Abstract

We compared the visual performance and subjective outcomes of mini-monovision, crossed mini-monovision, and bilateral emmetropia using enhanced monofocal intraocular lenses (IOLs). This retrospective study involved 200 eyes of 100 patients who underwent surgery for bilateral age-related cataract using an enhanced monofocal IOL (TECNIS Eyhance). The dominant eye was identified before surgery. Based on patients’ preferences, they were divided into mini-monovision (dominant eye for distance and non-dominant eye for near with 1.0 D anisometropia), crossed mini-monovision (dominant eye for near and non-dominant eye for distance with 1.0 D anisometropia), or bilateral emmetropia groups. There were 32 patients in the mini-monovision group, 28 in the crossed mini-monovision group, and 40 in the emmetropia group. While binocular distance visual acuity was not different among groups, intermediate and near visual acuity was significantly better in the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups than in the emmetropia group (p < 0.001). The severity of glare and halo, as well as the level of patient satisfaction, did not differ between groups. The rate of spectacle independence was significantly higher in the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups than in the emmetropia group (p = 0.008). Mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision approaches using enhanced monofocal IOLs are equally effective in enhancing intermediate and near vision without compromising distance vision, leading to reduced spectacle dependence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread use of hand-held digital devices and computers in modern society underscores the growing importance of high-quality intermediate vision for optimizing visual function and patient satisfaction following cataract surgery. One of the strategies employed to reduce spectacle dependence in pseudophakic patients is monovision, a technique in which one eye is corrected for distance vision and the other for intermediate or near vision1,2. By leveraging the brain’s ability to adaptively process the different visual inputs from each eye, monovision aims to provide patients with a balanced visual function across various distances. According to the Intelligent Research In Sight (IRIS) Registry, pseudophakic monovision for presbyopia correction was achieved in approximately 34% of patients who underwent bilateral implantation of monofocal intraocular lenses (IOLs), with myopic offsets typically spanning from 0.5 to 1.24 diopters (D)3.

Recently, a mini-monovision strategy using enhanced monofocal IOLs has been reported4,5,6, wherein the non-dominant eyes were targeted to be slightly myopic, ranging from 0.3 D6 to 0.75 D4,5. However, the efficacy of mini-monovision with a larger magnitude of anisometropia with enhanced monofocal IOLs remains unexplored. In addition, while previous studies corrected the dominant eye for distance and the non-dominant eye for intermediate4,5,6, no research has evaluated the outcomes of crossed monovision using enhanced monofocal IOLs, with dominant and non-dominant eyes targeted myopic and emmetropic, respectively. It is known that ocular dominance has plasticity and dominant eyes can be easily shifted by short-term monocular deprivation7,8,9. Moreover, the development of cataract can affect ocular dominance, and cataract surgery itself can lead to a shift in the dominant eye10,11. Several studies using monofocal IOLs indicated that crossed mini-monovision and conventional mini-monovision were comparable in terms of visual function, patient satisfaction, and spectacle independence12,13,14. Similarly, the type of monovision (conventional or crossed) was not significantly related to postoperative satisfaction in patients who received refractive surgery15. In the current study, we compared the visual outcomes and patient satisfaction among pseudophakic patients treated with mini-monovision, crossed mini-monovision, and bilateral emmetropia strategies using enhanced monofocal IOLs.

Patients and methods

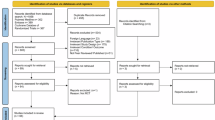

Patients

A retrospective review of medical records was undertaken for 100 patients who had undergone surgery for bilateral age-related cataract between June 2021 and July 2023. None of the eyes had ocular or systemic diseases that could affect the surgical outcomes including visual acuity. Exclusion criteria encompassed, but were not limited to, previous cataract or refractive surgery, irregular astigmatism, severe dry eye, systemic inflammation, uncontrolled diabetes, any anticipated secondary procedure, and the use of systemic or topical medications known to affect patient’s vision. After surgery, the patients were followed up for at least 1 month.

