Abstract

Driving pressure (DP) is a marker of severity of lung injury in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and has a strong association with outcome. However, it is uncertain whether limiting DP can reduce the mortality of patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF). Therefore, this study aimed to determine the correlation between the initial DP setting and the clinical outcomes of patients with AHRF upon their initial admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). The Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database was used to search the data of patients with AHRF, with 180-day mortality representing the primary outcome. Multiple regression analysis was subsequently performed to evaluate the initial DP and 180-day mortality association. The reliability of the results was validated using restricted cubic splines and interaction studies. This study retrospectively analyzed data from 907 patients—581 (64.06%) in the survival group and 326 (35.94%) in the nonsurvival group (NSG)—who were followed up 180 days after admission. The results revealed that an elevated initial DP was significantly correlated with 180-day mortality (HR 1.071 (95% CI 1.040, 1.102)), especially when the initial DP exceeded 12 cmH2O. AHRF patients with an initial DP > 12 cmH2O had significantly greater mortality at 28 days (p = 0.0082), 90 days (p = 0.0083), and 180 days (p = 0.0039) than those with an initial DP ≤ 12 cmH2O. Among severe patients with AHRF, 180-day mortality was significantly greater in the group with an initial DP > 12 cmH2O than in the group with an initial DP ≤ 12 cmH2O (p = 0.029). The hospital length of stay (LOS) for patients with an initial DP < 12 cmH2O was significantly longer than that for those with an initial DP > 12 cmH2O (p = 0.029). Among patients with AHRF and an initial DP > 12 cmH2O, the survival group had a significantly longer LOS in the ICU than the NSG (p = 0.00026). The initial DP settings were correlated with 180-day mortality among patients with AHRF admitted to the ICU. Particularly for patients with AHRF, it is crucial to consider implementing early restrictive DP ventilation as a potential means to mitigate mortality, and close monitoring is essential to evaluate its impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF) represents a significant clinical challenge characterized by inadequate blood oxygenation and impaired carbon dioxide elimination, often requiring mechanical ventilation (MV) to sustain gas exchange in critically ill patients1. Within this context, the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a severe manifestation of AHRF, has been a major focus of research aimed at optimizing MV strategies to minimize ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI)2. One of the key parameters in this effort is driving pressure (DP), which has been consistently associated with outcomes in patients with ARDS3.

Driving Pressure in ARDS: ARDS treatment has evolved significantly, particularly with the recognition that lung-protective ventilation strategies, focusing on limiting tidal volume and plateau pressure, can reduce mortality4. More recently, DP—the difference between plateau pressure and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)—has emerged as a reliable predictor of VILI and mortality5. Studies such as those conducted by Amato et al. have shown that an elevated DP is a strong predictor of mortality in ARDS, regardless of the tidal volume used6. Furthermore, data from randomized controlled trials indicate that targeting lower DP can lead to improved survival in ARDS patients7,8.

Broader Implications of DP in AHRF: Despite these advancements, there is a substantial gap in understanding the role of DP in a broader AHRF population that extends beyond ARDS. Unlike ARDS, AHRF encompasses a more heterogeneous group of patients with varying underlying etiologies, making it challenging to directly apply findings from ARDS studies9. Although some observational studies have suggested that DP might be a relevant predictor of outcomes in non-ARDS respiratory failure, these findings are not consistent, and there remains a paucity of large-scale investigations focused specifically on AHRF10,11.

The Need for Comprehensive Evidence: Zaidi et al. underscored the importance of conducting large-scale clinical studies to better define the utilization of DP in mechanically ventilated patients without ARDS12. Moreover, Roca et al. demonstrated that DP is a significant risk factor for ARDS development in patients initially ventilated without this condition, further highlighting the need to evaluate DP’s impact across different respiratory failure syndromes13. However, the application of these findings to non-ARDS AHRF patients remains largely unexamined, and the optimal DP threshold for this broader group is unknown14.

Rationale for the Study: To address this knowledge gap, our study aims to evaluate the impact of initial DP settings on clinical outcomes in patients with AHRF admitted to the ICU, utilizing data from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database. Specifically, we seek to determine whether the associations between elevated DP and increased mortality observed in ARDS can be extended to patients with AHRF. By exploring the correlation between initial DP and outcomes such as 180-day mortality, ICU length of stay (LOS), and hospital LOS, we aim to inform MV strategies that could potentially benefit a wider range of critically ill patients.

Significance of the Study: Our investigation aims to bridge the gap in knowledge regarding the broader application of DP management by employing a retrospective cohort design with a large, heterogeneous population. Findings from this study could provide a stronger evidence base for clinicians managing AHRF, ultimately guiding DP optimization and improving patient outcomes in settings where ARDS-specific strategies may not directly apply.

