Abstract

To address the low utilization rate and environmental pollution of mine tailings (MT) and cement kiln dust (CKD), a CKD-based cemented paste backfill (CPB) material was prepared using quicklime (CaO) and sulfate (DH-7) as a composite alkaline activator (CAA), with CKD and slag as the cementitious material and MT as the aggregate. The optimal dosage of the new CAA was determined through unconfined compressive strength (UCS) analysis. The reaction products, pore structure, and cation dissolution ability of CKD-based CPB activated by CAA were investigated, analyzing the mechanism of strength enhancement. The results showed that the CAA enhanced the compressive strength of CKD-based CPB by improving the reactivity of calcium hydroxide. The addition of the CAA led to elevated the dissolution concentration of cations such as Ca and Si within the system, accelerating both the alkali activation reaction rate and the nucleation rate of the calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C–(A–)S–H) gel. Furthermore, with the increase in CAA content, the pore structure of CKD-based CPB became more complex. Therefore, this study may provide novel insights into the preparation of cost-effective CPB materials with a high CKD content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mine tailings (MT), a hazardous waste product, constitute more than half of the total ore output crushed during the beneficiation process1,2,3. At present, the conventional approach for managing MT involves stacked storage. Nevertheless, the rupture of a mine tailings dam can cause catastrophic harm to both humans and the environment4,5,6. Therefore, cemented paste backfill (CPB), composed primarily of tailings, cementitious materials, and water, is a crucial method for safe tailings management7,8,9,10. Most CPB formulations utilize cement as the primary cementitious material. However, the high cost of cement-based CPB significantly restricts its widespread application. Moreover, cement production releases substantial greenhouse gases and dust, leading to numerous environmental problems11,12. Employing cement kiln dust (CKD) and slag to produce alkali-activated binder materials proves to be an efficient alternative to cement, markedly decreasing filling costs13,14. Researchers7,15,16 have validated the potential use of CKD and slag in CPB. However, there are few studies on CPB with high dosages of CKD.

Proper utilization of alkaline activators can significantly refine pores, enhance microstructure compactness, and improve mechanical strength in CPB preparation. Therefore, alkaline activators have been meticulously selected according to their type and dosage. Alkaline activators involve strong and weakly alkaline activators, with commonly utilized strong alkaline activators including sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium silicate (Na2SiO3)17,18,19. Nonetheless, strongly alkaline solutions elevate the risk of groundwater pollution and entail higher costs20. Given the high fluidity demand of CPB (approximately 2.5–7% water/binder ratio)21, the relative Na+ concentration decreases, resulting in diminished activity of NaOH and Na2SiO32. Consequently, researchers have extensively investigated the preparation of binder materials using weakly alkaline activators like quicklime and sulfate22,23,24. Following the hydration of quicklime, calcium hydroxide improved the bonding capacity of calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C–(A–)S–H) gel, resulting in increased compressive strength in CKD/slag pastes14,25,26,27. Furthermore, calcium sulfate facilitates the formation of calcium hydroxide, elevates system alkalinity, and enhances early specimen strength15,28. However, excessive sulfate in the system can lead to significant precipitation, causing CPB expansion and micro-cracks29.

Binder materials with composite alkaline activator (CAA) demonstrates superior mechanical properties compared to those with a single activator30,31,32. The compressive strength of cement-treated soil enhanced by 40% with 0.4–1% CAA (sulfate and alkali aluminate) content32. Adding a CAA (quicklime and sodium silicate) to slag-based CPB enhanced the alkaline environment, thereby accelerating the slag’s reaction rate and increasing early strength24. Sun et al.3 found that CPB prepared with a CAA comprising calcium carbide slag and carbonate, exhibited a denser microstructure compared to that prepared with a single alkaline activator. However, research on the alkali activation reaction and strength enhancement mechanism of CKD-based CPB activated by CAA composed of quicklime and sulfate remains limited.

Pore volume and distribution are crucial factors influencing the characteristics of CPB33. Porosity refers to the space initially filled with water minus the volume occupied by newly generated reaction products. Lower porosity corresponds to a higher degree of hydration of binder materials in CPB. The C–(A–)S–H gel contributes to microstructure densification and porosity reduction following chemical reactions, serving as a barrier that enhances the corrosion resistance and carbonation capability of CPB34. A strong relationship exists between the pore structure of CPB and the chemical reactions of binder materials35,36. However, there are few researches on the mechanical strength of CKD-based CPB. Further investigation is required to explore the interaction mechanism between compressive strength and pore structure in CKD-based CPB.

