Abstract

Hyperpigmentation, a dermatological concern caused by increased melanin production, affects many people worldwide. Traditional skin-brightening products target inhibition of cellular tyrosinase activity but often contain harmful toxicants. Oxyresveratrol (OXR) is a robust tyrosinase inhibitor, but its instability, poor water solubility, and low skin permeation limit its use. This study aimed to overcome these challenges by modifying OXR to dihydrooxyresverstrol (DHO) and encapsulating both compounds into nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs). The developed NLCs loaded with OXR (OXR-NLC) and DHO (DHO-NLC) achieve desirable physicochemical properties, high percentages of entrapment efficiency, and stability for at least three months during 4–40 ℃ of storage. DHO itself and NLC formulation of OXR dramatically enhanced the photostability of OXR. Additionally, NLC formulations significantly promoted controlled release and facilitated penetration through the skin-like hydrophobic membrane of OXR and DHO. Importantly, these NLC formulations exhibited no cytotoxicity on human keratinocyte cells up to 500 µg/mL and effectively reduced melanogenesis in B16F10 cells. Our findings indicate that DHO-loaded NLC offers a promising strategy for developing cosmeceutical products to address hyperpigmentation and promote skin lightening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hyperpigmentation is a common dermatological condition characterized by the darkening of certain skin areas due to excessive melanin production1,2. This process is triggered by numerous factors such as sun exposure, aging, skin inflammation, melasma, and certain medications2,3,4,5. Although typical hyperpigmentation disorders (for example: melasma, solar lentigines, ephelides, and post-inflammatory) are harmless and often do not require medical treatment, skin-brightening cosmeceuticals are widely used as first-line therapies2,5,6. The active ingredients in these products are mainly purposeful in inhibiting the activity of tyrosinase, which is the key enzyme of the melanin biosynthetic pathway in melanocytes2,5,7. However, various commercial skin-lightening products include harmful ingredients such as mercury derivatives, hydroquinone, corticosteroids, resorcinol, and retinoids, which can cause acute toxicity2,5,7. Alternatively, less toxic agents like vitamin C, kojic acid, and α-arbutin, require high doses for effective melanin inhibition2,5,7. As a result, searching for effective and safer tyrosinase inhibitors is ongoing.

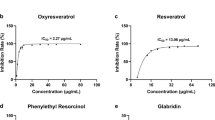

Oxyresveratrol (OXR) is naturally abundant in Artocarpus plants, mulberries, etc8,9. OXR is similar to polyhydroxy trans-stilbenes such as resveratrol and piceatannol10, exhibiting a wide range of medicinal properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, anti-cancer, anti-aging, and depigmentation effects8,11,12,13,14. Among its remarkable attributes, OXR stands out as one of the most potent tyrosinase inhibitors, demonstrating 33- and 45.5-fold greater tyrosinase inhibitory efficacy than kojic acid and resveratrol, respectively15. It effectively suppresses the conversion of L-tyrosine and L-dopa to dopachrome by inhibiting both monophenolase and diphenolase activities of tyrosinase in an irreversible non-competitive manner15,16. However, the poor permeability and aqueous solubility of polyphenolic compounds limit their effectiveness due to decreased skin penetration and drug absorption rates17,18,19. Additionally, heat and ultraviolet or visible light can rapidly induce trans–cis isomerization and accelerate the oxidative degradation and discoloration of stilbenes, leading to instability, shortened shelf life, and decreased pharmacological effectiveness when exposed to air or light over time20,21,22,23. These huge drawbacks limit the use of OXR for cosmeceutical applications and clinical studies.

Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs), second-generation lipid nanocarriers, offer a combination of stability, efficacy, and safety that makes them superior to other lipid-based nanocarriers like SLNs, liposomes, niosomes, and nanocrystals for topical and transdermal applications24,25. The matrix of NLCs comprises the blended mixture of solid lipid and liquid lipid stabilized by emulsifiers24,26. The liquid lipid plays a crucial in NLCs by advancing several key properties over conventional lipid-based nanocarriers: Versatile biocompatible and non-toxic liquid lipids can be used for solubilizing and stabilizing bioactive compounds14,26. The incorporation of liquid lipids in NLCs disrupts the perfect crystal structure of solid lipids, which improves the physical stability, prolongs the long-term stability of the formulation and encapsulated active ingredients, and allows for higher loading of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs26. Adjusting the ratio of solid lipid and liquid lipid composition can achieve the desired release kinetics, stability, and texture for specific cosmeceutical applications27,28. Furthermore, the presence of liquid lipids in the NLC matrix increases the fluidity of the carrier, which can enhance its ability to penetrate through the skin barrier and deposition in deeper skin layers26,27,28. This is especially valuable for NLCs for deeper and more targeted delivery through the topical route of active ingredients.

Several issues need to be addressed to overcome the challenges of using OXR as a potential depigmenting agent, particularly chemical instability, poor aqueous solubility, and low skin permeability. In this study, OXR was derivatized to be dihydrooxyresveratrol (DHO), which enhanced its stability and tyrosinase inhibitory effect in vitro. Additionally, nanostructured lipid carriers encapsulating these two potential tyrosinase inhibitors were developed, and their physicochemical properties, morphology, and cytotoxicity were further characterized. We also demonstrated the long-term stability, photostability, improvement of skin membrane permeation, and anti-melanogenesis properties of OXR- and DHO-loaded NLCs.

