Abstract

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is vital for the healthy function of the retina. Cellular level changes in the RPE are not visualized with current clinical techniques due to a lack of spatial resolution. Fluorescence adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscopy (AOSLO) can image RPE cells by utilizing their intrinsic autofluorescence (AF). The RPE AF has been imaged with only a few discrete excitation and emission bands and the multi-spectral AF has not been interrogated systematically at the level of single cells. In this study, we imaged 16 healthy eyes (ages 20-75) with AOSLO to investigate the multi-spectral AF as a function of age and wavelength with excitation from 650 - 805 nm. Quantitative analysis showed that 720 nm light produced images with the highest SNR (65.0 dB). Spatial AF variability showed a trend to increase with aging, suggesting increased heterogeneity in RPE AF with age. Spatial variability in the multi-spectral fluorescence of RPE cells with age may be a consequence of normal age-related loss of RPE cells. Multi-spectral fluorescence AOSLO provides new insight into aging related changes to RPE cells and may be a useful tool for studying diseases that affect the RPE, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) serves many roles that are vital to maintaining the healthy function of the retina and importantly the overlying photoreceptor cells1,2,3,4. The phagocytic, antioxidant, and blood-retinal barrier functions serve to maintain the healthy function of the photoreceptors1. The RPE also absorbs stray light, preventing potential damage to the retina1. Dysfunction and degeneration of the RPE are observed in retinal degenerative diseases such as age-related macular degeneration5,6,7,8,9(AMD), retinitis pigmentosa10,11, and Stargardt’s disease12,13. Imaging the RPE can help clinicians to understand the structural changes that occur in the eyes of patients with retinal diseases.

Clinical OCT imaging is routinely used to evaluate the structure of the RPE at the tissue level14. Spectral domain OCT b-scans are used to evaluate the structural integrity of the retina as they provide a cross-sectional perspective15. Fundus autofluorescence (FAF), in scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO), is another clinical imaging modality used to provide an overall evaluation of disease status and progression involving the RPE7,16,17,18. FAF utilizes the autofluorescence (AF) signal from the RPE, primarily from lipofuscin and melanin. FAF is usually performed with either blue (i.e. 488 nm)19or green light (i.e. 532 nm) for excitation, but more recently, NIR light (e.g. 787 nm) has been utilized20. Furthermore, clinicians commonly evaluate the FAF qualitatively, leading to subjective analysis of the data.

FAF and OCT lack the resolution to investigate the AF features of the RPE at the cellular scale. We hypothesize that subtle changes in the RPE are undetectable with current clinical imaging techniques due to the lack of spatial resolution. Cellular resolution of the RPE offers the possibility to monitor minute changes in the morphology and the AF properties of the RPE with higher sensitivity to changes over time compared to the conventional clinical devices. These minute changes could be beneficial for clinicians to monitor patients and administer care. There is a need for an objective, quantitative metric that clinicians can use to formulate definitive conclusions around the health of the RPE.

It is thought that the AF signal originates from lipofuscin when exciting the RPE with visible light21,22,23and melanin when exciting with near-infrared (NIR) light20. For the purposes of this report, we will consider wavelengths less than 700 nm to be visible or short-wavelength (SW) light and wavelengths from 700–1000 nm to be considered NIR light. However, evidence shown by Taubitz et al.24. suggests that the AF signal contribution is not as clear-cut as once thought. This study showed evidence suggesting that lipofuscin organelles in younger eyes are only excitable at SW, but in older eyes, lipofuscin exhibits both SW and NIR-AF24. They hypothesized that NIR-AF arises with aging due to the incorporation of oxidized melanin degradation products into the lipofuscin organelles. There are also observations of increase NIR-AF intensities when SW-AF increases such as in recessive Stargardt’s disease25. There are other uncertainties around the origin of the AF signal such as the spectral overlap between lipofuscin and melanin. It is known that lipofuscin can be optimally excited with \(\sim\)510 nm and has peak emission at \(\sim\)630 nm21. The fluorescence excitation and emission of ocular melanin has not been fully characterized. However, melanin can be excited with NIR light, but melanin absorption increases with decreasing wavelength20. For this reason, there likely exists some overlap in the visible spectrum between their excitation bands20.

Adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (AOSLO) enables cellular-level imaging in the living human eye by utilizing a closed-loop adaptive optics system to correct the wavefront aberrations of the human eye along with residual aberrations from the system26. Individual RPE cells have been imaged with AOSLO with back-scattered light27, AF detection28, dark field imaging29, and indocyanine green (ICG) ophthalmoscopy30. RPE cell imaging with back-scattered light was possible only in patients with rod-cone dystrophy in retinal locations where the photoreceptors were missing27. Dark field imaging had low efficacy of imaging individual RPE cells across the retina. This resulted in low-contrast images and difficulty of RPE cell segmentation. ICG ophthalmoscopy is an invasive modality, making it undesirable for the purposes of routine imaging. AF-AOSLO has been used to image individual RPE cells with both visible and NIR light27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35with higher contrast than these other methods. NIR light is preferable for RPE AF imaging because it is safer and more comfortable compared to visible light which has the potential to cause photochemical damage to the retina and appears uncomfortably bright. Furthermore, there is a large difference in the longitudinal chromatic aberration between the excitation and emission when utilizing SW light, making it difficult to focus the excitation light and detect the emitted AF signal. It is easier with NIR light because there is less longitudinal chromatic aberration between the excitation and emission36. However, NIRAF is less efficient than short-wavelength AF (SWAF)20, posing difficulty for routine imaging of RPE cells. Imaging the RPE has been proven challenging even among young, healthy participants with whom ophthalmic imaging is typically easier. Older eyes present additional challenges such as cataracts, small pupils, increased scatter, and lens opacity. Technological advancements are required for robust RPE cell imaging across all cohorts, including patients with diseased eyes as they are not only the most interesting, but also the most challenging to image.

We used fluorescence AOSLO to image individual RPE cells across a range of ages and retinal eccentricities. Our overarching goal was to determine the best configuration for imaging individual RPE cells across younger and older eyes and to understand if there was any shift in the best excitation band with age or eccentricity. We also aimed to better understand the spatial variability in the AF signal within individual cells as a function of age. We hypothesized, based on the results from Taubitz et. al., that we would detect more spatial colocalization of the signal between the shorter and longer wavelengths in the older eyes due to lipofuscin organelles being AF in the NIR in older eyes24.

Methods

Participants

16 right eyes from 16 healthy participants (age: 20–73 years) were imaged in vivo using AOSLO. These 16 participants were divided into 3 age groups: young (18–39), middle (40–59), and old (60+). All participants were confirmed to have normal healthy retinas based on results from a comprehensive eye exam and clinical multi-modal imaging including spectral domain OCT, scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (Spectralis HRA+OCT, Heidelberg Engineering, Germany), and color fundus photography, which were reviewed by clinicians at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. To ensure acquisition of quantifiable AOSLO images, the 16 participants were selected from a larger cross-sectional study where high quality AOSLO images were acquired. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The experiments were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were compensated for their participation after each imaging session.

Participants recruited for this study were imaged with 8 unique excitation wavelength bands over 4 imaging sessions with each session lasting approximately 90 minutes. One drop each of phenylephrine hydrochloride (2.5%) and tropicamide (1%) were administered 15 minutes prior to imaging for mydriasis and cycloplegia. The power of the light was variable based on wavelength to ensure that it was within the bounds of the ANSI standard guidelines37. Head stabilization was maintained using a custom chin and forehead rest38 and the eye pupil was aligned to the AOSLO transversely and axially via motors controlled by the experimenter. The participants were tasked to fixate on a target that was coupled with the imaging light with a projector. The experimenter was able to move the target under computer control. Along with fixation, a steering mirror was used to redirect the imaging light across the retina to image retinal locations unachievable with fixation alone.

Pittsburgh AOSLO

The AOSLO located at the University of Pittsburgh has been previously described35,39 (schematic diagram shown in Fig. 1). Briefly, it uses a super-continuum light source (SuperK FIANIUM FIR-20, NKT Photonics, Denmark) for illumination and a 909nm laser diode for wavefront sensing (WFS). A tunable filter (SuperK VARIA, NKT Photonics, Denmark) was used to select the excitation center wavelength and bandwidth; a 20 nm bandwidth was used for each excitation band. The Pittsburgh AOSLO acquired retinal images with a field of view of \(1.5^{\circ }\)x\(1.5^{\circ }\)across three modalities simultaneously: confocal, multi-offset, and AF across 8 channels. The confocal and multi-offset signals were collected with a custom-built 7-fiber optical fiber bundle39. The central fiber served as the confocal aperture and the 6 radially offset fibers served as apertures for multiply scattered light. AF signal detection was accomplished using a confocal aperture attached to a PMT (H7422-50, Hamamatsu, Japan) which was mounted on an x, y, z motorized stage for precise alignment. The confocal and AF signals were the primary focus of this study.

