Abstract

Impaired mucociliary transport is a distinguishing sign of cystic fibrosis, but current methods of evaluation are invasive or expose young patients to ionizing radiation. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging may provide a feasible alternative. We formulated a cationic microbubble ultrasound contrast agent, to optimize adhesion to the respiratory mucus layer when inhaled. Potential toxicity was evaluated in human bronchial epithelial cell (hBEC) cultures following a 24-hour exposure, compared to positive and negative control conditions. In vivo tolerability and pulmonary image enhancement feasibility were evaluated in mice, comparing oropharyngeal administration of contrast agent to saline control. When induced to flow across mucus plated on microscope slides, cationic microbubbles demonstrated greater affinity for target samples than standard microbubbles. Cationic microbubbles elicited no proinflammatory or cytotoxic response in hBECs, nor were any cross-links to the cilia observed. Unlike standard microbubbles, cationic microbubbles mixed into the mucus layer, without epithelial absorption, and were observed to move with the mucus layer by the action of mucociliary transport. When administered to mice, cationic microbubbles enhanced sonographic visualization of the trachea, and were well-tolerated with no adverse effects. This developmental work supports the safety and feasibility of a mucus-targeting contrast agent that may be useful for pulmonary ultrasound applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Highly effective modulator therapy (HEMT) has revolutionized the clinical management of cystic fibrosis (CF). However, the optimum timing to initiate HEMT has not been established, and safe, physiologically meaningful tools to evaluate the influence of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulation on lung function in pediatric patients are limited1. Impaired mucociliary transport is a distinguishing sign of cystic fibrosis (CF)2, and can be directly quantified by tracking the movement of particles along the mucociliary escalator using fiberoptic bronchoscopy3,4,5 or intranasal optical coherence tomography6. These techniques are both invasive, however, and require sedation or anesthesia. An indirect method of mucociliary transport function, measuring the percent clearance of inhaled technetium99m-sulfur colloid on gamma scintigraphy imaging, is more widely used in clinical evaluation7,8. However, despite standardization of protocols, radioisotope exposure remains an important clinical consideration8. Although CF was historically only a disease of childhood, the life expectancy has now increased to 48 years9, which demands consideration of cumulative radiation exposure and its long-term effects10. These observations underscore the clinical need to develop a sensitive, reproducible, non-ionizing assessment of lung function and mucociliary clearance, particularly for longitudinal evaluations requiring recurrent testing.

As an alternative to invasive or ionizing pulmonary imaging modalities, we are developing an inhalable ultrasound contrast agent, which can be used to quantify mucociliary transport and enhance pulmonary imaging. Ultrasound is accessible, inexpensive, non-ionizing, and suitable for pediatric use but is underutilized in pulmonology applications due to poor image quality11,12. In previous work, we demonstrated enhanced sonographic visualization of an ex vivo pig trachea by releasing a nebulized microbubble ultrasound contrast agent as an aerosol through the lumen13, as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. The inhaled contrast agent was observed to coat the airway inner lining, with clear delineation of the tracheal wall. However, adhesion to the respiratory surface proved inconsistent, motivating refinement of the chemical formulation. Herein, we describe the chemical formulation, in vitro evaluation (authentication, validation, safety), and in vivo assessment (tolerability and imaging feasibility) of a mucus-targeting inhalable ultrasound contrast agent that may be used to enhance pulmonary imaging and measure mucociliary transport.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the UNC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. In this investigation, we evaluated C57BL/6 mice and human bronchial epithelial cell (hBEC) cultures. The mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Cell cultures originated from 4 adult, healthy, de-identified donors (2 male, 2 female). Donated cells were obtained from the Marsico Lung Institute Tissue Procurement Core facility at the University of North Carolina. Analytic testing of hBEC cultures and associated respiratory mucus were deemed “Not Human Subjects Research” by the UNC Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Contrast agent design considerations

To optimize pulmonary imaging, we designed an inhalable ultrasound contrast agent formulated to adhere to the airway inner surfaces. A gel mucus layer coats the large airways at the air-epithelium interface14, and can be targeted by ligands (e.g., chitosan, hyaluronan)15 or by imparting a surface charge onto aerosolized compounds16. Because the mucus layer covering the epithelium has a mesh spacing of less than 300 nm17, we designed a polydisperse contrast agent with diameters ranging from 1 to 5 μm, which is consistent with intravenously administered contrast agents that are used clinically18. The micron-scale diameter was selected to ensure the contrast agent remained within the airway surface layer with minimal epithelial absorption.

