Abstract

This present study investigates a three-step laser isotope separation method for the enrichment of 168Er isotope using 631.052 nm – 586.912 nm – 566.003 nm three-step photoionization scheme. The lineshape contours observed in three-step photoionization process have been investigated in detail. This study shows that enrichment of 168Er isotope can be achieved with a relatively simple experimental configuration. With the derived system configuration, it has been shown that it is possible to produce 18 g/day of 90% enriched 168Er. Using the enriched 168Er isotope obtained from the laser isotope separation process, irradiation in low, medium, and high flux reactors can produce 180, 1800, and 18,000 doses per day (each with an activity of 7.4 GBq) respectively. After 24 h of irradiation and chemical separation, the radioisotopic purity of the medical isotope reaches to > 99% making it suitable for the medical applications. This is the first ever study on the laser isotope separation of 168Er isotope.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) has evolved as a very effective treatment protocol for the treatment of the non-endocrine tumours (NET). In this method, a radionuclide is tagged with an appropriate peptide or its analogue binds to the peptide receptor of the tumour cell. The radiation emitted (α or β) destroys the tumour cells thus providing an effective treatment. Among the several radioisotopes being explored for PRRT, 177Lu is widely preferred for the following reasons. 177Lu emits both β and γ radiation thus can be used for both therapeutics and diagnostics (known as theranostics) simultaneously. An excellent review on the available options for the production of 177Lu for targeted radionuclide therapy has been published in 20151. 177Lu can be produced by irradiation of its enriched precursors namely 176Lu and 176Yb. Currently, a significant shortage of these precursor isotopes is severely limiting the availability of medical isotopes for the treatment of patients in need. Several articles have been published by the Indian2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, Korean10,11 and Russian12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 researchers addressing the laser enrichment of Lu and Yb isotopes through atomic route.

169Er is an interesting isotope having a half-life of 9.392(18) days. It releases two β- particles with maximum energies of 342.9 keV (45%) and 351.3 keV (55%) and two low intensity γ-rays 109.8 keV (1.3 × 10–3%) and 118.2 keV (1.4 × 10–4%). A brief comparison of the properties of 177Lu and 169Er and their precursor isotopes is shown in Table 1. There are a number of reasons which make 169Er a promising nuclide21,22 for PRRT. They are as following.

Mean energy of β- particles (99.8 keV) released by 169Er is considerably lower than mean energy of β- particles (133.6 keV) released by 177Lu. Thus, the mean penetration depth of β- particles released by 169Er is 300 μm while it is 670 μm for the β- particles released by 177Lu. The lower mean energy of β- particles of 169Er minimises dose to the adjacent healthy tissues. Further, the gamma ray yields of 169Er are lower by several orders in comparison to the 177Lu isotope, thus minimising the dose to the non-target body tissues. Additionally, the longer half-life of 169Er isotope (9.392 days) in comparison to 177Lu isotope (6.6443 days) would enable transport of the medicine to distant and remote locations. Interestingly, the ionic radius of Er3+ (89 pm) closely matches that of Lu3+ (86 pm), therefore, the chelators currently employed for 177Lu can be effectively utilized for chelating 169Er. Finally, higher natural abundance of the precursor isotope 168Er (26.978%) facilitates increased production of the medical isotope through irradiation.

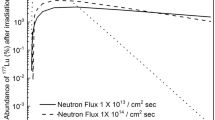

Given these aforementioned reasons, there is a need to develop efficient methods for the production of 169Er. The 169Er radioisotope is produced by irradiating the stable 168Er isotope through the 168Er(n,γ)169Er nuclear reaction. The thermal neutron absorption cross-section of the reaction is 2.74 ± 0.08 b (Table 2). When natural erbium is irradiated in a nuclear reactor, the resulting stable and radioisotopes are shown in Fig. 1. The production efficiency of 169Er from natural erbium (Fig. 2) in low (neutron flux 1 × 1013 neutrons/cm2/sec), medium (neutron flux 1 × 1014 neutrons/cm2/sec) and high (neutron flux 1 × 1015 neutrons/cm2/sec) flux reactors after 21 days of irradiation has been calculated to be 6.8 × 10–6, 7.2 × 10–5 and 9.7 × 10–4 respectively. Even when irradiated in high-flux reactors, the ratio of 169Er to the stable isotopes of erbium is expected to be as low as 1:1030. The presence of stable erbium isotopes during the radioisotope complexation process can be problematic. These stable isotopes compete with the radioactive 169Er for binding with cancer cells, which can hinder the effective delivery of the therapeutic dose to tumour cells. Therefore, using the enriched 168Er isotope is mandatory for the production of the 169Er radioisotope. When an enriched 168Er is irradiated in low, medium and high flux reactors for 21 days (Fig. 3), the production efficiency of 169Er isotope has been calculated to be 2.5 × 10–5, 2.5 × 10–4 and 2.5 × 10–3. Therefore, irradiating erbium in a high-flux reactor for 21 days can increase the ratio of 169Er to 168Er to 1:400.