Materials and methods

This study utilized a retrospective cohort design, examining patients admitted to the ICU and included in the MIMIC-IV (version 2.2) database. The database was sourced from the multiparametric intelligent monitoring data gathered at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre (BIDMC; Boston, Massachusetts). The database contains detailed data on 73,181 hospitalized ICU patients from 2008 to 2019 (https://doi.org/10.13026/dp1f-ex47). This database was generated and maintained by the Laboratory for Computational Physiology (LCP) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), with funding from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We obtained the necessary permissions and ethical approval to utilize the MIMIC-IV database for our research (Certification No. 49670168). The use of the database was approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and the need for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants

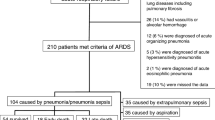

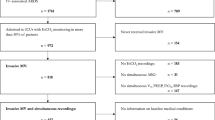

The study included ICU patients previously diagnosed with ARF/ARDS in the MIMIC-IV database. The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) patients with a diagnostic ranking above 3 for ARF/ARDS, identified using the International Classification of Diseases 9th /10th Edition (ICD-9/ICD-10) codes documented in the MIMIC-IV dataset; (2) patients with a minimum PaO2/FiO2 (P/F) ratios ≥ 300 mmHg during their ICU stay; (3) patients who received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) treatment; (4) patients with missing data on plateau pressure and end-expiratory positive pressure (PEEP) within the first 24 h following ICU admission; (5) patients with an initial DP below 0 cmH2O (the measurement of initial DP for included patients was conducted within 24 h of ICU admission). Furthermore, only the initial ICU stay was considered for patients with multiple ICU admissions. Following a 180-day follow-up period, patients who died within this timeframe were allocated to the nonsurvival group (NSG), and those who survived beyond 180 days were assigned to the survival group.

Data collection

The baseline characteristics were obtained by applying structured query language, which included age, sex, race, laboratory data, disease severity as defined by the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, the simplified Acute Physiology Scale II (SAPS II), and the Charlson comorbidity index. Comorbidities, such as myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, renal disease, and severe liver disease, were obtained for analysis using the reported ICD-9/ICD-10 codes in the MIMIC-IV database. Upon admission to the ICU, laboratory variables, including the initial levels of creatinine and albumin, white blood cell (WBC) count, lactate (Lac), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels, were assessed. The lowest P/F ratio on the day of admission was selected. The initial plateau pressure and PEEP were also recorded. This study calculated the initial DP by subtracting the initial PEEP from the initial plateau pressure.

Outcomes

Herein, we aimed to evaluate the correlation between the initial DP and 180-day mortality. Secondary outcomes were also examined, such as mortality at 28 and 90 days and 180-day mortality stratified by P/F ratio, ICU LOS, hospital LOS, and MV time.

Statistical analysis

The values for continuous variables are presented as the means (standard deviations) or medians (interquartile ranges [IQRs]). Categorical variables are represented as total numbers and corresponding percentages. For group comparisons, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, while the Student’s t-test or the Mann‒Whitney U test was used for continuous variables, as appropriate. Our study utilized multivariate regression to analyze and describe the initial DP and primary outcome associations. Baseline variables that were deemed clinically relevant or had a univariate association with the primary outcome, encompassing age, race, initial laboratory variables (BUN, WBC count, and Lac), initial SOFA score, myocardial infarct, cerebrovascular disease, severe liver disease, and sex, were included as covariates in a multivariate logistic regression model. The primary outcome analysis was duplicated after multiple imputations to avoid bias resulting from incomplete data.

A model was established to examine the correlation between the initial DP and 180-day mortality through the restricted cubic spline regression method. The study employed the DP median as the benchmark value and placed knots at the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles. Subsequently, this study used an interaction test to compare odds ratios (ORs) across the analyzed subgroups.

The patients were categorized into two groups according to their initial DP values: a group with a DP > 12 cmH2O and a group with a DP ≤ 12 cmH2O (12 cmH2O is the DP median of the population). K‒M graphs were generated to depict survival probability from inclusion to days 28, 90, and 180 and were subsequently compared across groups via the log-rank test. Furthermore, the Wilcoxon test was used to compare the two groups’ hospital LOS, ICU LOS, and ventilation time. To comprehensively examine the correlation between initial DP and 180-day mortality across various P/F ratios, the patients were categorized into two subgroups depending on their lowest P/F ratio (> 150 mmHg and ≤ 150 mmHg).

