physical properties of the soil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tillage is the preparation of soil for crop production. There are numerous factors for plant growth, but one of the most important ones is soil tillage, owing to the effects on the soil environment condition, aeration, weed control, soil moisture content, soil strength, and nutrient distribution. Sustainable agriculture is a very important issue for agricultural production all over the world. Especially energy consumption should be taken into consideration to ensure sustainability in agricultural production, soil and water resources. Therefore, researchers strive to develop efficient agricultural equipment.

Past research has demonstrated that some type of simple tillage equipment, such as chisels, cultivators, cause less fuel consumption, less draft force1, reduced soil degradation, and increased yield2. Several studies have been carried out on different subjects such as single shearing elements3,4,5, whole tools6 and theoretical underpinnings7 to determine the effectiveness of these types of simple soil tillage equipment.

Conventional tillage is a practice that is increasingly being replaced with vertical tillage systems due to its excessive and adverse effects on the soil’s physical, chemical and biological qualities.The chisel plow, which is an important tillage equipment product in the vertical tillage system, is a widely used piece of equipment; it outperforms the traditionally-used moldboard and disc plows in terms of draft force, fuel consumption, soil disturbance, and soil roughness. The chisel plow consumes 40% less energy and working time than the conventional moldboard plow8.

In tillage reseach, draft force data is necessary for selecting the appropriate tractor power, properly designing tillage equipment, and determining the optimum operating conditions9 in tillage processes10. As such, numerous studies have been conducted, either in the field or in soil bin conditions, to determine draft power and fuel consumption3,7,11,12,13,14.

A substantial body of evidence has demonstrated that the consumption of fuel, draft power, and energy is affected by numerous factors such as soil type15, soil moisture content and bulk density16, depth and width of the cut17, the shape and geometry of the tine, tractor forward speed18, previous treatments16 and the cover crop15. A linear function between the draft power and tractor forward speed19, plowing depth, and width has been determined by some of the research. Lisowski et al.17 reported that increasing the forward speed, cutting width, and working depth increased the draft power of the tillage equipment with sweep type tine.

Abualgasim and Dahab20 demonstrated that the chisel plow has the highest draft, field efficiency, and fuel consumption compared to the other conventional tillage tools. According to El-Iraqi, et al.21, the modified chisel plow (4 rows Δ-shape) saved about 23–59% of power consumption and about 30–58% of the energy requirements compared to other types of chisel plows with 2 and 3 rows.

There are numerous shank types used with chisel plows. These shank types can be used in different variations depending on the soil type, soil moisture content, and bulk density. Lejman et al.22 stated that spring type shanks cause less energy consumption. In addition to these results, Al-Kheer et al.7 and Lisowski et al.17 argued that the rake angle of the cultivator affected the shearing resistance and therefore draft force.

Irregularity of the soil surface leads to soil surface roughness. Soil surface roughness is an important parameter in terms of sowing performance, seed emergence, erosion, infiltration, and overland flow23. Soil roughness is affected by soil texture, aggregate size, cover crop, tractor forward speed, tillage depth, and tillage implement24. Increasing working depth and tractor forward speed disturbs more soil, which in turn causes higher lateral soil movement thus increasing the degree of soil roughness25,26. Pullen and Cowell27 did not observe any significant difference in the soil roughness between the narrow-wing sweep and the conventional sweep.

Tools and machines used in agricultural production are quite difficult and complex to model because they interact with soil. In particular, it is challenging to model variables that do not have a linear relationship. Artificial neural networks have been successfully used to model parameters that exhibit non-linear relationships between their properties. The most recent study by Upadhyay et al.28 demonstrated the effectiveness of ANN and regression models in predicting the power requirement of agricultural machinery and further optimized the parameters using the ANN-PSO technique. For example, Shafaei et al.29 compared mathematical models and artificial neural network models in their studies to model the draft power of a disk plow, using the multiple linear regression model proposed by ASABE as the mathematical model. In this study where the tractor forward speed and soil tillage depth were taken into account as input parameters in the ANN model, the draft power was modeled with an accuracy rate of 97.1% with the ANN model.

