Abstract

Ultrasonic detection has emerged as a rapid method for acquiring rock mass sound velocity and converting it into an elastic modulus parameter, a pivotal technique for investigating the in-situ mechanical properties of rock masses. Despite its significance, accurately deducing rock mass strength from elastic modulus remains a formidable challenge and a pressing issue in the realm of protorock parameter research. This study introduces an innovative artificial intelligence-driven methodology for transforming elastic modulus and strength parameters specific to coal measures through rigorous data analysis and experimental validation. By integrating two illustrative engineering cases, we explore the complexities of water inrush and floor heave issues encountered in tunnels traversing fault zones. The novel strength parameter calculation approach is benchmarked against previous studies, highlighting its superior advantages in terms of effectiveness and applicability. In essence, this research offers a comprehensive framework and practical workflow for translating in-situ acoustic parameter-derived elastic modulus into rock mass strength, serving as a valuable resource for future endeavors in mine water control research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The scientific and precise estimation of grouted rock mass mechanical parameters is of paramount importance in investigating scientific quandaries such as the extent of damage to the grouting working face floor and the peril of aquifer water inrush1,2. Presently, the estimation of these parameters is commonly achieved through rock mechanics experiments and the consultation of pertinent literature. However, these methodologies are hampered by lengthy practical cycles and constraints arising from construction conditions, which in turn restrict the efficiency and accuracy of research concerning grouting reconstruction on working faces3. Simultaneously, obtaining in-situ rock mass mechanical parameters, whether for post-grouting transformation or untreated rock masses, are quite difficult. Recent seminal studies have revealed that ultrasonic detection offers expeditious acquisition of original rock velocities, subsequently translatable into rock elastic modulus parameters, constituting one of the efficacious methodologies for probing in-situ rock mass mechanical traits. However, the conundrum persists regarding the precise derivation of original rock compressive strength from elastic modulus, posing a formidable obstacle in original rock parameter research4.

Acquiring the dynamic characteristics of grouted rock masses and conventional rock masses poses considerable difficulty. Qian5 delineated equations correlating dynamic Poisson’s ratio, dynamic elastic modulus, dynamic bulk modulus, and elastic wave velocity of rock masses. Discerned the exponential pattern between rock strength and strain rate through a multitude of static and dynamic experiments on various rock types, elucidating the dynamic-static elastic modulus relationship6. Ultrasonic testing techniques was employed to gauge the fluctuation of acoustic wave velocity within differently fractured rock masses, unraveling the nexus between rock mass fracture damage and grouting reinforcement7. Concurrently, with the incessant evolution of experimental methodologies and technologies, researchers delving into grouted rock masses have also embraced the utilization of digital image correlation (DIC), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and other methodologies to scrutinize microstructural attributes8. Kao9 reported the research of mechanical attributes of fractured mudstone reinforced by grouts utilizing a Hopkinson pressure bar apparatus.

To address an array of quandaries such as the coal floor’s depth of damage and the aquifer water inrush mechanism, it is imperative to initiate from the in-situ rock mechanical properties of the coal floor10. Ultrasonic detection swiftly procures the original rock velocity, subsequently translatable into original rock elastic modulus parameters on-site11. By amalgamating laboratory rock mechanics experimental data, a methodology tailored for investigating the original rock elastic modulus and strength of coal-bearing strata post-grouting transformation is proposed, employing artificial intelligence learning parameter conversion methodologies. In the assessment of water inrush hazards on mining face floors and the in-situ engineering of fractured rock mass tunnels, innovative methodologies are deployed, and their precision is assessed2. Despite the relative ease of ultrasonic testing, when confronted with the intricate and diverse geological formations in coal mines, the analysis of pertinent rock mass strength issues necessitates cross-verification through other geophysical methods. This approach enhances the credibility of the ultrasonic detection outcomes, thereby facilitating a more accurate interpretation of the on-site conditions3,5.

This paper studies the elastic modulus and compressive strength parameters of rock mass obtained through field coring and grouting experiments on coal seam floor, collects relevant data from existing literature, establishes an artificial intelligence learning method suitable for studying the elastic modulus and strength parameters of coal-bearing strata, and calculates the corresponding compressive strength using general supervised learning algorithms based on the elastic modulus of rock mass after acoustic wave conversion in the borehole measured on site. By classifying and fitting multiple sets of elastic modulus and compressive strength parameters based on lithology, a parameter equation suitable for coal-bearing strata and convenient for use was formulated, such as providing a relationship equation between elastic modulus and compressive strength for coal-bearing strata suitable for a certain mining area. Through analysis of two engineering case studies, the strength parameters computed from the fitted equations are utilized to address water inrush issues in coal floor mining and floor heave problems in faulted roadway tunnels, demonstrating the advantages of the novel strength parameter calculation method compared to existing research12. Overall, this study proposes a method and application process for converting elastic modulus into rock strength based on on-site acoustic wave parameters.

Materials and methods

In recent years, the eastern section of the I district in Zhaogu No. 2 Mine has experienced three significant water inrush incidents, all of which have substantially impacted workplace safety. These incidents were concentrated between the V east crosscut and the return airway of the 1107 working face in the uphill area of the I district. The 11,030 working face of this mine represents a high-extraction working face, with certain areas of the L2 limestone and O2 limestone floor posing water inrush risks during the mining process. Therefore, integrating geological factors and engineering requirements, rock mass samples were collected from the eastern section of the I district and the return airway of the 11,030 working face. Sample preparation is an essential part of laboratory test in mining engineering. The sample was obtained from the Taiyuan Formation of the Carboniferous Permian, Zhaogu 2 mine, Henan Province, Central China (Fig. 1a).

