Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the ability of serial whole-body dynamic PET/CT to differentiate physiological from abnormal 18F-FDG uptake in the abdomen and pelvis of gynecological cancer patients. We conducted a retrospective study of 61 18F-FDG PET/CT examinations for suspected gynecological malignancies or metastases between March 2018 and January 2020. Our protocol included four-phase dynamic whole-body scans. High-uptake foci with SUVmax > 2.5 in the abdominopelvic region caudal to the renal portal were picked up and visually evaluated as “changed” (disappeared during any phase or morphological changes in more than half of the foci) or “unchanged” in motion on the serial dynamic images. Focal 18F-FDG uptake was observed in 84 foci. Of the 58 foci determined pathologically or clinically to have pathological uptake, no change was observed on serial dynamic imaging in 54 foci (sensitivity, 93%). Of the 26 foci of physiological uptake, temporal changes in uptake were observed in 20 foci using dynamic imaging (specificity, 77%). The positive and negative predictive values were 90% and 83%, respectively, with an accuracy of 88%. Dynamic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging allows for differentiation between pathological and physiological uptake in the abdominopelvic region of patients with gynecological cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) is widely used for pre-treatment staging of malignant tumors, determining responses after chemotherapy, searching for recurrence and metastasis, and predicting prognosis1,2,3. In gynecological cancers, it is clinically important to correctly diagnose lymph node metastases and peritoneal dissemination to select an appropriate treatment. Conventional static imaging is often used as a routine examination, and additional delayed images may be obtained after a period if the transition of the uptake in the target lesion is to be followed further. However, with static PET imaging, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between pathological and physiological 18F-FDG uptake, and additional delayed imaging requires extra effort and time4. In gynecological cancers with frequent recurrence or metastasis in the pelvis, it has been previously reported that physiological uptake in the ureter and bladder can mask pathological uptakes or cause false-positive results5,6,7. Some recent PET systems allow continuous bed motion for whole-body PET imaging8,9, which improves uniformity and reproducibility across the entire field of view compared to the step-and-shoot imaging mode. These improvements allow sequential dynamic imaging and may be useful for the continuous evaluation of tissue 18F-FDG counts for various quantitative analyses of tissue characteristics10,11,12.

Dynamic tracer imaging, which has recently received considerable attention, can provide more information about in vivo biology by revealing the temporal and spatial patterns of tracer uptake13,14. Nishimura et al. reported that assessing the dynamic distribution of 18F-FDG uptake could add diagnostic value to the analysis of routine static images15. In the present study, we performed dynamic whole-body imaging in patients diagnosed with gynecological cancers to evaluate the continuous visual changes in 18F-FDG uptake from the abdomen to the pelvis. These images were summed to produce high-quality whole-body images for conventional interpretation.

This present study aimed to evaluate whether dynamic whole-body PET provides additional diagnostic value compared to the conventional static whole-body imaging in patients with gynecological cancer.

Methods

Ethics

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (approval number: ERB-C-2897-1). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all methods were performed in compliance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

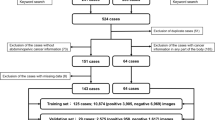

Patient selection

Sixty-one consecutive examinations for suspected gynecological malignancies or metastasis after gynecological cancer treatment performed at our institution between March 2018 and January 2020 were included (Table 1).

PET/CT imaging protocol

Prior to FDG injection, all patients fasted for at least 4 h, and their blood glucose levels were below 200 mg/dL. An automatic injector (Auto Dispensing Injector UG-05, Universal Giken Corporation, Odawara, Japan) was used to administer 3.7 MBq/kg body weight of 18F-FDG to each patient. A PET/CT system (Biograph Horizon, Siemens Healthineers) was used to perform PET/CT imaging approximately 60 min after 18F-FDG injection. Low-dose CT scans were performed to correct for PET attenuation, anatomical information, and image fusion.

