Abstract

Recent research on dense multi-view image reconstruction has attracted considerable attention, due to its enhancement of applications such as 3D reconstruction, de-occlusion, depth sensing, saliency detection, and prominent object identification. This paper introduces a method for reconstructing high-density light field images, addressing the challenge of balancing angular and spatial resolution within the constraints of sensor resolution. We propose a three-stage network architecture for LF reconstruction that processes dense epipolar, spatial, and angular information efficiently. Our network processes epipolar information in the first stage, spatial information in the second stage, and angular information in the third stage. By extracting quadrilateral epipolar features from multiple directions, our model constructs a robust feature hierarchy for accurate reconstruction. We employ weight sharing in the initial stage to enhance feature quality while maintaining a compact model. Experimental results on real-world and synthetic datasets demonstrate that our approach surpasses state-of-the-art methods in both inference time and reconstruction quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The light field (LF) represents a high-dimensional function that describes the propagation of light rays through every point and in all directions within free space1,2. LF cameras capture 3D geometry in a manner that is both convenient and efficient. This is achieved by embedding 3D scene cues within 4D LF images, where two dimensions are allocated for spatial information and two dimensions are dedicated to angular information. In contrast to traditional 2D imaging, which captures a single viewpoint of a scene and results in a flat, two-dimensional image, LF imaging records multiple viewpoints of a scene, capturing both the direction and intensity of light. This capability enables LF to acquire more comprehensive spatial and depth information from our environment. The availability of this richer information facilitates the development of numerous practical applications, including post-capture refocusing3, foreground de-occlusion4, depth inference5, object segmentation6, virtual reality7, and 3D reconstruction8.

Early methods for capturing LF images involved using an array of cameras to simultaneously capture multiple viewpoints, with each camera in the array capturing the same scene from a slightly different perspective9. Another approach was to use a single camera mounted on a computer-controlled gantry to capture multiple shots in a time-sequential manner10. Due to the cost, complexity, and sometimes the limitations to static scenes of these early methods, commercial LF cameras such as Lytro Illum camera11 have earned increased attention and development in recent years. These systems utilize a micro-lens array positioned between the image sensor and the primary lens, enabling them to capture densely sampled LF images in a single shot, thus ushering in a new era for LF acquisition.

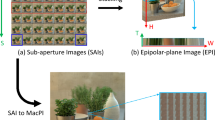

The 4D LF can be represented in various ways, such as sub-aperture images (SAIs), offer a spatially sampled perspective; epipolar-plane images (EPIs) visualize the shift in pixel values across consecutive views, revealing disparity information; and macro-pixel images (MacPIs) represent an aggregated view, capturing a broader spatial and angular context, as shown in Figure 1. Researchers choose among these representations based on the specific requirements of their methods, with each offering insights into different aspects of the LF data.

Many applications require a densely sampled LF, but achieving this is challenging due to the inherent trade-off between angular and spatial resolution in commercial LF cameras, which are often limited by sensor resolution. Researchers have sought to address this trade-off through LF image super-resolution, which aims to increase either the spatial or angular resolution of LF images. Our focus is on LF ASR, aiming to enhance angular resolution while preserving spatial resolution by reconstructing a densely sampled LF from a sparsely sampled one, thereby obtaining more views. Unlike spatial super-resolution12,13, which increases the resolution of each individual view while keeping the number of views fixed, LF ASR specifically targets the augmentation of the number of views without altering their spatial resolution.

Given the remarkable achievements of deep neural networks in image processing14,15, learning-based approaches have been proposed to tackle the reconstruction of densely sampled LF images. These learning-based methods can generally be categorized into two major classes: depth-based and non-depth-based methods.

In depth-based methods16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, depth information is initially estimated by a sub-network, which is then utilized in the depth-based warping process. This process is followed by an enhancement sub-network designed to refine the warped novel views. The enhancement step is necessary to address any errors introduced during the warping process. However, this method heavily relies on the quality of the estimated depth information, leading to distortions in areas with low-quality depth estimates due to occlusion and textureless regions. As a result, the quality of the reconstructed views may degrade.

Non-depth-based methods24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 explore the local LF information among the input views to leverage inherent correlations without relying on explicit depth information. It has achieved promising results, particularly in regions with small disparities, but it suffers from some drawbacks in regions with large disparities.

In this paper, we propose a novel non-depth-based methodology for LF reconstruction. Our approach begins by extracting high-dimensional features from a sparsely sampled LF input in four epipolar directions. These features are combined to create an initial feature set, which is subsequently processed through deep spatial convolutional blocks and a channel attention (CA) mechanism. This process enables the model to effectively learn and encode spatial geometry information, which is particularly critical for accurately rendering scenes with significant disparities. The final phase of our approach involves an ASR stage aimed at reconstructing the missing angular views to achieve a densely sampled LF. Our contributions are summarized as follows:.

-

1)

To maximize the efficient use of available information, we designed a three-stage network architecture, with each stage dedicated to processing a distinct type of data. Specifically, the first stage extracts dense epipolar information. The second stage focuses on spatial information, while the third stage addresses angular information during the angular super-resolution (ASR) process.