Direct determination of this parameter in the laboratory is carried out according to standards of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and the International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM)13 The rock core samples, initially with a diameter of Φ = 55 mm, are processed in the laboratory into cylindrical specimens measuring Φ50 mm × 100 mm. The formed rock samples underwent a grinding process to ensure that the parallelism deviation was no greater than 0.5 mm and the dimensional deviation at both ends was less than 0.2 mm. This process ensured that the end faces of the specimens were perpendicular to the specimen axis. Some of the samples are shown in Fig. 1b.

Experiments and methods

Compression test

The MTS816 rock mechanics test system, along with its complementary test setup, is utilized for conducting mechanical property assessments of rock samples. This comprehensive testing apparatus encompasses a load frame, pump unit, controller unit, and pressure sensor mounted unit. It enables the acquisition of data pertaining to axial (ring) stress and strain peak strength, elastic modulus, as well as load, deformation, and displacement throughout the experimental procedure.

Measurement of rock wave velocity and conversion to elastic modulus

The internal wave velocity within rocks serves as a indicator of the physical and mechanical properties of rock masses. The dynamic detection method relies on the established relationship between the internal wave velocity of rock masses and their elastic moduli14. Equation (1) facilitates the calculation of the dynamic young’s modulus of rock masses. The reinforcement degree λ (Eq. 3) of the dynamic young’s modulus of rock masses after grouting is proposed based on the elastic modulus of rock masses and their rates of change, offering a quantitative depiction of the alteration in rock mass elastic modulus pre- and post-grouting2.

In this equation: ρ represents the density of the rock mass, in g/cm3, Ed and \(E_{d}^{\prime }\) respectively denote the dynamic elastic modulus of the rock mass before and after grouting, in GPa; ΔE signifies the change in dynamic elastic modulus of the rock mass before and after grouting, in GPa; μd denotes the Poisson’s ratio of the rock mass; and Vp represents the longitudinal wave velocity within the rock mass.

The set up for the determination of the longitudinal wave velocity inside the rock is shown in Fig. 2. UTA2001A ultrasonic inspection monitor is used for ultrasonic test of the rock sample. When the measurement is made in the opposite way, the length L of the sample is measured accurately with the vernier caliper first, that is, the distance between the receiving and transmitting transducers. After the acoustic wave emitted by the transmitting transducer passes through the rock sample, it is captured by the receiving transducer, and the acoustic wave waveform is displayed on the instrument screen. The instrument automatically determines and calculates the propagation time T of the p-wave in the rock sample based on the waveform. Then, the propagation velocity Vp of P-wave in the sample is calculated by formula (4).

Prediction of rock uniaxial strength

Artificial intelligence learning prediction leverages the data foundation and data mining capabilities to their fullest potential, rendering it a widely adopted approach15,16. Supervised learning encompasses classification and regression tasks, whereas unsupervised learning predominantly serves for frequent item set mining17. Commonly utilized supervised learning algorithms comprise the k-nearest neighbors (K-NN) method, random forest (RF) method, artificial neural network (ANN) method, and linear regression (LR) method.

-

(1)

K-NN method18: The nearest neighbor algorithm is an instance-based learning approach. In its simplest form, it selects the most common class or takes the average among the k nearest neighbors. Initially, the classification samples are partitioned based on the feature vector values of the training sample library. Then, the individual sample with the smallest distance to the sample to be classified is selected as the Kth nearest neighbor according to the distance function. Finally, discrimination is based on the distances of the nearest neighbors. This method does not require the generation of additional data parameters for rule description; the data itself forms the rule, and it does not demand data consistency, meaning it has a lower sensitivity to noise. It exhibits excellent handling capabilities for nonlinear problems and is suitable for multi-classification scenarios.

-

(2)

RF method19: The Random Forest (RF) method initially utilizes the Bootstrap method of repeated resampling to randomly extract samples from the training sample library. The samples after extraction are used for decision tree modeling and combination. Finally, the final learning result is obtained through voting, addressing the issue of the inability of a single Bootstrap to further improve performance. Numerous practical and theoretical studies have demonstrated the high accuracy of this method, along with its good tolerance for noise and outliers, and generally, the fitting results do not suffer from overfitting.

-

(3)

ANN method20: The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) method entails data analysis learning by simulating the complex neuronal structure of the brain. Typically, ANN constructs multiple layers of neurons, with the first and last layers designated as the input and output layers, respectively, while one or more hidden layers are sandwiched in between. Each neural layer comprises numerous processing units interconnected through weight coefficients. During the learning process, information is first received, predictions are then transmitted to the next layer, and this iterative process continues until complex nonlinear data learning is accomplished.

-

(4)

LR method21: The Linear Regression (LR) is a technique that establishes a regression model based on the relationship between two variables, namely the independent variable and the dependent variable, and utilizes the model to evaluate the impact of variables on learning outcomes. In actual data learning processes, the factors influencing variables are relatively complex. A univariate linear regression may not accurately reflect the relationship between the independent and dependent variables, thus necessitating the inclusion of a multivariate multilayer linear regression model. Linear regression typically employs the least squares method to minimize the perpendicular distance between the fitted line and each data point, thereby predicting the model by minimizing the sum of distances.

Results

Calculation result of artificial intelligence algorithm

Based on the aforementioned algorithm principles and characteristics, four artificial intelligence learning prediction methods are initially employed to establish a relationship model between the elastic modulus and compressive strength of rock masses, and the data is subjected to training analysis. Ultimately, based on the performance of the learning outcomes of the two variables using these four methods, the most suitable approach is determined as the model for converting parameters of the grouted rock mass in the coal floor.

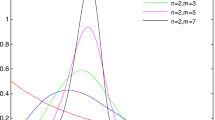

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between the elastic modulus and strength of the coal-bearing strata and grouted mass based on four different learning methods. Due to the complex genesis of coal-bearing strata, their mechanical properties are significantly affected by mining activities, causing some data points to still fall outside the confidence interval after learning is completed. Based on criteria such as maximum tolerance for noise and smoothness of the result curve, the K-NN method is considered the optimal algorithm among the four learning methods.