Therefore, for the secondary utilization of CKD, most studies employ CKD as the activator to prepare cementitious material, typically in small dosages. Research on CPB primarily focuses on the impact of incorporating strong alkaline activators on its performance. Few studies have investigated the preparation of CPB using a composite weak alkaline activator, high dosages of CKD, slag, and MT as raw materials, and analyzed the hydration mechanism of CPB. This study investigated the effects of a novel CAA, composed of quicklime (CaO) and sulfate (DH-7), on the mechanical properties of CKD-based CPB and evaluated the reaction mechanism influenced by the CAA. The unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of the CKD-based CPB was analyzed after curing for 1, 7, 28, and 60 days. The reaction mechanism was investigated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP), cation exchange capacity (CEC), and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). Changes in reaction products, bonded water, pore structure, morphology of reaction products, and cation dissolution capabilities were investigated under different contents of CAA. This study aimed to propose a novel method for preparing CPB with a high CKD proportion and improving its compressive strength utilizing a CAA.

Materials and methods

Materials

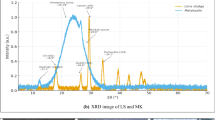

CKD and slag were taken from a factory in Fuxin, Liaoning Province. The total tailings were collected from Sandaogou iron mine in Yedian, Jilin Province37. A Mastersizer 2000 (Malvern, England) particle size analyzer was employed to determine the particle size distribution, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Furthermore, the angular shape and significant size variations of MT particle morphology are depicted in Fig. 2a. When individual particles are magnified, the surface appears extremely rough (see Fig. 2b). The CAA comprises quicklime and sulfate, with the quicklime (CaO) sourced from a local factory. DH-7, developed by this research group as a sulfate activator, is a light gray powder. Its primary constituents include calcium sulfate, sodium carbonate, and other components. It does not require dilution with water, and the addition of DH-7 does not affect the fluidity of CKD-based binders. The microscopic morphology of DH-7 particles is shown in Fig. 3. Table 1 presents the types and proportions of major oxides in the raw materials, tested through X-ray fluorescence (XRF) (XRF-1800, Japan).

Preparation of the specimens

According to the previous findings of the research group, a 6:4 ratio of CKD to slag produced the optimal UCS for the binder paste. In this study, six groups of specimens were fabricated following the procedure illustrated in Fig. 4. The sand-to-binder ratio was 6.0, and the concentration was 74%. The addition of 0.5% polycarboxylic acid superplasticizer ensures that the slump of CPB meets the working performance requirements38,39. Notably, the quicklime (CaO) content was 10%, and the sulfate activator (DH-7) contents were 0%, 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.3%, and 0.5%, denoted as M-10-0, M-10-0.05, M-10-0.1, M-10-0.2, M-10-0.3, and M-10-0.5, respectively. Table 2 shows the mixture proportions for each specimen. CKD, slag, quicklime, and DH-7 were mixed and stirred for 3 min to prepare the CKD-based binder material. Subsequently, the binder material was combined with tailings and stirred for 5 min, followed by the addition of water and an additional 10 min of stirring. The fresh CPB was poured into Φ50 × 100 mm molds, wrapped in plastic wrap, and then stored in a curing box (20 °C ± 2 °C, RH 95%). After curing for 24 h, the specimens were demolded and continued curing for 1, 7, 28, and 60 days.

Characterization methods

Mechanical properties

The UCS of the cylinder specimens was assessed after curing periods for 1, 7, 28, and 60 days40. As shown in Fig. 4, the loading rate of the universal testing machine (WDW-300E, China) was maintained at 1 mm/min. Three replicate specimens were utilized to determine the final UCS value.

Microstructure test

For TGA, MIP, SEM-EDS, CEC, and ICP-OES tests, the specimens were fractured, immersed in anhydrous ethanol to inhibit alkali excitation reactions, and pulverized after curing for 28 days. To avoid moisture absorption and carbonization after grinding, each powder specimen was sealed in airtight packaging.

-

(1)

For qualitative and quantitative analysis of reaction products, the TGA method was employed in a nitrogen environment ranging from 30 to 1000 °C. The heating rate of testing instrument (Mettler TGA/DSC 3 +, Switzerland) was set to 10 °C/min.

