Abstract

Developing novel materials is an essential requirement in the engineering field. This study investigates the effects of incorporating wood dust particles on the mechanical and erosive wear properties of Luffa acutangula fiber (LAF)-reinforced phenol-formaldehyde composites, fabricated using the hand layup method with a constant 20% fiber content and varying wood dust particle contents of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%. Using the Taguchi method, the study identifies the optimal combination for minimizing erosive wear − 20% wood dust content, 45 m/s impact velocity, 60° impingement angle, 600 μm erodent size, and 60 mm standoff distance—achieving a minimum erosion rate of 189.8 mg/kg. The addition of 20% wood dust results in significant enhancements in mechanical properties, with tensile strength increasing by 17.56%, flexural strength by 48.78%, and impact strength by 54.64%, compared to composites without wood dust. These findings underscore the potential of LAF composites with bio-fillers for lightweight structural applications in sectors prioritizing sustainability and mechanical durability, such as automotive and aerospace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural fibers are rapidly replacing synthetic fibers in industrial and structural applications due to their environmental benefits, cost-effectiveness, and mechanical properties1,2. The development of materials using natural fibers is creating more interest among researchers owing to their potential. The cellulose-rich content in the fibers improves the mechanical performances of the materials3,4. The polymer materials used are widely used in many plastic industries for making engineering products. Phenol-formaldehyde polymers are widely valued in composite materials for their thermal stability and mechanical robustness, making them a popular matrix choice. The inclusion of natural fibers such as coir, sisal, and jute into these polymers further enhances the composites’ mechanical properties, including tensile strength and durability, due to the fibers’ inherent cellulose content. Additionally, bio-fillers like wood dust and rice husk offer not only mechanical reinforcement but also environmental benefits, contributing to sustainable material development by promoting biodegradability and reducing overall waste5,6,7. However, it has limitations for applications because of the brittleness and susceptibility to wear8,9. To strengthen the mechanical characters of polymers, natural fibers such as coir, sisal, hemp, flax, palm, and jute have been reinforced into the polymers10,11. The natural plant fiber reinforcement in the polymer offers positive environmental welfare with respect to utilization of waste materials, disposability, and degradability12,13,14. However, natural fiber-reinforced composites often face challenges, such as brittleness and susceptibility to wear, which can be mitigated by incorporating biofillers. Biofillers, such as wood dust, rice husk, and other lignocellulosic materials, not only enhance the mechanical and thermal properties of composites but also contribute to sustainable material development15. Among these natural fibers, Luffa acutangula, commonly known as ridge gourd fiber, has gained attention for its potential in reinforcing polymer composites16,17,18,19. The hybridization of sisal, ridge gourd, and coconut spathe fibers with epoxy resin exhibits higher tensile performance, and also ridge gourd-sisal hybridization has a 65% greater tensile value than other composites20,21,22. Chemically treated sponge gourd fibers have 10–35% increased compressive strength and good tensile properties23,24. Normally the natural fiber (plant fiber) particles, such as coir particles and wood dust particles, are dumped into the environment after use as waste. Since they are plant fibers, they are rich in cellulose content and other chemical contents like plant fibers. The inclusion of natural fiber-filled composites enhances their mechanical performances25,26,27. Research indicates that the inclusion of biofillers can significantly improve the mechanical properties of natural fiber composites. For instance, the addition of wood dust particles into polymer matrices enhances tensile strength, flexural modulus, and impact resistance28,29,30,31. Similarly, the introduction of coir particles into phenol-formaldehyde composites has been shown to improve wear resistance and mechanical performance32. Recent studies highlight the growing interest in using biofillers like wood dust and cellulose-rich particles in natural fiber composites for various industrial applications. These biofillers not only utilize waste materials but also offer environmental advantages such as biodegradability and low carbon footprint, making them ideal for eco-friendly composites. Fillers like wood dust play a crucial role in enhancing fiber-reinforced composites by improving mechanical properties, such as tensile strength, impact resistance, and matrix dispersion, while also reducing void content. Wood dust, being a lignocellulosic material, provides natural bonding with polymer matrices, which aids in mechanical reinforcement and reduces material brittleness.