Methods

Materials

Artocarpus lakoocha extract ordered from China was used for isolating oxyresveratrol. Palladium/charcoal (10%Pd) was acquired from BDH laboratory supplies (UK). Olivem 1000 was obtained from Forecus (Thailand). Miglyol C-T7 (triheptanoin) was purchased from The Sun Chemical (Thailand). Tween 80 was purchased from Croda (Singapore). Microcare PHC, a combination of phenoxyethanol and chlorophenesin, was sourced from Chemico (Thailand). α-Melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and 3,4-Dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (L-dopa) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Singapore). Kojic acid was acquired from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Singapore). Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit was sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Invitrogen (USA).

Isolation of OXR and synthesis of DHO

Oxyresveratrol (OXR) was purified from extract of Artocarpus lacucha by using silica gel column chromatography and a maximum of 20% CH3OH in CH2Cl2 for gradient elution. The purity of isolated OXR was investigated by using HPLC, as described in the section HPLC analysis. The obtained OXR was further used for synthesis of dihydrooxyresveratrol (DHO) using a slightly modified method as described in Faragher et al. (2011)29. In detail, the process involved catalytic hydrogenation of OXR (0.41 mmol, 100 mg) with 10% Pd/C catalyst (0.03 mmol, 3 mg) in C2H5OH (10 mL) at room temperature and atmospheric pressure for 1 h. After the reaction was complete, the catalyst was removed by filtration through Whatman filter paper no.1. The filtrate was then evaporated to obtain a solid residue of DHO. The chemical structures were elucidated using 1H and 13C NMR (JEOL JNM-ECZR 500 MHz).

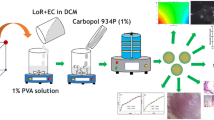

Preparation of OXR- and DHO-loaded NLCs

The NLCs were formulated using the modified method described in Pimentel-Moral et al. (2019) and Yostawonkul et al. (2017)30,31. All the compositions with appropriate ratios are presented in Table 1. Briefly, both lipid and aqueous phases were heated separately at 80 °C. Then, the mixture of aqueous phase was slowly added into the melted lipid phase, and followed by ultrasonication using a Sonics Vibra-Cell ultrasonic liquid processor (Sonics & Materials, INC, USA) at 20% amplitude for 3 min to form nanoemulsion. The suspension of nanoformulations was then cooled to room temperature to solidify the nanoparticles. The hydrophilic–lipophilic balance (HLB) of a surfactant mixture was then calculated as described by Wu et al. (2021)32.

Characterization of nanoparticles and their stability

Measurements of particle size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential

The particle sizes, size distribution, and zeta potential of the formulated nanoparticles were determined using the dynamic light scattering (DLS) technique with Zetasizer Nano ZX (Malvern Instruments, UK). All samples were diluted 100 times with deionized water before measurement at 25 ℃.

Determination of encapsulation efficiency and loading capacity

The encapsulation efficiency (%EE) and the drug loading capacity (%LC) of OXR- or DHO-loaded NLC were determined as previously described by Pimentel-Moral et al. (2019)30. Firstly, each nanoformulation was diluted to 10% in deionized water. Non-encapsulated OXR/DHO was separated using Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter 3 kDa MWCO (Millipore Sigma) and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 1 h at room temperature. The amount of non-encapsulated OXR or DHO in the supernatant was determined using HPLC, as described in the section HPLC analysis. The amount of OXR or DHO was calculated using standard calibration curve. Subsequently, %EE and %LC were calculated using the Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis

The morphology of nanoparticles was investigated using JEOL JEM-1400 series 120 kV transmission electron microscope (Jeol, USA). Each NLC formulation was diluted to 1% in deionized water and spotted onto a copper grid (200 mesh). The samples were subjected to negative staining using UranyLess (Electron Microscopy Sciences, USA) and dyed prior to TEM imaging.

Evaluation of nanoparticle long-term stability

To investigate nanoparticle stability during long-term storage, NLC formulations were kept at 4, 25, and 40 °C for three months. Size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential values were measured monthly as described in the section HPLC analysis.

Photostability testing

The aqueous solutions (5% propylene glycol) and NLC formulations of OXR and DHO with approximately 3 mg/mL drugs were prepared and stored at room temperature in dark and light exposure conditions for 15 weeks. Each sample was sampled and diluted 100-time in CH3OH (HPLC grade). The remaining amounts of OXR and DHO were analyzed using HPLC.

In vitro drug release

The release profiles of OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC were evaluated by measuring diffusion pass through dialysis membrane to phosphate buffer saline (PBS). The NLC formulations and aqueous suspension (5% PEG) of free drugs (equivalent to 2 mg/mL drug) were loaded into SnakeSkin™ 3.5 K MWCO dialysis tubing, 16 mm I.D. (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and immersed in 30 mL of release medium (PBS pH 7.4) at 32 °C under stirring. The release medium (1 mL) was collected at time points of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h, and the same volume of fresh medium was replaced. The concentration of released OXR and DHO was analyzed by HPLC.

In vitro drug permeation study

The permeability through the skin-like hydrophobic membrane of OXR-NLC, DHO-NLC, and aqueous suspension (5%PEG) of free drugs was examined by Franz diffusion cell using Automated Transdermal Diffusion Cell Sampling System 913A-12 (Logan Instruments, China). The polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane, 0.45 μm (Thermo Scientific, USA), was used in this study to mimic the skin barrier of stratum corneum. PVDF membrane was mounted on a diffusion cell assembly having a diffusion area of 1.54 cm2. The receptor chambers consisted of 12 mL of PBS, pH 7.4 as receptor medium which were agitated at 100 rpm and maintained at 32 °C. The NLC formulation or free drug aqueous suspension (1 mL) was placed on the membrane in the donor compartment. The receptor medium (1 mL) was withdrawn at specific time intervals and an equal volume of fresh medium was replaced immediately. The concentration of diffused OXR or DHO was analyzed by using HPLC. The cumulative drug permeation was subsequently calculated following Eq. (3):

where V0, total volume of media in receptor cells; Vi, sample volume; Cn, drug concentrations in the receptor cells; Ci, concentration of the extraction samples (μg/mL); A, transporting area (cm2).