Among the available methods for isotope enrichment, three are most commonly used. They are gas centrifugation, electromagnetic isotope separation and atomic vapor laser isotope separation. The gas centrifuge isotope separation process is employed to separate isotopes of elements that readily form volatile compounds, typically fluorides, which exhibit high vapor pressures near room temperatures. Enrichment of the target isotope is achieved through cascading the high-speed centrifugation process. Gas centrifugation cannot be employed for the isotope separation process of erbium due to the high melting (1146 °C) and boiling (2200 °C) points of ErF3. While electromagnetic isotope separation achieves high degrees of enrichment, the quantity of enriched isotopes produced through this method typically ranges from milligrams to grams23 primarily owing to its low ionization efficiency. Therefore, this method alone is unlikely to meet the global demand for enriched 168Er. Furthermore, both centrifugation and electromagnetic isotope separation methods are susceptible to the isobaric impurities originating from elemental impurities of the feedstock material, which could restrict the use of enriched isotopes in medical applications. Rubel Chakravarty et al.24 have studied the production and purification of 169Er for therapeutic applications particularly for the radiation synovectomy (RSV). They have observed that the co-production of 169Yb (due to the presence of 168Yb as an impurity) is a significant obstacle for the clinical use of 169Er in radioisotope therapy, necessitating electrochemical purification.

For such applications, separation methods that are not dependent on isotope mass would be more desirable. Atomic Vapor Laser Isotope Separation (AVLIS) is a method wherein the lasers are tuned to the target isotope interact with the atoms of the isotope mixture in gas phase. Atoms in their ground state are sequentially excited to higher energy states and eventually ionized. Lasers are tuned to specific frequencies that selectively excite and ionize the target isotopes, which are collected. The advantage with AVLIS process is that its single state separation efficiency is far higher than any other known isotope separation method. Since the method is not based on isotope mass, the isobaric impurities from the feedstock material are not transferred to the enriched end product, therefore, the end product is suitable for the production of 169Er medical isotope.

Previous laser isotope separation methods have typically required narrowband lasers with a bandwidth of around 100 MHz and highly collimated atomic beams to achieve the desired degree of enrichment3,6,12,13. However, it is important to note that such experimental setups are often complex and challenging to handle. In contrast, the present work investigates the laser isotope enrichment of 168Er using a simpler experimental configuration, where the excitation lasers have a bandwidth of approximately 500 MHz and the atomic beam has an angular divergence of about 30°. This considerably reduces the complexity of experimental systems. Density matrix formalism has been applied to study the laser-atom interactions in the three-step photoionization process. The effect of atomic, laser and atom source parameters on the degree of enrichment and production rate have been studied. This is the first ever study on the laser isotope separation of 168Er.

Photoionization of erbium

Erbium is an element of the lanthanide series having an atomic number of 68. It has six stable isotopes (Table 2) namely; 162Er (0.139%), 164Er (1.601%), 166Er (33.503%), 167Er (22.869%), 168Er (26.978%) and 170Er (14.910%). Among all the stable isotopes, 167Er is the only isotope that exhibits hyperfine structure due to its non-zero nuclear spin I = 7/2. Erbium has a melting point of 1529 °C and a boiling point of 2868 °C. The variation in vapor pressure and the number density of atoms with source temperature is shown in Fig. 4A. At 1200 °C, the vapor pressure of erbium has been calculated to be 8.1 μbar and the corresponding number density is 4 × 1013 atoms/cm3.

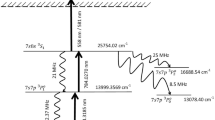

Erbium has a ground state electronic configuration of 4f126s2 3H6 (0.0 cm-1). The energy of the next low-lying metastable state is 4f126s2 3F4 (5035.193 cm-1). At this 1200˚C, the population of the ground state is 99.2% (Fig. 4B). Therefore, photoionization scheme for the laser isotope separation of erbium must originate from the 4f126s2 3H6 (0.0 cm-1) ground state. The first ionization energy25 of erbium is 49,238 cm-1 (6.105 eV). Since energy of the photons in the visible region is about 17,000 cm-1 (2.1 eV), it requires three photons for the photoionization of erbium atoms.

A very few studies have been reported so far on the laser isotope separation of erbium26,27,28. Among them, Karlov et al.26,27 have used \(4{f}^{12}6{s}^{2}{}^{3}{H}_{6} \left(0.0 {cm}^{-1}\right)\stackrel{582.842 nm}{\to }4{f}^{12}6s6p {\left(\text{6,1}\right)}^{o} J=7 \left(17157.307 {cm}^{-1}\right) \stackrel{mercury-lamp}{\to }{Er }^{+}\) photoionization scheme for the separation of erbium isotopes. This scheme cannot be adopted for the large scale separation of erbium isotopes due to the poor ionization efficiencies associated with non-resonance ionization using incoherent radiation (mercury lamp).

Christopher A Haynam and Earl F. Worden28 have patented a three step laser isotope separation process for the separation of 167Er in 1995. They have reported two possible photoionization pathways for the laser based separation. They are 582.842 nm – 635.826 nm – 566.003 nm and 631.052 nm – 586.912 nm – 566.003 nm. Among them, the transition isotope shifts of the latter photoionization scheme have been reported to be considerably larger than the former. Therefore, this photoionization scheme has been chosen for further investigations.