The utilization of artificial intelligence learning methodologies promises enhanced reliability in forecasting parameters. Once the optimal artificial intelligence learning model for determining the elastic modulus and compressive strength of coal measure strata and grouting bodies is established, rock formations with known elastic modulus or compressive strength can be integrated into the model to derive corresponding parameters22. Notably, extensive studies on coal measure strata in the Jiaozuo mining area provide valuable insights. Thus, collating elastic modulus data from pertinent literature can inform the K-NN algorithm model to predict compressive strength as part of the predictive dataset.

Rock mineral composition, diagenesis, and micro-structure have important effects on the macroscopic mechanical behavior of rocks. It is difficult to study the effects of all the different conditions on the macroscopic mechanical behavior. Our rock specimens were selected from the Jiaozuo mine formation, and the elastic modulus and compressive strength were obtained by uniaxial compression experiments and ultrasonic detection. Also to improve the accuracy of the AI algorithm, we selected data from some literature about the Jiaozuo mining area23,24,25. Calculations draw from diverse sources including scholarly literature, project reports, and experimental findings.

Numerical relationship between elastic modulus and compressive strength

In practical engineering applications, in order to broaden the utilization scope and simplify the study of the relationship between elastic modulus and compressive strength, known single-parameter variables of rock formations are introduced into the learning model. Subsequently, after computing the dependent variables, all data are consolidated, and a numerical equation representing the relationship between the elastic modulus and compressive strength of coal measure strata is derived through data fitting. For instance, an equation tailored to the Jiaozuo mining area, describing the relationship between the elastic modulus and compressive strength of coal measure strata, can be presented.

The experimental data underwent lithology-based segmentation and subsequent fitting, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Throughout the fitting procedure, various function types including ExpDec, Gauss, and Boltzmann were individually tested. Upon comparison, it was observed that both Logistic and Linear function types yielded superior fitting results and correlation coefficients compared to other function types. The correlation coefficients between fitting function forms and different types of rock formations are detailed in Table 1.

Compared with Fig. 4, it can be seen that the overall relationship of samples changed from discrete to relatively neat after classifying statistics according to lithology. Each sample point in the figure is basically evenly distributed around the fitting function curve, indicating that the data sample after lithology classification can become a statistical set, and the corresponding fitting results have good representativeness, pertinency and accuracy. The fitting results showed that the Logistic function R2 after fitting all the data was 0.63, and the minimum R2 value of the model after classification fitting was 0.80, among which the R2 of the three lithologies was 0.91, which belonged to obvious correlation.

After thorough consideration of the artificial intelligence learning prediction method and the results of function model fitting, parametric equations for compressive strength and elastic modulus are derived from a theoretical standpoint. In the practical coal mining operations, rock mass parameters can be determined using the Logistic fitting relationship, thus offering a foundational framework for addressing issues such as water inrush and floor heave on the working face.

Application I: risk analysis of water inrush in floor of working face

Engineering situations

The 11,030 working face of Zhaogu No. 2 Mine represents a high mining height site, situated at a depth of −682 m and positioned at the upper section of the I panel. The precise location of this working face is delineated in Fig. 5. The primary coal seam corresponds to the Shanxi Formation 21 coal seam, boasting an average strike length of 2.13 km and an inclined length of 180 m, with a recoverable reserve estimated at 3.172 million tons. The hardness coefficient of the coal seam ranges from 0.98 to 1.8, while the dip angle varies from 0 to 12 degrees. The seam exhibits a thickness spanning from 4.73 to 6.77 m. Employing the longwall mining technique, extraction progresses in a backward manner along the roof, with each mining operation targeting a full thickness of 6 m. Adjustments to the mining height are made as necessary upon encountering structural complexities.

The L8 limestone layer beneath the coal seam floor resides approximately 28 m away on average, with the maximum water pressure reaching approximately 7.4 MPa. Based on field measurements, the failure depth of the 11,030 high mining face’s floor extends to 34.8 m. Specifically, the threat of water inrush is confined to select zones within the L2 and O2 limestone layers of the floor, particularly during periods of high-intensity mining activities. Consequently, grouting reinforcement is implemented along the working face and coal seam floor to transform the L8 limestone into an impermeable stratum.

Water inrush risk assessment method of grouting face

-

(1)

Failure depth of working face bottom plate and thickness of waterproof layer

Towards the end of the stope, stress concentration ensues at the coal wall during the mining process, signifying the severity of deformation and failure within the floor rock mass at this specific location, where the failure depth reaches its maximum26,27. Zhang28 was the first to propose the distribution pattern of the mining-induced failure zones within the floor rock mass, drawing from both field measurements and theoretical deductions. The interface spanning the “lower three zones” from the coal seam floor to the apex of the aquifer delineates Zone I (floor water conduction failure zone), Zone II (water obstruction zone), and Zone III (confined water lifting zone), with respective heights denoted as h1, h2, and h3, and h3 obtained from the mine geology manual of Zhaogu, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Zone I thickness (h1, derived by fracture mechanics):

$$h_{1} = \frac{{1.57\gamma^{2} h^{2} L}}{{4R_{c}^{2} }}$$(5)Zone II thickness (h2):

$$h_{2} = h - h_{1} - h_{3}$$(6) -

(2)

Evaluation index of water inrush on grouting face

Four commonly employed evaluation indices are utilized to assess water inrush in the bottom plate of the grouting-reinforced working surface29:

-

(1)

Coefficient of water inrush:

$$T = \frac{P}{{h_{2} }}$$(7) -

(2)

Thickness of the safety hose derived from thin plate theory (h2s):

$$\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {h_{2s} = \frac{{\sqrt {\gamma^{2} + 2{\text{A}}\left( {P - \gamma h_{1} } \right)R_{t} - } \gamma }}{{{\text{A}}R_{t} }}} \hfill \\ {{\text{A}} = \frac{{12l_{x}^{2} }}{{l_{{\text{y}}}^{2} \left( {\sqrt {l_{{\text{y}}}^{2} + 3L^{2} } - l_{y} } \right)^{2} }}} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$(8) -