Despite the growing body of research on natural fibers, limited work has been done on Luffa acutangula fiber in phenol-formaldehyde polymer composites. The present study aims to bridge this gap by investigating the mechanical and erosive wear characteristics of Luffa acutangulafiber composites reinforced with wood dust particles33,34. The dried inner core of the Luffa cylindrica fruit has a unique structure, resembling a 3-dimensional, natural fibrous mat. Unlike other natural fibers, such as sisal and banana fibers, Luffa cylindrica features a thick outer peel surrounding the fruit, while the interior is composed of a sponge-like gourd35. The Taguchi method is a robust statistical tool used for optimizing process parameters to achieve high performance with minimal experimental trials. This methodology is particularly effective in analyzing wear characteristics of composite materials, as it systematically evaluates the influence of multiple factors simultaneously. Previous studies have successfully applied the Taguchi method to optimize mechanical properties and wear resistance in natural fiber composites. For example, studies on coir and jute-reinforced composites have used Taguchi analysis to optimize tensile strength and erosion resistance36,37,38,39,40. In this study, the Taguchi L27 orthogonal array design was employed to determine the optimal process parameters for minimizing erosive wear in Luffa acutangula fiber-reinforced composites. The parameters studied include wood dust content, impact velocity, impingement angle, erodent size, and standoff distance. By using this experimental design, the total number of experiments was reduced from 243 to 27, allowing for efficient analysis without compromising the accuracy of the results. This method’s systematic approach, combined with the analysis of signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios, makes it ideal for wear characterization in composite materials.

The development of sustainable and environmentally friendly materials has become a global priority due to the increasing demand for green technologies and the reduction of plastic waste. The use of natural fibers and biofillers in polymer composites offers a viable solution to these global challenges. Composites reinforced with renewable resources such as Luffa acutangula and wood dust not only provide comparable mechanical and thermal properties to synthetic materials but also offer significant environmental benefits. Although natural fibers have gained prominence due to their eco-friendliness and cost-effectiveness, the use of Luffa acutangula fiber in polymer composites remains underexplored. Additionally, the integration of wood dust particles presents challenges, including uniform dispersion and interface adhesion. Current research lacks comprehensive insight into optimizing such composites using statistical methods. The Taguchi method, which facilitates the optimization of multiple parameters with minimal experimental trials, is crucial for evaluating wear behavior, making this study both necessary and timely. The present study contributes to this global effort by developing a novel bio-composite that leverages waste materials like wood dust to enhance the performance of natural fibers in phenol-formaldehyde polymer matrices. Such bio-composites can find applications in various industries, including automotive, aerospace, and construction, where sustainable materials are increasingly in demand. This work aligns with the global movement towards the circular economy, where waste materials are repurposed to create high-performance engineering products.

Materials and methods

Materials

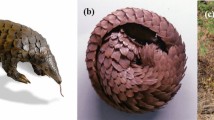

The materials shown in Fig. 1 used for the fabrication of composite specimens. Luffa acutangula fibers extracted from the fruit of ridge gourd from India Mart. The wood dust particles are collected from Kumar woods.

in Karaikudi, Tamil Nadu, India and sieved to an average size of 800 microns. We obtained resole Phenol Formaldehyde liquid resin, along with divinylbenzene (cross linking agent) and hydrochloric acid (acidic catalyst), from the shop POOJA Chemicals located in Madurai, Tamil Nadu State, India.

Preparation of composite samples

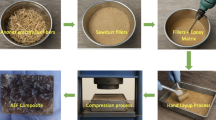

To make the composite plates made of wood-dust-filled Lufa acutangula fiber-reinforced composites, we preferred the hand lay-up method and used a mold cavity with 150 mm × 150 mm × 3 mm dimensions. The hand lay-up method was chosen for its simplicity and effectiveness in maintaining fiber alignment, allowing for consistent fabrication across samples. We fabricated composites using four different concentrations of wood dust particles: 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% mass fractions. The wood dust particle weight percentages of 10%, 20%, and 30% were chosen based on previous studies that demonstrated optimal reinforcement effects at these levels. Additionally, initial experimental trials indicated that this range offers a balance between mechanical property enhancement and manufacturability. The quantity of fiber layer (FL) was kept constant at 20% mass fraction, while we hybridized four different quantities of wood dust particles (0–30% mass fractions), resulting in composites with the designations 20FL/0WD, 20FL/10WD, 20FL/20WD, and 20FL/30WD given in Table 1. The process flow of experimentation shown in Fig. 2.

For removing the moisture content, the WD particles were exposed to sunlight for 12 h prior to the process. We mixed the phenol formaldehyde resin with the WD particles at room temperature for 30 min using a mechanical stirrer and then added the cross-linking agent and acidic catalyst, mixing the solution again with the mechanical stirrer for 15 min. Then the 20% of fiber is placed in the mold cavity as a layer. Then the mixture of resin and wood particles was poured over the fiber layer into the mold cavity and allowed the setup to cure for 24 h at room temperature.

Testing of samples

The test samples underwent mechanical testing, including tensile, flexural, and impact tests, to determine their physical properties. The tensile experiment was conducted in the machine FIE-UTE 40 HGFL (universal testing machine) as per the international standard ASTM D638-10. Similarly, as per the ASTM D790-10 standard, flexural tests were performed in the above-mentioned machine. Meanwhile, impact testing was carried out on the test samples as per ISO 180 using an Izod impact machine. All tests were done under standard room environmental temperature and ambient pressure conditions to maintain the test results’ consistency. In this study, three samples were tested for each mechanical test, ensuring data consistency and reliability. The allowable error margin for all tests was maintained at ± 5% in accordance with ASTM standards.