Four serial dynamic whole-body 18F-FDG-PET scans were then performed by continuously moving the bed at varying speeds (6 mm/s from the head to the pelvis and 14 mm/s for the lower extremities), acquiring each whole-body phase in approximately 3 min each in the list mode. For routine image interpretation, the four dynamic phases were summed and reconstructed, equivalent to 12 min of whole-body imaging.

Dynamic whole-body PET and total-body PET images were reconstructed using a 180 × 180-pixel matrix, 5 mm post-reconstruction, an iterative algorithm with four iterations and ten subsets, application of flight time, and a Gaussian filter with attenuation-corrected normal Poisson three-dimensional ordered subset expectation maximization (3D-OSEM).

Image interpretation

Based on previous studies16,17,18, high-uptake foci with SUVmax > 2.5 on the summed image in the abdominal to pelvic region caudal to the renal portal were automatically identified. Physiological uptake included the ureter and colon, thus excluding obvious tubular ureteral and intestinal uptake.

Image analysis

At first, these foci on the summed image were evaluated in multiple directions and cross-sections and, in some cases, in the fusion and cine-loop modes. Subsequently, continuous dynamic images were evaluated in these foci. High uptake foci that disappeared during any phase or showed morphological changes in more than half of the foci were defined as “changed” uptake, and other foci were defined as “unchanged” uptake. Image interpretation was performed by two board-certified nuclear medicine physicians (with 9 and 11 years of experience in PET imaging, respectively). When the physicians’ diagnoses did not align, a final decision was reached through thorough consultation among them.

Patients’ medical records were reviewed. 18F-FDG high-uptake foci in the abdomen to the pelvis was defined as a pathological malignancy diagnosed by surgical specimens or clinical malignancy combined with other contrast CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. On the other hand, 18F-FDG physiological uptake into the ureter, intestinal tract, and endometrium was confirmed at a mean follow-up of 1547 days.

Statistical analysis

The frequency of high 18F-FDG uptake foci and changes in uptake in each group were compared using the chi-square test with Yate’s continuity correction. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy for the detection of abnormal lesions were calculated.

Results

In the present study, 84 focal high 18F-FDG uptakes were observed, with 26 physiological and 58 pathological uptakes (Table 2). All benign tumors (2 out of 2) were diagnosed pathologically. Among the malignant tumors, seven out of 56 were diagnosed pathologically, while the remaining 49 out of 56 were diagnosed clinically by integrating results from other diagnostic modalities and follow-up assessments. Twenty-two of the 26 physiological uptakes were due to ureteral hot, which accounted for the majority of false positive lesions. Changes in the morphology of uptakes were more often associated with physiological uptake (20/26, 77%) than with pathological uptake (4/58, 7%) (p < 0.01) (Table 3). Evaluation with a dynamic imaging of the focal uptake picked up on the summed image shows a phase in which the uptake clearly disappears and reappears and can be easily judged to be a physiological uptake in the ureter (Fig. 1). Among the 58 cases pathologically or clinically diagnosed with pathological uptake, 56 were malignant lesions, and two were benign tumors. Of the 56 malignant lesions, 31 were lymph node metastases, and 17 were peritoneal dissemination. Dynamic imaging indicated that 54 uptakes were “unchanged” (sensitivity, 93%). Thus, a relatively large number of pathological 18F-FDG uptakes were “unchanged” on dynamic imaging. Among 26 foci of physiological 18F-FDG uptakes, 20 were identified as “changed” in motion on dynamic imaging (specificity, 77%) (Table 3). Even when multiple localized uptakes were picked up per a single case on the summed images, it was possible, in some cases, to diagnose pathological or physiological uptake based on changes in morphology (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the absence of morphological changes or uptake movement in each phase of the dynamic images at a site that could easily be mistaken for the ureter allowed us to judge that it was a pathological uptake (Figs. 3 and 4).

Summed image, PET/CT fusion image and four serial whole-body dynamic PET images (1st − 4th, 3 min each) of a patient with cervical cancer (arrows). Two-point 18F-FDG uptakes are seen on the summed image, and a hot spot is also seen on the fusion image. 18F-FDG uptakes in ureter change (arrowheads) in the dynamic four-phase images.

