Abstract

Quartz is one of the most abundant minerals in shales, occurring predominantly in three forms: biogenic quartz (BQ), detrital quartz (DQ) and clay-transformed quartz (CTQ). The content of quartz is typically correlated with the fracability of shale gas reservoirs. However, the origins of quartz and its influence on mechanical properties remain not fully elucidated. To address this gap, this study examines shale samples from LM1-LM8 graptolite zones in well W202 of the Weiyuan shale gas field, the Sichuan Basin as the research object. After systematic analysis of organic geochemistry, mineral composition, cathodoluminescence observation, major/trace elements, and log interpretation and calculation of shale mechanical parameters, the genetic mechanism of quartz was analyzed and the percentage of quartz of different origins and the influence on rock mechanical properties were evaluated quantitatively. The results indicate that the three types of quartz (BQ, DQ and CTQ) were variably present in the Longmaxi shale across different graptolite zones. The LM1-LM3 graptolite zones exhibit the highest abundance of BQ, with contents ranging from 58.3 to 79.6%, with an average of 65.7%. DQ predominates in the LM4-LM5 and LM6-LM8 graptolite zones, with average contents of 38.7% and 34.9%, respectively. The BQ content is marginally higher in the LM4-LM5 zone compared to the LM6-LM8 zone, averaging 12.7% and 6.1%, respectively. The three types of quartz exert a dual influence on Young’s modulus, and a single linear effect on Poisson’s ratio. An increase BQ content correlates with a decreased in Poisson’s ratio, whereas increased contents of DQ and CTQ correlate with an increased Poisson’s ratio. With the highest Young’s modulus and the lowest Poisson’s ratio, the LM1-LM3 shale is the most favorable interval for hydraulic fracturing. Furthermore, BQ is positively correlated with the Brittleness index (BI), whereas the contents of DQ and CTQ are negatively correlated with BI. When the quartz content falls between 52% and 85%, the ratio of DQ to BQ is optimal for fracture development coinciding with high BI values, which are most conducive to fracturing stimulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the low porosity and permeability, the industrial development of shale gas necessitates hydraulic fracturing. Assessing the fracability of shale is essential for pinpointing the “engineering sweet spots” within shale gas reservoirs. Quartz, one of the most abundant minerals in shale formations1, occurs in various forms, including BQ, DQ and CTQ. Despite the diversity of quartz types, the quartz content significantly influences the difficulty of fracturing, fracture geometry, and effectiveness of the fracturing process2. With the rapid development of shale gas industry, the research on shale has become increasingly in-depth and focused. Utilizing scanning electron microscope (SEM) and cathodoluminescence microscope (CL)3,4, the origins and the characteristics of quartz were extensively studied5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. The research reveals that, in addition to detrital quartz, authigenic quartz is associated with diagenetic processes within organic-rich shale. Authigenic quartz is formed as a result of various processes, including biogenic processes, transformation of clay minerals, hydrothermal silicon input and volcanic ash transformation. In the lower interval of Longmaxi Formation, the quartz is predominantly of biological origin, whereas in the upper interval, it primarily originates from terrestrial input. In the Niutitang Formation, quartz is locally of hydrothermal origin. These findings are substantiated by elemental composition, SEM-based monochromatic CL images5,13,16, biological assays13,17,18and quartz crystallinity index19. Furthermore, the correlations between origins of quartz and organic matter (OM) enrichment, storage capacity, fracability, and shale gas accumulation have been thoroughly examined. These studies reveal a strong correlation between various quartz types and the physical properties of rocks20,21,22,23 and they proposed that a holistic valuation of quartz types and their interaction with rock mechanical properties can’t rely solely on bulk geochemical or mineralogical analysis23. However, quantitative characterization of quartz from different sources and influence of various quartz origins on rock mechanical properties have received limited attention.

Specific types of graptolites can only inhabit in certain periods, providing a basis for high-precision stratigraphic subdivision and correlation. We follow the graptolite biozonation reported by24,25 and the graptolite zones in the Longmaxi Formation are referenced by their codes rather than stating the full names repeatedly. Shale samples from the LM1-LM8 graptolite zones in Well W202 of Weiyuan shale gas field were selected for X-ray diffraction, SEM observation, SEM-CL observation and elemental analysis. Through these analyses, the silica source of quartz was clarified and the percentage of quartz with different origins and the content variation in different biozonations were quantitatively characterized. Incorporating the dynamic Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio and BI derived from logging data, the impact of quartz types on rock mechanical properties was comprehensively evaluated. This paper demonstrated a feasible and reliable method for quantifying different types of quartz and established a quantitative relationship between quartz types and rock mechanical parameters, which can be applied to shed light on the unconventional reservoir characterization.