-

2)

Given the importance of initial feature extraction, we extract quadrilateral epipolar features to capture and represent key geometric information from multiple directions, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to build a robust feature hierarchy for more accurate reconstruction.

-

3)

Experimental results on both real-world and synthetic datasets demonstrate that our approach surpasses state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods in terms of both inference time and reconstruction quality. The structure of this document is as follows: Section II provides a concise overview of relevant studies, Section III outlines the key elements of the suggested method, Section IV showcases detailed experiments and ablation studies to confirm the effectiveness of the method proposed, and Section V concludes the paper with final observations.

Related work

The problem of LF ASR has been extensively explored over the years, resulting in two primary methodologies: non-depth-based and depth-based approaches. Non-depth-based methods exploit inherent correlations within LF data to achieve higher resolution, whereas depth-based methods utilize estimated depth information to enhance resolution. Each approach presents distinct advantages and challenges, thereby continuing to drive active research in LF imaging.

Depth-based LF ASR

Depth-based methods achieve super-resolution by warping and blending input SAIs to the target angular positions, using estimated depth information represented as disparity maps. Traditional methods include Wanner et al .16, who utilized structure tensors to derive disparity maps from EPIs and introduced a variational framework to integrate the warped views. Zhang et al .17 proposed patch-based synthesis techniques, dividing the center SAI into distinct depth layers and applying LF editing across these layers.

Numerous learning-based approaches have emerged for densely sampled LF ASR. Srinivasan et al .18 introduced a method to create a 4-D LF image from a 2-D RGB image by estimating 4-D ray depth. However, this technique requires a substantial training dataset and is limited to simple scenes due to the restricted information in a single 2-D image. Kalantari et al .19 proposed a learning-based method that divided view synthesis into two components: disparity and color estimation for novel view reconstruction. This method could synthesize high-quality views at arbitrary locations, but the disparity-based warping method led to decreased reconstruction quality in occluded and textureless regions. Salem et al .20 proposed to speed up Kalantari’s19 model with a predefined DCT filter. Choi et al .21 suggested an extreme view synthesizing method, adhering to the conventional approach of warping and refinement based on depth information. Jin et al .22 proposed using a depth information estimator with a large receptive field, followed by a refinement module to blend the warped novel views and address the challenge of large disparities. They later23 suggested reconstructing a densely sampled LF in a coarse-to-fine manner, first synthesizing coarse SAIs and then refining them using an efficient LF refinement module. They also built plane-sweep volumes (PSVs) using predefined disparity ranges to estimate disparities.

For depth-based methods, the process can be summarized in three key steps:

-

1)

Depth Estimation: The depth map \(D(x, u)\) is estimated using a function \(f_d\) from the input LF views \(L(x, u')\):

$$\begin{aligned} D(x, u) = f_d(L(x, u')) \end{aligned}$$(1) -

2)

Warping Based on Depth: A novel view \(W(x, u, u')\) at angular position \(u\) is generated by warping an input view at \(u'\) using the depth map:

$$\begin{aligned} W(x, u, u') = L(x + D(x, u)(u - u'), u') \end{aligned}$$(2) -

3)

View Refinement: The warped view is refined for accuracy using a refinement function \(f_r\) to reconstruct the final view \(\hat{L}(x, u)\):

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{L}(x, u) = W(x, u, u') + f_r(W(x, u, u')) \end{aligned}$$(3)

The reconstruction quality of these methods heavily relies on the estimated depth information. Estimating depth in occluded regions is challenging, leading to ghosting artifacts in the novel views. Additionally, maintaining photo consistency between novel views is difficult.

Non-depth-based LF angular superresolution

In this approach, researchers avoid relying on depth information for reconstruction by extracting features from EPIs or SAIs. Due to their ability to intuitively represent inherent consistency and information across one spatial and one angular dimension, several methods have been proposed to enhance angular resolution using EPIs. Vagharshakyan et al.24 transformed the EPIs into the shearlet transform domain to obtain a sparse representation. Subsequently, they introduced an inpainting technique to synthesize new views within the EPIs. Due to the under-sampling in the angular dimension, direct upsampling of the angular resolution based on EPIs can result in ghosting artifacts. Marwah et al .25 introduced a compressive LF camera architecture that enables LF reconstruction using overcomplete dictionaries. Wu et al .26,27introduced a “blur-restoration-deblur” framework to address this issue. In their approach, a specific 1D blur kernel is applied to blur and then deblur the EPIs, after which the network is tasked with super-resolving the deblurred EPIs. Since they employ a blur-deblur framework with a large kernel size, the input LFs need to have a minimum of three views in each angular direction.