Summed image and four serial whole-body dynamic PET images (1st − 4th, 3 min each) of a patient with endometrial cancer (arrows). One focal uptake is observed in the left abdomen in the summed image, and the uptake disappears in 4th phase (arrowheads). This one was clinically diagnosed as physiological uptake in the colon.

Summed image and four serial whole-body dynamic PET images (1st − 4th, 3 min each) of a patient with recurrent ovarian cancer. The summed image shows one focal hot (arrowheads). There is no change in the morphology of the uptake in the dynamic four-phase images, suggesting pathological uptake. This one was clinically diagnosed as lymph node metastasis.

The PPV and NPV were 90% and 83%, respectively. In other words, many physiological 18F-FDG-uptake foci exhibit motion changes on continuous dynamic images. The overall accuracy of differentiating pathological from physiological 18F-FDG uptake based on changes in motion on dynamic images was 88%.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined whether it is possible to differentiate between spot-like uptake in the ureter, colon, and endometrium and tumor uptake after excluding uptake that can be immediately identified as ureteral on conventional PET/CT. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use continuous dynamic PET imaging to evaluate changes in local 18F-FDG uptakes in patients with gynecological cancer.

Various methods have been proposed to differentiate between physiological and pathological uptake in PET/CT, including evaluating the intensity and location of uptake19,20,21or comparing 90–180 min delayed scans22,23,24. The clinical value of 18F-FDG-PET for identifying focal and metastatic lesions in gynecological cancer has been reported in several studies2,7,25. However, it has also been reported that pathological uptake is often masked by the ureter, bladder, and intestinal tract and false positive lesions in gynecological cancers in the pelvic region. Assessment of changes in the morphology of lesion uptake over time can help reduce false lesions caused by the ureteral and intestinal tracts, which are particularly common in the pelvis.

Ureteral uptake is a well-known potential false positive finding on PET/CT imaging21. Experienced nuclear medicine specialists can often diagnose ureteral uptake by recognizing it as a long, hot segment along the ureter in PET images and by identifying the positional relationship between the uptake and the ureter in PET/CT images. However, differentiation can be challenging for less experienced physicians. Ureteral uptake can sometimes appear as a hot spot in PET images, and in cases where the ureter is difficult to identify on PET/CT or when body motion prevents determination of the positional relationship between the hot spot and ureter, differentiation can become difficult and lead to misinterpretation as malignant tumor uptake. In the present study, we examined whether it is possible to differentiate between spot-like uptake in the ureters, colon, and endometrium and tumor uptake after excluding uptake that can be immediately identified as ureteral on conventional PET/CT.

The dynamic 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging technique offers significant advantages over static imaging in differentiating between pathological and physiological uptake in the abdominal region15,26. Each 3-min dynamic whole-body image obtained with this system had an acquisition time comparable to that of conventional static imaging while maintaining the acceptable image quality necessary for accurate assessment. The present study found that physiological uptake in regions, such as the gastrointestinal tract and ureter, frequently changed over time, whereas both benign and malignant lesions typically remained stable. This approach is particularly effective in distinguishing between pathological and physiological uptake in the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts. Furthermore, the use of serial dynamic imaging can reduce the need for cumbersome delayed scans that increase radiation exposure, thereby minimizing the need for additional imaging procedures.

Our study demonstrated that four out of 58 pathologically confirmed uptake lesions were classified as “changed”, possibly due to some motion of the disseminated lesions on the unfixed surfaces of the intestine and sigmoid colon.