Geological setting

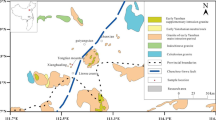

Through the systematic evaluation of the generation, enrichment and preservation conditions, the Longmaxi Formation and the Sichuan Basin has become the key strata and area for shale gas development26,27,28,29,30. The Weiyuan shale gas field is situated in the southwestern Sichuan Basin. Structurally, it is a part of the low paleo-fold belt in the Guzhong slope, in the southwest Sichuan Basin, and covers a production area of 1520 km231. The Silurian Longmaxi Formation was deposited in a deep-water shelf environment, and graptolite fossils are well preserved within it. Based on the lithological and logging data, the Silurian Longmaxi Formation is subdivided into Long1(S1l1) and Long 2 (S1l2) members, of which the Long1 member is well developed in the gas field with a thickness of 140 ~ 240 m and can further be divided into Long11 and Long 12 sub-members from bottom to top. Long11 sub-member consists of black carbonaceous shale with a thickness of 36 ~ 48 m32, which is rich in OM and well developed laminations. Long11 was divided into four intervals (S1l14, S1l13, S1l12 and S1l11) from top down. Through biostratigraphic analysis and correlation, it has been found that the high productive layer in the mid-lower S1l11mainly corresponds to the LM1-LM3 graptolite zones. The LM4-LM5 graptolite zones correspond to the upper part of the S1l11 and the S1l12 and the LM6-LM8 correspond to the S1l13 and the S1l14 in the Weiyuan area (Fig. 1).

Samples and experimental methods

Samples

A total of 23 shale samples were collected from 2535 m ~ 2575 m of well W202, mainly distributed in Long11 sub-member. Among them, 6 samples belong to the LM6-LM8 graptolite zones, 10 samples belong to LM4-LM5 graptolite zones, and 7 samples belong to the LM1-LM3 graptolite zones. X-ray diffraction, TOC, major/trace elemental analysis were carried out for all samples. Additionally, 12 samples were subjected to CL analysis and 7 samples were imaged by SEM.

TOC and mineral composition analysis

TOC measurement, mineral compositions analyses were completed in the National Energy Shale Gas R&D (Experiment) Center. TOC was measured by a LECO CS-230 carbon-sulfur analyzer in accordance with the standard GB/T 19,145 − 2003. Before the experiment, the samples were dried and grinded to 200 mesh. Then the following detailed procedures can be found in reference1.

Whole rock analysis and clay mineral composition were performed by using the German Bruker AXS D8 Discover X-ray diffractometer in accordance with the SY/T5163-2018 standard. Powdered samples with 200 mesh were prepared for experiments and the instrument parameters were set to 40 kV for voltage and 5 mA for current.

SEM and CL imaging techniques

The SEM observation was carried out using the FEI Helios650 dual-beam scanning electron microscope (FIB-SEM). The ultimate resolution of the SEM images reached 0.8 nm at 5 KV. Before scanning, the sample were first mechanically polished using successively grit and then milled by using a Gatan693 argon ion polisher at 4 kV and a low incident angle (7.5o) for 2 h. During SEM imaging, the SEM was operated in low vacuum mode at a working distance of about 10 mm and an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

The CL analysis was performed using the YF-2 cathodoluminescence instrument produced by the Instrument Factory of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The operating conditions for the probe were a voltage of 10 kV, a spot size of 5.5 nm, and a working distance of 5.0 ~ 6.5 mm.

Major/trace elemental analysis

The analysis of major and trace elements was conducted in the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology. The instrument used for major element analysis was X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF), following the standard GB/T14506.28-2010. The trace element concentrations were measured by the Perkin Elmer ELAN9000 inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS), following the standard GB/T14506.30-2010. Future details about the major and trace elements testing procedures can be found in reference33. The excess silica contents, which represents the SiO2 content above an average shale background, was calculated using the formula:34.

\(\:{Si}_{excess}\)=\(\:{Si}_{sample}-({Si/Al)}_{backgound}\times\:{Al}_{sample}\), the value of \(\:({Si/Al)}_{background}\) is 3.11

Results

TOC and mineral compositions

The TOC and mineral compositions of the shale samples are listed in Table 1. The TOC varies from 2.2 to 7.7%, averaging 4.5%, and exhibits a gradual increase from the top to the bottom. The mineral compositions are complex, including potassium feldspar, plagioclase, pyrite, quartz, dolomite, calcite, clay and quartz. Clay minerals and quartz are dominant minerals in shale samples. The clay content ranges from 0 to 36.7% %, with an average of 19.8%, and exhibits a gradual increase from the bottom to the top. The quartz content ranges from 16.5 to 91.8%, averaging 44.6%, and decreases gradually from the bottom to the top.

The mineral compositions exhibit minor variations in different graptolite zones. In the LM1-LM3 zone, quartz predominates with an average content of 82.8%. In LM4-LM5 zone, the clay and quartz contents are roughly equivalent, averaging 28.4% and 30.4%, respectively. In LM6-LM8 zone, clay content is marginally higher than quartz content, averaging 28.4% and 23.4%, respectively. K-feldspar has not been detected, possibly due to its low concentration which falls below the detection limit.

Clay minerals are primarily comprised of illite (3.0 ~ 29.1%, avg. 18.7%), which exhibits an upward increasing trend, chlorite (3.4 ~ 7.2%, avg. 4.9%) and a small amount of smectite (0 ~ 2.4%, avg. 0.5%).

Characteristics of major and trace elements

Major and trace elements are listed in Table 2. SiO2 is dominant, following by Al2O3, CaO and Fe2O3. The contents of SiO2, Al2O3, CaO and Fe2O3 are 40.14 ~ 86.37% (avg. 61.25%), 1.71 ~ 12.5% (avg. 8.33%), 1.52 ~ 16.84% (avg. 7.12%) and 0.46 ~ 7.08% (avg. 3.26%), respectively. The remaining oxides such as MgO, Na2O, K2O, MnO, TiO2, and P2O5 are all below 5%. For trace elements, the contents of Zr and Rb are 14.7 ~ 97.7 × 10−6 (avg. 48.8 × 10−6) and 17.2 ~ 140 × 10−6 (avg. 83.5 × 10−6).