Chemical formulation of cationic microbubble contrast agent

Mucus-targeting contrast agent was synthesized in house, using 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC) and polyoxyethylene (40) stearate (PEG 40-S) to create the microbubble lipid outer shell. Because muco-adhesion is amplified by positive charge19, the lipid mixture included 1,2-distearoyl-3-trimethylammonimum-propane (TAP) to yield a cationic surface20. The cationic lipid mixture (12 mol% TAP, 34 mol% PEG40-S, and 54 mol% DSPC; TAP-lipid)20 was heated in propylene glycol (PG) at 60 C for 1 h with sonication to create a dissolved suspension21. The aqueous lipid stock solution (4.67 mM total lipid concentration) contained 15% (v/v) propylene glycol and 5% (v/v) glycerol in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as the diluent (PBS-PGG). TAP-lipid solutions containing 1-, 2-, and 3-mM total lipid were created by diluting the stock cationic lipid solution with PBS-PGG. Lipid solutions (1.5 mL) were packaged into 3 mL serum vials, sealed with silicone septa, and the air in the headspace was removed and exchanged with perfluorobutane (C4F10), an inert, high molecular weight gas. Once prepared, TAP-lipid solutions and vials of lipid solution were stored at 4ºC. To create gas-filled microbubble emulsions, sealed vials containing room-temperature TAP-lipid solutions and perfluorocarbon gas were shaken in a VialMix (Lantheus Medical Imaging, N. Billerica, MA; 4500 rpm, 45 s). The diameter and yield of TAP-microbubbles were determined for microbubbles prepared from 1, 2, and 3 mM TAP-lipid solutions using an Accusizer FX Nano system (Entegris, Billerica, MA).

Stability of cationic microbubble contrast agent

We compared the stability of our cationic, TAP-microbubbles to standard microbubbles by measuring mean diameters and concentrations over time, at room temperature and at 37 ºC. Diameters and concentrations were measured in triplicate at each timepoint and averaged. Our standard microbubble contrast agent was formulated in-house, as previously described22, from a 1 mM lipid solution containing a (9:1) molar ratio of DSPC to 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000) to create a lipid shell (DSPC/P2K) around a core of C4F10 gas. To facilitate comparisons of stability, TAP and standard microbubbles were diluted to approximately the same concentrations, with microbubble diameters and concentrations observed at room temperature over time (0, 1, 2, and 3 h). Stability was also evaluated after a 1-hour incubation at 37 ºC, to approximate the expected length of time for a clinical ultrasound.

Verification of positive charge

Electrostatic charge was quantified for our standard microbubble formulation versus TAP microbubbles using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Panalytical; Malvern, U.K.). For both formulations, an approximately 1 × 108 /mL concentration was measured in 1 mM KCl and averaged across 6 replicates.

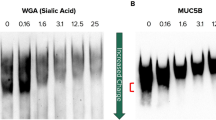

Authentication of mucus-targeting

To verify the association of our cationic contrast agent with the respiratory mucus layer, we observed the movement and distribution of TAP microbubbles versus our standard microbubbles relative to a target mucus sample. Cationic (TAP) or standard contrast agents were enriched for larger diameter microbubbles to facilitate capturing photomicrographs of microbubble-mucus interactions at 400X magnification. To accomplish this, TAP or standard microbubbles were centrifuged (1–2 min, 160x g) in sealed 5-mL syringes. The smaller diameter microbubbles in the infranatant fluid were separated and discarded from the floating ‘cake’ of larger microbubbles. Larger microbubbles were resuspended in PBS-PGG, with the centrifugal enrichment repeated 3 times before determining the final concentration and size distribution of ‘large’ microbubbles, as shown in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3. Clean glass slides were plated with respiratory mucus from a healthy donor and allowed to dry overnight. A 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution in PBS was used to rehydrate the mucus and block the rectangular area surrounding the mucus sample. After blocking, 50 µL of contrast solution was pipetted onto the BSA-blocked area. The slide was tipped to allow contrast to flow over the mucus area, then inverted to allow contrast to “float” up against the mucus sample. After a 1-minute inversion to allow flotation, the slide was dipped into PBS to remove unbound microbubbles. The slide was wiped to restore the rectangular wetted area around the region of interest, and PBS was added to couple a water-immersion objective lens optically. The spatial arrangement of microbubbles was observed microscopically at 400X, and photomicrographs were captured to document microbubble-mucus interactions.

