Abstract

Little is known about human polyomavirus 9 (HPyV9). The mode of transmission and the site of replication are unknown, and seroprevalence data have been published with a wide range. A total of 1038 serum samples from individuals aged 0.7–93 years were used for seroprevalence study. We observed that seropositivity increased with age among children and young adults, and a 36.2% adult seroprevalence was detected. The prevalence was examined in samples from the respiratory tract: cancerous and non-cancerous lung tissues, tonsils, adenoids, throat swabs, middle ear discharge and nasopharyngeal samples collected from children and adults. HPyV9 was detected in 5.2% of nasopharyngeal samples and 1% of tonsils. Upon a viral infection, the interaction of viral promoters and cellular factors may determine whether a virus productively replicates in a cell. The early and late promoter activity of HPyV9 and the effect of the large T antigen (LTAg) on it was investigated in respiratory, kidney, endothelial and colon cell lines, fibroblast and primary airway epithelial cells. The highest promoter activity was measured in A549 lung cell line. LTAg expression significantly increased the late promoter activity. Based on our results, the respiratory cells may be suitable for HPyV9 replication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

More than a decade after its discovery1, the clinical significance of human polyomavirus 9 (HPyV9) has remained unclear. Although DNA and seroprevalence studies started immediately, the answers to many fundamental questions remain unknown.

It is still unclear how frequent the HPyV9 infection is in the human population. According to seroprevalence studies, there is an increase in seroprevalence with age during childhood, and the adult seropositivity ranged between 11–47%2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. In addition to the large differences in the data, there was also a difference in how the positivity rates changed with age among adults. Nicol et al. reported that HPyV9 infections occurred throughout life, and that the seropositivity rate increased with age, reaching a maximum of 70% in individuals over 80 years of age3,4. Nevertheless, others published that adulthood seropositivity remained relatively stable or only moderately increased8,10,11, or it even declined with aging2,5,7.

The mode of transmission and the portal of entry for HPyV9 are still unknown. After the discovery of HPyV9 in the serum sample of an immunocompromised kidney transplant patient1, the viral DNA was detected with a low prevalence rate in blood1,6,13,14,15,16,17, urine1,16,17, respiratory samples16,17, lung autopsy tissue17, tonsils18, and skin samples17,19,20,21,22,23,24. At the same time, others did not observe HPyV9 DNA in blood25,26, urine26,27,28, respiratory samples19,26, tonsils29,30,31, cerebrospinal fluid26,32, feces26, or skin samples33,34. Entry of the virus into the body through the oral cavity, respiratory tract, or skin is only a hypothesis.

Immunosuppression and organ transplantation may increase the risk of HPyV9 infection. Compared with that in healthy blood donors, not only is HPyV9 viremia significantly greater after kidney transplantation6, but a significant increase in the HPyV9 seropositivity rate was also observed among the transplant patients compared with healthy control group6,35. However, it should be noted that HPyV9 was not detected in blood, urine, and respiratory swab samples from kidney transplant patients in another prospective, longitudinal study36. Similarly, the virus was not found in blood samples of allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients for one year post-transplant37. In a case series study, HPyV9 was the only pathogen detected in the widespread, hyperkeratotic skin lesions of three organ transplant patients who died from multiorgan failure one year after the onset of the skin eruptions. The virus was also detected in blood, urine, ocular and oral swabs, and lung autopsy samples from the patients, suggesting the spread and replication of HPyV917. Previously, we studied the presence of HPyV9 in blood, urine, and throat swab samples from pregnant women. The virus was detected in each specimen type, but we did not observe a higher prevalence during pregnancy compared to non-pregnant, healthy women16. Encoding for early, regulatory, tumour antigens makes all the polyomaviruses potentially oncogenic38. The association of HPyV9 with different tumours has been examined, but the viral DNA has not been detected in skin34,39,40,41, brain42, kidney, bladder43, tonsil31 or breast44 cancers.

The in vivo cell tropism of HPyV9 is unknown. In the absence of isolated virions, researchers have attempted to produce infectious viral particles by transfecting cells with complete HPyV9 genomes, but the experiments have failed9,13. Cell tropism is determined by receptor usage, the attachment of the viral capsid to the receptor on the host cell. Moreover, following entry, the steps of the replication within the nucleus are regulated by the non-coding control regions (NCCR) of the virus. The NCCR contains the origin of replication, and the bidirectional promoters and enhancers. Gene expression occurs from both strands: the early region encodes for regulatory large and small T antigens (LTAg and sTAg, and possibly other spliced variants) on one strand, whereas the viral capsid proteins are expressed from the late region on the other strand in the opposite direction. The interaction between NCCR, cellular transcription factors, and viral regulatory proteins determines gene expression and whether latency or productive viral replication occurs in a cell. Therefore, an in vitro study of the promoter activity in different cell types may help identify the possible permissive cells for HPyV938,45. For BK and JC polyomaviruses it has been proven that the viruses with rearrangements, deletions, and insertions in the NCCR sequence resulted in increased early gene expression, viral replication, and cytopathic effects46,47,48. Little is known about the genomic variability of HPyV9 detected, because only seven complete genomes have been deposited in GenBank. Interestingly, the NCCRs of four genomes had deletions, insertions and point mutations compared with that of the reference genome. The biological importance of the rearrangement in HPyV9 NCCR was studied by two research teams, who compared the promoter activities of the reference genome and the UF-1 isolate. However, owing to the differences in the materials and methods used, their results are only partially comparable49,50.

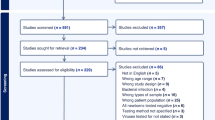

In the present study, our aim was to investigate the seroprevalence of HPyV9, and its differences across different age groups. In addition, we examined the prevalence of HPyV9 DNA in respiratory and middle ear samples, secondary lymphoid tissues, adenoids and tonsils, and cancerous and non-cancerous lung tissues. Our aim was to study whether the respiratory tract may be a portal of entry and/or a site for replication or persistent infection. Finally, we investigated the promoter activities of the reference genome and the UF-1 isolate in vitro in different human cells and the effects of LTAg on the early and late promoters. We used respiratory, kidney, endothelial and colon cell lines, a normal fibroblast and a primary airway epithelial cell. The aim of this project was to assess whether the transcription and replication of HPyV9 may take place in these cells.