In vitro cytotoxicity test

B16F10 and HaCaT cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium)-4.5 g/L glucose (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, USA), 100 units/mL of penicillin, 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, 0.25 µg/mL of amphotericin B (Gibco, USA). After culturing overnight, cells were treated with varying equivalent doses of free drug and drug-loaded nanoparticles for 48 h. In addition, 0.5% DMSO and empty nanoparticles were used as the control for toxicity evaluation of vehicle and carriers, respectively. Then, cell viability was measured using MTT. Briefly, each well was replaced by 1 mg/mL MTT solution and further incubated for 3 h at 37 ℃. Then, MTT solution was removed, formazan crystal was solubilized using DMSO, and further measured absorbance at wavelength 570 nm by BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek, USA). The cell viability was calculated as a relative percentage of the absorbance of the control group according to Eq. (4).

Measurement of intracellular melanin content

Intracellular melanin content was determined using methods modified from Yao et al. (2013)33 and Oh et al. (2017)34. B16F10 cells were seeded onto a 6-well plate and cultured overnight. Cells were then treated with various concentrations of free drug and drug-loaded NLC in the presence or absence of 1 μM α-MSH for 48 h. Kojic acid was used as a positive control. The cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, and spun down. Cell pellets were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) containing 1%(v/v) triton X-100. After centrifuging at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, supernatants were collected to further evaluate cellular tyrosinase activity. Cell pellet was dried at 90 °C and melanin was further solubilized in 1 M NaOH containing 10% DMSO at 90 °C for 1 h and cell lysate was then subsequently transferred onto 96-well plate. The melanin content was measured at 405 nm using BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek, USA). The protein content of each treatment was determined using Pierce BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Scientific, USA). Melanin content was normalized with the protein concentrations (absorbance/μg protein) prior to calculating relative melanin content, to ensure that the melanin content obtained from each experimental group was produced from an equal number of cells.

Measurement of cellular tyrosinase activity

Cellular tyrosinase activity was performed with a modified method described by Yao et al. (2013)33 and Oh et al. (2017)34. After obtaining the cell supernatants from previous section, 50 μL of lysate and 2 mM L-dopa (substrate) were added into a 96-well plate, and further incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The wells containing 50 μL of lysis buffer and substrate were used as a control. The absorbance of dopachrome formation was measured at wavelength 405 nm using a microplate reader. Absorbance 405 was normalized with protein concentration prior to calculating tyrosinase inhibitory activity, to ensure the total protein used in each reaction was produced and harvested from the same amount of tested cells.

HPLC analysis

Quantitative analysis of OXR and DHO was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) Nexera LC-40 (Shimadzu) with a photodiode array detector. The Shim-pack GIST C18 column (5 µm, 250 × 4.6 mm) was used for separating OXR and DHO under isocratic conditions using CH3OH and H2O of a ratio 70:30 (v/v) as mobile phase. The eluent flow rate was set at 1 mL/min and the column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. UV wavelengths 300 and 286 nm were used for OXR and DHO detection, respectively. The precision, LOD, and LOQ of the method used for HPLC analysis are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4.

Statistical analysis

Data presented in this study were reported as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). Statistical comparison was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis among multiple groups. Statistically significant differences were considered at p-value < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Isolation of oxyresveratrol and synthesis of dihydrooxyresveratrol

One of our goals in this study was to improve stability and delay the degradation of trans-OXR by converting it to DHO. As shown in Fig. 1, hydrogenation of the internal olefin of OXR was achieved and DHO (> 99% yield) was obtained. In our preliminary study, DHO remarkably exhibited mushroom tyrosinase inhibitory activity with IC50 (0.05 μM) approximately 6-time greater than OXR (IC50: 0.3 μM). Both OXR and DHO exhibited identical distances traveled on thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates and retention times when analyzed using HPLC. However, after vanillin staining, different shades of pink between OXR and DHO could be distinguished on TLC plate (Fig. 1B). The correct chemical structures of the twos were confirmed using 1H and 13C NMR analysis. Specifically, the 1H NMR chromatogram of DHO contained 14 protons in total which have an additional 2 protons from positions C7 and C8 of methyl group signal that was absent in OXR (12 protons in total). Meanwhile, 13C NMR chromatograms showed an identical number of carbons for both OXR and DHO. Furthermore, the NMR results showed clear and high-intensity signals confirming the purity of the obtained OXR and DHO. All HPLC and NMR chromatograms are presented in the supporting information.

Preparation of OXR- and DHO-loaded NLC

NLC loaded with either OXR or DHO was prepared using a simple ultrasonication method. The naturally safe components and appropriate ratios used in NLC formulations were obtained from preliminary optimizations (see Table 1 and supplementary section 3). In this study, olivem 1000 (HLB 9)35 and miglyol C-T7 (HLB 11) were compatible solid and liquid lipids used for blending the hydrophobic nature of OXR or DHO in the matrix of NLC. The maximum amount of OXR or DHO that could completely dissolve and blend in a mixture of lipid phase was 0.3% (w/w). Tween 80, a non-ionic and low-toxic substance with an HLB of 15, was chosen as the surfactant for the NLC formulations. By using 4% (w/w) Tween 80, the NLC formulations exhibited desirable physical properties and showed no phase separation. As shown in Fig. 1C, the milky to translucent dispersion with a final HBL number of approximately 11.9 was obtained from the combination of those surfactants, resulting in an oil-in-water emulsion for this NLC formulation.

