Abstract

In recent years, Silicene has attracted great interest in various fields but does not fit well in the field of thermoelectrics due to the absence of electronic band gap. Nevertheless, hydrogenation of silicene (SiH) delocalize the free electrons and induces gap widening (2.19 eV), but its thermoelectric performance is still limited due to the larger band gap. Thermoelectric performance can be effectively improved using strain engineering, which allows modulation of crystal as well as electronic energy levels of a material. We studied the effect of biaxial tensile strain on structure, stability and thermoelectric properties of SiH monolayer. Taking clue regarding the stability from phonon dispersion, tensile strain upto 14% is incorporated and results are discussed. The distortion of crystal structure with strain manipulates the characteristics of electronic band structure such that there is an indirect to direct band gap transition along with decrease in band gap, effective mass and relaxation time of carriers. As a result, the Seebeck coefficient falls and attains minimum value at 14% strain while electrical conductivity and electronic thermal conductivity shows increasing trend and maximize at 14% strain. Another crucial consequence of strain is that tensile strain led to a considerable decrease in lattice thermal conductivity. At a strain of 14%, the lattice thermal conductivity at 700 K (0.28) decreased by approximately 43% compared to its unstrained counterpart (0.49 K), which is highly beneficial for achieving high ZT. To assess the efficiency of thermoelectric conversion, the ZT is computed, revealing an increase from 1.66 in the unstrained state to 2.83 at a strain of 14% and a temperature of 700 K. The calculations unveil a nearly twofold increase in ZT with the implementation of strain engineering, underscoring its effectiveness in augmenting the efficiency of thermoelectric devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To recover useless energy lost by different energy sources, people are seeking for efficient energy recovery techniques1. Many operations in both industries and daily life involve actions where a significant amount of energy is lost to the environment2. In the field of thermal management and energy harvesting, thermoelectric materials have attracted researchers as these materials assists in recovering the lost energy by utilising the Seebeck effect, the fundamental idea underpinning the conversion of heat into electricity3. The dimensionless figure of merit ZT = \(\frac{{S2\upsigma T}}{k}\), which includes Seebeck coefficient (S), electrical conductivity (\(\sigma\)) and total thermal conductivity (k = kl + ke) accurately quantify the efficiency of a thermoelectric material4. The parameters involved in ZT are inter-linked and challenging to individually adjust because of interdependency of S, \(\sigma\) and k, caused by carrier concentration. However, new ideas or techniques continue to enhance the thermoelectric performance of materials5,6. Recently, a number of typical approaches with the intention of enhancing thermoelectric performance have been put forth7. Examples include enhancing electrical characteristics by optimizing carrier concentration8,9 and band structure engineering10,11,12 or reducing lattice thermal conductivity by phonon engineering13,14, which can be done through creating defects, rattling bonds and nano-structuring15,16,17. Also, people are looking for novel compounds with naturally low thermal conductivity.

While carbon readily form sp2 hybrid orbitals, which is not achievable for other elements like Si, Ge, Sn, and Pb due to the inadequate p-type overlap between neighboring p orbitals at the typical distances imposed by normal s bonding. Consequently, the existence of independent graphene-like single layer for Si, Ge, Sn, and Pb is highly improbable. The poor p-type overlap restricts the formation of similar structures in these elements. In recent years, there have been theoretical predictions regarding the electronic and structural properties of silicene. Notably, Cahangirov et al. has reported that silicon and germanium have the potential to showcase stable 2D honeycomb structures with slight corrugation, proving more stability than their equivalent planar counterparts18. The three s–p hybridized orbitals form sigma bonds with nearest neighours in a plane and the out of plane pz orbitals of neighboring atoms form weak π bonding, leading to the delocalized electrons. This characteristic cause electrons in silicene to behave similarly to mass-less Dirac fermions, akin to the behavior observed in graphene. Again, the applications of these monolayers are limited due to their semi-metallic nature. Indeed, manipulating the localization of electrons involved in π bonding can significantly affect the electrical characteristics of a material. If these electrons can be localized, it becomes possible to open up a band gap, transforming the material from a metallic to a semiconducting phase. Researchers have experimented with various elements deposited on the surface of monolayers, observing changes in the band gap and other properties19,20. This exploration is crucial for tailoring the electronic characteristics of materials and expanding their potential applications in semiconductor devices. Jugdersuren et al. successfully fabricated single and multilayered hydrogenated silicene (SiH) on polycrystalline Ag films using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD)21. The stability of designed SiH monolayer was experimentally tested using various techniques. Theoretical research has been conducted to anticipate the thermoelectric characteristics of monolayers composed of silicon with different elements such as SiX (X = N, P, As, Sb)22. The findings indicate that monolayers based on silicon hold significant promise for use in thermoelectric applications. Khand et al. methodically investigated the electronic characteristics and the alignment of energy bands of heterojunction formed by combining single layers of 2D Boron Phosphide (BP) and Silicane (SiH). The BP/SiH heterojunction remains structurally and mechanically sound in its fundamental state23. Additionally, 2D materials with a wide band-gap have drawn a lot of interest such as GeI2, GeX (X = S, Se, Te), SiH, GeH, e.t.c with exceptional Seebeck coefficient and thermoelectric performance24,25,26,27. Therefore, employing 2D materials for thermoelectric devices represents an optimal approach to enhance thermoelectric efficiency28,29. In a recent study, we have documented the thermoelectric behavior of SiH monolayer, uncovering its remarkable characteristics such as a notably high Seebeck coefficient and a substantial power factor26. The value of ZeT was found to be 2.18 at ambient temperature26. Chemical, thermal, and dynamical stability served as proof of its experimental realisation. On including lattice part of thermal conductivity, the value of ZeT will fall. Therefore, improvisation of SiH monolayer is needed for better thermoelectric performance.