2. Results and discussion

HPyV9 seroprevalence study

Using a VP1-based ELISA, we measured seroreactivity and then calculated the seroprevalence for the entire cohort, adults, and different age groups. The specificity of the antibody detection was tested by cross-reactivity experiments.

The seroresponsiveness of each serum sample to the HPyV9 VP1 antigen in age groups is shown in Fig. 1. A pairwise comparison of the OD values between age groups was performed using the Mann-Whitney test. A statistically significant difference was observed only between the 10–13 years and 14–20 years age groups (P = 0.0151). Multiple comparison test, Kruskal-Wallis Dunn’s post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in OD values between age groups, as indicated in Supplementary Table 1. The seroresponse increased significantly with increasing age among children.

To evaluate the specificity of the ELISA results and the antigenic cross-reactivity, ELISA measurements were carried out after pre-incubation of the serum samples with 2,000 ng of homologous or heterologous VP1 antigen at 37 °C for 1 h. VP1 proteins of Merkel cell PyV (MCPyV) and Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated PyV (TSPyV) were used as heterologous antigens, which were produced for our previous study51. The VP1 proteins of MCPyV and TSPyV share 59% and 62% amino acid identities with HPyV9 VP1, all of which belong to the Alphapolyomavirus genus. The results of this experiment are detailed in Table 1. Pre-incubation of the serum samples with the HPyV9 antigen resulted in a complete, statistically significant (P < 0.0001) decrease in the OD value; therefore, seronegativity in ELISA was observed. At the same time, pre-incubation of the serum samples with MCPyV or TSPyV antigens did not result in a change in the serostatus of the serum samples; the OD values of the samples did not change or changed only slightly. This finding is in agreement with the results of similar experiments from previous publications3,52, and others also did not detect evidence of strong cross-reaction based on the correlation analysis of the seroresponses against HPyV9, MCPyV and TSPyV5,7,8. Our results indicate that HPyV9-specific antibodies were detected in our ELISA measurements.

The overall seroprevalence was 30.6% for HPyV9, while the adult seropositivity was 36.2%, which, despite the differences in methods, is consistent with some previously published seroprevalence data3,4,6,7,9. Only Trusch et al. reported a higher, 47% adult seropositivity rate2, while others detected a markedly lower, 11–24% seroprevalence5,8,10,11,12. Figure 2 shows the age group specific seropositivity rates. Among the youngest children aged < 3 years, we did not detect antibodies against HPyV9. The antibody positivity rate increased significantly with increasing age (P < 0.0001, Χ2 test for trend) until the 21–39 year old group. The adult seroprevalence seemed to be relatively stable, with a slight decline over 80 years, which is in agreement with the observations of others5,7,11. Similar to the analysis of the seroreactivity, a significant increase in seroprevalence was observed between the 10–13 years and 14–20 years age groups (P = 0.0219; Fisher’s exact test). Despite the differences in seropositivity rates, Trush et al. observed a similar trend in seroprevalence by age groups2. An increase in the antibody positivity rate with increasing age among children was also reported by Nicol et al.53, but not by van der Meijden et al.5.

HPyV9 DNA prevalence study

We focused on respiratory samples during the DNA prevalence study. Although the mode of transmission for HPyV9 is still unknown, we cannot rule out the oral cavity or the respiratory tract as the site of entry. If it is hypothesized, the secondary lymphoid tissues may be the site for viral replication, even for persistence, and the virus may infect the lung.

Although high quality and quantity of DNA were isolated from each formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue Sect54, HPyV9 DNA was detected in neither cancerous nor non-cancerous lung tissue samples from study group 1. Mishra et al. detected HPyV9 DNA and mRNA by PCR and in situ hybridization in a lung autopsy sample, suggesting that the virus may replicate in this tissue17. However, no other study has confirmed this finding.

In study group 2, HPyV9 DNA was not detected in adenoid, throat swab or middle ear discharge samples, but it was detected in a tonsillar sample (1%, 1/100) from a 6 year old male patient. The complete viral genome from the tonsil was sequenced (GenBank accession number: MH844627). Kourieh et al. reported the same 1% DNA prevalence in tonsil brush samples18. Because others did not detect HPyV9 in tonsillar tissue specimens29,30,31, further studies are needed to clarify the role of these secondary lymphoid tissues in HPyV9 pathogenesis.

In study group 3, HPyV9 DNA was detected in 5.2% (48/919) of the nasopharyngeal samples. Following the real-time PCR, sequencing confirmed the presence of HPyV9 DNA in each real-time PCR positive sample. Each of the sequences was identical to the reference genome; therefore, these sequences were not deposited in GenBank. Table 2 shows the details of the data.

The HPyV9 DNA prevalence was significantly (P < 0.0001) higher among SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative patients (9.11%) than that among SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive patients (0.25%). Statistical analysis revealed that HPyV9 DNA positive patients (2.1–38.6 years, median: 27.1 years) were significantly (P = 0.0139) younger than HPyV9 negative patients (0.8–92 years; median: 33.9 years). HPyV9 prevalence was higher, 6.16% (40/649) in the adult population than that among children (2.96%, 8/270), but the difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.0508). No sex difference was detected between the HPyV9 DNA positive and negative patients. The HPyV9 prevalence that we observed in these nasopharyngeal specimens was higher than that we detected previously16, but the PCR methods were different. Notably, in 146 throat swab samples collected in 2016 and investigated in this study, we did not find HPyV9 DNA. The difference in sampling, throat swab sampling vs. nasopharyngeal swab sampling, cannot be the explanation for it because throat swab samples were HPyV9 DNA positive in our previous study16. In one study 2.2% of gargle samples collected from adults was positive for HPyV9 DNA18. Others did not detect the viral DNA in similar or other respiratory sample types, such as nasopharyngeal aspirates, throat and nose swabs, bronchial washing, bronchoalveolar lavage, and sputum samples obtained from patients with or without respiratory symptoms19,55. The nasopharyngeal samples used in our study were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, when there were restrictive measures and recommendations for social distancing and when schools and daycares were closed intermittently for weeks. Therefore, why we detected HPyV9 in nasopharyngeal samples with the highest prevalence to date is even more questionable. However, it suggests that the respiratory tract may be the site for HPyV9 entry. Further studies are needed to investigate the spread and replication site of HPyV9.