Choi et al.30 developed a time-lagged recurrent neural network (TLRNN) to predict the dynamic draft of three kinds of tillage tools using tool shapes, shearing force, and cone index of soil as input parameters. They concluded that an ANN model could be a promising modeling approach for simulating the dynamic draft. In another study conducted to model the power consumption of a moldboard plow, cultivator, and disc harrow, the values of shearing width, forward speed, soil moisture content, and bulk density were utilized as input parameters using ANN. According to the results, the ANN method that was used in the study modeled power consumption with a lower error rate than the model proposed by ASABE. In the models produced by ANN, the error rate of all tillage equipment was found to be less than 6.5%, while in the modeling method proposed by ASABE, this rate was more than 30%31.

The aim of this study was to determine the effects of different shank types, tine types, and tractor forward speeds on the power and fuel consumption of chisel plows, stubble cover, soil surface roughness, and penetration resistance. In addition, using the obtained results, the draft power, fuel consumption, soil surface roughness, and soil stubble cover rate were modeled using Deep Learning Neural Network (DLNN) architectures and sensitivity analyses of these models were performed. Nine different parameters were utilized in modeling studies. These parameters are shank type (ST), tine type (TT), tractor forward speed (TFS), moisture content (MC), bulk density (BD), penetration resistance (PR), draft power (DP), stubble cover (SC), Fuel consumption (FC), and soil roughness (SR). In the study, 16 different DLNN architectures were used to obtain the best result and the models with the highest R2 value were identified. After identifying the best DLNN architecture for each model, sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the precision of draft power, fuel consumption, soil surface roughness, and stubble cover rate in relation to the factors considered in the study.

Materials and methods

Study site

The experiments were carried out under field conditions where wheat was harvested at 13 cm stubble length.The slope of the experiment field was less than 1% and the soil texture class was silty loam. Table 1 illustrates some soil physical properties of the experimental area.

Experimental design

The experimental plots were 50 m long and 3 m wide. In the experiments, four chisel plows with different shank types (rigid, semi-spring, spring, and vibrating) and two different tine types (conventional and winged) were used at three different tractor forward speeds (4.5 kmh− 1, 5.4 kmh− 1 and 6.3 kmh− 1). A vibrating chisel plow with 10 mm amplitude and 11 Hz frequency was also utilized alongside the standard chisel plow in the study. Technical specifications of the chisel plows used in the study are given in Table 2. Schematic drawings of the vibrating chisel plow, shank types, and tine types are shown in Figs. 1, 2 and 3 respectively. A Ford 5000 S Model tractor (49.4 kW, 2100 RPM) was used in the experiments.

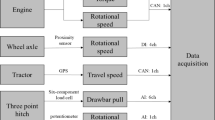

Determining power and fuel consumptions

Three draft pins with a 68 kN loading capacity and sensors for the horizontal component of the link forces were used to determine the draft force. The pins were connected to the tractor with three-point linkage. A calibration ring was used for the calibration of the pins. All records were kept between the starting point of the plots and the endpoint of the plots with 10 readings per second during the experiment. A Campbell Scientific CR1000X data logger was used to store data. A DJRVS II type radar unit was used to determine the tractor forward speed. A Cole Parmer IR-Opflow flow meter which has a flow range of 0.03–0.53 GPM was mounted between the fuel filter and injection pump of the tractor to determine tractor fuel consumption.

Draft power was calculated using draft force and forward speeds obtained from the data logger using Eq. 1.

Where Pd is draft power in kW, Fd is the draft force in kN and Vm is tractor forward speed in kmh− 1.

Determination of stubble cover, soil roughness, and penetration resistance

The line transaction method was used to determine the cover rate of stubble on the field surface before tillage. A 5 m rope marked at 10 cm intervals was used for this assesment. The percentage of residue coverage values were calculated after counting the pieces of crop residue corresponding to the marks on the rope32.

The chain method was used to determine the soil roughness and the measurements were taken perpendicular to the soil tillage direction. The values obtained were input into Eq. 2 for the calculation of soil roughness33.

Where R is soil roughness (%), L1 is the length of the chain in cm, and L2 is the horizontal projection length of the chain in cm.

