Abstract

Polycrystalline compounds of lanthanum calcium manganite La1 − xCaxMnO3, (LCMO) are extensively utilized in energy conversion systems because of their low losses and features related to the transfer of electric charges. This work aimed to examine the impact of different levels of Ca2+ replacements (x = 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3) on the adjustment of the optical band gap and dielectric losses in La1 − xCaxMnO3 nanoparticles. The synthesized samples underwent structural analysis using X-ray diffraction. All generated samples were proven to have an orthorhombic R\(\bar{3}\)c crystal structure. The estimated crystallite size ranged from 25 nm to 32 nm, and other lattice characteristics were also determined. An agglomerated spherical form consisting of nanoparticles with a range of (33–46 nm) can be seen in the scanning electron micrographs of all of the LCMO samples. The nanoparticles had a moderate size distribution and were influenced by narrower grain boundaries. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy was utilized to verify the elemental makeup of each chemical, while the infrared spectrum revealed bonding in the fingerprint region. A considerable decrease in the optical band gap was detected through the analysis of UV spectrometer absorption data. The band gap exhibited a reduction from 3.95 eV to 3.74 eV. The decrease was determined to be associated with the disparity in refractive index, which was computed using both Moss and Herve-Vandamme equations. Simultaneously, frequency-dependent dielectric study indicated a direct correlation between frequency and the rise in Ca concentration, resulting in an inverse impact on dielectric loss. In addition, the electrical conductivity of these nano-system that were created design as the Ca content grew. This increase was represented by Johnscher’s universal power law in the high frequency range.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scientists have shown increasing interest in researching renewable energy resources in recent years. Utilizing renewable energy resources results in an environmentally clean atmosphere and has a smaller impact on climate change in comparison to the usage of fossil fuels. Diverse materials are produced to convert these energy resources into usable electrical energy. Lanthanum-based ABO3-type perovskite oxide materials have undergone thorough investigation due to their diverse applications in electrical and magnetic storage systems. In the ABO3-type perovskite structure, A represents positively charged cation metals from the rare earth or alkaline earth group, while B represents transition metal cations. The sum of their charges is always 6, as seen in compounds such as A3+B3+O3, A2+B4+O3, or A1+B5+O3. Lanthanum manganite nanoparticles (LaMnO3) possess distinctive optical and electrical characteristics and find extensive utilization in various fields including LiO2 batteries, supercapacitors, photo catalysis, and dye-synthesized solar cells with long-term viability1,2,3,4. Prior research has indicated that LaMnO3 nanoparticles with a high specific surface area have exceptionally strong catalytic activity in the process of oxygen reduction. The presence of oxygen vacancies in the Mn3+-O2−-Mn4+ network leads to the occurrence of oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER)2,5,6, . Substituting either the A or B site in the LaMnO3 system causes a distortion in the octahedral symmetry of MnO6, known as the Jahn-Teller distortion. The distortion of perovskite materials causes a shift from Mn3+ to Mn4+ ions, resulting in improved chemical stability, enormous magnetoresistance, nitrogen monoxide (NO) absorption capacity, and pseudo capacitive performance3,7,8. The manipulation of particle size, electrical conductivity, optical band gap, and dielectric constant can be achieved by partially substituting the divalent cation, such as Ca2+, Sr2+, Ba2+, or Mg2+, with a La3+ ion on the A site in La1 − xAxMnO3 perovskites9,10,11.

Observations over a period of several years have shown that nanoparticles of partially replaced lanthanum magnetite (La1 − xAxMnO3) display electric polarization, this enables the calculation of their permittivity spectrum. This material has a very high dielectric constant (specifically on the order of 105) making it in use for various applications12,13. The optical and dielectric qualities of the material are enhanced by doping with alkaline earth metals, such as Sr2+. Tripathi et al.14 have concluded that the presence of Sr decreases flaws and enhances the optical properties of NiO nanoparticles. Du Huiling et al.15 discovered that the addition of Sr2+ to BST ceramics leads to a decrease in dielectric losses. Kandil et al.16 found that the dielectric constant increased significantly when a larger molar ratio of Sr2+ was used in BST nanoparticles. Transition metals, including manganese (Mn), have a crucial function in facilitating charge transport during a transition process when Sr2+ (1.44 Å) is partially replaced by La3+ (1.36 Å)17. This transition leads to enhanced electrical characteristics that are associated with reduced dielectric losses in the required material. The motion of these charge particles can be demonstrated via tunneling and hooping processes18,19. In polycrystalline material, at relatively high frequency, charge particles undergo a phenomenon called hooping, where they transition between localized states across grain boundaries. This process can effectively minimize defects in the material. The density of a material can lead to a boost in its AC conductivity20. According to reports, when an electric field originating from an external source is applied, charge particles accumulate at the boundaries between grains in the material. The concentration of charges in the material results in polarization, which subsequently enhances the dielectric constant and total AC conductivity of the doped material21,22. Ali Omar Turky and his colleagues did a study in which they created LSM nanoparticles with varying composition of x (0.2, 0.5, and 0.8) utilizing precipitation and citrate precursor procedures23. They found that as the dielectric constant decreased, there was an increase in the optical band gap for higher values of x24. According to Andreja Žužić et al.25, LSM nanoparticles made ready by the co-precipitation method have higher electrical conductivity. Sandhya Suresh et al.24 a range of LSM nanoparticles were synthesized for various x values (0.0, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7) using combustion. A higher band gap was seen in the presence of a falling refractive index and falling dielectric losses. The primary focus of this study was the x = 0.7 sample. Despite relatively small dielectric losses, the authors found a dramatic increase in the dielectric constant. This could be attributed to the presence of extensive grain boundaries that experience greater strain due to the Mn4+ ions occupying lattice positions. Significant research has been carried out on LSM nanoparticles, which has led to a reduction in the existing research gap. In this study, our research reveals that a variety of stable nanoparticles exhibit a decrease in losses as a function of band gap of La1 − xCaxMnO3, where x = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 these nanoparticles were produced using the precipitation method.

