Abstract

Digital health tools are emerging as a promising solution for optimizing Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) therapy for neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s Disease (PD), addressing challenges of therapy maintenance, care access, and discrete assessments. Wearable technology and mobile health platforms can offer remote monitoring capabilities, allowing for real-time virtual programming with optimization of patients’ therapy, use of digital biomarkers that can help identify the onset, symptoms, medication-related fluctuations and side-effects, and response to DBS treatment. Through an investigational remote monitoring application (RM app) integrating patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and objective data using wearables, we aimed to develop an accessible, data-driven digital tool to monitor patient symptoms and deliver low-burden and easy-to-access DBS therapy. The platform is designed to be compatible with several consumer-grade wearables and ensures patient data privacy and security. We conducted a feasibility study to test the tool’s effectiveness in a large-scale DBS study, where subjects received a home-monitoring kit consisting of an iPhone and Apple Watch, pre-configured with the RM app to enable remote data collection. Compliance in this paper is defined as adherence to the RM app and Apple watch usage. Analysis of 67 subjects from the study demonstrated an average compliance rate of 63.3% for daily check-ins, 85.5% for monthly surveys and 61.9% for passive data with an average of 55 days of post-implant data. The study highlights the feasibility of frequent monitoring in the early post-implant period that could lead to optimal outcomes for patients. The platform developed can further optimize study execution and be extended to other chronic conditions treated with neuromodulation implants such as depression and pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s Disease (PD), a common neurodegenerative disease, affects about 10 million people worldwide1. Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS), which involves the implantation of electrodes in specific areas of the brain to modulate neural activity and alleviate symptoms, is an established neuromodulation treatment for PD and other movement disorders, such as Essential Tremor (ET). DBS offers patients with neurodegenerative diseases flexible and customizable therapy intended to improve quality of life. However, DBS therapy requires multiple programming appointments and complex assessments, which can be burdensome for patients and their families.

Among the gaps facing the field of neuromodulation therapy are: (1) burden of therapy maintenance, (2) therapy access, and (3) discrete assessments in controlled environments2,3. To address these challenges, digital health tools have emerged as a promising solution for optimizing DBS therapy. Digital health is a rapidly evolving field that is transforming healthcare delivery. Access to ongoing care from DBS specialists can be cumbersome as it may require patients to take time off from work, commute long distances, arrange for travel, or work around a caregiver’s schedule. Conventional DBS therapy maintenance restricts patient independence as it is not optimized to patient goals or patient-clinician interactions. The challenges of patient independence and care access burden are further exacerbated due to limited specialists, racial and socioeconomic disparities, and an overall lack of consensus on DBS referral and timing4,5. While there was accelerated adoption of remote care during the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce risk of in-person visits for patients suffering from neurodegenerative conditions, it also highlighted the benefits of telemedicine that continue to be relevant. Specifically, digital solutions can mitigate existing barriers to care access and offer a cost-effective alternative to traditional care. Additionally, discrete assessments, often conducted in controlled clinical settings, offer an inaccurate snapshot of the patient’s condition.

Integration of digital health solutions with neuromodulation care has the potential to significantly improve patient outcomes and experience. Tools, such as wearable technology and mobile health platforms, may offer personalized and efficient solutions for accessing patient care, improving clinical assessments, and enhancing neuromodulation therapy while limiting patient travel, time, and cost6,7,8. Additionally, by collecting and analyzing large amounts of data from patients undergoing DBS, scientists and healthcare providers can gain insights into how DBS works and develop more effective therapies9. Routine integration of digital platforms and large-scale data infrastructure can provide healthcare providers and translational scientists with low-burden remote monitoring capabilities, allowing for real-time virtual programming and optimization of patients’ therapy.

The foundation for an optimized digital health platform, that combines clinical assessment and neuromodulation therapy delivery, was set with the recent introduction of the NeuroSphere(TM) Virtual Clinic platform. Virtual Clinic enables remote neurostimulation programming and telehealth services directly from the patient’s or clinician’s therapy controller app. In addition to modifying programs remotely, its key features include secure in-app audio/video conferencing, an encrypted backend (cloud-based server enabling communication between clinician and patient devices), the ability to remotely interrogate the system, and the protected recovery program (PRP) capability, a safety feature that allows the user to define a default program in the event of a network interruption10.