Photoionization scheme

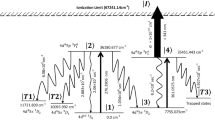

The isotope shifts of the transitions and the hyperfine structure constants of the 167Er relevant to the photoionization scheme28 have been shown in Tables 3 and 4 respectively. The relevant Rabi frequencies of transitions along with the decay rates have been shown in Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of three step photionization of erbium (not to scale). I is the intensity of laser in W/cm2. Decay rates (Γ) and Rabi frequencies (Ω) have been calculated from the excitation cross-section data provided in Ref. 28.

Results & discussion

In the three-step photoionization process under investigation, the atoms present in the 4f126s2 3H6 (0.0 cm-1) ground state are excited to the 4f115d6s2 J = 7 (15,846.549 cm-1) excited level using the first excitation laser tuned to the 631.052 nm transition. Atoms that are excited to the first excitation level are further excited to the 4f115d26s J = 8 (32,884.867 cm-1) level using a second excitation laser tuned to the 586.912 transition. These excited atoms are ionized by further exciting into an auto-ionization level present at 50,552.6 cm-1 using a third excitation laser tuned to the 566.003 nm transition. For the present work, all the lasers have been considered to be having a pulse width of 30ns, with a pulsed repetition frequency (PRF) of 10 kHz. The lasers have been considered to be co-propagating unless stated otherwise.

The density matrix elements describing the laser-atom interactions in three-step photoionization scheme have been published previously29. The density matrix elements are numerically integrated using the standard integration methods for the entire pulse duration using Gaussian temporal profiles with no temporal delay between pulses.

At the end of the laser-atom interaction, the atomic population of the auto-ionization state undergoes ionization. Therefore, population of the auto-ionization state has been considered as the ionization efficiency. From the ionization efficiency of the constituent isotopes, the degree of enrichment of the target isotope has been calculated using the equation

where, η is the ionization efficiency of an isotope and A is its fractional abundance.

Features of the ionization efficiency contours

First, ionization efficiency of natural erbium has been calculated under Doppler free conditions (i.e., ignoring the angular and velocity distribution of atoms) varying the frequency of the first and second excitation lasers for a bandwidth of 100 MHz and the intensity of 5 W/cm2 for all the lasers. For these calculations the third excitation laser is set to the 168Er resonance. The resultant two-dimensional contour is plotted in Fig. 6. The following observations can be drawn from the contour.

Two dimensional ionization efficiency contour of natural erbium under Doppler free condition. The third excitation laser is tuned to 168Er resonance. The bandwidth and intensity of all excitation lasers are 100 MHz and 5 W/cm2 respectively. The weakly observed 15/2–17/2–19/2 hyperfine pathway of 167Er isotope is marked with *. Additional resonance of 162Er isotope is marked with #.

All the resonances of even isotopes have been found at the expected positions (Table 5). Since the third excitation laser is tuned to the resonance of 168Er isotope, the ionization efficiency of other isotopes at their resonance frequencies positions in two-dimensional reference frame does not correspond to the respective abundances. The horizontal ridge of an isotope corresponds to the line spectra of the first excitation transition while the vertical ridge corresponds to the line spectra of the second excitation transition. The diagonal ridge observed arises due to the coherent two-photon excitation at all frequencies wherein the detuning of the two transitions are equal in magnitude and opposite in sign (i.e., Δ1 =—Δ2). The coherent two-photon excitation probability decreases with increase in detuning (\(\left|\Delta \right|\)).

Under the conditions described in Fig. 6, the coherent two-photon excitation is strong and extends to a few GHz. The resonance of the 168Er target isotope lies on coherent two-photon excitation ridges of the non-target even isotopes. Since the degree of coherent two-photon excitation of the constituent isotopes is determined by the laser (such as bandwidth and intensity) and atom source parameters (such as Doppler broadening) a careful control of all the system parameters is important to obtain adequate degree of enrichment and production rate.

Ionization efficiency contours of even isotopes of Er

In two dimensional reference frame, 162Er resonance appears (marked as 162Er) when the first and second excitation lasers are tuned to the (-5981 MHz, 5270 MHz) frequencies respectively. Its ionization efficiency is lower as the third excitation laser is detuned by + 398.4 MHz in its reference frame. The net detuning of this transition Δ1 + Δ2 + Δ3 is 0 MHz + 0 MHz + 398.4 MHz = + 398.4 MHz in three-photon reference frame of 162Er isotope. An unexpected additional resonance (marked as #) for 162Er has been observed at frequency positions of (-5981 MHz, 4871.6 MHz). This resonance occurs due to the direct two-photon ionization of 162Er isotope from the first excitation level. Since the third excitation is laser is detuned by + 398.4 MHz (in 162Er reference frame) the resonance occurs at the frequency of 5270 MHz – 398.4 MHz which is equal to + 4871.6 MHz. In this case, the net detuning from the resonance is Δ1 + Δ2 + Δ3 = 0 MHz – 398.4 MHz + 398.4 MHz = 0 MHz. Since the detuning in this case is smaller than the resonance at (-5981 MHz, 5270 MHz), this resonance (marked with #) is stronger. A similar but poorly resolved resonance (due to the small shift of + 187 MHz) can be for observed for 164Er isotope as well. In fact, this type of resonance can also be observed for all non-target constituent isotopes, although it cannot be resolved due to the saturation broadening and small isotope shifts associated with the third excitation transition. A detailed discussion on the lineshape contours of the three-step photoionization can be found in Ref.30.