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board of Kyoyukai RiverSide Clinic (registration number 13000005) approved the study protocol. All patients provided informed consent before undergoing treatments. The committee at Kyoyukai RiverSide Clinic determined that additional patient informed consent was not necessary for the use of their medical record data in this retrospective study, in accordance with the Japanese Guidelines for Epidemiologic Study issued by the Japanese Government.

Surgery and intraocular lens

Phacoemulsification and implantation of an IOL (TECNIS Eyhance, Johnson & Johnson Surgical Vision, Santa Ana, CA) were performed in all eyes by a single surgeon (Y. F.). The TECNIS Eyhance IOL is a single-piece, biconvex, acrylic hydrophobic foldable posterior chamber lens with a total diameter of 13.0 mm and an optic diameter of 6.0 mm. It has a refractive optical design with a higher-order aspheric anterior surface that creates a continuous power profile (the power increases continuously from the periphery to the center of the lens), which is intended to extend the depth of focus, thus improving vision for intermediate tasks compared with a standard monofocal IOL16,17,18. In the current study, a toric version of this IOL was utilized to compensate for preoperative corneal astigmatism when recommended by the online calculator. The bilateral surgeries were carried out sequentially, with a one-week interval between each procedure. Prior to surgery, each patient’s dominant eye was identified using the hole-in-card test19.

Target refraction was determined based on patients’ preferences after discussions on the pros and cons of mini-monovision versus emmetropia. Patients opting for bilateral emmetropia had both eyes aimed at plano refraction (emmetropia group). For those preferring mini-monovision, irrespective of ocular dominance, the eye with poorer corrected visual acuity was operated on first. The patients were asked whether they would like to have the first eye corrected for distance or near. In principle, subjects with preoperative hyperopia were advised distance correction, and those with preoperative myopia were suggested near correction, though the final decision was based on patients’ preferences. The second eye was targeted with an anisometropia of 1.0 D. Cases in which the dominant eye was corrected for distance were categorized into the mini-monovision group, while those with the non-dominant eye aimed for distance were placed in the crossed mini-monovision group.

Examinations

Preoperatively, patients underwent standard eye examinations, including assessments of visual acuity, intraocular pressure, and determination of ocular dominance using the hole-in-card test19. One month after the second eye surgery, comprehensive ocular evaluations were performed. The postoperative assessment included manifest refraction, both binocular and monocular corrected and uncorrected distance visual acuity (CDVA and UDVA, respectively), uncorrected intermediate visual acuity at 70 cm (UIVA), and uncorrected near visual acuity at 40 cm (UNVA). Ocular dominance was reassessed after surgery. Patients reported on the severity of photic phenomena. The intensity of glare and halo was graded and categorized using a four-point scale: not bothered at all, bothered a little bit, bothered somewhat, and bothered quite a bit20. Overall satisfaction with surgical outcomes was queried as follows, very high, high, medium, low, and very low. The level of satisfaction was also assessed separately for distance, intermediate, and near vision. The need for spectacles after surgery was inquired, and any intraoperative or postoperative complications were documented throughout the study.

In the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups, patients were asked whether they were bothered by the difference in focus between two eyes and whether they had difficulty perceiving depth.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified. For comparisons between two groups, the Mann-Whitney U-test was utilized. When assessing differences in numerical data across three groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test adjusted with the Bonferroni correction was performed. Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test to assess incidence rates. For the analysis of contingency tables with ordinality, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Among the 100 patients included in the study, 32 were assigned to the mini-monovision group, 28 to the crossed mini-monovision group, and 40 to the emmetropia group. Their preoperative background data are outlined in Table 1. The subjects who opted for emmetropia were significantly older and more hyperopic than those who chose mini-monovision. In the mini-monovision, cross mini-monovision, and emmetropia groups, the first operated eye, which was the worse eye, was the non-dominant eye in 41%, 78%, and 60% of cases, respectively.

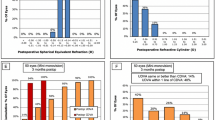

The postoperative refraction is summarized in Table 2. The binocular uncorrected visual acuity was compared among the three groups (Fig. 1). UDVA was not significantly different between groups, but both mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups showed significantly better UIVA and UNVA than the emmetropia group (p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences between the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups at all distances, from near to far.