A digital health platform that can extend these initial capabilities with integrated remote monitoring is critical for optimizing DBS therapy. Remote monitoring enables healthcare providers to remotely monitor patients’ health status including vital signs, using digital tools such as wearable devices, sensors, and mobile apps. In the context of neuromodulation therapy, it will need to facilitate access to real-time clinical outcomes, including symptom severity and side-effects, for health care providers and empower patients by providing them with a better understanding of their progress. In addition, these technologies should help identify digital biomarkers critical for understanding the onset, symptoms, medication-related fluctuations and side-effects, and correlation to DBS treatment2,11.

Digital biomarkers for cardinal motor symptoms of PD (ex: tremor and bradykinesia) have been quantified in recent studies using non-invasive sensors that include inertial measuring unit (IMU) sensors, such as, accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers12,13. The results from these studies demonstrate that signals from wearable devices integrated with IMU sensors correlate with clinical assessment of PD motor symptoms and provide a promising avenue for automating assessments and reducing dependency on in-person clinical evaluation14,15,16. Additionally, increased acceptability of body-worn sensors by patients makes them a practical option for remote monitoring of ongoing therapeutic optimization17,18.

Through our investigational remote monitoring application (RM App) integrating patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and objective data using wearables, we aimed to develop an accessible, data-driven digital tool to remotely monitor patient symptoms and deliver low-burden and easy-to-access individualized DBS therapy.

Results

Sixty-seven subjects (n = 67), who received a home-monitoring kit in the feasibility study, were evaluated for compliance analysis. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the cohort included in our feasibility analysis. For all subjects, the mean duration for passive data collection was 6.8 days during the baseline period and 55 days for the post-implant period. Compliance in this paper is defined as adherence to the RM app and Apple watch(R) usage. During the remote monitoring phase, subjects complied with IMU data collection for an average of 22.6 days; this required active start on the watch for high-fidelity signals. Compliance rate was defined as the number of times a survey was completed divided by the number of times it was administered. For example, for a subject enrolled in the remote monitoring phase for 100 days, completion of 70 daily check-ins would imply 70% compliance rate. In the context of PDQ-39, the threshold for compliance was referenced to 3 survey administrations. We observed an average compliance rate of 61.2% for daily check-ins (PGIS) and 83.6% for monthly surveys (PDQ-39) (Fig. 1).

A group analysis of all subjects demonstrated that on average, subjects wore their watch 61.9% of the time with an average of 55 days of post-implant data. Forty-three out of 67 subjects had over 50% compliance with completion of daily check-ins and passive data collection. HealthKit data collected from the watch included activity metrics (step count, stride length, active minutes, etc.) and physiological measures (heart rate, heart rate variability, SpO2, etc.), while core-motion and IMU data included high-resolution accelerometer and gyroscope signals. On average, patients improved on the PGIS over the course of 3 months. At baseline, mean PGIS score was 4.4 ± 0.65, at 1-month it was 3.6 ± 0.09 and at 3-months it was 3.2 ± 0.08. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) for PGIS post-implant was compared to the baseline period and determined according to the paired Wilcoxon test with a one-sided alternative hypothesis on median values (Fig. 2).

Daily check-in scores (PGIS) tracked from baseline to 3 months post implant. On average, patients improved on the PGIS over the course of 3 months. At baseline, mean PGIS score was 4.4 ± 0.65, at 1-month it was 3.6 ± 0.09 and at 3-months it was 3.2 ± 0.08. Statistical significance (p < 0.05*) of PGIS post-implant compared to the baseline period was determined according to the paired Wilcoxon test with a one-sided alternative hypothesis on median values; multiple comparisons correction was applied.