Effect of strain on the thermoelectric performance of 2D materials has been recognized as a promising avenue to optimize their energy conversion capabilities30,31. Strain engineering offers a powerful tool to tailor the electronic band structure32,33 and phonon scattering in these materials34,35, which are crucial factors governing their thermoelectric properties. By exerting mechanical stress on a 2D material, one can effectively modulate the transport characteristics of charge and heat carriers, thereby significantly impacting the overall thermoelectric efficiency. To realise its full potential for practical thermoelectric applications, proper strain management and understanding of material behaviour are required. Researchers are continuing to investigate strain engineering as a useful tool in the search for more efficient thermoelectric materials. Lately, the tuning of physical properties of 2D materials via strain engineering has been validated as an uncomplicated yet powerful strategy which can be done experimentally by micro-mechanical distortion/bending or by lattice mismatch between substrate and nanosheet36. Computational studies have explored the thermoelectric characteristics of SnSe monolayer subjected to both compressive and tensile strains, which shows a threefold increase in its ZT at 600 K37. The improvisation of thermoelectric performance via strain is also supported by a study done by Le et al.38. They showed that the combined variation of various thermoelectric parameters of ZrS2 monolayer with strain leads to a maximum ZT value of 2.4 at 6% tensile strain, which is 4.3 times higher than pristine monolayer. Their findings indicate that manipulating various thermoelectric parameters in ZrS2 monolayer when subjected to strain results in a maximum ZT value of 2.4, which is 4.3 times greater than that of the pristine monolayer.

From this discussion, we concluded that the electronic transport properties and hence ZT are particularly sensitive to lattice constant of a material which can be modulated using strain engineering. The band tuning enhances the electronic transport properties while phonon distortion supresses lattice thermal conductivity resulting in overall improvement in thermoelectric behaviour of a material. It is therefore intriguing to explore the influence of external strain on thermoelectric response of SiH monolayer. In this work, we have proven that biaxial tensile strain considerably enhances the thermoelectric performance of SiH monolayer. Therefore, this research offers an excellent material candidate for investigating the impact of strain on its thermoelectric transport characteristics, potentially enhancing the design of related experiments.

Computational methodology

Structural and electronic simulations are executed using Quantum Espresso package utilizing density functional theory (DFT) approach39. Projector Augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials for electron–ion interactions are used with cutoff for wavefunction and charge density of 80 Ry and 750 Ry, respectively. Generalized gradient approximation (GGA) using Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) is employed for exchange and correlation interaction between electrons40. A vacuum space of 23.72 Å is used between neighboring layers along z-axis to avoid interlayer interactions. The structure is fully relaxed using 15\(\times\)15\(\times\)1 Monkhorst–Pack k-points grid with energy convergence criteria of 10–6 eV and Hellman–Feynman convergence threshold of 10–5 eVÅ−141. A biaxial in-plane tensile strain, ranging from 0% to + 14%, is applied symmetrically in x–y plane.

The BoltzTrap code is utilized for the computation of transport parameters like S, \(\sigma\) and κe by employing the Boltzmann transport equations (BTE) based on calculated electronic structure42. The dependency of these parameters on energy band structure is provided by BTE43:

and

where α, β are cartesian indices, \(f_{0 }\) is Fermi-distribution function44. The κe and σ are coupled by Wiedemann–Franz law given by κe = L\({\upsigma }\)T, where L is the Lorentz number45.

The code incorporates built-in approximation where S remains unaffected by the relaxation time (\({\uptau }\)) of carriers, while σ and κe display a linear dependency on it46. The scattering of electrons by different means inside crystal is governed by Matthiessen’s rule, that is \({\uptau }^{ - 1}\) = \(\sum_{i} {\uptau }_{i}^{ - 1}\)47. Among different scattering sources, the temperature dependent (electron–phonon) scattering is assumed to be dominant in this work and is calculated by deformation energy method in order to get the exact variation of transport parameters with temperature. The utilization of deformation energy method is integral in calculating both carrier mobility and relaxation time and is defined as48,49:

where \(\mu\), \(C_{\beta }^{2D }\) and \(E_{\beta }^{*}\), respectively, are mobility, elastic constant and deformation potential constant. These values are calculated by quadratic fit of total energy and linear fit of shift in band extremum with respect to deformed lattice constants. Also, as \(m_{d}^{*} = \sqrt {m_{x}^{*} \times m_{y}^{*} }\) is an average effective mass and \(m^{*} = \frac{{\hbar^{2} }}{{{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${\partial^{2} E}$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial^{2} E} {\partial k^{2} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${\partial k^{2} }$}}}}\) is effective mass of carrier50,51. For proper convergence of the transport parameters, a dense k-mesh is employed.

The lattice thermal conductivity of SiH monolayers is determined using the Sheng BTE package, employing a self-consistent iterative algorithm52. The Quantum Espresso code is utilized to compute phonon dispersion and corresponding second-order interatomic force constants (IFCs), while the third-order anharmonic force constants, which account for inelastic phonon scattering (Umklapp processes), are calculated using the thirdorder.py script53,54. For these calculations, 4 × 4 × 1 supercells are constructed, incorporating interactions up to the third nearest neighbors.

