Abstract

Serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein (LRG) can monitor disease activities during biologics treatment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It is unclear whether the pretreatment serum LRG level can predict clinical effectiveness including serum trough levels of ustekinumab in patients with IBD. This multicenter prospective cohort study included 184 patients (Crohn’s disease, 104; ulcerative colitis, 80) who received ustekinumab (n = 119) or anti-tumor necrosis factor (n = 65) between January 2019 and March 2023. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed serum LRG level at week 0 (0w-LRG, odds ratio 0.12, 95% confidence interval 0.02–0.68) as one of significant factors for clinical remission at week 8. We divided patients into the low- and the high-LRG groups by the median 0w-LRG (18.2 µg/mL) and compared the effectiveness. In patients who received ustekinumab, the proportion of clinical remission at week 8 was significantly different between in the low- (76.9%) and in the high-LRG group (59.3%, P = 0.038), and median serum trough level at week 8 was significantly different between in the low- (10.9 µg/mL, interquartile range 6.7–13.4) and the high-LRG group (5.3 µg/mL, interquartile range 2.4–8.3, P < 0.001). The 0w-LRG can predict the effectiveness including serum trough levels of ustekinumab during induction treatment for patients with IBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are refractory conditions characterized by chronic gastrointestinal inflammation and unclear etiologies and their prevalence is increasing worldwide1,2. However, advanced therapy with biologic agents (hereafter referred to as biologics) or small-molecule drugs has become available for patients with IBD3,4. Appropriate advanced therapy to achieve and maintain clinical remission (CR) and mucosal healing can reduce hospitalization and surgery requirements, ultimately preserving the quality of life5,6.

Several randomized controlled studies and network meta-analyses that compared the efficacy of advanced therapy for patients with IBD have been performed4,7,8,9,10,11. However, real-world comparative studies on the effectiveness of advanced therapy in patients with IBD were limited12,13. Additionally, guidelines that define the criteria for the selection of advanced therapy for patients with IBD are scarce2,14,15,16,17, and the selection is, thus, often based on the physician’s discretion.

Randomized controlled studies have demonstrated that, in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC) who received ustekinumab (UST) or adalimumab (ADA), the proportion of CR was elevated to 50–60% at week 8 and then slightly elevated to 60–70% at week 529,10. Achieving CR in the short term, stated in STRIDE-II as a treatment target, is important in the selection of biologics because it leads to long-term prognosis improvement in patients with IBD5,6. Furthermore, serum trough levels of biologics are useful parameters in treatment with biologics18,19,20,21,22; however, biomarkers for predicting the effectiveness and serum trough levels of biologics during induction treatment are unclear but important for selecting biologics in patients with IBD.

Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein (LRG) is a 50-kDa glycoprotein, first reported by Haupt et al., that contains eight leucine-rich repeat domains23. Serum LRG, which can be measured similarly to serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum albumin (Alb), is a novel biomarker that reflects clinical symptoms, endoscopic activity, and transmural inflammation in patients with IBD24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Furthermore, in the PLANET study, it was reported that, in patients with IBD, serum LRG could monitor disease activities, including endoscopic activities, and predict the serum trough levels of ADA better than serum CRP levels during ADA treatment32,33. However, it remains unclear whether the pretreatment level of serum LRG can predict clinical effectiveness including serum trough levels of UST during induction treatment, and can assist in selecting the appropriate anti-cytokine biologics (anti-tumor necrosis factor; anti-TNF or UST) for patients with IBD.

This study aimed to investigate the association between serum biomarkers, including serum LRG levels and serum trough levels of biologics, and the anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness of during induction treatment. We assessed whether serum LRG could predict the anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness including serum trough levels to aid the selection of appropriate anti-cytokine biologics by pretreatment levels of serum LRG.