(3)

Theoretical value of safe water pressure for the baseplate (Pla):

$$P_{la} = \frac{{2R_{t} h_{2}^{2} }}{{L^{2} }} + \frac{{\gamma \left( {h_{1} + h_{2} } \right)}}{{10^{6} }}$$(9) -

(4)

Method for evaluating the limit water pressure (Pmax):

$$\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {P_{\max } = B(h - h_{1} )^{2} R_{t} + \gamma h} \hfill \\ {B = 12l_{x}^{2} l_{y}^{ - 2} /(\sqrt {l_{y}^{2} + 3l_{x}^{2} } - l_{y} )^{2} } \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$(10)where P is the floor aquifer water pressure, in MPa; L is the maximum control distance of the working face, in meters; γ is the average bulk density of the bottom water-barrier layer, in MN/m3; H is the mining depth of the coal seam, in meters; Rt and Rc respectively represent the average uniaxial tensile and compressive strength of the bottom waterproof layer, in MPa; lx and ly are the length and width of the working face, in meters.

There are numerous factors influencing the depth of the failure zone h1, with uniaxial compressive strength (Rc) exerting the most significant impact, while the interactions among other factors are not simply linear. Hence, during the actual calculation process, reliance on artificial intelligence learning prediction outcomes, coupled with geological considerations, becomes imperative to discern primary and secondary factors, adjust relevant parameters accordingly, and derive more precise results.

Geophysical prospecting results of working face treatment

To mitigate water inrush from the floor of the working face and ensure the safe extraction of confined water, floor grouting transformation technology is introduced. The grouting reinforcement schemes for the coal seam floor of the 21 coal seam are delineated as follows: for stratified mining working faces, reinforcement extends to the coal seam floor with a descent distance of 60 m; meanwhile, for working faces with substantial mining height, reinforcement extends to the coal seam floor with a descent distance of 85 m, nearing the L2 top interface, effectively transforming the L8 limestone aquifer into a water-retaining layer through grouting reinforcement.

-

(1)

Ultrasonic logging results

The wave velocity (Vp) of the rock mass at various depths of the floor is obtained through the ultrasonic logging method23 of “single-transmitter and dual-transceiver”, with the measurement outcomes illustrated in Fig. 7. Noticeably, the Vp of the rock mass in the face floor exhibits significant variation in the vertical direction. The influence of Vp is intricately intertwined not only with lithology but also with the depth of the same lithology. Notably, the lowest Vp of the floor rock mass before grouting registers at 0.62 km/s. Subsequently, post-grouting, the Vp escalates to a range of 1.73–3.27 km/s, marking a 2.3-fold surge compared to its pre-grouting state. However, the Vp post-mining undergoes fluctuations due to mining activities, fluctuating between 0.8 and 1.95 km/s, with an average decline of 24%. Nonetheless, the overall Vp of the rock mass remains superior to that before grouting. Moreover, the Vp of the rock mass after grouting showcases relative uniformity within similar lithology, exhibiting minimal fluctuations. This observation underscores the efficacy of grouting reinforcement technology in ameliorating the lithologic parameters of the rock mass impacted by mining activities.

Fig. 7 Upon scrutinizing the aforementioned measured outcomes, it becomes evident that owing to the intricate conditions inherent in the actual formation, the natural fissures within the rock mass are notably pronounced, hence contributing to the relatively diminished pre-grouting Vp values. Following the grouting process, the interstices within the rock mass fractures are adequately filled with the infused slurry, culminating in a substantial enhancement of structural integrity and a consequential surge in Vp. Subsequent to coal extraction, the floor undergoes a degree of damage within a defined perimeter, with proximity to the coal seam exacerbating the severity of said impairment, albeit with a marginal upturn in Vp discernible just beyond the affected zone. The elevation in Vp can be attributed to a localized increment in stress within the rock mass bordering the floor’s failure zone. While no discernible macroscopic failure manifests within this segment of the rock mass, the minor fissures undergo closure in response to mining-induced stresses, thereby eliciting a marginal augmentation in the overall Vp.

-

(2)

Transient electromagnetic detection reference

The signal captured by Transient Electromagnetic Method (TEM) encapsulates the comprehensive electrical response across the entire volume of the rock mass. Employing TEM facilitates the detection of the working face along the interior of the groove. Given that the coal seam serves as a high-resistance medium, electromagnetic waves readily traverse through it, thereby rendering the resistance value distinguishable from that of other mediums such as aquifers. Notably, Working Face 11,050 is contiguous to Working Face 11,030. Consequently, the TEM detection outcomes from the adjacent grooving of the upper working face can serve as a benchmark for evaluating the efficacy of grouting reinforcement in this working face. The TEM detection outcomes concerning the bottom plate in the 700–1330 m section of the longitudinal groove of the upper working face, both pre- and post-grouting reinforcement, are depicted in the Fig. 8.

Upon examination of the contour lines depicting apparent resistivity, it becomes evident that the contours of L8 limestone exhibit continuous distribution without discernible low-resistivity anomalies, which suggests a relatively uniform distribution of moisture in the water-rich floor; however, the overall apparent resistivity remains low, signifying a potential risk of water inrush. The grouting reinforcement of the floor rock enhances the continuity of the rock mass and elevates the apparent resistance. Theoretically, post-reconstruction, the mechanical parameters of the rock strata and rock mass undergo varying degrees of augmentation, thereby altering the corresponding theoretical safe water pressure value and ultimate water pressure-bearing capacity of the floor. Consequently, the anticipated decline in the failure depth and water inrush coefficient of the floor is expected.