Multi-spectral AF AOSLO Imaging Protocol

Imaging protocol. All participants were imaged using center wavelengths of 660, 680, 700, 720, 740, 760, 780, and 795 nm. For each excitation wavelength, different sets of dichroic mirrors and filters were used (shown in Table 1).

Images were acquired starting from the fovea to \(12^{\circ }\) temporal with \(1^{\circ }\) step sizes. This step size overlapped adjacent images to allow for the creation of a contiguous montage of the retina along the horizontal meridian The overlapping fields of view from the fovea to \(12^{\circ }\) temporal were obtained and were later stitched together to generate the montage. The decision of imaging temporally rather than nasally was based on the results of the work done by Granger et al33where they showed the lowest variability of RPE images temporally compared to the nasal retina and within 2 mm of the fovea. They hypothesized that this was due to increased absorption and scatter due to melanin, vasculature, and/or the nerve fiber bundles33. The wavelength of light used during each imaging session was randomly assigned to all participants. Each participant was imaged with two excitation bands per imaging session and imaged across four days to minimize cumulative light exposure. Upon acquiring the images with the first imaging wavelength, the participants were asked to move to another room while the experimenter reconfigured the AOSLO to image with the second wavelength due to required alterations of optical components.

AOSLO optical configurations for AF imaging. We adjusted the focus of the excitation light to compensate for ocular longitudinal chromatic aberration. This was carried out by adjusting the position of the focusing optics following the laser fiber. The exact adjustments required were empirically determined before any human imaging was performed and testing was performed on a model eye. The initial adjustment distance was determined by utilizing the results of the longitudinal chromatic aberration of the eye from a previous study36. Once this distance was dialed via a precise motorized translation stage, final adjustments were made by qualitatively observing the image quality from the AOSLO system. Slight changes were made to ensure acquisition of high contrast images and high signal throughput to the detectors. The exact position of the focusing optics on the motorized translation stage was noted for each wavelength and was adjusted accordingly prior to imaging.

The imaging light and WFS beacon were checked for coaxiality when altering the wavelength of the imaging light. Coaxiality between the two light sources was confirmed with respect to the WFS beacon. The coaxial alignment was performed using two cameras as reference points for the WFS beacon. Once the lateral position of the WFS beacon was marked on the computer, the position of the imaging light was adjusted by iteratively adjusting the angle of two mirrors mounted on kinematic mirror mounts to match the WFS beacon’s position.

When we interchanged the dichroic mirror used to separate the confocal and AF signal, the optical beam path reflected off the dichroir mirror was redirected. For ease of replacement, dichroic mirrors were mounted on magnetic bases, eliminating the need for coarse alignment. The fiber bundle, used for confocal imaging, and AF PMT were mounted on motorized translation stages. This enabled fine, precise alignment of their lateral and axial positions via software. Detector positioning was automated using the Nelder-Mead algorithm40. The position of the fiber bundle was optimized using the mean pixel value whereas the position of the AF PMT was optimized using the number of saturated pixels per frame. AF data acquired from the AOSLO visually appears as noise and for this reason, the mean pixel value of the frame is not as effective of a metric to use for signal optimization. Saturated pixels in each frame are a better representation of the AF signal from the RPE cells. Once the optical components were replaced appropriately and the detectors were aligned, the participant was called back into the room and imaged with the same protocol.

Data processing pipeline

Image registration.

The recorded AOSLO videos were rectified to correct the sinusoidal distortion and co-registered to generate images using REMMIDE41, an in-house custom registration software that uses a strip-based image registration method. Eye motion was extracted from the AOSLO confocal video and used to register31 the AF data. Montages of the RPE cells from the fovea to \(12^{\circ }\)temporal were generated using a previously published method42. The adjacent images from the generated montages were blended using Adobe Photoshop (Photoshop, Adobe Systems Inc., USA). To compare the spatial variability in AF signal across spectral bands, we registered the eight averaged AF images together using a three-step process. For the initial registration of these images, a previously published method to montage and/or register AOSLO images42was used. This method of registration allows for coarse translational and rotational registration. The second step utilized a sub-pixel registration method to achieve fine registration to within a small fraction of a pixel43. The third and final step used an affine registration (“affine2d” function in MATLAB) to account for any remaining transformations (i.e., rotation, magnification, etc.). The hyperparameters of the affine registration were tuned empirically to balance computation time and registration precision. This three-step process provided reliable and robust registration of the RPE cells which was used for cell-by-cell AF data analysis. Once this three-step process was completed, we performed analysis of the spatial variability in the AF signal across the spectral bands at the pixel level. The variability of the AF signal across spectral bands was analyzed by averaging the variability of the pixels within a single RPE cell. Precise RPE cell segmentation was required for this analysis.