Characterization of particle size, size distribution, and surface charge of NLCs

After developing NLCs, crucial parameters influencing efficient drug delivery, including particle size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential, were assessed using the dynamic light scattering approach. The results, as shown in Table 2, indicated that both OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC exhibited small particle sizes (113.07 ± 1.27 and 110.27 ± 1.67 nm, respectively), which are appropriate for deep skin penetration36. Additionally, the narrow size distribution (PDI < 0.3) further confirms the consistency and quality of the NLC preparation. Furthermore, the highly negative zeta potentials (< −30 mV) of the NLC formulations suggest strong electrostatic repulsion between particles, effectively minimizing the risk of lipid agglomeration.

Encapsulation efficiency and loading capacity of NLCs

The use of 0.3% of either OXR or DHO for formulating OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC was reproducible and exhibited a high encapsulation efficiency of more than 97%. Whereas, the loading capacities of OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC were roughly 8.16 ± 0.12 and 5.62 ± 0.00%, respectively (see Table 2). Liquid lipid inside an unorganized matrix of NLC plays a key role in determining drug loading capacity26. To improve drug loading capacity of NLCs loaded with either OXR or DHO, compatible liquid lipids or solubilizers that increase the dissolution of OXR and DHO can be used37. However, our NLC formulations exhibited higher encapsulation efficiency38,39, and an increase in drug loading capability (LC: ̴8%) compared to a previous study (LC: ̴5%) with the same amount of OXR used39.

Morphology determination of NLCs

TEM photographs revealed the morphology of Blank-NLC, OXR-NLC, and DHO-NLC was spherical or ellipse in shape with their sizes ranging from 100 to 250 nm (see Fig. 1D–F). The nanostructures in the NLC matrix can be observed in Fig. 1F. Apart from particle sizes, the differences in particle shapes also influence the capability of skin penetration40, but modifying the typical shape of lipid-based nanocarriers is difficult.

Long-term stability testing of NLC formulations

We then investigated the long-term stability of formulated OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC to confirm whether their physical and chemical qualities were maintained during storage at 4, 25, and 40 ˚C for 3 months by measuring the particle size, PDI, and Zeta potential. As shown in the supplementary information (Fig. S5A–C), all formulations were considerably stable with no significant change observed in particle size, PDI, and zeta potential after storage at different conditions for three months. Additionally, no phase separation and lipid agglomeration appeared in any of NLC formulations (supplementary Fig. S5D). However, gradual size expansion of DHO-NLC was found when stored at 40 ˚C. This phenomenon can be caused by destabilization of the lipids, and reduction of emulsifier microviscosity of the system at high temperature41. Additionally, previous studies demonstrated the prolonged stability of NLC formulations when preserved at low temperatures39,42. Herein, the results suggest that the obtained NLC formulations loaded with 0.3% OXR or DHO are highly stable and able to retain critical characteristics even after preservation at 4, 25, and 40 ˚C for at least three months.

Photostability study

OXR is susceptible to photodegradation. Exposure of trans-stilbene to light can lead to alterations in physical and chemical properties43,44, as well as pharmacological activities and therapeutic efficacy21,45,46. These effects should be considered when incorporating OXR into the products, accompanied by finding the appropriate strategies to minimize photodegradation to maintain product stability.

In this experiment, the photostability of OXR, DHO, and their NLC formulations was monitored at room temperature under light exposure and dark conditions for 15 weeks (Fig. 2). The results revealed that OXR content in aqueous solution dramatically decreased since week two of exposures in both dark and light conditions, and its color turned brown. On the other hand, the NLC formulations of OXR could delay OXR degradation efficiently at initial 5 weeks (Fig. 2A,B). Additionally, DHO itself demonstrated remarkable stability under both dark and light exposure conditions throughout 15 weeks of detection, albeit with a slightly darkened color (Fig. 2A,C). These results indicate that NLC formulations successfully enhanced OXR stability and extended its life cycle. Notably, the derivatization of OXR to DHO proved effective in preventing photo-induced OXR degradation. Optionally, co-encapsulation with antioxidants, such as vitamin C can mitigate the instability and browning effects of OXR47.

Photostability evaluation of OXR, DHO, and their NLCs. (A) The change of physical appearance of aqueous solutions and NLC formulations of OXR and DHO during storage at room temperature in the conditions of with and without light exposure for 15 weeks. The remaining amounts of drugs during 15 weeks were analyzed by using HPLC: Free OXR and OXR-NLC (B), and free DHO and DHO-NLC (C). Data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). Statistical significance: * p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.001 vs remaining amount of drug at 0 week.

In vitro drug release study

The release mechanism of drugs encapsulated in lipid nanocarriers involves both diffusion through the lipid matrix and the erosive and degradative processes affecting the lipid matrix48. Additionally, alterations in pH and temperature can impact the integrity of the lipid membrane which also influences drug release49.

In this study, we investigated the release patterns of OXR and DHO from NLC using the dialysis method. As depicted in Fig. 3A, non-encapsulations of OXR and DHO exhibited an initial burst release behavior within 4 h, with cumulative releases of approximately 76% and 93%, respectively. In contrast, OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC displayed a sustained release pattern, with cumulative releases of OXR and DHO in NLC formulations reaching 15% and 49% at 48 h, respectively.

