Abstract

A population balance-based model was developed to describe the crystallization kinetics of the SAPO-34 zeotype through the hydrothermal method at three distinct temperatures of 180, 200, and 220 °C. The synthesized SAPO-34 catalysts were characterized by XRD, FESEM, BET, and DLS analysis. The model was constructed based on XRD patterns and incorporated established kinetic expressions for homogeneous nucleation and diffusion-controlled crystal growth. The developed model was also employed in a well-mixed batch system to predict the crystal size distribution. To solve the model equations, the Grey Wolf Optimization technique, as a powerful tool for optimizing complex systems, was applied. Then, the experimental data and the model’s predictions from zeolite synthesis were compared. Specifically, the nucleation rate, growth rate, crystallization profiles, and mean size of the resulting product crystals of SAPO-34 were evaluated for the first time. Remarkably, a notable agreement between the model and the experimental outcomes, particularly concerning the mean crystal size, was demonstrated. This connection between theory and experiment underlined the effectiveness of the population balance-based model in describing the complex crystallization process of the SAPO-34 zeotype across the range of temperatures. Indeed, this investigation demonstrated valuable insights into the hydrothermal synthesis of SAPO-34, showing the value of population balance modeling in predicting and optimizing crystallization processes. In addition, such findings indicated a great deal of promise for enhancing the precision and control of zeolite crystallization, a key element in several industrial applications, such as catalysis, ion exchange, and adsorption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The silico-aluminophosphate molecular sieve, SAPO-34, with a Chabazite (CHA) structure, has demonstrated remarkable performance as a membrane or adsorbent in the sorption process and as a catalyst in methanol-to-olefin (MTO) reactions1,2. The MTO reaction has been investigated under various reaction conditions and on several zeolitic structures, including ZSM-5, SAPO-34, mordenite, etc.3,4. The SAPO-34 catalyst exhibits exceptional selectivity for lower olefins and complete conversion of methanol in the MTO reaction because of its tiny pores, medium acidity, and good thermal and hydrothermal stability. However, coke can quickly deactivate while blocking the SAPO-34 crystals’ internal channels entirely5,6. Using the SAPO-34 catalyst with a small crystallite size enhances the accessibility of methanol into its cages, resulting in a better catalytic performance. Thus, optimizing the zeotype SAPO-34 particle size distribution (PSD) is essential to prolong the catalyst’s lifetime and activity7,8. PSD is controlled simultaneously by several factors; namely, primary nucleation, crystal growth, and aggregation effectively determine the resultant PSD. From a production point of view, optimized control of the PSD, particularly improving process reproducibility, remains a critical concern9,10. Since theoretical identification of PSD avoids many experiments and generates significant expenses, mathematical modeling or numerical simulation can be used to accomplish the above and better understand the process11.

Zeolite modeling employs three primary methodologies: empirical, reaction engineering, and population balance models (PBM)12. Empirical models highlight fitting mathematical relationships to experimental data, often lacking a robust theoretical foundation13. However, the reaction engineering model employs multiple classical bimolecular-type reactions during the zeolite crystallization14. In addition, the population balance methodology is widely applied to analyze particulate systems like crystallization, fermentation, aerosols, precipitation, etc. The concept of PBM is based on the conservation of particles growing along a size axis in a given environment. Predictions of the crystal size distribution and its characteristics are possible by the population balance, whereas with the other two models, this cannot be resulted. Besides, PBM can encompass nucleation, growth, aggregation, and breakage15,16.