Ionization efficiency contour of odd 167 Er isotope

A weak resonance corresponding to the 15/2–17/2–19/2 hyperfine pathway of 167Er isotope can be observed at (-1775 MHz, 348.6 MHz) frequency position (marked as * in Fig. 6). Although the natural abundance of 167Er is relatively high at 22.869%, its ionization efficiency at the frequency position corresponding to the 15/2–17/2–19/2 hyperfine pathway is quite low. This is because of the large spread of the hyperfine spectrum (4378 MHz, 4370 MHz and 5760 MHz for the three excitation transitions respectively) of 167Er. Furthermore, the most intense resonance of the 167Er isotope, associated with the 19/2–21/2–23/2 hyperfine pathway, is not observed at the (-1401.6 MHz and -53.1 MHz) frequency position (see Table 5). This cannot be explained using the two-photon reference frame presented in Table 5; instead, a three-photon reference frame must be considered. Using the spectroscopy selection rules, it is possible to formulate 135 hyperfine pathways for the three-step photoionization of 167Er (see Table 6). To further elucidate, a two-dimensional contour plot of 167Er has been plotted in Fig. 7A, where the third excitation laser is tuned to the 23/2–25/2 hyperfine transition of 167Er. The hyperfine pathways in Fig. 7 were marked as per the serial numbers in Table 6. Since the third excitation laser is tuned to the 23/2–25/2 hyperfine transition, the most intense hyperfine pathway 19/2–21/2–23/2–25/2 is distinctly observed (marked as 30 in Fig. 7A) at the expected frequency position of (-1401.6 MHz, -53.1 MHz, 815.9 MHz). It should be noted that when the excitation lasers are tuned to the (-1401.6 MHz, -53.1 MHz, 815.9 MHz) frequencies, ionization also occurs through hyperfine pathways 19/2–21/-23/2–23/2 and 19/2–21/-23/2–21/2 corresponding to the (-1401.6 MHz, -53.1 MHz, 2876.9 MHz) and (-1401.6 MHz, -53.1 MHz, 4481.5 MHz) frequency positions respectively. However, the contribution of ionization of 167Er through these channels would be rather small as third excitation laser frequency is farther away from these hyperfine pathways of the third excitation transition. Though it is expected to observe (since the third excitation laser is tuned to 23/2–25/2 hyperfine pathway) only one resonance corresponding to 19/2–21/2–23/2–25/2 hyperfine pathway (marked as 30), it is interesting to observe several other resonances (Fig. 7A). It is possible to understand the underlying reasons for the occurrence of all the resonances, nevertheless only two cases are discussed here in detail.

Two dimensional ionization efficiency contour of 167Er under Doppler free condition. The bandwidth and intensity of all excitation lasers is 100 MHz and 5 W/cm2 respectively. (A) Third excitation laser is tuned to the 23/2–25/2 hyperfine transition of 167Er (B) The third excitation laser is tuned to 168Er resonance. Hyperfine pathway numbers marked in the figure are as per Table 6.

A resonance marked as 22 in Fig. 7A is observed at the frequency position (-1431.9 MHz, 684.3 MHz) which in two dimensional frame corresponds to 13/2–15/2–17/2 hyperfine pathway. At the outset, this is entirely unexpected as the third excitation laser is tuned to 815.9 MHz corresponding to the 23/2–25/2 hyperfine pathway. On the closer look, one can observe that the (-1431.9 MHz, 684.3 MHz) in two-dimensional reference frame corresponds to the three hyperfine pathways 13/2–15/2–17/2–19/2, 13/2–15/2–17/2–17/2 and 13/2–15/2–17/2–15/2 (marked as 21–23 in Table 6). Among them the hyperfine pathway, 13/2–15/2–17/2–17/2 hyperfine pathway (marked as 22) corresponds to the frequency position the (-1431.9 MHz, 684.3 MHz, 690.8 MHz) in three-dimensional reference frame. Since the third excitation laser (at 815.9 MHz) is detuned to as little as 125 MHz, this resonance is observed. The contribution from the hyperfine pathways 21 and 23 is expected to be smaller because the larger detuning associated with the third hyperfine transition reduce the effective coupling.

Similarly, the resonance at (877.8 MHz, 3583.1 MHz) in two-dimensional reference frame (marked as 119 in Fig. 7A) corresponds to the 19/2–19/2–17/2 hyperfine pathway. In three dimensional reference frame this corresponds to 19/2–19/2–17/2–19/2, 19/2–19/2–17/2–17/2 and 19/2–19/2–17/2–15/2 hyperfine pathways (marked as 118–120 in Table 6) at frequency positions (877.8 MHz, 3583.1 MHz, -213.2 MHz), (877.8 MHz, 3583.1 MHz, 690.8 MHz) and (877.8 MHz, 3583.1 MHz, 1337.9 MHz) respectively. As discussed earlier, contribution from the hyperfine pathway 19/2–19/2–17/2–17/2 at (877.8 MHz, 3583.1 MHz, 690.8 MHz) would be much higher than other hyperfine pathways (118 and 120) due to the lower detuning associated with of the third step excitation.