Binocular uncorrected visual acuity (logMAR). Both mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups showed significantly better UIVA and UNVA than the emmetropia group (p < 0.001, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). UNVA: uncorrected near visual acuity, UIVA: uncorrected intermediate visual acuity, UDVA: uncorrected distance visual acuity.

The monocular uncorrected visual acuity is shown in Fig. 2; Table 3. Eyes targeted for distance vision demonstrated significantly better UDVA than those aimed for near vision (p < 0.001), but UIVA and UNVA were significantly worse in the distance-targeted eyes than in the near-targeted eyes (p < 0.001). The distance-targeted eyes in all three groups showed almost an identical pattern, and the near-targeted eyes in the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups showed similar values across all distances.

Monocular uncorrected visual acuity (logMAR). Eyes targeted for distance vision demonstrated significantly better UDVA than those aimed for near vision (p < 0.001, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction), while UIVA and UNVA were significantly worse in the distance-targeted eyes than in the near-targeted eyes (p < 0.001). UNVA: uncorrected near visual acuity, UIVA: uncorrected intermediate visual acuity, UDVA: uncorrected distance visual acuity.

Patients’ subjective evaluations regarding glare, halo, and satisfaction are shown in Table 4. There were no statistically significant differences in the level of photic phenomena and satisfaction among the groups. The subjective assessments of focus differences between eyes and depth perception were not different between the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups. The rates of spectacle independence were 43.8% (14/32), 57.1% (16/28), and 37.5% (15/40) in the mini-monovision, crossed mini-monovision, and emmetropia groups, respectively. The differences in spectacle independence rates among the groups were statistically significant (p = 0.008), with the emmetropia group showing the lowest rate.

Following surgery, ocular dominance was flipped in one patient each in the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups. These shifts in ocular dominance did not affect the aforementioned outcomes of this study.

Discussion

Conventional monovision using monofocal IOLs is typically defined as targeting one eye for distance vision and the other eye with a myopic correction of -2.50 D to -2.75 D for near vision11. Monovision relies on a neuroadaptation process in which the brain uses distant images from one eye and near images from the other eye to achieve a wider range of binocular functional vision21. However, a substantial amount of anisometropia requires a greater degree of neural adaptation, and a relative decrease in stereopsis may reduce patient satisfaction22. Successful application of monovision requires effective intraocular blur suppression, which may not be achievable for every patient. Furthermore, a decrease in contrast sensitivity at high spatial frequencies, asthenopia, and impaired depth perception are common reasons for the failure of conventional monovision23. To address these issues, mini-monovision approaches aim to correct the near eye between − 0.75 D and − 1.25 D, providing patients with better stereopsis but still requiring spectacle wear for certain near tasks11,23,24.

In the current study, we evaluated the efficacy of mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision using enhanced monofocal IOLs (Eyhance) with a -1.0 D anisometropia between two eyes. Previous studies have explored mini-monovision with a smaller degree of anisometropia using similar IOLs4,5. Sandoval et al.5 demonstrated that patients treated with mini-monovision of -0.6 D in the non-dominant eye exhibited superior binocular UIVA and UNVA compared to those who received bilateral emmetropia treatment, with average improvements of one line at both intermediate and near distances. Park et al.4 found that a -0.75 D mini-monovision in the non-dominant eye significantly enhanced binocular UNVA, but not UIVA, with the mini-monovision group showing binocular UIVA of 0.12 ± 0.09 logMAR and UNVA of 0.06 ± 0.06 logMAR. Our study indicated that the mini-monovision strategy with a 1.0 D anisometropia significantly improved UIVA by one line and UNVA by two lines. In the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups, binocular UIVA was − 0.04 ± 0.08 logMAR and − 0.04 ± 0.10 logMAR, respectively, and binocular UNVA was 0.10 ± 0.12 logMAR and 0.09 ± 0.13 logMAR, respectively, which outperform previous study outcomes that were conducted with a smaller magnitude of anisometropia. In addition, the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision approaches did not negatively impact patient satisfaction and the degree of dysphotopsia. The UDVA was maintained, and spectacle dependence was significantly reduced. Thus, mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision with a 1.0 D difference between both eyes can be an efficient strategy to extend the depth of focus.