Thompson and Huber17 applied PBM to synthesize zeolite A for the first time. It was indicated that zeolite A’s growth rate decreases as particle size increases. In addition, it was demonstrated that the product crystal morphology may be controlled by adjusting the silica-to-alumina ratio in the batch composition. For hydrothermal zeolite synthesis, Thompson and Dyer18 proposed a PBM that could analytically predict the statistical moments of the zeolite crystal size distribution by including a fluid phase homogeneous nucleation rate and constant linear crystal growth. The “characteristic method” was used to numerically generate the number density function of the PSD. To determine if the kelvin effect could account for the zeolite crystallization induction period, it was included in the growth-rate expression of PBM by Warzywoda et al.19. The Kelvin effect explains particle-size-dependent crystal dissolution and the improved vapor pressure of relatively small liquid droplets. It is a surface behavior associated with the curvature of the tiny particles. The findings indicate that early events in the liquid solution are crucial to interpreting zeolite crystallization, as the kelvin effect cannot explain the apparent lag time. Chen et al.20 successfully utilized modified population balance equations to establish a connection between zeolite A’s transient crystallization and crystal size distribution. It was found that the growth surface reaction could function as the controlling step for zeolite A, which was synthesized hydrothermally and without any hydrodynamic effect. A consistently high degree of agreement was found between the predictions and the experiments, particularly between the mean crystal size and the expected variance of the crystal size distribution. The effect of gravity on the crystallization kinetics and particulate properties in a zeolite crystal growth process was discussed by developing a mathematical model based on the heterogeneous and secondary nucleation and size-dependent power-law growth mechanisms21. Falamaki et al.22 used a population balance approach and modified autocatalytic nucleation to model the synthesis of ZSM-5 zeolite with 1,6-hexanediol as a structure-directing agent in a vigorously agitated system. The study investigated the kinetics of nucleation and crystallization processes. It was indicated that releasing initial nuclei with nonuniform distribution during the crystallization process could accurately describe the nucleation rate with a temperature dependency of these nuclei’s activity. In another work, the population balance technique examined the sub-micrometer zeolite ZSM-5 crystallization in a tetrapropyl ammonium-free reaction. Two distinct sizes of silicalite-1 seed crystals (260 and 690 nm) were added to start the experiment. The outcomes demonstrated that the population balance approach was effectively used to control and predict the particle features of crystalline end products23. Bhoi et al.24 described the development of a PBM for unseeded batch cooling crystallization of L-asparagine monohydrate (LAM) from its aqueous solution using ultrasonic assistance. The model takes into account nucleation, growth, and breakage and was solved by high-resolution finite volume discretization with a flux limiter. It was shown that ultrasound could enhance the nucleation rate, resulting in early nucleation and substantially reducing the metastable zone width for (LAM), according to experimental data and model simulations. Masoodiyeh et al.9 reported the PSD prediction model of zirconia in a supercritical water synthesis process. The model utilized the population balance equation and the method of moments to solve for particle number density and PSD, considering nucleation, growth, and aggregation. The results showed good convergence with experimental PSDs, confirming the importance of considering aggregation in PSD modeling. Rosenbaum et al.25 investigated the application of a PBM for predicting the PSD in a crystallization process of an active pharmaceutical ingredient. The study utilized lab-scale experiments to develop the PBM and then applied the model to predict the product PSD for plant-scale batches, showing good agreement with the measured data. In our research team, the SAPO-34 crystallization has mostly relied on the respective kinetic study26. Namely, we tried to delve into the reaction pathway through kinetic activation barrier consideration. However, the lack of a comprehensive correlation between the crystallization process and PSD should yet be addressed.

In addition, despite such literature revolving around employing PBM to predict the PSD of the synthesized advanced materials, a broad range of such significant materials should still be studied. To date, no investigation has been carried out to study the SAPO-34 crystallization using the population balance model. This particular study aims to apply the PBM to describe the corresponding crystallization and predict the distribution of particle sizes. Zeotype SAPO-34 was developed hydrothermally at three different temperatures to address this objective.

Experimental method

Synthesis of SAPO-34

1.0 Al2O3: 1.0 P2O5: 0.6 SiO2: 4.0 morpholine: 70 H2O was the molar content of the gel used to synthesize SAPO-34 crystals. The framework’s constituent elements Al, P, and Si were obtained from phosphoric acid (Merck), aluminum isopropoxide (Al(OPri)3, Merck), and tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, Merck). Morpholine (fluka) was utilized as a structure-directing agent in this investigation.

Morpholine, distilled water, and aluminum isopropoxide were carefully mixed, and the mixture was continuously stirred until the aluminum precursor was dissolved entirely to prepare the SAPO-34 precursor gel. The next step was adding TEOS to the mixture, followed by adding phosphoric acid. More stirring was applied to the synthesized gel to create a homogenous reaction mixture. The resulting gel was then placed in a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and subjected to heating in an oven at different times and temperatures (180, 200, and 220 °C) while under autogenous pressure. Centrifugation was used to separate the solid product, which was then rinsed in distilled water and dried at 110 °C. The synthesized samples were calcined at 550 °C for 5.5 h to eliminate the template molecules. Table 1 displays the crystallization conditions and features of various SAPO-34 samples synthesized via the hydrothermal method.

Characterization of the synthesized SAPO-34

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the synthesized powder obtained by an Equinox 3000 diffractometer operating at 40 kV and 30 mA with a Cu Ka X-ray source (k = 1.54056 Å) at room temperature were used to determine the phase and crystallinity of the samples. The samples’ relative crystallinity is ascertained by adding the peak intensities at 2θ = 9.6, 12.96, 20.7, and 30.927 and contrasting the results with the reference sample. The reference sample is typically highly crystalline and free of impurities.