Discussion

Here, we summarized the development of a remote monitoring platform that enables us to collect PROs and objective data via consumer-grade wearables in a customizable fashion. We tested this platform for usability and feasibility in a large-scale clinical study focused on remote DBS programming for PD (NCT05269862). The remote monitoring platform, currently available on iOS, was developed to integrate passive and objective data to support patient-feedback and clinical decision-making. Results from the study demonstrate that the platform has potential for real-world adoption.

Continuous, real-world data are essential for optimizing neuromodulation therapy; technological progress in neuromodulation has thus far depended on hardware-based improvements such as implantable device miniaturization and improved geometry of electrodes. However, currently, there is a need for digital solutions that can extend care beyond the clinic to address increasing care-access burden and to evaluate patient concerns in real-world scenarios. Advancements in wearable sensors, algorithm development and the Internet of Things (IoT) platform have enabled development of remote monitoring systems for movement disorders2,19,20,21. Wearable sensors, such as smart watches embedded with accelerometers and gyroscopes, can capture disease traits, including gait patterns22,23, tremor episodes, and activity levels; these sensors connect to the internet through data aggregators and transform signals into clinically relevant knowledge.

One example of a remote monitoring platform for movement disorders is the “MyParkinsoncoach” system, which demonstrated efficiency in the comprehensive management of PD. This platform used a combination of wearables and smartphone technology to collect patient data and provide personalized feedback24. Another platform, the iHandU system25, measures bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor to track PD. Other similar systems have also been developed for epilepsy management26.

We built the RM app to combine passive monitoring through consumer-grade wearables and disease-specific patient reported outcomes (PROs) to leverage ubiquitous platforms such as Apple Watch, Fitbit, and Oura ring. Objective data collected through this system includes validated algorithms27, and high-resolution data to bridge the gap where classifications are not yet defined. Collecting data passively and creating a low-burden experience improves compliance, which is essential for collecting patient-centric data to build a more holistic profile for the patient and improve clinical decisions. To note, in the RM app iteration presented as part of the feasibility study, patients received pre-configured iPhones and Apple Watches to better streamline data collection. Though the RM app is compatible with Fitbit and Oura, those wearables were not used in the study. The vision for the platform is to be wearable-agnostic and customizable in the future. In subsequent iterations, the RM app may be downloaded from the marketplace (ex: Apple app store) and patients could configure the devices with the help of their clinician tailored to specific needs. For example, if the platform is leveraged for a study-specific use, the clinician may provide study-specific identifiers to enable the correct version. Alternatively, if the app-use is for clinical decision-making, prescriptive identifier may be applied that may activate features with a finite timeline and provide options for reminders, etc. The flexible infrastructure would allow for customizations as required. Objective data can also help identify kinematic biomarkers. Though the DBS app is currently separate from the RM app, intermittent learnings could help optimize clinical outcomes by providing more guidance for clinicians with data-driven personalized insights. Eventually, if the biomarkers are robust and detectable at the required time-resolutions, automated implementations could be explored. The frequency of PROs can provide important insights into the effectiveness of therapy for movement disorders. Hence, the RM app was built to integrate PROs at variable frequencies; PGIS was recorded daily to account for normal fluctuations, while qoL metrics and other surveys were delivered at a lower cadence (monthly or when clinically needed). Also, survey completion was coupled with data upload so a daily cadence for PGIS ensured fewer data gaps. PROs can be valuable in assessing treatment effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes in a variety of movement disorders, including PD, ET, and dystonia. A systematic review focused on PD highlighted the importance of selecting appropriate PROs for different measures and the need for consistent and frequent monitoring of patients to ensure optimal outcomes28. A study29 found that frequent PRO assessments may be valuable in identifying changes in non-motor symptoms, such as cognitive function and mood. The study found that patients’ PRO scores on these non-motor symptoms were highly variable and could change rapidly over time, highlighting the importance of frequent monitoring to ensure that these symptoms are effectively managed. In the feasibility study presented here, the PROs were determined based on the primary goals of the clinical study and pre-configured in the app. Future iterations may allow clinicians to choose which PROs they might be interested in based on research versus clinical needs.