An Eijkelkamp soil cone penetrometer (Eijkelkamp Agrisearch Equipment, Giesbeek, The Netherlands), which has an analog indicator was used for the measurement of penetration resistance before and after tillage. The penetration resistance measurements were made at 5 cm intervals up to a depth of 20 cm with three repetitions.

Deep learning neural network (DLNN) models

Two-hidden layer deep learning neural network (DLNN) models were utilized to model draft force, fuel consumption, soil roughness, and residue cover in the study. A Levenberg-Marquardt (trainlm) learning function and a logarithmic sigmoid (logsig) -symmetric sigmoid (tansig) function pair were used as transfer functions in all models. Sixteen unique DLNN models were obtained with the combination of different neuron numbers in the two hidden layers for the best model (Table 3). Table 4 shows the architectures of networks and parameters for inputs and outputs. An examination of Table 4 shows that 9 different input parameters were utilized to model draft power, fuel consumption, soil roughness, and stubble cover rate.

In the study, 70% of the data was used as a training set, 15% as a test set, and 15% as a verification set. The learning ability of the networks was determined by looking at the R2 values after the training and verification of the network performances. As a result of training the networks, it was concluded that the training and verification sets were trained if the R2 values of the networks were close to 1. MATLAB version: 9.13.0 (R2022b), Natick, Massachusetts: The MathWorks Inc. (https://www.mathworks.com/) software was used for all of the models and sensitivity analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed using the best DLNN architecture in each model. Relative importance values of each input parameter were separately given in sensitivity analyses. Input parameters were grouped and evaluated among themselves in the next stage. Soil condition (SC) was evaluated by gathering the results for soil roughness (SR) and stubble cover rates (STC). In another grouping, the sensitivity results of shank type (ST) and tine type (TT) were gathered and evaluated as the sensitivity of machine type (MT).

Lastly, sensitivity rates of moisture content (MC), bulk density (BD), and penetration resistance (PR) were collected and evaluated as soil physical properties (SPP). Draft power (DP) and tractor forward speed were not subjected to any grouping during sensitivity analyses. Table 5 shows the groupings used in sensitivity analyses. Equation 3 was used to determine the sensitivity analyses.

In the equation Ij is the percentage of the relative importance of the jth input variable on the neurons and Wih and Who are the matrices of weights between the input-hidden layer and hidden-output layer, respectively, N is the total number of neurons in the corresponding layer, and the subscripts ‘k’, ‘m’ and ‘n’ are indices referring to the neurons in the input, hidden and output layers, respectively34.

Performance evaluation for models and statistical analysis

The accuracy of the models was confirmed via “root-mean-square error” (also known as “root mean square deviation” or RMSE), “mean absolute error” (MAE), and R-Squared (also known as “coefficient of determination” or R2). A model is evaluated as high accuracy when R2 reaches 1 and RMSE and MAE approach zero. The values of RMSE, MAE, and R2 were calculated with Eqs. 4, 5 and 6, respectively.

In these equations; n is the number of observations, Ypi is the predicted value for observation i, Ydi is the real value for observation i, and Y is the average of the real values.

The data received from each experimental plot with three replications were analyzed statistically to test for differences among treatments. An ANOVA procedure was used to perform the analysis of variance, which was appropriate for a randomized complete block design. Means were separated by the Duncan test when treatment effects were significant. The threshold established for statistical significance was P < 0.01.

Result and discussion

Results of the draft power and fuel consumption

The experiments revealed statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) in draft power in all experimental factors (Table 6). The draft power varied from 8.29 kW to 11.8 kW. Among the shank types, the rigid shank had the highest average draft power consumption, while the lowest values were observed for the vibrating shank (Table 6). According to some authors, the vibration frequency of a shank influences shearing resistance, which as a result, causes a decrease in draft power35. At this point, it is possible that shank flexibility directly influences the vertical force7 and draft force17. Similar results were also determined in this study.

When the effect of tine type on draft force was examined, it was observed that the winged tine had a higher draft requirement compared to the conventional tine type (Table 6). The winged tine had a maximum draft power of 11.17 kW. However, in the plot tilled with the conventional tine, these values were determined as 9.3 kW. These results could be explained by the increase in contact surface area36,37. Similarly, Swick and Perumpral38 reported that soil shear strength and soil–metal friction increased with increasing draft consumption. In addition, Camacho and Magalhaes39 stated that the winged subsoiler reduced the specific soil resistance and decreased the draft power compared to the conventional chisel plow.