Mucociliary transport

A mucociliary transport assay23 was used to quantify the movement of TAP versus standard microbubbles on human bronchial epithelial cell cultures, with a fluorescent lipophilic cationic indocarbocyanine dye (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, Vybrant™ DiO) used for labeling. As described24, the in vitro transport assay was created in house by affixing a central ring to a Millicell culture insert, which was etched to form circular “racetracks” around the perimeter. First passage primary hBECs were cultured and plated on the Millicell insert and allowed to grow for 2–3 weeks until confluent. As previously noted, hBEC cultures achieve continuous directional mucociliary transport when grown on the patterned substrate25.

Mucociliary transport assays are coated by a mucus layer at the air surface interface, allowing direct, in vitro quantification of mucociliary transport.

To perform the transport assay, a culture was first incubated for 5 min with 1 ml of PBS with calcium and magnesium at 37 °C to rehydrate the mucus. The surface fluid was then removed and 20 µL volume of microbubble solution (either TAP or standard contrast agent, concentrated to 200,000 microbubbles/µL), was pipetted onto one position in the center of the track. The culture was then placed in an OkoLab microscope incubator. The incubator was maintained at 37 °C and humidified air with 5% CO2 flowing through the culture chamber at 400 ml/min. The culture was allowed to equilibrate for ten minutes. Videos were captured from eight equally spaced fields in the center of the track using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc, Melville, NY, USA) and a Basler acA1300-200 um camera controlled by SAVA software (version 2.0.8 W, Ammons Engineering, Clio, MI, USA)26. At each field of view, a transmitted light video was taken using phase optics (20x ELWD objective) and a 120 frame/second capture rate. Then immediately following that video, a fluorescence video was taken of the same field of view with a 15 frames per second (fps) capture rate. The fluorescence excitation was provided by a Lumencor SOLA 5-LCR-VG LED source (Lumencor; Beaverton, OR) and the light path used a Nikon B-2E/C filter block. To measure transport, a particle position was manually recorded at two locations in each video. To standardize the comparison of transport rates for our TAP and standard microbubbles, transport assays were cultured from the same healthy, human donor. As a validation, the calculated transport of fluorescence was compared with the transport rate of visible debris within the same field of view, captured on transmitted light video at 15 fps. Statistical comparisons (correlation and agreement) were carried out using Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365 (https://www.microsoft.com). Evidence of cross-links between contrast agent and cilia was visually monitored, for each of the 8 fields of view, as a safety objective. Epithelial absorption was identified by fluorescence beneath the cilia, with the proportion quantified relative to the entire area for each field of view.

Cytotoxicity and proinflammatory response

Potential biological effects of our TAP microbubble were tested using primary hBEC cells collected from 4 donor lungs, which were differentiated at an air-liquid interface on 12 mm Transwell permeable support membranes (Corning, Glendale, AZ) to a mucociliary phenotype. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-8 (IL-8) were quantified according to manufacturer instructions (CyQUANT LDH Cytotoxicity Assy, Invitrogen and OptEIA Human IL-8 ELISA, BD Biosciences, respectively) in the basolateral medium following a 24-hour apical exposure to either 25 µL of undiluted TAP-contrast (with the microbubbles activated by mechanical agitation), 25 µL of undiluted vehicle control (TAP lipids), 25 µL saline control, or a no-treatment control. As positive controls, one Transwell insert from each donor was treated with 4% Triton X-100 to lyse cells and provide maximal LDH release, and one Transwell insert was treated with 10ng/mL of each IL-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF alpha) to produce maximum IL-8 proinflammatory response. Donor-specific release of LDH and IL-8 were quantified in triplicate for each exposure condition and averaged. Potential biological effects of TAP-microbubble contrast agent were statistically analyzed by comparing each exposure condition with both the negative and positive control conditions, using paired t-tests. Normalized concentrations of LDH and IL-8 release were compared using paired t-tests, by normalizing each exposure condition to the positive control. Statistical testing was carried out using Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365 (https://www.microsoft.com).