Methods

Study design and patients

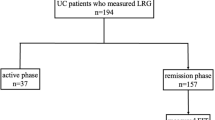

This multicenter prospective cohort study enrolled patients aged ≥ 16 years from 15 hospitals participating in the Osaka Gut Forum between January 2019 and March 2023. All included patients were diagnosed with IBD (including UC or CD) and had begun treatment with anti-cytokine biologics (infliximab [IFX], ADA, or UST) owing to corticosteroid dependence or resistance or other reasons that made treatment with existing therapies, such as corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and 5-aminosalicylic acid, difficult. In total, 184 patients treated with UST, IFX, and ADA were included in this study, and their serum LRG levels were all investigated at weeks 0 and 8. Only nine patients with UC who received golimumab (GOL) was excluded in this study because the number of patients was too small to analyze and we had not established to measure serum trough levels of GOL. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the involved ethics committee of Osaka University Hospital (No. 18209) and the other ethics commitees (Table S1). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Data collection and treatment

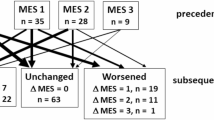

Clinical characteristics, including sex, age, disease duration, body mass index, IBD type (UC or CD), disease phenotype, smoking status (current, past, or never), concomitant drugs (corticosteroids or immunomodulators), and endoscopic activity within 3 months before initiation of the anti-cytokine biologics treatment were recorded before initiation of the biologics treatment. Clinical activities and the levels of LRG, CRP and Alb, as covered by insurance, were assessed at weeks 0 and 8 of anti-cytokine biologics treatment. Serum LRG levels were measured in the stored blood samples by research funding (if not covered by Japanese health insurance) using a NANOPIA LRG Kit (Sekisui Medical, Tokyo, Japan) based on the latex turbidimetry method. Serum CRP levels and serum Alb levels were measured based on the latex immunoturbidimetry method and modified bromcresol purple method, respectively. Clinical activities were evaluated based on the partial Mayo score (PMS) for UC34 and the CD activity index (CDAI) for CD35. Endoscopic activity was evaluated based on the Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) for UC34 and the Crohn’s endoscopic index of severity (CDEIS) for CD36 using colonoscopy or transanal double-balloon enteroscopy. We defined CR as a PMS of ≤ 2, with each subscore of 0 or 1 and a CDAI of < 15037.

Blood sample collection and measurements

Blood samples for measuring serum trough levels of UST, IFX, and ADA or serum LRG levels were collected and stored at − 80 °C before a new infusion at week 8 (Figure S1). Serum trough levels were measured using an LCMS-8060 quadrupole mass spectrometer (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan), as previously reported, with some modifications38,39,40. Briefly, to obtain peptides from the fragmented antigen-binding region of immunoglobulin G, serum samples were pretreated using the nSMOL Antibody BA Kit (Shimadzu Corp.) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The lower quantitation limits for UST, IFX, and ADA were 0.391, 0.293, and 0.977 µg/mL, respectively.

Treatment

At week 0, UST was administered intravenously at 520 mg (body weight [BW]: >85 kg), 390 mg (BW: 55–85 kg), or 260 mg (BW: <55 kg), followed by a 90 mg subcutaneous dose at week 8, and the same doses thereafter every 8 or 12 weeks. IFX was administered intravenously at 5 mg/kg BW at weeks 0, 2, and 6 during the induction phase and subsequently every 8 weeks during the maintenance phase. ADA was administered at 160 mg subcutaneously at week 0, followed by 80 mg at week 2, and then 40 mg every alternate week. During the maintenance phase, the IFX doses could be doubled or the duration shortened in patients with CD, and the ADA doses could be doubled in patients with CD or UC.

Outcomes

First, we assessed whether the anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness at week 8 could be predicted by clinical characteristics or serum biomarkers, including serum LRG level at week 0 (0w-LRG). The anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness was assessed based on CR and steroid-free CR (SF-CR). Second, we investigated the association between 0w-LRG and serum trough levels of anti-cytokine biologics at week 8 and assessed whether 0w-LRG could predict serum trough levels of anti-cytokine biologics during induction treatment.