The relatively low prevalence rate and the failure to detect HPyV9 DNA can partially explain why little is known about the genetic divergence of the viral genome. An evolutionary analysis of all HPyV9 genomes available from GenBank was performed, and the results are shown in Fig. 3a. Haplotype network analysis is suitable for displaying the short term diversification of genomes. Network analysis was performed for the complete genomes (Fig. 3b) and the NCCR sequences (Fig. 3c), because the NCCR sequence presented the greatest variation in the genome. Both the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3a) and the haplotype network analysis (Fig. 3b and c) revealed four clusters of genomes. The European isolates formed one cluster. Based on the NCCR analysis (Fig. 3c), the reference sequence (refseq; GenBank accession number HQ696595.1), 915 F 06 001 PJ (GenBank accession number FR823284.2) and the M149 isolate (GenBank accession number MH844627.1) from this study belong to the same Hap1 haplotype. The USD14 (GenBank accession number MT416610.1) and USD16 (GenBank accession number MT416611.1) isolates are different haplotypes, Hap4 and Hap3, and form another cluster. The UF-1 (GenBank accession number KC831440.1) and USD19 (GenBank accession number MW139299.1) isolates are segregated clusters and haplotypes, Hap2 and Hap5 with the highest variation in the NCCR sequence.

Evolutionary analysis of HPyV9 genomes by the Maximum Likelihood method (panel a), haplotype network of HPyV9 genomes (panel b) and NCCR sequences (panel c). The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model64. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-7517.08) is shown. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Tamura-Nei model, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site (next to the branches). This analysis involved 7 nucleotide sequences. Codon positions included were 1st + 2nd + 3rd + Noncoding. There were a total of 5105 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X65, and TCS networks were developed by PopART66. In TCS network, the size of the circle representing a haplotype is relative to the number of sequences. Tables show the GenBank accession numbers of the sequences for each haplotype. NCCR: noncoding control region.

Except for the genome from this study, all the other HPyV9 genomes were isolated from immunocompromised patients, who had kidney or lung transplantation, Merkel cell carcinoma, or AIDS13,17. Immunosuppression can result in increased viral replication and therefore, higher mutation rates in the NCCR of BK polyomavirus. The rearranged NCCRs of the new variants may trigger viral replication46,56. The same can also be hypothesized for HPyV9. Therefore, it is important to collect and analyse more HPyV9 genome sequences.

In vitro study of HPyV9 promoter activity

The NCCR of polyomaviruses plays a key role in regulating viral gene expression and replication. This regulatory function of the promoters and enhancers is highly dependent on their sequence and their interaction with cellular and viral regulatory factors, such as transcription factors and viral regulatory proteins. Even if a cell is susceptible to a viral infection, its permissivity and the possibility of a productive viral infection are determined by these interactions. Functional analysis of the HPyV9 promoters in different cells may help to identify those cells in which the virus may replicate. The comparison of early and late promoter activities of NCCR variants may help in understanding the effects of mutations in regulatory sequences.

For these experiments, two isolates of HPyV9, the reference sequence, and UF-1 were used, as their NCCR sequences are significantly different and have been investigated by two other groups49,50,57. Based on our DNA prevalence study and the results of Mishra et al., it is hypothesized that the respiratory tract may be a replication site for HPyV9. Therefore, we chose primary airway epithelial cells, lung fibroblast MRC-5 cells, and lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. A549 and HEK-293 cells were used by others, which ensured the ability to compare the results. Moens et al. and Ajuh et al. performed their experiments in SW480, while we chose the Caco-2 cell line, which is also a colon adenocarcinoma cell line. We chose the endothelial cell line SK-HEP-1 because, during a viral spread, endothelial cells may play a role in dissemination.

First, we studied the promoter activities in different cells. Figure 4a shows the results. The luciferase activities of the four promoters (9_E, 9_L, UF-1_E and UF-1_L) in different cells were analysed statistically. The results are shown in Fig. 4b and e. We observed that both the early and late promoter activities of the two HPyV9 isolates were the strongest in the A549 lung carcinoma cell line and the weakest in the MRC-5 lung fibroblast line. The differences in the luciferase values of 9_E, 9_L, UF-1_E, and UF-1_L in these two cell types were 49-fold, 94-fold, 49-fold, and 242-fold, respectively. The results from embryonic kidney epithelial, HEK-293 cells, and colorectal adenocarcinoma epithelial, Caco-2 cells, did not show statistically different luciferase activities compared to the luciferase values in A549 cells. At the same time, in primary airway epithelial cells and liver adenocarcinoma endothelial cells, significantly weaker luciferase activities were measured for all four promoters.

Promoter activities of HPyV9 reference sequence and UF-1 isolate in different cells. Panel a shows the luciferase values of all four promoters in different cells. Luciferase values are shown separately for the HPyV9 early (panel b) and late promoters (panel c), and for the UF-1 isolate early (panel d) and late promoters (panel e). Each bar represents the mean of nine measurements with SDs from three independent experiments. 9_E: HPyV9 reference genome early promoter; 9_L: HPyV9 reference genome late promoter; UF-1_E: HPyV9 UF-1 isolate early promoter; UF-1_L: HPyV9 UF-1 isolate late promoter. A statistically significant difference is indicated by a red line with P value (Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test).