Stata 17 was used for data cleaning, merging, and preparation, while statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.2.0; R Foundation; http://www.r-project.org) and EmpowerStats (X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts; www.empowerstats.net). A significance threshold of < 0.05, with a two-sided p-value, was applied for all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics

After retrospective data analysis of 15,383 patients with ARF or ARDS, 907 met the study inclusion criteria. Figure 1 displays the flow diagram illustrating the process of patient selection. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the survival group and NSG. It reveals that the NSG had a higher mean age than the survival group. Laboratory findings showed notably elevated creatinine, WBC, and Lac levels in the NSG, while the survival group had significantly higher serum ALB levels and P/F ratios. The NSG also had higher severity scores (SOFA, SAPS II, and Charlson comorbidity index) on average. Patients with myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, or severe liver disease had an increased risk of mortality.

Additionally, the NSG had significantly higher initial plateau pressure, PEEP, and DP values. The survival group, on the other hand, had a longer average hospital LOS. No significant difference was observed between the two groups regarding ICU LOS and ventilation time.

Primary outcome

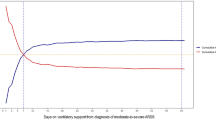

Multiple regression and restricted cubic spline analyses demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between elevated initial DP and 180-day mortality. Table 2; Fig. 2 provide the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 1.071 (95% CI 1.040, 1.102). Table S1 shows the percentage of missing data for the variables in our study. A nonlinear relationship was found, indicating that mortality increased with increasing initial DP, especially when the initial DP exceeded 12 cmH2O (Fig. 2). The results revealed non-significant interaction effects between subgroup factors and initial DPs. These findings suggested a consistent association across different subpopulations (p interaction > 0.05; Fig. 3).

Secondary outcomes

Herein, patients with AHRF were categorized into two groups according to their initial DP: the initial DP > 12 cmH2O group (high initial DP group) and the initial DP ≤ 12 cmH2O group (low initial DP group). Survival analysis revealed that patients in the high initial DP subgroup exhibited significantly greater mortality rates at 28 days (p = 0.0082), 90 days (p = 0.0083), and 180 days (p = 0.0039) than did those in the low initial DP subgroup (Fig. 4a–c).

To comprehensively investigate the correlation between the initial DP and mortality in patients with AHRF across varying P/F ratios, all patients were categorized into P/F > 150 mmHg and P/F ≤ 150 mmHg groups. A significantly greater 180-day mortality rate was observed in the P/F ≤ 150 mmHg group, specifically among patients in the high initial DP group, than in the low initial DP group (p = 0.029; Fig. 5a). Instead, the 180-day mortality rate did not significantly differ between the high- and low-initial-DP groups when the P/F ratio exceeded 150 mmHg (p = 0.2; Fig. 5b).

The additional analyses, which evaluate the impact of different DP groups and survival statuses on hospital duration, ICU stays, and ventilation times, are detailed in Fig. S1. These analyses used a stratified approach based on DP (≤ 12 cmH2O and > 12 cmH2O) and survival and mortality statuses.

Discussion

Previous research has shown a correlation between elevated DPs and less favorable outcomes in patients with ARDS6,15,16,17,18. Moreover, Oriol Roca et al.13 reported that DP is an ARDS risk factor in mechanically ventilated individuals without ARDS. However, few clinical studies have been conducted on the correlation between initial DPs and outcomes in patients with AHRF19. Our research findings substantiated the association between initial DPs and 180-day mortality in patients with AHRF hospitalized in the ICU. Herein, the interaction analysis results revealed a non-significant interaction effect between each subgroup and the initial DP. These findings validated the established association between the initial DP and 180-day mortality. The restricted cubic spline regression analysis results indicated that the initial DP had a nonlinear correlation with 180-day mortality. Specifically, the mortality rate exhibited a discernible upward trend as the initial DP increased.

Similarly, Amato et al.3 reported that the relative risk of ARDS mortality might significantly increase above a DP threshold of approximately 15 cmH2O. Claude Guérin et al.5 further corroborated this finding, demonstrating significantly higher survival rates in ARDS patients with a DP ≤ 13 cmH2O on the first day than those with a DP > 13 cmH2O. Building on these insights, Jose Dianti et al.14 proposed a lung and diaphragm protective ventilation strategy for AHRF patients with a dynamic transpulmonary DP > 15 cmH2O.