A linear function was observed between the tractor forward speeds and draft power in all the experiments. The increase in tractor forward speed increased the draft power (Table 6). While the maximum draft power was obtained at the 6.3 kmh− 1 tractor forward speed, the minimum values were observed at the 4.5 kmh− 1 tractor forward speed.

Significant differences (P < 0.001) were found in fuel consumption among the main factors in this study. The maximum fuel consumption values were observed for the rigid shank and winged tine as 8.6 l h− 1 and 9.38 l h− 1, respectively. In addition, the fuel consumption was 6.24 l h− 1 at the 4.5 km·h− 1 tractor forward speed; this value increases proportionally to speed and was determined as 9.53 l h− 1 at the 6.3 kmh− 1 tractor forward speed (Table 6). A linear function was observed between the draft power and fuel consumption in the experiment. This is commensurate with the work of some other authors who have previously found similar results19.

Soil roughness, stubble cover, and penetration resistance

Soil surface roughness was only affected by shank and tine type at a statistically significant (P < 0.001) level, but this effect was not observed for the other factors. The vibrating shank and winged tine types have the roughest soil surface with 91.2% and 94.28%, respectively (Fig. 4). Manuwa3 stated that the width of the tool strongly influences soil surface roughness. In this study, the winged type tine has more width compared to the conventional tine type; thus it caused more soil surface roughness.

The effects of the shank type on the stubble cover were statistically significant (P < 0.001), but this significance level was not observed for the other main factors. The Semi-spring (Ss) shank type pushed the residues towards the lower layers of the soil, therefore the minimum residue cover observed in the plot was for the Ss shank type with 63.42% (Fig. 5).

Penetration resistance was affected statistically significantly (P < 0.001) by shank and tine type at the 0–5 cm and 5–10 cm soil depths, but this effect was not observed for other factors and soil depths. Penetration resistance values are illustrated in Fig. 6. As demonstrated in Fig. 6, minimum penetration resistance values for the 0–5 cm soil depth were observed with the spring shank type and the conventional tine type with 0.007 MPa and 0.004 MPa, respectively. A direct relationship between the soil depth and penetration resistance was found in this study. the spring shank type and the conventional tine type had the minimum penetration resistance at 5–10 cm soil depth with 0.06 MPa and 0.037 MPa, respectively. Similar results were found by Di Prinzio et al.40. We found that the winged type tine caused more soil compaction compared to the conventional type tine.

Results of deep learning neural network models

The results of the statistical analysis of different network architectures created to model the draft power in the study are given in Appendix Table 7. The table shows that the best result was obtained with the DLNN 9 architecture.

In the DLNN 9 architecture, shank type, tine type, forward speed, moisture content, bulk density, penetration resistance, fuel consumption, stubble cover rate, and soil roughness values were used as input values and draft power was modeled. As in other architectures, the Levenberg-Marquardt function was used as the learning function in the DLNN 9 architecture, and Logarithmic sigmoid and Symmetric sigmoid function pairs were used as activation functions. In addition, 14 neurons were used in the first hidden layer and 12 in the second hidden layer in the DLNN 9 architecture. The DLNN 9 architecture predicted draft power with an accuracy of 97.7%. In this model, R2, RMSE and MAE values were obtained as 0.977, 0.044, and 0.063 respectively. The result of the regression analysis is shown in Fig. 7a, b ,which plots the observed values and the values of draft power predicted by the model produced by the DLNN 9 architecture.

The results of statistical analysis of the DLNN architectures created for modeling fuel consumption are given in Appendix Table 7. The best results were observed in the model produced by the DLNN 13 network architecture. In this architecture, Levenberg-Marquardt, and Logarithmic sigmoid-Symmetric sigmoid function pairs were used as learning and activation functions, respectively. In addition, 18 and 16 neurons were used in the first and second layer, respectively. Analyzing the statistical results of the DLNN 13 model revealed that fuel consumption was estimated with an accuracy of 92.9%. The R2, MAE, and RMSE values of the model were determined as 0.929, 0.089, and 0.163 respectively. The result of the regression analysis is shown in Fig. 8a and b with the observed values across predicted values produced by the model.