Density

Density The density and void content of the samples were calculated. Theoretical density was determined using the rule of mixtures, while experimental density was obtained by measuring the mass and volume of each composite sample. The void content was calculated using the formula:

Erosion test

Experimental set up for Erosion Test34.

Erosion Tests were carried out on composite specimens composed of FL/WD/PF to measure their erosive properties, using an erosion-test apparatus illustrated in Figure 3. The apparatus included several components, such as the erodent feeder nozzle, erodent feeder box, nozzle of the mixing chamber, mixing chamber, sample holder, air-flow vent, and erodent collector. The erodent (dry silica sand) of three dissimilar sizes (200, 400, and 600 μm) was utilized during the test. Followed by the test, the samples were extracted from the experiment setup and cleaned using acetone to remove any residual erodent or contaminants.

After being cleaned with acetone, the composite test samples were dried and accurately weighed up using a digital balance with a precision of ± 0.1 mg. The weightiness of the samples was measured before the test (erosion) and after the test to calculate the loss of weight. The loss of weight was noted and used to determine the rate of erosion, which is calculated by dividing the loss of weight of test samples by the eroding particle’s weight. The test was repetitive until a stable erosion rate was reached.

Taguchi experimental design

The Taguchi experimental design was used to study the erosive wear character of composite samples. It is an efficient and systematic method of approach to determine the optimum process parameter level for better performance. The orthogonal array was constructed to reduce the experiment trails (numbers), and the orthogonal array offers well-balanced experiment sets. In order to optimize the parameters, the S/N ratio (signal to nose) serves as the objective function and helps with the analysis of results.

The S/N (signal-nose) ratios used to optimize the static problems are: the nominal-the-better, the smaller-the-better, and the larger-the-better ratio. The minimum erosive rate and the optimum parameters come in the smaller—the—better characteristics. To detect the erosive performance of the FL/WD/PF composite, this study utilizes five process constraints (parameters) at three different levels. The process parameters for the Taguchi analysis were selected based on their influence on wear and mechanical properties, specifically particle size, impact velocity, and reinforcement percentages. The selection of Taguchi parameters (wood dust content, impact velocity, impingement angle, erodent size, and standoff distance) was based on preliminary experiments and existing literature, which emphasize the relevance of these parameters in controlling mechanical and wear characteristics.

By traditional methods, the experimental design would require 243 experiments; by the use of the Taguchi technique, it has been reduced to just 27 experiments. The L27 orthogonal array was selected due to its ability to handle three factors at three levels efficiently, allowing for comprehensive evaluation with a manageable number of experimental runs. This design minimizes the experimental workload while still providing a robust statistical analysis of the wear behavior of the composite. The erosion (wear) test of the composite is carried out with fixed parameters, including silica as the erodent, 10.0 ± 1.0 g/min as the erodent feed rate, an 80 mm nozzle length, and a 3 mm nozzle diameter. Table 2 presents the process parameters and their respective setting levels for these experiments.

Results and discussion

Effect of wood dust particles on the tensile characters of composites

The mechanical performance (tensile strength) analysis of WD/CP/PF composites was conducted and presented in Fig. 4. The test sample without WD has a tensile performance of 35.121 MPa and a modulus of 1158.4 MPa. It is understood that the Luffa acutangula fiber increases the tensile performance of the composite test samples. From the figures, there is an increasing tendency to tensile strength by the inclusion of WD particles. The inclusion of a 10% mass fraction of wood dust particles improves the tensile performance to 39.313 MPa, which is 10.66% higher. The highest (maximum) tensile performance of 46.218 MPa is recorded in the test sample, which has 20% wood dust particles, i.e., the sample 20FL/20WD. The percentage increment from the non-wood dust sample, i.e., 20FL/0WD, is 17.56%.

The improvement of tensile performance or strength due to many reasons such as : wood particles composed of cellulose which will improves the strength and stiffness, the wood dust particles contain natural adhesives such as : lignin and hemicellulose which are the binding agent between the fibers and the resin matrix and the particles may act as fillers which helps to distribute the fibers more evenly throughout the matrix and improves the homogeneity which reduce the occurrence of voids and weak spots in the material, leading to improved strength41.Again, the inclusion of 30% mass fraction of particles reduces the strength. This reduction is owing to the overloading of fibers in the composites, which reduces the compatibility and insufficient resin wettability to bind the reinforcements.