In order to prevent the production of the low conducting SrZrO3 phase, in the La1 − xCaxMnO3 lattice, we utilized Ca ion molar ratios of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 to attain a rather high conducting phase. According to a report, samples made using the precipitation process exhibit better conductivity. Specifically, at ambient temperature, a conductivity of 0.176 Ω−1∙cm− 1 was obtained with a 20% Sr2+ content. This conductivity is similar to that of silicon25. The inclusion of the hooping mechanism at the octahedral site in the La1 − xCaxMnO3 system greatly affects the modification of optoelectrical properties, such as the optical band gap, refractive index, frequency-dependent dielectric constant, dielectric losses, and AC conductivity. These properties are greatly influenced by the degree of substitution, lattice misfit, and grain size.

An experimental attempt has been made to address the discrepancies between the structural, dielectric and optical characteristics. In the current study, we concurrently doped Ca ions into La1 − xCaxMnO3 to modify the host LaMnO3 lattice’s structures and crystalline characteristics in order to get the optimal optical and dielectric response for upcoming applications. One of the most significant results of the present study is that Ca doping reduces the band gap of the La1 − xCaxMnO3 nanostructure from 3.95 eV to 3.74 eV. The Ca doping is attributed to an increase in Mn3+/Mn4+, which produce hooping, and is present at all doping concentrations. The dielectric properties, which are significantly influenced by frequency, decrease as AC conductivity increased with an excess of polarons in the heavy-doped sample. Ca doping has been found to be a helpful technique for adjusting the characteristics of La1 − xCaxMnO3 nanoparticles for potential to serve in energy storage devices and high frequency transmission cables.

Experimental techniques

In the present study, we have used the precursor with a purity level of 99.95%, which includes calcium chloride dihydrate [CaCl2.2H2O], manganese nitrate tetra hydrate [Mn(NO3)3.4H2O], and lanthanum (III) nitrate hexahydrate [La (NO3)3.6H2O]. Sigma-Aldrich provided sodium hydroxide (NaOH) as a precipitating agent. All the substances were used in their original form as obtained directly from the supplier without any further purification.

Sample preparation

The initial solution was agitated at a constant temperature of 80 °C for a duration of 2 h to ensure uniformity and the full progress of the reaction. In order to keep the pH level at 8.5, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was added gradually, one drop at a time. The solid formed was separated by filtration and allowed to reach the ambient temperature. The LCMO nanoparticles were prepared by dispersing the powder in ethanol using ultrasonic waves for a duration of 15 min. Subsequently, the nanoparticles were separated and cleansed by centrifugation and washing with distilled water. Subsequently, the material was subjected to a drying process in an oven at a temperature of 100 °C for a duration of 1 h. The dried samples were subjected to annealing in a furnace for a duration of 8 h at a temperature of 800 °C. A same technique was employed for all samples.

Structural and optical characterization techniques

The materials underwent examination utilizing X-ray diffraction (XRD) through the utilization of a Diffractometer system known as XPERT-3, developed by Malvern Panalytical. The analysis was conducted using Cu K-alpha radiation with a wavelength of 1.54 A°. The angular range of 20º ≤2θ ≤ 70º was scanned in steps of 0.02°, with each step taking 3 s to count. The samples’ morphology was assessed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM-VEGA 3 TESKAN). The chemical composition was determined using an Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometer (EDX) that was connected to the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). The identification of functional groups was performed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) with the IRTracer-100 SHIMADZU instrument, covering a wavelength range of 400 to 4000 cm− 1. The optical properties of the materials were analyzed using a UV-Visible spectrometer (SPECORD 200 PLUS). The sample’s ac conductivity and dielectric properties were evaluated within the frequency range of the impedance analyzer, utilizing a gold terminal pellet spanning from 1 Hz to 1 MHz.