-

(2)

SEM (ZEISS EVO 18, Germany) and EDS (OXFORD X-Max20, England) were used to observe the microstructure of CKD-based CPB specimens and analyze the elemental changes in the reaction products. The experimental setup included a voltage acceleration of 20 kV and a working distance of 27 mm. The morphological characteristics of the reaction products were observed in the unpolished samples under ET mode (× 2500 magnification), followed by random selection of two points for EDS testing. The elemental composition changes of the reaction products were analyzed after averaging the test results. The degree of reaction was identified using the polished sample in BSE mode (× 700 magnification).

-

(3)

The variation in pore size of the reaction products was determined using MIP (AutoPore V 9600, USA), with a testing range of 5 nm to 340 μm. Based on the MIP data, the fractal dimension (Ds) was used to analyze the roughness and complexity of the pore structure morphology.

-

(4)

CEC (instrument model: TU-1900, China) was assessed using the hexamminecobalt trichloride solution-spectrophotometric method, considering the specimens’ alkaline nature and significant calcium ion saturation. Following the CEC test, the cationic dissolution of CKD-based CPB was analyzed using ICP-OES (NexION 1000G, USA).

Results and discussion

Mechanical properties

The UCS of CKD-based CPB with different DH-7 contents is shown in Fig. 5. The UCS of CKD-based CPB without DH-7 (M-10-0) was the lowest among all specimens tested. With increasing DH-7 content, the UCS of CKD-based CPB showed a significant increase. With a CaO content of 10%, the UCS of specimens with 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.3%, and 0.5% DH-7 content were 14%, 27%, 43%, 46%, and 32% higher, respectively, compared to those without DH-7. When DH-7 content exceeded 0.3%, the strength enhancement effect diminished, suggesting that the optimal DH-7 content for peak UCS improvement was 0.3%. Compared to the M-10–0 specimen, the UCS of the M-10–0.3 specimen increased by 65%, 46%, and 33% at 7, 28, and 60 days, respectively. The strength enhancement effect was more pronounced in the early stages32. Contrary to previous research41,42, the UCS of CKD-based CPB did not decline after 60 days.

TG-DTG analysis

The type and quantity of reaction products are closely related to the mechanical properties of CKD-based CPB43. Consequently, a combined analysis of TG and DTG was conducted. The TG-DTG curves of the CKD-based CPB specimen mixed with CAA are shown in Fig. 6a. Relevant research indicates that peaks between 50 and 250 °C correspond to the thermal decomposition of interlayer crystal water in C–(A–)S–H gel and ettringite (AFt)44,45. Peak was observed between 450 and 500 °C, corresponding to the dihydroxylation of portlandite (CH)46. A significant peak above 600 °C was mainly due to carbonate decomposition47.

Figure 6b presents the weight loss of different reaction products. With the addition of CAA, the mass fraction of C–(A–)S–H gel and AFt in CPB increased first and then decreased, and the total mass fraction of M-10-0.3 was the highest. CH, the main reaction product in CKD-based CPB with the CAA, exhibited dynamic content changes during continuous production and consumption, derived from four primary sources. (a) The hydration of calcium oxide in quicklime. (b) The dissolution of calcium sulfate in DH-7. (c) The consumption of CH by [SiO4]4–and [AlO4]5– produced in subsequent CKD and slag, resulting in the formation of more gels and AFt. (d) The reaction of CH with sodium carbonate in DH-7 to form a calcium-based product. Therefore, the CAA accelerated the reaction process of CKD-based CPB by influencing CH content. Higher CH reactivity enhanced the reactivity of other products, thereby improving the UCS of the specimens. When the CaO content was 10% and the DH-7 content exceeded 0.3%, the excess activator reduced the reaction rate, resulting in a decrease in the amount of C–(A–)S–H gel and AFt, and an increase in the porosity of CKD-based CPB. This is consistent with the results shown in “Mechanical properties” section, where the UCS of M-10-0.5 was reduced compared to that of M-10-0.3 (Fig. 5).