Effect of wood dust particles on the flexural performance of composites

Figure 5 demonstrates the variation of flexural performance (strength) of the composites owing to the inclusion of wood dust particles along with Luffa acutangulafiber. The sample 20FL/0WD (non-wood dust particle) has a flexural performance of 51.16 MPa and a modulus of 1237.4 MPa. The inclusion of wood dust particles in the test samples (composites) improves the flexural property of the test sample. The tendency to increase the strength is proportional to the percentage of WD content. The strength increases until the inclusion of 20% of wood dust particles (mass fraction), and further increments of particles lead to the strength reduction. The inclusion of 10% wood dust particles (mass fraction) improves the flexural (bending) strength to 60.43 MPa, which is 18.11% higher than the sample having no wood dust particles, i.e., the 20FL/0WD sample. The highest flexural (bending) strength of 76.12 MPa is achieved in the test sample (composite), which has 20% wood dust particles, i.e., the sample 20FL/20WD. It is 48.78% higher than the sample 20FL/0WD. This improvement is owing to the enhancement of interfacial bonding between the PF matrix and LA fiber and improving their dispersion, leading to better load transfer and dimensional stability. Further, the inclusion of particles of more than 20% mass fraction reduces the strength because the total fiber content in the sample exceeds 40%. The excessive fiber content in composites above 40% can cause clustering, microcracks, and reduced ductility, resulting in decreased strength. Optimal balance between LA fiber and PF matrix content is essential for maintaining maximum performance (strength) and durability. Also, the addition of lignocellulosic fillers, like wood dust, enhances the flexural properties due to improved fiber-matrix bonding42.

Effect of wood dust particles on the impact performance of composites

The effect of wood dust particles on the impact performance (strength) of Luffa acutangula fiber composites according to ISO 180 is explained in Fig. 6. The trend of the improvement and decrease of impact strength is the same as for other properties. The sample 20FL/0WD had the least strength value of 0.912 KJ/m2 in this experiment. The maximum value of 2.011 KJ/m2impact performance (strength) is achieved while adding 20% mass fraction of wood dust in the composite test samples. The sample with a 10% mass fraction of wood dust particles has 35.41% higher impact strength than the sample 20FL/0WD. As the sample, 20FL/20WD have 54.64% higher impact strength than the non-wood dust composite sample. It is clearly understood that wood dust particles boost the mechanical performance of fiber-polymer composites. The presence of lignocellulosic materials in composites increases energy absorption, thereby improving impact strength43. As with the other properties, impact strength also decreases by the inclusion of fiber content of more than 40%. The excessive fiber content in composites leads to microcracks and reduced ductility, resulting in decreased strength.

The mechanical strength of material is good at the level of 20% dust particles in all the specimens. These results align with previous studies where bio-fillers like wood dust filled fiber composites demonstrated similar tensile, flexural and impact improvements44,45,46.

Scanning electron microscopy of LAF

Figure 7 presents the scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images of untreated and compressed Luffa acutangula fiber (LAF), revealing significant differences in surface morphology and fiber alignment between the two conditions.

In the untreated fiber (left image), the surface appears relatively smooth with visible long cylindrical fibrils. The presence of natural chemical compositions like lignin, pectin, hemicellulose, and wax can be inferred from the polished appearance of the fiber, reducing its roughness. These components, particularly the lignin and wax, contribute to the smooth and somewhat hydrophobic surface, which affects fiber-matrix bonding when used in composite materials. On the other hand, the compressed fiber (right image) exhibits a rougher surface with visible surface defects and fiber delamination. Compression significantly alters the alignment of the fibrils, making the fibers appear more distorted and fractured. This deformation likely arises due to the breakdown of hemicellulose and lignin under mechanical pressure, which weakens the fiber structure and disrupts the bonding between fibrils. As a result, the fiber surface in the compressed state is more porous, enhancing mechanical interlocking when used as reinforcement in composite applications. Moreover, the images reveal a marked contrast in the structural integrity of the fibers. The normal LAF maintains a more defined cylindrical shape, while the compressed fiber shows evidence of microfibril disintegration and voids, potentially leading to reduced mechanical performance. This change in surface morphology highlights the need for chemical treatment to improve the wettability and adhesion of LAF fibers in composites, especially when combined with metallic or ceramic matrices. The SEM analysis also points to the importance of post-processing treatments in enhancing the mechanical properties of fibers. For example, the removal of surface wax and lignin via chemical treatments would expose more cellulose microfibrils, leading to a rougher surface and potentially improving the fiber-matrix interface strength.

