Abstract

The glymphatic system of fluid flow through brain tissue may clear amyloid-β during sleep and as such underlie the need for sleep. Dysfunctional glymphatic transport has been implicated in pathological conditions ranging from stroke and dementia to psychiatric illnesses. To date, the fastest observed in-vivo brain flows have been reported after the manipulation of blood osmotic pressures. Surprisingly, the brain seems to shrink while receiving more influx. Though influx of an incompressible fluid might expand the tissue, no physical theory for these observations has been proposed. We here present a minimal mathematical model of brain pressure, deformation, and fluid flows due to vascular osmotic pressures. The model is based on Darcy flow, linear poroelasticity theory and conservation of mass. We propose that a screened Poisson equation holds for interstitial pressure because vascular filtration corresponds to fluid divergence. The model resolves the apparent paradox of combined fluid influx with tissue shrinkage by showing that fluid absorption into the blood can drive both. In this model, small glucose concentration differences between plasma and brain can drive brain flow velocities observed in recent in-vivo assays. Osmosis may therefore drive brain fluid flow under physiological conditions and provide an explanation for the known correlations between diabetes and dementia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the glymphatic theory, bulk flow of fluid through the brain parenchyma flushes solutes out and may prevent dementia by clearing disease-related proteins1. It has been proposed that glymphatic clearance underlies the biological need for sleep since wakefulness potently suppresses brain fluid transport2. Due to the clinical significance, many candidates for fluid flow driving forces have been investigated including arterial pulsations, slow wave neural activity, breathing, and pressures related to fluid production3,4,5,6,7.

Two recent experimental reports raised the blood osmolyte concentration by 50 mOsm and found faster fluid flows and brain deformation8,9. Plog, Mestre et al. reported that in-vivo cerebrospinal fluid tracers flow faster by roughly 3 mm/h on the brain surface and accumulate faster in the brain after stimulation with either mannitol (a plant sugar confined to the blood) or hypertonic saline8. Lilius, Rosenholm et al. reported in-vivo magnetic resonance imaging of brains shrinking by roughly 4% after injection of hypertonic saline to the blood (Fig. 1a)9. These reports demonstrate faster inflow of incompressible fluid to the brain along with brain shrinkage but propose no theory to reconcile this apparent paradox.

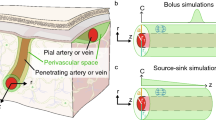

Schematic of the model domain consisting of a deformable porous tissue (soft yellow) with uniform vasculature. (a) Coronal MRI from reference9 in which the ventricles are enlarged due to 50 mOsm hypertonic stimulation of the blood (lower panel) compared to baseline ketamine/xylazine anesthesia (upper panel, reprinted with permission). (b) A coronal section of the mouse brain is simplified as a slice of a symmetrical tissue sphere (c) with an inner sphere representing the ventricles. (d, e) Our model considers the brain to be uniform (d) by averaging out volumes with arterioles, capillaries, and venules (e). (f) To get a rough intuition for why divergence should equal absorption, consider the one-dimensional example: If interstitial fluid enters a small cube (magnified red box from e) with side-lengths \(\Delta x\) at velocity \({v}_{1}\) and exits with velocity reduced to \({v}_{2}={v}_{1}-q\Delta x\) due to capillary absorption, then the divergence of the fluid velocity is \(\nabla \cdot {\varvec{v}}=\left({v}_{1}-{v}_{2}\right)/\Delta x=-q\). We use this proposition along with standard osmotic membrane flow and the Darcy law for porous fluid flow to find a screened Poisson equation for the interstitial fluid pressure (Eq. 3).

A concentration difference of 50 mOsm is far from physiological conditions but can occur during e.g. osmotherapy. Under physiological conditions such as rest, blood sugar concentrations can be greater than brain interstitial concentrations by ~ 4 mOsm10,11,12. According to van ’t Hoff’s law of osmotic pressure13 this is sufficient to generate 72 mmHg of hydrostatic pressure, which is far higher than other candidate drivers.

Linninger and co-workers have proposed that physiological osmotic pressures can drive interstitial fluid flow in the brain, as suggested in the well-known Starling principle14. These authors use elaborate hydraulic network models to successfully explain transient variations in cerebrospinal fluid pressure following osmotic treatments14,15. But the pressure–volume relationship used by Linninger et al. is empirical rather than derived from elasticity theory and the model is numerical rather than analytical.