Our study extends these findings, providing evidence of a statistically significant increase in mortality among patients with AHRF when the initial DP exceeds 12 cmH2O (HR > 1). This lower threshold compared to previous studies (12 cmH2O vs. 15 cmH2O) may be attributed to several factors: (1) Advancements in ventilatory management and a deeper understanding of lung-protective strategies; (2) differences in patient populations or severity of illness across studies; (3) methodological variations, including sample size, inclusion criteria, or statistical approaches; (4) technological improvements in monitoring and measuring techniques; (5) an increased focus on personalized medicine and individualized care.

Notably, regular assessment of respiratory mechanics throughout the initial 72 h of mechanical ventilation can potentially exacerbate patient harm due to fluctuations in DP20. These fluctuations may lead to inappropriate ventilation adjustments, resulting in VILI or hemodynamic instability. A strategy incorporating lung recruitment and titrated PEEP, when compared to low PEEP, has been shown to result in a higher 28-day mortality rate for patients diagnosed with moderate to severe ARDS21. Consequently, establishing an appropriate initial DP threshold is crucial in managing patients with AHRF. This parameter is essential for facilitating protective ventilation strategies, thereby mitigating the risk of lung injury and hemodynamic instability resulting from frequent titration22.

Our findings underscore the dynamic nature of clinical research and the continuous evolution of best practices in managing severe respiratory diseases. They highlight the importance of considering lower initial DP thresholds in patients with AHRF while emphasizing the need for careful monitoring and individualized care. Future research should focus on refining these thresholds and exploring their applicability across diverse patient populations and clinical settings.

Dharani et al.23 defined severe hypoxemic respiratory failure (SHRF) as a P/F ratio < 150 mmHg. This study adhered to these diagnostic criteria and examined the correlation between initial DPs and mortality in patients who presented with SHRF or non-SHRF. The findings showed that mortality among patients with SHRF was significantly greater when the initial DP exceeded 12 cmH2O than when the initial DP was ≤ 12 cmH2O. Conversely, no significant association was found between an initial DP > 12 cmH2O and mortality in patients with non-SHRF. This phenomenon may be attributed to a diminished P/F ratio, indicating decreased lung oxygenation capacity and compliance24,25. Elevated DPs are a key factor in increasing lung strain, which can precipitate VILI. This increased strain on the lungs is strongly associated with higher mortality rates26,27,28,29. The data provide novel insights into the choice of initial ventilatory settings by considering the initial DP in patients with SHRF, underscoring the importance of minimizing lung strain to improve patient outcomes.

Based on the study, it was determined that patients with AHRF who exhibit a low initial DP (DP ≤ 12 cmH2O) experience a significantly prolonged hospital LOS, particularly in the survival group. These findings support the hypothesis that implementing a conservative DP strategy during MV could mitigate lung injury30,31,32,33. Conversely, it can prolong the hospital LOS.

Wynne Hsing Poon et al.34 reported that decreasing DPs might impact ICU LOS. Our study detected no statistically significant difference in ICU LOS between high- and low-initial-DP groups. This suggests that ICU LOS may be influenced by treatment approaches, patient well-being, and ICU resource availability rather than DP alone. Although a trend toward a longer overall hospital LOS was observed in survivors, this requires further investigation. Our findings highlight the need for additional research to understand the factors affecting hospital LOS in patients with varying DPs, especially within specific populations like those with SHRF.

Limitations

Our study has many limitations. First, the study was exclusively performed at a single center, primarily focusing on patients from the US, potentially leading to selection bias. Second, excluding patients receiving prone position ventilation was not explicitly addressed, potentially impacting the study outcomes. This selection bias arose from the absence of detailed records of prone position ventilation within the MIMIC-IV database employed in our study. Therefore, we recommend incorporating more comprehensive information on patient positioning and ventilation modalities to increase the precision and dependability of forthcoming studies. Previous research has indicated that obese patients with AHRF may require tailored parameter-setting regimens due to their distinct respiratory mechanics. However, our study did not examine the association between initial DP settings and clinical outcomes in obese patients with AHRF. To gain a thorough understanding of this patient population and offer more refined and individualized treatment options, we advocate for future research to provide particular attention to this aspect of obese patients with AHRF.

Conclusion

Our study indicates a correlation between initial DP settings and 180-day mortality in patients with AHRF hospitalized in the ICU. While our findings suggest that an initial DP setting of ≤ 12 cmH2O may be beneficial, it is crucial to approach this cautiously. Early optimization of ventilator settings and the implementation of lung-protective ventilation strategies should be prioritized to improve outcomes, particularly in patients with severe AHRF. However, the relationship between initial DP settings and the duration of hospital stay requires further investigation to fully understand its implications.

Data availability

I have deposited the data supporting this study on the Figshare platform and assigned it a publicly accessible DOI link. The following is the access information for the data; Data Access Link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25010696.