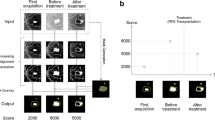

Cell segmentation via Cellpose. A well-established cell segmentation tool called Cellpose44 was used to facilitate the segmentation. Cellpose uses a deep learning approach that learns the features of the cells from the training data to segment them. We tested all of the existing models from Cellpose with our data and obtained the best results with the “cyto2” model (shown in the middle panel of Fig. 2). Based on this testing, we determined that a better result could only be obtained by re-training and generating a new model for the segmentation of our data. Due to the poor segmentation, we retrained the cyto2 model from Cellpose for better segmentation. Firstly, we semi-automatically labeled AOSLO images using the best RPE images because deep learning models train better with high quality training data. The images used were the high contrast average images from a single participant from the fovea to \(12^{\circ }\) temporal. To facilitate the labeling process, a Gabor filter was applied to these images to enhance the edge features of the RPE cells. These Gabor-filtered high contrast average images were passed through the cyto2 model from Cellpose and the labels generated from the model were used as a starting point. A highly-experienced experimenter, who has examined and analyzed hundreds of AOSLO RPE images, corrected the labels to generate ground truth labels for each image. These corrected labels from the high contrast multi-spectral averaged images were then applied to each of the eight individual lower SNR images. This resulted in a training dataset with 104 total images, totalling approximately 56,000 RPE cells. The cyto2 model was re-trained with the newly labeled images. The results from the re-trained model can be seen on the right panel in Fig. 2. Cell-based analysis was performed utilizing the segmentation of the RPE cells.

Performance of the RPE cell segmentation tool (Cellpose) from a 20 y.o. female at the fovea. Left: High contrast average image. Middle: Segmentation of the RPE cells produced using one of the pre-built models from Cellpose. Right: Segmentation of the RPE cells after re-training the model from Cellpose.

Data analysis at cellular scale. The AF variance across excitation wavelength bands and retinal locations was calculated using the normalized images of the RPE cells. Due to factors such as the differences in excitation efficiency of the fluorophores within the RPE and their spatial distribution across age, there may be colocalization of AF signal across the different excitation wavelength bands. To further investigate the homogeneity or heterogeneity of the AF signal across spectrum, the variance of the pixel intensity was calculated across wavelength bands at each retinal location for all participants. The AF variance for individual RPE cells was calculated by averaging the variance of the pixel associated with that cell (as shown in Fig. 3). The overall AF variance of the RPE was compared across age, eccentricity, and wavelength.

Illustration of the workflow for the cell-based AF variability analysis. The images shown here are from the fovea of a 20 y.o. female. (a): Stacked images of the RPE cells from the 8 different wavelength bands. (b): Heatmap of the AF variance at the pixel level. (c): Heatmap of the AF variance at the cellular level. The color bar is associated to the pixel and cellular level heatmaps.

Results

Quantification of image quality

The montages of the RPE cells from a 20 year old (y.o.) female, from the fovea to \(12^{\circ }\) temporal, can be seen in Fig. 4. The fovea is positioned on the right of the montages. The RPE cells in the montages appeared with a hyper-fluorescent border and a hypo-fluorescent center. Qualitatively, the contrast and intensity of the RPE cells varied across wavelength. The RPE cells appeared more defined around the fovea and towards \(12^{\circ }\) temporal whereas the RPE cells appeared noisier in the intermediate eccentricities (\(\sim\) \(6^{\circ }\)temporal). This observation was more evident in the 795 and 660 nm montages. Also, intermediate wavelengths had higher contrast and brightness compared to the longest and shortest wavelengths tested. Additionally, the longer wavelengths resolve some RPE cells that lie beneath the blood vessels as longer wavelengths have greater penetration through the blood compared to the shorter wavelengths33.