Discussion

Origins of quartz

Detrital quartz

DQ is the product of weathering of parent rocks, transported into sedimentary basins by various geological forces. agents. The quartz grains in thin section display first-class interference color under plane-polarized light and exhibit wavy extinction under crossed-polarized light. The DQ was displayed in Fig. 2A and B, and DQ generally exhibits blue color under cathodoluminescence microscope (Fig. 2B). Authigenic quartz usually appears in the form of cryptocrystalline and microcrystalline aggregates under monochromatic polarized light (Fig. 2C and E). Authigenic quartz distributes no luminescence (Fig. 2D) or emits a dark brown light under cathodoluminescence microscope (Fig. 2F). The monochromatic CL spectra of detrital quartz usually exhibits two peaks, with a primary peak at 620 ~ 650 nm and a secondary peak at 420 ~ 450 nm13. The morphology and dimensions of detrital quartz grains are influenced by hydrodynamic conditions and transportation distance. Some quartz grains possess smooth edges, whereas others are angular. There are also a few quartz grains with bay-shaped edges, which may be the result of dissolution. Additionally, some individual quartz grains exhibit original sedimentary fractures on the surface16.

Zr and TiO2, associated with heavy minerals, serve as indicators of silty-grade terrigenous debris input10,35. In the LM1-LM3 and LM4-LM5 shales, SiO2 is negatively correlated with Zr and TiO2, suggesting a predominance of DQ. In contrast, for LM6-LM8 shales, SiO2 displays a positive correlation with Zr and TiO2, indicating a higher proportion of authigenic quartz (Fig. 3). It’s worth noting that when the shale samples from both LM1-LM3 and LM4-LM5 are combined together, the correlation coefficients between SiO2 content and Zr as well as TiO2 content increase significantly to 0.67 and 0.79, respectively, which indicates a continuity in the depositional environments of the LM1-LM3 and LM4-LM5. However, the LM4-LM5 shales have a significantly lower SiO2 content and remarkably higher Zr and TiO2 contents compared to LM1-LM3, which demonstrates a substantially higher content of debris-derived SiO2 in LM4-LM5 than in LM1-LM3.

Authigenic quartz

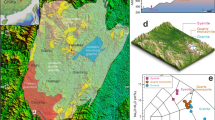

Authigenic quartz can form through diverse processes, including biological activity, hydrothermal activity, and transformation of clay minerals. The Al-Fe-Mn diagram effectively distinguishes siliceous rocks of hydrothermal origin from thoset of non-hydrothermal origin36,37. The LM1-LM8 shale samples are all distributed in non-hydrothermal origin area, suggesting SiO2 is not the product of hydrothermal activity (Fig. 4). The Rb-to-K2O ratio is commonly used as an indicator of sediment source38,39. A low ratio indicates abundant pyroclastic components, or an increased K content in the sediment. A high ratio suggests the sediment is primarily originated from weathered ancient parent rock40. The Rb, K2O values of the shale, bentonite and the Post-Archean Australian Average Shale (PAAS) samples were displayed in Fig. 5. The Rb/K2O ratio of the LM1-LM8 shale samples ranges from 0.038 to 0.045, which is higher than that of bentonite (0.026 ~ 0.042) and approximately equivalent to that of the PAAS (0.043). It suggests the Longmaxi shale is mainly originated from the upper crust. In addition, it was reported that the K2O-to-Na2O ratio of the bentonite in the Wufeng—Longmaxi Formations ranges from 15.54 to 27041. In comparison, the K2O-to-Na2O ratio of the 23 shale samples ranges from 1.42 to 4.53, with an average of 2.77, which is far lower than that of the bentonite, further confirming that the SiO2 in LM1-LM8 are not pyroclastic origin (Table 2). The ratio of TiO2 to Al2O3 can indicate the source of clay minerals. Usually, the ratio of TiO2/Al2O3 in acid volcanic ash is lower than 0.0240, and the value of the bentonite in Wufeng—Longmaxi Formations is below 0.02. The TiO2-to-Al2O3 ratios of the 23 samples are 0.04–0.05, higher than 0.02 (Table 2). It is concluded that the silica in the LM1-LM8 shale, Weiyuan shale gas field is not affected by volcanism.

Shale samples in different biozonations on Al-Fe-Mn discrimination diagram (base map after reference43).

Contents of K2O and Rb in different biozonations, K-bentonite and PAAS K-bentonite data sourced from reference44.