Methods relying on input views include Yoon et al .28,29, who introduced distinct networks to synthesize various novel views using three different types of input pairs derived from the division of different views horizontally, vertically, and surrounding. However, their approach is confined to a single reconstruction task \((2 \times 2 \xrightarrow 3 \times 3)\) and does not consider the intrinsic structure of the LF between each view. Yeung et al .30 proposed employing spatial-angular alternating convolutions to approximate 4D convolutions and created novel views in the channel dimension. To further refine the novel views, they employed stride-2 4D convolutions to model LFs. However, since the novel views are synthesized in the channel dimension, the inter-relationships between different views are disregarded. Salem et al .31 simplified the LF reconstruction problem by converting the 4D LF into a 2D raw LF image, thereby reducing the complexity from a 4D to a 2D domain. Meng et al .32,33 suggested a two-stage framework consisting of restoration and refinement, which targets spatial and ASR. To extract spatial and angular features, they employed high-dimensional 4D convolutions and densely residual modules. Wang et al .34 introduced a disentangling mechanism to untangle complex LF data by developing domain-specific convolutions, which enables effective task-specific module design and incorporation of LF structure prior. Liu et al .35 explored multi-scale spatial-angular correlations on sparse SAIs and conducted angular SR on macro-pixel features. This led to the development of an efficient LF angular SR network, EASR, using simple 3D (2D) CNNs and reshaping operations.

For non-depth-based methods, The process can be described as follows:

Where \(f\) represents the function that reconstructs the final view \(\hat{L}(x, u)\) from the input LF views \(L(x, u')\), and \(\theta\) denotes the network parameters learned during training.

Non-depth-based methods often face significant challenges when processing LFs with large disparities. These challenges include the accurate alignment of views, the preservation of angular coherence, and maintaining high image quality across varying depth levels. Traditional techniques frequently struggle to address the geometric complexities introduced by wide disparity ranges. Furthermore, these approaches tend to underperform in regions characterized by substantial disparity variations, where they fail to capture reliable view correspondences. Consequently, aliasing artifacts may emerge in these areas, leading to a noticeable degradation in visual quality. In the subsequent section, we present a novel non-depth-based methodology designed specifically to mitigate these challenges. Our approach improves view alignment and enhances reconstruction quality without the need for depth estimation, effectively reducing aliasing artifacts and significantly improving performance in complex LF scenarios.

Methodology

Problem statement

The LF image is represented as a 4D function \(L(x, y, u, v)\), where \((x, y)\) represents the spatial dimensions and \((u, v)\) represents the angular dimensions. The primary goal of LF ASR is to enhance the angular resolution of LF images, thereby constructing densely sampled LF images, denoted as \(I_{DS} \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times S' \times T'}\), from sparsely sampled LF images, denoted as \(I_{SS} \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times S \times T}\). In this context, \((S' \times T')\) and \((S \times T)\) represent the numbers of angular views in the densely and sparsely sampled images, respectively, with \((S' > S)\) and \((T' > T)\) indicating an increase in angular resolution. Achieving this super-resolution involves the synthesis of new views, specifically \(((S' \times T') - (S \times T))\) additional views, during the reconstruction process. This problem can be implicitly formulated as \(I_{DS} = f(I_{SS})\) where, f represents the mapping function that needs to be learned. In this study, we initially transform LF images from the RGB color model to the YCbCr color space, concentrating our processing efforts on the Y channel. This conversion process is followed by upsampling the Cb and Cr channels using bicubic interpolation. After upsampling, these channels are precisely integrated with the Y channel to construct the final densely sampled LF image.

Overview architecture

The architecture of the proposed network, detailed in Figure 2, which is systematically divided into three primary stages: Initial Feature Extraction (IFE), Deep Feature Extraction (DFE), and Angular Super-Resolution (ASR). As outlined in Algorithm 1, The network takes a sparsely sampled LF image Iss as input. The IFE stage extracts high-dimensional features from LF epipolar geometries across four angular directions. These features are then combined to form an initial feature set \(F_{init} \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C \times S \times T}\). This initial feature set \(F_{init}\) is subsequently transformed into MacPI format, represented as \(\mathbb {R}^{HS\times WT \times C}\), in preparation for further processing.

Following the initial processing, the data moves to the first Deep Convolution Group (DCG), marking the beginning of the Deep Feature Extraction (DFE) phase. During this phase, the data undergoes advanced processing using deep spatial convolution, Layer-by-Layer Concatenation, and CA techniques to learn spatial geometry information, which is particularly beneficial for scenes with large disparities, resulting in the formation of \(F_{deep} \in \mathbb {R}^{HS \times WT \times C }\). After the DFE phase, the ASR stage begins, applying the PixelShuffle layer to refine the MacPI feature maps, resulting in \(F_{hr} \in \mathbb {R}^{HS' \times WT'}\).

To synthesize the final \(I_{DS}\), the network employs a global residual connection strategy. This strategic approach guarantees the enhancement of angular resolution while preserving the spatial-epipolar integrity of the LF image. The following sections will provide a detailed explanation of the key components of our network.

Initial feature extraction (IFE)

The IFE stage is responsible for extracting high-dimensional features from LF epipolar geometries across four directions: horizontal, vertical, top diagonal, and bottom diagonal, as illustrated in Figure 3. SAIs in each direction are concatenated to form four EPI stacks: horizontal (H), vertical (V), top diagonal (TD), and bottom diagonal (BD). These EPI stacks are processed in two groups for efficiency: the first group includes the H and V stacks, and the second group includes the TD and BD stacks. Within each group, shared layers are utilized. Specifically, for the first group, the V stack is transposed to match the H stack and then transposed back to its original form to facilitate subsequent addition. Similarly, for the second group, the BD stack is flipped to match the TD stack and then flipped back for subsequent addition.