As with fuel consumption, as well as surface roughness, the best results were obtained in the DLNN 13 architecture (Table 7). With the DLNN 13 architecture, the surface roughness was estimated with an accuracy of 93%. The R² value for the DLNN 13 architecture, which was used to model surface roughness, was found to be 0.93, with a MAE of 0.106 and a RMSE of 0.156. The observed and predicted results of the network architecture of DLNN 13 used in the modeling of soil surface roughness and regression analysis are given in Fig. 9a, b.

The DLNN architectures performed to determine the condition of the soil stubble cover rate are given in Appendix Table 7. The table shows that the best model results are obtained with the DLNN 8 network architecture. However, the architectures that have endeavored to model the stubble cover rate have been modeled with a lower accuracy rate than the other models. According to the DLNN 8 network architecture, the stubble cover rate was modeled with an accuracy of 67.1%. The R2 value in this architecture was calculated as 0.671, the MAE value was calculated as 0.117, and the RMSE value was calculated as 0.241. The estimated and observed values of the DLNN 8 network and regression analysis are given in Fig. 10a, b.

The results obtained in this study are parallel to other studies conducted on the subject. For example, Akbarnia et al.41 used the ANN backpropagation learning algorithm in their research to model the power consumption of tillage equipment with different foot types and predicted the power consumption with an error rate of 0.56. Zhang and Kushwaha42 used the Radial Basis Function (RBF) Neural Network to model the power consumption of tillage equipment with a narrow foot type. Power consumption has been successfully modeled in research where forward speeds, foot types, and soil types are used as input parameters. This aligns with the findings of Upadhyay et al.28, who also employed ANN-based models optimized with ANN-PSO techniques to predict the power requirement of agricultural machinery with high accuracy.

Al-Janobi et al.43 developed a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) network with an error backpropagation (BP) learning algorithm to model the power consumption of a chisel plow, offset disk rake, and moldboard plow. Power consumption was modeled with an accuracy of 98.7% in this study, where the machine type, tillage depth, and forward speed were evaluated as input parameters. In another study conducted for ANN modeling of energy consumption at the time of tillage, tractor forward speed and depth of tillage on some soil physical properties (moisture content, penetration resistance, soil clay content) were evaluated as input parameters. Energy consumption was modeled with an accuracy of 97.6% in the study using a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) network with an error backpropagation (BP) learning algorithm.

Results of sensitivity analysis

In the present study, sensitivity analyses were performed using DLNN architectures, which provide the best results for modeling draft power, fuel consumption, soil surface roughness, and stubble cover rate. The purpose of the sensitivity analysis was to determine how sensitive the power and fuel consumption, soil surface roughness formed after tillage, and the distribution rate of stubble on the soil surface were, for which input parameters were used in the study. Sensitivity analyses were carried out regarding draft power, fuel consumption, soil surface roughness, and soil stubble cover rate to this end by taking into account the parameters described in Table 5.

The DLNN 9 network architecture that best models the draft power was used in the sensitivity analysis of the draft power. According to the sensitivity analyses, it was concluded that the draft power consumption was most sensitive to changes in soil physical properties with 34.02%. This significant impact of soil physical properties is likely due to their direct influence on the mechanical interaction between the tillage tool and the soil, such as draft force and penetration resistance, which are key factors in determining the required power. Soil physical properties were followed by machine type with 23.67% and soil condition with 19.71%. In addition, the sensitivity results for tractor forward speed and fuel consumption were determined as 13.86% and 8.74%, respectively (Fig. 11).

Sensitivity analysis of fuel consumption using the DLNN 13 network architecture. Figure 11 shows the results of the sensitivity analysis of fuel consumption. As can be seen from the figure, it was determined that fuel consumption is most sensitive to the physical properties of the soil with 33.8%. The high sensitivity to soil physical properties emphasizes the critical role of soil moisture content, bulk density, and texture in influencing fuel consumption during tillage operations. This is because these properties affect soil compaction, leading to variations in the required energy for effective tillage. This was followed by machine type values with 23.8%, soil condition with 19.72%, tractor forward speed with 12.98%, and draft power values with 10.01%. As expected, the results of the sensitivity analysis of fuel consumption and the results of the draft power are parallel.