In addition to PROs and wearables, remote monitoring systems for movement disorders should also include video and voice analytics, and other sensor-based technologies. These systems allow for real-time monitoring and can provide valuable insights into patient symptoms and behavior. Future iterations of the RM app will need to leverage artificial intelligence (AI) driven features to further optimize experience and clinical insights. Specifically, by analyzing real-time physiological data from body-worn sensors and implantable devices, AI algorithms can suggest optimized DBS settings to improve motor function and reduce side-effects30,31,32. These insights can be integrated into acute and longitudinal clinical decision-making, paving the way for adaptive and closed-loop systems. However, as data becomes increasingly informative, careful consideration of privacy and data security is necessary to ensure that patient data is protected and used responsibly33.

With these AI driven features, the proposed remote monitoring system, RM, can be extended to other chronic conditions treated with neuromodulation such as depression and pain. While depression is traditionally diagnosed through face-to-face or virtual encounters with a clinician, research into virtual technologies has revealed that computer applications can detect depression based on facial expressions and eye movements34,35. Additionally, a study investigating a text-messaging based social support intervention for chronic pain patients attending pain clinics in New York City demonstrated reduced scores on pain perception, reduced pain interference, and improved rating of affect over 4 weeks36. Research into video analytics and text-based digital health applications demonstrate the potential for these technologies to improve therapy for chronic illnesses in addition to movement disorders.

The remote monitoring of patients with chronic illness is efficient37 and cost-effective for healthcare utilization7,38,39 especially in patients with implanted devices40,41,42. Recent modifications in reimbursement policies are aligned with the use of remote monitoring; CPT codes around remote patient (RPM) and remote therapeutic (RTM) monitoring were first introduced in 2018. The latest guidelines around these codes are based on at least 50% compliance by patients (ex: 16 days of data transmitted within a 30-day period). Results from our clinical feasibility study support adherence to these guidelines, as we observed compliance above these thresholds from patients representing various geographies (US and Europe). A major limitation for patients to adhere to the required compliance is reliable internet access. Additionally, we observed that compliance decreased over time implying a general lack of motivation. For the feasibility study, patients did not receive specific insights about their data. However, future iterations could be aimed at further improving compliance by personalizing the app experience based on insights that are useful for patients to monitor their well-being; these features could include elements of gamification and clear instructions with finite requirements that provide short-terms goals to increase motivation.

Lastly, this platform is a technology for optimizing study execution. By leveraging decentralized monitoring, large-scale clinical studies can be designed to directly engage patients. Increased frequency of data collection, which is challenging with conventional research methods, allows for comprehensive evaluation of patients. The option of a low-cost, efficient method of research leads to high quality data leading to results with adequately powered studies. As we continue to develop this platform to leverage these features, resources will be expanded to include patient educational material and digestible feedback. We also plan to focus on customization of the user-interface specific to the patient accounting for their goals and specific symptoms.

In conclusion, the RM app is a remote monitoring platform that can help address the growing need for passive and objective data to support patient feedback and clinical decision-making for movement disorders. Its compatibility with several wearable systems, patient-centric data collection, and low-burden experience improves compliance, enabling improved patient profiles and clinical decisions. The use of IoT and wearable technologies in healthcare can further transform data into clinically relevant knowledge, benefiting the efforts of caregivers in delivering more efficient and comprehensive healthcare.

Methods

The RM app is an iOS-based remote monitoring application that integrates wearable data capture and PROs via surveys in a patient-centric manner. Patient preferences are integrated into the interface enabling a flexible platform that is designed for use in a decentralized setting, such that patients may have greater access to care, as services are provided in more convenient and accessible ways. The infrastructure is developed with a plug and play (PnP) vision. PnP refers to the ability of this platform to automatically detect and configure hardware when connected. The platform, as defined here, includes the RM app and the wearables; it is not currently interfacing with the app that enables adjustment of DBS parameter. In its current iteration, it is developed as a data collection tool. Specifically, it is designed to be compatible with several consumer-grade wearables and allows for passive data collection for a low-burden experience. Figure 3 illustrates the overarching vision of the Remote Therapeutic Monitoring Platform, where the backend can accept multimodal data as objective input from wearables (skin adhesives, smart ring, or smart watch) and patient-reported outcomes surveys, diaries, etc.). This data can be analyzed for specific insights using validated algorithms that are available through the backend. In the depicted example, we are showing how insights about severity and presence of cardinal symptoms for PD can be extracted using this framework. Note, additional data is required to develop validated algorithms for the symptoms described. Development of this platform is an effort to further streamline collection of the necessary data (Fig. 3).