Initially, each EPI stack is processed using a single 3\(\times\)3 convolutional layer. The resulting feature maps from each stack are then reshaped into the SAIs format and added together to form the pre-initial feature \(F_{pre}\). This stacking process is repeated, with each stack now processed through two 3\(\times\)3 convolutional layers separated by a leaky ReLU activation function, as illustrated in Figure 2. The feature maps extracted from each epipolar direction are reshaped into the SAIs format and added to \(F_{pre}\) to create the initial feature \(F_{init} \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C \times S \times T}\). The output of IFE stage, \(F_{init}\), can be expressed as follows:

Where IFE represents the Initial Feature Extraction process consisting of a 3\(\times\)3 convolutional layer, followed by two additional 3\(\times\)3 convolutional layers, with a leaky ReLU activation function applied between them.

Deep feature extraction (DFE)

The goal of the DFE stage is to capture spatial geometry information, including spatial texture structures, from the initial feature map by employing deep spatial convolution, Layer-by-Layer Concatenation, and CA mechanisms. The DFE stage consists of N Deep Convolution Groups (DCGs), each comprising L Deep Residual Blocks (DRBs). The output from each DCG is concatenated and processed through a CA Block, followed by a 1\(\times\)1 convolution for integrating multi-stage information. Similarly, within each DCG, the outputs of the DRBs are concatenated, processed through a CA Block, and then combined using a 1\(\times\)1 convolution for internal multi-stage information integration. In this study, N and L are set to 2 and 4, respectively. Each DRB includes a 3\(\times\)3 convolutional layer, followed by eight 3\(\times\)3 convolutional layers separated by leaky ReLU activation functions, and concludes with another 3\(\times\)3 convolutional layer. A skip connection is used after the first layer and before the final layer. For further details, see Figure 2. The output of the DFE stage is the deep feature map \(F_{deep}\), which encapsulates the spatial geometry information. It can be expressed as follows:

where DFE represents the Deep Feature Extraction process, which consists of two DCGs, each containing four DRBs. It employs Layer-by-Layer Concatenation and Channel Attention techniques.

Angular super-resolution (ASR)

After extracting deep features, the next step involves performing ASR on the MacPI feature to achieve the desired angular resolution. This process involves a down-sampling and up-sampling approach. First, a 2\(\times\)2 convolutional layer is applied to \(F_{deep}\) to generate angularly downsampled feature maps. Next, a 1\(\times\)1 convolutional layer is used to increase the channel depth, preparing these feature maps for angular upsampling. For ASR, we employ a pixel shuffling layer followed by 3\(\times\)3 and 1x1 convolutional layers separated by leaky ReLU activation functions to accommodate for the spatial distortion that occurred while upsampling. The output of the ASR stage is denoted as \(F_{hr}\), and it can be expressed as follows:

Where ASR represents the Angular Super-Resolution process. finally, to synthesize the final \(I_{DS}\), Bicubic interpolation is used to upscale the angular dimensions of \(I_{SS}\), which are then restructured into the MacPI format. A global residual connection strategy is employed to allow for the residual summation of the bicubic upscaled angular dimensions with \(F_{hr}\). This approach enhances angular resolution while preserving the spatial-epipolar integrity of the LF image. The process can be formally expressed as follows:

where BI represents the bicubic interpolation operation.

Experiments

In this section, we perform a comprehensive comparative analysis between our proposed model and SOTA methods, emphasizing key differences and advantages. Subsequently, we present detailed ablation studies to assess the impact of various modifications, illustrating the contribution of each component to overall performance. Finally, we explore the applicability of our method to depth estimation tasks.

Datasets and implementation details

For our experiments, we utilized both synthetic and real-world LF datasets to ensure a comprehensive evaluation. Specifically, we used the HCInew36and HCIold37 datasets for synthetic data, and the 30scenes19 and STFlytro38 datasets for real-world data. The training and test splits were consistent with those employed in34, involving 120 scenes for training-100 real-world scenes and 20 synthetic scenes. Our test set comprised 5 scenes from the HCIold dataset, 4 from the HCInew dataset, 30 from the 30scenes dataset, and 40 from the STFlytro dataset, subdivided into 25 Occlusions and 15 Reflective scenes to evaluate both synthetic and real-world data.

The datasets employed in this study encompass several variant factors essential for the thorough evaluation of LF reconstruction methods. Notably, the synthetic datasets are important for assessing performance on large-baseline LFs, as indicated by their disparity ranges presented in Table 1. These datasets also include high-resolution textures, which are crucial for evaluating the methods’ ability to preserve high-frequency details. To quantify texture complexity within these scenes, we utilize the texture contrast metric, calculated on the center view using the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix39. Higher texture contrast values correspond to scenes with more complex textures.

In contrast, the real-world datasets are designed to evaluate performance under natural illumination conditions and account for practical camera distortions. These datasets generally exhibit much smaller disparity ranges compared to synthetic datasets. Nevertheless, the portability of the Lytro camera facilitates the capture of diverse outdoor scenes with intricate real-world textures. As highlighted in Table 1, these scenes also exhibit high texture contrast, signifying complex textures. By addressing these varied aspects, the datasets provide a comprehensive framework for the evaluation of LF reconstruction methods, ensuring rigorous testing across a wide spectrum of scenarios and challenges.

