Abstract

Cuproptosis is a recently discovered form of regulated cell death triggered by mitochondrial copper accumulation and proteotoxic stress. Here, we provide the first evidence that glutathione (GSH), a major non-protein thiol in cells, acts as a cuproptosis inhibitor in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells. Mechanistically, GSH inhibits cuproptosis by chelating copper, contrasting its role in blocking ferroptosis by inhibiting lipid peroxidation. The classical cuproptosis inducer, ES-Cu (elesclomol plus copper), increases the protein stability of the transcription factor NFE2L2 (also known as NRF2), leading to the upregulation of gene expression of glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLM) and glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC). GCLM and GCLC are rate-limiting enzymes in GSH synthesis, and increased GSH is transported into mitochondria via the solute carrier family 25 member 39 (SLC25A39) transporter. Consequently, genetic inhibition of the NFE2L2-GSH-SLC25A39 pathway enhances cuproptosis-mediated tumor suppression in cell culture and in mouse tumor models. These findings not only reveal distinct mechanisms of GSH in inhibiting cuproptosis and ferroptosis, but also suggest a potential combination strategy to suppress PDAC tumor growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cell death is a crucial biological process for eliminating abnormal or aging cells under normal physiological conditions1. Moreover, excessive or impaired cell death can contribute to disease progression in pathological conditions. For example, tissue damage induced by ischemia-reperfusion injury may result from increased cell death, while resistance to cell death is often considered a hallmark of cancer2. Cell death occurs in various forms, each with distinct characteristics in morphology, biochemistry, and genetics3. One such form, cuproptosis, was identified in 2022 4,5. It is initiated by mitochondrial copper-induced cytotoxicity in cancer cells, triggered by the copper ionophore elesclomol in combination with copper (ES-Cu)4. Cuproptosis is characterized by ferredoxin 1 (FDX1)-dependent mitochondrial proteotoxic stress, including increased lipoylated mitochondrial proteins4. Cuproptosis differs from apoptosis, which is driven by caspase activation5. The induction of cuproptosis is emerging as a potential strategy for targeting multiple cancer cells either alone or in combination with other anticancer therapies6,7,8. However, the defense mechanisms against cuproptosis remain poorly understood.

Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide consisting of glutamate, cysteine, and glycine. It plays a crucial role in cellular antioxidant defense, detoxification processes, and the maintenance of cellular redox balance. The enzymes glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLM) and glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC) are responsible for regulating the synthesis of GSH, catalyzing its initial and rate-limiting step9. During periods of cellular stress, GSH can enter mitochondria through the solute carrier family 25 member 39 (SLC25A39)10,11. Elevated levels of GSH in tumor microenvironments contribute to cancer cell survival and drug resistance12,13. Additionally, GSH serves as a co-factor for glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) in inhibiting ferroptosis14, but its role in cuproptosis remains unknown.

NFE2 like BZIP transcription factor 2 (NFE2L2, also known as NRF2) is a transcription factor that plays a key role in regulating the cellular response to oxidative and metal stress in human diseases15. Metal stress refers to the cellular response to an excess or deficiency of metal ions, such as iron, copper, zinc, or manganese, beyond what is considered physiologically normal16. Typically, NFE2L2 expression remains relatively low due to its short half-life under normal conditions. However, various stressors can inhibit the proteasomal degradation of NFE2L2, resulting in increased protein stability. This, in turn, prompts its translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus, where it stimulates gene transcription. Elevated NFE2L2 protein stability and activity can suppress various forms of oxidative stress-induced cell death, including apoptosis and ferroptosis17,18,19,20. Nonetheless, it remains unclear whether the NFE2L2 pathway has a role in regulating cuproptosis.

In this study, we demonstrate that ES-Cu enhances NFE2L2 expression, conferring resistance to cuproptosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells. This resistance is mediated by the upregulation of GCLM and GCLC, leading to increased GSH levels. Subsequently, elevated GSH is transported into mitochondria via SLC25A39, where it chelates copper and inhibits cuproptosis. This resistance mechanism differs from the typical GSH-mediated removal of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in ferroptosis21. Our results are corroborated in xenograft PDAC mouse models, emphasizing the potential of targeting GSH synthesis and mitochondrial accumulation to enhance cuproptosis-mediated tumor suppression.

Results

Enhanced NFE2L2 protein stability and activity during cuproptosis

As NFE2L2 is known to be upregulated in iron-dependent cell death, specifically in ferroptosis17, our investigation aimed to determine whether NFE2L2 undergoes a similar upregulation during copper-induced cuproptosis. Our focus was on PDAC, a challenging tumor characterized by a low 5-year survival rate and limited treatment options compared to other solid cancers22,23. We utilized two well-established PDAC cell lines: human PANC1 and mouse KPC cells, both carrying the Kras11 and Tp53 mutations24, which are key drivers of PDAC.