Apart from the relative intensities of the hyperfine transitions, the contribution from the different hyperfine pathways to the ionization of 167Er varies with variation in all the laser and atom source parameters. Thus, when the third excitation laser is tuned to the 168Er resonance the relative contribution of all the 135 hyperfine pathways towards the ionization of 167Er varies (Fig. 7B). In this, case the hyperfine pathway at (-122.9 MHz, 348.6 MHz) in two-dimensional reference frame (marked as 76 in Fig. 7B) corresponds to the hyperfine pathways 17/2–17/2–19/2–21/2, 17/2–17/2–19/2–19/2 and 17/2–17/2–19/2–17/2 (marked as 76–78 in Table 6) at frequency positions (-122.9 MHz, 348.6 MHz, 111.7 MHz), (-122.9 MHz, 348.6 MHz, 1332.6 MHz) and (-122.9 MHz, 348.6 MHz, 2236.6 MHz) respectively. Among them the contribution by the 17/2–17/2–19/2–21/2 at (-122.9 MHz, 348.6 MHz, 111.7 MHz) frequency position would be the highest due to higher intensity and lower detuning corresponding to the hyperfine pathway of the third excitation transition (19/2–21/2).

It is also important to note that when the excitation lasers are tuned to 168Er, the resonance of 168Er isotope lies on the vertical ridge (step-wise excitation of the second excitation transition) of hyperfine pathways (marked 76–78 in Table 6) of 167Er isotope. This is in contrast to the case of even isotopes (Fig. 6), wherein the resonance of 168Er isotope lies on the diagonal ridges of even isotopes (arising due to coherent two-photon excitation). Therefore, the ionization of 167Er can be somewhat controlled by controlling the intensity and bandwidth of the second excitation laser. On the other hand, to reduce the ionization of non-target even isotopes, one needs to control the intensity and bandwidth of all excitation lasers.

It is not possible to qualitatively assess the effect of intensity and bandwidth of all the three excitation lasers on the ionization efficiency of target and non-target isotopes. For quantitative assessments, one needs to obtain ionization efficiencies of all constituent isotopes varying the system parameters through numerical integration of coupled differential equations29.

A series of calculations have been conducted by varying the intensities of all three excitation lasers across different bandwidths, all under Doppler-free conditions. The results have been tabulated in Table 7. The table shows that it is possible to enrich the 168Er isotope to up to 95% for all laser bandwidths up to 750 MHz. Therefore, laser bandwidths need to be controlled to ≤ 750 MHz. Interestingly, the content of 167Er decreased with an increase in the excitation laser’s bandwidth. This can be attributed to the reduction in the intensity of the second excitation laser (please refer to the earlier discussion in this section).

Effect of Doppler broadening

So far, the Doppler broadening of the atomic ensemble has been ignored for the computations. However, in the laser isotope separation process, the atomic ensemble exhibits Doppler broadening due to the velocity distribution of the atoms.

To include Doppler broadening of the atomic ensemble, atomic flux-velocity distribution is taken as

where, α is the most probable velocity; for the present calculations, the integration is carried out up to 4α, at which the relative flux had dropped to the value of ~ 10–7 of the maximum.

At 1200 ˚C, the erbium atoms have a most probable velocity of 381.7 m/sec. When these atoms traverse with an angle of “θ” to the laser propagation axis, the Doppler shift of the resonance can be expressed by the equation

where v is the velocity of the atom (m/sec) and λ is the wavelength of the transition (nm) and θ is the divergence angle of the atom relative to the laser propagation axis. When an atom has a divergence angle of 10˚ with reference to the laser propagation axis, the Doppler shift of the transitions is 105.1 MHz, 113.0 MHz, 117.2 MHz. Even when all the co-propagating lasers are tuned to resonance for each excitation step, the net detuning caused by the Doppler shift totals 335.3 MHz, which is the sum of 105.1 MHz, 113.0 MHz, and 117.2 MHz. If the bandwidth of all the excitation lasers is 100 MHz or greater, the atoms will be excited and ionized, though with reduced efficiency. In a practical laser isotope separation process, the atomic ensemble exhibits a distribution of velocities Therefore, to account for Doppler broadening, ionization efficiency calculations have been performed for a range of angular divergences of the atomic ensemble. The results are summarized in Table 8, which includes the degree of enrichment for each isotope and the ionization efficiency of the target isotope. It can be observed that a degree of enrichment greater than 95% can be achieved for all laser bandwidths up to 750 MHz when the atomic ensemble’s full angular divergence is 30° or less. A laser bandwidth of 500 MHz and a full angle divergence of 30° can be considered optimal for the laser isotope separation process. Under these conditions the degree of enrichment of 168Er is > 96% and the ionization efficiency is 0.2.