Conceptual framework of the Integrated platform for the RM app leveraging the cybersecurity infrastructure from commercially available Neurosphere platform with compatibility to consumer-grade wearables and validated algorithms to determine presence and severity of symptoms. The goal of the platform is to improve patient experience and optimize neuromodulation therapy. This figure illustrates the overarching vision of the Remote Therapeutic Monitoring Platform, where the backend can accept multimodal data as objective input from wearables (skin adhesives, smart ring, or smart watch) and patient-reported outcomes surveys, diaries, etc.). This data (raw traces) can be analyzed for specific insights using validated algorithms that are available through the backend. In this example, we are showing how insights about severity and presence of cardinal symptoms for PD can be extracted using this framework.

Back end

The RM app backend is generalized to support multiple implementations of the app. In terms of cyber-security, the cloud infrastructure is built on the commercial NeuroSphere platform and leverages best-in-class protection ensuring patient data privacy and state-of-the-art mechanisms to authenticate and establish a secure session.

The cloud services are hosted on an ISO 27001 certified infrastructure43. All data within the platform (cloud system, devices, and mobile app) are encrypted in transit and at rest. The communication channels for this data transfer are protected using TLS1.244. The data ingestion to the cloud is protected by Web Application Firewall (WAF) policies that intercept and inspect every request for any known attacks45. The cloud resources’ access points are controlled at a granular level and protected at a network level to isolate them from open internet access. The infrastructure further uses certificate pinning technique to avoid Man-In-The-Middle (MITM) attacks46.

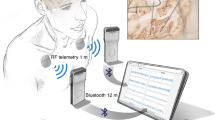

Lastly, the backend is designed to be configurable enabling dynamic application updates with minimal interruption to users. The mobile app establishes a certificate-based authentication with the cloud services to upload data collected without additional user intervention for repeated login to the app. Data from sensors are uploaded via (1) device-to-cloud transfer (ex: Apple Watch) or (2) cloud-to-cloud transfer (ex: Fitbit or Oura). The approach is contingent on options available by the wearable manufacturer. For the current iteration, the platform leverages an SDK to interface with Apple devices and API to connect to Fitbit or Oura. Data permissions for specific metrics are obtained during configuration.

User Interface (UI)

As noted, the app was designed to deliver a personalized experience (Fig. 4). Hence, it was essential for the UI to be customizable in a study-specific manner. Patients respond to clinically validated surveys and connect to specific wearables based on study requirements. Features, such as, language, resources, data-feedback, etc. can be enabled, disabled, or modified to match patient requirements. Sensor data packets are uploaded periodically to the secure backend via automated queries. Also, when a survey is completed, any PRO data along with sensor data is uploaded; this is an additional, fail-safe mechanism with minimum user-burden for data upload in case periodic queries are interrupted.

Easy-to-navigate user interface of the RM application. The interface includes (1) Daily check-in using validated surveys (Patient Global Impression of Severity (PGIS)), (2) Timed surveys including validated quality of life metrics (Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire 39 (PDQ-39)) and (Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC), (3) Continuous objective sensor data collected through ubiquitous wearables (Apple Watch).

On the study monitoring side, the clinician has access to the app or web-portal to enter therapy-related information. For the feasibility study described below, survey questions for the study were determined based on the protocol. To improve compliance, surveys are delivered in synchrony with relevant clinical events (ex: programming sessions); Associated notifications are also time specific. An additional dashboard is available to the research team to monitor survey completion and wearable usage, and to visualize real-time data analytics (Fig. 5).