Results and discussions

Effect of strain on crystal and electronic structure

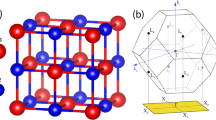

Silicene crystallize in low buckled hexagonal structure with space group of P3m1. The in-plane strong covalent bonding between sp2 orbitals involve \(\sigma\) bonds while out-of-plane weak bonding between pz orbitals involve π bonds. The later results in delocalization of electrons and is responsible for its semi-metallic nature. Thus, Silicene does not fit well in the category of thermoelectric materials. An effort had been made to localize the out-of-plane free electrons and open up the bandgap by deposition of hydrogen atoms symmetrically on both sides of Silicene monolayer to get hydrogenated Silicene (SiH). This opens up the bandgap of 2.19 eV, which is much higher than the optimum bandgap of a potential thermoelectric material (10kBT). Thus, we have commenced strain engineering in order to reduce the bandgap and enhance thermoelectric performance of SiH monolayer. Starting with optimization of pristine SiH structure, we obtained lattice constants a = b = 3.89 Å, which are in consistency with the experimental data55. Figure 1 demonstrates that the structure consists of an atomic sublayers of Si atoms sandwiched between two sublayers of H atoms. The applied biaxial tensile strain is simulated by \(\varepsilon = \left( {a - a_{o} } \right)/a_{o} \times 100\), where \(a\) is lattice constant under biaxial tensile strain and \(a_{o}\) is equilibrium lattice constant. Under the action of an external strain ranging from 0% to + 14%, the structure gets deformed such that the in-plane bond length (d(Si–Si)) increases from ~ 2.35 Å to ~ 2.83 Å, which is obviously due to stretching of bonds and an increase in lattice constants. The large change in bond length manifest that the bonding is sensitive to external strain. Meanwhile, the out-of-plane bond length (d(Si–H)) remains intact while the bond angle (θ(Si–Si-H)) decreases from ~ 107° to ~ 104°. Although the out-of-plane bond length remains invariant, the decrease in bond angle slightly tilts the hydrogen atoms inwards which results in a decrease in layer thickness. Because tensile strain pushes atoms away from one another, the interaction between atoms weakens and there is a softening of bonding character between them. As a result, elastic constant (\(C_{\beta }^{2D }\)) decreases with an increase in strain. These modifications suggest that the crystal structure of SiH monolayer tends to stabilize in a state where out-of-plane hydrogen atoms prefer to shrink towards the plane under external strain. Table 2 lists the values of \(C_{\beta }^{2D }\) of monolayer at different strains. Thermal stability of pristine SiH monolayer has already been verified using MD simulations in our pervious study and total energy fluctuations with time is presented in Fig. 1d26. The examination of fluctuations in total energy over time validates the thermal stability of the monolayer at room temperature.

Demonstration of crystal structure of SiH monolayer with (a) top view (b) side view. Silicon and hydrogen atoms are respectively highlighted by blue and red colors. (c) Variation of layer thickness with applied strain. (d) Molecular Dynamics simulation of SiH monolayer showing energy fluctuations with respect to time at room temperature.

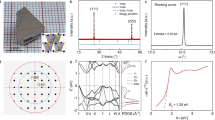

Figure 2a, b and c, d demonstrates the electron localization function of pristine silicene (Si) and hydrogenated silicene (SiH), respectively. The in-plane \(\sigma\) bonding between sp2 hybridized orbitals is shown by high electron density (with elf value of 1) between silicon atoms. The electron density is located symmetrically between silicon atoms, indicating strong in-plane non-polar covalent bonding. The out-of-plane weak π bonding between delocalized pz-orbitals of Si atoms (with elf value of 0.5) is shown in Fig. 2b. The buckling phenomenon in silicene causes the pz-orbitals to extend outward, resulting in the creation of an asymmetric and intricately shaped π-bonds and is the main cause of its high anharmonicity. On hydrogenation of silicene, the in-plane \(\sigma\) bonds between silicon atoms become more diffuse due to the interaction of silicon atoms with hydrogen ones. This interaction also affects lattice parameters of SiH monolayer. The out-of-plane pz-orbitals of silicon atoms overlap with s-orbitals of hydrogen atoms to form a sp hybrid lobe of \(\sigma\) bond. The side view of the SiH monolayer, as depicted in Fig. 2d, reveals the presence of this particular lobe. The substantial electron density between silicon and hydrogen atoms (with ELF value of 1) emphasizes the robust covalent bond between them. This results in the localizaton of pz-orbital electrons of silicon atoms and induces the electronic band-gap in SiH monolayer.