Statistical analyses

Continuous parametric variables between different groups were assessed using the Student t-test, whereas non-parametric variables were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Pearson’s chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test was used to assess differences for categorical data. Logistic regression analysis with the stratification variables was used to assess the odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The number of factors in the multivariate analysis was defined as those almost one-tenth of the number of events. Disease types, clinical symptoms and endoscopic scores assessed differently in CD and UC were excluded from the analysis. Area under curve (AUC) values in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used for investigating the cutoff value of the biomarkers. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was performed to analyze the association between the biomarkers and serum trough concentrations of anti-cytokine biologics. P values < 0.05 were set as statistically significant. We used the available-case analysis to deal with the missing data. All analyses were performed using JMP statistical software (version 17.0.0; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 1 presents the pretreatment clinical characteristics and disease activities of 184 patients (104 with CD and 80 with UC) at week 0 of anti-cytokine biologics treatment. Among them, 119 (64.6%), 33 (17.9%), and 32 (17.4%) patients received UST, IFX, and ADA, respectively. Notably, 57 (31.0%) patients had previous exposure to anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) before initiation of the present biologic treatment. Concomitant corticosteroids and immunomodulators at week 0 were received 63 (34.2%) and 64 (34.8%) patients, respectively. Upon stratifying all patients into those receiving UST and those receiving anti-TNF treatment (IFX or ADA), patients who received UST were older (42 [29–52] years, P = 0.021), had longer disease duration (7.0 [1.0–16.0] years, P = 0.007), and had a higher proportion of anti-TNF exposure (36.1%, P = 0.040, Table S2). Anti-TNF agents were administered to patients with higher 0w-LRG (21.3 µg/mL [14.7–33.8], P = 0.013), whereas patients with lower 0w-LRG (16.8 [11.8–25.2]) received UST.

The correlation between anti-ctytokine biologics’ effectiveness and serum LRG levels at week 8

We investigated the correlation between anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness and serum LRG levels at week 8 (8w-LRG). In patients with IBD who received UST, median 8w-LRG in patients with CR (12.1 [10.0-15.7]) or SF-CR (12.0 [9.8–15.7]) at week 8 were significantly lower than in patients with non CR (16.7 [10.7–24.0], P = 0.029) or non SF-CR (14.1 [11.2–21.5], P = 0.042) at week 8 (Figure S2a or S2c). In patients with IBD who received anti-TNF treatment, median 8w-LRG in patients with CR (13.0 [10.5–18.0]) or SF-CR (12.7 [10.2–17.2]) at week 8 were significantly lower than in patients with non CR (30.1 [19.1–35.2], P < 0.001) or non SF-CR (25.8 [13.0-33.1], P < 0.001) at week 8 (Figure S2b or S2d).

Factors associated with anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness at week 8

We investigated the factors associated with anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness at week 8 using univariate followed by multivariate logistic regression analysis because patients with IBD who received UST and anti-TNF treatment exhibited different clinical characteristics and disease activities, including serum biomarker levels at week 0 (Table S2). When the factors associated with CR at week 8 were examined by multivariate analysis, 0w-LRG (OR: 0.12 [95% CI 0.02–0.68]) and anti-TNF/UST (OR: 2.34 [95% CI 1.01–5.40]) were identified as significant factors for CR at week 8 (Table 2).

We investigated the cutoff values of biomarkers to predict the anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness at week 8 with ROC analysis. In both patients who received UST and anti-TNF, the AUCs of all biomarkers at week 0 for predicting CR at week 8 were low (Table S3). Therefore, we investigated whether the anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness at week 8 could be predicted using median values.

Prediction of anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness at week 8 using serum LRG levels at week 0

We investigated whether the anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness at week 8 could be predicted using median 0w-LRG (18.2 µg/mL). We defined the low-LRG group as 0w-LRG < 18.2 µg/mL, the high-LRG group as 0w-LRG ≥ 18.2 µg/mL. In patients who received UST, the proportions of CR and SF-CR, at week 8 were significantly different between in the low-LRG group (76.9% [95% CI 65.4–85.5] and 63.1% [95% CI 50.9–73.8]) and in the high-LRG group (59.3% [95% CI 46.0–71.3] and 44.4% [95% CI 32.0–57.6], P = 0.038 and P = 0.042, respectively; Fig. 1a,c). However, in patients who received anti-TNF treatment, the proportions of CR and SF-CR was not significantly different between in the low-LRG group (84.6% [95% CI 66.5–93.9] and 76.9% [95% CI 57.9–89.0], respectively) and in the high-LRG group (82.1% [95% CI 67.3–91.0] and 66.7% [95% CI 51.0–79.4], P = 0.781 and P = 0.373; Fig. 1b,d). In addition, we investigated the factors associated with the effectiveness of UST at week 8 in patients with IBD using univariate followed by multivariate logistic regression analysis including disease phenotype (CD/UC) which was an important confounding factor (Table 3) because the low- and high-LRG groups exhibited different clinical characteristics (Table S4). When the factors associated with CR at week 8 were examined, only 0w-LRG was identified as a significant factor (OR: 0.09 [95% CI 0.01–0.86]). When the factors associated with CR at week 8 in patients who received anti-TNF were examined using univariate logistic regression analysis (Table S5), 0w-LRG was not identified as a significant factor (OR: 0.24 [95% CI 0.02–2.86]).