Results and discussions

Structural analysis

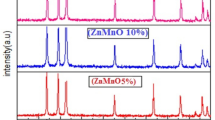

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) profiles of all the samples that were prepared showed that they were composed of pure La1 − xCaxMnO3 (0.1 ≤ x ≤ 0.3) polycrystalline nanocrystals. The samples were synthesized using the co-precipitation method and then subjected to calcination at a temperature of 800 °C for a duration of 8 h. Following the calcination process, the samples were cooled to room temperature, as depicted in Fig. 1. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns for all compositions showed a single-phase crystal structure with no further impurities. The samples have an orthorhombic crystal structure (R\(\bar{3}\)c − spacegroup). The lattice constants were confirmed using the Xpert high score program, with reference (JCDPS No 89–0662) for each composition of Ca2+. This is in line with previously published data25.

In order to guarantee the purity of the sample phase, we conducted step scanning at room temperature along the angular range of 22.5° < 2 theta < 58.7°. Figure 3.1 indexes peaks based on the electron density of the material at various diffraction angles. The average crystallite size (D) was determined using Debye Sherrer’s equation:

where D denotes the size of the crystallite, λ represents the wavelength of X-rays, θ represents the Bragg diffraction angle, and β indicates the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak27,28.The average size of the crystallites varied from 25 to 32 nm, indicating the level of crystallinity in the produced samples29. The calculated lattice constant suggested anisotropic behavior with unit cell volume, which can be attributable to two main reasons. The replacement of a comparatively larger Ca2+ ion (1.54 Å) with a coordination number of 12 may have resulted in the oxidation of some Mn3+ ions to Mn4+ ions, which have smaller ionic radii25. This oxidation may lead to a reduction in the size of the unit cell. Additionally, the presence of empty spaces at oxygen sites may have played a role in diminishing electrostatic forces, resulting in a decrease in the volume of the unit cell. The lattice constants determined for orthorhombic with a hexagonal morphology are connected to the unit cell volume as described by Eq. (2).

Where a and c are lattice constants24. It has been noticed that the presence of Ca2+ in host lattice La1 − xCaxMnO3 decreases the dislocation density (defects per unit volume); this can be defined in terms of interims of crystallite size as:

The results of Eq. (3)31 validated that the intended samples exhibited enhanced crystallinity when the defect rate decreased from 0.0044 to 0.0025. This improvement renders them more appropriate for storage applications. The optoelectrical properties of the dopant atoms were analyzed by estimating the macro strain, X-ray density, and specific surface area. The findings of this analysis are discussed in later parts. Therefore, Eqs. (4), (5), (6) were utilized to calculate the micro-strain, X-ray density, and specific surface area, which can be stated as40,41,42:

and

Equation (5) defines ρx−ray as the X-ray density, which is determined by factors such as molecular weight, coordination number, Avogadro’s number, and unit cell volume. All crystallographic data findings are presented in Table 1. The Jahn-Teller distortion in MnO6 is a significant factor in altering the lattice characteristics, resulting in improved electrical properties by creating more vacancies through the Mn3+ to Mn4+ transitions.

Morphological studies

Figures 2, 3 and 4 shows the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) characterization of the morphology and particle size of the obtained sample La1 − xCaxMnO3 (x = 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3) that was annealed at 800 °C for 8 h. The annealed samples consist of microscopic particles with uneven shapes that tend to aggregate, as observed in the SEM images. The particle size was judged to be within the range of 68, 83, and 102 nm, based on the smallest particles observed in the SEM image shown in Table 2. The image depicts a particle that is agglomerated and has a hexagonal surface morphology. The particle size determined by SEM is reasonably consistent with the calculated 20 nm crystallite size derived from the XRD pattern. Particle agglomeration causes a little increase in the observed particle size compared to the estimated crystallite size determined by the XRD pattern. The samples have a hexagonal surface shape. The increase in Ca concentration leads to an observable enlargement in particle size, as evidenced by the SEM images. This substitution induces the formation of oxygen vacancies, hence promoting the conversion of Mn3+ to Mn4+. The nanoparticles’ single crystalline structure is confirmed by the unique pattern.

Compositional analysis

The elemental composition and phase purity of La1 − xCaxMnO3 (x = 0.1, 0.2, or 0.3) are verified by the detection of peaks corresponding to La, Mn, O, and Ca in the EDX spectra, as shown in Fig. 5. No more peaks related to impurities are seen. The atomic proportions of La, Ca, Mn, and O detected in the EDX spectra closely correspond to the initial values used in the synthesis process. The initial values used in the synthesis process and the atomic weight percentages of the elements used, as obtained from the EDX spectrum, were highly consistent. Table 3 presents the weights and atomic percentages of the samples. The produced nanoparticles displayed an excess of oxygen and a composition that was almost stoichiometric32.