In vivo safety, tolerability, and imaging feasibility

To examine the in vivo tolerability, safety, and pulmonary imaging feasibility of our inhaled ultrasound contrast agent, we evaluated six C57BL/6 mice (8–12 weeks, all female). Mice were randomly allocated to 50 µL administration of either TAP microbubble contrast agent (n = 3 mice), or sterile saline control (n = 3). Because mice are obligate nose breathers, the controlled dose was administered to the lung using an established oropharyngeal aspiration technique27. Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane (indicated by depressed breathing and testing for righting reflex) and positioned supine on a recumbent imaging stage, in reverse Trendelenburg orientation, with the tongue extended from the mouth and hung to the side. A controlled amount (50 µL) of contrast agent or saline was instilled onto the oropharynx, using a gel loading micropipette tip. Immediately following oropharyngeal aspiration, mice were imaged in contrast mode using a FUJIFILM Vevo F2 ultrasound machine interfaced with a 15.0–29.0 MHz transducer, capturing at a frame rate of 30 fps and dynamic range of 57 dB. The trachea was imaged in longitudinal orientation, with the ultrasound transducer positioned by a stereotactic clamp, directly onto the mouse’s depilated skin without a standoff pad, using ultrasound gel as the coupling agent. To quantify tracheal image enhancement, contrast-to-noise ratios (CNRs) were calculated, with microbubble signal linearized as previously described28. CNRs were quantified from representative regions of interest, for mice administered TAP microbubble contrast agent versus saline control. Mice were observed during the imaging procedure for signs of distress, and for 7 days post-procedure by monitoring weight, grooming, and body condition score. After monitoring for acute effects for 7 days, mice were euthanized by lethal dose of carbon dioxide followed by secondary means (cervical dislocation or thoracotomy), in accordance with American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines. The trachea and lungs were harvested and preserved in formalin, with tissues fixed with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. Histology was evaluated by an independent, veterinary pathologist who was blinded to the exposure condition. With a sample size of 3 mice per group, we expected 96% power a priori, to detect group-specific adverse effects with statistical significance, if occurring in 2 or more mice.

Results

TAP-microbubbles, emulsified from C4F10 gas and a 2 mM aqueous solution of lipids containing 12 mol% TAP, 34 mol% PEG40-S, and 54 mol% DSPC, yielded an average microbubble concentration of 2 × 109/mL. Microbubble diameters were polydisperse, ranging from ~ 0.27 to 10 μm. For evaluation, we selected TAP-microbubbles > 0.5 μm, which had a mean diameter of 0.78 ± 0.33 μm when stored overnight at 4 ○C, and 0.81 ± 0.32 μm when stored at room temperature. When observed across a 3-hour observation at room temperature, the diameters and concentrations of TAP and standard microbubbles were stable and consistent (Supplementary Figure S4). However, when incubated at 37 ºC for 1 h, the concentrations decreased by 50% for TAP microbubbles, and by 25% for standard microbubbles. Concurrently, the mean diameters for TAP microbubbles increased from 0.8 microns to approximately 1 micron (a 25% change) while standard microbubbles maintained a diameter of 0.9 microns (Supplementary Figure S5).

Zeta potential, a measure of electrostatic charge, was − 18.25 ± 0.46 mV for our standard microbubble formulation, and + 4.07 ± 0.61 mV for our TAP microbubbles. When large (4 μm) TAP microbubbles were suspended in saline and induced to flow across human respiratory mucus plated on a microscope slide, the microbubbles oriented in a spatial arrangement in proximity to the mucus (Fig. 1a). By comparison, our standard microbubbles demonstrated no affinity for mucus (Fig. 1b), and freely flowed as a bulk liquid on the microscope slide, in a uniform distribution with no clustering around the mucus sample. Unlike TAP-microbubbles, the standard microbubbles appeared to float above the mucus layer on a different plane, with no interaction or adhesion to the sample.

Cationic TAP microbubbles (MB) remained bound to human mucus after washing with PBS (a). Standard, in-house MB contrast agent did not remain bound to human mucus after washing with PBS (b). Depicted in the lower right of each micrograph is a 5-micron scale bar (red). Note that both contrast agents were enriched for larger diameter MB before the binding experiment, as described in the Methods.

When imaged by high frame rate video microscopy on mucociliary transport assays, TAP-microbubbles were easily visualized as bright, fluorescent clouds on epifluorescence video (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Video S6), with transport successfully tracked in 8 fields of view in the center of the track and evenly distributed along the full length of the track. By comparison, fluorescently tagged standard microbubbles were faint and poorly visualized in the mucus layer, and transport rates could not be quantified. The calculated transport rate of TAP-microbubble fluorescent clouds ranged from 90 to 150 μm/s and was in close correlation (r = 0.94; P-value = 0.0006) and agreement (6% fractional difference) with the calculated transport rate of visible debris on transmitted light video (Fig. 3). The mean ciliary beat frequency for the in vitro assay was 12.2 ± 0.8 Hz, with a mean active ciliated area of 29.2 ± 16%, across the 8 fields of view. There was no observable evidence of cross-linking between TAP-microbubbles and the cilia, in any of the 8 fields of view. Epithelial absorption was observed to be minimal and temporary, averaging at 0.8% across all fields of view during the 60 s observation period.