Conventional pseudophakic monovision adjusts the dominant eye for distance and the non-dominant eye for near, under the assumption that it is easier to suppress blur in the non-dominant eye than in the dominant eye1,11. Conversely, other studies have evaluated the opposite design, correcting the dominant eye for near vision and the non-dominant eye for distance vision, known as crossed monovision12,13. Zhang et al.12 reported that crossed pseudophakic mini-monovision yielded similar patient satisfaction and spectacle independence to conventional monovision in cases with mild anisometropia (1.12 to 1.19 D). Similarly, Kim et al.13 found that the clinical results of crossed mini-monovision were not significantly different from those of conventional mini-monovision. Comparable results were also reported in highly myopic eyes14. However, these studies were conducted using monofocal IOLs, and there have been no reports on crossed monovision or crossed mini-monovision using enhanced monofocal IOLs. In our study, we found that visual acuity from distance to near was comparable between the mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision groups. There was no discomfort due to anisometropia in either group. The two groups showed comparable results in spectacle independence, overall satisfaction, satisfaction level at each distance, degree of dysphotopsia, and depth perception.

Identifying true ocular dominance in cataract patients can be challenging. The interplay between ocular dominance and cataracts is intricate, influenced by factors like cerebral cortex regulation, neural activity, and various molecular mechanisms7,11. The extent to which ocular dominance in individuals with cataracts accurately mirrors the cerebral cortex’s state remains a subject of debate. Dominance may shift due to binocular competition, arising from differences in lens opacity or changes in the optical media following cataract surgery. It may be essential to consider the dominant eye’s status before cataract development and understand the impact and timing of vision loss caused by cataracts. Consequently, determining the dominant eye based on a single assessment immediately before surgery is not reliable. Therefore, emphasizing ocular dominance is less critical, as both mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision surgeries can yield similar visual outcomes and patient satisfaction levels as indicated by the current study.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, due to the non-randomized and retrospective design of this study, the background data were not homogeneous among groups. The subjects who opted for emmetropia were significantly older and more hyperopic than those who chose mini-monovision. This was probably because younger patients were more eager to pursue spectacle independence and more likely to understand the characteristics of mini-monovision. Myopic patients might place more importance on intermediate and near vision than hyperopic patients. Secondly, several important examinations were lacking, including measurements of defocus curve, contrast sensitivity, and stereopsis. These parameters would have allowed for more detailed analyses of visual function in our patients. Lastly, the postoperative examinations were carried out at one month postoperatively, and longer follow-up data were not available.

In conclusion, we compared the visual outcomes and patient satisfaction of mini-monovision, crossed mini-monovision, and bilateral emmetropia using enhanced monofocal IOLs. Both mini-monovision and crossed mini-monovision using enhanced monofocal IOLs significantly improved intermediate and near vision without compromising distance vision or negatively affecting patient subjective perceptions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Boerner, C. F. & Thrasher, B. H. Results of monovision correction in bilateral pseudophakes. J. Am. Intraocul Implant Soc. 10, 49–50 (1984).

Goldberg, D. G., Goldberg, M. H., Shah, R., Meagher, J. N. & Ailani, H. Pseudophakic mini-monovision: high patient satisfaction, reduced spectacle dependence, and low cost. BMC Ophthalmol. 18, 293 (2018).

Bafna, S., Gu, X., Fevrier, H. & Merchea, M. IRIS® Registry (Intelligent Research in Sight) analysis of the incidence of monovision in cataract patients with bilateral monofocal intraocular lens implantation. Clin. Ophthalmol.17, 3123–3129 (2023).

Park, E. S. et al. Visual outcomes, spectacle independence, and patient satisfaction of pseudophakic mini-monovision using a new monofocal intraocular lens. Sci. Rep. 12, 21716 (2022).

Sandoval, H. P., Potvin, R. & Solomon, K. D. Comparing visual performance and subjective outcomes with an enhanced monofocal intraocular lens when targeted for emmetropia or monovision. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 3693–3702 (2023).