SEM–EDS analysis

Morphology

To observe changes in the microstructure and surface elements of CKD-based CPB, SEM-EDS analyses were performed before and after the addition of CAA. CKD-based CPB specimens were connected with tailing particles to form a spatial skeleton through C–(A–)S–H gel, AFt, CaCO3, and unreacted CKD-slag binder material filling the voids. As shown in Fig. 7a, CH in the M-10-0 specimen was randomly arranged in rhomboid sheets, extruding and splicing with each other, resulting in a relatively loose structure. Excessive CH caused expansion, reducing the specimen’s mechanical properties. The matrix of the M-10-0 specimen was primarily granular, with obvious voids observed. The C–(A–)S–H gel coated on the surface of the MT particles was relatively thin. Fig. 7b–d presents the micromorphology influenced by the CAA. The CAA enhanced the reaction rate and gel nucleation rate of CKD-based CPB, significantly increasing the number of reaction products. Additionally, the quantity of CH in the observation area was significantly reduced, with most of it coated by gel. The matrix material’s integrity was significantly improved. Notably, no acicular AFt was observed in the SEM images, mainly because the small amount produced was wrapped in the solution pores. The atomic proportions at points 1 and 2 in Fig. 7 were analyzed using EDS, as shown in Table 3. Under the influence of the CAA, the relative content of Ca in the product increased, indicating that the CAA promoted the alkali activation reaction of the system, generating more C–(A–)S–H gel. Additionally, the CAA promoted the partial substitution of [SiO4]4− for [AlO4]5− in the aluminosilicate framework. Consequently, the Si/Al ratio in the EDS analysis increased.

Reaction degree

Figure 8 shows representative BSE images of the reaction products before and after CAA addition. After adding CAA, the number of unreacted raw material particles decreased, the alkali activation reaction rate increased, and the thickness of the hydration products layer increased. With the increase in CAA content, the hydration products continued to increase. The reaction products between adjacent particles gradually merged, and the matrix structure became denser48. However, when CAA was excessive (Fig. 8d), the reaction degree was reduced. The structure of the specimen was relatively loose, with many pores between the unreacted raw material particles.

In summary, Fig. 9 presents the strength enhancement process of CKD-based CPB. The dissolution of the CAA (CaO and DH-7) provided a suitable alkaline environment, increasing the system’s pH value (see Eqs. 1–2). The elevated OH− concentration facilitated the breaking of Si–O and Al-O bonds in binders, releasing active [SiO4]4−and [AlO4]5−. Subsequently, C–(A–)S–H gel was formed by combining these active tetrahedrons with free Ca2+ (see Eq. 3). Additionally, AFt was formed by the reaction between SO42−, an active ingredient in DH-7, and CH (see Eq. 4). CaCO3 primarily resulted from the reaction between partially dissolved Ca2+ from CKD and carbonates in DH-7 (see Eq. 5). However, an excessive amount of DH-7 in the CAA led to rapid early-stage reaction products adsorbing on CKD and slag particle surfaces, hindering further alkali activation reaction and reducing the quantity of reaction products and mechanical properties.

Pore structure characteristics

Figure 10 presents the MIP test results of the CKD-based CPB. As shown in Fig. 10a, the main pore sizes of CKD-based CPB ranged from 19.961 to 183.243 nm, 1318.457 to 5439.702 nm, and 5466.090 to 25,951.92 nm, respectively. When the CaO content was 10%, increasing DH-7 content resulted in an increased number of pores ranged from 19.961 to 183.243 nm and 1318.457 to 5439.702 nm, while the number of pores significantly decreased ranged from 5466.090 to 25,951.92 nm, with all three peak pore sizes shifted left. Additionally, the peak pore size of the M-10–0 specimen was 10,231.316 nm, whereas the peak pore size of the M-10-0.3 specimen significantly reduced to 3788.134 nm. Therefore, the peak pore size of CKD-based CPB significantly reduced with the addition of DH-7. As shown in Fig. 10b, the cumulative volume of mercury and the logarithm of the pore size exhibited an approximate linear trend, indicating that the CKD-based CPB contained pores within the tested size range. When the CaO content was 10%, the cumulative volumes of mercury in the specimens with 0%, 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.3%, and 0.5% DH-7 content were 0.219, 0.170, 0.172, 0.156, 0.153, and 0.174 mL/g, respectively. Simultaneously, the cumulative injected mercury volume of CKD-based CPB significantly decreased with the addition of DH-7.