This study had several limitations. First, this was a retrospective single-center study analyzing high-uptake foci with SUVmax > 2.5 in the abdominal to pelvic region, and the number of cases is limited. Prospective, preferably multicenter studies are required to confirm our preliminary results. Second, we analyzed the temporal changes in 18F-FDG uptake qualitatively and did not perform a quantitative analysis. Quantitative analysis of the changes in uptake may provide additional value in differentiating malignant from benign lesions27,28. Third, a rigorous comparison with delayed PET imaging was not performed. The usefulness of delayed scans in differentiating between benign and malignant tumors has been reported in several reports23,24,29,30. However, such delayed imaging poses several difficulties in clinical practice. Delayed imaging is only possible after 18F-FDG abnormalities are detected through conventional methods, requiring time-consuming repositioning and resulting in additional radiation exposure from a second CT scan. In contrast, dynamic whole-body scans can be performed in the same amount of time as conventional methods without additional radiation exposure. If a comparison with delayed PET imaging is performed and dynamic imaging can provide a comparable positive diagnosis rate, delayed PET imaging may be omitted in the future26. Our preliminary results indicated that the dynamic PET technique potentially provides compelling ureter differentiation capabilities.

In conclusion, dynamic whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging allows the differentiation between pathological and physiological uptake, excluding evident ureteral and intestinal uptake, in the abdominopelvic region of patients with gynecological cancer.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Fletcher, J. W. et al. Recommendations on the use of 18F-FDG PET in oncology. J. Nucl. Med. 49, 480–508 (2008).

Lazzari, R. et al. The role of [(18)F]FDG-PET/CT in staging and treatment planning for volumetric modulated Rapidarc radiotherapy in cervical cancer: experience of the European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy. Ecancermedicalscience 8, 405 (2014).

Dejanovic, D., Hansen, N. L. & Loft, A. PET/CT variants and pitfalls in gynecological cancers. Semin Nucl. Med. 51, 593–610 (2021).

Bellini, P. et al. Clinical meaning of 18F-FDG PET/CT incidental gynecological uptake: an 8 year retrospective analysis. Indian J. Gynecol. Oncolog. 19, 99 (2021).

Alvarez Moreno, E., Jimenez de la Peña, M. & Cano Alonso, R. Role of New Functional MRI Techniques in the diagnosis, staging, and followup of gynecological Cancer: comparison with PET-CT. Radiol. Res. Pract. 219546 (2012). (2012).

Williams, A. D. et al. Detection of pelvic lymph node metastases in gynecologic malignancy: a comparison of CT, MR imaging, and positron emission tomography. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 177, 343–348 (2001).

Prabhakar, H. B., Kraeft, J. J., Schorge, J. O., Scott, J. A. & Lee, S. I. FDG PET-CT of gynecologic cancers: pearls and pitfalls. Abdom. Imaging. 40, 2472–2485 (2015).

Dahlbom, M., Reed, J. & Young, J. Implementation of true continuous bed motion in 2-D and 3-D whole-body PET scanning. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 48, 1465–1469 (2001).

Osborne, D. R. et al. Quantitative and qualitative comparison of continuous bed motion and traditional step and shoot PET/CT. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 5, 56–64 (2015).

Karakatsanis, N. A., Casey, M. E., Lodge, M. A., Rahmim, A. & Zaidi, H. Whole-body direct 4D parametric PET imaging employing nested generalized Patlak expectation-maximization reconstruction. Phys. Med. Biol. 61, 5456–5485 (2016).

Ben Bouallègue, F., Vauchot, F. & Mariano-Goulart, D. Comparative assessment of linear least-squares, nonlinear least squares, and Patlak graphical method for regional and local quantitative tracer kinetic modeling in cerebral dynamic 18F-FDG PET. Med. Phys. 46, 1260–1271 (2019).

Braune, A. et al. Comparison of static 18F-FDG-PET/CT (SUV, SUR) and dynamic 18F-FDG-PET/CT (Ki) for quantification of pulmonary inflammation in acute lung injury. J. Nucl. Med. 60, 1629–1634 (2019).

Rahmim, A. et al. Dynamic whole-body PET imaging: principles, potentials and applications. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 46, 501–518 (2019).

Muzi, M. et al. Quantitative assessment of dynamic PET imaging data in cancer imaging. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30, 1203–1215 (2012).