The pristine monolayer is a wide bandgap semiconductor having band-gap of 2.19 eV with valence band and conduction band extremum locating at Γ and M high symmetry points of Brillouin zone, justifying its indirect band-gap semiconducting nature. The applied strain modifies the nature of band structure as well as magnitude of band gap. There occurs a band transformation from indirect to direct band gap semiconducting material at 4% strain by shifting the conduction band minima (CBM) from M point (state II) to Γ point (state I) while preserving the position of valence band maxima (VBM) (state III). Furthermore, the monolayer holds direct band-gap nature upto + 14% of strain as shown from Fig. 3. The valence band maxima are nearly parabolic close to fermi level and possess degenerate heavy and light hole bands. The conduction band has two minima at points I and II with small energy difference in between. State I lie lower than state II and is nearly flat while state II shows parabolic behaviour. The parabolic dispersion suggests nearly free behaviour of charges with delocalised states while flat dispersion signifies strong localization of electronic states56. As delocalized states are more influenced by external strain as compared to localized states, state I shifts downwards much faster than state II when strain increases. This explains switching of band structure from indirect to direct band gap nature and lowering of band gap value from 2.16 eV to 0.21 eV. Meanwhile, external strain influences spin–orbit coupling of atoms and removes degeneracy of valence band by splitting heavy hole and light hole bands. Additionally, with an increase in strain, the bands become more and more dispersive near Fermi level which reduces band effective mass of carriers, causing an increase in carrier mobility. The dispersion of band extremum near Fermi level along Γ-M and Γ-K directions are almost isotropic at all strain percentages. This will result in nearly identical behaviour of electronic characteristics of the monolayer along different directions. The transport properties of SiH monolayer will be significantly impacted by the strain tuned band structure since these characteristics highly depend on electronic structure. The band-gap variation can also be justified from density of states (DOS) plots as shown in Fig. 3. The projected density of states reveals that, across all strain conditions, the involvement of distinct atomic orbitals in the valence and conduction bands remains consistent. In the valence band, the primary influence comes from the overlap of p and s-orbitals of Si and H atoms, respectively, with a negligible involvement originating from s-orbitals of Si atoms. Conversely, the conduction band is generated by the overlap of s and p-orbitals of Si atoms, with a limited contribution from H atoms.

Effect of strain on stability and thermal transport

The chemical stability of SiH monolayer at different strain levels is affirmed through the analysis of its formation and cohesive energies. The calculation of formation energy is performed using the given equation57:

here E(SiH) is the energy of SiH monolayer, whereas E(H) and E(Si) are the energies of H and Si atoms in their respective bulk structures. On the other hand, the cohesive energy (Ec) is defined as:

Here, the total energy of H and Si atoms in their free structures are represented by E(Si) and E(H). Upto 14% strains, both Ef and Ec remains negative but their magnitude decreases with an increase in strain as presented in Table 1. Negative values of both Ef and Ec at all strains upto 14% are in favor of chemical stability but their decreasing trend with increasing strain indicates weakening of bonds between atoms. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that as strain levels increase in SiH monolayer, there is a noticeable decrease in elastic constant. This reduction is associated with a corresponding decrease in vibrational frequency and mean free path of phonons. Consequently, this results in a decrease in lattice thermal conductivity, which is an expected characteristic in high-performance thermoelectric materials.

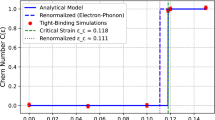

The modulation of phonon spectrum of SiH monolayer by the application of strain is demonstrated in Fig. 5. No imaginary phonon frequency at any point on Brillouin zone is observed upto 14% strain, but at 16%, which justifies its dynamical stability only upto 14% of strain. The highest frequency LO and TO branches of SiH monolayer are degenerate at Γ point which justifies covalent bonding character between the atoms. In most of the 2D materials, the out-of-plane ZA mode shows more contribution towards lattice thermal conductivity as compared to in-plane longitudinal acoustic (LA) and transversal acoustic (TA) modes due to its quadratic nature58. With increasing strain, the ZA mode, also called as flexural mode, is stiffened and changes its nature from quadratic to linear. This reduces its contribution towards lattice thermal conductivity but increases its phonon group velocity. The relative displacement of Si and H atoms in different long wavelength vibrational modes near Gamma point is demonstrated in Fig. 4. Out of the twelve modes, the in-phase (out-of-phase) atomic vibrations, called as acoustic (optical) modes, can be visualized from Fig. 4a–c and d–l, respectively. In the realm of acoustic modes, both Si and H atoms play an equally significant role. However, as the frequency of optical modes increases, the involvement of Si atoms diminishes. Nevertheless, H atoms consistently contribute across all vibrational modes. With minimally displaced Si atoms, the H atoms moves in-phase in three optical modes depicted in Figure g, h and l. These modes are associated with the changing dipole moment and are thus identified as infrared (IR) active modes.

As already discussed, the applied strain particularly affects the bonding between Si atoms. The H atoms are displaced horizontally along Si atoms without changing their bonding strength. As a result, only those modes which involve displacement of silicon atoms are affected by applied strain. Figure 4 demonstrate that the three acoustic modes (a, b, c) and two low frequency optical modes (d, e) involve significant vibration of Si along with the H atoms. Only these five modes are affected by the applied strain and shifts downwards in frequency, which can be visualized from their phonon dispersion. The remaining optical modes show minimal contribution from Si atoms, with H atoms predominantly contributing, and these modes maintain their frequency almost unchanged. As a consequence, softening of acoustic and low frequency optical branches is observed which lower their phonon group velocity and encourages anharmonicity. Additionally, the band gap between acoustic and optical branches decreases from 5.35 THz to 0.86 THz as strain increases from 0 to 14%, which quantifies increased acoustic-optical phonon scattering. Therefore, it is logical to assume that increasing strain will result in reduction of lattice thermal conductivity.