In line with previous methods22, and34, we addressed the 2\(\times\)2 to 7\(\times\)7 ASR task. To prepare our training and test data, we first extracted the central 7\(\times\)7 SAIs and used the 2\(\times\)2 corner views as input to reconstruct the missing views. During training, each SAI was cropped into 64\(\times\)64 patches, resulting in approximately 15,000 training samples for both the real-world and synthetic datasets. For data augmentation, we applied random 90-degree rotations, as well as horizontal and vertical flips.

Our experimental setup was executed on a PC utilizing Nvidia RTX 3090 GPU. The network training incorporated the Adam optimizer40, configured with \(\beta _1\) =0.9, \(\beta _2\) =0.999, and a batch size of 4. The learning rate was initialized at \(2 \times 10^{-4}\) and subjected to a 50% reduction every 25 epochs, The model was trained for a total of 80 epochs. The entire training process, executed over 80 epochs, spanned 8 hours and 37 minutes, ensuring gradual optimization and convergence. The training process employed an \(L_1\) loss function for optimization. Given a training pair \(\{I_{GT}, I_{SS}\}\), where \(I_{GT}\) represents the ground truth LF image, the proposed network \(f\) aims to reconstruct a high-resolution LF image. The goal is to minimize the error between the network’s output and the ground truth. The loss function is formulated as:

This \(L_1\) loss quantifies the absolute pixel-wise differences between the reconstructed and ground truth LF images, guiding the network to generate more accurate and faithful reconstructions. For quantitative assessment, we employed Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), focusing specifically on the Y channel images. The evaluation involved calculating PSNR and SSIM values for each of the 45 reconstructed views in the 2\(\times\)2\(\rightarrow\)7\(\times\)7 ASR task. These values were then averaged to derive a composite score for each scene. Subsequently, the dataset score was obtained by averaging the scene scores, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of the reconstruction performance.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods

To evaluate the performance of our proposed model, we conducted a comparative analysis against five LF ASR methods. The benchmark methods included in this comparison are Kalantari et al .19, Jin et al .22, FS-GAF23, DistgASR34, and EASR35. For simplicity and consistency with existing works, we chose to conduct the 2\(\times\)2\(\rightarrow\)7\(\times\)7 ASR task. Quantitative comparisons for the 2\(\times\)2\(\rightarrow\)7\(\times\)7 task are detailed in Table 2.

Our comprehensive analysis indicates that the proposed LF reconstruction network outperforms other methods in terms of objective quality metrics. For real-world datasets, the proposed network exhibits significant enhancements in PSNR relative to depth-based methodologies, with observed average increases of 2.17 dB over Kalantari et al.19, 1.24 dB over Jin et al.22, and 1.21 dB over FS-GAF23. Similarly, for synthetic datasets, which pose greater challenges due to the large baseline, our network achieves noteworthy PSNR gains, specifically 4.93 dB over Kalantari et al.19, 2.93 dB over Jin et al.22, and 1.18 dB over FS-GAF23. In comparison to non-depth-based methods, our network also demonstrates considerable improvements. For real-world datasets, the average PSNR enhancements are 0.33 dB over DistgASR34 and 0.22 dB over EASR35. For synthetic datasets, the average PSNR increases are 2.21 dB over DistgASR34 and 1.95 dB over EASR35. Moreover, consistent improvements in the average SSIM across all test datasets further underscore the robustness and effectiveness of our proposed approach.

Figures 4 and 5 present a qualitative comparison between our method and other techniques for real-world and synthetic LF images, respectively. The visual results demonstrate that the views reconstructed by our method exhibit a higher fidelity to the ground truth. Specifically, the zoomed-in regions reconstructed by our approach retain more detailed and visually pleasing features, whereas the results from competing methods often suffer from blurring and ghosting artifacts. For instance, in the scene 30scenes_IMG_1528, the green square highlights an error on the lamppost located between the two leaves of the tree, where the distance is minimal and the lamppost is occluded in several input views. Our model is able to produce higher-quality reconstructions with clearer edges around object boundaries. Similarly, in the Occlusions_43 scene, where complex occlusions challenge many methods, our approach outperforms others by producing cleaner reconstructions with fewer artifacts, effectively handling occluded regions better than competing techniques.

Moreover, our method achieves a more precise reconstruction, as evidenced by the significantly cleaner error maps. In Figure 5, our approach is particularly effective in recovering the detailed structure of the mattress table in the HCI_old_stilllife image, and preserves the fine details of the wall painting in the HCI_new_bedroom image. This performance underscores our method’s superior ability to maintain intricate details, even in challenging scenarios characterized by large disparities.. Additionally, we provide EPIs recovered by each method for further comparison. The EPIs generated by other methods display noticeable artifacts, while our method produces EPIs with fewer artifacts and better preservation of linear structures, as shown on the horizontal EPI of HCI_new_dishes image. This demonstrates our method’s promising ability to accurately recover the LF parallax structure and enhance the overall quality of ASR.