During our experiments aimed at uncovering the mechanisms of cuproptosis resistance, exposure to a standard dose of ES-Cu, as previously reported4, led to a time-dependent increase in NFE2L2 protein expression (Fig. 1A). The protein expression of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1), an E3 ligase responsible for the degradation of the NFE2L2 protein25, was inhibited (Fig. 1A). The gene expression of NFE2L2 in PANC1 and KPC cells did not show a significant upregulation (Fig. 1B). This suggests that the elevated NFE2L2 expression primarily results from the inhibition of protein degradation. To confirm this hypothesis, a cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay demonstrated an extended protein half-life of NFE2L2 in PANC1 cells after ES-Cu or the proteasome inhibitor MG132 treatment (Fig. 1C). As anticipated, the NFE2L2 transcription factor activity assay demonstrated an elevated NFE2L2 activation in response to ES-Cu treatment (Fig. 1D). Image analysis confirmed NFE2L2 protein accumulation in nuclei after ES-Cu treatment (Fig. 1E).

Enhanced NFE2L2 protein stability and activity during cuproptosis. (A, B) Western blot and qPCR analyses of the expression of NFE2L2 in PDAC cells in whole cell extracts after treatment with ES-Cu (100 nM, 1:1) for 6–24 h (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus control, ANOVA test). (C) CHX chase assay of the degradation kinetics of NFE2L2 protein in PANC1 cells after treatment with CHX (50 µg/ml) in the absence or presence of 100 nM ES-Cu or 2 µM MG132 for 15–60 min (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus CHX group, ANOVA test). ACTB was used as a loading control. (D) NFE2L2 transcriptional activity assay of PDAC cells following treatment with ES-Cu (100 nM) for 6–24 h (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus control, ANOVA test). (E) Image analysis of the localization of NFE2L2 in PANC1 cells after treatment with ES-Cu for 24 h. Bar = 15 μm.

These findings suggest that cuproptosis activators can stabilize NFE2L2 protein, activating it in PDAC cells.

NFE2L2 mediates GCLM and GCLC expression during cuproptosis

Given the nuanced interplay between cuproptosis and ferroptosis, which demonstrates variability contingent upon the specific investigative context8, we proceeded to evaluate the response of specific genes within PDAC cells to ES-Cu. This assessment was undertaken due to copper known impact on ferroptosis sensitivity26, mediated in part by the transcriptional activity of NFE2L2. The primary NFE2L2-target genes implicated in ferroptosis include solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11; a component of amino acid transporter system xc−), GCLM and GCLC (enzymes involved in GSH synthesis), GPX4 and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1; antioxidant enzymes), and genes related to iron metabolism, such as ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1)27.

Among these genes, GCLM and GCLC exhibited the most pronounced upregulation upon ES-Cu treatment (Fig. 2A). In contrast, when exposed to erastin, a typical ferroptosis inducer, GCLM and GCLC expression remained relatively constant, while SLC7A11 and NQO1 were notably elevated (Fig. 2A). These findings suggest that NFE2L2 may selectively enhance the expression of specific target genes in PDAC cells in response to activators of cuproptosis or ferroptosis.

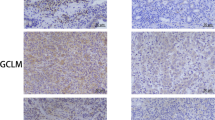

NFE2L2 mediates GCLM and GCLC expression during cuproptosis. (A) qPCR analysis of gene expression in PDAC cells following treatment with ES-Cu (100 nM) or erastin (10 µM) for 24 h. The data is displayed as a heatmap representing the mean of three biologically independent samples. (B) qPCR analysis of NFE2L2 gene expression in WT and NFE2L2-knockout (KO) cells (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus WT group, ANOVA test). (C) qPCR analysis of gene expression in PDAC cells following treatment with ES-Cu for 24 h (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus WT group, ANOVA test). (D) qPCR analysis of gene expression of NFE2L2, GCLM, or GCLC in indicated PANC1 cells following treatment with ES-Cu for 24 h (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus KO group, ANOVA test). (E) Western blot analysis of protein expression in indicated WT and NFE2L2-KO PDAC cells after treatment with ES-Cu for 24 h.

To explore the necessity of NFE2L2 in the upregulation of GCLM and GCLC mRNA expression, we employed CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing to delete NFE2L2 in both PANC1 and KPC cells (Fig. 2B). In two separate cell clones, we consistently observed that the knockout (KO) of NFE2L2 hindered the ES-Cu-induced expression of GCLM and GCLC mRNA (Fig. 2C). Overexpressing NFE2L2 cDNA in NFE2L2-KO cells confirmed GCLM and GCLC as target genes regulated by NFE2L2 during ES-Cu-induced cuproptosis (Fig. 2D). The western blot analysis confirmed that ES-Cu induced expression of GCLM, GCLC and NQO1 in wild-type cells, while showing no significant induction in NFE2L2-KO cells (Fig. 2E). In contrast, ES-Cu did not significantly alter SLC7A11 or GPX4 protein expression, regardless of NFE2L2 knockout status (Fig. 2E). In addition, ES-Cu-induced FTH1 upregulation was unaffected by NFE2L2 knockout (Fig. 2E).