Biogenetic quartz

Two types of biogenetic silica have been identified through microscopic observation. One type exhibits biogenetic textures, while the other type lacks these textures. The quartz originated from siliceous organisms generally retains the original morphology (Fig. 2E and F). For example, radiolarian fossils appear as intact spherical structures filled with silica under microscopic observation (Fig. 2E). The quartz without biogenetic texture primarily forms through reprecipitation of dissolved silicon in the ocean, generally appearing as crypto-crystal and micro-crystal aggregates with vague surface, unclear boundaries and irregular shapes, or as fillings within fractures (Fig. 2B). This kind of quartz is non-luminescent and produces a broad luminescence peak at 620 ~ 650 nm in the CL spectra13. The ratio of Si to (Si + Fe + Al + Ca) is an important indicator of the silica source9,39,45. The ratio of BQ is generally greater than 0.8510,14. The ratio of the 23 samples ranges from 0.49 to 0.95, with an average of 0.70, and exhibits minor variation across different graptolite zones, with 0.83 ~ 0.95 (avg. 0.88) in LM1-LM3, 0.62 ~ 0.69 (avg. 0.66) in LM4-LM5 and 0.49 ~ 0.73 (avg. 0.56) in LM 6-LM8. The ratio shows that the authigenic quartz in LM1-LM3 is predominantly BQ, while the overlying LM4-LM8 contains a lesser amount of BQ.

Clay-transformed quartz

Clay-transformed quartz is mainly found in the interlayer pores of clay minerals (Fig. 6). Clay-transformed quartz is distributed in a granular form among clay minerals (Fig. 6A, C, D) and organic matter (Fig. 6B), with the quartz particles having a good degree of rounding. In Fig. 6B, in addition to the organic matter surrounding the quartz particles, filamentous clay minerals can also be found distributed near the quartz particles, which may suggest that these clay minerals were formed simultaneously with quartz through the transformation of smectite. The shale samples from the study area predominantly consist of illite, with minor amounts of chlorite and an absence of smectite, indicating that the Longmaxi Formation has entered the late stage of diagenesis. The diagenesis of clay minerals follows the sequence of smectite - illite/smectite mixed layer - illite, and kaolinite – illite46,47,48. Studies conducted previously suggest that the original clay minerals in the sedimentary basin were dominated by smectite46,48. However, subsequent differentiation and transformation of clay minerals driven by various diagenetic processes resulted in the absence of smectite in the collected samples. This indicates that the smectite has undergone a relatively complete transformation and the process can be described by the followed Eq14:

1.308[(Al3.15Mg0.85)(Si8.0)O20(OH)4(Na0.85)2H2 O(smectite)] + (0.06Fe2O3 + 0.56K2O + 0.02CaO)]=[(Al4.12Fe0.1Mg0.56)(Si7.17)O20(OH)4(K1.47Na0.01Ca0.03)](illite) + 3.29SiO2 + 0.56Na2O + 0.55MgO + 3.23H2O.

As shown by the equation, the transformation of smectite to illite requires the supply of K+, which mainly comes from K-feldspar dissolution. However, no K-feldspar was detected in the samples, probably because the K-feldspar has been dissolved completely. According to the equation, the shale with 777.75 g of illite can produce 197.4 g of SiO2. Therefore, the content of CTQ among the diagenetic quartz can be calculated from the illite content.

Quantitative characterization of quartz of different origins

As discussed previously, there are three types of quartz in the samples, including DQ, BQ and CTQ. The content of authigenic quartz (BQ and CTQ) can be calculated by using the excess silicon formula9 and the content of CTQ can be determined by the above equation. Then, the quartz content of each type can be derived respectively. The results are presented in Table 3. The excess silicon content in LM1-LM8 ranges from 2.9 to 37.5%, with an average of 14.9%, and the content of excess SiO2 is 6.13 ~ 80.3%, with an average of 31.8%. From LM1-LM3, LM4-LM5 to LM6-LM8, the content of excess SiO2 decreases progressively from 60.0 ~ 80.3% (avg. 67.1%), 11.3 ~ 36.7% (avg. 18.9%) to 6.13 ~ 33.63% (avg. 12.3%). It should be noted that only one sample in the LM6-LM8 interval shows a relatively high excess SiO2 content.

The contents of DQ, BQ and CTQ in S1l11 are 6.03 ~ 44.10% (avg. 29.40%), 0.21 ~ 79.6% (avg. 27.1%) and 0.76 ~ 7.4% (avg. 4.76%) respectively. Overall, the content of BQ decreases gradually, while the DQ content increases from the bottom to the top. Compared to BQ and DQ, the CTQ content is relatively low, with the minimum content at the bottom of Long11 and stabilizing at approximately 5% in the upper layers. Quartz of different types exhibits varying contents across different graptolite zones. LM1-LM3 is predominately BQ, with content ranging from 58.3 to 79.6%, 65.7% on average. In LM4-LM5, the contents of DQ and BQ are 23.0%~44.1% (avg. 38.7%) and 4.5 ~ 34.8% (avg. 12.7%), respectively. In LM6-LM8, the contents of DQ and BQ are 30.3 ~ 44.0% (avg. 34.9%) and 0.2%~27.6% (avg. 6.1%). Furthermore, the BQ content is positively correlated with both TOC and Ni + Cu/Al, and the correlation coefficient between BQ and Ni + Cu/Al is much higher, reaching 0.77 (Fig. 7), suggesting that paleo-productivity is a more reliable indicator of the silicon source.