The enhanced performance of our proposed network can be primarily attributed to two critical factors. First, the proposed network fully exploits the rich angular information inherent in LFs, utilizing a multi-stream architecture to implicitly learn geometric consistency between neighboring views and spatial texture structures. This comprehensive use of angular information significantly improves reconstruction quality. In contrast, existing methods rely on disparity-based warping techniques or neglect the available angular information. Specifically, Jin et al.22, and FS-GAF23 rely on disparity-based warping makes the reconstruction quality highly vulnerable to the accuracy of disparity estimation, particularly in occlusion regions. Furthermore, Kalantari et al.19 synthesized the target views one by one, ignoring the corresponding relationships between each novel view. Similarly, methods like DistgASR34 and EASR35 overlook the rich angular information, leading to the introduction of artifacts in occlusion or complex texture scenarios. By addressing these limitations and effectively utilizing the additional angular information, our network achieves superior reconstruction quality.

Performance in terms of memory size and inference time

In this subsection, we present a detailed comparison of inference times required for reconstructing densely sampled LF using our method and other techniques. This comparison specifically targets the 2x2 to 7x7 reconstruction task, evaluated across both real-world and synthetic datasets. All experiments were conducted on a standardized desktop setup featuring an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU, CUDA version 11.7, and cuDNN version 8.8.0. To ensure robustness, the reported inference times are averaged over five runs.

Table3 summarizes the comparative results, highlighting our method’s efficiency. Our approach reconstructs a 7\(\times\)7 LF scene in 2.43 seconds for the real-world dataset, and in 3.35 and 6.22 seconds for the synthetic datasets HCInew and HCIold, respectively. Notably, our method significantly outperforms FS-GAF23and DistgASR34 in terms of speed, largely due to the parallel processing of different EPI directions. Furthermore, the inference time of our method is competitive with those of Jin et al.22 and EASR35, while consistently delivering better reconstruction quality.

In addition to speed, the model size of our approach 2.65M is also advantageous. It is smaller than that of DistgASR34 and EASR35, and remains competitive with Jin et al.22 and FS-GAF23, all while providing better reconstruction quality. These results underscore the effectiveness of our method in balancing both speed and accuracy, making it a compelling choice for LF reconstruction tasks.

Ablation study

In this subsection, we conduct a series of experiments to assess the effectiveness of each component of the proposed method. To facilitate this evaluation, we developed and tested five different network variants. The specific details and configurations of each network are explained below:

Reducing the number of epipolar directions

To evaluate the impact of the number of directions included in the IFE stage, we trained two network variants. The first variant (i.e., Horizontal only) incorporates only one direction (horizontal). Specifically, we stacked the SAIs in the horizontal direction only and processed them using the IFE, while the second variant (i.e., Horizontal & vertical) includes two directions (horizontal and vertical). Specifically, we stacked the SAIs in the horizontal direction and also stack them in the vertical direction and process them using the IFE, As indicated in Table 4, the first variant experiences a decrease in PSNR by 0.26 dB on the 30-scenes dataset, 0.24 dB on the Occlusions dataset, and 0.52 dB on the Reflective dataset compared to our original method. Similarly, the second variant shows a decrease in PSNR by 0.07 dB on the 30-scenes dataset, 0.06 dB on the Occlusions dataset, and 0.21 dB on the Reflective dataset compared to the baseline. This decline in performance underscores the importance of incorporating multiple angular directions in the IFE stage. Including additional directions captures a broader spectrum of epipolar information, leading to a more comprehensive representation of the LF. Moreover, extracting features from multiple directions effectively captures complex geometries and spatial variations, thereby enhancing the super-resolution performance, as evidenced by the PSNR values in our original method using four epipolar directions.

Standard residual connections within DCG and across multiple DCGs

We explore the impact of substituting Layer-by-Layer Concatenation with standard residual connections within DCG and across multiple DCGs. In our modified network variant (i.e., Standard residual), instead of concatenating all DRBs within a DCG followed by a 1x1 fusion, we adopt a standard residual connection approach. Specifically, we add the input of the DCG directly to the final DRB in the group and apply the same strategy between the DCGs.as demonstrated in Table 4, this variant exhibits a decrease in PSNR by 0.22 dB, 0.34 dB, and 0.21 dB on the real-world 30 scenes, occlusions, and reflective test sets, respectively, compared to our original method. The observed decline in performance can be attributed to the advantages of the Layer-by-Layer Concatenation approach. This method, followed by fusion, effectively leverages intermediate representations, ensuring that both local and global contextual information is utilized. This comprehensive integration of information is less effectively achieved by standard residual connections, thus leading to the observed decrease in reconstruction quality.

Without CA module

To assess the effectiveness of the Attention module, we created a network variant (i.e., Without CA) in which the attention mechanism was removed. In this modified architecture, the concatenated features within a DCG and across multiple DCGs were directly fused without the attention. The results, as presented in Table 4, indicate a decrease in PSNR by 0.18 dB on the 30-scenes dataset, 0.18 dB on the Occlusions dataset, and 0.23 dB on the Reflective dataset, compared to our original method. This decline in performance underscores the importance of the attention module in our network. The attention module plays a crucial role in selectively enhancing informative features while suppressing less relevant ones through adaptive weighting. By dynamically focusing on critical information, the attention mechanism improves the model’s ability to capture essential spatial and angular details, leading to more accurate and higher-quality reconstruction results.