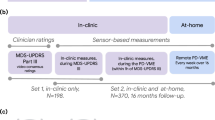

Feasibility study

We tested the feasibility of this investigational tool by implementing it in a large-scale DBS study (NCT05269862). This was a multi-site randomized control study with ethics approval from the central institutional review board (IRB), WCG IRB. When necessary, approval from additional site-specific IRBs in the US or independent ethics committees (EC) in Europe were obtained. All research in this study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Subjects with PD, who were candidates for DBS, provided written informed consent to enroll in the study. The primary goal of this study is to compare clinical outcomes in a cohort that has access to clinical intervention in-clinic and through the NeuroSphere Virtual Clinic platform versus one that is constrained to in-clinic visits. Both cohorts received a home-monitoring kit consisting of an iPhone and Apple watch, pre-configured with the RM app to enable remote data collection. For this study, we implemented a daily check-in survey based on the validated Patient Global Impression of Severity (PGIS). Additionally, monthly quality of life (qoL) measure, Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39) and 3-month teleprogramming survey are included referenced to the patient’s initial programming session. Lastly, a symptom improvement survey is captured by collecting PGIS and PGIC after a titration programming session, where iterative therapy adjustments are made. Through the apple ecosystem, we collect activity metrics from HealthKit, high-resolution IMU data from watch (accelerometer and gyroscope), and core motion data to determine tremor and dyskinesia metrics. The watch interface is designed to be a single-tap engagement to account for a population that is specifically suffering from a movement disorder. Additional details about the study will be presented in a separate publication focused on the results of primary endpoints.

Statistical analysis

The SciPy python package was used for all statistical analysis (SciPy Software, scipy.org). Statistical significance was determined according to the paired Wilcoxon test with a one-sided alternative hypothesis on median values; multiple comparisons correction was applied. The format for boxplots shown in this manuscript consists of the median as a center line surrounded by a box indicating the 25th and 75th percentiles. Whiskers indicate the outer-most datapoint that is not considered to be an outlier, where outliers are datapoints that are more than a distance of 1.5 times the inter-quartile range from the nearest quartile. Outliers are indicated as single datapoints.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is not publicly available to protect patient privacy. However, data relevant to the study will be made available in a de-identified format upon reasonable request to Abbott (yagna.pathak@abbott.com).

Code availability

The code generated for the current study is not publicly available to protect patient privacy. However, code sections relevant to the study will be made available in a de-identified format upon reasonable request to Abbott (yagna.pathak@abbott.com).

References

Simon, D. K., Tanner, C. M. & Brundin, P. Parkinson disease epidemiology, pathology, genetics, and pathophysiology. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 36, 1–12 (2020).

Pathak, Y. J. et al. Digital health integration with neuromodulation therapies: the future of patient-centric innovation in neuromodulation. Front. Digital Health 2021, 43 (2021).

Rammo, R., Gostkowski, M., Rasmussen, P. A., Nagel, S. & Machado, A. The need for digital health solutions in deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease in the time of COVID-19 and beyond. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 24, 331–336 (2021).

Cramer, S. W. et al. Persistent racial disparities in deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 92, 246–254 (2022).

Cabrera, L. Y. et al. Attitudes toward use and timing of deep brain stimulation: a patient’s with DBS perspective. Clin. Neurol. Neurosur 203, 106553 (2021).

Deer, T. R. et al. Teleprogramming service provides safe and remote stimulation options for patients with DRG-S and SCS implants. J. Pain Res. 2021, 3259–3265 (2021).

Heldman, D. A. et al. Telehealth management of Parkinson’s disease using wearable sensors: an exploratory study. Digital Bbiomark. 1, 43–51 (2017).

Lee, J. M., Woon, R., Ramsum, M., Halperin, D. S. & Jain, R. User engagement and assessment of treatment effectiveness in patients using a novel digital mhealth app during spinal cord stimulation screening trials. JMIR Hum. Factors 9, e35134 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. The role of large-scale data infrastructure in developing next-generation deep brain stimulation therapies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15, 717401 (2021).

Silburn, P. et al. Rapid development of an integrated remote programming platform for neuromodulation systems through the biodesign process. Sci. Rep. 12, 2269 (2022).