Influence of quartz types on rock mechanical properties

Influence of quartz types on dynamic elastic parameters

It has been confirmed that shales with high Young’s modulus and low Poisson’s ratio are brittle and prone to the development of natural and induced fractures. Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio are crucial parameters for characterizing rock mechanical behavior. Usually, these parameters are obtained through rock mechanics experiments and geophysical methods. Rock static mechanical parameters are derived from applying a static stress on rock samples, whereas dynamic mechanical parameters are determined by continuously monitoring the P-wave and S-wave velocities propagating in the rock underground using geophysical techniques. Numerous studies have demonstrated that static and dynamic elastic parameters are linearly correlated6,49,50. Static Young’s modulus is approximately 70% of the dynamic Young’s modulus, and the dynamic Poisson’s ratio is basically equivalent to the static Poisson’s ratio51,52. Dynamic Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio can be derived from array acoustic logging data and the Eq. (1) (2) and (3) are as below:

where, \(\:{\mu\:}_{d}\) refers to dynamic Poisson’s ratio, dimensionless, G refers to shear modulus, GPa, Ed refers to dynamic Young’s modulus, GPa; \(\:{\rho\:}_{b}\) represents bulk density, g/cm3; \(\:\triangle{t}_{s}\,and\,\triangle{t}_{p}\) refer to S-wave and P-wave time differences, µs/ft (1ft = 0.3048 m).

The results of the calculated dynamic Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the LM1-LM8 shale samples are listed in Table 3. A comparative analysis of Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio among different biozonations was conducted and the results were illustrated in Fig. 8. In LM6-LM8, the Young’s modulus ranges from 25.8 to 34.1 GPa (avg. 30.8 GPa) and the Poisson’s ratio ranges from 0.17 to 0.21 (avg. 0.19). In LM4-LM5, the Young’s modulus is 26.4 ~ 36.2 GPa (avg. 30.9 GPa) and the Poisson’s ratio is 0.15 ~ 0.23 (avg. 0.19). In LM1-LM3, the Young’s modulus ranges from 30.0 to 36.0 GPa (avg. 33.2GPa) and the Poisson’s ratio ranges from 0.10 to 0.17 (avg. 0.13). Comparatively, the LM1-LM3 exhibits the highest Young’s modulus and the lowest Poisson’s ratio, rendering it the most favorable section for hydraulic fracturing. At present, LM1-LM3 is the primary target for shale gas exploration and development, and the industrial production confirms its superiority.

The relationships among quartz types and mechanical parameters (the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio) are displayed in Fig. 9, which shows that the quartz types are not merely linearly correlated with the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio. However, as the content of these three quartz types increases, the Young’s modulus also increases. Nonetheless, beyond a certain threshold, the Young’s modulus begins to decrease with further increase in quartz content. The content of quartz derived from clay minerals in the shale samples is low (0.76 ~ 7.39%, avg. 4.76%), accounting for less than 10% of the total SiO2 content. DQ and BQ constitute the primary components of quartz in shale. The correlation between quartz content and Young’s modulus reveals that the Young’s modulus reaches its maximum when the contents of DQ, BQ and CTQ are 22.8%, 46.4% and 3.7%, respectively, and then declines with the increasing quartz content. From Table 3, when the DQ is less than 22.8%, the content of plastic clay minerals is low, and biogenic microcrystalline quartz acts as the rock’s framework, leading to an increase in Young’s modulus. Conversely, when the DQ content exceeds 22.8%, BQ decreases significantly, whereas plastic clay minerals increase remarkably. Under these conditions, the incremental quartz does not alter the original microstructure of the rock, and the DQ floats in the shale matrix, resulting in a decrease in Young’s modulus. However, a higher BQ content is not always preferable. Numerous studies have demonstrated the beneficial role of BQ in pore network development, and shale samples with high BQ have higher OM content8,10,32. This implies that the content of mechanically “soft” OM and the porosity of the samples increase with the increasing content of BQ, leading to a decrease in the Young’s modulus. Other research also discovered an asymmetrical inverted “V” shaped relationship in P- wave velocity profile at a quartz content threshold of 41%51.

Poisson’s ratio exhibits a linear correlation with the contents of three types of quartz. The contents of CTQ and DQ are positively correlated with the Poisson’s ratio, with correlation coefficients of 0.45 and 0.58 respectively, whereas the content of BQ is negatively correlated with Poisson’s ratio, with a correlation coefficient of 0.64, indicating different types of quartz exert varying influence on the fracability of the shales. Consequently, the origins of quartz should be considered when assessing the brittleness of shale gas reservoir.

Influence of quartz types on rock brittleness

The brittleness index defined by elastic parameters (Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio) can be expressed by Eq. (4)52,54:

where BI refers to the rock brittleness index, dimensionless; Ed refers to normalized dynamic Young’s modulus, dimensionless; \(\:{\nu\:}_{d}\) refers to dynamic Poisson’s ratio, dimensionless,

The BI of the Longmaxi shale ranges from 48.3 to 74.2%, with an average of 60.8%. The middle-lower section of S1l11, corresponding to LM1-LM3, has the BI greater than 60%. As illustrated in Fig. 10, the different types of quartz are correlated linearly to the BI. As the BQ content increases, the BI shows an increasing trend with a correlation coefficient of 0.62. The contents of DQ and CTQ are negatively correlated to the BI, with correlation coefficients of 0.54 and 0.41, respectively. It further underscores that the influence of different types of quartz content on rock brittleness varies. Relying exclusively on quartz content to assess shale brittleness could result in inaccuracies.