Effectiveness of UST or anti-TNF treatment in patients with IBD using median 0w-LRG. The proportion of CR in patients with low- or high-LRG at week 8 of treatment with UST (a) and anti-TNF treatment (b). The proportion of SF-CR in patients with low- or high-LRG at week 8 of treatment with UST (c) and anti-TNF treatment (d). The low-LRG group is defined as 0w-LRG < 18.2 µg/mL and the high-LRG group as ≥ 18.2 µg/mL.

Prediction of anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness at week 8 using serum CRP or Alb levels at week 0

We investigated whether the anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness at week 8 could be predicted using median serum CRP levels at week 0 (0w-CRP, 0.19 mg/dL) or median serum Alb levels at week 0 (0w-Alb, 3.9 g/dL). We defined the low-CRP group as 0w-CRP < 0.19 mg/dL, the high-CRP group as 0w-CRP ≥ 0.19 mg/dL, the low-Alb group as 0w-Alb < 3.9 g/dL, and the high-Alb group as 0w-Alb ≥ 3.9 g/dL. The proportions of week 8 CR in patients receiving UST were not significantly different between the low-CRP group (75.0% [95% CI 63.2–84.0]) and the high-CRP group (61.8% [95% CI 48.6–73.5]), P = 0.121; Fig. 2a), similar to patients receiving anti-TNF treatment (CR in low- and high-CRP group: 89.3% [95% CI 72.8–96.3] and 78.4% [95% CI 62.8–88.6], respectively, P = 0.245; Fig. 2b). The proportions of week 8 CR in patients receiving UST were not significantly different between the low-Alb group (64.8% [95% CI 51.5–76.2]) and the high-Alb group (72.3% [95% CI 60.4–81.7], respectively, P = 0.379; Fig. 2c), similar to patients receiving anti-TNF treatment (CR in low- and high-Alb group: 77.8% [95% CI 61.9–88.3] and 89.7% [95% CI 73.6–96.4], respectively, P = 0.204; Fig. 2d).

Effectiveness of UST or anti-TNF treatment for patients with IBD using median 0w-CRP or 0w-Alb. The proportion of CR in patients with low- or high-CRP at week 8 of treatment with UST (a) and anti-TNF treatment (b). The proportion of CR in patients with low- or high-Alb at week 8 of treatment with UST (c) and anti-TNF treatment (d). The low-CRP group is defined as 0w-CRP < 0.19 mg/dL and the high-CRP group as ≥ 0.19 mg/dL. The low-Alb group is defined as 0w-Alb < 3.9 g/dL and the high-Alb group as ≥ 3.9 g/dL.