The crystallite sizes of samples were determined according to Scherrer’s equation (Eq. 2). In this equation, D is the crystallite size (nm), λ is the X-ray wavelength equivalent to 0.154 nm, β is the line width at half the maximum intensity (FWHM), and θ is Bragg angle28. Indeed, the XRD diffraction patterns are used to identify the crystallite size of catalysts, and the Origin software can evaluate this parameter.

The particles’ morphology was examined using a TESCAN MIRA3 field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM). The quantitative study of FESEM images was done using Image J software. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to determine the hydrodynamic diameter and size distribution of the SAPO-34 zeotype nanoparticles using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire) (wavelength: 657 nm, scattering angle: 135°). After ultrasonically dispersing powder for 1 h at 20 °C in ethanol, the size distribution of zeolite crystals was investigated by DLS. With the nitrogen adsorption method (Micromeritics Tristar II 3020 ), the specific surface area of the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) was observed. Using the t-plot approach, the micropore volume and exterior surface area were determined.

Model development

Population balance equation

Population balance equations describe the features of particles in space and time. Besides particle transportation, nucleation, growth, aggregation/agglomeration, and breaking are also taken into consideration by the population balance equation16. For an isothermal batch crystallizer with a constant volume, the number density function, n(L, t), must be defined as the first step in the population balance method, which characterizes the changing zeolite crystal-size distribution21,29. The following equations must be solved to find this function:

In which the initial and boundary conditions are provided by:

Where L represents the linear crystal’s length, Q and t stand for its growth rate and time, respectively. Suitable initial and boundary conditions must be specified to effectively characterize the system.

Equation 3 through 5 are based on a few assumptions, including (i) the reactor’s components are mixed uniformly, and the system has an isothermal adjustment; (ii) the output stream and the reactor have the same composition; (iii) The system’s total volume stays constant; (iv) there are no crystals in the feed stream; (v) nucleation only produces nuclear-sized particles; and (vi) the size of the crystals has no effect on the rate of crystal formation.

Moment method

The respective partial differential equation can be written as a number of dynamic moment equations. This results in a sequence of ordinary differential equations that are easier to solve and often just as useful as the original equation. The moments of the distribution are defined as follows9,30:

The ith crystal size distribution moment is denoted by \(\:{m}_{i}\). When Eq. 6 is substituted into Eqs. 3–5, a system of moment equations is as follows:

The nucleation rate is represented by B. In addition, \(\:{\text{m}}_{0}\) represents the number of nuclei in the solution, and Q and B are considered independent of crystal size. In order to effectively use the mentioned equation, nucleation and growth rates must be specified in terms of time-dependent state variables. The species concentration is typically of great importance in the various present phases. This finding suggests that the solution algorithm must include mass balance equations for each step.

Nucleation rate

Zeolite crystallization proceeds according to the standard homogeneous nucleation rate expression in the absence of hydrodynamic or shearing effects on nucleation31:

Where A is the interfacial energy factor, S is the relative supersaturation, which is expressed as \(\:{\text{G}}^{\text{*}}/{\text{G}}_{\text{s}}^{\text{*}}\) (divide the solute concentration by the equilibrium concentration.). β stands for the frequency factor. At the pH and temperature of synthesis, the saturation concentration of solute entities in equilibrium with zeotype crystals is represented by the value \(\:{\text{G}}_{\text{s}}^{\text{*}}.\) The hydrodynamic or shearing effects were excluded from nucleation, resulting in a simplified interfacial tension term σ to A as follows:

Where \(\:{\text{N}}_{\text{A}}\) represents the Avogadro constant, T, R, and \(\:{\text{V}}_{\text{m}}\) stand for temperature, gas constant, and unit cell’s volume, respectively.

Crystal growth

Transferring nutrient species from the solution to the crystal surface and integrating them into the crystal is the crystal growth process. We suggest the growth mechanism can be triggered by Brownian motion, which causes the SAPO-34 precursors of the pseudo-cells to approach the nuclei’s surface after dissolving in the solution phase from the gel. Such pseudo-cells integrate once they reach the crystal surface, which speeds up the crystal development process20,29. The following basic steps have been proposed to be involved in the crystal surface reaction:

The pseudo-cell is denoted by P, the pseudo-cell precursor by M, N, N*.and Nn indicate zeotype nuclei, intermediate species, and crystal containing n-1 pseudo-cells, respectively. The \(\:{\text{k}}_{1}^{{\prime\:}}\),\(\:{\text{k}}_{2}^{{\prime\:}}\) \(\:{\text{k}}_{3}^{{\prime\:}}\) and\(\:{\:\text{k}}_{4}^{{\prime\:}}\).parameters indicate the rate constants for gel dissolution, reverse gel dissolution, intermediate species breeding, and crystal growth, respectively.