Due to the low content of CTQ, the brittleness and fracture density of shale are mainly dependent on the contents of BQ and DQ. In comparison with pure BQ or DQ, an appropriate mixture of BQ and DQ can render the shale more brittle. A negative correlation between DQ and BQ contents has been observed in the Longmaxi shale. When the quartz content is below 52%, DQ predominates, and the shale exhibits a BI below 60% and reduced fracture density. When the quartz content exceeds 52%, BQ becomes predominant, resulting in an increased BI and fracture density. When the quartz content surpasses 85%, the BI begins to decrease concurrently with a reduction in fracture density (Fig. 11). Therefore, within the quartz content range of 52 ~ 85%, the ratio of DQ to BQ is optimal for fracture development.

In the marine Longmaxi Formation of the Sichuan Basin, apart from quartz as the predominant mineral, shale also contains significant amounts of clay minerals and carbonate minerals. These two types of minerals also have a significant impact on the brittleness of the shale. However, in the sweet spot layer of the Longmaxi Formation in Weiyuan, the quartz content exceeds 70%, whereas the content of clay minerals is so low that it is unable to be quantitatively detected. Consequently, this study mainly focuses on the impact of different types of quartz on the mechanical properties of rocks. Nonetheless, in other shale formations, clay and carbonate minerals should also be considered as the primary factors affecting the mechanical properties of rocks.

Conclusions

(1) Quartz is a predominant diagenetic mineral in shale, with silica exhibiting a variety of sources. The Longmaxi Formation primarily comprises biogenetic quartz, clay-transformed quartz and terrigenous detrital quartz.

(2) Different graptolite zones exhibit varying proportions of these three types of quartz. Biogenetic quartz dominates in the LM1-LM3 graptolite zones, with content ranging from 58.3 to 79.6%, and 65.7% on average. Detrital quartz predominates in LM4-LM6 and LM5-LM8, averaging 38.7%, 34.9%, respectively. LM4-LM5 has a higher content of biogenic quartz than LM6-LM8.

(3) Different types of quartz have different mechanical properties. Biological quartz positively affects the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio, whereas terrigenous detrital quartz and clay-transformed quartz are negatively correlated with the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio. The LM1-LM3 shales have the highest Young’s modulus and the lowest Poisson’s ratio, making them the most favorable target for fracturing stimulation.

(4) The content of biogenic quartz is positively correlated with the brittleness index, while the contents of clay-transformed quartz and detrital quartz are negatively associated with the brittleness index. For shales with a quartz content between 52% and 85%, the ratio of detrital quartz to biogenic quartz is optimal for engineering fracturing stimulation.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Change history

24 January 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article an incorrect email address for author Zhen Qiu was quoted. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to qiuzhen316@163.com.

References

Li, J. et al. Shale pore characteristics and their impact on the gas–bearing properties of the Longmaxi Formation in the Luzhou area. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 16896, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66759-7 (2024).

Zhao, P. et al. Study on Mineral composition and brittleness characteristics of shale gas reservoirs from the lower paleozoic in the Southern Sichuan Basin. Geoscience 28 (02), 396–403 (2014).

Schieber, J., Krinsley, D. & Riciputi, L. Diagenetic origin of quartz silt in mudstones and implications for silica cycling. Nature 406 (6799), 981–985. https://doi.org/10.1038/35023143 (2000).

Peltonen, C., Marcussen, Ø., Bjørlykke, K. & Jahren, J. Clay mineral diagenesis and quartz cementation in mudstones: the effects of smectite to illite reaction on rock properties. Mar. Petroleum Geol. 26, 887–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2008.01.021 (2009).

Guan, Q. Z. et al. Types of biogenic quartz and its coupling storage mechanism in organic-rich shales: a case study of the Upper Ordovician Wufeng formation to Lower Silurian Longmaxi formation in the Sichuan Basin, S W China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 48 (04), 1–10 (2021).

Wang, R. Y. et al. Brittleness evaluation of the Lower Cambrian Niutitang shale in the Upper Yangtze region: a case study in the Cengong block, Guizhou Province. Earth Sci. Front. 23 (1), 87–95 (2016).

Zhang, J. The Research of Quartz Source of Wufeng-Longmaxi Group in the Northeast of Sichuan Basin[D] Chengdu University of Technology, (2016).

Sun, C. X. et al. Quartz type and its control on shale gas enrichment and production: a case study of the Wufeng-Longmaxi formations in the Sichuan Basin and its surrounding areas, China. Earth Sci. 44 (11), 3692–3704 (2019).

Zhao, J., Jin, Z., Jin, Z., Wen, X. & Geng, Y. K. Origin of authigenic quartz in organic-rich shales of the Wufeng and Longmaxi Formations in the Sichuan Basin, South China: implications for pore evolution [J]. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 38, 21–38 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.11.037 (2017).

Guo, W. et al. Quartz genesis in organic-rich and its indicative significance to reservoir quality: a case study on the first submember of the first member of Lower Silurian Longmaxi formation in the southeastern Sichuan Basin and its periphery. Nat. Gas. Ind. 41 (02), 65–74 (2021).

Lu, L. F. et al. Biogenic origin and hydrocarbon significance of siliceous shale from the Wufeng-Longmaxi formations in Fuling area, southeastern Sichuan Basin. Petroleum Geol. Exp. 38 (04), 460–465 (2016).

Lu, L. F. et al. The origin of biogenic silica in siliceous shale from Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation in the Middle Yangtze region and its relationship with shale gas enrichment. Earth Sci. Front. 25 (04), 226–236 (2018).