Prediction of serum trough levels of biologics at week 8 using 0w-LRG

We investigated whether the median 0w-LRG (18.2 µg/mL) could predict the serum trough levels of anti-cytokine biologics at week 8. The median serum trough level of UST was significantly different between in the low-LRG group (10.9 µg/mL, IQR 6.7–13.4) and in the high-LRG group (5.3 µg/mL, IQR 2.4–8.3, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3a). However, due to the large variation in the median serum trough levels of IFX in the high-LRG group, the median serum trough levels were not significantly different between the low-LRG group (16.5 µg/mL, IQR 4.9–20.5) and the high-LRG group (4.6 µg/mL, IQR 0.2–14.1, P = 0.118) (Fig. 3b). Median serum trough concentrations of ADA were also not significantly different between the low-LRG group (12.3 µg/mL, IQR 7.2–16.4) and the high-LRG group (10.4 µg/mL, IQR 7.2–16.4, P = 0.590) (Fig. 3c). Owing to a sufficient number of patients with IBD receiving UST, we categorized patients into those with CD or those with UC and investigated whether median 0w-LRG could predict serum trough levels of UST at week 8. In patients with CD, the median serum trough level of UST was significantly different between in the low-LRG group (8.2 µg/mL, IQR 5.3–12.6) and in the high-LRG group (4.7 µg/mL, IQR 2.3–8.1, P < 0.001) (Figure S3a). In patients with UC, the median serum trough level of UST was significantly different between in the low-LRG group (11.6 µg/mL, IQR 9.3–14.4) and in the high-LRG group (5.4 µg/mL, IQR 3.4–8.6, P = 0.002) (Figure S3b). Furthermore, we assessed the correlation between biomarkers at week 0 and serum trough levels of anti-cytokine biologics at week 8 in patients with IBD. In patients who received UST, IFX or ADA, 0w-LRG (−0.379, −0.343 or −0.321) was correlated with serum trough levels at week 8 better than 0w-CRP (−0.260, −0.271 or −0.323) or 0w-Alb (0.311, 0.276 or 0.245, Table S6).

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated whether 0w-LRG level can predict the anti-cytokine biologics’ effectiveness including serum trough levels at week 8 and if this pretreatment level of serum LRG can assist in selecting the appropriate anti-cytokine biologics for patients with IBD. We demonstrated that in patients with IBD who received anti-cytokine biologics, the pretreatment level of serum LRG was one of significant factors for CR, which could predict the effectiveness including serum trough levels of UST at week 8. The strength of this cohort study lies in its prospective multicenter design, including an academic institution and 14 non-academic institutions, which provided real-world data. Furthermore, we evaluated the serum trough levels of anti-cytokine biologics and demonstrated that the pretreatment levels of serum LRG could predict the effectiveness including serum trough levels of UST during induction treatment, which can serve as a biomarker for selecting anti-cytokine biologics in patients with IBD.

In this study, compared to patients with IBD who received anti-TNF treatment, patients with IBD who received UST had a longer disease duration, a higher proportion of anti-TNF exposure, and lower disease activity, including serum LRG levels. These results may reflect the historical context in which IFX, ADA, and UST became available for patients with IBD and the context of the current guidelines2,14,15,16,17. This study also included patients with IBD who were not eligible in the randomized controlled trial since we incorporated all patients without any restrictions on disease activities, comorbidities, corticosteroid, or other pretreatment medication prior to the induction of biologics, as long as they were ≥ 16 years and could independently provide consent9,10. Furthermore, we demonstrated that serum LRG levels reflected disease activites during induction treatment in patients with IBD who received UST or anti-TNF treatment. This result aligns with previous reports that serum LRG can monitor disease activities including endoscopic activity during biologics treatment in patients with IBD24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Our results are, therefore, clinically applicable and represent real-world scenarios.

Regarding the comparison of the effectiveness of UST and anti-TNF treatment, the results of this study, including confounding factors, demonstrated that the anti-cytokine biologics selection (UST or anti-TNF treatment) and 0w-LRG were significantly associated with CR at week 8 in patients with IBD. In patients with IBD who received UST, 0w-LRG was the only significant factor associated with CR during induction treatment, and there was a significant difference in treatment effectiveness depending on serum LRG levels, unlike anti-TNF treatment. In particular, in the high-LRG group, the proportion of SF-CR in patients with IBD who received UST was < 45%, whereas in those who received anti-TNF treatment, it was approximately 70%. Therefore, in patients with IBD who need to discontinue corticosteroids within the short term or cannot receive concomitant corticosteroids at the initiation of biologics, anti-cytokine biologics selection may optimize the short-term treatment effectiveness.