Time-lapse movement of fluorescently labeled TAP microbubbles on a human bronchial epithelial cell culture. Panel (a): transmitted light video, panel (b): epifluorescence video. Panels show the same field of view, with fluorescently labeled particles similar in size and motion to those seen in the transmitted light images. Scale bar: 20 μm.

Exposing human bronchial epithelial cell (hBEC) cultures to TAP-microbubbles for a duration of 24 h did not induce cytotoxicity or inflammation, as assessed by the cellular release of LDH (a biomarker of cytotoxicity) or IL-8 secretion (a biomarker of proinflammatory response) which were normalized to the positive control conditions (Fig. 4). Normalized concentrations of LDH were not significantly increased when comparing TAP microbubble exposure to saline control (3.8% vs. 3.7%; P = 0.12) or when comparing vehicle exposure to saline control (3.8% vs. 3.7%; P = 0.13). In the event that saline itself may induce inflammation, we also compared LDH release following exposure to saline versus no-exposure control; again, with no significant difference (3.7% vs. 3.5%; P = 0.6). As expected, the positive control (Triton X-100) induced significant cytotoxicity (100%). The 24-hour exposure to TAP microbubbles demonstrated no effect on secretion of proinflammatory cytokine IL-8, either. Normalized concentrations were comparable for TAP microbubble exposure versus saline (12% vs. 9%; P = 0.4) and for vehicle exposure versus saline (15% vs. 9%; P = 0.3). There was also no statistically significant difference in normalized IL-8 concentration when comparing saline to a no-exposure control (9% for both). Again, as expected, the positive control (IL-1β and TNF⍺) did induce IL-8 production (P = 0.02), compared to the saline control.

Cytotoxic (lactate dehydrogenase release) and proinflammatory response (interleukin-8 secretion) induced by exposing human bronchial epithelial cell cultures to TAP microbubble contrast agent, TAP microbubble vehicle, and saline. Abbreviations: LDH = lactate dehydrogenase, IL-8 = interleukin-8, TAP = 1,2-distearoyl-3-trimethylammonimumpropane, Il-1B = interleukin-1 beta, TNFa = tumor necrosis factor alpha. Error bars = standard deviations.

When we performed pulmonary ultrasound of mice in vivo, the imaging procedure was well tolerated by all mice, irrespective of allocation to TAP microbubbles or saline control. Administration of saline control had no demonstrated effect on image enhancement or pulmonary structure delineation. By comparison, the entire length of the trachea was brightly visualized following oropharyngeal administration of TAP microbubbles (Fig. 5). Consistent with qualitative interpretations, the measured CNR was higher for tracheal images with TAP microbubble contrast agent, relative to saline control (66.7 dB vs. 13.4 dB). No acute, adverse effects were observed during the 7-day, post-exposure monitoring period, for allocation to either contrast agent or saline. Similarly, there were no signs of inflammation or injury by histology (Supplementary Figure S7).

Comparison of in vivo tracheal ultrasound following oropharyngeal administration of saline versus TAP microbubble. Panels: Anatomical slice of mouse trachea (a). Ultrasound b-mode (b, d) and contrast mode (c, e) of a mouse trachea post-saline (b, c) and post inhalation of TAP microbubbles (d, e). Images acquired using a FUJIFILM VisualSonics Vevo F2. Anatomic slice of mouse trachea (panel a) was acquired by computed tomography and is courtesy of IMAIOS “Micheau A, Hoa D, e-Anatomy, www.imaios.com, DOI: https://doi.org/10.37019/e-anatomy”.

Discussion

In this experimental work, we have formulated a cationic ultrasound contrast agent that is optimized for muco-adhesion, which may have future applications for evaluation of lung function and mucociliary clearance. We were able to show that our TAP-microbubble contrast agent associated with mucus and traveled with the mucus layer in vitro, by evaluating mucociliary transport assays composed of human bronchial epithelial cells. The microbubbles mixed into the air-surface layer, without absorption into the epithelium, promoting the feasibility of TAP contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging as a means to evaluate mucociliary transport. Our TAP-microbubble contrast agent demonstrated no cytotoxic or proinflammatory response to human bronchial epithelial cells cultures following 24-hour exposure, nor were any ciliary cross-links observed, which suggests feasibility for clinical use, pending further evaluation. When administered to mice, TAP-microbubble contrast agent enhanced tracheal ultrasound imaging and was well tolerated in vivo, with no adverse effects noted on lung histology.