Tully and Ventikos developed a multiple poroelastic network model representing separately pressures in arteries, capillaries, veins, extracellular spaces, ventricles, and subarachnoid spaces along with flow within and between each, in order to model evolving ventricle displacement in hydrocephalus16. The model can be solved numerically to show that increased blood brain barrier permeability and compliance of arteries and capillaries can cause hydrocephalus essentially by transmitting arterial pressure to the cerebrospinal fluid.

We here seek an analytically tractable minimal continuum model of stationary brain interstitial pressure, fluid flow, and deformation due to osmosis (Fig. 1b-f). The continuum consists of cells, extracellular pore spaces and blood brain barrier on arterioles, capillaries, and venules (Fig. 1e). We base our model on the Darcy law of fluid flow in porous media, linear poroelasticity theory, and conservation of mass.

The modelled brain under increased blood osmotic pressure

The model domain is described in terms of extracellular pressure \(p\), fluid flow velocity \({\varvec{v}}\), and displacement \({\varvec{u}}\), all as functions of blood osmotic imbalance \(\Psi\) (see Supplementary Information for details). We define \(\Psi\) as \(\Psi ={p}_{\text{blood}}-\Pi\), where \({p}_{\text{blood}}\) is the average blood pressure, and \(\Pi\) is the osmotic pressure on the blood brain barrier given in the van ‘t Hoff approximation for dilute solutions as \(\Pi =RT\Delta c\), (with \(\Delta c\) the osmolyte concentration difference, \(R\) the gas constant and \(T\) the temperature)13. We take \(\Psi\) to be constant for simplicity. We measure pressure relative to cerebrospinal fluid pressure in ventricles and subarachnoid spaces and take these to be equal.

The production or filtration \(q\) across the blood brain-barrier (a volume flow rate per unit tissue volume) can be calculated from the osmotic pressure imbalance using the classic Kedem-Katchalsky equations for perfect semi-permeable membranes17, \(q=L\left(p-\Psi \right).\) Here, \(L=\widetilde{{A}_{b}}{L}_{p}\) where \(\widetilde{{A}_{b}}\) is the relative blood brain-area (with dimension area over volume i.e. inverse length) and \({L}_{p}\) its hydraulic permeability (with dimension length over time over pressure). This flux corresponds to the divergence of interstitial fluid velocity \({\varvec{v}}\) (a flux per area, see Fig. 1f),

The standard Darcy law for porous fluid flow relates interstitial flow to the pressure gradient as

Taking the divergence of both sides of1, assuming constant \(\eta\) and \(\kappa\), results in a screened Poisson equation for the pressure imbalance (see Supplementary Information for a derivation including the effect of varying \(\kappa\)).

Here, \({\nabla }^{2}\) is the Laplace operator and \({\gamma }^{2}=\widetilde{{A}_{b}}{L}_{p}\eta /\kappa\) which includes the fluid viscosity \(\eta\) (with dimension pressure times time) and the intrinsic permeability of the extracellular pore space \(\kappa\) (with dimension area). This intrinsic permeability is roughly proportional to the cross-sectional area of the space between cells and is distinct from the hydraulic permeability of the blood brain barrier \({L}_{p}\). The screening length \({\gamma }^{-1}\) has units of length and gives a characteristic distance for the pressure variation. We estimate this length at roughly 8 mm (see Supplementary Information).

The resulting fluid pressure causes brain displacement, which we describe using standard poroelastic theory, e.g. Biot consolidation theory18. Specifically we use Biot’s modified Hooke’s law along with the conditions for incompressibility and mechanical equilibrium to get the modified Navier-Cauchy equation (see Supplementary Information)19.

Here, \(\mu\) and \(\lambda\) are the Lamé elastic moduli and \({\varvec{u}}\) is the displacement vector field. This corresponds to including the fluid pressure gradient as an “external” body force.

These equations for pressure, velocity, and displacement may in principle be solved in any brain geometry. For our minimal model, we use a sphere with rotational symmetry (see Fig. 1b-f). The solutions of3 are then linear combinations of \(\frac{1}{r}{e}^{\pm\upgamma r}\) and4 can be solved analytically. As boundary conditions, we take the inner ventricular surface to be mechanically free and the outer pial surface to be fixed. Solutions are given in Supplementary Information.

The model requires the four flow-related parameters here combined as \({\gamma }^{2}\), two elasticity parameters, and the osmotic imbalance \(\Psi\). While \(\Psi\) is reliably established and confirmed in independent protocols by references8,9, a wide range of material parameters can be found in the literature. We find a \(\gamma\) directly from the most applicable literature (see Supplementary Information, Table 1) and present our results with an interval consisting of a factor 2 uncertainty on brain stiffness and factor 50% on the screening length \(\gamma\).