NLC formulations control the release and enhance the skin-like hydrophobic membrane permeation of OXR and DHO. (A) In vitro release profiles of OXR, DHO, and their NLCs. (B) In vitro permeability of OXR, DHO, and their NLCs through PVDF membrane. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). Statistical significance: *** p < 0.001.

Although an unhurried drug release rate was observed in the in vitro study for OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC, lipid degradation and erosion initiated by intracellular enzymes along with the acidic pH within endosomes and lysosomes can potentially promote drug release once NLC permeates through the stratum corneum and enter the cells50,51. Nevertheless, a reduction in the cumulative amount of free OXR in the release medium appeared when compared to free DHO due to the instability of OXR in neutral pH conditions at room temperature under light exposure52. These findings suggest that the rapid degradation of OXR might contribute to the fast saturation of the cumulative release of free OXR and OXR-NLC when compared to free DHO and DHO-NLC.

Permeation study of OXR/DHO-loaded NLCs

The extremely lipophilic and hydrophobic nature of the human skin surface poses a significant barrier to drug penetration, especially compounds with the same poor solubility as OXR and DHO. In this study, the enhancement of skin penetration of OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC was assessed using the Franz diffusion cell method and a PVDF membrane simulating the hydrophobic property of the stratum corneum53,54.

The results presented in Fig. 3B, clearly demonstrated that both OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC formulations consecutively increased the penetration of OXR and DHO through the membrane compared to free OXR and DHO in aqueous solution. This finding suggested that the NLC system enhances the skin penetration of OXR and DHO, overcoming the barrier presented by the skin’s hydrophobic surface.

The remarkable increase in skin penetration of OXR- and DHO-loaded NLCs can be attributed to several factors. First, the lipid-based NLCs provide a favorable environment for the solubilization and dispersion of hydrophobic drugs like OXR and DHO, thereby facilitating their transport across the lipophilic membrane. Additionally, the NLCs may interact with the stratum corneum lipids, leading to enhanced partitioning and permeation of the encapsulated drugs. Taken together with the sustained-release properties of NLCs (Fig. 3A) may contribute to prolonged drug disposition in the skin’s layers.

Cytotoxicity effect of OXR/DHO-loaded NLCs

The non-toxic concentrations of free drugs and drug-loaded NLCs toward both B16F10 melanoma and human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cells were assessed before investigating their anti-melanogenesis effects. The results indicated that OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC exhibited no cytotoxicity in B16F10 cells at concentrations up to 2,000 μg/mL (equivalent to 6 µg/mL or 24 µM loaded drug) when compared to the untreated control (Fig. 4A). Conversely, free OXR, Blank-NLC, and drug-loaded NLCs showed significant toxicity at concentrations above 500 μg/mL in HaCaT cells (Fig. 4B). As a result, NLC concentrations lower than 500 μg/mL were selected for further evaluation of their anti-melanogenesis properties. Moreover, our NLC system seems to be less toxic in HaCaT cells compared to previous reports. In 2021, Gonçalves and co-workers reported that NLC formulating by using Apifil (solid lipid), Miglyol 812 (oil), and 10% Pluronic F-127 (surfactant) exhibited cytotoxicity at concentrations equal to or higher than 100 µg/mL NLC55. In 2019, Carbone and team demonstrated that essential oil-loaded NLCs containing softisan 100 (solid lipid) and ratio 4:1 of the mixture Kolliphor RH40 (surfactant)/Labrafil (liquid lipid) showed significant cytotoxicity at concentrations higher than 0.05% of loaded drug (equal to 12.5 µg/mL NLCs)56.

The cytotoxic effects of OXR, DHO, and their NLC formulations on the viability of B16F10 melanoma (A) and HaCaT keratinocyte (B) cells. Both cell lines were treated with free OXR, free DHO, Blank NLC, OXR-NLC, and DHO-NLC at various concentrations for 48 h. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n ≥ 3). Significant differences: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs untreated control (100% cell viability).

Evaluation of intracellular melanin content in B16F10 cells

The anti-melanogenesis effects of OXR and DHO, both before and after being formulated into NLCs on anti-melanogenesis properties were further evaluated. Non-toxic concentrations of free drugs and their NLC formulations were used to assess their inhibitory effects on tyrosinase activity against α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH)-induced melanin synthesis in B16F10 cells. As shown in Fig. 5, both free OXR, free DHO, and their NLC formulations significantly reduced intracellular melanin production compared to the untreated control. Previously, Li and coworkers (2020) demonstrated that 1.25 μM of OXR could decrease melanin synthesis and tyrosinase activity in B16 cells by approximately 10% and 45%, respectively57. Similarly, Kim et al. (2012) reported that treatment with 1 μM of OXR reduced melanin synthesis by 50% and tyrosinase activity by 35% B16F10 cells58. Meanwhile, our results showed that B16F10 cells treated with as little as 0.3 μg/mL (1.2 μM) of OXR and its NLC formulation effectively reduced melanin production and tyrosinase activity by over 60 and 30%, respectively, compared to the untreated control. Taken together with our cellular tyrosinase activity results, these findings demonstrate superior anti-melanogenic activity of OXR and DHO, particularly in NLC formulations, compared to previous studies57,58, and other drug-loaded NLC systems59,60.

Effects of OXR, DHO, and their NLC formulations on suppressing melanin production in B16F10 cells. Cells were treated with OXR (A), DHO (B), and their NLC formulations in the presence and absence of α-MSH for 48 h incubation. Cells treated with 0.5% DMSO, α-MSH alone, and 50 µM kojic acid were used as vehicle, untreated, and positive controls, respectively. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). Significant differences: *** p < 0.001.