Sensitivity analyses of the surface roughness were performed using the DLNN 13 architecture, which best models roughness. According to the results obtained, it was determined that surface roughness is more sensitive to the physical properties of soil (36.3%). This finding aligns with previous research that highlights the strong correlation between soil texture and surface roughness after tillage, where coarser soils tend to exhibit higher surface irregularities post-tillage. Soil physical properties can change soil behavior under tillage tools, thus impacting soil displacement and roughness. In addition, the result of the sensitivity analysis for machine type was determined as 19.1%; soil condition, draft power, and tractor forward speed values were calculated as 13.1%, 12.9%, and 8%, respectively (Fig. 11).

As with other results, it was concluded that the rate of covering the soil with stubble was more sensitive to changes in soil physical properties with 39.86%. The particularly high sensitivity to soil physical properties can be attributed to the way different soil structures react to tillage, especially in terms of how crop residues are incorporated back into the soil surface. The stubble cover condition was affected by the change in machine type with an accuracy of 19.55%. However, the sensitivity analysis results of the draft power, soil condition, and tractor forward speed were calculated as 11.26%, 9.96%, and 7.56%, respectively (Fig. 11).

As can be seen from the results, the highest ratios were obtained for soil physical properties in sensitivity analyses. In the study, soil physical properties, bulk density, porosity, and moisture content were evaluated as the sum of sensitivity analyses in the grouping of sensitivity analyses. It is essential to note that these parameters collectively play a pivotal role in determining the energy requirements for effective tillage, influencing the draft power, fuel consumption, and surface roughness outcomes. It has been determined that the second-greatest factor after the physical properties of the soil is the machine type, which consists of the sum of sensitivity analyses of the shank type and tine type.

Conclusions

A study was conducted in field conditions to determine the effects of different shank and tine types of chisel, and tractor forward speeds on draft force, fuel consumption, soil roughness, stubble cover rate, and penetration resistance. In addition, using the obtained results, the draft power, fuel consumption, soil surface roughness, and soil stubble cover rate were modeled using DLNN network architectures and sensitivity analyses of these models were performed.

Among the shank types, the rigid shank had the highest average draft force and draft power consumption. The winged tine type had the maximum draft requirement compared to the conventional tine type. In addition to the results, an increase in tractor forward speed increased fuel consumption. The maximum fuel consumption values were recorded for the vibration shank and winged tine. A linear function between the draft power and fuel consumption was observed in the experiment. Soil surface roughness was only affected by shank and tine type. The vibrating shank and winged tine caused the most soil surface roughness. The semi-spring shank type pushed the residues towards the lower layers of the soil so a minimum residue cover was observed in the plot using the semi-spring shank type. Minimum penetration resistance values were observed for the spring shank type and conventional tine type. We found that there is a linear relationship between soil depth and penetration resistance.

Draft power was modeled with an accuracy of 97.7% in the study, using the DLNN 9 network architecture. In addition, the DLNN 13 network architecture modeled the fuel consumption and soil surface roughness best. The R2 values obtained in the fuel consumption and soil surface roughness models were determined as 0.929 and 0.930, respectively. A lower R2 value (0.671) was obtained in the model created for the soil stubble soil covering condition compared to the other models. According to the results of the sensitivity analysis, draft power, fuel consumption, surface roughness, and stubble cover rate exhibited a more sensitive response to changes in the physical properties of the soil. Following soil physical properties, the change in other parameters was most affected by the type of shank and tines.

Data availability

All data supporting the conclusions of this article are included in this article.

References

Chen, Y., Cavers, C., Tessier, S., Monero, F. & Lobb, D. Short-term tillage effects on soil cone index and plant development in a poorly drained, heavy clay soil. Soil Tillage. Res. 82, 161–171 (2005).

De Rouw, A. et al. Possibilities of carbon and nitrogen sequestration under conventional tillage and no-till cover crop farming (Mekong Valley, Laos). Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 136, 148–161 (2010).