The results of the transfection experiments with the GFP expression vector revealed a difference in the transfection efficiency. It was assessed to be > 90% for HEK-293 and A549, > 70% for SK-HEP-1, ~ 60% for MRC-5, ~ 50% for primary airway epithelial, and ~ 30% for Caco-2 cells. The transfection efficiency may have had an effect on the luciferase activity. Therefore, to compare the different promoter activities, for each cell type, the 9_E promoter activity was set at 100%. The data are shown in Fig. 5. Compared with 9_L, the 9_E early promoter activity was significantly stronger in Caco-2, primary airway epithelial, SK-HEP-1 and MRC-5 cells, while in A549 cells the difference was not statistically significant. At the same time, in HEK-293 cells, 9_L late promoter activity was significantly higher than that of 9_E late promoter activity, and this observation is in agreement with previous publications49,50. The UF-1 early and late promoter activities did not differ in Caco-2 cells, while significantly stronger UF-1_L promoter activity was observed in A549, HEK-293, and SK-HEP-1 cells. Similar findings have been published for HEK-293 cells49,50. At the same time, in primary airway epithelial cells and MRC-5 fibroblasts, the UF-1_E promoter had significantly higher activity compared to UF-1_l promoter. Both the early and late promoter activities of UF-1 were higher in each cell type, except in HEK-293 cells, where the early promoter of UF-1 was significantly weaker than the early promoter activity of the reference sequence. In both previous studies, the reverse correlation was detected: the UF-1 early promoter activity was stronger49,50. Moens et al. detected relatively low early and late promoter activity in A549 cells, moderate activity in HEK-293 cells, and the highest one in SW480 cells57. Comparing the relative luciferase activities, we measured much higher values for A549 and HEK-293 cells. Ajuh et al. also detected the highest promoter activity in SW480 cells50. Although the difference was not statistically significant, we measured lower activities in Caco-2 cells for all four promoters. The transfection efficiency of HEK-293 cells was comparable to that we detected, but Moens et al. observed much lower efficiency in A549 cells than we did57. Both Caco-2 and SW480 are colon adenocarcinoma cells, but there are differences in their morphology58 and we observed a lower transfection efficiency for Caco-2 cells than that was published for SW480 cells57. The method we use is only partially similar to that used by the two research teams. Although Ajuh et al. used a bidirectional reporter vector, they studied the expression of fluorescent proteins 48 h after transfection50. Moens and colleagues used a luciferase expression vector, but it was a unidirectional reporter vector, meaning that late and early promoter activities were studied separately57. These differences in the methods may explain some discrepancies between the results.

Relative early and late promoter activities of HPyV9 reference sequence and UF-1 isolate in different cells. Each bar represents the mean of nine measurements with SD from three independent experiments. 9_E: HPyV9 reference genome early promoter; 9_L: HPyV9 reference genome late promoter; UF-1_E: HPyV9 UF-1 isolate early promoter; UF-1_L: HPyV9 UF-1 isolate late promoter. The 9_E promoter activity was set as 100%. A statistically significant difference is indicated by a red line a red line with P value (Wilcoxon t-test, two-tailed).

The differences in promoter activities that we observed in different cells could serve as a good basis for determining which cell types may be involved in HPyV9 replication. Although we observed low activity of the promoters in primary airway epithelial cells, the highest activity was detected in A549 lung cells. There is strong evidence for the replication of HPyV9 in the lung17, and on the basis of the DNA prevalence data from this study, the respiratory tract may be at least a portal of entry for the virus.

The putative binding sites for LTAg do not differ between the NCCR of UF-1 and the HPyV9 reference sequence49. However, LTAg of polyomaviruses can interact not only directly with the promoters but also via interactions with cellular transcription factors59. To study the effect of regulatory LTAg on the promoters, luciferase activities were measured in cells co-transfected with LTAg expression and luciferase reporter vectors. Because differences in transfection efficiency may have affected these experiments, only HEK-293, A549, SK-HEP-1, and primary cells were studied. Western blotting was used to confirm the expression of LTAg (Supplementary Fig. 1).

During the co-transfection experiments, when the reporter vector and empty pcDNA3.1(+) were used together, we observed decreased luciferase activity compared with the luciferase activity measured in cells transfected with the reporter vector alone. The possible competition between the HPyV9 promoter and the CMV promoter of the pcDNA3.1(+) vector may be responsible for this phenomenon. Notably, the strongest effect of co-transfection on luciferase activity was observed for primary airway epithelial cells, whereas the smallest effect of the empty pcDNA3.1(+) vector was detected in SK-HEP-1 cells.

The effects of LTAg on promoter activity are shown in Fig. 6. In our experiments, LTAg expression resulted in a significant increase in both 9_L and UF-1_L late promoter activity in each cell type. The fold changes in 9_L and UF-1_L promoter activities were comparable in A549, 293 and primary airway epithelial cells, and there was no marked difference among the cells. The strongest increase in luciferase activity was observed in SK-HEP-1 cells, and the late promoter activity of UF-1 showed a much greater increase than that of the reference HPyV9. These results are in agreement with the function of LTAg, since LTAg not only promotes viral DNA replication but also transactivates the late genes38.

Effect of LTAg on promoter activities of HPyV9 reference sequence and UF-1 isolate in different cells. Each bar represents the mean of nine measurements with SDs from three independent experiments. 9_E: HPyV9 reference genome early promoter; 9_L: HPyV9 reference genome late promoter; UF-1_E: HPyV9 UF-1 isolate early promoter; UF-1_L: HPyV9 UF-1 isolate late promoter. A statistically significant difference is indicated by a red line a red line with P value (t-test, two-tailed). LTAg: large T antigen. In the tables, the fold changes in promoter activity are presented as the means (min–max).

In each cell type, the 9_E early promoter activity was decreased by the LTAg, and this decrease was statistically significant in all cells, except the primary airway epithelial cells. The moderate fold changes were very similar in different cells. UF-1_E promoter activity did not change significantly in response to LTAg in A549 and HEK-293 cells; however, a significant increase was detected in SK-HEP-1 cells and a significant decrease was detected in primary airway epithelial cells.

In a previous study, compared to our observation, the effect of LTAg expression on promoter activities was different in HEK-293 cells. They detected a reverse effect on the promoter activities of HPyV9 reference sequence: a significant increase in early promoter activity and a significant decrease in late promoter activity. Similarly to us, they also observed a significant increase in late promoter activity of UF-1, but the LTAg also resulted in a significant increase in UF-1 early promoter activity49. All this draws attention to the fact that, owing to methodological differences, different results may be obtained for similar experiments. Therefore, the most important limitation of our in vitro study is that our results are only partially comparable to previous results.

In conclusion, we observed a 36.2% adult HPyV9 seropositivity rate. The seroprevalence increased with age during childhood and in young adults, but the positivity rate was relatively stable among adults. We detected HPyV9 DNA in 5.2% of nasopharyngeal samples and in 1% of tonsils, but not in adenoid, cancerous, or non-cancerous lung tissues. We sequenced a complete HPyV9 genome and performed evolutionary analysis. Those genomes that harboured rearranged NCCRs formed distinct haplotypes. On the basis of our data and a case series study, we hypothesized that the respiratory tract may be at least the portal of entry for HPyV9. We performed functional analysis of the NCCR in lung A549, primary airway epithelial, lung fibroblast, endothelial, and HEK-293 kidney epithelial cells. Two distinct NCCR haplotypes were compared, and the effect of the HPyV9 LTAg expression on the promoters was examined. The promoters of UF-1 isolate showed stronger activities in all cells, except the early promoter in HEK-293 cells. We detected that LTAg expression resulted in a significant increase in late promoter activity. Our findings suggest that A549 lung and HEK-293 kidney epithelial cells may be suitable for HPyV9 replication. We concluded that respiratory cells and different HPyV9 haplotypes should be studied further.