Collectively, these findings suggest that NFE2L2 selectively regulates gene expression during both cuproptosis and ferroptosis, respectively.

GSH serves as a copper chelator to inhibit cuproptosis

As GCLM and GCLC are the initial enzymes in GSH synthesis, we measured intracellular GSH levels in PDAC cells. ES-Cu treatment increased GSH levels in PANC1 and KPC cells as expected (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the GSH level was downregulated in response to erastin (Fig. 3A), despite no significant changes in the expression of GCLM and GCLC (Fig. 2A). Since GSH is produced in the cytosol but is also required by the mitochondria, we assessed GSH levels in both the cytosol (“Cyt”) and mitochondria (“Mit”) following ES-Cu treatment. This assay revealed that GSH predominantly accumulated in the mitochondria of PANC1 and KPC cells (Fig. 3B). As expected, western blot analysis confirmed the expression of TUBULIN (a major component of the cytoskeleton) in the cytosolic fraction and translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOMM20) in the mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 3C).

GSH acts as a copper chelator to inhibit cuproptosis. (A) The relative levels of GSH in PDAC cells following treatment with ES-Cu (100 nM) or erastin (10 µM) for 6–24 h (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus control group, ANOVA test). (B) The relative levels of GSH in the cytosol (Cyt) and mitochondria (Mit) of PDAC cells following treatment with ES-Cu (100 nM) for 24 h (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus control group, t test). (C) Western blot analysis of TUBULIN and TOMM20 in whole cell extract (WCL), cytosolic (Cyt), and mitochondrial (Mit) fractions. (D, E) Cell vaiblity and mitochdonrial ROS (mitROS) of PDAC cells following treatment with ES-Cu (100 nM) or erastin (10 µM) in the absence or presence of N-acetylcysteine (NAC, 2.5 mM), ferrostatin-1 (1 µM), or tetrathiomolybdate (TM, 20 µM) for 24 h (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus control group, ANOVA test). (F, G) Analysis of mitochdonrial Cu+ and cell viability in PDAC cells following treatment with ES-Cu (100 nM) in the absence or presence of GSH-MEE (5 mM) or NAC (2.5 mM) for 24 h (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus ES-Cu group, ANOVA test).

GSH is a key hydrophilic antioxidant protecting cells from oxidative stress, while copper can induce ROS via the Fenton reaction28,29. However, the increased growth inhibition observed with ES-Cu was not reversed by non-enzymatic antioxidants, such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC, a GSH precursor) (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, the radical-trapping antioxidant ferrostatin-1, a well-established ferroptosis inhibitor, modestly restored cell viability by 3–5% in ES-Cu-induced growth inhibition, though this effect was not statistically significant (Fig. 3D). In contrast, tetrathiomolybdate (TM), a copper-chelating drug, reversed ES-Cu-induced growth inhibition (Fig. 3D). As a positive control, NAC or ferrostatin-1 blocked erastin-induced growth inhibition (Fig. 3D). Compared to ES-Cu, erastin increased the production of mitochondrial ROS, a response that was effectively inhibited by NAC or ferrostatin-1 (Fig. 3E). Thus, these findings suggest that ES-Cu predominantly triggers cuproptosis, rather than ROS-dependent ferroptosis in PDAC cells.

Previous studies have suggested that GSH, rather than NAC, exhibits direct copper-chelating activity in cell-free systems30. Indeed, the mitochondrial level of labile copper (Cu+) increased in NFE2L2-KO cells compared to wild-type cells after ES-Cu treatment (Fig. 3F). This effect was mitigated by GSH monoethyl ester (GSH-MEE, a cell-permeable derivative of glutathione31), rather than by low-dose NAC (Fig. 3F). Consequently, GSH-MEE, rather than low-dose NAC, reversed cell death in NFE2L2-KO cells following ES-Cu treatment (Fig. 3G).

Together, this study indicates that deficient GSH-mediated copper chelation causes increased cuproptosis in NFE2L2-KO cells.

SLC25A39 inhibits cuproptosis by transporting GSH into the mitochondria

SLC25A39 imports GSH into mitochondria10,11. We aimed to investigate if knocking out SLC25A39 through the implementation of two distinct guide RNAs (gRNAs) in PANC1 and KPC cells could potentiate cuproptosis by blocking mitochondrial GSH accumulation (Fig. 4A). Indeed, when compared to control cells, SLC25A39-KO cells displayed increased growth inhibition upon treatment with ES-Cu (Fig. 4B). As expected, the GSH levels within the mitochondria decreased (Fig. 4C), while labile Cu+ levels in mitochondria increased in SLC25A39-KO cells (Fig. 4D). These findings further support the notion that mitochondrial GSH acts as a suppressor of cuproptosis by chelating copper.