Pretreatment level of serum LRG was reported as more useful in predicting serum trough levels at week 12 in patients who received ADA33, and we first demonstrated that pretreatment level of serum LRG could predict serum trough levels at week 8 of UST in addition to anti-TNF better than that of serum CRP or serum Alb. Furthermore, in this study, in patients who received UST, the proportion of CR and serum trough levels at week 8 were demonstrated to be significantly lower in the high-LRG group than those in the low-LRG group; however, those in patients who received anti-TNF did not exhibit significant differences. Since serum LRG has been reported to reflect clinical symptoms and endoscopic activity better than serum CRP24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, the current induction dose and serum trough levels at week 8 of anti-TNF were sufficient to achieve clinical remission at week 8 even in patients with higher endoscopic activities, but those of UST were not. In a randmized controlled study involving patients with CD during induction treatment, a higher dose of UST was intravenously administered (6 mg/kg at weeks 0 and 2) compared to this study. The findings demonstrated that the efficacy of UST and ADA was not significantly different in patients with higher disease activity compared to the observations in this study10. Therefore, when considering anti-cytokine biologics treatment for patients with IBD exhibiting high LRG levels, optimizing treatment effectiveness may be achievable by selecting anti-TNF treatment or increasing serum trough levels of UST through the administration of a higher dose during induction treatment.

Various studies have been conducted on factors predicting the anti-cytokine bilogics’ treatment effectiveness for patients with IBD, including clinical characteristics and serum or fecal biomarkers; however, no conclusive guideline has been established41. In recent years, mucosal gene expression levels have also received attention, and oncostatin M and interleukin-23 A have been reported as useful mucosal biomarkers for predicting the effectiveness of anti-TNF treatment and UST42,43. However, those methods require a colonoscopy, biopsy, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis, making their clinical application challenging. In contrast, serum LRG can be measured similarly as serum CRP in routine laboratory settings and can be immediately applied for clinical use.

This study had some limitations. First, the number of patients who received IFX or ADA was insufficient to allow analysis for each patient with CD and UC, and the number of patients who received GOL was too small to analyze and excluded; a larger cohort study is necessary for validating the findings of this study. Second, although this was a prospective study in a multicenter setting, confounding factors affecting the effectiveness of biologic treatment could not be entirely verified because this study did not use randomization. Third, we could not assess the usefulness of serum LRG in biologics, such as vedolizumab. Moreover, whether serum LRG could be a predictive biomarker for any other biologics is unclear. Finally, fecal calprotectin levels were not assessed in this study because they could not be performed simultaneously as serum LRG under the Japanese health insurance system.

In conclusion, the pretreatment levels of serum LRG could predict the effectiveness including serum trough levels of UST during induction treatment and assist in selecting appropriate anti-cytokine biologics in patients with IBD.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- UST:

-

Ustekinumab

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- LRG:

-

Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein

- 0w-LRG:

-

Serum LRG level at week 0

- CR:

-

Clinical remission

- SF-CR:

-

Steroid-free clinical remission

References

Ng, S. C. et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 390, 2769–2778. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0 (2017).

Nakase, H. et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease 2020. J. Gastroenterol. 56, 489–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-021-01784-1 (2021).

Chudy-Onwugaje, K. O., Christian, K. E., Farraye, F. A. & Cross, R. K. A state-of-the-art review of new and emerging therapies for the treatment of IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 25, 820–830. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izy327 (2019).

Singh, S. et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of biologic therapies for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 1002–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00312-5 (2021).

Turner, D. et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the international organization for the study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 160, 1570–1583. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031 (2021).

Murthy, S. K. et al. The 2023 impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: Treatment landscape. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 6, 97–S110. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcag/gwad015 (2023).

Hibi, T. et al. Efficacy of biologic therapies for biologic-naïve Japanese patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: a network meta-analysis. Intest. Res. 19, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2019.09146 (2021).

Singh, S., Fumery, M., Sandborn, W. J. & Murad, M. H. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: first- and second-line pharmacotherapy for moderate-severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 47, 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14422 (2018).

Sands, B. E. et al. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1215–1226. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1905725 (2019).

Sands, B. E. et al. Ustekinumab versus adalimumab for induction and maintenance therapy in biologic-naive patients with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3b trial. Lancet 399, 2200–2211. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00688-2 (2022).

Singh, S., Murad, M. H., Fumery, M., Dulai, P. S. & Sandborn, W. J. First- and second-line pharmacotherapies for patients with moderate to severely active ulcerative colitis: an updated network meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 2179–2191.e2176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2020.01.008 (2020).

Bokemeyer, B. et al. Real-world effectiveness of vedolizumab compared to anti-TNF agents in biologic-naïve patients with ulcerative colitis: a two-year propensity-score-adjusted analysis from the prospective, observational VEDO. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 58, 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.17616 (2023).