Erosion rate - analysis

The erosive (wear) experiments accompanied on the samples of FL/WD/PF composite using the erosive wear test set up demonstrated in the Fig. 3. The process constraints (parameters) for the testing are fixed as the details given in the Table 2. Totally 27 groupings of process parameters were considered for calculating the erosive rate. The familiar software name MINITAB 23 is used for erosion analysis and optimizing the process parameters. The erosive rate for all the groupings recorded in the Table 3. From the table, it can be recognized that the least erosive rate was achieved as 189.8 mg/Kg. The groupings of process constraints (parameters) for the minimum erosion rate are 20% mass fraction of wood dust particle (level II), 45 m/s impact velocity (Level I), 60o impingement angle (Level II) 600 μm erodent size (Level III) and 60 mm stand- off distance (Level III). This combination corresponds to experiment number 10 in Table 3. This combination maintained sufficient rigidity from the wood dust while preventing excessive brittleness, allowing for effective energy absorption and reduced material loss. In contrast, higher wood dust content (30%) or increased impact velocity (60 m/s) led to suboptimal performance. Excessive wood dust increased brittleness, making the composite more prone to cracking under impact, while higher velocities intensified the erosive force, accelerating wear. Therefore, combinations deviating from the optimal balance disrupted the composite’s structural integrity, leading to reduced wear resistance. The next level of minimum erosion rate is which is achieved in the combination of 10% mass fraction of wood dust particles, 55 m/s impact velocity, 60o impingement angle, 400 μm and 60 mm stand-off distance. The difference between those erosion rates is very small. From the outcomes, it is understood that the combination of process constraints or parameters mentioned in experiment number 10 is accepted as the superior combination to achieve the least possible erosion rate. The graphical representation of process constraints affecting the erosion (wear) rate is demonstrated in Fig. 8. From the Fig. 8, it is understood that the wood dust particle content has a noteworthy influence on the erosion rate. The erosion rate increases in the test sample when the fiber quantity increases. This effect may be the growth of brittle property while increasing the fiber content. The parameters particle content and stand-off distance are the highly noteworthy parameters in erosion analysis.

Based on the ANOVA analysis, the impact velocity has a significant influence on the erosion (wear) rate. However, the impingement angle and erodent size have minimal influence, as indicated by their high p-values (0.925 and 0.420, respectively). The erosion rate observed in this study is consistent with the trends seen in other natural fiber-reinforced composites, such as those incorporating sisal and jute fibers. However, the incorporation of Luffa acutangula fiber showed a slightly higher erosion resistance compared to sisal-based composites reported researchers which can be attributed to the unique surface morphology of Luffa fibers, enhancing their interaction with the matrix.

Figure 9 shows the surface plots (3D) of the erosion rate with significant process parameters A and E. from the analysis, it is flawless that the wood dust particle content and stand-off distance have a significant impact on the erosion rate. Overall, it is decided that the grouping of process parameters, particle content (Level II), impact velocity (Level I), impingement angle (Level II) erodent size (Level III) and stand- off distance (Level III) are accepted as the paramount combination for less erosion rate on FL/WD/PF composites.

Analysis of variance for erosion rate

Table 4 displays the details of the contributions of each parameter towards the erosion (wear) rate of FL/WD/PF composites. The ANOVA method is used for finding the contribution of process parameters to the erosion (wear) rate. The F-value indicates the ratio of variation explained by each parameter relative to unexplained variation, with higher values suggesting that the parameter significantly impacts the erosion rate. The p-value shows the probability that an observed effect is due to chance; a lower p-value (typically < 0.05) means the effect is statistically significant. Together, these values highlight which parameters, such as wood dust content and impact velocity, strongly influence the composite’s wear performance, confirming their importance in achieving optimal results. To enhance the statistical understanding of the parameter influences, an ANOVA analysis was performed with 95% confidence intervals to determine the significance of each parameter. This analysis shows that wood dust particle content, stand-off distance, and impact velocity are the most significant factors affecting erosion rate, with p-values of 0.000, 0.011, and 0.022, respectively. On the other hand, impingement angle and erodent size have minimal influence, as indicated by their high p-values of 0.925 and 0.420. The confidence intervals for these parameters further confirm the range of expected erosion rates for different combinations.

In addition, an interaction analysis was conducted to assess how combinations of parameters affect the erosion rate. For example, the interaction between wood dust particle content and stand-off distance had a pronounced effect, as depicted in Fig. 9. This interaction highlights the complex relationship between process parameters, suggesting that certain combinations can either amplify or mitigate erosion, which aligns with findings in related literature47,48,49,50.

The p value shows the noteworthy process parameters and their impacts on the erosion rate. The least value of p is considered as the highly significant parameter for the erosion rate. From the table, it is understood that the contribution of wood dust particle content in the composite sample is highly significant and the ‘p’ value gotten from the analysis 0.000. As like as stand-off distance p value 0.011 which is also comparatively high. Stand-off distance is also a very significant factor in the erosion rate. Impact velocity p value 0.022, is also a significant parameter. The p values of erodent size and Impingement angle are 0.420 and 0.925 which makes a least impact on the erosion (wear) rate. The ANOVA results reveal that the wood dust particle content, stand-off distance, and impact velocity are the most significant factors affecting the erosion rate, with p-values of 0.000, 0.011, and 0.022, respectively. In contrast, the impingement angle and erodent size show minimal influence with high p-values of 0.925 and 0.420.

The rank order is wood dust particle content, stand-off distance, Impact velocity, Impingement angle, erodent size.