Materials and methods

The seroprevalence study was performed with the approval of the Regional and Institutional Research Ethics Committee, Clinical Centre, University of Debrecen, Hungary (DE RKEB/IKEB: 5134 − 2018). For DNA prevalence study sample collection and analysis were approved by the National Public Health and Medical Officer Service (number: IF-5418-7/2016), the National Scientific and Ethical Committee of Hungary (ETT TUKEB, 651-3/2016/EKU; 0027/16) and the Regional and Institutional Research Ethics Committee, Clinical Centre, University of Debrecen (DERKEB/IKEB: 5770 − 2021 and IX-R-052/00016–29/2012). All methods were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients and or their legal guardian. The samples were analysed anonymously.

HPyV9 seroprevalence study

Serum samples

A total of 1038 serum samples from 320 children (< 18 years) and 718 adults were analysed for the presence of antibodies against HPyV9 VP1 antigen. Serum samples were sent to Medical Microbiology, University of Debrecen, for diagnostic serology tests. Samples were selected from those patients who did not receive blood products within one year, did not receive immunosuppressive treatment, or had no altered immune system function due to an underlying disease. The study group included 520 females and 518 males. The age groups of the samples and patient data are detailed in Table 3.

ELISA

The IgG antibodies against the HPyV9 VP1 antigens were detected using an in-house, indirect ELISA. The codon optimized VP1 major capsid protein encoding gene of the reference HPyV9 genome (GenBank: HQ696595.1) was expressed in Origami B(DE3)pLacI competent cells (Novagen, Pretoria, South Africa, Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA), then purified from the cytoplasmic lysate and analysed as detailed previously51,60. The protocol was the same as we detailed in our previous publications; 50 ng of antigens were coated in each well51,61. All the serum samples were analysed in duplicate, and the OD value of each sample was calculated as the mean after the OD value of the blank was subtracted. The same method was used to determine the cut-off value for positivity, as described in our previous publications51. The seropositivity of a sample was considered if the OD value of the sample was > 0.343.

HPyV9 DNA prevalence study

Samples

Table 4 summarizes the samples and patient data used for the DNA prevalence study. In study group 1, a total of 147 lung tissue samples from 143 patients were included, out of which 100 were lung carcinoma samples and 47 were non-cancerous tissues. Control tissue samples were obtained from patients with pneumonia, fibrosis or emphysema. These tissue samples were sent to the Department of Pathology at the University of Debrecen for diagnosis between 2012 and 2016, and we used these samples in our previously published study54. Nucleic acid extraction from the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections and the control PCR of the isolated nucleic acid were performed as described previously54.

In study group 2, 100 adenoid and 100 tonsillar tissue samples, 146 throat swabs, and 15 middle ear discharge samples were collected from 146 patients in 2016. Nucleic acid was extracted directly after the collection, after which it was controlled, as we described in our previous publication62.

In study group 3, 919 nasopharyngeal samples were included. Samples were sent for SARS-CoV-2 PCR diagnosis to Medical Microbiology, University of Debrecen, between 2020 and 2022, and 403 samples were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The isolation of nucleic acids was the same as we described previously60.

To control nucleic acid isolation and amplification, human β-globin DNA was detected from the nucleic acid as we detailed previously43. Additionally, during SARS-CoV-2 PCR an RNA internal control was also amplified and detected according to the manufacturers’ instruction60.

HPyV9 real-time PCR

HPyV9 real-time PCR was carried out in a final volume of 25 µL using 2X TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), amplifying 500 ng nucleic acid template from tissues or 10 µL template from other samples. The reaction mixture contained 500 nM and 500 nM primers (HPyV9_VP1_qF: 5’CCAAAACTGGAGAGGCCTACCT3’ and HPyV9_VP1_qR: 5’ TTGAGGCATAAGACCAGAGAACAAG 3’) and 200 nM probe (HPyV9_Vp1_probe: 5’ VIC-TAATGTAACTCTAAGGAAACGGGTT-MGB). Primers and probe were designed for the VP1 region of the HPyV9 genome. The PCR protocol was set according to the instructions of the master mix. The HPyV9 VP1 sequence (GenBank: HQ696595.1) was synthesized (GeneArt Gene Synthesis, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and cloned into pJET1.2/blunt vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and used as a positive control in real-time PCR. The limit of detection was 5 copies/PCR.

Sequencing

To verify the real-time PCR results, primers were designed to amplify and sequence a partial sequence of the large T antigen coding region. The PCR reaction mix contained 1U Phusion Hot Start II High Fidelity DNA Polymerase in HF buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 500 nM forward (9szLT-F2: 5’TTTTGAAAAACATCCCATGAG3’) and 500 nM reverse (9szLT-R3: 5’CCCCCTTTTAAGTTGTTG3’) primers. The PCR started with denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 56 °C for 15 s, and an extension at 72 °C for 15 s, then finalized by an extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR product was purified after separation on a 1% agarose gel using gel electrophoresis. The entire genome was amplified using primer walking method. The sequences of the primers are detailed in Supplementary Table S2. Sequencing was carried out using BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit and ABI PRISM 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sequence alignment was performed with AliView software.

In vitro study of HPyV9 promoter activity

The early and late promoter activity of HPyV9 and the effect of the LT antigen on it were studied in vitro using a bidirectional luciferase reporter vector.