Table 4 shows the pore structure parameters obtained from the MIP test. It can be seen from Table 4 that the CAA changed the pore distribution. The porosity gradually decreased while the UCS gradually increased, which is consistent with the research results of Min et al.49. When the CaO content was 10%, both the mean pore size and the most prevalent pore size decreased with increasing DH-7 content, indicating that the addition of DH-7 promoted the formation of reaction products and reduced the internal pore diameter of CKD-based CPB. The pore size in the M-10-0.3 specimen was the smallest, indicating the largest number of reaction products and the best mechanical properties50. Additionally, Fig. 11 shows the pore size percentages based on Table 451. The most significant influence of CAA was on the large pores. A large number of reaction products filled the inner surfaces of the pores, causing macropores to split into smaller pores, and the gel and capillary pores increased significantly. However, when the DH-7 content was 0.5%, the alkali activation reaction rate slowed, and the amount of reaction product decreased. Consequently, the proportion of gel and capillary pores decreased, and the overall porosity increased.

Pore structure complexity analysis

The roughness and complexity of pore structure morphology can be analyzed using fractal theory52. According to the model proposed by Zhang et al.53, the fractal dimension (Ds) is primarily calculated using Eqs. (6–7).

where, i denotes the i-th injection of mercury; Pi is the pressure at the i-th injection of mercury (Pa); Vi is the mercury injection volume at the i-th injection (m3).

where, Wn is the cumulative work of mercury injection during the first n injections (m3); rn is the pore radius of the n-th mercury intrusion (m); C is the model parameter.

Figure 12 shows the double logarithmic diagram representing the fractal characteristics of CKD-based CPB. The accuracy of Ds was evaluated using the determination coefficient (R2). Generally, when the Ds value is 2, pore structure is smooth and planar. When the Ds value approaches 3, the pore structure and surface topography become more complex and rough43. Therefore, the pore structure of CKD-based CPB exhibited clear fractal characteristics (2 < Ds < 3). Additionally, with the increase of DH-7 content, the Ds value initially increased and then decreased. Combined with the pore structure characteristics in “Pore structure characteristics” section, the addition of CAA promoted the alkaline activation reaction of CKD-based CPB, resulting in more reaction products filling large pores and creating additional small pores. Therefore, the pore structure of CKD-based CPB specimens became more complex and irregular, manifested by an increase in the Ds value.

Analysis of cation dissolution and exchange capacity

The presence of cations in binder materials, such as Ca2⁺, Si4⁺, and Al3⁺, is crucial in the reaction process. These cations accelerate the alkali activation reaction, leading to an increased production rate and quantity of reaction products54,55. Furthermore, cations significantly affect the porosity of the specimen. The exchange of cations with anions can improve the pore distribution and properties of the binder material. Figure 13 presents the change in cation solubility of the CKD-based CPB specimens. As shown in Figure 13a, the CEC values of CKD-based CPB specimens significantly decreased with the addition of CAA, indicating a reduction in the amounts of exchangeable cations. This was mainly because the cations in CAA cannot be exchanged by ammonium salts and remain adsorbed on the specimen’s surface. Figure 13b shows the concentrations of major cations involved in the reaction tested by ICP-OES. The ion dissolution in the M-10–0.3 specimen was the highest, whereas in the M-10–0 specimen, it was the lowest. Following the addition of the CAA, the dissolved concentration of Al gradually decreased. This indicated that aluminosilicates recombined, with more Si–O bonds replacing Al-O bonds, resulting in decreased Al content in the solution. This was consistent with the EDS analysis results (Table 4). When the CaO content was 10% and the DH-7 contents were 0%, 0.2%,0.3%, and 0.5%, the Ca concentrations were 3954, 5044, 6060, and 4580 mg/L, respectively. The Ca concentration increased initially and then decreased, indicating that the CAA primarily promoted Ca2+ participation in the reaction process and gel formation.

Conclusions

In this work, CPB was prepared using quicklime (CaO) and sulfate (DH-7) as a CAA, with CKD and slag as the primary raw materials, and MT as aggregate. The effect of CAA on mechanical properties of CKD-based CPB was studied. TGA, SEM–EDS, MIP, CEC, and ICP-OES were utilized to investigate the reaction products, pore structure, and cation dissolution capacity of CKD-based CPB. The results can be summarized as follows:

-

(1)

The CAA promoted the alkali activation reaction and improved the nucleation efficiency of the gel. When the content of CaO was 10% and DH-7 was 0.3%, the UCS of CPB prepared from iron tailings reached 4.16 MPa after 28 days. Compared to using CaO alone, the UCS increased by 46%, with no loss of strength after long-term curing and a more pronounced effect on early strength.