The Table 5 shows the S/N ratios of responses of process parameters based on their contribution to the wear rate in FL/WD/PF composites. The signal to noise that follows the smaller is the better characteristic. The contribution of particle content to the erosion in the composite plays a significant role. The Table 5 displays the rank of process parameters to obtain the least erosion based on their contribution to erosion.

Regression analysis for the process parameters

The model fit shows how well our regression equation predicts erosion rates, with a close alignment between predicted and actual values indicating a good fit. Residual plots display the differences (residuals) between observed and predicted values. Regression analysis has been done for the confirmation of a correlation between the predicted value and the experimental value. The correlation between prediction and experimentation is a good fit, which is clearly shown in the Fig. 10. The normal probability graph shows the close fit of values and the bell - shaped histogram diagram is also the evidence for the close fit of values. The coefficients for the process parameters are demonstrated in the Table 6. The erosion (wear) rate can be calculated by the equation.

From the residual graphs, it is decided that the deviation between the predicted erosion rate and the experimental data is very small. The effect of parameters A and E have high significant in the erosion rate of FL/WD/PF composites.

Conclusion

The fabrication of wood dust particle filled Luffa acutangula fiber reinforced phenol formaldehyde composites was done successfully using a hand layup method for mechanical and erosion characterization. The composite sample has 20% of wood dust particles i.e., the sample 20FL/20WD provides the maximum tensile strength of 46.218 MPa. The highest of flexural strength of 76.12 MPa is achieved in the same composite sample. The maximum value of 2.011 KJ/m2 impact strength is achieved while adding 20% mass fraction of wood dust particles in the composites. It is decided that the addition of wood dust particles to natural fiber composites enhances the mechanical performance of polymer composites. Also, it is decided that the optimum quantity of fiber content in the polymer composite is 40%. The Taguchi experimental design (L27) is the suitable method to optimize the process parameters for erosion analysis. The erosion or wear rate of composites is influenced by the process parameters, particle content, erodent size, impact velocity, standoff distance and impingement angle. The parameters of wood dust particle content, stand-off distance & impact velocity have a high influence on the erosion or wear rate. The erodent size and impingement angle have little influence on erosion rate. The minimum erosive rate of 189.8 mg/Kg achieved in the wood dust filled composite for the combination of process parameters 20% particle content, 45 m/s impact velocity, 60o impingement angle, 600 μm erodent size and 60 mm stand-off distance. The rank order is wood dust particle content, stand-off distance, Impact velocity, Impingement angle, erodent size. In summary, this study demonstrates a notable improvement in tensile (17.56%), flexural (48.78%), and impact (54.64%) strengths with 20% wood dust content. These findings underscore the potential of Luffa acutangula fiber composites with bio-fillers as sustainable materials for lightweight applications. From a practical standpoint, the composites developed in this study present significant potential for applications requiring lightweight materials with moderate erosion resistance, such as in automotive interiors, aerospace panels, and eco-friendly packaging. However, potential drawbacks include the limited long-term durability of bio-waste composites in highly erosive environments, which may restrict their use in heavy-duty applications.

Future scope

While the current study demonstrates the feasibility of using Luffa acutangula fiber and wood dust in polymer composites, further research is required to explore the incorporation of other types of bio-waste particles and natural fibers. Future studies could also investigate different fiber-matrix combinations and advanced processing techniques to enhance the composites’ mechanical properties and wear resistance, expanding their potential for high-performance applications.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Tengsuthiwat, J. et al. Lignocellulose sustainable composites from agro-waste Asparagus bean stem fiber for polymer casting applications: Effect of fiber treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 278 (3), 134884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134884 (2024).

Dhilip, J. D. J. et al. Mechanical and flammability properties of ultrasonically processed silane-treated areca-banana fiber-reinforced epoxy composites for lightweight applications. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-024-06124-w (2024).

Tengsuthiwat, J. et al. Characterization of novel natural cellulose fiber from Ficus macrocarpa bark for lightweight structural composite application and its effect on chemical treatment. Heliyon 10 (9), e30442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30442 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, L. & Zhang, X. Improving the mechanical properties of cellulose-based materials through the modification of cellulose fibers: a review. Carbohydr. Polym. 273, 118609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118609 (2022).

Feng, J. et al. Fabrication and properties of phenol-formaldehyde resin-based composite films for high-performance capacitor applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 139 (5), 51759. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.51759 (2022).

Lee, S. H., Lim, S. H. & Lee, B. H. A review on the use of natural fibers and their composites in various fields. Polymers 13 (13), 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym1313212 (2021).

Manikandan, V. & Sathiyamoorthy, D. A review on natural fiber-reinforced composite materials for eco-friendly engineering applications. Mater. Today: Proc. 45, 3377–3383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.376 (2021).