Water inrush risk evaluation based on acoustic parameter transformation

-

(1)

Calculation method of composite rock floor parameters

The floor rock mass within the stope comprises rock strata of diverse lithology and thickness, exhibiting heterogeneous characteristics, as depicted in Fig. 9. Following the detection of the specific mechanical parameters of each rock layer, a calculation system for key parameters of the multi-rock composite floor must be devised based on the actual occurrence of strata and a guided selection process. Subsequently, an evaluation of the water inrush risk on the grouting face should be conducted.

The average modulus method offers a viable approach for dissecting the mechanical intricacies across multiple strata within coal seam floors. Initially, the average modulus method transmutes individual rock layers into singular rock mass mechanical parameters, veering away from the conventional treatment of each layer as a semi-isotropic homogeneous elastic body. Leveraging a parameter closely linked to a singular attribute, it orchestrates a weighted average of other pertinent physical quantities. Strength values are derived by means of function curves tailored via artificial intelligence prediction methodologies. Subsequently, the rock mass’s strength within the coal seam floor is inferred from the elastic modulus, calculated through sound velocity juxtaposed with lithological attributes. Throughout this computation, thickness serves as the pivotal weight value, guiding the weighting and averaging of floor rock mass strength according to a predefined formula. Subsequently, a secondary round of averaging ensues, incorporating relevant parameters such as bulk density. Ultimately, this process yields a standardized parameter value tailored to the working face, thereby setting the stage for further computations.

$$\overline{{R_{c} }} = \frac{{h_{1} R_{c1} + h_{2} R_{c2} + \cdots + h_{i} R_{ci} + \cdots + h_{n} R_{cn} }}{{h_{1} + h_{2} + \cdots + h_{i} + \cdots + h_{n} }} = \frac{{\sum\nolimits_{1}^{n} {h_{i} R_{ci} } }}{{\sum\nolimits_{1}^{n} {h_{i} } }}$$(11)where \(\overline{{R_{c} }}\) is the weighted average value of compressive strength of floor rock, GPa; \(h_{i}\) is the thickness of the i-th layer, m; \(R_{ci}\) is the compressive strength of the stratum, GPa.

-

(2)

Calculation of water inrush risk assessment index.

Table 2 presents a concise summary of settlement outcomes derived from standard water inrush risk assessment metrics, computed based on the converted strength parameters.

Table 2 Summary of results of water inrush risk assessment index of 11,030 working face.

Through a comprehensive analysis of the data presented in Table 2, we can systematically derive the following conclusions:

Utilizing Formula (5), the failure depth of the coal seam floor is calculated both before and after grouting, yielding depths of 34.1 m and 21.7 m respectively. Concurrently, the ultrasonic wave measurement reveals a failure zone height of 20.8 m, with the ungrouted working face exhibiting a floor failure depth of 32.6 m in the adjacent panel. Remarkably, the strength parameters derived from the new methodology exhibit superior adaptability to fracture mechanics calculations, yielding results that closely align with field measurements, with a negligible 5% calculation error in failure depth.

The water inrush coefficient for the working face is determined by assessing both the maximum water pressure of the aquifer and the actual value of h2. With an average depth of 23.8 m between the L8 limestone aquifer and the coal seam floor, which is shallower than the failure depth of the ungrouted working face floor, it is anticipated that the L8 limestone will inevitably release water post-mining. However, post-grouting, the L8 limestone undergoes a transformation into a relatively impermeable layer, rendering the calculation of the water outburst coefficient unnecessary given the floor’s failure depth. The water inrush coefficients for L2 limestone pre- and post-grouting are 0.106 MPa/m and 0.091 MPa/m respectively, while those for O2 limestone are 0.077 MPa/m and 0.069 MPa/m correspondingly. As per the Water Control Rules, there is a risk of water inrush in L2 limestone pre-grouting, which diminishes post-grouting, ensuring safe mining operations. O2 limestone poses no water inrush threat to the working face both before and after grouting.

According to thin plate theory, the thickness of the safety belt in L8 limestone before and after grouting measures 57.6 m and 43.9 m, correspondingly, exceeding the thickness of the L8 limestone from the coal seam and posing a higher discharge risk. The measured water barrier thickness of L2 limestone before and after grouting amounts to 69.8 m and 81.6 m, respectively, with the pre-grouting thickness of L2 limestone falling below the calculated value of h2s, while post-grouting thickness surpasses h2. Consequently, the analysis of thickness indicates no risk of water inrush in the secure water barrier zone post-grouting transformation. The measured thickness of the O2 limestone zone exceeds the calculated value of h2s, fulfilling water isolation requirements without water inrush hazards.

Both the ultimate hydraulic pressure evaluation method (Pmax) and the theoretical safe hydraulic pressure (Pla) are employed to characterize the resistance of current geological structures to water pressure. L8 limestone lies within the floor’s failure zone, rendering its capacity to withstand water pressure incalculable. Pre- and post-grouting, the ultimate water pressure of L2 limestone measures 6.8 MPa and 7.33 MPa, respectively, below the theoretical safe water pressure value. This evaluation index suggests that despite reconstruction, the rock layer still carries the risk of water outburst, yet the grouting reinforcement project notably enhances the anti-outburst capability of the waterproof rock layer. O2 limestone exhibits an ultimate water pressure value of 9.4 MPa, below the pre- and post-grouting ultimate water pressure of the floor block belt, hence posing no risk of water inrush.

In summary, considering the failure depth of the adjacent ungrouted working face floor, the L8 limestone aquifer resides within the failure zone, posing the highest risk of water inburst on the working face. Before grouting, the water inrush coefficient of structurally unaffected L2 limestone exceeds 0.1, indicating a risk of water inrush. The risk of water inrush in O2 limestone is minimal. Hence, reinforcing the working face through grouting becomes imperative. Consequently, the L8 limestone aquifer at the base of the reinforced working face transforms into a comparatively impermeable layer, eliminating the risk of water inrush within this stratum. Additionally, the risk of water inrush from L2 limestone decreases as the thickness and strength parameters of the water-retaining layer simultaneously increase, enhancing the safety of O2 limestone.