Choice of co-propagating vs counter-propagating laser beams

In laser isotope separation, employing co-propagating laser beams ensures simpler and optimal overlap throughout the interaction zone, thereby maximizing the effectiveness of the separation process. While co-propagating beams provide the benefit of effective overlap, laser isotope separation can also be achieved using counter-propagating laser configuration. Since the resonance of the 168Er target isotope lies on the coherent two-photon excitation lines of non-target even isotopes (Fig. 6), the ionization efficiency of target and non-target isotopes varies with co- and counter-propagating laser beam configurations. Consequently, calculations have been conducted to determine the ionization efficiency of the 168Er isotope and the enrichment levels of all constituent isotopes across all four possible configurations (see Table 9). Data from Table 9 suggests that the direction of laser-3 propagation (relative to laser-1 or laser-2) does not influence both degree of enrichment and the ionization efficiency of the constituent isotopes. However, Table 9 also shows that when laser-2 propagates in the opposite direction (counter-propagating) relative to laser-1, the degree of enrichment of the target isotope 168Er decreases by 1%. This decrease is attributed to the increased ionization efficiency of neighbouring non-target even isotopes, particularly 166Er and 170Er. When laser-2 counter-propagates (relative to laser-1), it cancels out the velocity-induced detunings in the two-photon reference frame, resulting in higher ionization efficiency of non-target isotopes. Therefore, the co-propagating configuration (↑↑↑) is preferred for the laser isotope separation process.

Charge-exchange collisions

Charge exchange collisions significantly influence the effectiveness of the laser isotope separation process. To achieve a high production rate of the enriched isotope, it is essential to operate the atomic ensemble at the highest feasible atomic number density. However, as the number density increases, the charge-exchange collisions also increase, which negatively impacts the degree of enrichment. The probability of charge-exchange collisions can be calculated using the expression.

Where, σ is the resonant charge exchange cross-section (cm2), d is the distance traversed by photoions prior to collection at the ion collector (cm) and N is the number density of the atoms (atoms / cm3).

Resonant charge exchange cross-section can be calculated using the following formula31

where v is the velocity of the ion in cm/sec and IP is the ionization potential of the element in eV.

For the most probable atomic velocity of 381.7 m/sec for erbium at 1200° C, the resonant charge exchange cross-section has been calculated to be 4.2 × 10–14 cm2, which is in reasonable agreement with the value of 2.8 × 10–14 cm2 reported by Smirnov et al.32.

A series of calculations of degree of enrichment have been carried out varying the number density of the atoms in the laser-atom interaction region diameter of 5 cm and the results are plotted in Fig. 8. It can be observed from Fig. 8 that a degree of enrichment of > 90% for 168Er can be achieved by controlling the number density to ≤ 7 × 1011 atoms/cm3; while a degree of enrichment of 80% for 168Er can be achieved at the number density of 2 × 1012 atoms/cm3. From the data in Fig. 8, the appropriate number density value can be chosen based on the desired degree of enrichment for the target isotope. Although 167Er is adjacent in mass to the target isotope, its degree of enrichment is lower than that of 166Er. This is attributed to the broader hyperfine spectrum of 167Er.

Effect of charge-exchange collisions on the degree of enrichment of erbium isotopes. The distance traversed by photoions prior to collection at the ion collector is taken as 5 cm. The bandwidth of all excitation lasers is 500 MHz. The intensities of the excitation lasers are 800 W/cm2, 1000 W/cm2 and 2400 W/cm2 respectively. All the excitation lasers are tuned to 168Er resonance.

Production rate

Production rates can be calculated using the following equation

where b is the laser beam diameter (cm), p is the fractional population of the ground level, l is the length of the laser-atom interaction region (cm), d is the number density of atoms in the interaction region (atoms/ cm3), A is the fractional abundance of the target isotope, f is the fractional flux (flux relative to the flux of unhindered atomic beam), η is the ionization efficiency (derived from the density matrix calculations), i is the irradiation probability, n is the number of passes of the laser beam through the laser-atom interaction region, M is the atomic mass of the target isotope (AMU), NA is the Avogadro number (6.02214076 × 1023) and PRF is the pulse repetition frequency of the lasers (Hz).

For the values of b = 5 cm, p = 0.992, l = 100 cm, d = 7 × 1011 atoms/cm3, A = 0.26978, f = 1, η = 0.20, i = 1, n = 1, M = 168, PRF = 10 kHz, the production rate has been calculated to be 740 mg/ hour (or 18 g/day). A summary of the optimum system parameters for the separation of 168Er isotope is shown in Table 10.

Table 11 compares the degree of enrichment and the production rates of precursor isotopes from previous studies with those from the current work. The production rate of the precursor isotope with the current method is one to two orders of magnitude higher than that of previously reported methods. Therefore, it is envisaged that the enriched isotopes produced by this method will meet the current demand for the enriched isotope precursors.

Irradiation of enriched isotope mixture

In this section, the utility of enriched 168Er (produced through the AVLIS process) for medical applications has been studied for its suitability to medical application. When the natural erbium is irradiated in a nuclear reactor, after chemical separation erbium, it consists of five erbium radioisotopes namely., 163Er, 165Er, 169Er, 171Er and 172Er. (Fig. 1). On the other hand, when the enriched erbium is irradiated, after chemical separation, it consists of only three 169Er, 171Er and 172Er radioisotopes. The production efficiency erbium radioisotopes during the irradiation in low, medium and high-flux reactors is shown in Fig. 9. The separated radioisotopes of erbium produce decay chain nuclides which are shown in Fig. 10.