Without shared weight

In this network variant (i.e., Without SW), we eliminated weight sharing between the horizontal and vertical directions as well as between the top and bottom diagonals. The results, as presented in Table 4, indicate a reduction in PSNR by 0.08 dB on the 30-scenes dataset, 0.12 dB on the Occlusions dataset, and 0.15 dB on the Reflective dataset, compared to our original method. Furthermore, this variant results in a higher number of parameters, highlighting the parameter efficiency of our proposed approach. The observed decline in PSNR underscores the effectiveness of our weight-sharing strategy. By maintaining shared weights across various directions, our method provides additional regularization for the features, facilitating their alignment with the LF parallax structure. This regularization aids in capturing more accurate spatial and angular information, thereby enhancing the overall reconstruction quality.

Disparity estimation results achieved by SPO41 using LF images produced by different angular SR methods.

Application to depth estimation

The deployment of high-resolution, densely-sampled LF images has the potential to substantially improve the precision of depth estimation tasks. To validate the effectiveness of our reconstructed LF images, we conducted depth estimation experiment. Furthermore, we undertook a comparative analysis of the visual quality of depth maps derived from high-angular-resolution LFs, reconstructed using various techniques. For the depth estimation, we utilized the robust method known as the spinning parallelogram operator (SPO)41.

In our comparative study, we selected three reconstructed 7\(\times\)7 LF scenes from the synthetic dataset namely, bicycle, buddha, and herbs for comparison. The depth estimation results from the ground truth scenes were used as benchmarks for our visual comparisons, which are depicted in Figure 6. As can be seen from the figure, our method exhibited high accuracy in handling occluded regions. This indicates a higher degree of angular consistency in the LF images reconstructed by our approach. The enhanced performance can be attributed to our method’s process of initially extracting effective feature representations along quadrilateral directions, followed by the application of deep spatial residual blocks. This methodological framework effectively models the 2D disparity relationships, thereby augmenting the accuracy of depth estimation.

Conclusions

In this paper, we present a learning-based framework designed to reconstruct densely-sampled LFs. To fully exploit the rich information available in LFs, we decompose our network into three distinct stages, each targeting different types of information: epipolar, spatial, and angular. In the initial stage, our model focuses on extracting quadrilateral epipolar features and incorporates weight sharing to construct a robust feature hierarchy, enhancing reconstruction accuracy. The second stage employs deep spatial convolution, layer-by-layer concatenation, channel attention, and fusion techniques to leverage intermediate representations and refine informative features. For the final stage, we use a downsample-upsample approach to efficiently reconstruct dense LFs. Our experimental evaluations, conducted on both real-world and synthetic datasets, demonstrate that our method surpasses current state-of-the-art techniques in both inference time and reconstruction quality. The proposed framework effectively maintains the intrinsic structure and consistency across novel views.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available in the [LFASR-Qeg] repository, [https://github.com/ebrahem00/LFASR-Qeg/].

References

Levoy, M. & Hanrahan, P. Light field rendering. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, SIGGRAPH ’96, 31-42, https://doi.org/10.1145/237170.237199 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1996).

Gortler, S. J., Grzeszczuk, R., Szeliski, R. & Cohen, M. F. The lumigraph. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, SIGGRAPH ’96, 43-54, https://doi.org/10.1145/237170.237200 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1996).

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Guo, Y., Xiao, C. & An, W. Selective light field refocusing for camera arrays using bokeh rendering and superresolution. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 26, 204–208 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Deoccnet: Learning to see through foreground occlusions in light fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 118–127 (2020).

Chen, J., Hou, J., Ni, Y. & Chau, L.-P. Accurate light field depth estimation with superpixel regularization over partially occluded regions. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 27, 4889–4900 (2018).

Yücer, K., Sorkine-Hornung, A., Wang, O. & Sorkine-Hornung, O. Efficient 3d object segmentation from densely sampled light fields with applications to 3d reconstruction. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 35, 1–15 (2016).

Yu, J. A light-field journey to virtual reality. IEEE MultiMedia 24, 104–112 (2017).

Kim, C., Zimmer, H., Pritch, Y., Sorkine-Hornung, A. & Gross, M. H. Scene reconstruction from high spatio-angular resolution light fields. ACM Trans. Graph. 32, 73–1 (2013).

Wilburn, B. et al. High performance imaging using large camera arrays. In ACM siggraph 2005 papers, 765–776 (2005).

Laboratory, S. G. The (new) stanford light field archive. http://lightfield.stanford.edu. Accessed: Jun. 26, 2023.

Lytro illum. https://www.lytro.com/. Accessed: Jun. 26, 2024.

Wang, Y. et al. Ntire 2023 challenge on light field image super-resolution: Dataset, methods and results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1320–1335 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Ntire 2024 challenge on light field image super-resolution: Methods and results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 6218–6234 (2024).

Dong, C., Loy, C. C., He, K. & Tang, X. Image super-resolution using deep convolutional networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 38, 295–307 (2015).