Evaluation of cellular tyrosinase activity in B16F10 cells

The effect of OXR, DHO, and their NLC formulations on the inhibition of α-MSH-induced melanogenesis was confirmed by assessing cellular tyrosinase activity in B16F10 cells. As shown in Fig. 6, the results exhibited cellular tyrosinase activity decreased significantly in a concentration-dependent manner after treatment with free OXR, free DHO, and their NLC formulations, even at lower concentrations of 100 µg/mL NLCs (equivalent to 0.3 µg/mL free drug). We noticed that higher concentrations of Blank-NLC led to an increase in cellular tyrosinase activity, potentially due to the induction of reactive oxygen species formation within the cells. However, OXR-NLC and DHO-NLC could remarkably defeat this concern , particularly DHO-NLC significantly decreased cellular tyrosinase activity in comparison to free DHO (Fig. 6B). These results highlight the potential of these compounds, when encapsulated in NLCs, as effective agents for inhibiting melanin synthesis. Furthermore, our study revealed the anti-melanogenic activity of DHO and its NLC formulation in B16F10 cells which has never been reported elsewhere.

Effects of OXR, DHO, and their NLC formulations on suppressing cellular tyrosinase activity in B16F10. Cells were treated with OXR (A), DHO (B), and their NLC formulations in the presence and absence of α-MSH for 48 h incubation. Cells treated with 0.5% DMSO, α-MSH alone, and 50 µM kojic acid were used as vehicle, untreated, and positive controls, respectively. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). Significant differences: ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Conclusion

This research successfully addressed several drawbacks associated with OXR for the topical treatment of hyperpigmentation by modifying its chemical structure and encapsulating it into NLCs. After the successful synthesis of DHO, novel NLC formulations were developed using a simple and scalable ultrasonication process, demonstrating desirable characteristics, high encapsulation efficiency, and long-term stability across various temperatures (4 to 40 °C). We showed that DHO significantly enhanced the photostability of OXR. Whereas, NLC formulations prolonged drug release, and greatly improved the penetration of OXR and DHO through skin-simulating lipophilic membranes, compared to free drugs. Furthermore, therapeutic concentrations of OXR- and DHO-loaded NLCs were non-toxic to human keratinocytes and demonstrated effective anti-melanogenesis properties in B16F10 cells. These findings suggest that DHO-loaded NLCs could be integrated into cosmeceutical products for the treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders and for skin brightening. The simplicity of the formulation process (ultrasonication) highlights the potential for scale-up and commercial production of NLCs. Additionally, NLC-based formulations offer a safer and more effective topical delivery system compared to oral routes, reducing systemic side effects while targeting the skin locally. For future therapeutic applications, further investigation into the inhibitory efficacy of these formulations on ultraviolet-induced hyperpigmentation in vivo and ex vivo models is essential. Clinical studies should also be conducted to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and consumer acceptability of DHO-loaded NLCs in larger populations. Successful scale-up of this system could lead to its incorporation into commercial cosmeceutical products, offering a novel solution for addressing hyperpigmentation and achieving skin lightening.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Rathee, P., Kumar, S., Kumar, D., Kumari, B. & Yadav, S. S. Skin hyperpigmentation and its treatment with herbs: an alternative method. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 7, 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-021-00284-6 (2021).

Zhao, W. et al. Potential application of natural bioactive compounds as skin-whitening agents: A review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 21, 6669–6687. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.15437 (2022).

Samson, N., Fink, B. & Matts, P. J. Visible skin condition and perception of human facial appearance. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 32, 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2494.2009.00535.x (2010).

Dereure, O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2, 253–262. https://doi.org/10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006 (2001).

Thawabteh, A. M., Jibreen, A., Karaman, D., Thawabteh, A. & Karaman, R. Skin pigmentation types, causes and treatment—a review. Molecules 28, 4839. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28124839 (2023).

Sarkar, R., Arora, P. & Garg, K. V. Cosmeceuticals for hyperpigmentation: What is available?. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 6, 4–11. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2077.110089 (2013).

Pillaiyar, T., Manickam, M. & Namasivayam, V. Skin whitening agents: medicinal chemistry perspective of tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 32, 403–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/14756366.2016.1256882 (2017).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Morus alba and active compound oxyresveratrol exert anti-inflammatory activity via inhibition of leukocyte migration involving MEK/ERK signaling. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 13, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-13-45 (2013).

Maneechai, S. et al. Quantitative analysis of oxyresveratrol content in Artocarpus lakoocha and ‘Puag-Haad’. Med. Princ. Pract. 18, 223–227. https://doi.org/10.1159/000204354 (2009).

Valletta, A., Iozia, L. M. & Leonelli, F. Impact of environmental factors on stilbene biosynthesis. Plants (Basel) 10, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10010090 (2021).

Chao, J., Yu, M. S., Ho, Y. S., Wang, M. & Chang, R. C. Dietary oxyresveratrol prevents parkinsonian mimetic 6-hydroxydopamine neurotoxicity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 1019–1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.002 (2008).

Choi, B., Kim, S., Jang, B.-G. & Kim, M.-J. Piceatannol, a natural analogue of resveratrol, effectively reduces beta-amyloid levels via activation of alpha-secretase and matrix metalloproteinase-9. J. Funct. Foods 23, 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2016.02.024 (2016).

Rodboon, T., Puchadapirom, P., Okada, S. & Suwannalert, P. Oxyresveratrol from Artocarpus lakoocha Roxb. inhibit melanogenesis in B16 melanoma cells through the role of cellular oxidants. Walailak J. Sci. Tech. 13, 261–270 (2015).