Vectors for transfection

The complete NCCRs of the reference HPyV9 genome (GenBank: HQ696595.1) and the UF-1 isolate (GenBank: KC831440.1) were commercially synthesized (GeneArt Gene Synthesis) and inserted into the pGL4Luc-RLuc vector (Addgene Inc., Watertown, MA, USA), a bidirectional reporter vector encoding for firefly and Renilla luciferase in different directions63. Henceforth, the reference genome is referred to as 9, whereas the UF-1 isolate is UF-1. The large T antigen encoding gene of HPyV9 was also synthesized with a C-terminal HA tag coding sequence and was subsequently inserted into a pcDNA 3.1(+) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) plasmid. The plasmids were amplified in XL1-Blue Supercompetent Cells (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and then purified using the PureLink Expi Endotoxin-Free Maxi Plasmid Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plasmid constructs were confirmed by sequencing. To investigate the transfection efficiency, the pmaxGFP (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) vector was used. To monitor the transfection efficiency, the expression of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) was detected using Axiovert 40 CFL microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany).

Cell cultures

Normal, human primary small airway epithelial cells were maintained in Airway Cell Basal Medium supplemented with Bronchial Epithelial Growth Kit (ATCC, LGC Standards GmbH, Wesel, Germany). A549 cells (human lung carcinoma epithelial cells, ATCC) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (cat. No.: 16140071) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco Inc., Thermo Fisher Scientific). HEK-293 cells (human, embryonal, kidney epithelial cells, ATCC), Caco-2 cells (human epithelial cells from colorectal adenocarcinoma, ATCC), MRC-5 cells (normal, human lung fibroblast cells, ATCC), and SK-HEP1 (human endothelial cells from liver adenocarcinoma, ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (D-MEM, cat. No.: 31885023, Gibco) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin solution. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Transfection

The cells were seeded into a 12-well plate (TPP Techno Plastic Products AG, Trasadingen, Switzerland) 24 h before the transient transfection. Transfection was carried out when the confluence reached 90% for the primary cells and 70–80% for the other cells. Before the transfection, the cell culture medium was replaced with Opti-MEM medium (Gibco) after washing the cells twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). The cells were transfected with 1 µg of the bidirectional luciferase reporter vector using Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 3 µL of Lipofectamine 2000 reagent was mixed in 100 µL of Opti-MEM medium and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 5 min. After the incubation, the mixture was mixed with 100 µL of Opti-MEM medium containing 1 µg of plasmid (pGL4Luc-RLuc vector with or without HPyV9 NCCR), incubated at RT for 20 min, and then the mixture was added to the cell. After six hours of incubation, the transfection medium was replaced with the normal maintenance medium of the cells. Mock transfection was performed in the same way as described, except that the transfection did not contain any vectors. When the effect of the LT antigen on the promoter activity was studied, co-transfection was carried with 200 ng of pcDNA3.1(+) containing or not containing the LT antigen sequence in the transfection mixture.

Dual luciferase assay

The promoter activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter (DLR) Assay Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). The cells were lysed in 200 µL of 1X passive lysis buffer using a cell scraper after being washed twice with PBS. The firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using the DLR kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In our experiments, firefly luciferase activity represented the late promoter activity (L), while Renilla luciferase activity was the marker for the early promoter activity (E). The luciferase activity of a cell sample from a well was normalized relative to the protein concentration of the cells from the well. The Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to measure the protein concentration according to the instructions.

Western blotting of LT antigen

Proteins of the whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and then blotted on a PVDF (polyvinylidene difluoride) membrane (Merck) with a 0.45-µm pore size. The membrane was blocked for 1 h in 1X Pierce Clear Milk blocking buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), then incubated for 16 h at 4 °C with the primary antibody 1:10,000 diluted in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST). To detect the HA-tagged LT antigens, HA Tag Monoclonal Antibody (cat. No.: 26183, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used, while beta-actin was labeled with beta Actin Loading Control Monoclonal Antibody (BA3R) (cat. No.: MA5-15739, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The membrane was washed three times with TBST, and then HRP-conjugated goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) superclonal recombinant secondary antibody (cat. No.: A28177, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added in a 1:20,000 dilution in blocking buffer, and it was incubated at RT for 1 h. Following three cycles of washing with TBST, the proteins were detected with Immobilon ECL Ultra Western HRP Substrate (Merck) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test for trend, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, and t-test were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.4.0. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.005. Mega X software was used for phylogenetic analysis, and PopART software was used to develop haplotype networks.

Data availability

The viral genome sequence generated during the current study is available in the GenBank with accession number: MH844627. All other sequences used for analyses are available in the GenBank repository (accession numbers: HQ696595.1; MH844627.1; FR823284.2; KC831440.1; MT416611.1; MT416610.1; MW139299.1).

References

Scuda, N. et al. A novel human polyomavirus closely related to the African green monkey-derived lymphotropic polyomavirus. J. Virol. 85, 4586–4590 (2011).

Trusch, F. et al. Seroprevalence of human polyomavirus 9 and cross-reactivity to African green monkey-derived lymphotropic polyomavirus. J. Gen. Virol. 93, 698–705. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.039156-0 (2012).

Nicol, J. T. et al. Seroprevalence and cross-reactivity of human polyomavirus 9. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18, 1329–1332 (2012).

Nicol, J. T. J. et al. Age-specific seroprevalences of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus, Human polyomaviruses 6, 7, and 9, and Trichodysplasia Spinulosa-Associated Polyomavirus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 20, 363–368. https://doi.org/10.1128/Cvi.00438-12 (2013).

van der Meijden, E. et al. Different serologic behavior of MCPyV, TSPyV, HPyV6, HPyV7 and HPyV9 polyomaviruses found on the skin. PloS One. 8, e81078 (2013).

van der Meijden, E. et al. Human polyomavirus 9 infection in kidney transplant patients. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 991–999. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2006.140055 (2014).

Sroller, V. et al. Seroprevalence rates of HPyV6, HPyV7, TSPyV, HPyV9, MWPyV and KIPyV polyomaviruses among the healthy blood donors. J. Med. Virol. 88, 1254–1261 (2016).

Gossai, A. et al. Seroepidemiology of human polyomaviruses in a US Population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 183, 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv155 (2016).

Korup-Schulz, S. V., Lucke, C., Moens, U., Schmuck, R. & Ehlers, B. Large T antigen variants of human polyomaviruses 9 and 12 and seroreactivity against their N terminus. J. Gen. Virol. 98, 704–714. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.000714 (2017).

Antonsson, A. et al. Prevalence and stability of antibodies to thirteen polyomaviruses and association with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a population-based study. J. Clin. Virology: Official Publication Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 101, 34–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2018.01.013 (2018).