Application II: floor heave analysis of fractured rock mass

Overview of the main belt transportation lane

The belt transportation roadway in the I panel area of Zhaogu No. 2 Mine follows along the coal roof of No. 2-1 coal seam, with a rectangular excavation section featuring a net width and height of 5.48 × 3.89 m. Supporting the main roadway in the panel area involves a combination of anchor rods (cables), W-shaped steel belts, reinforced ladders, and channel steel beams. Secondary support is provided through a combination of anchor cable nets, 12# steel sheds, and shotcrete.

Experimental model and scheme

-

(1)

Numerical model of roadway deformation

The universal distinct element code (UDEC) of discontinuous medium for large deformation31 was selected to analyze the mechanism of action of water pressure and fault to the roadway. According to 12,603 drill borehole (Fig. 5) and water inrush reference24, the belt conveying roadway of the first district (size(W × H): 5.48 × 3.89 m) was choose to study. The design model (Fig. 10) with the size of 80 × 60 m was carefully divided by the physical–mechanical characteristics and thickness of each rock layer to analyze the deformation, yield strength and failure state of the sand body and rock mass in detail. According to the model and current support method of roadway roof, bolt and cable are applied to the roof and two sides of the roadway. In the numerical model, four points (41, 38.5), (42, 38.5), (43, 38.5), and (44, 38.5) are designated as feature points 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, with their displacements recorded throughout the calculation process. These model specifications are detailed in Fig. 10.

-

(2)

Numerical simulation experiment scheme

The primary cause of water inrush in roadway floors is the formation of cracks resulting from the displacement of rock strata, subsequently serving as conduits for water ingress2. Considering the location of the roadway crossing fault, numerical simulations assess the impact of three scenarios on L8 limestone, L9 limestone, and no water pressure conditions. Emphasis is placed on considering the influence of grouting factors, and an orthogonal design evaluates their effects on the experimental outcomes, detailed in Table 3.

Table 3 Numerical simulation experiment scheme.

Boundary conditions and parameter setting

The upper surface of the model is a free boundary, where the uniform vertical compressive stress of 9.8 MPa is applied according to the weight of the overlying rock mass on the stope, and the left and right boundaries are subject to zero displacement boundary conditions. The lower boundary is the fully constrained boundary and water pressure is applied with water density of 1000 kg/m3, the bulk modulus is 2 GPa. The Mohr–Coulomb model is used with a combination of the physical and mechanical parameters of the laboratory rock mass. Combined with the mechanical parameter calculation method in Section “Measurement of rock wave velocity and conversion to elastic modulus”, the model parameters of this study are as follows (Tables 4, 5, and 6):

Analysis of roadway floor displacement

-

(1)

Damage range of roadway floor

Based on the assumption of elastic mechanics on the floor rock beam of the roadway, when there was a fault in floor, it is considered that the rock layer closest to the floor that only produces bending deformation is a cantilever beam. The selected mechanical model is shown in Fig. 11.

Maximum influence depth of stress field in deep mining floor fissure rock mass hp:

$$h_{p} = \frac{{q^{\prime } }}{{2\pi \gamma_{d} }}\left( {\frac{2\sqrt \nu }{{\nu - 1}} - \cos^{ - 1} \frac{\nu - 1}{{\nu + 1}}} \right) - \frac{{R_{c} }}{{\gamma_{d} (\nu - 1)}}$$(12)$$\nu { = }\frac{{\left( {{1} - \sin \,\varphi } \right)}}{{\left( {{1 + }\sin \,\varphi } \right)}}$$(13)With width r of the roadway, the limit equilibrium zone radius R0:

$$R_{0} = r\left[ {\frac{{\left( {\gamma H + C\,\cot \,\varphi } \right)\left( {1 - \sin \,\varphi } \right)}}{C\,\cot \,\varphi }} \right]^{{\frac{1 - \sin \varphi }{{2\sin \varphi }}}}$$(14)The known fault dip θ is 60°, and the asymmetric plastic zone of roadway surrounding rock stress environment on the revised effective cantilever beam L is calculated by the following formula:

$$L = h_{p} \cot \,\theta + 1.31\,R_{0}$$(15)The formula of the movement of the cantilever beam is given in material mechanics:

$$y_{b} = \frac{{qx_{b}^{2} }}{24\,EI}\left( {x_{b}^{2} + 6L^{2} - 4Lx_{b} } \right)$$(16)By substituting the relevant rock mechanical parameters of Zhaogu No. 2 Mine30, the maximum deflection at xb is obtained as yb = 643.8 mm.

-

(2)

Displacement calculation and comparison

To comprehensively analyze the failure behavior of the roadway floor, various variables are defined for expression. The actual floor heave is denoted as W, while in numerical simulations, we represent the floor heave before and after grouting as W′ and W′′ respectively. The distance between the floor and the rock layer, analogous to a cantilever beam, is considered the failure depth of the roadway floor (hp). yx represents the maximum deflection of the cantilever beam at position x, while Δy and Δy′ signify the disparity between the floor heave and the maximum deflection (yx) of the cantilever beam before and after grouting in both engineering practice and numerical simulation. The ratio ε (Eq. 17) is formulated to depict the actual floor failure zone strain in engineering, where ε′ and ε′′ represent the linear strain of floor failure zone before and after grouting in numerical simulation experiments, measured in mm/m. Errors V′ and V′′ serve as parameters to quantify the deviation between numerical simulation experiment analysis and engineering practice.