Kim, J., Lee, J. K. & Lee, K. M. Accurate image super-resolution using very deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1646–1654 (2016).

Wanner, S. & Goldluecke, B. Variational light field analysis for disparity estimation and super-resolution. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 36, 606–619 (2013).

Zhang, F.-L. et al. Plenopatch: Patch-based plenoptic image manipulation. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 23, 1561–1573 (2016).

Srinivasan, P. P., Wang, T., Sreelal, A., Ramamoorthi, R. & Ng, R. Learning to synthesize a 4d rgbd light field from a single image. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2243–2251 (2017).

Kalantari, N. K., Wang, T.-C. & Ramamoorthi, R. Learning-based view synthesis for light field cameras. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 35, 1–10 (2016).

Salem, A., Ibrahem, H. & Kang, H.-S. Dual disparity-based novel view reconstruction for light field images using discrete cosine transform filter. IEEE Access 8, 72287–72297 (2020).

Choi, I., Gallo, O., Troccoli, A., Kim, M. H. & Kautz, J. Extreme view synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 7781–7790 (2019).

Jin, J., Hou, J., Yuan, H. & Kwong, S. Learning light field angular super-resolution via a geometry-aware network. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 34, 11141–11148 (2020).

Jin, J. et al. Deep coarse-to-fine dense light field reconstruction with flexible sampling and geometry-aware fusion. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 44, 1819–1836 (2020).

Vagharshakyan, S., Bregovic, R. & Gotchev, A. Light field reconstruction using shearlet transform. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 40, 133–147 (2017).

Marwah, K., Wetzstein, G., Bando, Y. & Raskar, R. Compressive light field photography using overcomplete dictionaries and optimized projections. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 32, 1–12 (2013).

Wu, G. et al. Light field reconstruction using deep convolutional network on epi. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 6319–6327 (2017).

Wu, G., Liu, Y., Fang, L., Dai, Q. & Chai, T. Light field reconstruction using convolutional network on epi and extended applications. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 41, 1681–1694 (2018).

Yoon, Y., Jeon, H.-G., Yoo, D., Lee, J.-Y. & So Kweon, I. Learning a deep convolutional network for light-field image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision workshops, 24–32 (2015).

Yoon, Y., Jeon, H.-G., Yoo, D., Lee, J.-Y. & Kweon, I. S. Light-field image super-resolution using convolutional neural network. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 24, 848–852 (2017).

Yeung, H. W. F., Hou, J., Chen, J., Chung, Y. Y. & Chen, X. Fast light field reconstruction with deep coarse-to-fine modeling of spatial-angular clues. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 137–152 (2018).

Salem, A., Ibrahem, H. & Kang, H.-S. Light field reconstruction using residual networks on raw images. Sensors 22, 1956 (2022).

Meng, N., So, H.K.-H., Sun, X. & Lam, E. Y. High-dimensional dense residual convolutional neural network for light field reconstruction. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 43, 873–886 (2019).

Meng, N., Wu, X., Liu, J. & Lam, E. High-order residual network for light field super-resolution. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34, 11757–11764 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Disentangling light fields for super-resolution and disparity estimation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 45, 425–443 (2022).

Liu, G., Yue, H., Wu, J. & Yang, J. Efficient light field angular super-resolution with sub-aperture feature learning and macro-pixel upsampling. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia (2022).

Honauer, K., Johannsen, O., Kondermann, D. & Goldluecke, B. A dataset and evaluation methodology for depth estimation on 4d light fields. In Computer Vision–ACCV 2016: 13th Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Taipei, Taiwan, November 20-24, 2016, Revised Selected Papers, Part III 13, 19–34 (Springer, 2017).

Wanner, S., Meister, S. & Goldluecke, B. Datasets and benchmarks for densely sampled 4d light fields. In VMV 13, 225–226 (2013).

Raj, A. S., Lowney, M., Shah, R. & Wetzstein, G. Stanford lytro light field archive. LF2016. html (2016).

Haralick, R. M., Shanmugam, K. & Dinstein, I. H. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics 610–621 (1973).

Kingma, D., Ba, L. et al. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. International Conference on Learning and Representation (ICLR) (2015).

Zhang, S., Sheng, H., Li, C., Zhang, J. & Xiong, Z. Robust depth estimation for light field via spinning parallelogram operator. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 145, 148–159 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1A5A8026986) and in part by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education under Grant 2023R1A2C1006944.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E. and A.S.; methodology, E.E. and A.S.; software, E.E. and A.S.; formal analysis, E.E. and A.S.; investigation, J.-W.S and H.-S.K.; resources, J.-W.S and H.-S.K; data curation, E.E. and A.S.; writing-original draft preparation, E.E.; writing-review and editing, E.E. and A.S. and J.-W.S and H.-S.K; validation, J.-W.S and H.-S.K.; visualization, J.-W.S and H.-S.K.; supervision, J.-W.S and H.-S.K; project administration, J.-W.S and H.-S.K.; funding acquisition, J.-W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elkady, E., Salem, A., Kang, HS. et al. Reconstructing angular light field by learning spatial features from quadrilateral epipolar geometry. Sci Rep 14, 29810 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81296-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81296-z