Zhao, J., Jin, Z. J., Jin, Z. K., Wen, X. & Geng, Y. K. &Yan, C.N. The genesis of quartz in Wufeng-Longmaxi gas shales, Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Geoscience. 27 (02), 377–386 (2016).

Xi, Z. et al. Characterization of quartz in the Wufeng Formation in northwest Hunan Province, south China and its implications for reservoir quality [J]. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 179, 979–996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2019.04.051 (2019).

Milliken, K. L., Ergene, S. M. & Ozkan, A. Quartz types, authigenic and detrital, in the Upper Cretaceous Eagle Ford Formation, South Texas, USA [J]. Sed. Geol. 339, 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2016.03.012 (2016).

Zhou, Y. T. et al. Types and characteristics of quartz in shale gas reservoirs of the Longmaxi formation, Sichuan Basin, China. Acta Mineralogical Sinica. 40 (02), 127–136 (2020).

Qin, J. Z. et al. Characteristics of ultramicroscopic organic lithology of excellent marine shale in the upper Permian sequence, Sichuan Basin. Petroleum Geol. Exp. 32 (02), 164–170 (2010).

Liu, J. T., Li, Y. J., Zhang, Y. C., Liu, S. L. & Cai, Y. J. Evidences of biogenic silica of Wufeng-Longmaxi formation shale in Jiaoshiba area and its geological significance. J. China Univ. Petroleum. 41 (01), 34–41 (2017).

Liu, G. H., Zhai, G. Y., Yang, R. & He, T. P. Quartz crystallinity index: New quantitative evidence for biogenic silica of the late ordovician to early silurian organic-rich shale in the Sichuan Basin and adjacent areas, China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 64(5), 773–787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-020-9718-2 (2021).

Milliken, K. L., Olson, T. & Mountains, R. Silica diagenesis, porosity evolution, and mechanical behavior in siliceous mudstones, Mowry Shale (cretaceous), U.S.A. Journal of Sedimetary Research. 87, 366–387 (2017). https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2017.24

Peng, J. W., Milliken, K. L. & Fu, Q. L. Quartz types in the Upper Pennsylvanian organic-rich Cline Shale (Wolfcamp D), Midland Basin, Texas: implications for silica diagenesis, porosity evolution, and mechanical rock properties. Sedimentology 67, 2040–2064. https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12694 (2020).

Gao, P. et al. Effect of silica diagenesis on porosity evolution of deep gas shale reservoir of the lower paleozoic wufeng-Longmaxi formations, Sichuan Basin. Mar. Petroleum Geol. 145, 105873 (2022).

Peng, J. W., Hu, Z. Q. & Feng, D. J. Influence of quartz types on rock fabrics and bulk physical properties in organic-rich mudstone: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 249, 104670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104670 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Late ordovician to earliest silurian graptolite and brachiopod biozonation from the Yangtze region, South China, with a global correlation. Geol. Mag. 137 (6), 623–650 (2000).

Chen, X. et al. The global boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Hirnantian Stage (the uppermost of the Ordovician System). Episodes 29 (3), 183–196 (2006).

Fan, C. H., Li, H., Qin, Q. R., He, S. & Zhong, C. Geological conditions and exploration potential of shale gas reservoir in Wufeng and Longmaxi formation of southeastern Sichuan Basin, China. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 191, 107138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.107138 (2020).

Li, H., He, S., Radwan, A. E., Xie, J. T. & Qin, Q. R. Quantitative analysis of Pore Complexity in Lacustrine Organic-Rich Shale and comparison to Marine Shale: insights from experimental tests and Fractal Theory. Energy Fuels. 38, 16171–16188. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.4c03095 (2024).

Qiu, Z. et al. Revisiting paleoenvironmental changes on the Upper Yangtze Block during the ordovician-silurian transition: new insights from elemental geochemistry. Sed. Geol. 450, 106377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2023.106377 (2023).

Qiu, Z., Zou, C.N., Mills, B.J.W., Xiong, Y.J., Tao, H.F., Lu, B., Liu, H.L., Xiao, W.J., Poulton, S.W. A nutrient control on expanded anoxia and global cooling during the Late Ordovician mass extinction. Communications Earth & Environment. 3, 82. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00412-x (2022).

Wu, W., Cheng, P., Liu, S.Y., Luo, C., Gai, H.F., Gao, H.T., Zhou, Q., Li, T.F., Zhong, K.S., Tian, Hui. Gasin-Place (GIP) Variation and Main Controlling Factors for the Deep Wufeng-Longmaxi Shales in the Luzhou Area of the Southern Sichuan Basin, China. Journal of Earth Science. 34(4): 1002–1011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12583-021-1593-x (2023).

Ma, X. H. et al. Dominating factors on well productivity and development strategies optimization in Weiyuan Shale gas play, Sichuan Basin, S W China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 47 (03), 555–563 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Reservoir heterogeneity of the Longmaxi formation and its significance for shale gas enrichment. Energy Sci. Eng. 8 (12), 4229–4249. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.807 (2020).

Guo, Z. Post-collisional, potassic and ultrapotassic magmatism of the northern Tibetan Plateau: constraints on characteristics of the mantle source, geodynamic setting and uplift mechanisms. J. Petrol. 47 (6), 1177–1220. https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egl007 (2007).