Manuwa, S. Performance evaluation of tillage tines operating under different depths in a sandy clay loam soil. Soil Tillage. Res. 103, 399–405 (2009).

Sahu, R. K. & Raheman, H. An approach for draft prediction of combination tillage implements in sandy clay loam soil. Soil Tillage. Res. 90, 145–155 (2006).

Zhang, X. & Chen, Y. Soil disturbance and cutting forces of four different sweeps for mechanical weeding. Soil Tillage. Res. 168, 167–175 (2017).

Al-Janobi, A. A., Wahby, M. F., Aboukarima, A. M. & Al-Hamed, S. A. Physical processes affecting microbial habitats and activity in unsaturated porous media. J. Agricultural Mar. Sci. [JAMS]. 7, 39–45 (2002).

Al-Kheer, A. A., Kharmanda, M. G., Hami, E., Mouazen, A. M. & A. & Estimating the variability of tillage forces on a chisel plough shank by modeling the variability of tillage system parameters. Comput. Electron. Agric. 78, 61–70 (2011).

Aboukarima, A. Draft models of chisel plow based on simulation using artificial neural networks. Misr J. Ag Eng. 24, 42–61 (2007).

Ademosun, O. The design and operation of a soil tillage dynamics equipment. Nigerian Eng. 25, 51–57 (1990).

Alimardani, R., Fazel, Z., Akram, A., Mahmoudi, A. & Varnamkhasti, M. Design and development of a three-point hitch dynamometer. J. Agricultural Technol. 4, 37–52 (2008).

Askari, M., Komarizade, M., Nikbakht, A., Nobakht, N. & Teimourlou, R. A novel three-point hitch dynamometer to measure the draft requirement of mounted implements. Res. Agricultural Eng. 57, 128–136 (2011).

Kheiralla, A. F., Yahya, A., Zohadie, M. & Ishak, W. Modelling of power and energy requirements for tillage implements operating in Serdang sandy clay loam, Malaysia. Soil Tillage. Res. 78, 21–34 (2004).

Manuwa, S. & Ademosun, O. Draught and soil disturbance of model tillage tines under varying soil parameters. (2007).

Ramadhan, M. Development and performance evaluation of the double tines subsoiler in silty clay soil part 1: draft force, disturbed area and specific resistance. Mesop. J. Agric. 42, 293–313 (2014).

Baloch, J., Mirani, A. & Bukhari, S. Prediction of field performance of wheel tractors. (1991).

Mouazen, A. M. & Ramon, H. A numerical–statistical hybrid modelling scheme for evaluation of draught requirements of a subsoiler cutting a sandy loam soil, as affected by moisture content, bulk density and depth. Soil Tillage. Res. 63, 155–165 (2002).

Lisowski, A. et al. Duckfoot tools connected with flexible and stiff tines: three components of resistances and soil disturbance. Soil Tillage. Res. 158, 76–90 (2016).

Glancey, J. L., Upadhyaya, S. K., Chancellor, W. J. & Rumsey, J. W. Prediction of agricultural implement draft using an instrumented analog tillage tool. Soil Tillage. Res. 37, 47–65 (1996).

Grisso, R., Yasin, M. & Kocher, M. Tillage implement forces operating in silty clay loam. (1996).

Abualgasim, M. R. & Dahab, M. H. The study of suitable effective use of machinery in farming research station (Elrawakeeb) west of Khartoum-Sudan. Res. J. Agric. Env Manag. 2, 164–168 (2013).

El-Iraqi, M., Marey, S. & Drees, A. M. A modified triangle-shape chisel plow (evaluation and performance test). Misr J. Agricultural Eng. 26, 644–666 (2009).

Lejman, K., Owsiak, Z., Pieczarka, K. & Sekutowski, T. Vertical forces acting on cultivator tines in the aspect of shearing speed and flexibility of tines. Agricultural Eng. 22, 39–48 (2018).

Altıkat, S. & Çelik, A. Effects of different furrow openers, covering components and forward speeds in no till seeders on the soil surface roughness. J. Inst. Sci. Technol. 1, 91–96 (2011).

Amoah, J. K., Amatya, D. M. & Nnaji, S. Quantifying watershed surface depression storage: determination and application in a hydrologic model. Hydrol. Process. 27, 2401–2413 (2013).