Mascarenhas-Melo, F. et al. Dermatological bioactivities of resveratrol and nanotechnology strategies to boost its efficacy—an updated review. Cosmetics 10, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics10030068 (2023).

Kim, Y. M. et al. Oxyresveratrol and hydroxystilbene compounds. Inhibitory effect on tyrosinase and mechanism of action. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16340–16344. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M200678200 (2002).

Shin, N. H. et al. Oxyresveratrol as the potent inhibitor on dopa oxidase activity of mushroom tyrosinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 243, 801–803. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1998.8169 (1998).

Breuer, C., Wolf, G., Andrabi, S. A., Lorenz, P. & Horn, T. F. Blood-brain barrier permeability to the neuroprotectant oxyresveratrol. Neurosci. Lett. 393, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.081 (2006).

Dhakar, N. K. et al. Comparative evaluation of solubility, cytotoxicity and photostability studies of resveratrol and oxyresveratrol loaded nanosponges. Pharmaceutics 11, 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics11100545 (2019).

Navarro-Orcajada, S. et al. Stilbenes: Characterization, bioactivity, encapsulation and structural modifications. A review of their current limitations and promising approaches. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2045558 (2022).

van den Berg, J. L. et al. Strong, nonresonant radiation enhances cis–trans photoisomerization of stilbene in solution. J. Phys. Chem. A 124, 5999–6008. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.0c02732 (2020).

Ohguchi, K. et al. Effects of hydroxystilbene derivatives on tyrosinase activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 307, 861–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01284-1 (2003).

Park, J. et al. Effects of resveratrol, oxyresveratrol, and their acetylated derivatives on cellular melanogenesis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 306, 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-014-1440-3 (2014).

Silva, C. G. et al. Photochemical and photocatalytic degradation of trans-resveratrol. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 12, 638–644. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2pp25239b (2013).

Javed, S., Mangla, B., Almoshari, Y., Sultan, M. H. & Ahsan, W. Nanostructured lipid carrier system: A compendium of their formulation development approaches, optimization strategies by quality by design, and recent applications in drug delivery. Nanotechnol. Rev. 11, 1744–1777. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2022-0109 (2022).

Yu, Y.-Q., Yang, X., Wu, X.-F. & Fan, Y.-B. Enhancing permeation of drug molecules across the skin via delivery in nanocarriers: Novel strategies for effective transdermal applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2021.646554 (2021).

Khan, S., Sharma, A. & Jain, V. An overview of nanostructured lipid carriers and its application in drug delivery through different routes. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 13, 446–460. https://doi.org/10.34172/apb.2023.056 (2023).

Liu, X. & Zhao, Q. Long-term anesthetic analgesic effects: Comparison of tetracaine loaded polymeric nanoparticles, solid lipid nanoparticles, and nanostructured lipid carriers in vitro and in vivo. Biomed. Pharmacother. 117, 109057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109057 (2019).

Krambeck, K. et al. Design and characterization of Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) and Nanostructured lipid carrier-based hydrogels containing Passiflora edulis seeds oil. Int. J. Pharm. 600, 120444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120444 (2021).

Faragher, R. G. et al. Resveratrol, but not dihydroresveratrol, induces premature senescence in primary human fibroblasts. Age (Dordr) 33, 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-010-9201-5 (2011).

Pimentel-Moral, S. et al. Polyphenols-enriched Hibiscus sabdariffa extract-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC): Optimization by multi-response surface methodology. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 49, 660–667 (2019).

Yostawonkul, J. et al. Nanocarrier-mediated delivery of α-mangostin for non-surgical castration of male animals. Sci. Rep. 7, 16234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16563-3 (2017).

Wu, K.-W. et al. Primaquine loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN), nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC), and nanoemulsion (NE): effect of lipid matrix and surfactant on drug entrapment, in vitro release, and ex vivo hemolysis. AAPS PharmSciTech 22, 240. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-021-02108-5 (2021).

Yao, C., Oh, J. H., Oh, I. G., Park, C. H. & Chung, J. H. [6]-Shogaol inhibits melanogenesis in B16 mouse melanoma cells through activation of the ERK pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 34, 289–294. https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2012.134 (2013).

Oh, T. I. et al. Plumbagin suppresses α-MSH-induced melanogenesis in B16F10 mouse melanoma cells by inhibiting tyrosinase activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020320 (2017).

Portes, D. B., Abeldt, L. W., dos Santos Giubert, C., Endringer, D. C. & Pimentel, E. F. Development of natural cosmetic emulsion using the by-product of Lecythis pisonis seed. Toxicol. Vitro https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2024.105791 (2024).

Mardhiah Adib, Z., Ghanbarzadeh, S., Kouhsoltani, M., Yari Khosroshahi, A. & Hamishehkar, H. The effect of particle size on the deposition of solid lipid nanoparticles in different skin layers: A histological study. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 6, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.15171/apb.2016.06 (2016).

Silva, P. M. et al. Recent advances in oral delivery systems of resveratrol: foreseeing their use in functional foods. Food Funct. 14, 10286–10313. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3FO03065B (2023).

Neves, A. R., Lúcio, M., Martins, S., Lima, J. L. & Reis, S. Novel resveratrol nanodelivery systems based on lipid nanoparticles to enhance its oral bioavailability. Int. J. Nanomed. 8, 177–187. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.S37840 (2013).

Sangsen, Y., Wiwattanawongsa, K., Likhitwitayawuid, K., Sritularak, B. & Wiwattanapatapee, R. Modification of oral absorption of oxyresveratrol using lipid based nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 131, 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.04.055 (2015).