Kamminga, S., van der Meijden, E., Feltkamp, M. C. W. & Zaaijer, H. L. Seroprevalence of fourteen human polyomaviruses determined in blood donors. PloS One. 13, e0206273. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206273 (2018).

van Rijn, A. L. et al. Impact of HPyV9 and TSPyV coinfection on the development of BK Polyomavirus viremia and associated nephropathy after kidney transplantation. J. Med. Virol. 91, 1142–1147. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25397 (2019).

Lednicky, J. A., Butel, J. S., Luetke, M. C. & Loeb, J. C. Complete genomic sequence of a new human polyomavirus 9 strain with an altered noncoding control region. Virus Genes. 49, 490–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11262-014-1119-z (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Multiplex analysis of human polyomavirus diversity in kidney transplant recipients with BK virus replication. J. Clin. Virology: Official Publication Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 120, 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2019.08.012 (2019).

Kamminga, S., van der Meijden, E., de Brouwer, C., Feltkamp, M. & Zaaijer, H. Prevalence of DNA of fourteen human polyomaviruses determined in blood donors. Transfusion 59, 3689–3697. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.15557 (2019).

Csoma, E., Sapy, T., Meszaros, B. & Gergely, L. Novel human polyomaviruses in pregnancy: higher prevalence of BKPyV, but no WUPyV, KIPyV and HPyV9. J. Clin. Virology: Official Publication Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 55, 262–265 (2012).

Mishra, N. et al. Human polyomavirus 9-An Emerging Cutaneous and Pulmonary Pathogen in Solid Organ Transplant recipients. JAMA Dermatology. 158, 293–298. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5853 (2022).

Kourieh, A. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of human polyomavirus infections in non-malignant tonsils and gargles: the SPLIT study. J. Gen. Virol. 99, 1686–1698. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.001156 (2018).

Sauvage, V. et al. Human polyomavirus related to African green monkey lymphotropic polyomavirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 1364–1370 (2011).

Hampras, S. S. et al. Natural history of polyomaviruses in men: the HPV infection in men (HIM) study. J. Infect. Dis. 211, 1437–1446. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiu626 (2015).

Purdie, K. J. et al. The role of human papillomaviruses and polyomaviruses in BRAF-Inhibitor Induced Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and Benign Squamoproliferative lesions. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1806. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01806 (2018).

Bopp, L. et al. Natural history of Cutaneous Human Polyomavirus infection in healthy individuals. Front. Microbiol. 12, 740947. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.740947 (2021).

Dona, M. G. et al. Prevalence of 13 polyomaviruses in actinic keratosis and matched healthy skin samples of immunocompetent individuals. Infect. Agents cancer. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-022-00472-w (2022).

Wieland, U. et al. Human polyomaviruses 6, 7, 9, 10 and trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus in HIV-infected men. J. Gen. Virol. 95, 928–932 (2014).

Imajoh, M., Hashida, Y., Taniguchi, A., Kamioka, M. & Daibata, M. Novel human polyomaviruses, Merkel cell polyomavirus and human polyomavirus 9, in Japanese chronic lymphocytic leukemia cases. J. Hematol. Oncol. 5, 25 (2012).

Rockett, R. J. et al. Detection of novel polyomaviruses, TSPyV, HPyV6, HPyV7, HPyV9 and MWPyV in feces, urine, blood, respiratory swabs and cerebrospinal fluid. PloS One. 8, e62764 (2013).

Franzen, J. et al. Studies of human polyomaviruses, with HPyV7, BKPyV, and JCPyV present in urine of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplanted patients with or without hemorrhagic cystitis. Transpl. Infect. Disease: Official J. Transplantation Soc. 18, 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.12500 (2016).

Dolci, M. et al. Particulate matter exposure increases JC Polyomavirus replication in the human host. Environ. Pollut. 241, 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.044 (2018).

Sadeghi, M. et al. Multiplex detection in tonsillar tissue of all known human polyomaviruses. BMC Infect. Dis. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2479-5 (2017).

Peng, J., Li, K., Zhang, C. & Jin, Q. MW polyomavirus and STL Polyomavirus present in tonsillar tissues from children with chronic tonsillar disease. Clin. Microbiol. Infection: Official Publication Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 22, 97e91–97e93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.08.028 (2016).

Herberhold, S. et al. Human polyomavirus and human papillomavirus prevalence and viral load in non-malignant tonsillar tissue and tonsillar carcinoma. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 206, 93–103. 1007/s00430-016-0486-6 (2017). [pii].

Delbue, S. et al. Human polyomaviruses in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of neurological patients. Microorganisms 8 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8010016 (2019).

Wieland, U. et al. Human polyomaviruses 6, 7, 9, 10 and trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus in HIV-infected men. J. Gen. Virol. 95, 928–932. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.061259-0 (2014).

Bergallo, M. et al. DNA from human polyomaviruses, MWPyV, HPyV6, HPyV7, HPyV9 and HPyV12 in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Anticancer Res. 38, 4111–4114. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.12701 (2018).

Kamminga, S. et al. JC and Human polyomavirus 9 after kidney transplantation: an exploratory serological cohort study. J. Clin. Virology: Official Publication Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 143, 104944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104944 (2021).

Bialasiewicz, S. et al. Detection of recently discovered human polyomaviruses in a longitudinal kidney transplant cohort. Am. J. Transplant. 16, 2734–2740. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13799 (2016).

Zanella, M. C. et al. Longitudinal detection of twenty DNA and RNA viruses in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients plasma. Viruses 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/v15040928 (2023).

Moens, U. et al. Biology, evolution, and medical importance of polyomaviruses: an update. Infect. Genet. Evol. 54, 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2017.06.011 (2017). doi:S1567-1348(17)30198-3 [pii].

Scola, N. et al. Prevalence of human polyomaviruses in common and rare types of non-merkel cell carcinoma skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 167, 1315–1320 (2012).

Ramqvist, T., Nordfors, C., Dalianis, T. & Ragnarsson-Olding, B. DNA from human polyomaviruses, TSPyV, MWPyV, HPyV6, 7 and 9 was not detected in primary mucosal melanomas. Anticancer Res. 34, 639–643 (2014).

Schrama, D. et al. Presence of human polyomavirus 6 in mutation-specific BRAF inhibitor-induced epithelial proliferations. JAMA Dermatology. 150, 1180–1186. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1116 (2014).