The thermal conductivity (κl) expression for a phonon in the i direction, derived from solving the Boltzmann transport equation with relaxation time, is provided as follows:

where summation is over all phonon modes with wave vector q and branch index λ, and \(v\) is phonon group velocity. \(c_{ph}\) and \(\tau \left( {q, {\uplambda }} \right)\) are specific heat of a material and phonon relaxation time, respectively. The values of κl for SiH monolayer is shown in Fig. 5f across temperatures ranging from 100 to 900 K. A decline in κl is observed with increase in temperature as well as strain. The κl of unstrained SiH monolayer at room temperature is 0.99 Wm−1 K−1, which decreases to 0.49 Wm−1 K−1 at 700 K. The fall is owing to the inherent increase in phonon–phonon scattering with temperature. Our calculated κl is in fair agreement with the experimental data59. As the strain is increased, the κl diminishes consistently and reaches a value of 0.27 (0.62) Wm−1 K−1 at stain of + 14% and a temperature of 700 (300) K. This behavior can be discussed using Eq. 1. The primary factors influenced by strain are the phonon group velocity and phonon scattering rates. The group velocity solely depends upon the slope of phonon dispersion, which is directly associated with the bonding strength or elastic properties. Table 2 suggest that the elastic constants decrease monotonically with strain, leading to a softening of phonon modes and a decrease in phonon group velocity, which has a negative impact on κl. The Debye temperature (ΘD) signifies the temperature at which the most prominent normal mode of vibrations of a material occurs. Additionally, it is associated with the elastic properties and is directly linked with the frequency of LA mode. The ΘD of unstrained SiH monolayer is 387 K, which consistently decreases with strain and falls to 282 K at a strain of 14%. Again, the reason being the shifting of acoustic modes towards lower frequency side. Meanwhile, softening of acoustic and low frequency optical modes reduces the band-gap between them. The band-gap reduction directly affects the anharmonicity and enhances Grüneisen parameter, which causes a reduction in κl. These parameters collectively suggest a lowering of κl of SiH monolayer with strain.

Effect of strain on electronic transport

As illustrated above, the external strain is able to tune electronic band structure of SiH monolayer. Ultimately, factors directly tied to the band structure, such as the effective mass (m*), relaxation time (\(\tau\)), and carrier mobility (\(\mu\)) will undergo changes due to strain. These modifications, in turn, influence the thermoelectric characteristics of a material. In this section, the effect of strain on m*, \(\tau\), and \(\mu\), and the resulting impact on the thermoelectric properties of the SiH monolayer is discussed in details.

Table 2 mentions the room temperature values of different parameters at various strains. There is a decreasing order of elastic constant from 41.31 to 4.52 Nm−1 while deformation potential constant does not follow any particular trend with applied strain. An increase in the dispersion of band extremum (VBM and CBM) with strain is clearly visible from electronic band structure. The effective mass of carriers is inversely proportional to band dispersion and hence decreases for both electrons and holes. With the help of all these parameters and using Eq. 4, we have calculated the value of \(\tau\) which shows decreasing behaviour with an increase in strain. This is brought on by combined variation of \(C_{\beta }^{2D }\), \(E_{\beta }^{*}\) and \(m_{ }^{*}\). Additionally, there is more frequent scattering of electrons with lattice phonons at higher temperatures, so the mean free path and hence \(\tau\) shows decreasing trend with an increasing temperature.

The electronic transport coefficients of SiH monolayer are thoroughly estimated using Boltzmann transport equations to assess its thermoelectric performance at different strains. The Seebeck coefficient (S) is not affected by \(\tau\) but depends on m* of carriers. Figure 6 displays the evaluated transport parameters versus chemical potential (\(\mu\)) under different strains and temperatures (T). Positive and negative \(\mu\) depicts electron and hole doping. Pristine SiH monolayer possess ultrahigh S of 2800 (2750) \({\upmu }\) VK−1 for n(p)-type doping at room temperature. The CBM is comparatively flatter than VBM. As a result, the DOS are more asymmetric near CBM as compared to VBM. This makes S to attain higher value for n-type doping than p-type. The maximum value of S is found near \(\mu\) = 0 and T = 300 K, which falls off on both sides as \(\mu\) and T increases. With elevated strain, the value of S decreases and reduces to 207 (200) \({\upmu }\) VK−1 for n(p)-type doping at 14% strain. Along with a decrease in band gap, the dispersion of band extremum also increases with strain which causes a decrease in effective mass of carriers. These two effects in combination are responsible for large fall in the value of S. Interestingly, at 0% and 4% strains, S falls steeply to nearly zero value at low \(\mu\) for T = 300 K, while it falls smoothly for 500 K and 700 K. The steep curve changes into smooth at 8% and 14% strains. This effect is observed in wide band-gap materials where the \(\mu\) resides within the bandgap, resulting in a substantial reduction of available charge carriers and, consequently, a diminished S. When \(\mu\) is within the bandgap (i.e., far from both the conduction and valence bands in large bandgap materials), the exponential term of electron distribution function becomes very large, making the electron distribution function extremely close to either 0 (for conduction band states) or 1 (for valence band states). This creates numerical underflow issues, where the calculated contributions from the electronic states become so small that they fall below the precision limit of code, effectively being treated as zero in the computation [56]. Thus, the computational challenges in calculating the Seebeck coefficient near \(\mu\) = 0 in large bandgap semiconductors arise from a combination of low carrier concentration, numerical precision issues, and the limitations of Boltzmann transport theory. These factors lead to an exaggerated drop in S, even though the physical reason is indeed due to wide bandgap and low carrier density. With increase in strain, the band-gap of SiH monolayer decreases and reaches to 0.21 eV at 14% strain. With fall in magnitude of band gap, the carrier concentration increases and electron distribution function spreads out making it non-zero. This is the reason why steep curve at T = 300 K and strains of 0% and 4% smoothens at higher temperatures and higher strains. Table 3 lists the computed values of S for SiH monolayer at various temperatures and strain percentages. Due to the isotropy of crystal structure, the transport parameters are identical along xx and yy directions.