The total equation that is obtained by repeating and adding the precipitation reactions over n unit cells is as follows:

According to the above procedure, the final crystal would have a nucleus and n pseudo-cells. We apply a power law size-independence on supersaturation of the linear crystal growth rate as follows:

Where the mass transfer coefficient denotes k4 and m constitutes the order of growth. \(\:\text{m}\:=\:1\) implies diffusion-controlled growth rates, whereas surface reaction-controlled growth rates are shown by \(\:\text{m}\:=\:0.5\). In the latter method, half a pseudo-cell is precipitated on the crystal surface by surface reaction stepwise until the supersaturation level reaches equilibrium.

Mass balance of pseudo-cell in gel and solution

The solute concentration affects the nucleation and growth rates of this transient process. The particular solute is usually liberated from the amorphous gel phase, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Thus, material balances on both the solute and amorphous gel phases are needed. In general, these balances can be stated as follows32:

The forward and backward dissolution rates are represented by the first and second terms on the right side of Eqs. 17 and 18, respectively. The fourth and third components in Eq. 18 describe the pseudo-cell consumption rates during nucleation and growth.

The nucleus, which consists of eight pseudo-cells, is indicated by the coefficient of the third term. Ideally, \(\:{\text{k}}_{1}\) and \(\:{\text{k}}_{2}\) dissolution rate constants should be measured separately. However, isolated measurements are incredibly challenging due to the precipitation system’s complexity; as a result, parameter values should be estimated. N, the number of unit cells participating in the homogeneous nucleation process, is typically represented as a very small integer ranging from 1 to 8. It should be noted that with a unit cell diameter of 12.32 A°, zeotype SAPO-34 has a pseudo-cell density of \(\:1.216\times\:{10}^{21}\) cm3. The geometric form factor φ, for a cubic SAPO-34 crystal, equals 633.

Kinetic parameter estimation

The population balance model’s numbers and the fraction of zeotype SAPO-34, or crystallinity in the solid phase, are connected by:

For the kinetic model to be able to produce somewhat accurate and practical predictions, realistic values for the kinetic parameters, such as \(\:{\text{m}}_{0},{\text{m}}_{1},{\text{m}}_{2},\:\text{B},\:\text{Q},\:\text{G},{\text{G}}^{\text{*}}\), must be estimated. The following objective function (see Eq. 20) was used to minimize the difference between the concentration data obtained from the experimental measurements and the concentration predicted by the developer model. Such a function can estimate the kinetic parameters through a nonlinear optimization process, i.e., the Grey Wolf Optimization technique. Flowcharts for the algorithms are depicted in Fig. 2 34.

Results and discussion

FESEM analysis

The FESEM images of the samples are presented in Fig. 3. The typical cubic structure of SAPO-34 is evidently observed, which is quite similar to natural chabazite35. Based on the quantitative result of the FESEM image, the average particle size of the S-180-8, S-200-5, and S-220-3 samples synthesized at 8, 5, and 3 h crystallization times is 5.4, 4.8, and 3.2 μm, respectively. A potential explanation for the small particles of S-220-3 could be that the solute becomes more soluble at higher temperatures, which prevents the growth from continuing and ultimately stops36.

XRD analysis

Figure 4 shows the representative XRD patterns of the developed catalysts at 220° C in the 2θ range of 5 to 40°. The XRD patterns of S-180 and S-200 are presented in Fig. S1 and S2 (supplementary data). The well-resolved peaks of a SAPO-34 zeolite framework without crystalline impurities can be observed3,37. The significant peaks of the synthesized sample emerge at 2θ = 9.4–9.6, 13.0–13.1, 20.8–21.0, and 31.0–31.2 °. As illustrated in Fig. 4, increasing the crystallization time causes further crystal growth; hence, a corresponding rise in the peaks’ intensity is detected. Therefore, to obtain fully crystalline SAPO-34 crystals, at least 3 h of the synthesis time is needed. The crystallite size of the sample determined according to Scherrer’s equation equals 39 nm.

BET-BJH analysis

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm of the samples in Fig. 5 illustrates type I and IV isotherms38,39. A significant increase is noted at the very beginning of the isotherm, suggesting the presence of micropores in the samples. There is another distinct abrupt inflection at P/P0 = 0.3–1.0. According to the IUPAC classification, each sample exhibits the hysteresis loop type H4, which is typical for narrow slit-like pores formed from clusters of platelike particles, as shown in Fig. 5. The BJH analysis of the samples shows a narrow peak around 4 nm, this further supports the presence of mesopores40,41.