Nishimura, M. et al. Dynamic whole-body (18)F-FDG PET for differentiating abnormal lesions from physiological uptake. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 47, 2293–2300 (2020).

Wujanto, C. et al. Does external beam radiation boost to pelvic lymph nodes improve outcomes in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer? BMC Cancer. 19, 385 (2019).

Minnaar, C. A., Baeyens, A., Ayeni, O. A., Kotzen, J. A. & Vangu, M. D. T. defining characteristics of nodal disease on PET/CT scans in patients with HIV-positive and -negative locally advanced cervical cancer in South Africa. Tomography 5, 339–345 (2019).

Lee, H. J. et al. Prognostic value of metabolic parameters determined by preoperative 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 28, e43 (2017).

Tatlidil, R., Jadvar, H., Bading, J. R. & Conti, P. S. Incidental colonic fluorodeoxyglucose uptake: correlation with colonoscopic and histopathologic findings. Radiology 224, 783–787 (2002).

Gutman, F. et al. Incidental colonic focal lesions detected by FDG PET/CT. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 185, 495–500 (2005).

Kostakoglu, L., Hardoff, R., Mirtcheva, R. & Goldsmith, S. J. PET-CT fusion imaging in differentiating physiologic from pathologic FDG uptake. RadioGraphics 24, 1411–1431 (2004).

Umeda, Y. et al. Prognostic value of dual-time-point 18F-FDG PET for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Nucl. Med. 56, 1869–1875 (2015).

Toriihara, A., Yoshida, K., Umehara, I. & Shibuya, H. Normal variants of bowel FDG uptake in dual-time-point PET/CT imaging. Ann. Nucl. Med. 25, 173–178 (2011).

Miyake, K. K., Nakamoto, Y. & Togashi, K. Dual-time-point 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with colorectal cancer: clinical value of early delayed scanning. Ann. Nucl. Med. 26, 492–500 (2012).

van Sluis, J. et al. Image quality and semi-quantitative measurements of the Siemens Biograph Vision PET/CT: initial experiences and comparison with Siemens Biograph mCT. J. Nucl. Med. 61, 129–135 (2020).

Kotani, T. et al. Comparison between dynamic whole-body FDG-PET and early-delayed imaging for the assessment of motion in focal uptake in colorectal area. Ann. Nucl. Med. 35, 1305–1311 (2021).

Karakatsanis, N. A. et al. Dynamic whole-body PET parametric imaging: I. Concept, acquisition protocol optimization and clinical application. Phys. Med. Biol. 58, 7391–7418 (2013).

Keramida, G., Gregg, S. & Peters, A. M. Intrahepatic fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose kinetics measured by least squares nonlinear computer modelling and Gjedde-Patlak-Rutland graphical analysis. Nucl. Med. Commun. 40, 675–683 (2019).

Zade, A. et al. Role of delayed imaging to differentiate intense physiological 18F FDG uptake from peritoneal deposits in patients presenting with intestinal obstruction. Clin. Nucl. Med. 37, 783–785 (2012).

Minamimoto, R. et al. Observer variation study of the assessment and diagnosis of incidental colonic FDG uptake. Ann. Nucl. Med. 27, 468–477 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Hiroshi Domoto, Koki Shirako, and Azusa Tahata (Department of Radiological Technology, University Hospital, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan) for their technical support. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was supported by Nihon Medi-Physics Co., Ltd. Kei Yamada received research grants from Doctor-NET Inc., and Nihon Medi-Physics Co., Ltd. Tomoya Kotani received research grants from Nihon Medi-Physics Co., Ltd., PDRadiopharma Inc., JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number: JP23K14898). Nagara Tamaki received JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number: JP23K07078).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yamada. S wrote the main manuscript text and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (approval number ERB-C-2897-1) approved the study.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (approval number: ERB-C-2897-1).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamada, S., Kotani, T., Tamaki, N. et al. Dynamic FDG PET/CT for differentiating focal pelvic uptake in patients with gynecological cancer. Sci Rep 14, 29499 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81236-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81236-x