$$\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {\varepsilon = (W - y_{x} )/h_{p} = (\Delta y)/h_{p} } \hfill \\ {\varepsilon^{\prime } = (W^{\prime } - y_{x} )/h_{p} = (\Delta y^{\prime } )/h_{p} } \hfill \\ {\varepsilon^{\prime \prime } = (W^{\prime \prime } - y_{x} )/h_{p} = (\Delta y^{\prime \prime } )/h_{p} } \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$(17)$$\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {V^{\prime } = \left( {\varepsilon - \varepsilon ^{\prime } } \right)/\varepsilon \times 100\% {\text{ }}} \hfill \\ {V^{{\prime \prime }} = \left( {\varepsilon - \varepsilon ^{{\prime \prime }} } \right)/\varepsilon \times 100\% } \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$(18)The analysis of the influence mode and extent of faults on roadway floor heave has been conducted by incorporating faults into the numerical calculation model, with detailed findings provided in reference2. Schemes d/e/f in literature2 can be adopted as schemes 1/2/3 in this simulation. Additionally, schemes 4/5/6 in the model, combined with the rock mass strength parameters after grouting, could be employed to compare and analyze the floor heave issue before and after grouting of the over-fault roadway.

The formula 14 calculates the failure depth of roadway floor at 9.6 m, and converts the elastic modulus into strength according to the in-situ ultrasonic measurement sound velocity, and obtains the corresponding roadway floor heave W′′ = 630 mm after the reconstruction, which is 560 mm less than that of roadway floor heave W′ with fault before grouting, \(\varepsilon^{\prime \prime }\) = 65 mm/m, and 47% less than that of \(\varepsilon^{\prime }\) before grouting. The factors that cause the variation of floor failure zone strain include floor lithology combination, stress distribution of surrounding rock and deflection of key layer of water barrier. Under the influence of faults, the floor heave of the roadway without grouting increases by an average of 667 mm. Under the combined effect of water pressure on L8 and L9 (Scheme e, Fig. 12), the floor heave of the roadway is 1200 mm, which exceeds the maximum floor heave of the roadway without fault (Scheme b, Fig. 12) by 668 mm, and is 10 mm higher than the maximum floor heave of the roadway when the water pressure is applied to L8 (Scheme d, Fig. 12). It shows that L9 stratum water has little influence on floor heave. When the fault is affected, the displacement difference reaches 680 mm, which provides a water channel for the floor to discharge water.

The floor heave is 2.56 times larger when faults are present compared to when they are not, and the displacement of the upper wall exceeds that of the lower wall. Overall, the floor heave after grouting is approximately 53% of its pre-grouting value, highlighting the significance of floor rock mass structure in floor heave formation, and suggesting that grouting fault reconstruction technology can mitigate the floor heave issue. Furthermore, there exists an error between numerical simulations and actual floor heave, stemming from incomplete understanding of microgeological conditions and fine geological structures.

In summary, the variation of the deflection of the key layer is determined by aquifer water pressure and plastic zone width. In which the greater aquifer water pressure results in increased strain of the failure zone line within a specific plastic zone width. With aquifer position and confined water pressure remaining constant, the linear strain of rock strata in the failure zone correlates positively with the width of the plastic zone. The failure depth of the floor is jointly influenced by the floor structure and surrounding rock stress. When a structural fracture zone exists in the floor, the line strain of the failure zone increases under high surrounding rock stress, making the floor susceptible to water inrush.

Post-reinforcement, the mechanical parameters of rock mass in the rock floor and structural fracture zone are enhanced, improving the water resistance of the rock mass. This effectively reduces the deflection of the plastic zone and the key layer of water insulation in the excavated roadway during use, thereby reducing the risk of water inrush in the roadway.

Conclusion

-

(1)

Utilizing rock mechanics test results from on-site rock samples, combined with existing literature data, we constructed a comprehensive sample library encompassing the elastic modulus (E) and compressive strength (Rc) parameters. Following a comparison of four distinct artificial intelligence parameter prediction methodologies, the K-NN method emerged as the optimal approach. Employing this method, we predicted the compressive strength (Rc) derived from the elastic modulus (E) obtained via acoustic wave data measured in the borehole. This approach facilitated an augmentation in the total number of data samples encompassing both elastic modulus and its corresponding compressive strength.

-

(2)

After organizing the data samples of the artificial intelligence prediction results, we conducted E—Rc relationship fitting using various function types. Subsequently, we compared the concatenated data with the fitting results classified by lithology. Finally, utilizing R2 as the evaluation standard, we determined the fitting function results of the E—Rc relationship, specifically the Logistic type, based on lithology classification of coal measure strata in Zhaogu 2 mine.

-

(3)

The E—Rc relation transformation method is applied to two field projects, focusing on water inrush risk assessment and floor heave analysis of fractured rock mass, respectively. Utilizing the strength parameters of rock mass obtained through fitting functions, we compute four commonly used indexes for evaluating water inrush risk on the working face. Subsequently, we analyze the water inrush risk of L8, L2, and O2 limestone floors before and after grouting based on these indexes. Furthermore, the strength parameters of the roadway floor rock mass before and after grouting are calculated using the E—Rc transformation method. The displacement of roadway characteristic points before and after grouting is then analyzed using the UDEC numerical simulation method. These results validate that grouting reinforcement can serve as an effective means to mitigate roadway floor heave and water inrush under these working conditions.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Mu, W. Q., Li, L. C., Zhang, Y. S., Yu, G. F. & Ren, B. Failure mechanism of grouted floor with confined aquifer based on mining-induced data. Rock Mech. Rick Eng. 56, 2897–2922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-03179-x (2023).

Zhang, E. et al. Influence of the dominant fracture and slurry viscosity on the slurry diffusion law in fractured aquifers. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 141, 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104731 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Study and engineering application on the bolt-grouting reinforcement effect in underground engineering with fractured surrounding rock. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 84, 237–247 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Experimental study on the grouting diffusion process in fractured sandstone with flowing water based on the low-field nuclear magnetic resonance technique. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56, 7509–7533 (2023).