-

(2)

Under the influence of CAA, the primary chemical products of CKD-based CPB were CH, AFt, C-(A-)S–H gel, and CaCO3. SEM–EDS and ICP-OES analyses indicated that the CAA promoted the precipitation of strong cations in the system solution. Furthermore, the binding of Si to the gel in the pore solution increased, and the Ca/Si and Si/Al ratios in the gel were elevated. SO42- replaced other anions in the aqueous phase, enhancing the bonding between the gel and the tailings particles.

-

(3)

As the main reaction product, CH primarily originated from four sources in its continuous production and consumption. (a) Hydration of CaO from quicklime. (b) Dissolution of calcium sulfate from DH-7. (c) Consumption of CH by the activity of [SiO4]4- and [AlO4]5- produced in CKD and slag, leading to the formation of more gels and AFt. (d) Reaction of CH with sodium carbonate from DH-7 to form calcium-based reaction products. Therefore, the CAA accelerated the reaction process of CKD-based CPB by enhancing the reactivity of CH.

-

(4)

The CAA significantly improved the pore structure of CKD-based CPB. A large number of reaction products filled the inner surfaces of the pores, causing macropores to split into gel and capillary pores, which significantly decreased the overall porosity. Additionally, the fractal dimension (Ds) of the surface pores increased, making the pore structure morphology more complex.

The use of a CAA consisting of quicklime (CaO) and sulfate activator (DH-7) combined with CKD-slag binder material is a feasible method to stabilize tailings. Although the strength enhancement mechanism of CKD-based CPB under the influence of CAA has been studied using various microscopic analysis methods, there are still gaps that require further investigation, particularly regarding the behavior of colloids. For example, the interaction of electrostatic forces in colloids under the influence of CAA requires further testing and analysis.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request. To request data from this study, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Nasharuddin, R. et al. Understanding the microstructural evolution of hypersaline cemented paste backfill with low-field NMR relaxation. Cem. Concr. Res. 147, 106516 (2021).

Roshani, A. & Fall, M. Rheological properties of cemented paste backfill with nano-silica: Link to curing temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 114, 103785 (2020).

Sun, X., Liu, J., Qiu, J., Wu, P. & Zhao, Y. Alkali activation of blast furnace slag using a carbonate-calcium carbide residue alkaline mixture to prepare cemented paste backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 320, 126234 (2022).

Fall, M. & Pokharel, M. Coupled effects of sulphate and temperature on the strength development of cemented tailings backfills: Portland cement-paste backfill. Cem. Concr. Compos. 32(10), 819–828 (2010).

Silva Rotta, L. H. et al. The 2019 Brumadinho tailings dam collapse: Possible cause and impacts of the worst human and environmental disaster in Brazil. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 90, 102119 (2020).

Barcelos, D. A. et al. Gold mining tailing: Environmental availability of metals and human health risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 397, 122721 (2020).

Zhang, S., Yang, L., Ren, F., Qiu, J. & Ding, H. Rheological and mechanical properties of cemented foam backfill: Effect of mineral admixture type and dosage. Cem. Concr. Compos. 112, 103689 (2020).

Xue, G. & Yilmaz, E. Strength, acoustic, and fractal behavior of fiber reinforced cemented tailings backfill subjected to triaxial compression loads. Constr. Build. Mater. 338, 127667 (2022).

Guo, Z. et al. A contribution to understanding the rheological measurement, yielding mechanism and structural evolution of fresh cemented paste backfill. Cem. Concr. Compos. 143, 105221 (2023).

Vigneaux, P., Shao, Y. & Frigaard, I. A. Confined yield stress lubrication flows for cement paste backfill in underground stopes. Cem. Concr. Res. 164, 107038 (2023).

Adesina, A. & Das, S. Drying shrinkage and permeability properties of fibre reinforced alkali-activated composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 251, 119076 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Utilization of solid wastes to sequestrate carbon dioxide in cement-based materials and methods to improve carbonation degree: A review. J. CO Util. 72, 102502 (2023).