SLC25A39 inhibits cuproptosis by transporting GSH into the mitochondria. (A) Western blot analysis of SLC25A39 in WT and SLC25A39-knockout (KO) cells. (B–D) Analysis of cell viability, mitochdonrial Cu+, and mitochdonrial GSH in indicated PDAC cells following treatment with ES-Cu (100 nM) for 24 h (n = 3 biologically independent samples, *P < 0.05 versus WT group, t test). Representative bright-field images of indicated PANC1 cells treated with ES-Cu (100 nM) for 48 h. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Consistent with the cell viability assay, bright-field microscopy demonstrated that the knockout of NFE2L2 or SLC25A39 exacerbated ES-Cu-induced cell loss in PANC1 cells (Fig. 4E). Thus, NFE2L2 and SLC25A39 act as negative regulators of cuproptosis.

Targeting the GSH pathway increases sensitivity to cuproptosis in vivo

To further assess the impact of mitochondrial GSH regulation on cuproptosis sensitivity in vivo, we implanted NFE2L2-KO or SLC25A39-KO PANC1 cells subcutaneously into the right flank of immunodeficient nude mice. After one week, the tumor-bearing mice were treated with ES in the absence or presence of GSH-MEE (Fig. 5A). We didn’t use exogenous CuCl2 in vivo because ES can utilize copper produced in mice. ES decreased tumor growth in both the NFE2L2-KO and SLC25A39-KO cell groups when compared to the control group (Fig. 5B, C). Notably, ES treatment led to a localized elevation of Cu+ levels within the tumor (Fig. 5D) and serum high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (Fig. 5E), a danger signal involved in various cell death processes, including cuproptosis32,33. Conversely, GSH-MEE counteracted the inhibition of tumor growth, raised Cu+ levels within the tumor, and increased serum HMGB1 levels induced by ES in the NFE2L2-KO or SLC25A39-KO groups (Fig. 5B–E). Thus, genetic inhibition of GSH synthesis and mitochondrial import enhances the anticancer activity of ES in vivo.

Targeting the GSH pathway augments anticancer efficacy of elesclomol in vivo. (A) A schematic diagram illustrating the experimental setup where indicated PANC1 cells were injected into the flanks of nude mice. The mice were then subjected to a 3-week treatment regimen with elesclomol (ES, 50 mg/kg/ i.v., once daily, 5 days per week) in the absence or presence of GSH-MEF (10 mg/kg/p.o., once daily, 5 days per week). (B) Tumor volume change curve (n = 5 mice/group). (C–E) Tumor volume, Cu+ levels in isolated tumors, and serum HMGB1 levels in mice after 21 days of treatment (n = 5 mice/group; *P < 0.05 versus WT treatment group, ANOVA test). (F) Schematic summary of mitochondrial GSH in mediating cuproptosis resistance in PDAC cells.

Discussion

In response to heavy metal stress, cells activate defense mechanisms. In this study, we demonstrated that increased synthesis and accumulation of GSH in mitochondria inhibit cuproptotic cell death. Our findings emphasize NFE2L2 as a crucial transcription factor for limited GSH synthesis enzyme expression and highlight how blocking SLC25A39-mediated mitochondrial GSH import sensitizes PDAC cells to cuproptosis (Fig. 6). This enhances our understanding of GSH homeostasis and its role in cell death regulation34.

In normal conditions, NFE2L2 is kept low in the cytoplasm through KEAP1-mediated degradation15. When cells face oxidative stress, including metal-induced stress, KEAP1-mediated degradation of NFE2L2 is inhibited, leading to its stabilization and nuclear translocation. In the nucleus, NFE2L2 binds to the antioxidant response element in target gene promoters, initiating transcription. While we have shown that ES-Cu can enhance NFE2L2 protein stability, further investigations are required to ascertain whether sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1, a selective autophagy receptor that assists in targeting specific cellular components) mediates KEAP1 degradation25, contributing to the regulation of NFE2L2 protein stability during cuproptosis, as observed in response to ferroptotic cell death17.

Activation of NFE2L2-regulated pathways enhances the cell’s ability to combat oxidative stress and eliminate harmful substances, including metals15. In the context of cuproptosis, we showed that GCLM and GCLC are NFE2L2-targeted genes responsible for GSH synthesis. NFE2L2 also plays a crucial role in regulating the expression of enzymes related to GSH utilization, such as glutathione reductase, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione S-transferase35. Our experiments demonstrated that supplementing GSH can reverse the phenotype of NFE2L2-KO cells in response to ES-Cu. Thus, our work clearly indicates that the NFE2L2-GSH pathway plays a primary role in cuproptosis resistance in PDAC cells.