Pulliam, C. L. et al. Continuous assessment of levodopa response in Parkinson’s disease using wearable motion sensors. IEEE Trans Bio-med. Eng. 65, 159–164 (2017).

Torres, R. et al. Sensors for Parkinson’s disease evaluation. In 2017 International Caribbean Conference on Devices, Circuits and Systems (ICCDCS) 121–124 (IEEE, 2017).

van den Noort, J. C. et al. Quantification of hand motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: A proof-of-principle study using inertial and force sensors. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 2423–2436 (2017).

Rigas, G. et al. Assessment of tremor activity in the Parkinson’s disease using a set of wearable sensors. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 16, 478–487 (2012).

Rovini, E., Maremmani, C. & Cavallo, F. How wearable sensors can support Parkinson’s disease diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review. Front. Neurosci.-Switz. 11, 555 (2017).

Giuffrida, J. P., Riley, D. E., Maddux, B. N. & Heldman, D. A. Clinically deployable Kinesia™ technology for automated tremor assessment. Mov. Disord. 24, 723–730 (2009).

Fisher, J. M., Hammerla, N. Y., Rochester, L., Andras, P. & Walker, R. W. Body-worn sensors in Parkinson’s disease: evaluating their acceptability to patients. Telemed. e-Health 22, 63–69 (2016).

Pasluosta, C., Gassner, H., Winkler, J., Klucken, J. & Eskofier, B. An Emerging era in the management of parkinson’s disease: wearable technologies and the internet of things. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 19(16), 1873–1881 (2015).

Prince, J. & De Vos, M. A deep learning framework for the remote detection of Parkinson’s disease using smart-phone sensor data. in 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) 3144–3147 (IEEE, 2018).

Kostikis, N., Hristu-Varsakelis, D., Arnaoutoglou, M. & Kotsavasiloglou, C. An IoT-aware architecture for Parkinson’s disease remote monitoring using wearables. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 76, 98–110 (2017).

Mughal, H., Javed, A. R., Rizwan, M., Almadhor, A. S. & Kryvinska, N. Parkinson’s disease management via wearable sensors: a systematic review. IEEE Access 10, 35219–35237 (2022).

Moore, S., Yungher, D., Morris, T. et al. Autonomous identification of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease from lower-body segmental accelerometry. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 10, 19 (2013).

Capecci, M., Pepa, L., Verdini, F. & Ceravolo, M. A smartphone-based architecture to detect and quantify freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture. 50, 28–33 (2016).

Wijers, A., Hochstenbach, L. & Tissingh, G. Telemonitoring via questionnaires reduces outpatient healthcare consumption in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 8, 1075–1082 (2021).

Lopes, E. et al. iHandU: a novel quantitative Wrist rigidity evaluation device for deep brain stimulation surgery. Sens.(Basel). 20(22), 331 (2020).

Fortini, S., Espeche, A. & Caraballo, R. Telemedicine and epilepsy: a patient satisfaction survey of a pediatric remote care program. Epilepsy Res. 165, 106370 (2020).

Powers, R. et al. Smartwatch inertial sensors continuously monitor real-world motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med 13, eabd7865 (2021).

Martinez-Martin, P. What is quality of life and how do we measure it? Relevance to Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. Mov. Disord. 32, 382–392 (2016).

Martinez-Martin, P., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Kurtis, M.M., Chaudhuri, K.R. & Group, N.V. The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 26, 399–406 (2011).

Pastorino, M., Arredondo, M.T., Cancela, J. & Guillen, S. Wearable sensor network for health monitoring: the case of Parkinson disease. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. (2013).

Di Zubiena, F. C. G. et al. Machine learning and wearable sensors for the early detection of Balance disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Sensors 22, 9903 (2022).

Channa, A., Popescu, N. & Ciobanu, V. Wearable solutions for patients with Parkinson’s disease and neurocognitive disorder: a systematic review. Sensors 20, 2713 (2020).

Scott, I. A. Demystifying machine learning: a primer for physicians. Internal Med. J. 51, 1388–1400 (2021).

Wang, Q., Yang, H. & Yu, Y. Facial expression video analysis for depression detection in Chinese patients. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 57, 228–233 (2018).