Figure 7 depicts the variation of \(\sigma\) with \(\mu\) under different strains and temperatures. The peak value of \(\sigma\) for pristine SiH at room temperature for electron (hole) doping is 1.26 (0.74)\(\times\) 107 Sm−1. The magnitude of σ is significantly influenced by τ, which tends to be higher for electron doping compared to hole doping. This is the reason why electrons exhibit greater conductivity than holes. Besides \(\tau\), the quantity whose variation affects \(\sigma\) the most is electronic band gap. As already discussed, there is a large fall in the band gap of SiH monolayer with an increase in strain, which will lead to an enormous increase in \(\sigma\). But at the same time, \(\tau\) also decreases which limits the rise in \(\sigma\). Hence, \(\sigma\) increases steadily and attains a value of 3.09 (1.89) Sm−1 for electron (hole) doping at 14% strain, which is ~ 2 times higher than pristine one. Figure 7a, which is for unstrained case, shows that \(\sigma\) is almost zero in the window range − 1 ≤ \(\mu\) ≤ + 1 and increases quickly beyond this range. This behavior is found in wide band gap materials because they possess very less thermally generated electron hole-pairs. At low doping concentration (low \(\mu\)), there are not enough carriers to conduct and thus \(\sigma\) is almost zero. Thus, pristine SiH shows finite \(\sigma\) only at higher doping concentrations (high \(\mu\)). As strain increases, the band gap starts to decrease which increases the concentration of thermally generated electron–hole pairs. As a result, the nearly zero conductivity window narrows and attains minimum range at 14% strain at which band gap is minimum. This behavior also supports the reduction of band gap with external strain. The computed electronic thermal conductivity (κe) of SiH monolayer is shown in Fig. 8. Since Wiedemann–Franz law (κe = L\(\sigma\)T, where L is the Lorentz number) provides a direct proportionality between κe and \(\sigma\), both these quantities show similar behavior against different strains. The room temperature value of ke for electron (hole) doping is 43.26 (24.88) Wm−1 K−1, which enhances to 63.02 (38.19) Wm−1 K−1 at 14% strain.

Effect of strain on figure of merit

We are now prepared to analyze the thermoelectric figure of merit (ZT) of the monolayer. The variation of ZT with doping and temperature for unstrained as well as strained SiH monolayers are shown in Fig. 9. As discussed in introduction section, the ZT can be enhanced either by increasing thermoelectric power factor or by reducing κl. With increasing strain, the narrowing of band gap adversely affects the Seebeck coefficient, but at the meantime, boosts electrical conductivity. The net effect is an increase in thermoelectric power factor. Furthermore, a nearly sevenfold reduction in κl is observed at a strain of 14%. Consequently, the ZT value, initially measured at 1.66 (1.29) for electron (hole) doping at carrier concentration of 7.32 (7.53) × 1013 cm−2 and temperature of 700 K in the unstrained state, improves under the same temperature conditions at carrier concentration of 2.15 (2.20) × 1013 cm−2 to 2.83 (2.78) for electron (hole) doping at a strain of 14%.

This represents a nearly twofold increase in ZT through the application of strain. In the absence of strain, the maximum ZT value for n-type doping is approximately 1.3 times that of p-type system. Therefore, strain engineering has brought about a much more balanced distribution of ZT values for both n and p-type systems, which is highly advantageous for the design of highly efficient thermoelectric modules.

Conclusion

Based on density functional theory, Boltzmann transport equations and deformation potential theory, electronic and thermoelectric properties of hydrogenated Silicene (SiH monolayer) are systematically investigated under different in-plane biaxial tensile strains. The chemical and dynamical stability enabled us to explore the properties of the monolayer upto a strain of 14% only. Band structure of SiH monolayer is found highly sensitive to biaxial tensile strains. Along with indirect to direct band gap transition with increased strain, the magnitude of band gap generally decreases and monolayer transforms from wide band-gap indirect semiconductor to narrow band-gap direct semiconductor. Meanwhile, the strains effectively influenced electrical transport coefficients such as carrier effective mass, relaxation time, and mobility, ultimately yielding a maximum power factor. At a strain of 14%, there is an observed reduction in lattice thermal conductivity by nearly 43%. The maximum ZT value at 700 K, which was 1.66 for n-type doping in unstrained state, significantly escalates to 2.83 at 14% strain, surpassing values observed in other Silicene-based monolayers. Therefore, it can be inferred that under suitable strain conditions, the SiH monolayer holds promise as a viable candidate for waste heat recovery applications. This work may contribute to ongoing studies of Silicene based monolayers and shed light on research into low-dimensional thermoelectric materials.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Karri, M. A., Thacher, E. F. & Helenbrook, B. T. Exhaust energy conversion by thermoelectric generator: Two case studies. Energy Convers. Manag. 52, 1596–1611 (2011).