Kaliyavaradhan, S. K., Ling, T. C. & Mo, K. H. Valorization of waste powders from cement-concrete life cycle: A pathway to circular future. J. Clean. Prod. 268, 122358 (2020).

Hu, M. H., Dong, T. W., Cui, Z. L. & Li, Z. Mechanical behavior and microstructure evaluation of quicklime-activated cement kiln dust-slag binder pastes. Materials 17(6), 1253 (2024).

Tariq, A. & Yanful, E. K. A review of binders used in cemented paste tailings for underground and surface disposal practices. J. Environ. Manage. 131, 138–149 (2013).

Peyronnard, O. & Benzaazoua, M. Alternative by-product based binders for cemented mine backfill: Recipes optimisation using Taguchi method. Miner. Eng. 29, 28–38 (2012).

Barrie, E. et al. Potential of inorganic polymers (geopolymers) made of halloysite and volcanic glass for the immobilisation of tailings from gold extraction in Ecuador. Appl. Clay Sci. 109–110, 95–106 (2015).

Ahmari, S. & Zhang, L. Utilization of cement kiln dust (CKD) to enhance mine tailings-based geopolymer bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 40, 1002–1011 (2013).

Kiventerä, J. et al. Alkali activation as new option for gold mine tailings inertization. J. Clean. Prod. 187, 76–84 (2018).

Alventosa, K. M. L., Wild, B. & White, C. E. The effects of calcium hydroxide and activator chemistry on alkali-activated metakaolin pastes exposed to high temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 154, 106742 (2022).

Ouffa, N., Trauchessec, R., Benzaazoua, M., Lecomte, A. & Belem, T. A methodological approach applied to elaborate alkali-activated binders for mine paste backfills. Cem. Concr. Compos. 127, 104381 (2022).

Shi, P., Falliano, D., Yang, Z., Marano, G. C. & Briseghella, B. Investigation on the anti-carbonation properties of alkali-activated slag concrete: Effect of activator types and dosages. J. Build. Eng. 91, 109552 (2024).

Rojas-Martínez, A. E., González-López, J. R., Guerra-Cossío, M. A. & Hernández-Carrillo, G. Sulphate-based activation of a binary and ternary hybrid cement with portland cement and different pozzolans. Constr. Build. Mater. 421, 135683 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Preparation and strength mechanism of slag-based mine backfill for low concentration ultra-fine tailings. Constr. Build. Mater. 384, 131457 (2023).

Dai, X., Aydın, S., Yardımcı, M. Y., Lesage, K. & Schutter, G. D. Effect of Ca(OH)2 addition on the engineering properties of sodium sulfate activated slag. Materials. 14, 4266 (2021).

Zhai, Q. & Kurumisawa, K. Mechanisms of inorganic salts on Ca(OH)2-activated ground granulated blast-furnace slag curing under different temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 338, 127637 (2022).

Cai, G. H., Zhou, Y. F., Li, J. S., Han, L. J. & Poon, C. S. Deep insight into mechanical behavior and microstructure mechanism of quicklime-activated ground granulated blast-furnace slag pastes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 134, 104767 (2022).

Osmanovic, Z., Haračić, N. & Zelić, J. Properties of blastfurnace cements (CEM III/A, B, C) based on Portland cement clinker, blastfurnace slag and cement kiln dusts. Cem. Concr. Compos. 91, 189–197 (2018).

Li, W. & Fall, M. Sulphate effect on the early age strength and self-desiccation of cemented paste backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 106, 296–304 (2016).

Nematollahi, B. & Sanjayan, J. Effect of different superplasticizers and activator combinations on workability and strength of fly ash based geopolymer. Mater. Des. 57, 667–672 (2014).

Chang, N. et al. Improved macro-microscopic characteristic of gypsum-slag based cementitious materials by incorporating red mud/carbide slag binary alkaline waste-derived activator. Constr. Build. Mater. 428, 136425 (2024).

Xu, F., Wei, H., Qian, W. & Cai, Y. Composite alkaline activator on cemented soil: Multiple tests and mechanism analyses. Constr. Build. Mater. 188, 433–443 (2018).

Tian, X. C. & Fall, M. M. D. Non-isothermal evolution of mechanical properties, pore structure and self-desiccation of cemented paste backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 297, 123657 (2021).