One clinical application for our optimized contrast agent may be evaluation of mucociliary clearance, by quantifying the overall percent clearance of visible microbubbles across a specified time interval (similar to the approach used by gamma scintigraphy). Assessment of mucociliary clearance time could potentially be performed using commercially available equipment. If deemed safe for clinical use, the contrast agent could be administered to the patient as an aerosol using a medical grade nebulizer. We have previously shown that our microbubble contrast agent remains intact following the nebulization process, and that nebulized microbubbles can be visualized using clinical ultrasound scanners interfaced with commercial contrast-mode imaging packages13. In clinical scenarios, the trachea could be imaged without bone obstruction, providing a clear window to evaluate mucociliary clearance time. This could be quantified by the elapsed time for contrast signal to diminish, as microbubbles on the airway surfaces are cleared by the action of the mucociliary escalator. One caveat, however, is the known diminishment in microbubble concentrations over time, at 37 ºC. As with gamma scintigraphy, which accounts for the radioactive decay of technicium-99 over time, temporal evaluation of microbubble signal clearance would need to incorporate a correction factor for microbubble concentrations. In future preclinical evaluations, we will compare signal clearance time in normal controls versus mice designed to express a cystic fibrosis phenotype29, and validate both against gamma scintigraphy.

A different approach to evaluate bulk mucociliary transport would be to quantify the “flash-replenishment” time, which could be accomplished by selectively destroying microbubbles in a region of interest and recording the time for contrast signal to return as distal microbubbles are transported up the mucociliary escalator. Flash-replenishment time is accessible with clinical scanners and commercially available image analysis packages30, but its safe use in pulmonary applications, and particularly in patients with CF, has not been evaluated. With this technique, microbubbles are destroyed by increasing the ultrasound system insonation power, rupturing the microbubbles through induced cavitation. It is possible that the violent destruction of microbubbles lodged within the mucus layer may adversely affect ciliary function. Conversely, it is also a possibility that microbubble cavitation may be therapeutic, by breaking apart the thickened mucus in patients with CF and facilitating its clearance from the respiratory tract. However, both scenarios are speculative and as of yet untested.

Rather than relying upon the bulk clearance (or replenishment) of contrast signal for assessment of mucociliary function, TAP contrast agent could potentially be used to measure mucociliary transport rate. The in vitro transport rates that we calculated for TAP microbubbles on microscopy ranged from 90 to 150 μm/s, velocities that are too low to be captured by conventional Doppler, but within the range quantifiable by acoustic angiography, a contrast-enhanced superharmonic ultrasound imaging technique31,32. Acoustic angiography is a developing ultrasound technique which uses a dual frequency transducer to selectively receive the superharmonic echoes arising from contrast microbubbles, with high signal to noise but without background from tissue. Acoustic angiography techniques, which can assess microbubble movement or decorrelation over multiple frames, may be particularly useful for mapping heterogeneity in transport rates arising from localized regions of ciliary discoordination. Although currently undemonstrated, the mucociliary transport rate could potentially be quantified from the time for contrast signal intensity to peak, using a flash-replenishment approach, or by quantifying the rate of contrast signal intensity decay as microbubbles are cleared by the action of mucociliary escalator.

Mucociliary transport rate could also be measured by tracking the motion of individual microbubbles along a specified distance in the trachea (similar to invasive particle tracking by fiberoptic bronchoscopy3,4,5 or intranasal optical coherence tomography6). Super-resolution ultrasound is an imaging technique capable of tracking individual microbubbles in the circulation, and may also have applications in pulmonary imaging. Although not performed by routine imaging equipment, super-resolution ultrasound imaging achieves resolution beyond the diffraction limit of conventional coherent imaging and can resolve 25–50 micron single bubble displacements over 1 s33,34. In future preclinical work, we will evaluate the accuracy of super-resolution ultrasound imaging against video microscopy in mice with and without a CF phenotype. Current microscopic techniques are facilitated by removing the mouse jaw or the tissue covering the trachea, and by the continued beating of cilia for up to 30 min post-mortem35,36. Unlike microscopy, super-resolution ultrasound acquires images transcutaneously, and is suitable for in vivo applications at depths up to 6 cm37. However, the technique is very sensitive to motion, and in clinical settings, preschool aged children would almost certainly require sedation or anesthesia to remain still for image acquisition. With this consideration, mucociliary clearance time or mucociliary transport rate measured by acoustic angiography may be more feasible imaging markers of mucociliary function than direct measurement of mucociliary transport rate by super-resolution ultrasound. These translational aspects remain to be evaluated in future work.