FTIR analysis

We have used the FTIR technique to evaluate the material. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is a technology that allows us to analyze the bonding of a material as shown in Fig. 6. The FTIR measurements provide information about the chemical bonds between atoms and molecules. We have conducted FTIR measurements on our three materials and observed that atoms and molecules may create connections via several methods, including stretching, bending, and rocking. The picture shows that the stretching vibrations of Mn-O bonds are connected to the range of 690 to 710 cm⁻¹, whereas the bending modes of Mn-O bonds are related with the range of 465 to 480 cm⁻¹ (34). This correlation is due to a change in the bond angle of Mn-O-Mn. The bending mode is associated with a modification in the Mn-O-Mn bond, while the stretching mode is connected to internal motion and a variation in the bond’s length. The Mn-O-Mn stretching modes exhibit lower wave numbers, whereas the Mn-O-Mn bending vibrations occur at higher wave numbers, as shown by the energy relation expressed by the Eq. (7).

The symbol “h” represents the Plank’s constant, “E” represents the photon energy, and “v” represents the wavenumber. Through the introduction of Ca into pure LaMnO3, we see a significant increase in the absorbance peak at 898 cm⁻¹, which corresponds to the La-Ca bond. The additional peaks seen at 1496, 1498, 1690, 1552, 1556, and 1760 cm-1 may be attributed to the presence of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). The peak seen at 2345–2470 cm⁻¹ is present under normal environmental circumstances and is also found at 3645–3657 cm-1 owing to the presence of water absorbed on the surface of LCMO particles34.

Optical characteristics

Optical studies of the substance have typically controlled the electromagnetic wave interaction between the electric field and the solid. UV-visible absorption spectroscopy is a widely used method for assessing the optical properties of semiconductors. Several factors, such as band gap, oxygen deprivation, surface roughness, and impurity centers, might potentially influence absorbance. The figure illustrates the UV visible absorbance spectra of La, Ca, and MnO samples with varying values of x (0.1, 0.2, and 0.3) throughout the wavelength range of 250–350 nm is shown in Fig. 7. The optical edge of LaMnO3 is measured at 315 nm14, but for Ca doped samples with x values of 0.2 and 0.3, it is found to be in the range of 310–311 nm, indicating a reduction in the optical edge. This optical transition is likely caused by the electronic transition of “Mn” and “O” ions in the orthorhombic structure of LCMO.

The band gap of the samples is calculated using the Tauc’s relation, as shown in Eq. (8).

Where C is a constant, hv represents the photon energy, the values of n = 1/2,3/2 and 2, and 3 is an index dependent on the type of electronic transition that caused the absorption, and is referred to as an absorption coefficient computed as follows25,35.

The variable‘d’ represents the cuvette’s thickness, whereas ‘A’ represents the absorbance. Plots correlating the direct transition between (ahv) and photon energy (hv) are generated to determine the band gap of the samples. These plots are shown in Fig. 8. The calculated optical band gap value and refractive index of each sample are presented in Table 4. The refractive index of each sample was determined using the following equation36.

The values of A and B are constants, with A being 13.6 eV and B being 3.4 eV. Increasing the quantity of Ca doping in LCMO leads to a reduction in the band gap. The reduction of the band gap may be attributed to the quantum confinement effect of the samples. Equation-11 demonstrates the relationship between the average particle size (R) and the effective band gap (E*) of the particles33.

In this context, "me" and "mh" denote the effective masses of electrons and holes, respectively, while "\(E_g^{bulk}\)" represents the band gap energy of the sample in its bulk form. The symbols ε and εo , denote the relative permittivity and the permittivity of free space, respectively. The relationship between the change in band gap energy and the ratio of Mn/Mn as a function of the La/Ca ratio has been established based on the chemical equation La3+(1-x) Ca2+x Mn3+ Mn4+x O331.

Dielectric properties

In the following section, we aimed to establish several significant relationships, primarily the static and high-frequency dielectric constants related to optical behavior. In this context, we utilize this momentum to explain how different AC electric fields affected the La1 − xCaxMnO3 electric dipoles for x = 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3. The properties of the dielectric were assessed using an impedance analyzer with a frequency range of 1 Hz to 1 MHz. The specimen powder was crushed with a force of 10 tons for 10 min, resulting in a pellet with a diameter of 12.7 mm and a thickness of 1.5 mm. The sample acted as the dielectric medium, while the pellets served as the electrodes. Silver paste was applied to both sides of the pellets. The electrodes were connected using ohmic contacts made of slender copper wire. Sandhya Suresh et al. (2023)26 state that complex dielectric permittivity, expressed as \(\:{\mathcal{E}}^{*}\) = ε′ + ε″,can describe how a material behaves when subjected to an external electric field. Here, the real part of the dielectric constant is denoted by ′, which determines the storage of electrical energy, while ″ represents the imaginary part of the dielectric constant, which describes the dielectric loss or the dissipation of energy as heat in the material. The real part of the dielectric can be expressed as in Eq. (12):

The above equations were used to determine the dielectric constant based on measurements of capacitance, dielectric loss, and the size of the pellet (area and thickness). Here, ‘A’ represents the area of the pellet in square meters, while ‘C’ denotes the capacitance, and ‘d’ indicates the thickness of the sample, respectively. Figure 9a illustrates the correlation between the dielectric constant and frequency (f) for LCMO nanoparticles of varying compositions (x = 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3) at a temperature of 300 K. The dielectric constant εr decreases with increasing frequency for all specimens, as indicated by the graph of εr vs. ƒ. At low frequencies, there is a rapid decrease that follows an exponential pattern, but at high frequencies, it shifts to a consistent trend that is not influenced by frequency.