Cirujeda, A., Melander, B., Rasmussen, K. & Rasmussen, I. A. Relationship between speed, soil movement into the cereal row and intra-row weed control efficacy by weed harrowing. Weed Res. 43, 285–296 (2003).

Sharifat, K. & Kushwaha, R. Lateral soil movement by tillage tools. (1999).

Pullen, D. & Cowell, P. An evaluation of the performance of mechanical weeding mechanisms for use in high speed inter-row weeding of arable crops. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 67, 27–34 (1997).

Upadhyay, G., Kumar, N., Raheman, H. & Dubey, R. Predicting the Power Requirement of Agricultural Machinery Using ANN and Regression models and the optimization of parameters using an ANN–PSO technique. AgriEngineering 6, 185–204 (2024).

Shafaei, S. M., Loghavi, M. & Kamgar, S. A comparative study between mathematical models and the ANN data mining technique in draft force prediction of disk plow implement in clay loam soil. Agricultural Eng. International: CIGR J. 20, 71–79 (2018).

Choi, Y. S., Lee, K. S. & Park, W. Y. Application of a neural network to dynamic draft model. Agricultural Biosystems Eng. 1, 67–72 (2000).

Roul, A., Raheman, H., Pansare, M. & Machavaram, R. Predicting the draught requirement of tillage implements in sandy clay loam soil using an artificial neural network. Biosyst. Eng. 104, 476–485 (2009).

Altikat, S., Celik, A. & Gozubuyuk, Z. Effects of various no-till seeders and stubble conditions on sowing performance and seed emergence of common vetch. Soil Tillage. Res. 126, 72–77 (2013).

Saleh, A. Soil roughness measurement: chain method. J. Soil Water Conserv. 48, 527–529 (1993).

Aleboyeh, A., Kasiri, M., Olya, M. & Aleboyeh, H. Prediction of azo dye decolorization by UV/H2O2 using artificial neural networks. Dyes Pigm. 77, 288–294 (2008).

Fenyvesi, L. & Hudoba, Z. Vibrating tillage tools. Soil. Eng., 31–49 (2010).

Raper, R. L. & Schwab, E. B. Development of an in-row subsoiler attachment to reduce smearing. Appl. Eng. Agric. 25, 495–503 (2009).

Tice, E. & Hendrick, J. Disc coulter forces: evaluation of mathematical models. Trans. ASAE. 34, 2291–2298 (1991).

Swick, W. & Perumpral, J. A model for predicting soil-tool interaction. J. Terrramech. 25, 43–56 (1988).

Camacho, J. H. & Magalhães, P. S. Estudio De parámetros operacionales de discos dobles y cinceles parabólicos para prácticas culturales en áreas con residuos vegetales. Agricultura Técnica. 64, 58–65 (2004).

Di Prinzio, A., Ayala, C. & Magdalena, J. Energy evaluation of different techniques and subsoiling effects on soil bulk density. Agro-Science 13, 61–67 (1997).

Akbarnia, A., Mohammadi, A., Alimardani, R. & Farhani, F. Simulation of draft force of winged share tillage tool using artificial neural network model. Agricultural Eng. International: CIGR J. 16, 57–65 (2014).

Zhang, Z. & Kushwaha, R. Applications of neural networks to simulate soil-tool interaction and soil behavior. Can. Agricultural Eng. 41, 119 (1999).

Al-Janobi, A., Aboukarima, A. & Ahmed, K. A. Prediction of specific draft of different tillage implements using neural networks. Misr J. Agricultural Eng. 18, 669–714 (2001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. conceptualization, field studies, data collection and writing. A.C. conceptualization, supervision, data collection, review and editing. M.G.B. data curation, writing, review and editing. M.Z.M. data curation, technical and spelling checking, reviewed the manuscript. A.A. development of the models, final revisions, and in preparing the responses to the reviewers.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Altikat, S., Celik, A., Boydas, M.G. et al. Chisel plow characteristics impact on power-fuel consumption, stubble cover, and surface roughness using deep learning neural networks with sensitivity analysis. Sci Rep 14, 28804 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80253-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80253-0