SLC25A39 encodes a mitochondrial folate transporter and was recently found to import GSH into mitochondria10,11. We revealed that GSH accumulation via SLC25A39 is vital for copper chelation, preventing cuproptosis. Copper induces ROS production but is not necessary for cuproptosis induction; it’s crucial for ferroptosis induction. GSH inhibits both cuproptosis and ferroptosis, while low-dose NAC affects only ferroptosis. This reveals how GSH distinguishes its anti-cell death roles in cuproptosis and ferroptosis, suggesting potential modulation networks involving different proteins and metal substrates of GSH in regulating cell fate.

Notably, the relationship between ferroptosis and cuproptosis is complex. While ES-Cu primarily induces cuproptosis, it may also trigger a small percentage of ferroptotic cell death. Previous studies suggest that low-dose erastin combined with copper sulfate can induce ferroptosis by promoting GPX4 degradation via the cytosolic autophagy machinery26. However, copper accumulation in mitochondria is a hallmark of cuproptosis36. Therefore, understanding the subcellular localization of copper is crucial for determining the specific type of copper-induced cell death29.

In summary, our study unveils an essential defense mechanism against cuproptosis in pancreatic cancer. Targeting the NFE2L2-GSH-SLC25A39 pathway holds promise in overcoming the development of cuproptosis resistance. Further research is needed to explore whether other NFE2L2-targeted genes are involved in regulating cuproptosis.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The antibodies for NFE2L2 (12721), KEAP1 (8047), TOMM20 (42406), TUBULIN (2144), GCLC (52183), SLC7A11 (98051 and 12691), FTH1 (3998), and ACTB (4967) were acquired from Cell Signaling Technology. The SLC25A39 antibody was obtained from Proteintech (14963-1-AP) or Thermo Fisher Scientific (PA5-42467). The GCLM antibody was obtained from Abcam (ab126704). The antibodies for GPX4 (ARC0558) and NQO1 (MA1-16672) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Erastin (S7242), N-acetylcysteine (S1623), tetrathiomolybdate (E1166), CHX (S7418), ferrostatin-1 (S7243), and elesclomol (S1052) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. GSH-MEE (G1404) and CuCl2 (222011) were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell culture and treatment

PANC1 and KPC cell lines were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection and the National Institutes of Health in the USA, respectively. They were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C under conditions of 95% humidity and 5% CO2. Cell line identity was confirmed by short tandem repeat profiling, and routine mycoplasma testing was negative. Cuproptosis induction was achieved with 100 nM ES-Cu, a combination of elesclomol and CuCl2 at a 1:1 ratio. Cell viability was assessed using a CCK-8 kit following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Gene editing and transfection

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing followed Feng Zhang’s lab protocol37. Gene editing efficiency was assessed using qPCR or Western blot analysis. Pre-designed guide RNAs (gRNAs) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich: human NFE2L2#1 (HSPD0000028069), human NFE2L2#2 (HSPD0000028071), mouse Nfe2l2#1 (MMPD0000026591), mouse Nfe2l2#2 (MMPD0000026594), human SLC25A39#1 (HSPD0000087762), human SLC25A39#2 (HSPD0000087764), mouse Slc25a39#1 (MMPD0000071924), and mouse Slc25a39#2 (MMPD0000071925). Human NFE2L2 cDNA (SC116283) was acquired from OriGene and transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s guidelines38.

Western blot

Western blotting was carried out as described previously20,39,40. In brief, proteins from cell lysates or supernatants were separated on 4-12% Criterion XT Bis-Tris gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Following blocking with 5% milk, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h at 25 °C or overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h at room temperature, and signal detection was achieved using enhanced chemiluminescence. The raw blots are presented in the supplemental information.

qPCR assay

Total RNA was extracted and purified from samples using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN)41,42. First-strand cDNA synthesis was initiated from 1 µg of RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). Specifically, 20 µl reaction mixtures were prepared by combining 4 µl of iScript Select reaction mix, 2 µl of gene-specific enhancer solution, 1 µl of reverse transcriptase, 1 µl of gene-specific assay pool (20×, 2 mM), and 12 µl of diluted RNA in RNase-free water. The resulting cDNA from various samples was then subjected to qPCR amplification using pre-designed primers from OriGene. Amplification was performed with the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Data were normalized using CFX Manager software (https://www.bio-rad.com/en-us/sku/12013758-cfx-maestro-software-2-3-for-windows-pc?ID=12013758) and fold changes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method43.