The lower frequency and higher dielectric constant can be attributed to several factors, including interfacial dislocations, charge defects, oxygen vacancies, grain boundary effects, and interfacial/space charge polarization. These factors stem from the heterogeneous nature of the dielectric material. The Maxwell-Wagner model suggests that a dielectric material comprises grains with high conductivity and grain boundaries with low conductivity. Charge carriers can easily move across the grains and accumulate at the grain boundaries due to the influence of an external field. The movement of charged particles within individual grains and the accumulation of electric charge at the boundaries between grains, resulting from the applied electric field, are additional factors that contribute to significant polarization and a high dielectric constant. At higher frequencies, many polarization processes cease because the dipoles do not respond as quickly as the applied field. As a result, the dielectric constant decreases at higher frequencies. To achieve electrical equilibrium, Mn3+ ions oxidize to become Mn4+ ions, while La3+ ions reduce to form Ca2+ ions. The electron hopping between Mn4+ and Mn3+ significantly influences intrinsic dipole polarization, leading to an increase in the local displacement of charge carriers. The dielectric constant decreases as the concentration of Ca2+ ions increases due to the movement of charge carriers from grains that accumulate at grain boundaries. The reduction in grain growth, constrained by insulating grain boundaries, is indicated by an increase in the dielectric constant. An increase in the static dielectric constant suggests that more charge is introduced at the grain boundaries, raising the Ca concentration to enhance the material’s capacity to store electrical energy. However, the drop in band gap from 3.95 to 3.74 eV, as shown in Table 3, can be attributed to the more conducting grain in the sample with x = 0.2, indicating the conductive behavior of the material. A possible cause for the rise in the dielectric constant is an increase in particle size, particularly in the low-frequency range, and a reduction in imperfections and porosity as a result of space charge polarization-induced increases in Ca content37,38,39,40. Due to their exceptionally high static dielectric constant, these materials are utilized in storage devices such as supercapacitors (Sandhya et al., 2023). The nanoparticles of La1 − xCaxMnO3 (with x values of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3) exhibit a frequency-dependent dielectric loss across the frequency range of 1 Hz to 1 MHz at ambient temperature, as illustrated in Fig. 9b. This reveals the energy dissipation caused by voids/defects or dislocation density present in the prepared LCMO nanoparticles. The increase in dielectric loss is evident in the low frequency range of 3.0 log (ƒ) to 5.0 log (ƒ); this steadily decreases with rising frequency (> 5.0 log (ƒ)), indicating the polar nature of the materials. The \(\:\mathcal{E}^{\prime\prime\:}\) vs. ƒ curve can be assessed in light of the material’s polarization mechanism. Typically, the accumulation of charges across grain boundaries is represented by high and low levels of dielectric loss; initially, electric dipoles maintain their orientation according to the polarity of an AC electric field, corresponding with space charge polarization (SCP). In the second half, they are unable to prevent charge carriers from moving across grain boundaries, resulting in leakage or conduction of current in the materials. The relationship between polarization and the energy a dielectric medium loses in an applied field is expressed in Eq. 13.

Where ω is the angular frequency\(\:\mathcal{\:}\mathcal{E}\mathcal{{\prime\:}}\mathcal{{\prime\:}}\) for La1 − xCaxMnO3 nanoparticles represents the dissipation of energy, and E is the electric field vector26. Due to the low reactance of the applied field, conductive loss is relatively low at high frequencies; low-frequency dielectric loss may decrease with increasing Ca2+ dopant concentration due to their ability to modify their domain walls, which are influenced by defect dipoles41. The tangent or dielectric loss can be computed from Eq. (14):

Here \(\:{\mathcal{E}}^{{\prime\prime\:}}and\:{\mathcal{E}}^{{\prime\:}}\) are the imaginary and real parts of the dielectric26. Generally, the restricted motion of domain barriers is expressed by the energy required to exchange electrons between ions. Calcium has been found to reduce defects, and inhomogeneity significantly impacts dielectric loss. As previously mentioned in relation to the XRD data, the energy needed to exchange electrons between Mn3+ and Mn4+ decreases as the molar ratio of Ca2+ increases; this approach reduces losses in the reported samples and suppresses the optical band gap. This disparity can also be explained in terms of particle size37,38, with significantly larger particle sizes resulting in less resistant grains. In the current situation, doping with Ca has led to an increase in particle size, which has decreased the band gap, dielectric loss, and inhomogeneity/defects, indicating that these materials are ideal for photovoltaic and energy storage systems. Figure 9c shows the AC conductivity of La1 − xCaxMnO3 (x = 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3) manganite perovskite oxide nanoparticles as a function of frequency. The frequency-dependent and independent regions of this curve result from the polarity of dielectrics; high resistive grain boundaries that prevent charge carriers from tunneling may cause the lower AC conductivity. Ahmad Gholizadeh et al.39 revealed in their research that interfacial polarization is the cause of this poor conductivity behavior. Similarly, at high frequencies (> 4.0log(ƒ)), a notable increase in conductivity was observed due to the reduced number of grains in the reported samples43. A significant relaxation was noted in the x = 0.1 samples, indicating relatively greater conduction. The angular frequency or leakage current of the sample can be linked to its AC conductivity, as follows:

where the dielectric loss is represented by \(\:\mathcal{E}\mathcal{{\prime\:}}\) and the angular frequency ω may be referred to as leakage current, respectively. The sample’s flat response in the low-frequency region can be attributed to the DC component of conductivity. Low conductivity and ion accumulation at low frequencies are caused by the delayed periodic reversal of the electric field. Frequency-dependent AC conductivity is best described by Johnscher’s universal power law31. The use of Ca2+ as a dopant is crucial for enhancing the AC conductivity of LCMO nanocrystals by providing donor states with an excess of polarons; this reduces defects/inhomogeneity and the porosity of the material (28). Similarly, Ahmad Gholizadeh et al.43 incorporated various dopants in MFe12O19 (M = Ba, Pb, Sr) and examined ƒ-dependent AC conductivity; they found that the Sr-doped sample exhibited higher conductivity due to the presence of highly conductive grains in the materials. Equation 16 illustrates the conduction mechanism in La1 − xCaxMnO3 and connects the host-lattice defects to the partial replacement of Ca2 + ions for charge transfer, while hopping over disordered arrangements with charged carriers:

where ω represents the angular frequency, ωH is the hopping frequency, and s is an exponent of ƒ that can be determined based on the δac vs. frequency plot shown in Fig. 9c by fitting the linear sections. According to one study, electrons in a high-frequency region can hop around two ions with less energy required37. In the La1 − xCaxMnO3 system, a higher Ca2+/La3+ ratio provides more vacancies due to the interaction of charge carriers in O2− and Mn3+, enhancing the movement of electrical charges across smaller grain boundaries, resulting in larger particle sizes. Although tunneling through such small grains is facilitated by the mobility of carriers in the doped samples, which leads to a reduced energy requirement for the exchange between Mn3+ and Mn4+ ions, the hopping mechanism defines the fundamental nature of AC conductivity in the material. The frequency-dependent response of AC conductivity is corroborated by all of the study’s findings, primarily due to the optical band gap, structural defects, and particle size. This suggests that photovoltaic and solid oxide fuel cell applications are the most suitable uses for this material.

Conclusion

The co-precipitation method is a straightforward yet effective procedure for producing LCMO nanoparticles. The XRD data indicate that the samples generated consist solely of one phase and that the addition of dopants does not alter the orthorhombic crystal structure of the R 3 ̅c − space group (167). Increasing the molar ratios of Ca2+ ions led to the enlargement of the crystallite sizes of the produced nanoparticles. The presence of a nano-crystalline structure in the LCMO system is confirmed by the particle size determined through SEM. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the powder samples revealed that the microstructure comprised agglomerated nano-powders, which were small particles arranged in hexagonal clusters. The microstructure was influenced by the concentration of the Ca2+ ion, with clumping increasing as the concentration of Ca2+ ions rose. The produced nanoparticles demonstrate favorable optical absorbance within the wavelength range of 200–800 nm. According to the optoelectrical characteristics of Ca-doped samples, the optical band gap decreased from 3.95 to 3.74 eV due to the elevation of donor states near the conduction band being suppressed, and Moss’s relation indicates an increase in the refractive index from 2.10 to 2.15, suggesting that the samples became more optically dense with higher Ca content. As the Ca content increased, the static and frequency-dependent dielectric constant also increased, indicating that the presented samples are suitable for use in high-frequency transmission cables and energy storage devices due to their low dielectric losses. Ultimately, an excess of polarons in the heavily doped sample resulted in an increase in AC conductivity. Considering the aforementioned factors, it can be concluded that LCMO nanoparticles with lower Ca concentration exhibit greater stability and show promise as materials for electronic storage devices, supercapacitors, and solid-state applications.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Hernández, E., Sagredo, V. & Delgado, G. E. Synthesis and magnetic characterization of LaMnO3 nanoparticles. Rev. Mex física 61(3), 166–169 (2015).

Li, S. et al. Effect of sintering temperature on structural, magnetic and electrical transport properties of La0.67Ca0.33MnO3 ceramics prepared by plasma activated sintering. Mater. Res. Bull. 99, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2017.10.049 (2018).