Beltraminelli, T., Rizzato, A., Toniolo, K., Galli, A. & Menghini, M. Comparison of visual performances of enhanced monofocal versus standard monofocal IOLs in a mini-monovision approach. BMC Ophthalmol. 23, 170 (2023).

Chadnova, E., Reynaud, A., Clavagnier, S. & Hess, R. F. Short-term monocular occlusion produces changes in ocular dominance by a reciprocal modulation of interocular inhibition. Sci. Rep. 7, 41747 (2017).

Min, S. H., Baldwin, A. S., Reynaud, A. & Hess, R. F. The shift in ocular dominance from short-term monocular deprivation exhibits no dependence on duration of deprivation. Sci. Rep. 8, 17083 (2018).

Zou, L., Zhou, C., Hess, R. F., Zhou, J. & Min, S. H. Daily dose-response from short-term monocular deprivation in adult humans. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. (2024). Epub ahead of print.

Schwartz, R. & Yatziv, Y. The effect of cataract surgery on ocular dominance. Clin. Ophthalmol. 9, 2329–2333 (2015).

Song, T. & Duan, X. Ocular dominance in cataract surgery: research status and progress. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 262, 33–41 (2024).

Zhang, F., Sugar, A., Arbisser, L., Jacobsen, G. & Artico, J. Crossed versus conventional pseudophakic monovision: patient satisfaction, visual function, and spectacle independence. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 41, 1845–1854 (2015).

Kim, J., Shin, H. J., Kim, H. C. & Shin, K. C. Comparison of conventional versus crossed monovision in pseudophakia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 99, 391–395 (2015).

Xun, Y., Wan, W., Jiang, L. & Hu, K. Crossed versus conventional pseudophakic monovision for high myopic eyes: a prospective, randomized pilot study. BMC Ophthalmol. 20, 447 (2020).

Jain, S., Ou, R. & Azar, D. T. Monovision outcomes in presbyopic individuals after refractive surgery. Ophthalmology 108, 1430–1433 (2001).

Tognetto, D. et al. Surface profiles of new-generation IOLs with improved intermediate vision. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 46, 902–906 (2020).

Vega, F. et al. Optical performance of a monofocal intraocular lens designed to extend depth of focus. J. Refract. Surg. 36, 625–632 (2020).

Mencucci, R. et al. Visual outcome, optical quality and patients’ satisfaction with a new monofocal intraocular lens, enhanced for intermediate vision: preliminary results. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 46, 378–387 (2020).

Seijas, O. et al. Ocular dominance diagnosis and its influence in monovision. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 144, 209–216 (2007).

Lasch, K. et al. Development and validation of a visual symptom-specific patient-reported outcomes instrument for adults with cataract intraocular lens implants. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 237, 91–103 (2022).

Pepin, S. M. Neuroadaptation of presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 19, 10–12 (2008).

Ito, M., Shimizu, K., Niida, T., Amano, R. & Ishikawa, H. Binocular function in patients with pseudophakic monovision. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 40, 1349–1354 (2014).

Mahrous, A., Ciralsky, J. B. & Lai, E. C. Revisiting monovision for presbyopia. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 29, 313–317 (2018).

Hayashi, K., Ogawa, S., Manabe, S. & Yoshimura, K. Binocular visual function of modified pseudophakic monovision. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 159, 232–240 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F. designed the study described here. Y.F., Y.N., and E.I. recruited participants and collected data. T.O. performed statistical analyses, drafted the main manuscript text, and prepared figures. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Oshika is a scientific advisor to Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Johnson & Johnson Vision, and HOYA. Dr. Oshika has received grant supports from Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Johnson & Johnson Vision, and HOYA. None of the other authors has any financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fujita, Y., Nomura, Y., Itami, E. et al. A comparative study of mini-monovision, crossed mini-monovision, and emmetropia with enhanced monofocal intraocular lenses. Sci Rep 15, 916 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80663-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80663-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative visual and refractive analysis of two enhanced monofocal intraocular lenses

BMC Ophthalmology (2026)