Ammar, Y., Joyce, S., Norman, R., Wang, Y. & Roskilly, A. P. Low grade thermal energy sources and uses from the process industry in the UK. Appl. Energy 89, 3–20 (2012).

Dughaish, Z. H. Lead telluride as a thermoelectric material for thermoelectric power generation. Physica B Condens. Matter. 322, 205–223 (2002).

Yang, J. et al. On the tuning of electrical and thermal transport in thermoelectrics: an integrated theory-experiment perspective. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2, 15015–15031 (2016).

Skelton, J. M., Parker, S. C., Togo, A., Tanaka, I. & Walsh, A. Thermal physics of the lead chalcogenides PbS, PbSe, and PbTe from first principles. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. Mater. Phys. 89, 205203–205212 (2014).

Kaur, K., Murali, D. & Nanda, B. R. K. Stretchable and dynamically stable promising two-dimensional thermoelectric materials: ScP and ScAs. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 7, 12604–12615 (2019).

Zhang, X. & Zhao, L. D. Thermoelectric materials: Energy conversion between heat and electricity. J. Materiomics 1, 92–105 (2015).

Wang, D. et al. Enhancing thermoelectric performance of SnTe via stepwisely optimizing electrical and thermal transport properties. J. Alloys Compd. 773, 571–584 (2019).

Naghavi, S. S., He, J., Xia, Y. & Wolverton, C. Pd2Se3 monolayer: A promising two-dimensional thermoelectric material with ultralow lattice thermal conductivity and high power factor. Chem. Mater. 30, 5639–5647 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Simultaneously enhancing the power factor and reducing the thermal conductivity of SnTe via introducing its analogues. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 2420–2431 (2017).

Pei, Y. et al. Multiple converged conduction bands in K2Bi8Se13: A promising thermoelectric material with extremely low thermal conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16364–16371 (2016).

Huang, Z. et al. Improving the thermoelectric performance of p-type PbSe via synergistically enhancing the Seebeck coefficient and reducing electronic thermal conductivity. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 8, 4931–4937 (2020).

Zhao, L. D. et al. High thermoelectric performance via hierarchical compositionally alloyed nanostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 7364–7370 (2013).

Qin, B., Wang, D. & Zhao, L. D. Slowing down the heat in thermoelectrics. InfoMat 3, 755–789 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. The microscopic origin of low thermal conductivity for enhanced thermoelectric performance of Yb doped MgAgSb. Acta Mater. 128, 227–234 (2017).

Ghosh, T., Dutta, M., Sarkar, D. & Biswas, K. Insights into low thermal conductivity in inorganic materials for thermoelectrics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 10099–10118 (2022).

Jana, M. K. et al. Intrinsic rattler-induced low thermal conductivity in Zintl type TlInTe2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4350–4353 (2017).

Cahangirov, S., Topsakal, M., Aktürk, E., Šahin, H. & Ciraci, S. Two- and one-dimensional honeycomb structures of silicon and germanium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 236804 (2009).

Takahashi, T., Sugawara, K., Noguchi, E., Sato, T. & Takahashi, T. Band-gap tuning of monolayer graphene by oxygen adsorption. Carbon N. Y. 73, 141–145 (2014).

Nandee, R., Chowdhury, M. A., Shahid, A., Hossain, N. & Rana, M. Band gap formation of 2D materialin graphene: Future prospect and challenges. Results Eng. 15, 100474 (2022).

Jugdersuren, B. et al. Hydrogenated silicene grown by plasma enhanced chemical-vapor deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 134, 214303–214311 (2023).

Somaiya, R. N., Sonvane, Y. & Gupta, S. K. rscli/pccp. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 3990–3998 (2020).

Khang, N. D., Nguyen, C. Q. & Nguyen, C. V. Theoretical prediction of a type-II BP/SiH heterostructure for high-efficiency electronic devices. Dalton Trans. 52, 2080–2086 (2023).

Hu, Y. F., Yang, J., Yuan, Y. Q. & Wang, J. W. GeI2 monolayer: A model thermoelectric material from 300 to 600 K. Philos. Mag. 100, 782–796 (2019).

Bahuguna, B. P., Saini, L. K., Sharma, R. O. & Tiwari, B. Hybrid functional calculations of electronic and thermoelectric properties of GaS, GaSe, and GaTe monolayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 28575–28582 (2018).

Wani, A. F., Rani, B., Dhiman, S., Sharopov, U. B. & Kaur, K. SiH monolayer: A promising two-dimensional thermoelectric material. Int. J. Energy Res. 46, 10885–10893 (2022).

Fayaz Wani, A., Rani, B., Dhiman, S. & Kaur, K. First principles study of stability and thermoelectric response of GeH monolayer. Mater. Today Proc. (2023).

Zhou, Y. & Zhao, L. D. Promising thermoelectric bulk materials with 2D structures. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702676–1702685 (2017).

Chang, C. et al. Realizing high-ranged out-of-plane ZTs in N-type SnSe crystals through promoting continuous phase transition. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1901334–1901343 (2019).

Huang, L., Chen, Z. & Li, J. Effects of strain on the band gap and effective mass in two-dimensional monolayer GaX (X = S, Se, Te). RSC Adv 5, 5788–5794 (2015).

Farjam, M. & Rafii-Tabar, H. Comment on “band structure engineering of graphene by strain: First-principles calculations”. Phys. Rev. B 80, 167401–167408 (2009).