Ko, Y., Paramsothy, S., Yau, Y. & Leong, R. W. Superior treatment persistence with ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease and vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis compared with anti-TNF biological agents: real-world registry data from the persistence Australian National IBD Cohort (PANIC) study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 54, 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.16436 (2021).

Feuerstein, J. D. et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 158, 1450–1461. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.006 (2020).

Feuerstein, J. D. et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 160, 2496–2508. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.022 (2021).

Torres, J. et al. ECCO Guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: Medical treatment. J. Crohns Colitis 14, 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz180 (2020).

Raine, T. et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J. Crohns Colitis 16, 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab178 (2022).

Vande Casteele, N. et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 148, 1320–1329e1323. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.031 (2015).

Vasudevan, A. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: the association between serum ustekinumab trough concentrations and treatment response in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izad065 (2023).

Yoshihara, T. et al. Tissue drug concentrations of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents are associated with the long-term outcome of patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 23, 2172–2179. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000001260 (2017).

Takenaka, K. et al. Higher concentrations of cytokine blockers are needed to obtain small bowel mucosal healing during maintenance therapy in Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 54, 1052–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.16551 (2021).

Takenaka, K. et al. Transmural remission characterized by high biologic concentrations demonstrates better prognosis in Crohn’s disease. J. Crohns Colitis 17, 855–862. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac185 (2022).

Haupt, H. & Baudner, S. [Isolation and characterization of an unknown, leucine-rich 3.1-S-alpha2-glycoprotein from human serum (author’s transl)]. Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 358, 639–646 (1977).

Shinzaki, S. et al. Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein is a serum biomarker of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 11, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw132 (2017).

Shimoyama, T., Yamamoto, T., Yoshiyama, S., Nishikawa, R. & Umegae, S. Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein is a reliable serum biomarker for evaluating clinical and endoscopic disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izac230 (2022).

Takenaka, K. et al. Serum leucine-rich α2 glycoprotein: a novel biomarker for transmural inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 118, 1028–1035. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002127 (2022).

Kawamura, T. et al. Accuracy of serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein in evaluating endoscopic disease activity in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 29 https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izac076 (2023).

Yasutomi, E. et al. Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein as a marker of mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease. Sci. Rep. 11, 11086. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90441-x (2021).

Kawamoto, A. et al. Combination of leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein and fecal markers detect Crohn’s disease activity confirmed by balloon-assisted enteroscopy. Intest. Res. https://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2023.00092 (2023).

Horiuchi, I., Horiuchi, K., Horiuchi, A. & Umemura, T. Serum leucine-rich α2 glycoprotein could be a useful biomarker to differentiate patients with normal colonic mucosa from those with inflammatory bowel disease or other forms of colitis. J. Clin. Med. 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13102957 (2024).

Yoshida, T. et al. Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 glycoprotein in monitoring disease activity and intestinal stenosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 257, 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.2022.J042 (2022).

Shinzaki, S. et al. Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein is a potential biomarker to monitor disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease receiving adalimumab: PLANET study. J. Gastroenterol. 56, 560–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-021-01793-0 (2021).

Yanai, S. et al. Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein may be predictive of the adalimumab trough level and antidrug antibody development for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a sub-analysis of the PLANET study. Digestion 102, 929–937. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517339 (2021).

Lewis, J. D. et al. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 14, 1660–1666. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.20520 (2008).

Summers, R. W. et al. National cooperative Crohn’s disease study: results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology 77, 847–869 (1979).

Mary, J. Y. & Modigliani, R. Development and validation of an endoscopic index of the severity for Crohn’s disease: a prospective multicentre study. Groupe d’Etudes Thérapeutiques Des affections inflammatoires Du Tube Digestif (GETAID). Gut 30, 983–989. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.30.7.983 (1989).

Sturm, A. et al. ECCO-ESGAR guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD Part 2: IBD scores and general principles and technical aspects. J. Crohns Colitis 13, 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy114 (2019).

Iwamoto, N. et al. Selective detection of complementarity-determining regions of monoclonal antibody by limiting protease access to the substrate: nano-surface and molecular-orientation limited proteolysis. Analyst 139, 576–580. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3an02104a (2014).