Qian, Q. Some adcances in rock blasting dynamics. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 28, 1945–1968 (2009).

Meng, F. Z., Wong, L. N. Y. & Zhou, H. Rock brittleness indices and their applications to different fields of rock engineering: A review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. 13, 221–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2020.06.008 (2021).

Fathollahy, M., Uromeiehy, A., Riahi, M. A. & Zarei, Y. P-wave velocity calculation (PVC) in rock mass without geophysical-seismic field measurements. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54, 1223–1237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-020-02326-6 (2021).

Mousa, M. A., Yussof, M. M., Hussein, T. S., Assi, L. N. & Ghahari, S. A digital image correlation technique for laboratory structural tests and applications: a systematic literature review. Sensors-Basel 23, 134–146. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23239362 (2023).

Kao, S. M. et al. Dynamic mechanical characteristics of fractured rock reinforced by different grouts. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8897537 (2021).

Ren, B. et al. Investigation of a method to prevent rock failure and disaster due to a collapse column below the mine. Mine Water Environ. 41, 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2020.106931 (2022).

Yesiloglu-Gultekin, N. & Gokceoglu, C. A Comparison among some non-linear prediction tools on indirect determination of uniaxial compressive strength and modulus of elasticity of basalt. J. Nondestr. Eval. 41, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10921-021-00841-2 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Mechanism of water inrush and controlling techniques for fault-traversing roadways with floor heave above highly confined aquifers. Mine Water Environ. 39, 320–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-020-00670-1 (2020).

ASTM. (ASTM, ASTM International, 2022).

Teixeira, L. & Lupinacci, W. M. Elastic properties of rock salt in the Santos Basin: Relations and spatial predictions. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 180, 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2019.05.024 (2019).

Peeperkorn, J., Vanden Broucke, S. & De Weerdt, J. Validation set sampling strategies for predictive process monitoring. Inf. Syst. 121, 23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.is.2023.102330 (2024).

Liu, D., Zhao, Z., Cai, Y. & Sun, F. Characterizing coal gas reservoirs: A multiparametric evaluation based on geological and geophysical methods. Eng. Gondwana Res. 133, 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2024.06.001 (2024).

Jakel, F., Scholkopf, B. & Wichmann, F. A. Generalization and similarity in exemplar models of categorization: Insights from machine learning. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 15, 256–271. https://doi.org/10.3758/pbr.15.2.256 (2008).

Kong, D. P. et al. Self-supervised knowledge mining from unlabeled data for bearing fault diagnosis under limited annotations. Measurement 220, 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2023.113387 (2023).

Zhou, X., Lu, P., Zheng, Z., Tolliver, D. & Keramati, A. J. R. E. S. S. Accident prediction accuracy assessment for highway-rail grade crossings using random forest algorithm compared with decision tree. Syst. Saf. 200, 106931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2020.106931 (2020).

Borji, M., Damaneh, H. E., Pham, Q. B., Linh, N. T. T. & Bach, Q. V. J. G. I. Evaluation of re-sampling methods on performance of machine learning models to predict landslide susceptibility. Geocarto Int. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2020.1837257 (2020).

Baptista, M. L., Goebel, K. & Henriques, E. M. P. J. A. I. Relation between prognostics predictor evaluation metrics and local interpretability SHAP values. Artif. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2022.103667 (2022).

Aboutaleb, S., Behnia, M., Bagherpour, R. & Bluekian, B. J. S. B. H. Using non-destructive tests for estimating uniaxial compressive strength and static Young’s modulus of carbonate rocks via some modeling techniques. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 77, 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-017-1043-2 (2018).

He, K. Q., Guo, L., Guo, Y. Y., Luo, H. L. & Liang, Y. P. Research on the effects of coal mining on the karst hydrogeological environment in Jiaozuo mining area, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 78, 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8456-0 (2019).

Miao, W. et al. The two zones of floor failure and its control via a ‘dual key layer’ approach. Mine Water Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-024-00974-6 (2024).

Zhou, X., Lu, P., Zheng, Z., Tolliver, D. & Keramati, A. J. R. E. S. S. Accident prediction accuracy assessment for highway-rail grade crossings using random forest algorithm compared with decision tree. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 200, 106931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2020.106931 (2020).

Wang, Y. J. P. Destabilization mechanism and stability control of the surrounding rock in stope mining roadways below remaining coal pillars: A case study in buertai coal mine. Processes 10, 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10112192 (2022).

Zhang, H., Wen, Z., Yao, B. & Chen, X. Numerical simulation on stress evolution and deformation of overlying coal seam in lower protective layer mining. Alex. Eng. J. 59, 3623–3633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2020.06.011 (2020).

Zhang, J. & Liu, T. On the depth and distribution characteristics of mining-induced fracture zone in coal seam floor. J. China Coal Soc. 02, 9 (1990).

Sui, W. H., Liu, J. Y., Hu, W., Qi, J. F. & Zhan, K. Y. Experimental investigation on sealing efficiency of chemical grouting in rock fracture with flowing water. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 50, 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2015.07.012 (2015).

He, S. D., Li, Y. R. & Aydin, A. A comparative study of UDEC simulations of an unsupported rock tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 72, 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2017.11.031 (2018).

Li, Y., Ma, N., Ma, J., Zhang, H. & Hao, Z. Surrounding rock’s failure characteristic and rational location of floor gas drainage roadway above deep confined water. J. China Coal Soc. 43, 2491–2500 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ermeng Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Visualization. Lang Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Visualization. Yanchun Xu, Qiang Wu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Visualization. Yu Fei: Investigation. Yabin Lin: Validation. Bo Zhang: Software.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, E., Liu, L., Xu, Y. et al. Conversion, prediction, and application of strength and stiffness parameters for grouted reconstructed rock mass. Sci Rep 14, 29204 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80420-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80420-3