Alghowinem, S., Goecke, R., Wagner, M., Parkerx, G. & Breakspear, M. Head pose and movement analysis as an indicator of depression. In 2013 Humaine Association Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction 283–288 (IEEE, 2013).

Guillory, J. et al. Piloting a text message-based social support intervention for patients with chronic pain: establishing feasibility and preliminary efficacy. Clin. J. Pain 31, 548 (2015).

Chew, D. S. et al. Clinical and economic outcomes associated with remote monitoring for cardiac implantable electronic devices: a population-based analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 38, 736–744 (2022).

Calò, L. et al. Economic impact of remote monitoring on ordinary follow-up of implantable cardioverter defibrillators as compared with conventional in-hospital visits. A single-center prospective and randomized study. J. Interv. Card Electr. 37, 69–78 (2013).

Bovbjerg, M. L., Lee, J., Wolff, R., Bangs, B. & May, M. A. Pilot study for managing complex chronic care medicaid patients with diabetes using a mobile health application achieves “Triple Aim” improvement in a primary care setting. Clin. Diabetes 35, 227–231 (2017).

Buchta, P. et al. The impact of remote monitoring of implanted cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) and cardiac resynchronisation therapy device (CRT-D) patients on healthcare costs in the Silesian population: three-year follow-up. Kardiologia Polska (Polish Heart J.) 75, 573–580 (2017).

Guedon-Moreau, L. et al. Costs of remote monitoring vs. ambulatory follow-ups of implanted cardioverter defibrillators in the randomized ECOST study. Europace 16, 1181–1188 (2014).

Lopez-Villegas, A., Catalan-Matamoros, D., Robles-Musso, E., Bautista-Mesa, R. & Peiro, S. Cost-utility analysis on telemonitoring of users with pacemakers: the PONIENTE study. J. Telemed. Telecare 25(24), 204–212 (2019).

ISO/IEC 27001 and related standards (2023, accessed 17 Mar 2023). https://www.iso.org/isoiec-27001-information-security.html.

Guidelines for the Selection, Configuration, and Use of Transport Layer Security (TLS) Implementations: NIST SP 800–52 Rev. 2. (2019, accessed 17 Mar 2023). https://csrc.nist.gov/News/2019/nist-publishes-sp-800-52-revision-2.

What is a Web Application Firewall (WAF)? (2023, accessed 17 Mar 2023). https://www.f5.com/glossary/web-application-firewall-waf.

Certificate and Public Key Pinning (2023, accessed 17 Mar 2023). https://owasp.org/www-community/controls/Certificate_and_Public_Key_Pinning.

Acknowledgements

We thank Binith Cheeran, MD, PhD, for support on study design and Aamna Ahsan for support on study execution. Additionally, we thank Allen Burton, MD, Douglas Lautner, PhD, and David Page, PhD, for their independent review of the manuscript. Lastly, we acknowledge Jagat Shah and his team for support in backend development and data monitoring.

Funding

Abbott labs funded this development and corresponding research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ST was the cloud architect of the system backend and developer of the smartphone application as well as technical design and implementation of the data storage and transmission protocols and contributed to the manuscript. WG assisted in the conception of the app design and user experience including the general concept of the application and the specific topics presented to patients and was involved in revising the manuscript. ER and TT led design and execution of the clinical feasibility study and contributed to the manuscript. AK led the data collection, analysis, and processing at the backend, and contributed to application design and the manuscript. BB contributed to implementation of the application and integration of core motion data. YP led manuscript writing, and application design, development, and testing; she contributed to the clinical feasibility study execution.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This development and corresponding research is funded by Abbott. Author WG is a consultant for Abbott, BehavVR, Fundamental VR, HOAG, Neo Auvra, Penumbra. Authors ST, TT, AK, BB, ER and YP were Abbott employees when this work was completed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thankathuraipandian, S., Greenleaf, W., Kyani, A. et al. Development of a remote therapeutic monitoring platform: applications for movement disorders. Sci Rep 14, 29837 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80567-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80567-z