Pei, Y. et al. Convergence of electronic bands for high performance bulk thermoelectrics. Nature 473, 66–69 (2011).

Fayaz Wani, A., Rani, B., Dhiman, S. & Kaur, K. Band engineering of monolayer CaI2, a first-principles approach. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 9, 1–9 (2023).

Zhang, G. et al. Rational synthesis of ultrathin n-type Bi2Te3 nanowires with enhanced thermoelectric properties. Nano Lett. 12, 56–60 (2012).

Lv, H. Y., Lu, W. J., Shao, D. F. & Sun, Y. P. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of phosphorene by strain-induced band convergence. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. Mater. Phys. 90, 085433–085441 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Enhancing thermoelectric properties of monolayer GeSe via strain-engineering: A first principles study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 521, 146256–146262 (2020).

Gupta, R., Kakkar, S., Dongre, B., Carrete, J. & Bera, C. Enhancement in the thermoelectric performance of SnS monolayer by strain engineering. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 6, 3944–3952 (2023).

Lv, H. Y., Lu, W. J., Shao, D. F., Lu, H. Y. & Sun, Y. P. Strain-induced enhancement in the thermoelectric performance of a ZrS2 monolayer. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 4, 4538–4545 (2016).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: A modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 21, 395502–395511 (2009).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Pack, J. D. & Monkhorst, H. J. Special points for Brillonln-zone integrations—a reply. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 16, 1748–1749 (1977).

Madsen, G. K. H. & Singh, D. J. BoltzTraP. A code for calculating band-structure dependent quantities. Comput. Phys. Commun. 175, 67–71 (2006).

Madsen, G. K. H., Carrete, J. & Verstraete, M. J. BoltzTraP2, a program for interpolating band structures and calculating semi-classical transport coefficients. Comput. Phys. Commun. 231, 140–145 (2018).

Fan, Z., Wang, H. Q. & Zheng, J. C. Searching for the best thermoelectrics through the optimization of transport distribution function. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 073713–073721 (2011).

Jonson, M. & Mahan, G. D. Mott’s formula for the thermopower and the Wiedemann-Franz law. Phys. Rev. B 21, 4223–4229 (1980).

Zhang, J. et al. Titanium trisulfide monolayer as a potential thermoelectric material: A first-principles-based Boltzmann transport study. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 2509–2515 (2017).

Feng, T., Qiu, B. & Ruan, X. Coupling between phonon-phonon and phonon-impurity scattering: A critical revisit of the spectral Matthiessen’s rule. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. Mater. Phys. 92, 235206–235212 (2015).

Bardeen, J. & Shockley, W. Deformation potentials and mobilities in non-polar crystals. Phys. Rev. 80, 72–80 (1950).

Wani, A. F. et al. Intrinsic and strain dependent ultralow thermal conductivity in novel AuX (X = Cu, Ag) monolayers for outstanding thermoelectric applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 21736–21747 (2023).

Xu, L., Yang, M., Wang, S. J. & Feng, Y. P. Electronic and optical properties of the monolayer group-IV monochalcogenides MX (M=Ge, Sn; X= S, Se, Te). Phys. Rev. B 95, 1–9 (2017).

Wang, C. & Gao, G. Titanium nitride halides monolayers: promising 2D anisotropic thermoelectric materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 32, 205503–205512 (2020).

Wang, Y., Li, Y. & Chen, Z. Not your familiar two dimensional transition metal disulfide: Structural and electronic properties of the PdS2 monolayer. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 3, 9603–9608 (2015).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Zhu, X. L. et al. Monolayer SnP3: An excellent p-type thermoelectric material. Nanoscale 11, 19923–19932 (2019).

Araidai, M., Itoh, M., Kurosawa, M., Ohta, A. & Shiraishi, K. Hydrogen desorption from silicane and germanane crystals: Toward creation of free-standing monolayer silicene and germanene. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 125301–125307 (2020).

Mohebpour, M. A., Vishkayi, S. I. & Tagani, M. B. Thermoelectric properties of hydrogenated Sn2Bi monolayer under mechanical strain: A DFT approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 23246–23257 (2020).

Wani, A. F. et al. XO2 (X = Pd, Pt) monolayers: A promising thermoelectric materials. Adv. Theory Simul. 6, 2300158–2300167 (2023).

Shafique, A. & Shin, Y. H. Strain engineering of phonon thermal transport properties in monolayer 2H-MoTe2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 32072–32078 (2017).

Leng, C., Ren, D. & Zhang, L. Improvement of thermoelectric properties for silicene by the hydrogenation effect. Results Phys. 36, 105422 (2022).

Acknowledgements

One of the authors, S.A.K extends his appreciation to the ANRF Science and Engineering Research Board (DST-SERB) India for funding this work through Ramanujan Fellowship Project under grant number RJF/2023/000009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Aadil Fayaz Wani: Investigation, Visualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft preparation Shakeel Ahmad Khandy: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Reviewing and Editing Ajay Singh Verma: Resources, review Shobhna Dhiman: Review, Validation, Analysis Kulwinder Kaur: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wani, A.F., Khandy, S.A., Verma, A.S. et al. Strain induced crystal lattice softening and improved thermoelectric performance of hydrogenated silicene for energy harvesting applications. Sci Rep 14, 29555 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81138-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81138-y