The results of adsorption measurements, including the BET surface, are collected in Table 2. Comparing S-180-8 and S-220-3 samples shows that with an increase in the synthesis temperature from 180 to 220 °C, the surface area increases from 357.69 to 401.25 \(\:{\text{m}}^{2}{\text{g}}^{-1}\), respectively, demonstrating that the size of the particles is getting smaller.

To this point, matters have covered obtaining the necessary experimental data and the hydrothermal synthesis of SAPO-34. The synthesis of SAPO-34 is featured by the amorphous gel and the supersaturated solution while the silicon, aluminum, and phosphorus sources are mixed. These phases coexist in an equilibrium state in which nuclei gradually emerge from the solution phase, indicating the start of the crystal growth phase. The population balance equation is used in the following sections to predict the nucleation, growth rate, and particle size distribution.

Population balance model

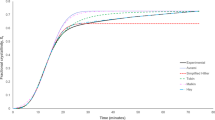

At three distinct temperatures, the results of the synthesis kinetics with model prediction are displayed in Figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9. The model can effectively describe the entire process, from nucleation to crystallization completion. Table 3 indicates the parameters \(\:\text{A},{\upbeta\:},{\text{k}}_{1},{\text{k}}_{2},{\text{k}}_{4}\:\)that were estimated from curve-fitting using the least square method and used in the model estimation.

As predicted by Eq. 11, the interfacial energy (A) has decreased with increasing temperature. The pre-exponential factor β in homogenous nucleation is of the order of 1027–30, which depends on the molecules’ diameter and diffusion rate in a solution. The parameters

and \(\:{\text{k}}_{2}\:\)are relatively constant as a function of temperature. Measurement of these parameters is difficult in practice concerning the complexities of the reaction system. The values in the table make it evident that the kinetic parameter \(\:{\text{k}}_{4}\), which is associated with the particle growth rate, is related to temperature. Its value increases as the temperature rises. The results on transient crystallinity and their model predictions according to Eq. 20 are shown in Fig. 6 (a), indicating a good agreement between the experimental and model outcomes. The crystallization curves have a sigmoid shape, indicating two distinct stages: induction to form nuclei and rapid crystal growth. The crystallization rate is nearly constant after the induction stage and begins to decline at the end43. These curves are similar to those reported in the literature [26, 44]. The amount of crystallization time required to reach a crystallinity of approximately 4% is known as the induction time (\(\:{\text{t}}_{\text{o}}\)) 44. The induction time for samples synthesized at 180, 200, and 220 °C is 90, 60, and 18 min, respectively, demonstrating a notable decrease in the induction time when the crystallization temperature increases. Slopes of crystallization curves suddenly alter after the induction period due to the rapid growth of crystallites. Moreover, the crystallization graph can be used to determine the stable time (\(\:{\text{t}}_{\text{s}}\)), or the duration of crystallization after the approximate retention of crystallinity. Figure 6(a) reveals that reducing the crystallization temperatures by 40 °C extends the stable times by approximately 1.5 h.

Figure 6(b) illustrates a quantitative version of the time alteration of the model’s two main phases: pseudocell concentration in the gel phase and zeolite percentage in the solid phase. These curves are developed from our interactions with the model, which may be understood by analyzing a sequential reaction process. There are two solid phases present: amorphous gel and zeolite crystal phase, both attempting to achieve equilibrium with a shared solution phase intermediate. Without crystallization, the amorphous gel dissolves until the solution phase approaches its limiting value. However, the solution phase concentration rarely surpasses that level due to fast nucleation and crystal formation, which reduces\(\:\:{\text{G}}^{\text{*}}\). At very long times, the system reaches the equilibrium state in which \(\:\text{G}\left(\text{t}\right)\to\:0\)

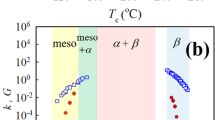

Figure 7 shows a plot of nucleation versus time for three different temperatures. It is observed that how the nucleation centers decrease with increasing temperature. In fact, a decrease in nucleation density at higher temperatures can be explained by accounting for factors like supersaturation, the nuclei’s critical radius, and the energy formation of critical nuclei16. Thus, if the temperature is increased from 180 to 220 °C, the maximum value of the nucleation rate declines from 6.2 × 106 to 4.35 × 106. Homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation are the two fundamental nucleation mechanisms that are generally distinguished. However, homogeneous nucleation theory can be attributed to the current experimental results since no impurities have been purposefully added. According to the homogeneous nucleation theory, several molecules are incorporated by random collision to form a stable nucleus that grows. If this stable nucleus would not reach a certain critical radius (\(\:{\text{r}}_{\text{c}}\)), it might probably dissolve based on the corresponding thermodynamic consideration. As long as there is enough solute available, the energy relations promote further growth beyond \(\:{\text{r}}_{\text{c}}\). For supersaturation S, the Gibbs-Thomson relation is as follows36,45:

Where k and \(\:{\text{V}}_{\text{m}}\) are Boltzmann’s constant and unit cell’s volume, respectively. Equation 21 makes it clear that supersaturation decreases with temperature, which can reduce the nucleation density. Additionally, as the reaction temperature rises, the solubility of the amorphous gel in the liquid phase increases. Therefore, it might be supposed that there would be more probability for nuclei smaller than a certain size to dissolve in the liquid phase by increasing the temperature, resulting in an apparent decrease in the value of B (see Eq. 10)36.

The growth rate over time is observed in Fig. 8 (a), which actually indicates that with an increase in temperature, the rate of crystal growth increases. It can be observed that the growth rate of crystals in solutions with different temperatures starts to increase and then experiences a downward trend after reaching its maximum value. Furthermore, the sample grows to its maximum level faster at higher temperatures. Figure 8 (b) confirms the linear relationship between crystal growth rate and \(\:{\text{G}}^{\text{*}}\) while also demonstrating that the slope of the graph increases with temperature. For SAPO-34, mass transfer mechanisms significantly control the crystal’s growth during hydrothermal synthesis.

Two primary processes, diffusion- and convection-controlled growth, can occur within the mass transfer limiting method. According to concentration gradient and molecular diffusion rates, solute species migrate from the bulk solution into the crystal surfaces in diffusion-controlled growth. The crystal growth rate is restricted by solute molecules’ ability to move toward the crystal surface at a specific rate. The solute molecules accelerate as the temperature rises. Due to the rapid diffusion rate, more solute diffused to the growth surface in a shorter time. The growth units’ diffusion and attachment to the surface growth sites occurred quickly. As a result, the step motion speed and the normal growth rate increase with an increase in temperature. The crystal growth phase persists until the supersaturation state reaches equilibrium, at which the rate of crystal growth and the rate of dissolution align. The SAPO-34 crystals reach the intended size and morphology, signifying that the crystal growth process is completed46,47.

Figure 9 shows The crystal size distributions from the experiment and the model. Not only the average crystal size but also the variation of distribution are all in reasonably good agreement with the experimental data from DLS. As an illustration of the model’s flexibility, consider sample S-220, where the model overlapped at times of 170 and 180 min20. The functions of homogeneous nucleation and growth, in which diffusion is the controlling step and the value of m is equal to 1, are appropriately chosen, which shows that the particle size distribution obtained from the model agrees well with the experimental results. Particle size distribution graphs indicate that the sample synthesized at a higher temperature has an average particle size of 3.18 microns, which is smaller than the sample synthesized at 200 °C, with an average particle size of 4.78 microns.

When it comes to crystal size distribution, both temperature and time can impact the growth or dissolution of crystals. Generally, increasing temperature and shortening the time can change crystal size distribution differently. Namely, increasing the temperature generally promotes crystal growth. Higher temperatures provide more energy to the system, enhancing the diffusion rate and allowing for faster crystal growth46. As a result, larger crystals tend to form at higher temperatures. Shortening the time available for crystal growth or dissolution can limit the extent of crystal size development. If the time is insufficient for significant growth or dissolution, the crystal size distribution may be dominated by smaller crystals.

Conclusion

Since optimizing the PSD of the SAPO-34 crystals was essential to prolonging the catalyst’s lifetime and activity, the population balance model based on hypothetical unit-cell molecules was used to study SAPO-34 crystallization at different times and temperatures. This model considered homogenous nucleation and diffusion-controlled crystal growth mechanisms, independent of the size of the crystals, for the hydrothermal synthesis of SAPO-34. It was found that with increasing temperature, there would be more probability for nuclei smaller than a certain size to dissolve in the liquid phase, resulting in an apparent decrease in the nucleation centers. An increase in temperature led to accelerated crystal growth through the intensified diffusion of molecules towards the crystal surface. In addition, the average crystal size and the distribution variation are all in reasonably good agreement with the experimental data, so the model can be effectively employed to predict the particle size distribution of SAPO-34 across a wide range of synthesis conditions with varying parameters.

Data availability

Data will be available upon the request to the corresponding author.

References

1. Askari, S., et al., Different techniques and their effective parameters in nano SAPO-34 synthesis: A review. Powder Technology, 2016. 301: p. 268–287.