Experimental reports match the model predictions

The model predictions on pressure, fluid velocity, and displacement fields due to 50 mOsm stimulation are shown and compared with references8,9 in Fig. 2. Despite the large osmotic pressure imbalance (corresponding to 900 mmHg), we find the intracranial pressure to vary by less than 4 mmHg from surface to mid-tissue due to the large inflow (Fig. 2a). The radial fluid velocity points into the tissue with speeds of ~ 2 mm/h at the surfaces (Fig. 2b). Reference8 reports tangential surface velocity of ~ 3 mm/h rather than radial velocity, but the surface flow likely penetrates eventually and should according to models of this flow be similar20. The pressure profile is nearly parabolic with a minimum near the center of the tissue (Fig. 2c). The tissue is compressed by 2.6% and the ventricles correspondingly enlarged (Fig. 2c-e). The 4% compression in reference9 is therefore well within the prediction range.

The model predicts pressures, fluid velocities, and deformations due to 50 mOsm blood stimulation which match experimental reports. (a) The pressure field which obeys our Eq. 3 (on same first axis as c). (b) The radial velocity of interstitial fluid through the tissue as a function of radius (on same first axis as c). The tangential velocity was measured at 3 mm/h by reference8. (c) The displacement \({u}_{r}\) as a function of radius shows the ventricular side pushed outwards by ~ 0.1 mm. (d) A coronal section matching Fig. 1d in which green lines are undeformed while orange lines are corresponding displaced points and black arrows indicate flow velocity. (e, f) Brain compression and fluid velocity at the subarachnoid surface as functions of osmolyte concentration imbalances between blood and interstitial spaces. Reference8,9 measured compression of ~ 4% and a tangential velocity of 3 mm/h at \(\Delta c\approx 50\) mOsm. Credibility intervals represent an interval consisting of a factor 2 uncertainty on brain stiffness and factor 50% on the screening length \(\gamma\).

The model additionally predicts the total absorption, which we compare with baseline cerebrospinal fluid production rates (see Supplementary Information). These have been estimated at ~ 100 nl/min without osmotic stimulation21, whereas the modelled 50 mOsm results in a total absorption rate of ~ 1460 nl/min. We find it plausible that the 50 mOsm osmotic stimulation could explain this factor 15 difference.

Physiological blood glucose concentrations are sufficient for glymphatic flow

As mentioned, plasma glucose is reported to be ~ 4 mOsm lower in brain than in plasma during physiological rest in rats and humans10,11,12. According to the model presented here, this 4 mOsm concentration difference causes fluid flow into the brain with a surface velocity around 0.1 mm/h (Fig. 2f inset). Thus, even osmolyte concentration differences during sleep may be sufficient to drive fluid flow through brain tissue.

Net filtration drives bulk efflux from tissue

We next asked how pressure and flow respond to hypotonic rather than hypertonic blood. When blood is hypotonic by 4 mM, the central tissue pressure is raised by less than 0.2 mmHg and a bulk fluid velocity of up to 0.1 mm/h is reached with minor deformation (Fig S1a-d). A recent assay based on in-vivo magnetic resonance imaging of interstitial tracers estimated outwards flow velocities during ketamine/xylazine anesthesia of roughly 0.1 mm/h 22. In this case, net filtration of plasma drives fluid out of the tissue towards cerebrospinal fluid compartments which is likely more effective for waste clearance.

Discussion

As presented above, a minimal model of osmotic pressures, fluid flows, and brain deformation resolves theoretical issues in experimental osmotic studies while matching their data. The model predicts that physiological oscillations in blood osmolytes, such as sugar, should drive fluid flows with velocities matching those recently reported in an in-vivo assay of the glymphatic system. The ongoing search for drivers of brain fluid flows during sleep should therefore be expanded to include osmosis.

The novelty of the present model is to stress the possibility that the interstitium not only conducts flow but modifies it by osmosis over the blood brain barrier. Other candidate drivers such as slow vasomotion5, functional hyperemia4, or arterial wall pulsations3 produce flow through the tissue without additional sources or sinks. Sources and sinks likely dominate the flow when the osmolyte concentration difference is large as in references8,9, but in general these mechanisms may have similar magnitudes. Pressure oscillations may require elastic cellular valves to drive directional flow23,24, and could interact with a poroelastic tissue in a time-dependent ways25. All of the drivers are sensitive to the permeability of the brain and therefore more likely to operate during sleep when the porosity of the brain is greatest2. Functional hyperemia and arterial wall pulsations may drive flow localized to specific brain regions, while the present mechanism generates more global flows.