Medical fraternity desires the medical isotope to be produced with highest radioisotopic purity (not to be confused with isotopic purity) possible for the optimal control of the dose to the patient. The radioisotopic purity (Ri) of an isotope “i” can be calculated using the expression:

where Si is the carrier free specific activity of the radioisotope “i” (Bq/g), fi is the relative fractional abundance of the isotope present in the isotope mixture, n is the number of radioisotopes in the isotope mixture.

Since the radioisotopes of the isotopic mixture have varying half-lives the radioisotopic purity of the isotope mixture varies with time. The radioisotopic purity of the 169Er produced from the enriched erbium increases from 96% to 99.5% within 24 h which is adequate for the application intended (Fig. 11). Using the enriched 168Er isotope obtained from the laser isotope separation process, irradiation in low, medium, and high flux reactors can produce 180, 1800, and 18,000 doses per day (each with an activity of 7.4 GBq) respectively.

Conclusions

This present study investigates a three-step laser isotope separation method for enriching 168Er using 631.052 nm – 586.912 nm – 566.003 nm three-step photoionization scheme. The lineshape contours observed in three-step photoionization process have been investigated in detail. The effect of bandwidth and intensity of the excitation lasers, Doppler broadening of atomic ensemble on the degree of enrichment and the production rate have been systematically studied. It has been shown that, unlike the enrichment processes for other lanthanides such as 176Lu and 176Yb isotopes, enriching 168Er requires a relatively simpler experimental configuration.

Based on the above investigations, an optimum system configuration for the efficient laser isotope separation of 168Er has been derived. With the derived system configuration, it is possible to produce 18 g/day of 90% enriched 168Er. Using the enriched 168Er isotope obtained from the laser isotope separation process, irradiation in low, medium, and high flux reactors can produce 180, 1800, and 18,000 doses per day (each with an activity of 7.4 GBq) respectively. After 24 h of irradiation and chemical separation, the radioisotopic purity of the medical isotope reaches to > 99% making it suitable for the medical applications. The current method is also free from isobaric impurities, which can otherwise affect the performance of the medical isotope.

From an application standpoint, enriching the 168Er isotope offers significant advantages compared to 176Lu and 176Yb. This is the first ever study on the laser isotope separation of 168Er isotope, holds promise for filling the growing demand–supply gap for the radioisotope precursors in the coming years.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dash A, Raghavan M, Pillai A & Knapp Jr. FF Production of 177Lu for targeted radionuclide therapy: available options. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 49, 85–107 (2015).

Sankari, M. Kiran Kumar PV & Suryanarayana MV Study of line shapes in the selective ionization of Yb176 isotope in a two-step resonance, three-step ionization scheme. Journal of the Optical Society of America 25B, 1820–1828 (2008).

Suryanarayana MV Isotope selective three-step photoionization of 176Lu. Journal of the Optical Society of America 38B, 353–370 (2021).

Suryanarayana MV & Sankari M Laser isotope separation of 176Lu through off-the-shelf lasers. Scientific Reports 11, 18292 (2021).

Suryanarayana, M. V. Isotope separation of 176Lu a precursor to 177Lu medical isotope using broadband lasers. Scientific Reports 11, 6118 (2021).

Suryanarayana MV & Sankari M Isotope selective three-step photoionization of 176Yb. Journal of the Optical Society of America 38B, 3331–3339 (2021).

Suryanarayana, M. V. Isotope selective three-step photoionization of 177Lu. Journal of the Optical Society of America 39B, 2502–2521 (2022).

Suryanarayana MV & Sankari M Isotope selective three-step photoionization of 174Yb. Journal of the Optical Society of America 40B, 53–62(2023).

Sankari M & Suryanarayana MV Theoretical investigations on the laser isotope separation of 175Yb for medical applications. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 209, 111328 (2024).

Park, H. Kwon D -H, Cha Y, Nam A, Kim T -S, Han J, Rhee Y, Jeong D -Y & Kim C -J Laser isotope separation of 176Yb for medical applications. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 49, 382–386 (2006).

Park, H. Kwon D -H, Cha Y, Nam A, Kim T -S, Han J, Ko K -H, Jeong D -Y & Kim C-J Stable isotope production of 168Yb and 176Yb for industrial and medical applications. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 45, 111–116 (2008).

Andreev, O. I., Derzhiev, V. I., Dyakin, V. M. & Egorov, A. G. Mikhal’tsov L A, Tarasov V A, Tolkachev A I, Toporov Y G, Chaushanskii S A & Yakovlenko S I Production of a highly enriched Yb isotope in weight amounts by the atomic-vapour laser isotope separation method. Quantum Electron. 36, 84–89 (2006).

D’yachkov A B, Kovalevich S K, Labozin A V, Labozin V P, Mironov S M, Panchenko V Y, Firsov V A, Tsvetkov G O & Shatalova G G Selective photoionisation of lutetium isotopes. Quantum Electron. 42, 953–956 (2012).