References

Lemyze, M. et al. Delayed but successful response to noninvasive ventilation in COPD patients with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 12, 1539–1547 (2017).

Clark, B. J. & Moss, M. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: dialing in the evidence? JAMA 315, 759–761 (2016).

Amato, M. B. et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 747–755 (2015).

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1301–1308 (2000).

Guérin, C. et al. Effect of driving pressure on mortality in ARDS patients during lung protective mechanical ventilation in two randomized controlled trials. Crit. Care. 20, 384 (2016).

Amato, M. B. et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 338, 347–354 (1998).

Goligher, E. C. et al. Effect of lowering Vt on mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome varies with respiratory system elastance. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 203, 1378–1385 (2021).

Urner, M. et al. Limiting dynamic driving pressure in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Crit. Care Med. 51, 861–871 (2023).

Radermacher, P., Maggiore, S. M. & Mercat, A. Fifty years of Research in ARDS. Gas exchange in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 196, 964–984 (2017).

Ketcham, S. W. et al. Causes and characteristics of death in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care. 24, 391 (2020).

Liu, K. et al. Association between the ROX index and mortality in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a retrospective cohort study. Respir. Res. 25, 143 (2024).

Zaidi, S. F. et al. Driving pressure in mechanical ventilation: a review. World J. Crit. Care Med. 13, 88385 (2024).

Roca, O. et al. Driving pressure is a risk factor for ARDS in mechanically ventilated subjects without ARDS. Respir. Care. 66, 1505–1513 (2021).

Dianti, J. et al. Strategies for lung- and diaphragm-protective ventilation in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a physiological trial. Crit. Care. 26, 259 (2022).

Estenssoro, E. et al. Incidence, clinical course, and outcome in 217 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 30, 2450–2456 (2002).

Boissier, F. et al. Prevalence and prognosis of cor pulmonale during protective ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 39, 1725–1733 (2013).

Papoutsi, E. et al. Association between driving pressure and mortality may depend on timing since onset of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 49, 363–365 (2023).

Laffey, J. G. et al. Potentially modifiable factors contributing to outcome from acute respiratory distress syndrome: the LUNG SAFE study. Intensive Care Med. 42, 1865–1876 (2016).

Liu, K.Y. et al. Association between the ROX index and mortality in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a retrospective cohort study. Respir Res. 25, 143 (2024).

Mao, J. Y. et al. Fluctuations of driving pressure during mechanical ventilation indicate elevated central venous pressure and poor outcomes. Pulm Circ. 10, 2045894020970363 (2020).

Cavalcanti, A. B. et al. Effect of lung recruitment and titrated positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) vs low PEEP on mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 318, 1335–1345 (2017).

Gattinoni, L. et al. The future of mechanical ventilation: lessons from the present and the past. Crit. Care. 21, 183 (2017).

Narendra, D. K. et al. Update in management of severe hypoxemic respiratory failure. Chest 152, 867–879 (2017).

Silva, P. L., Ball, L., Rocco, P. R. M. & Pelosi, P. Physiological and pathophysiological consequences of mechanical ventilation. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 43, 321–334 (2022).

Gattinoni, L. et al. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 1775–1786 (2006).

Terragni, P. P. et al. Tidal hyperinflation during low tidal volume ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175, 160–166 (2007).

Shen, Y. et al. Interaction between low tidal volume ventilation strategy and severity of acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care. 23, 254 (2019).

Cressoni, M. et al. Mechanical power and development of ventilator-induced lung injury. Anesthesiology 124, 1100–1108 (2016).

Chiumello, D. et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 178, 346–355 (2008).

Dreyfuss, D. & Saumon, G. Role of tidal volume, FRC, and end-inspiratory volume in the development of pulmonary edema following mechanical ventilation. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 148, 1194–1203 (1993).

Caironi, P. et al. Lung opening and closing during ventilation of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181, 578–586 (2010).

Protti, A. et al. Lung anatomy, energy load, and ventilator-induced lung injury. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 3, 34 (2015).

Brower, R. G. et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1301–1308 (2000).

Poon, W. H. et al. Prone positioning during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care. 25, 292 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PY, YZ, and SW originated and designed the study. CX and JL conducted the data gathering and cleaning. WT conducted the data analysis and interpretation. CX and YZ wrote the manuscript. CX, WT, and JL contributed equally to this work. The final manuscript was reviewed and accepted by all the writers.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, C., Tang, W., Leng, J. et al. Impacts of initial ICU driving pressure on outcomes in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a MIMIC-IV database study. Sci Rep 14, 28767 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80355-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80355-9