In conclusion, we have presented preliminary findings supporting the safety and feasibility of a mucus-targeting contrast agent that may be useful for pulmonary imaging applications.

Data availability

The quantitative data supporting the statistical analysis in this study will be made available upon request to the corresponding author: caughey@med.unc.edu.

References

Bell, S. C. et al. The future of cystic fibrosis care: a global perspective. Lancet Respir Med. 8, 65–124 (2020).

Robinson, M. & Bye, P. T. B. Mucociliary clearance in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 33, 293–306 (2002).

Olivieri, D., Del Donno, M., Casalini, A., D’Ippolito, R. & Fregnan, G. B. Activity of Erdosteine on Mucociliary Transport in patients affected by chronic bronchitis. Respiration 58, 91–94 (1991).

Keller, C. & Brimacombe, J. Bronchial Mucus Transport Velocity in Paralyzed anesthetized patients. Anesth. Analg. 86, 1280–1282 (1998).

Seo, H., Kim, S. H., Choi, J. H., Hong, J. Y. & Hwang, J. H. Effect of heated humidified ventilation on bronchial mucus transport velocity in general anaesthesia: a randomized trial. J. Int. Med. Res. 42, 1222–1231 (2014).

Leung, H. M. et al. Intranasal micro-optical coherence tomography imaging for cystic fibrosis studies. Sci. Transl Med. 11, eaav3505 (2019).

Donaldson, S. H. et al. Mucus clearance and lung function in cystic fibrosis with hypertonic saline. N Engl. J. Med. 354, 241–250 (2006).

Bennett, W. D. et al. Multisite comparison of Mucociliary and Cough Clearance measures using standardized methods. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm Drug Deliv. 26, 157–164 (2013).

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry. Annual Data Report. https://cff.org/Research/Researcher-Resources/Patient-Registry/2019-Patient-Registry-Annual-Data-Report.pdf (2019). (2019).

O’Connell, O. J. et al. Radiologic Imaging Cyst. Fibros. Chest 141, 1575–1583 (2012).

Lovrenski, J. Pediatric lung ultrasound — pros and potentials. Pediatr. Radiol. 50, 306–313 (2020).

Tomà, P. Lung ultrasound in pediatric radiology - cons. Pediatr. Radiol. 50, 314–320 (2020).

Clapp, P. W. et al. Feasibility of an Inhalable Ultrasound Contrast Agent to Enhance Airway Imaging. BioRxiv (2021). https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.27.446053

Bustamante-Marin, X. M. & Ostrowski, L. E. Cilia and Mucociliary Clearance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 9, a028241 (2017).

Liu, X. B. et al. Pulmonary delivery of scutellarin solution and mucoadhesive particles in rats. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 70, 845–852 (2008).

Fromen, C. A. et al. Nanoparticle surface charge impacts distribution, uptake and lymph node trafficking by pulmonary antigen-presenting cells. Nanomedicine 12, 677–687 (2016).

Schneider, C. S. et al. Nanoparticles that do not adhere to mucus provide uniform and long-lasting drug delivery to airways following inhalation. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601556 (2017).

Gessner, R. & Dayton, P. A. Advances in molecular imaging with ultrasound. Mol. Imaging. 9, 117–127 (2010).

Boddupalli, B., Mohammed, Z. N. K., Nath, R. & Banji, D. Mucoadhesive drug delivery system: an overview. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 1, 381 (2010).

Christiansen, J. P., French, B. A., Klibanov, A. L., Kaul, S. & Lindner, J. R. Targeted tissue transfection with ultrasound destruction of plasmid-bearing cationic microbubbles. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 29, 1759–1767 (2003).

Weinkauf, C. C. et al. Endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 is a marker for high-risk carotid plaques and target for ultrasound molecular imaging. J. Vasc Surg. 68, 105S–113S (2018).

Talu, E. et al. Tailoring the Size Distribution of Ultrasound Contrast Agents: Possible Method for Improving Sensitivity in Molecular Imaging. Mol Imaging 6, 7290.00034 (2007). (2007).

Sears, P. R. et al. Induction of ciliary orientation by matrix patterning and characterization of mucociliary transport. Biophys. J. 120, 1387–1395 (2021).

Sears, P. R., Yin, W. N. & Ostrowski, L. E. Continuous mucociliary transport by primary human airway epithelial cells in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 309, L99–108 (2015).