2. Han, J., et al., Revealing inherent factors of SAPO-34 zeolites etching towards the fabrication of hierarchical structure. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2021. 319: p. 111067.

3. Askari, S., Z. Sedighi, and R. Halladj, Rapid synthesis of SAPO-34 nanocatalyst by dry gel conversion method templated with morphline: investigating the effects of experimental parameters. Microporous and mesoporous materials, 2014. 197: p. 229–236.

4. Chen, D., et al., The effect of crystal size of SAPO-34 on the selectivity and deactivation of the MTO reaction. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 1999. 29(1–2): p. 191–203.

5. Askari, S. and R. Halladj, Effects of ultrasound-related variables on sonochemically synthesized SAPO-34 nanoparticles. Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 2013. 201: p. 85–92.

6. Askari, S., R. Halladj, and M. Sohrabi, Methanol conversion to light olefins over sonochemically prepared SAPO-34 nanocatalyst. Microporous and mesoporous materials, 2012. 163: p. 334–342.

7. Zhang, Y., et al., synthesis of small-sized SAPO-34 crystals with varying template combinations for the conversion of methanol to olefins. Catalysts, 2018. 8(12): p. 570.

8. Lee, K.Y., et al., effect of crystallite size of SAPO-34 catalysts on their induction period and deactivation in methanol-to-olefin reactions. Applied Catalysis A: General, 2009. 369(1–2): p. 60–66.

9. Masoodiyeh, F., M. Mozdianfard, and J. Karimi-Sabet, Modeling zirconia nanoparticles prepared by supercritical water hydrothermal synthesis using population balance equation. Powder Technology, 2017. 317: p. 264–274.

10. Zhao, J., et al., Numerical study on particle size distribution in the process of preparing ultrafine particles by reactive precipitation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2005. 110(1–3): p. 19–29.

11. Rawlings, J.B., S.M. Miller, and W.R. Witkowski, Model identification and control of solution crystallization processes: a review. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 1993. 32(7): p. 1275–1296.

12. Thompson, R.W. and A. Dyer, Mathematical analyses of zeolite crystallization. Zeolites, 1985. 5(4): p. 202–210.

13. Kerr, G.T., Chemistry of crystalline aluminosilicates. IV. Factors affecting the formation of zeolites X and B. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 1968. 72(4): p. 1385–1386.

14. THOMPSON, R.W., A Reaction Engineering Model for Zeolite A Synthesis. Chemical Engineering Communications, 1980. 4(1–3): p. 127–133.

15. Randolph, A.D. and M.A. Larson, Transient and steady state size distributions in continuous mixed suspension crystallizers. AIChE Journal, 1962. 8(5): p. 639–645.

16. Randolph, A., Theory of particulate processes: analysis and techniques of continuous crystallization. 2012: Elsevier.

17. Thompson, R.W. and M.J. Huber, Analysis of the growth of molecular sieve zeolite NaA in a batch precipitation system. Journal of Crystal Growth, 1982. 56(3): p. 711–722.

18. Thompson, R.W. and A. Dyer, A modified population balance model for hydrothermal molecular sieve zeolite synthesis. Zeolites, 1985. 5(5): p. 292–301.

19. Warzywoda, J., R.D. Edelman, and R.W. Thompson, Thoughts on the induction time in zeolite crystallization. Zeolites, 1989. 9(3): p. 187–192.

20. Chen, W.H., H.C. Hu, and T.Y. Lee, Transient crystallization and crystal size distribution of zeolite A. Chemical engineering science, 1993. 48(21): p. 3683–3691.

21. Song, H., O.J. Ilegbusi, and A. Sacco Jr, Effects of gravity on zeolite crystallization from solution. Journal of crystal growth, 2005. 277(1–4): p. 623–630.

22. Falamaki, C., M. Edrissi, and M. Sohrabi, Studies on the crystallization kinetics of zeolite ZSM-5 with 1, 6-hexanediol as a structure-directing agent. Zeolites, 1997. 19(1): p. 2–5.

23. Ren, N., et al., Seed-induced, structure directing agent-free crystallization of sub-micrometer zeolite ZSM-5: A population balance analysis. Crystal growth & design, 2012. 12(4): p. 1736–1745.

24. Bhoi, S. and D. Sarkar, Modelling and experimental validation of ultrasound assisted unseeded batch cooling crystallization of L-asparagine monohydrate. CrystEngComm, 2016. 18(25): p. 4863–4874.

25. Rosenbaum, T., et al., Population balance modeling to predict particle size distribution upon scale-up of a combined antisolvent and cooling crystallization of an active pharmaceutical ingredient. Organic Process Research & Development, 2019. 23(12): p. 2666–2677.