Hashida, Y. et al. Prevalence of human cytomegalovirus, polyomaviruses, and oncogenic viruses in glioblastoma among Japanese subjects. Infect. Agents cancer. 10 https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-9378-10-3 (2015).

Csoma, E., Bidiga, L., Mehes, G. & Gergely, L. No evidence of human polyomavirus 9, WU and KI DNA in kidney and urinary bladder tumour tissue samples. Pathobiol. J. ImmunoPathol Mol. Cell. Biol. 83, 252–257. https://doi.org/10.1159/000445120000445120 (2016). [pii].

Gihbid, A. et al. Prevalence of Polyomaviruses and herpesviruses in Moroccan breast Cancer. Pathogens 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12050640 (2023).

Moens, U., Prezioso, C. & Pietropaolo, V. Genetic diversity of the Noncoding Control Region of the Novel Human polyomaviruses. Viruses 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/v12121406 (2020).

Gosert, R. et al. Polyomavirus BK with rearranged noncoding control region emerge in vivo in renal transplant patients and increase viral replication and cytopathology. J. Exp. Med. 205, 841–852. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20072097 (2008).

Hirsch, H. H., Kardas, P., Kranz, D. & Leboeuf, C. The human JC Polyomavirus (JCPyV): virological background and clinical implications. APMIS: Acta Pathologica Microbiol. et Immunol. Scand. 121, 685–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/apm.12128 (2013).

Gosert, R., Kardas, P., Major, E. O. & Hirsch, H. H. Rearranged JC virus noncoding control regions found in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy patient samples increase virus early gene expression and replication rate. J. Virol. 84, 10448–10456. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00614-10 (2010).

Moens, U., Song, X., Van Ghelue, M., Lednicky, J. A. & Ehlers, B. A role of Sp1 binding motifs in basal and large T-Antigen-Induced promoter activities of human polyomavirus HPyV9 and its variant UF-1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18112414 (2017).

Ajuh, E. T. et al. Novel Human Polyomavirus non-coding control regions differ in bi-directional gene expression according to host cell, large T-antigen expression, and clinically occurring rearrangements. J. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02231-17 (2018).

Jeles, K., Katona, M. & Csoma, E. Seroprevalence of Four Polyomaviruses Linked to Dermatological Diseases: New Findings and a Comprehensive Analysis. Viruses 14, doi: (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/v14102282

Kamminga, S. et al. Development and evaluation of a broad bead-based multiplex immunoassay to measure IgG seroreactivity against human polyomaviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01566-17 (2018).

Nicol, J. T. et al. Age-specific seroprevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus, human polyomaviruses 6, 7 and 9 and Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 20, 363–368 (2013).

Csoma, E., Bidiga, L., Mehes, G., Katona, M. & Gergely, L. Survey of KI, WU, MW, and STL Polyomavirus in Cancerous and non-cancerous lung tissues. Pathobiol. J. ImmunoPathol Mol. Cell. Biol. 85, 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1159/000481174 (2018).

Rockett, R. J. et al. Detection of Novel Polyomaviruses, TSPyV, HPyV6, HPyV7, HPyV9 and MWPyV in Feces, Urine, Blood, Respiratory Swabs and Cerebrospinal Fluid. PloS one 8, doi:ARTN e6276410.1371/journal.pone.0062764 (2013).

Liimatainen, H. et al. Next-generation sequencing shows marked rearrangements of BK Polyomavirus that favor but are not required for polyomavirus-associated nephropathy. J. Clin. Virology: Official Publication Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 122, 104215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2019.104215 (2020).

Moens, U., Van Ghelue, M., Ludvigsen, M., Korup-Schulz, S. & Ehlers, B. Early and late promoters of BK Polyomavirus, Merkel cell polyomavirus, Trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus and human polyomavirus 12 are among the strongest of all known human polyomaviruses in 10 different cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 96, 2293–2303. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.000181 (2015).

Biazik, J. M., Jahn, K. A., Su, Y., Wu, Y. N. & Braet, F. Unlocking the ultrastructure of colorectal cancer cells in vitro using selective staining. World J. Gastroenterol. 16, 2743–2753. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i22.2743 (2010).

Moens, U., Seternes, O. M., Johansen, B. & Rekvig, O. P. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation of cellular genes by SV40 large T- and small T-antigens. Virus Genes. 15, 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1007962908248 (1997).

Katona, M., Jeles, K., Kovacs, R., Csoma, E. K. I. & Polyomaviruses, W. U. and Seroprevalence Study and DNA Prevalence in SARS-CoV-2 RNA Positive and Negative Respiratory Samples. Microorganisms 10, doi: (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10040752

Katona, M., Jeles, K., Takacs, P. & Csoma, E. DNA and seroprevalence study of MW and STL polyomaviruses. J. Med. Virol. 96, e29860. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.29860 (2024).

Csoma, E. et al. Study of Karolinska Institutet and Washington University polyomaviruses in tonsil, adenoid, throat swab and middle ear fluid samples. Future Microbiol. 13, 1719–1730. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb-2018-0280 (2018).

Christophe-Hobertus, C. & Christophe, D. Delimitation and functional characterization of the bidirectional THOX-DUOXA promoter regions in thyrocytes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 317, 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2010.01.001 (2010).

Tamura, K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G + C-content biases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 9, 678–687. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040752 (1992).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096 (2018).

Leigh, J. W. & Bryant, D. POPART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 1110–1116. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12410 (2015).

Funding

This research was funded by National Research, Development and Innovation Office (FK 128533). Project no. TKP2021-EGA-19 has been implemented with the support provided from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary, financed under the TKP2021-EGA funding scheme. The research activity of Eszter Csoma was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship (BO/00212/18/5) from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The research activity of Krisztina Jeles was supported by the ÚNKP-23-4-I-DE-178 New National Excellence Program of The Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Cs.; investigation, E.Cs., M.K. and K.J.; methodology, E.Cs., M.K., K.J. and P.T.; resources, E.Cs.; supervision, E.Cs.; validation, E.Cs.; visualization, E.Cs., M.K., K.J. and P.T.; writing, E.Cs., M.K., K.J. and P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. M.K. and K.J. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Katona, M., Jeles, K., Takács, P. et al. Prevalence and in vitro study of human polyomavirus 9. Sci Rep 14, 29313 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80806-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80806-3