Iwamoto, N. et al. Verification between original and biosimilar therapeutic antibody infliximab using nSMOL coupled LC-MS bioanalysis in human serum. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 19, 495–505. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389201019666180703093517 (2018).

Iwamoto, N. et al. Multiplexed monitoring of therapeutic antibodies for inflammatory diseases using Fab-selective proteolysis nSMOL coupled with LC-MS. J. Immunol. Methods 472, 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2019.06.014 (2019).

Gisbert, J. P. & Chaparro, M. Predictors of primary response to biologic treatment [Anti-TNF, Vedolizumab, and Ustekinumab] in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: from basic science to clinical practice. J. Crohns Colitis 14, 694–709. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz195 (2020).

West, N. R. et al. Oncostatin M drives intestinal inflammation and predicts response to tumor necrosis factor-neutralizing therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Med. 23, 579–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4307 (2017).

Nishioka, K. et al. Mucosal IL23A expression predicts the response to ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastroenterol. 56, 976–987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-021-01819-7 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sho Masui (Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Kyoto University Hospital, Kyoto, Japan, and Division of Integrative Clinical Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan) for measuring the serum trough levels of UST, IFX, and ADA, and Takashi Shimada and Kotoko Yokoyama (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan) for their support in measuring the serum trough concentrations. The authors also thank Hiroyuki Kurakami (Department of Clinical Research Center, Nara Medical University Hospital, Kashihara, Nara, Japan) for supporting the data analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI) grant number 22K15965. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TA and TaYo contributed equally. Conceptualization: TA, TaYo, SS, TomYa, TK, HI. Data curation: TA, TaYo, SS. Formal analysis: TA, TaYo, SS. Funding acquisition: TA, TaYo, SS. Investigation: TA, TaYo, SS, YS, TaYa, NO, SH, YM, KN, HO, TosYa, YA, IK, SK, SE, TK, MaK, YuT, AA, TaT, MT, YOK, RU, MiK, YoT, TI, AY, HI. Methodology: TA, TaYo, SS, TomYa, TK, HI. Project administration: TA, TaYo, SS. Resources: TA, TaYo, SS, AY. Software: TA. Supervision: HI, YH, TeT. Validation: TA, TaYo, SS. Visualization: TA, TaYo, SS. Writing - original draft: TA. Writing - review & editing: TaYo, SS, YS, TaYa, NO, SH, YM, KN, HO, TosYa, YA, IK, SK, SE, TK, MaK, YuT, AA, TaT, MT, YOK, RU, MiK, YoT, TI, AY, HI, YH, TeT. Approval of final manuscript: all authors: TA, TaYo, SS, YS, TaYa, NO, SH, YM, KN, HO, TosYa, YA, IK, SK, SE, TK, MaK, YuT, AA, TaT, MT, YOK, RU, MiK, YoT, TI, AY, HI, YH, TeT.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S. Shinzaki received lecture fees from Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, and lecture fees and grants from AbbVie GK, Sekisui Medical Co., Ltd.; A. Yonezawa: grants from Shimadzu Corporation and Ayumi Pharma Corporation.; H. Iijima: lecture fees from AbbVie GK and Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma Corporation; T. Takehara: grants from Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma Corporation, and lecture fees and grants from AbbVie GK. None of the aforementioned are related to this study. The remaining authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclosure.

Ethnics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the ethics committee of Osaka University Hospital, the ethics committee of National Hospital Organization Osaka National Hospital, the ethics committee of Osaka Rosai Hospital, the ethics committee of Toyonaka Municipal Hospital, the ethics committee of Japan Community Healthcare Organization Osaka Hospital, the ethics committee of Itami City Hospital, the ethics committee of Suita Municipal Hospital, the ethics committee of Ikeda Municipal Hospital, the ethics committee of Otemae Hospital, the ethics committee of Kansai Rosai Hospital, the ethics committee of Higashiosaka City Medical Center, the ethics committee of Osaka General Medical Center, the ethics committee of Osaka Police Hospital, the ethics committee of Yao Municipal Hospital and the ethics committee of Hyogo Prefectural Nishinomiya Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amano, T., Yoshihara, T., Shinzaki, S. et al. Selection of anti-cytokine biologics by pretreatment levels of serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Rep 14, 29755 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80285-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80285-6