D’yachkov A B, Firsov V A, Gorkunov A A, Labozin A V, Mironov S M, Panchenko V Y, Semenov A N, Shatalovaa G G & Tsvetkov G O Photoionization spectroscopy for laser extraction of the radioactive isotope 177Lu. Appl. Phys. 121B, 425–431 (2015).

D’yachkov A B, Gorkunov A A, Labozin A V, Mironov S M, Panchenko V Y, Firsov V A & Tsvetkov G O Effect of amplified spontaneous emission on selectivity of laser photoionisation of the 177Lu radioisotope. Quantum Electron. 46, 574–577 (2016).

D’yachkov A B, Gorkunov A A, Labozin A V, Mironov S M, Tsvetkov G O, Panchenko V Y & Firsov V A Study of a selective photoionization scheme of 177Lu. Opt. Spectrosc. 125, 839–844 (2018).

D’yachkov A B, Gorkunov A A, Labozin A V, Mironov S M, Panchenko V Y, Firsov V A & Tsvetkov G O Development of a laser system of the laboratory AVLIS complex for producing isotopes and radionuclides. Quantum Electron. 48, 75–81 (2018).

Ageeva, I. V. D’yachkov A B, Gorkunov A A, Labozin A V, Mironov S M, Panchenko V Y, Firsov V A, Tsvetkov G O * Tsvetkov G O Laser photoionisation selectivity of 177Lu radionuclide for medical applications. Quantum Electron. 49, 832–838 (2019).

D’yachkov A B, Gorkunov A A, Labozin A V, Makoveeva K A, Mironov S M, Panchenko V Y, Firsov V A & Tsvetkov G O A study of laser photoionization of 177mLu nuclear isomer. Opt. Spectrosc. 128, 6–11 (2020).

D’yachkov A B, Gorkunov A A, Labozin A V, Mironov S M, Panchenko V Y, Firsov V A & Tsvetkov G O A study of the kinetic parameters of Lu laser photoionization scheme. Opt. Spectrosc. 128, 289–296 (2020).

Formento-Cavaier R, Köster U, Crepieux B, Gadelshin VM, Haddad F, Stora T & Wendt K Very high specific activity erbium 169Er production for potential receptor-targeted radiotherapy. Nuclear Inst. and Methods in Physics Research 463B, 468–471 (2020).

Zeynep Talip, Francesca Borgna, Cristina Müller, Jiri Ulrich, Charlotte Duchemin, Joao P. Ramos, Thierry Stora, Ulli Köster, Youcef Nedjadi, Vadim Gadelshin, Valentin N. Fedosseev, Frederic Juget, Claude Bailat, Adelheid Fankhauser, Shane G. Wilkins, Laura Lambert, Bruce Marsh, Dmitry Fedorov, Eric Chevallay, Pascal Fernier, Roger Schibli, Nicholas P. van der Meulen Production of Mass-Separated Erbium-169 Towards the First Preclinical in vitro Investigations. Frontiers in Medicine 8, 643175 (2021).

Bradley Patton and Sharon Robinson A Summary of Actinide Enrichment Technologies and Capability Gaps. ORNL Report No. ORNL/TM-2016/661 (2017).

Chakravarty, R. & Chakraborty, S. Viju Chirayil & Ashutosh Dash Reactor production and electrochemical purification of 169Er: A potential step forward for its utilization in in vivo therapeutic applications. Nuclear Medicine and Biology 41, 163–170 (2014).

E. F. Worden, R. W. Solarz, J. A. Paisner & J. G. Conway First ionization potentials of lanthanides by laser spectroscopy. J. Opt. Soc. America 68, 52–61 (1978).

N. V. Karlov, B. B. Krynetskii, V. A. Mishin & A. M. Prokhorov Laser isotope separation of rare earth elements. Applied Optics 17, 856–862 (1978).

N. V. Karlov, B. B. Krynetskii & V. A. Mishin Isotope separation of the lanthanoid group elements by the method of two-step selective photoionization. Journal of Soviet Laser Research 2, 123 – 132 (1981).

Christopher A Haynam & Earl F. Worden Laser isotope separation of erbium and other isotopes US Patent No. US5443702A, 1995.

M. V. Suryanarayana & M. Sankari Isotope selective three-step photoionization of 177Lu Journal of the Optical Society of America 39B, 2502–2521 (2022).

MV Suryanarayana & M Sankari Laser enrichment of 62Ni isotope for betavoltaic devices. Journal of the Optical Society of America 41B, 2155–2164 (2024)

Sakabe, S. & Izawa, Y Simple formula for the cross sections of resonant charge transfer between atoms and their positive ions at low impact velocity. Phys. Rev. 45A, 2086–2088 (1992).

Smirnov B M Tables for cross sections of the resonant charge exchange process Phys. Scr. 61, 595–602 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of Computational Analysis Division, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Visakhapatnam, for providing the Super Computer Facility that facilitated this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the work reported in this manuscript was conducted solely by MV Suryanarayana, with no potential contributors having been overlooked.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suryanarayana, M.V. Laser isotope enrichment of 168Er. Sci Rep 15, 10543 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80936-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80936-8