Pandey, J. K., Ahn, S. H. & Lee, C. S. Mechanical and wear properties of polymer composites: a review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 97, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2021.04.042 (2021).

Wang, Q., Ma, X. & Peng, C. Wear-resistant composite coatings based on functional polymers: a review. Coatings 11 (6), 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11060727 (2021).

Islam, M. S. & Pickering, K. L. Properties of coir fiber reinforced biodegradable polymer composites: a review. J. Polym. Environ. 29 (6), 2086–2103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-021-01963-8 (2021).

Tissera, N. D. & Siriwardhana, D. P. Tensile, flexural and impact properties of sisal fiber reinforced high-density polyethylene composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 40 (12), 476–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/07316844211003422 (2021).

Raghunathan, V. et al. Effective utilization of surface-processed/untreated Cardiospermum halicacabum agro-waste fiber for automobile brake pads and its tribological performance. Tribol. Int. 197, 109776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2024.109776 (2024).

Rasul, M. G., Akhtar, J., Ahmad, M. M. & Kamal, M. S. Effect of natural fiber reinforcement on the mechanical and thermal properties of polymer composites: a review. J. Polym. Environ. 29 (2), 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-020-01918-9 (2021).

Kannan, M. & Arunachalam, V. P. A review on natural fiber composites for sustainable applications: prospects and challenges. Polym. Compos. 42 (6), 2294–2313. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.25835 (2021).

Kammoun, M., Al-Maadeed, M. A. & Hassan, A. Recent advances in bio-based materials for sustainable development: a review. J. Clean. Prod. 304, 127040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127040 (2021).

Kumar, M. S. & Uthayakumar, M. Study on the mechanical properties of Luffa acutangula reinforced polymer composite for commercial applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 10, 470–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.08.044 (2021).

Ramesh, M., Dhanalakshmi, K. & Palanikumar, K. Mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy/Luffa acutangula/glass fiber hybrid composites. Polym. Bull. 78, 5303–5318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-020-03250-8 (2021).

Sankar, S., Senthilkumar, P. & Arunachalam, V. P. Investigation on mechanical and thermal properties of Luffa acutangula fiber reinforced epoxy composites. J. Polym. Environ. 28, 1742–1752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-020-01822-6 (2020).

Panneerdhass, R., Gnanavelbabu, A. & Rajkumar, K. Mechanical properties of Luffa fiber and ground nut reinforced epoxy polymer hybrid composites. Procedia Eng. 97, 2042–2051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2014.12.447 (2014).

Mohanty, S. S., Nayak, S. K. & Verma, S. K. Mechanical Properties of Natural fiber-reinforced Composites (Advanced Materials Letters, 2021).

Singh, R. K., Das, R. & Singh, A. Investigations on the Mechanical Properties of Hybrid Natural fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites (Journal of Materials Science Research, 2022).

Hemalatha, S. & Ramesha, N. Tensile properties of natural fiber-reinforced epoxy-hybrid composites. Indian J. Adv. Chem. Sci. 2, 24–27 (2014).

Varma, K. S. K., Kumar, P. & Nayak, S. K. Mechanical and water absorption properties of sponge gourd fiber-reinforced polymer composites. J. Nat. Fibers. 18 (4), 559–572 (2021).

Al-Mobarak, T., Mina, M. & Gafur, M. Material properties of sponge-gourd fiber–reinforced polylactic acid biocomposites: Effect of fiber weight ratio, chemical treatment, and treatment concentrations. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 32 (7), 967–994. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892705718772880 (2019).

Deepa, G., Dhinakaran, S. D. & Nagarajan, R. Mechanical properties of coir particles filled epoxy composites: a comprehensive review. J. Nat. Fibers. 18 (1), 1–17 (2021).

Saha, S. K., Chowdhury, S. G. & Hossain, M. A. Mechanical and thermal properties of wood dust-filled thermoplastic composites: a comprehensive review. J. Nat. Fibers. 18 (2), 155–176 (2021).

Ramesh, M. et al. Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: a review. e-Polymers 22 (1), 898–916. https://doi.org/10.1515/epoly-2022-0080 (2022).

Barik, R. K., Biswas, S. & Patra, R. C. Effect of particle size on the mechanical properties of sawdust-reinforced epoxy composites. J. Polym. Environ. 29 (3), 881–894 (2021).

Hossain, S. S., Islam, M. S. & Hossain, M. M. Investigation of tensile strength and hardness of sawdust-filled epoxy composites. J. Mater. Sci. Res. Reviews. 5 (3), 68–78 (2021).

Anwar, R. M., Bhuiyan, A. M. A. & Das, S. Mechanical properties of sawdust-filled epoxy composites: Effect of particle size. J. Polym. Mater. 38 (2), 259–273 (2021).

Israa, G. H. Study the effect of particle size on the mechanical properties of particulate natural composite materials. (2017).