Sears, P. R. & Ostrowski, L. E. Mucociliary Transport Device Construction and application to Study Mucociliary Clearance. in 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-3507-0_17 (2024).

Sisson, J. H., Stoner, J. A., Ammons, B. A. & Wyatt, T. A. All-digital image capture and whole-field analysis of ciliary beat frequency. J. Microsc. 211, 103–111 (2003).

Nielsen, T. B., Yan, J., Luna, B. & Spellberg, B. Murine Oropharyngeal Aspiration Model of Ventilator-associated and hospital- acquired bacterial pneumonia. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3791/57672 (2018).

Tsuruta, J. K. et al. Optimizing ultrasound molecular imaging of secreted frizzled related protein 2 expression in angiosarcoma. PLoS One. 12, e0174281 (2017).

Livraghi-Butrico, A. et al. Lung disease phenotypes caused by over-expression of combinations of alpha, beta, and gamma subunits of the epithelial sodium channel in mouse airways. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00382.2017 (2017).

Greis, C. Quantitative evaluation of microvascular blood flow by contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). Clin. Hemorheol Microcirc. 49, 137–149 (2011).

Lindsey, B. D. et al. High resolution Ultrasound Superharmonic Perfusion Imaging: in vivo feasibility and quantification of dynamic contrast-enhanced acoustic angiography. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 45, 939–948 (2017).

Newsome, I. G., Kierski, T. M. & Dayton, P. A. Assessment of the Superharmonic Response of Microbubble Contrast Agents for Acoustic Angiography as a function of Microbubble parameters. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 45, 2515–2524 (2019).

Christensen-Jeffries, K. et al. Super-resolution Ultrasound Imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 46, 865–891 (2020).

Kierski, T. M. et al. Superharmonic Ultrasound for Motion-Independent localization Microscopy: applications to Microvascular Imaging from Low to High Flow Rates. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 67, 957–967 (2020).

Rogers, T. D., Ostrowski, L. E., Livraghi-Butrico, A., Button, B. & Grubb, B. R. Mucociliary Clearance in mice measured by Tracking Trans-tracheal fluorescence of nasally aerosolized beads. Sci. Rep. 8, 14744 (2018).

Rogers, T. D. et al. Regional differences in Mucociliary Clearance in the Upper and Lower Airways. Front. Physiol. 13, 842592 (2022).

Espindola, D., Lin, F., Soulioti, D. E., Dayton, P. A. & Pinton, G. F. Adaptive Multifocus Beamforming for contrast-enhanced-Super-resolution Ultrasound Imaging in Deep tissue. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 65, 2255–2263 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rani Sellers, DVM, PhD for her expert interpretation of mouse pulmonary histology. We also thank the Particle Tracking Microrheology Cystic Fibrosis Foundation National Resource Center supported by grant HILL20Y2-OUT. We acknowledge the UNC Lineberger Preclinical Research Unit at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill which performed the animal studies and is supported in part by an NCI Center Core Support Grant (P30CA16086) to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Mr. Weitz’s imaging contributions were partially supported by NIH R01CA282648. The authors would also like to thank the Small Animal Imaging Core Facility, funded in part by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant, P30CA016086, and the NIH S10 Shared Instrumentation Grant, S10OD034328, for supporting this work.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CAUGHE23G0).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the manuscript and agree to be accountable for their contributions. M.C.C., J.K.T, P.R.S, M.E.R, A.S.W., P.G.D., and P.W.C conceptualized the experiments. J.K.T, P.R.S, M.E.R, A.S.W, and P.G.D. conducted the experiments and performed the analytic testing. M.C.C. wrote the manuscript. J.K.T, P.R.S, P.G.D, M.E.R, D.B.H., L.E.O., and P.A.D. revised the manuscript critically.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Drs. Tsuruta, Weitz, Durham, Clapp, Hill, Dayton, and Caughey are co-inventors on a pending patent describing a microbubble ultrasound contrast agent optimized for muco-adhesion and pulmonary imaging. Dr. Dayton declares ownership interest in SonoVascular and Triangle Biotechnology, as well as intellectual property licenses and royalties from Revvity, Triangle Biotechnolgy, and SonoVascular. Drs. Sears, Rebuli, and Ostrowski report no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsuruta, J.K., Sears, P.R., Rebuli, M.E. et al. Development of an inhalable contrast agent targeting the respiratory tract mucus layer for pulmonary ultrasonic imaging. Sci Rep 14, 29840 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80933-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80933-x