Liu, S. & Fall, M. Fresh and hardened properties of cemented paste backfill: Links to mixing time. Constr. Build. Mater. 324, 126688 (2022).

Ouellet, S., Bussière, B., Aubertin, M. & Benzaazoua, M. Microstructural evolution of cemented paste backfill: Mercury intrusion porosimetry test results. Cem. Concr. Res. 37(12), 1654–1665 (2007).

Luo, R., Cai, Y., Wang, C. & Huang, X. Study of chloride binding and diffusion in GGBS concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 33(1), 1–7 (2003).

GB/T 39489–2020, Technical specification for the total tailings paste backfill, (2020).

Chen, Q., Zhang, Q., Fourie, A., Chen, X. & Qi, C. Experimental investigation on the strength characteristics of cement paste backfill in a similar stope model and its mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 154, 34–43 (2017).

GB/ 50080–2002, Standard for test method of performance on ordinary fresh concrete, (2002).

GB/T 50081–2019, Standard for test methods of concrete physical and mechanical properties, (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Long-term performance of silane coupling agent/metakaolin based geopolymer. J. Build. Eng. 36, 102091 (2021).

Xu, H. & Van Deventer, J. S. J. The geopolymerisation of alumino-silicate minerals. Int. J. Miner. Process. 59(3), 247–266 (2000).

Liu, L. et al. Experimental investigation on the relationship between pore characteristics and unconfined compressive strength of cemented paste backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 179, 254–264 (2018).

Qin, L., Gao, X. & Li, Q. Upcycling carbon dioxide to improve mechanical strength of Portland cement. J. Clean. Prod. 196, 726–738 (2018).

Fernández, Á., García Calvo, J. L. & Alonso, M. C. Ordinary Portland cement composition for the optimization of the synergies of supplementary cementitious materials of ternary binders in hydration processes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 89, 238–250 (2018).

Shah, V. & Scott, A. Hydration and microstructural characteristics of MgO in the presence of metakaolin and silica fume. Cem. Concr. Compos. 121, 104068 (2021).

Wang, L., Yeung, T. L. K., Lau, A. Y. T., Tsang, D. C. W. & Poon, C. S. Recycling contaminated sediment into eco-friendly paving blocks by a combination of binary cement and carbon dioxide curing. J. Clean. Prod. 164, 1279–1288 (2017).

Peng, Y. et al. BSE-IA reveals retardation mechanisms of polymer powders on cement hydration. J. Build. Eng. 103, 3373–3389 (2020).

Min, C. et al. Effect of mixing time on the properties of phosphogypsum-based cemented backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 210, 564–573 (2019).

Dayioglu, M., Cetin, B. & Nam, S. Stabilization of expansive Belle Fourche shale clay with different chemical additives. Appl. Clay Sci. 146, 56–69 (2017).

Lan, X. L., Zeng, X. H., Zhu, H. S., Long, G. C. & Xie, Y. J. Experimental investigation on fractal characteristics of pores in air-entrained concrete at low atmospheric pressure. Cem. Concr. Compos. 130, 104509 (2022).

Ji, X., Chan, S. & Feng, N. Fractal model for simulating the space-filling process of cement hydrates and fractal dimensions of pore structure of cement-based materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 27(11), 1691–1699 (1997).

Zhang, B. & Li, S. Determination of the surface fractal dimension for porous media by mercury porosimetry. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 34(4), 1383–1386 (1995).

Yang, P. et al. Study on the curing mechanism of cemented backfill materials prepared from sodium sulfate modified coal gasification slag. J. Build. Eng. 62, 105318 (2022).

Etcheverry, J. M., Villagran-Zaccardi, Y. A., Van den Heede, P., Hallet, V. & De Belie, N. Effect of sodium sulfate activation on the early age behaviour and microstructure development of hybrid cementitious systems containing Portland cement, and blast furnace slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 141, 105101 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H.H. and T.W.D. conceptualized the study. M.H.H. curated the data and developed the methodology. M.H.H. wrote the original draft. T.W.D. supervised the project, performed formal analysis, and managed the project administration. T.W.D. and Z.L.C. worked on the visualization. Z.L.C. handled the investigation and resources. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, M., Dong, T. & Cui, Z. Effects of composite alkaline activator on mechanical properties and hydration mechanism of cemented paste backfill with cement kiln dust. Sci Rep 14, 28979 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80398-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80398-y