Jose, A., Athijayamani, A., Ramanathan, K. & Sidhardhan, S. Effects of an addition of coir-pith particles on the mechanical properties and erosive-wear behavior of a wood-dust-particle-reinforced phenol formaldehyde composite. Materiali Tehnologije. 51, 805–811. https://doi.org/10.17222/mit.2016.284 (2017).

Saba, N., Paridah, M. T. & Jawaid, M. A review on dynamic mechanical properties of natural fibre reinforced polymer composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 36 (19), 1467–1481. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2017.1354740 (2017).

Lu, Y., Hamouda, H. & Othman, M. Mechanical, thermal, and environmental impact of bio-fillers in polymer composites. Polym. Polym. Compos. 26 (8), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/1528083718811086 (2018).

Ashok, K. G. et al. Mechanical and morphological properties of Luffa/carbon fiber-reinforced hybrid composites. Mater. Today: Proc. 33 (1), 637–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.05.716 (2020).

Sivarajan, S. S. & Syamala, S. Optimization of process parameters for wear rate of bagasse fiber reinforced epoxy composites using Taguchi method. J. Minerals Mater. Charact. Eng. 9 (1), 47–60 (2021).

Prusty, R. K. & Das, P. R. Investigation of wear behavior of bagasse fiber-reinforced epoxy composite using Taguchi method. Int. J. Mech. Prod. Eng. Res. Dev. 11 (2), 825–834 (2021).

James, D. J. D., Pandiyan, G. K. & Vijay, R. Chemically treated Acacia nilotica filler-reinforced epoxy composites: tribological studies and optimization of process parameters. Chem. Pap. 78, 7395–7407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-024-03601-4 (2024).

Suryawanshi, S. M. & Sutar, S. S. Optimization of wear performance of bagasse fiber-reinforced epoxy composites using Taguchi method. Mater. Today: Proc. 42, 347–353 (2021).

Raghavendra, G., Acharya, S. K., Deo, C. R. & Mishra, P. Fabrication-modelling and analysis on tribological performance of natural composites using Taguchi approach. Procedia Eng. 38, 2635–2644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.06.310 (2012).

Shejkar, S. K., Agrawal, B., Agrawal, A., Gupta, G. & Pati, P. R. Influence of filler content and surface modification on physical and mechanical properties of epoxy/walnut shell particulate composites. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 37 (7), 1215–1232. https://doi.org/10.1080/01694243.2022.2066915 (2022).

Zarna, C., Opedal, M. T., Echtermeyer, A. T. & Chinga-Carrasco, G. Reinforcement ability of lignocellulosic components in biocomposites and their 3D printed applications: a review. Compos. Part. C: Open. Access. 6, 100171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomc.2021.100171 (2021).

Hasan, A., Rabbi, M. S. & Billah, M. M. Making the lignocellulosic fibers chemically compatible for composite: a comprehensive review. Clean. Mater. 4, 100078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clema.2022.100078 (2022).

Krishnudu, D. M., Sreeramulu, D. & Ramesh, N. Synthesis, characterization, and properties of epoxy filled Luffa cylindrica reinforced composites. Materials Today: Proceedings, 5(2), 3835–3841. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2017.11.637

Tamilmani, G. K. & Pawar, S. Development and characterization of sisal fiber and wood dust-reinforced polymeric composites. J. Nat. Fibers. https://doi.org/10.1080/15440478.2019.1710649 (2020).

Haque, M. & Islam, M. Effect of wood saw dust and chopped jute fiber on the tensile properties of epoxy-based polymer composite. Chem. Eng. Res. Bull. 22 (1), 94–98. https://doi.org/10.3329/cerb.v22i1.54306 (2021).

Ramesh, M. & Panneerselvam, K. Mechanical investigation and optimization of parameter selection for nylon material processed by FDM. Materials Today: Proceedings, 46(19), 9303–9307. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.697

Ramesh, M. & Panneerselvam, K. PLA-based material design and investigation of its properties by FDM. In Advances in Additive Manufacturing and Joining (229–241). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9433-2_20 (2019).

James, D. J. D., Mohan, R. & Vijay, R. Effect of stacking sequence on tribological properties of bamboo/jute-reinforced hybrid epoxy polymer composites. Mater. Today: Proc. 39 (1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.04.809 (2021).

James, D. J. D., Ramesh, M., Ranjithkumar, M. & Chandran, M. Optimization of machining parameters of aluminum metal matrix composites using Taguchi based desirability function analysis. Materials Today: Proceedings, 69(3), 779–782. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.07.206

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AHL-Writing and Reviewing the article SJA- Writing the articleNMB- Reviewing the revisionSPJ-Data Analysis and Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

A, H., Arul, S.J., Basavaraj, N.M. et al. Influence of bio fillers on the characteristics of Luffa acutangula fiber reinforced polymer composites and parametric optimization using Taguchi technique. Sci Rep 14, 30730 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80316-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80316-2