26. Shalmani, F.M., R. Halladj, and S. Askari, An investigation of the crystallization kinetics of zeotype SAPO-34 crystals synthesized by hydrothermal and sonochemical methods. Ultrasonics sonochemistry, 2016. 29: p. 354–362.

27. Szostak, R., Molecular sieves. Vol. 234. 1998: Springer.

28. Burton, A.W., et al., On the estimation of average crystallite size of zeolites from the Scherrer equation: A critical evaluation of its application to zeolites with one-dimensional pore systems. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2009. 117(1–2): p. 75–90.

29. Song, H., O.J. Ilegbusi, and A. Sacco Jr, Kinetics of zeolite NaA crystallization in microgravity. Materials Letters, 2005. 59(21): p. 2668–2672.

30. Nikolakis, V., D.G. Vlacho, and M. Tsapatsis, Modeling of zeolite crystallization: the role of gel microstructure. Microporous and mesoporous materials, 1998. 21(4–6): p. 337–346.

31. Sheikh, A.Y., A.G. Jones, and P. Graham, Population balance modeling of particle formation during the chemical synthesis of zeolite crystals: Assessment of hydrothermal precipitation kinetics. Zeolites, 1996. 16(2–3): p. 164–172.

32. Warzywoda, J. and R.W. Thompson, Analysis of zeolite crystallization with autocatalytic nucleation. Zeolites, 1989. 9(4): p. 341–345.

33. Breck, D.W., Zeolite molecular sieves: structure, chemistry, and use. (No Title), 1974.

34. Bosetti, L. and M. Mazzotti, Population balance modeling of growth and secondary nucleation by attrition and ripening. Crystal Growth & Design, 2019. 20(1): p. 307–319.

35. Nishiyama, N., et al., Size control of SAPO-34 crystals and their catalyst lifetime in the methanol-to-olefin reaction. Applied Catalysis A: General, 2009. 362(1–2): p. 193–199.

36. Shedam, M. and A.V. Rao, Effect of temperature on nucleation and growth of cadmium oxalate single crystals in silica gels. Materials chemistry and physics, 1998. 52(3): p. 263–266.

37. Najafi, N., S. Askari, and R. Halladj, Hydrothermal synthesis of nanosized SAPO-34 molecular sieves by different combinations of multi templates. Powder technology, 2014. 254: p. 324–330.

38. Bardestani, R., G.S. Patience, and S. Kaliaguine, Experimental methods in chemical engineering: specific surface area and pore size distribution measurements—BET, BJH, and DFT. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 2019. 97(11): p. 2781–2791.

39. Wang, X., et al., Excellent catalytic performance for methanol to olefins over SAPO-34 synthesized by controlling hydrothermal temperature. Catalysis Communications, 2018. 108: p. 64–67.

40. Labani, M.M., et al., Evaluation of pore size spectrum of gas shale reservoirs using low pressure nitrogen adsorption, gas expansion and mercury porosimetry: A case study from the Perth and Canning Basins, Western Australia. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 2013. 112: p. 7–16.

41. Yang, H., et al., synthesis and catalytic performances of hierarchical SAPO-34 monolith. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 2010. 20(16): p. 3227–3231.

42. Zeng, S.-z., et al., The formation mechanisms of porous silicon prepared from dense silicon monoxide. RSC advances, 2017. 7(13): p. 7990–7995.

43. Joshi, P., et al., Influence of template on crystallization of ZSM-5 zeolites. Journal of inclusion phenomena and molecular recognition in chemistry, 1990. 9: p. 91–99.

44. Turta, N., et al., effect of crystallization temperature on the synthesis of ETS-4 and ETS-10 titanosilicates. Journal of Porous Materials, 2009. 16: p. 527–536.

45. Springer, G.S., Homogeneous nucleation. Advances in Heat Transfer, 1979. 14: p. 281–346.

46. Li, W., et al., Influence of temperature on the growth and surface morphology of Fe 3 + poisoned KDP crystals. RSC advances, 2017. 7(28): p. 17531–17538.

47. Eisenschmidt, H., A. Voigt, and K. Sundmacher, Face-specific growth and dissolution kinetics of potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystals from batch crystallization experiments. Crystal Growth & Design, 2015. 15(1): p. 219–227.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. wrote the original draft. S.H. and R.H. supervised the project. F.M. edited the main text and interpreted the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verki, M.T., Halladj, R., Habibzadeh, S. et al. Crystallization and particle size distribution of hydrothermally synthesized SAPO-34: an experimental and population balance study. Sci Rep 15, 6301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81146-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81146-y