GSH and copper assay

The Mitochondria Isolation Kit (89874, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to isolate mitochondria and cytosolic extracts from cultured cells. In brief, cells (2 × 107) were pelleted by centrifugation at 850 × g for 2 min in a 2.0 mL microcentrifuge tube. After discarding the supernatant, 800 µL of Mitochondria Isolation Reagent A was added, followed by vortexing at medium speed for 5 s and incubation on ice for exactly 2 min. Next, 10 µL of Mitochondria Isolation Reagent B was added, followed by vortexing at maximum speed for 5 s and incubation on ice for 5 min, with vortexing every minute. Then, 800 µL of Mitochondria Isolation Reagent C was added, and the tube was gently inverted several times before centrifugation at 700 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to isolate the cytosol fraction. The pellet containing isolated mitochondria was resuspended in 500 µL of Mitochondria Isolation Reagent C, centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The relative purity of mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions was assessed by western blot analysis of TOMM20 and α-tubulin, respectively.

The level of GSH in whole cells, cytoplasm, or mitochondrial extracts was determined using a GSH Colorimetric Detection Kit (EIAGSHC, Thermo Fisher Scientific)44. The kit utilized a colorimetric substrate that reacts with the free thiol group of GSH, resulting in the production of a highly colored product. Oxidized GSH levels were determined by using 2-vinylpyridine (not provided) to block free GSH in the sample. Total GSH levels were obtained from untreated samples. The difference between total GSH and GSH generated from oxidized GSH in 2-vinylpyridine-treated samples determined the concentration of free GSH. GSH concentration was assessed either by measuring the color endpoint at 405 nm or by monitoring the rate of color development at 405 nm. For the analysis of Cu+ ions in the samples, we employed bathocuproinedisulfonic acid, which selectively reacts with Cu+ ions45. The formation of this complex was quantified using a spectrophotometer at a specific wavelength of 490 nm. GSH and copper levels within the mitochondria were normalized relative to the concentration of mitochondrial proteins.

NFE2L2 transcription factor activity assay

The NFE2L2 Transcription Factor Assay Kit (ab207223, Abcam) was utilized to assess NFE2L2 activity following the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay integrates a rapid ELISA format with a sensitive and specific non-radioactive method for transcription factor activation assessment. A specific double-stranded DNA sequence containing the NFE2L2 consensus binding site (5’ – GTCACAGTGACTCAGCAGAATCTG – 3’) was immobilized onto a 96-well plate. Active NFE2L2 present in the nucleus specifically binds to the oligonucleotide. NFE2L2 was detected using a primary antibody recognizing an epitope of NFE2L2 accessible only when the protein was activated and bound to its target DNA. A sensitive colorimetric readout at 450 nm was provided by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

CHX-chase analysis

PANC1 cells were pre-incubated with or without 100 nM ES-Cu or 2 µM MG132 for 12 h, followed by the addition of 50 µg/ml CHX to halt protein synthesis46,47. Cells were collected at 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min after CHX treatment. Total protein was analyzed via western blot and quantified using densitometry.

Mitochondrial ROS analysis

The quantification of mitochondrial ROS production was conducted via flow cytometry employing the MitoSOX Red Mitochondrial Superoxide Indicator (M36008, Thermo Fisher Scientific)48,49. Following the indicated treatment, cells were subjected to a 10-minute incubation with 5 µM MitoSOX at 37 °C, subsequent to which fluorescence intensity was assessed using a microplate reader (TECAN) at absorption/emission peaks approximately around 396/610 nm.

HMGB1 analysis

ELISA assays were conducted to measure HMGB1 in serum using a kit from Sino-Test Corporation (326054329) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Cells were cultured on glass coverslips, fixed with 3% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, and then treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at 25 °C for detergent extraction. Following this, coverslips were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and subjected to immunofluorescence staining using an NFE2L2 antibody, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated IgG. Images were acquired using an immunofluorescence microscope.

Animals experiment

We followed the guidelines of ARRIVE (https://arriveguidelines.org) and obtained approval from the institutional animal care and use committee (Guangzhou Medical University [S2023-786]) for all animal experiments. The mice were kept in standard housing conditions, following a 12-hour light/dark cycle (with lights on from 7:00 to 19:00), at a room temperature ranging from 20 to 25 °C, and with a relative humidity maintained between 40% and 60%. They had unlimited access to food and water. All experiments were carried out in pathogen-free facilities, and the health of the mouse colonies was routinely monitored by veterinary professionals. To ensure experimental consistency, littermates of the same sex were randomly chosen and matched for both age and body weight. We induced murine subcutaneous tumors by injecting 5 × 106 PANC1 cells in 100 µl PBS into the right dorsal midline of 8-week-old female athymic nude mice50. Once the tumors reached ~ 80 mm3 on day 7, mice were randomly grouped and treated with elesclomol (50 mg/kg, i.v., once daily, 5 days per week) with or without GSH-MEF (10 mg/kg, p.o., once daily, 5 days per week) for 3 weeks. Tumor volumes were calculated using the formula length × width2 × π/6. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Anesthesia and euthanasia were performed using 3% isoflurane and carbon dioxide inhalation, respectively, in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/s/). We employed a standard two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA for calculations. A significance level of p < 0.05 was applied to determine statistical significance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ES-Cu:

-

Elesclomol plus copper

- FDX1:

-

Ferredoxin 1

- FTH1:

-

Ferritin heavy chain 1

- GCLC:

-

Glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit

- GCLM:

-

Glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- GPX4:

-

Glutathione peroxidase 4

- KEAP1:

-

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- NFE2L2:

-

NFE2 like BZIP transcription factor 2

- NQO1:

-

NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1

- PDAC:

-

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SLC25A39:

-

Solute carrier family 25 member 39

- SLC7A11:

-

Solute carrier family 7 member 11

References

Chen, R., Zou, J., Kang, R. & Tang, D. The redox protein HMGB1 in cell death and cancer. Antioxid. Redox Signal. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2023.0007 (2023).

Kayagaki, N., Webster, J. D. & Newton, K. Control of Cell Death in Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 19, 157–180. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-051022-014433 (2024).

Tang, D., Kang, R., Berghe, T. V., Vandenabeele, P. & Kroemer, G. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell. Res. 29, 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-019-0164-5 (2019).

Tsvetkov, P. et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science 375, 1254–1261. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abf0529 (2022).

Chen, R. et al. HMGB1 in the interplay between autophagy and apoptosis in cancer. Cancer Lett. 581, 216494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216494 (2024).

Sun, L. et al. Lactylation of METTL16 promotes cuproptosis via m(6)A-modification on FDX1 mRNA in gastric cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 6523. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42025-8 (2023).

Yang, W. et al. 4-Octyl itaconate inhibits aerobic glycolysis by targeting GAPDH to promote cuproptosis in colorectal cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 159, 114301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114301 (2023).

Tang, D., Kroemer, G. & Kang, R. Targeting cuproplasia and cuproptosis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-024-00876-0 (2024).

Franklin, C. C. et al. Structure, function, and post-translational regulation of the catalytic and modifier subunits of glutamate cysteine ligase. Mol. Aspects Med. 30, 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.009 (2009).

Wang, Y. et al. SLC25A39 is necessary for mitochondrial glutathione import in mammalian cells. Nature 599, 136–140. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04025-w (2021).

Shi, X. et al. Combinatorial GxGxE CRISPR screen identifies SLC25A39 in mitochondrial glutathione transport linking iron homeostasis to OXPHOS. Nat. Commun. 13, 2483. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30126-9 (2022).

Han, L. et al. Macroautophagy/autophagy promotes resistance to KRAS(G12D)-targeted therapy through glutathione synthesis. Cancer Lett. 604, 217258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2024.217258 (2024).

Bansal, A. & Simon, M. C. Glutathione metabolism in cancer progression and treatment resistance. J. Cell. Biol. 217, 2291–2298. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201804161 (2018).

Xie, Y., Kang, R., Klionsky, D. J. & Tang, D. GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2023.2218764 (2023).

Tang, D. & Kang, R. NFE2L2 and ferroptosis resistance in cancer therapy. Cancer Drug Resist. 7, 41. https://doi.org/10.20517/cdr.2024.123 (2024).

Hall, J. L. Cellular mechanisms for heavy metal detoxification and tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 1–11 (2002).

Sun, X. et al. Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology 63, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28251 (2016).

Niture, S. K. & Jaiswal, A. K. Nrf2 protein up-regulates antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and prevents cellular apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 9873–9886. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.312694 (2012).

Sun, X. et al. Metallothionein-1G facilitates sorafenib resistance through inhibition of ferroptosis. Hepatology 64, 488–500. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28574 (2016).

Kuang, F., Liu, J., Xie, Y., Tang, D. & Kang, R. MGST1 is a redox-sensitive repressor of ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell. Chem. Biol. 28, 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.01.006 (2021). e765.

Dai, E. et al. A guideline on the molecular ecosystem regulating ferroptosis. Nat. Cell. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-024-01360-8 (2024).

Chen, X., Zeh, H. J., Kang, R., Kroemer, G. & Tang, D. Cell death in pancreatic cancer: from pathogenesis to therapy. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 804–823. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00486-6 (2021).

Halbrook, C. J., Lyssiotis, C. A., Pasca di Magliano, M. & Maitra, A. Pancreatic cancer: advances and challenges. Cell 186, 1729–1754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.02.014 (2023).

Song, X. et al. JTC801 induces pH-dependent death specifically in Cancer cells and slows growth of tumors in mice. Gastroenterology 154, 1480–1493. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.004 (2018).

Ichimura, Y. et al. Phosphorylation of p62 activates the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway during selective autophagy. Mol. Cell. 51, 618–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.003 (2013).

Xue, Q. et al. Copper-dependent autophagic degradation of GPX4 drives ferroptosis. Autophagy 19, 1982–1996. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2023.2165323 (2023).

Lane, D. J. R., Alves, F., Ayton, S. & Bush, A. I. striking a NRF2: the rusty and rancid vulnerabilities toward ferroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2023.0318 (2023).