Our model provides a mechanistic basis for statistical correlations between dysregulated blood osmolytes and dementia. A 25-year study of elderly humans reported that those with blood sodium concentrations elevated by ~ 4 mM compared to the average had a threefold higher prevalence of dementia26. Further, there is a higher incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in subjects with diabetes or increased fasting glucose which remain to be explained27. Similarly, a recent study on time-restricted feeding, which normalize blood sugar oscillations, reported improved clearance of amyloid plaques and reduced dementia28. With both hypernatremia and excessive glucose concentrations, the glymphatic clearance could be disrupted by reduced filtration of plasma into the brain, if our model is correct.

We have reduced the complex architecture of the brain to a homogenous and symmetrical sphere and naturally lost precision doing so. For example, periarterial spaces may increase fluid access to deep tissue, while restrictive surface membranes may reduce it22. Since our model does not resolve these and similar microscopic features, it also cannot resolve flow directions between periarteriolar and venous spaces. The model is further restricted to slowly varying quasi-steady states since no time-dependence is modelled. This is reasonable given that the typical time-scale for osmolyte concentrations and blood pressure is minutes8 whereas the time-scale for oscillations due to respiration and arterial pulsations is seconds. The assumed linear elasticity of the model fails for large deformations where also changes in permeability are likely to play a role29. Future work should also critically test if the proposed screened Poisson equation for pressure holds across averages of finely resolved vasculature with physiological oscillations in blood osmolytes. Finally, key parameters including blood brain barrier permeability and interstitial permeability are currently difficult to measure, but important determinants of flow and deformation.

Glucose and sodium are not the only osmolytes in blood and brain, so the 4 mOsm concentration differences cited here are probably compensated for by other osmolytes, such as lactate. However, as noted above, if the true osmolyte difference is smaller, even 1 mOsm, our model predicts fluid flows matching experimentally measured resting state velocities. Future work should determine steady state differences in total osmolytes, for example measuring osmolality of interstitial fluid and plasma sampled simultaneously.

In short, we here proposed physiological differences in blood osmolytes as a driver of brain fluid flows using a minimal mathematical model.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files including code with https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13808345.

References

Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow Through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 4(147):147ra111–147ra111 (2012).

Xie, L. et al. Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain. Science. 342(6156), 373–377 (2013).

Mestre, H. et al. Flow of cerebrospinal fluid is driven by arterial pulsations and is reduced in hypertension. Nat Commun. 9(1), 4878 (2018).

Holstein-Rønsbo, S. et al. Glymphatic influx and clearance are accelerated by neurovascular coupling. Nat Neurosci. 26(6), 1042–1053 (2023).

Fultz, N. E. et al. oupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science. 366(6465), 628–631 (2019).

Rasmussen, M. K., Mestre, H. & Nedergaard, M. Fluid transport in the brain. Physiological Reviews. 102(2), 1025–1151 (2022).

Jiang-Xie, L. F. et al. Neuronal dynamics direct cerebrospinal fluid perfusion and brain clearance. Nature. 627(8002), 157–164 (2024).

Plog BA, Mestre H, Olveda GE, Sweeney AM, Kenney HM, Cove A, et al. Transcranial optical imaging reveals a pathway for optimizing the delivery of immunotherapeutics to the brain. JCI Insight. 2018 18;3(20).

Lilius TO, Rosenholm M, Klinger L, Mortensen KN, Sigurdsson B, Mogensen FLH, et al. SPECT/CT imaging reveals CNS-wide modulation of glymphatic cerebrospinal fluid flow by systemic hypertonic saline. iScience. 2022;25(10):105250.

Gruetter, R., Ugurbil, K. & Seaquist, E. R. Steady-State Cerebral Glucose Concentrations and Transport in the Human Brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 70(1), 397–408 (1998).

Choi, I. Y., Lee, S. P., Kim, S. G. & Gruetter, R. In Vivo Measurements of Brain Glucose Transport Using the Reversible Michaelis-Menten Model and Simultaneous Measurements of Cerebral Blood Flow Changes during Hypoglycemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 21(6), 653–663 (2001).

Barros, L. F., Bittner, C. X., Loaiza, A. & Porras, O. H. A quantitative overview of glucose dynamics in the gliovascular unit. Glia. 55(12), 1222–1237 (2007).

Marbach, S. & Bocquet, L. Osmosis, from molecular insights to large-scale applications. Chem Soc Rev. 48(11), 3102–3144 (2019).