Tak, Y. K., Pal, S., Naoghare, P. K., Rangasamy, S. & Song, J. M. Shape-dependent skin penetration of silver nanoparticles: does it really matter?. Sci. Rep. 5, 16908. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16908 (2015).

Shah, R. M., Eldridge, D. S., Palombo, E. A. & Harding, I. H. Optimisation and stability assessment of solid lipid nanoparticles using particle size and zeta potential. J. Phys. Sci. 25, 59–75 (2014).

Hashemi, F. S., Farzadnia, F., Aghajani, A., Ahmadzadeh NobariAzar, F. & Pezeshki, A. Conjugated linoleic acid loaded nanostructured lipid carrier as a potential antioxidant nanocarrier for food applications. Food Sci. Nutr. 8, 4185–4195. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1712 (2020).

Han, J. et al. Comparative study on properties, structural changes, and isomerization of cis/trans-stilbene under high pressure. J. Phys. Chem. C 126, 16859–16866. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.2c04865 (2022).

Xi, W. et al. A novel stilbene-based organic dye with trans-cis isomer, polymorphism and aggregation-induced emission behavior. Dyes Pigments 122, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2015.06.008 (2015).

Sugihara, K. et al. Metabolic activation of the proestrogens trans-stilbene and trans-stilbene oxide by rat liver microsomes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 167, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1006/taap.2000.8979 (2000).

Huang, T.-T. et al. cis-Resveratrol produces anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting canonical and non-canonical inflammasomes in macrophages. Innate Immun. 20, 735–750. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753425913507096 (2014).

He, J. et al. Oxyresveratrol and ascorbic acid O/W microemulsion: Preparation, characterization, anti-isomerization and potential application as antibrowning agent on fresh-cut lotus root slices. Food Chem. 214, 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.095 (2017).

Ganesan, P. & Narayanasamy, D. Lipid nanoparticles: Different preparation techniques, characterization, hurdles, and strategies for the production of solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers for oral drug delivery. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 6, 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2017.07.002 (2017).

Roy, B. et al. Influence of lipid composition, pH, and temperature on physicochemical properties of liposomes with curcumin as model drug. J. Oleo Sci. 65, 399–411. https://doi.org/10.5650/jos.ess15229 (2016).

Wong, P. T. & Choi, S. K. Mechanisms of drug release in nanotherapeutic delivery systems. Chem. Rev. 115, 3388–3432. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr5004634 (2015).

Kolter, T. & Sandhoff, K. Lysosomal degradation of membrane lipids. FEBS Lett. 584, 1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.021 (2010).

Zupančič, Š, Lavrič, Z. & Kristl, J. Stability and solubility of trans-resveratrol are strongly influenced by pH and temperature. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 93, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.04.002 (2015).

Ottaviani, G., Martel, S. & Carrupt, P.-A. Parallel artificial membrane permeability assay: A new membrane for the fast prediction of passive human skin permeability. J. Med. Chem. 49, 3948–3954. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm060230+ (2006).

Tsanaktsidou, E., Chatzitaki, A.-T., Chatzichristou, A., Fatouros, D. G. & Markopoulou, C. K. A comparative study and prediction of the ex vivo permeation of six vaginally administered drugs across five artificial membranes and vaginal tissue. Molecules 29, 2334. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29102334 (2024).

Gonçalves, C. et al. Lipid nanoparticles containing mixtures of antioxidants to improve skin care and cancer prevention. Pharmaceutics https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13122042 (2021).

Carbone, C. et al. Clotrimazole-loaded mediterranean essential oils NLC: A synergic treatment of candida skin infections. Pharmaceutics https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics11050231 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Oxyresveratrol extracted from Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. inhibits tyrosinase and age pigments in vitro and in vivo. Food Funct. 11, 6595–6607. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0FO01193B (2020).

Kim, J.-K., Park, K.-T., Lee, H.-S., Kim, M. & Lim, Y.-H. Evaluation of the inhibition of mushroom tyrosinase and cellular tyrosinase activities of oxyresveratrol: comparison with mulberroside A. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 27, 495–503. https://doi.org/10.3109/14756366.2011.598866 (2012).

Daneshmand, S. et al. Evaluation of the anti-melanogenic activity of nanostructured lipid carriers containing auraptene: A natural anti-oxidant agent. Nanomed. J. 9, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.22038/NMJ.2022.62354.1645 (2022).

Vaziri, M. S. et al. Preparation and characterization of undecylenoyl penylalanine loaded-nanostructure lipid carriers (NLCs) as a new α-MSH antagonist and antityrosinase agent. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 13, 290–300. https://doi.org/10.34172/apb.2023.036 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was advocated by the Chulalongkorn University–NSTDA Doctoral Scholarship and the 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Scholarship under the Ratchadapisek Somphot Endowment Fund. The authors would also like to extend our gratitude to the Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, and the National Nanotechnology Center (NANOTEC), National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA), Thailand, for their support in providing the facilities, equipment, and Fundamental Fund 2024 (P2351510).

Funding

The Graduate School, Chulalongkorn University, and The National Science and Technology Development Agency, National Nanotechnology Center, P2351510.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.M. conceptualized and designed the research, conducted all experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted as well as revised the manuscript. W.C. and M.K. conceptualized research, provided supervision, valuable guidance, resources, funding, and contributed to the manuscript revision. All authors have reviewed and approved the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mikled, P., Chavasiri, W. & Khongkow, M. Development of dihydrooxyresveratrol-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers for safe and effective treatment of hyperpigmentation. Sci Rep 14, 29211 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80671-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80671-0