Shafi, P. M., Joseph, N., Thirumurugan, A. & Bose, A. C. Enhanced electrochemical performances of agglomeration-free LaMnO3 perovskite nanoparticles and achieving high energy and power densities with symmetric supercapacitor design. Chem. Eng. J. 338, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.01.022 (2018).

Özkan, Ç., Türk, A. & Celik, E. Synthesis and characterizations of LaMnO3 perovskite powders using sol–gel method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 32(11), 15544–15562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-021-06104-0 (2021).

Miao, H. et al. A-site deficient/excessive effects of LaMnO3 perovskite as bifunctional oxygen catalyst for zinc-air batteries. Electrochim. Acta 333, 135566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135566 (2020).

Yan, Z. et al. Electrodeposition of (hydro) oxides for an oxygen evolution electrode. Chem. Sci. 11, 10614–10625. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0sc01532f (2020).

Hu, J., Zhang, L., Lu, B., Wang, X. & Huang, H. LaMnO3 nanoparticles supported on N doped porous carbon as efficient photocatalyst. Vacuum 159, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2018.10.021 (2019).

Flores-Lasluisa, J. X., Huerta, F., Cazorla-Amorós, D. & Morallón, E. Manganese oxides/LaMnO3 perovskite materials and their application in the oxygen reduction reaction.Energy 247 (2022), 123456.doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.123456 (2022).

Solopan, S. O., V’yunov, O., Belous, A., Polek, T. & Tovstolytkin, A. Effect of nanoparticles agglomeration on electrical properties of La1-xAxMnO3 (A = Sr, Ba) nanopowder and ceramic solid solutions. Solid State Sci. 14(4), 501–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2012.01.030 (2012).

Zhong, W., Au, C. T. & Du, Y. W. Review of magnetocaloric effect in perovskite-type oxides. Chin. Phys. B 22, 057501. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1056/22/5/057501 (2013).

Afify, M. S., Faham, E., Eldemerdash, M. M., Rouby, U. E. & El-Dek, S. W. M., and Room temperature ferromagnetism in Ag doped LaMnO3 nanoparticles. J. alloys Compd. 861 (2021), 158570. doi: (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020

Assoudi, N. et al. Physical properties of Ag/Ca doped Lantanium manganite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 29, 20113–20121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-018-0143-5 (2018).

Mleiki, A. et al. Magnetic and dielectric properties of Ba-lacunar La0. 5Eu0. 2Ba0.3MnO3 manganites synthesized using sol-gel method under different sintering temperatures. J. Magnetism Magn. Mater. 502, 166571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2020.166571 (2020).

Naseem Siddique, M., Ahmed, A. & Tripathi, P. Enhanced optical properties of pure and sr doped NiO nanostructures: a comprehensive study. Optik 185, 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.03.150 (2019).

Arshad, M. et al. Fabrication, structure, and frequency-dependent electrical and dielectric properties of Sr doped BaTiO3 ceramics. Ceram. Int. (2020).

Turky, A. O. & Kandil, A. T. Optical and electrical properties of Ba1 – xSr x TiO3 nanopowders at different Sr2 + ion content. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 24, 3284–3291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-013-1244-9 (2013).

Xia, W., Li, L., Wu, H., Xue, P. & Zhu, X. Structural, morphological, and magnetic properties of sol-gel derived La0.7Ca0.3MnO3 manganite nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 43, 3274–3283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.11.160 (2017b).

Lu, A. H., Salabas, E. E. L. & Schüth, F. Magnetic nanoparticles: synthesis, protection, functionalization, and application. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 1222–1244. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200602866 (2007).

Li, C., Yu, Z., Liu, H. & Chen, K. High surface area LaMnO3 nanoparticles enhancing electrochemical catalytic activity for rechargeable lithium-air batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 113, 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2017.10.039 (2018).

Tank, T. M., Bodhaye, A., Mukovskii, Y. M. & Sanyal, S. Electrical transport, magnetoresistance and magnetic properties of La0. 7Ca0. 3MnO3 and La0.7Ca0. 24Sr0. 06MnO3 single crystals, in AIP conference proceedings (AIP Publishing LLC), 100027. (2015).

Mohanty, D., Satpathy, S. K., Behera, B. & Mohapatra, R. K. Dielectric and frequency dependent transport properties in magnesium doped CuFe2O4 composite. Mater. Today Proc. 33(2020), 5226–5231. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.944 (2020).

Mohanty, D. et al. Investigation of structural, dielectric and electrical properties of ZnFe2O4 composite. Mater. Today Proc. 33, 4971–4975. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.827 (2020).

Turky, A. O., Rashad, M. M., Hassan, A. M., Elnaggar, E. M. & Bechelany, M. Tailoring optical, magnetic and electric behavior of lanthanum strontiummanganite La1-x SrxMnO3 (LSM) nanopowders prepared via a co-precipitation method with different Sr 2 + ion contents. RSC Adv. 6 (22), 17980–17986. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra27461c (2016).