Angele-Martinez, C., Nguyen, K. V., Ameer, F. S., Anker, J. N. & Brumaghim, J. L. Reactive oxygen species generation by copper(II) oxide nanoparticles determined by DNA damage assays and EPR spectroscopy. Nanotoxicology 11, 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/17435390.2017.1293750 (2017).

Xue, Q. et al. Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy. Autophagy 19, 2175–2195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2023.2200554 (2023).

Freedman, J. H., Ciriolo, M. R. & Peisach, J. The role of glutathione in copper metabolism and toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 5598–5605 (1989).

Chung, B. Y. et al. The glutathione derivative, GSH Monoethyl Ester, May effectively Whiten skin but GSH does not. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17050629 (2016).

Tang, D., Kang, R., Zeh, H. J. & Lotze, M. T. The multifunctional protein HMGB1: 50 years of discovery. Nat. Rev. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-023-00894-6 (2023).

Liu, J., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Kang, R. & Tang, D. HMGB1 is a mediator of cuproptosis-related sterile inflammation. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 10, 996307. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.996307 (2022).

Franco, R. & Cidlowski, J. A. Glutathione efflux and cell death. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 1694–1713. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2012.4553 (2012).

de la Rojo, M., Chapman, E. & Zhang, D. D. NRF2 and the hallmarks of Cancer. Cancer Cell. 34, 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.022 (2018).

Tang, D., Chen, X. & Kroemer, G. Cuproptosis: a copper-triggered modality of mitochondrial cell death. Cell. Res. 32, 417–418. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-022-00653-7 (2022).

Ran, F. A. et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.143 (2013).

Chen, R. et al. cAMP metabolism controls caspase-11 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in sepsis. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav5562. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav5562 (2019).

Zeng, L. et al. ALK is a therapeutic target for lethal sepsis. Sci. Transl Med. 9 https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aan5689 (2017).

Yang, M. et al. Chloroquine inhibits HMGB1 inflammatory signaling and protects mice from lethal sepsis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 86, 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2013.05.013 (2013).

Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, J., Kang, R. & Tang, D. NEDD4L-mediated LTF protein degradation limits ferroptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 531, 581–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.07.032 (2020).

Chen, R. C. et al. The role of HMGB1-RAGE axis in migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 390, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-014-1978-6 (2014).

Kang, R. et al. Intracellular HMGB1 as a novel tumor suppressor of pancreatic cancer. Cell. Res. 27, 916–932. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2017.51 (2017).

Song, X. et al. PDK4 dictates metabolic resistance to ferroptosis by suppressing pyruvate oxidation and fatty acid synthesis. Cell. Rep. 34, 108767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108767 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. A novel method of rapid detection for heavy metal copper ion via a specific copper chelator bathocuproinedisulfonic acid disodium salt. Sci. Rep. 13, 10761. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37838-y (2023).

Chen, F., Zhu, S., Kang, R., Tang, D. & Liu, J. ATP6V0D1 promotes alkaliptosis by blocking STAT3-mediated lysosomal pH homeostasis. Cell. Rep. 42, 111911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111911 (2023).

Liu, K. et al. HSP90 mediates IFNgamma-Induced Adaptive Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 82, 2003–2018. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-3917 (2022).

Battaglia, A. M. et al. Iron affects the sphere-forming ability of ovarian cancer cells in non-adherent culture conditions. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 11, 1272667. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2023.1272667 (2023).

Tang, D. et al. High-mobility group box 1 is essential for mitochondrial quality control. Cell. Metab. 13, 701–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.008 (2011).

Han, L. et al. SMG9 drives ferroptosis by directly inhibiting GPX4 degradation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 567, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.06.038 (2021).

Acknowledgements

J.L. was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200594 and 82372152).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., H.T., F.C., C.L., and Y.X. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.L. and D.T. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. R.K. assisted in data interpretation, edited the manuscript, and provided reagents. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Tang, H., Chen, F. et al. NFE2L2 and SLC25A39 drive cuproptosis resistance through GSH metabolism. Sci Rep 14, 29579 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81317-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81317-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Harnessing Cuproptosis resistance to advance cancer therapeutics

Apoptosis (2026)

-

SLC25A39 identified as a key regulator of hepatocellular carcinoma progression through the mitochondrial ROS–cytochrome c–caspase signaling axis

Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters (2025)

-

Targeting ferroptosis and cuproptosis in gastrointestinal cancers: molecular mechanisms, metabolic vulnerabilities, and therapeutic interventions

Molecular Biomedicine (2025)

-

The interactions of copper, glutamate, and cuproptosis: insights into brain health and Alzheimer’s disease pathology

BioMetals (2025)

-

Excessive glutathione intake contributes to chemotherapy resistance in breast cancer: a propensity score matching analysis

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2024)