Wedepohl, K. H. Environmental influences on the chemical composition of shales and clays. Phys. Chem. Earth. 8, 305–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/0079-1946(71)90020-6 (1971).

Wright, A. M., Spain, D. & Ratcliffe, K. T. Application of inorganic whole rock geochemistry to shale resource plays [C]. Canadian Unconventional Resources & International Petroleum Conference, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, 19–21, Oct. (2010).

Adachi, M., Yamamoto, K. & Sugisaki, R. Hydrothermal chert and associated siliceous rocks from the northern Pacific their geological significance as indication od ocean ridge activity. Sed. Geol. 47 (1–2), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(86)90075-8 (1986).

Yamamoto, K. Geochemical characteristics and depositional environments of cherts and associated rocks in the franciscan and Shi-Manto Terranes. Sed. Geol. 52 (1–2), 65–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-0738(87)90017-0 (1987).

Plank, T. & Langmuir, C. H. The chemical composition of subducting sediment and its consequences for the crust and mantle. Chem. Geol. 145 (3–4), 325–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-2541(97)00150-2 (1998).

Ran, B. et al. Origin of the Upper Ordovician–lower silurian cherts of the Yangtze block, South China, and their palaeogeographic significance. J. Asian Earth Sci. 108,1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2015.04.007 (2015).

McLennan, S. M., Taylor, S. R., McCulloch, M. T. & Maynard, J. B. Geochemical and Nd-Sr isotopic composition of deep sea turbidites: crustal evolution and plate tectonic associations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 54 (7), 2015–2050 (1990).

Lu, B. et al. The characteristics and geological significance of the K-bentonite in Wufeng Formation and Longmaxi Formation in Sichuan Basin and its peripheral areas. Chin. J. Geol. 52 (1), 186–202 (2017).

Zhang, J. M., Li, G. X. & Zhou, C. M. Geochemistry of light colour clayrock layers from the early Cambrian Meishucun stage in Eastern Yunnan and their geological significance. Acta Petrologica Sinica. 13 (1), 100–110 (1997).

Boström, K. The origin and fate of ferromanganoan active ridge sediments. Stockholm: Contributions in Geology 27(2),149–243 (1973).

Su, W. et al. K-bentonite, black-shale and flysch successions at the ordovician–silurian transition, South China: possible sedimentary responses to the accretion of Cathaysia to the Yangtze Block and its implications for the evolution of Gondwana [J]. Gondwana Res. 15 (1), 111–130 (2009).

Ruiz-Ortiz, P. A., Bustillo, M. A. & Molina, J. M. Radiolarite sequences of the Subbetic, Betic Cordillera, Southern Spain [J]. Springer New York. In: (eds Hein, J. R. & Obradovic, J.) Siliceous Deposits of the Tethys and Pacific Regions. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-3494-4_8 107–127(1989).

WANG, X. X. Characteristics of diagenesis and evolution of the clay minerals in cretaceous mudrock in Songliao Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 9 (1), 93–99 (1988).

Wang, X. P. et al. Study on clay minerals in the lower silurian Longmaxi formation in southern Sichuan Basin and its periphery. Nat. Gas Geoscience. 25 (11), 1781–1794 (2014).

Zhao, X. Y. & He, D. B. Clay minerals and shale gas. Xinjiang Petroleum Geol. 33 (06), 643–647 (2012).

Yin, S. et al. Characterization method of νp/νs and its relationship with rock physical parameters of continental tight sandstone and shale reservoir. Petroleum Geolgoy Recovery Effi. 22 (03), 22–28 (2015).

Wang, B. et al. The influence of rock composition on dynamic and static elastic properties of Longmaxi formation shales. Chin. J. Geophys. 62 (12), 4833–4845 (2019).

Shu, H. L. et al. A method for evaluating the geomechanical characteristics of shale gas: the geomechanical characteristics of the mountain shale in the intensively reworked marine area of South China. Nat. Gas. Ind. 41 (supplement1), 1–13 (2021).

Zhang, C. C., Wang, Y. M., Dong, D. Z., Li, X. J. & Guan, Q. Z. Evaluation of the Wufeng-Longmaxi shale brittleness and prediction of sweet spot layers in the Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas. Ind. 36 (09), 51–60 (2016).

Xu, Z. H. et al. Petrophysical properties of deep Longmaxi formation shales in the southern Sichuan Basin, S W China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 47 (06), 1100–1110 (2020).

Rickman, R., Mullen, M., Erik, P., Bill, G. & Donald, K. A practical use of shale petrophysics for stimulation design optimization: All shale plays are not clones of the Barnett shale. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition held in Denver, Colorado, USA, 21–24 September 2008 SPE 115258. https://doi.org/10.2118/115258-MS(2008).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.42222209) and the Scientific Research and Technological Development Programs of CNPC (No.2023ZZ0801, No.2021DJ2001,2024DJ8701).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z. and F.L. conceived of the whole project. Qun Zhao (Q.Z)., Z.Q., and W.L. wrote the initial version of the manuscript. W.L.K and W.L.G. analyzed the data and prepared the figures. X.Y.Z, G.Y.C and T.Q.Q. conducted the experimental analyses and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Liang, F., Zhao, Q. et al. Influence of quartz types on mechanical parameters in the early silurian Longmaxi shale, Sichuan Basin. Sci Rep 14, 29932 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80776-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80776-6