Linninger, A. A., Xu, C., Tangen, K. & Hartung, G. Starling forces drive intracranial water exchange during normal and pathological states. Croat Med J. 58(6), 384–394 (2017).

Buishas, J., Gould, I. G. & Linninger, A. A. A computational model of cerebrospinal fluid production and reabsorption driven by Starling forces. Croat Med J. 55(5), 481–497 (2014).

Tully, B. & Ventikos, Y. Cerebral water transport using multiple-network poroelastic theory: application to normal pressure hydrocephalus. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 667, 188–215 (2011).

Kedem, O. & Katchalsky, A. Thermodynamic analysis of the permeability of biological membranes to non-electrolytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1(27), 229–246 (1958).

Biot, M. A. General Theory of Three-Dimensional Consolidation. Journal of Applied Physics. 12(2), 155–164 (1941).

MacMinn, C. W., Dufresne, E. R. & Wettlaufer, J. S. Large Deformations of a Soft Porous Material. Phys Rev Applied. 5(4), 044020 (2016).

Tithof J, Boster KAS, Bork PAR, Nedergaard M, Thomas JH, Kelley DH. A network model of glymphatic flow under different experimentally-motivated parametric scenarios. iScience. 2022;25(5).

Liu, G., Ladrón-de-Guevara, A., Izhiman, Y., Nedergaard, M. & Du, T. Measurements of cerebrospinal fluid production: a review of the limitations and advantages of current methodologies. Fluids Barriers CNS. 19(1), 101 (2022).

Bork PA, Hauglund NL, Mori Y, Møllgård K, Hjorth PG, Nedergaard M. Modelling of brain efflux: Constraints of brain surfaces. PNAS. 2024;

Bork, P. A. R. et al. Astrocyte endfeet may theoretically act as valves to convert pressure oscillations to glymphatic flow. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 20(204), 20230050 (2023).

Gan, Y. et al. Perivascular pumping of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain with a valve mechanism. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 20(206), 20230288 (2023).

Fiori, M., Pramanik, S. & MacMinn, C. W. Flow and deformation due to periodic loading in a soft porous material. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 974, A2 (2023).

Allen MD, Springer DA, Burg MB, Boehm M, Dmitrieva NI. Suboptimal hydration remodels metabolism, promotes degenerative diseases, and shortens life. JCI Insight. 2019;4(17).

Arnold, S. E. et al. Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nat Rev Neurol. 14(3), 168–181 (2018).

Whittaker, D. S. et al. Circadian modulation by time-restricted feeding rescues brain pathology and improves memory in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Metabolism. 35(10), 1704-1721.e6 (2023).

McGuire, S., Zaharoff, D. & Yuan, F. Nonlinear Dependence of Hydraulic Conductivity on Tissue Deformation During Intratumoral Infusion. Ann Biomed Eng. 34(7), 1173–1181 (2006).

Bloomfield, I. G., Johnston, I. H. & Bilston, L. E. Effects of Proteins, Blood Cells and Glucose on the Viscosity of Cerebrospinal Fluid. Pediatric Neurosurgery. 28(5), 246–251 (1998).

Støverud, K. H., Darcis, M., Helmig, R. & Hassanizadeh, S. M. Modeling Concentration Distribution and Deformation During Convection-Enhanced Drug Delivery into Brain Tissue. Transp Porous Med. 92(1), 119–143 (2012).

Ge, G. R., Rolland, J. P., Song, W., Nedergaard, M. & Parker, K. J. Fluid compartments influence elastography of the aging mouse brain. Phys Med Biol. 68(9), 095004 (2023).

Ge, G. R., Song, W., Nedergaard, M., Rolland, J. P. & Parker, K. J. Theory of sleep/wake cycles affecting brain elastography. Phys Med Biol. 67(22), 225013 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Hajime Hirase and Felipe Barros for helpful comments, and Dan Xue for graphical illustrations.

Funding

This research was supported by Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation; National Institutes of Health (Grant no: R01AT012312); National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (Grant no: R01AT011439); NCCIH U19 (Grant no: NS128613); Simons Foundation; Career Award at the Scientific Interface from Burroughs Wellcome Fund; JPND; Independent Research Fund Denmark (Grant no: 3101-00282B).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PB made the model, PB and TB and analyzed the model, PB, TB, MG, EN, LH, and MN wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bork, P.A.R., Gianetto, M., Newbold, E. et al. Blood osmolytes such as sugar can drive brain fluid flows in a poroelastic model. Sci Rep 14, 29017 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80593-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80593-x