Turky, A. O., Rashad, M. M., Hassan, A. M., Elnaggar, E. M. & Bechelany, M. Optical, electrical and magnetic properties of lanthanum strontium manganite La1-x srx MnO3 synthesized through the citrate combustion method. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19 (9), 6878–6886. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6cp07333f (2017).

Žužić, A., Ressler, A., Šantić, A., Macan, J. & Gajović, A. The effect of synthesis method on oxygen nonstoichiometry and electrical conductivity of Sr-doped lanthanum manganites. J. Alloys Compd. 907 (2022), 164456. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2022.164456 (2022).

Sandhya, S., Vindhya, P. S., Devika, S. & Kavitha, V. T. Structural, optical and dielectric properties of nanostructured La1 – xSrxMnO3 perovskites. Mater. Today Commun. 36, 106657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106657 (2023).

Safeen, A. et al. The effect of Mn and Co dual-doping on the structural, optical, dielectric and magnetic properties of ZnO nanostructures. RSC Adv. 12, 11923–11932. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ra01798a (2022a).

Safeen, A. et al. Enhancing the physical properties and photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles via cobalt doping. RSC Adv. 12, 15767–15774. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ra01948e (2022b).

Asghar, G. et al. Enhanced magnetic properties of barium hexaferrite. J. Elec Materi 49, 4318–4323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-020-08125-7 (2020).

Shkir, M. et al. A facile microwave synthesis of Cr-doped CdS QDs and investigation of their physical properties for optoelectronic applications. Appl. Nanosci. 10, 3973–3985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13204-020-01505-9 (2020a).

Chandekar, K. V., Shkir, M., Khan, A. & AlFaify, S. An in-depthstudy on physical properties of facilely synthesized Dy@CdS NPs through microwaveroute for optoelectronic technology. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 118, 105184doi. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2020.105184 (2020).

Jadhav, S. V. et al. PVA and PEG functionalised LSMO nanoparticles for magnetic fluid hyperthermia application. Mater. Charact. 102, 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2015.03.001 (2015).

Hassan, A. A. S., Khan, W., Husain, S., Dhiman, P. & Singh, M. Investigation of structural, optical, electrical, and magnetic properties of Fe-doped La0. 7Sr0. 3MnO3 manganites. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 17(5), 2430–2438. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijac.13540 (2020).

McBride, K. et al. Evaluation of La1-xSrxMnO3 (0 ≤ x < 0.4) synthesised via a modified sol–gel method as mediators for magnetic fluid hyperthermia. CrystEngComm 18(3), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ce01890k (2016).

Zhoua, H., Kea, J., Xua, D. & Liub, J. MnWO4 nanorods embedded into amorphous MoS microsheets in 2D/1D MoS/MnWO4 S–scheme heterojunction for visible-light photocatalytic water oxidation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 136, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2022.07.021 (2023).

Gouider Trabelsi, A. B. et al. A comprehensive study on co-doped CdS nanostructured films fit for optoelectronic applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 21, 3982–4001. e4001 (2022).

Eghdami, F. & Ahmad, G. A correlation between microstructural and impedance properties of MnFe2-Co O4 nanoparticles. Phys. B. 650, 414551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2022.414551 (2023).

Mojahed, M., Dizaji, H. R. & Gholizadeh, A. Structural, magnetic, and dielectric properties of Ni/Zn co-substituted CuFe2O4 nanoparticles. Phys. B 646, 414337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2022.414337 (2022).

Gholizadeh, A. & Banihashemi, V. Effects of Ca–Gd co-substitution on the structural, magnetic, and dielectric properties of M-type strontium hexaferrit. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.1919 (2021).

Tarnack, M., Czaderna-Lekka, A., Wojnarowska, Z., Kaminski, K. & Paluch, M. Nature of dielectric response of phenyl alcohols. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 6191–6196. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.3c02335 (2023).

Sun, X. et al. The effect of mg doping on the dielectric and tunable properties of Pb0.3Sr0.7TiO3 thin films prepared by sol–gel method. Appl. Phys. A 114(3), 777–783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-013-7645-z (2014).

Ahmad, G. & Beyranvand, M. Investigation on the structural, magnetic, dielectric and impedance analysis of Mg0.3-xBaxCu0.2Zn0.5Fe2O4 nanoparticles. Phys. B 584, 412079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2020.412079 (2020).

Amini, M. & Ahmad, G. Shape control and associated magnetic and dielectric properties of MFe12O19 (M = ba, Pb, Sr) hexaferrites. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 147, 109660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2020.109660 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-72).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.A: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–reviewand editing. WS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing–review and editing, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation. SK: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–reviewand editing. AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing–review and editing. MMH: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. ZMElB: Investigation, Writing–review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, L., Shah, W.H., Khan, S. et al. Tuning of the band gap and suppression of metallic phase by ca doping in La1 − xCaxMnO3 manganite nano-particles. Sci Rep 15, 44062 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80429-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80429-8