We quantitatively evaluated the image quality of AOSLO RPE cell images using a previous method45 to determine which imaging wavelength was the most robust for RPE cell imaging. Th is method calculates the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the Fourier domain by differentiating the signal and noise from the radially averaged power spectrum of the 2D Fourier transform. Figure 5a) shows the SNR values across wavelength for the 3 age groups along with the average of all age groups. It was clear that the excitation wavelength that produced images with the highest SNR values was 720 nm, illustrated with a distinct peak at 720 nm for all age groups. Based on the average SNR values of all age groups, the excitation wavelength that produced the highest quality images was 720 nm with 65.0 dB and the worst was 660 nm with 45.0 dB. The SNR value at 720 nm is highest with the young age cohort at 73.9 dB and lowest with the old age cohort at 58.3 dB. There was a gradual decrease in SNR in both directions from the 720 nm peak. Figure 5b) shows the range of SNR values across all age groups when accounting for all imaging wavelengths. The mean SNR value for the young age cohort (56.2 dB) was higher than that of the middle (52.4 dB) and old (47.9 dB) age cohorts. Figure 5c) shows the SNR values across the 3 age groups for images produced with 720 nm only. This comparison was done to compare the image quality across the age groups with the imaging wavelength that produced the highest image quality. The mean SNR value for the young age cohort (73.9 dB) was higher than the middle (63.1 dB) and old (58.3 dB) age cohorts. The middle age cohort had more variance in SNR values with a standard deviation of 14.3 dB compared to the young and old age cohorts with standard deviations of 6.6 and 12.5 dB respectively.

Visual representation of the differences in image quality, quantified with SNR, across wavelength. (a) Shows the SNR values for the individual age groups across wavelength (18–39: blue; 40–59: orange; 60+: green) and their average (red). The SNR values of the high contrast average images were plotted for all age groups. (b) shows the distribution of the SNR values across the three age groups over all wavelengths and (c) shows the distribution exclusively 720 nm.

Spatial AF variance across age and wavelength

The AF variance was compared across age groups and eccentricity. Examples of RPE cells with varying AF variance can be seen in Fig. 6 from the 3 age groups. The RPE cells from the fovea of a 20 y.o. female (young age group) can be seen in Fig. 6a). A group of cells with low AF variance are indicated with a red box. When looking at the zoomed view of these cells, the pattern of AF signal for the RPE cells appeared consistent across wavelength. The AF signal from the RPE at the different wavelengths had similar patterns of fluorescence and the centers of the RPE cells had a distinct lack of signal. However, when looking at the cells with high AF variance (indicated in the cyan box), the spatial AF pattern was more variable across wavelength. The longer wavelengths did not show a well-defined cell border but became more defined when approaching the shorter wavelengths. Examples of RPE cells with high AF variance for a 53 y.o. male (middle age group) at \(11^{\circ }\) temporal and a 64 y.o. female (old age group) at \(11^{\circ }\) temporal can be seen in Fig. 6b) and 6c) respectively. The cells appeared to have varying appearances when looking at them across the different wavelengths, further emphasizing the differences seen in the spatial pattern of AF across spectrum.

AF variance across the 3 age groups. Each age group shows the high contrast average image of the RPE cells on the left and the AF variance heatmap on the right. (a) shows the RPE from a 20 y.o. female at the fovea. The cyan box represents a group of cells that show relatively high AF variance within the image whereas the red box shows a group of cells with relatively low AF variance. A zoomed-in-view of those cells can be seen within the rectangle with its corresponding color. (b) Shows the RPE from a 53 y.o. male at \(11^{\circ }\) temporal and (c) shows the RPE from a 64 y.o. female also at \(11^{\circ }\) temporal. The scale bars represent 50 \(\mu\)m.

The overall AF variance of the RPE from the three age groups can be seen in Fig. 7. Figure 7a) shows the probability density function of the AF variance for the three age groups. The range of AF variance values (arbitrary units ranging between 0 and 1) between the 1st and 3rd quartiles for the 3 age groups are as follows: 0.22 - 0.38 for the young age cohort, 0.26 - 0.46 for the middle age cohort, and 0.29 - 0.48 for the old age cohort. The median AF variance for the young age cohort lies on 0.30 whereas the middle and old age cohort lie on 0.34 and 0.37 respectively. Figure 7b) illustrates the differences in AF variance across eccentricity and age groups. Across all eccentricities, the median of the young age cohort is below both the middle and old age cohort. This depicts a clear trend showing that AF variance is lower in the young age cohort compared to the middle and old age cohorts. The median of the middle age cohort has a higher AF variance value than the old age cohort at 4 retinal locations (5 - \(8^{\circ }\) temporal), but at the other 9 retinal locations, the old age cohort has a higher median AF variance value. Figure 7c) plots the AF variance across the ages of the individual participants. The color scheme for each participant corresponds to the age groups they belong in. The best-fit-line has an r value of 0.668, indicating a moderate positive correlation between age and AF variance.

a) The peaks of the histogram moves towards higher AF variance values with age. The magenta bar at AF variance value of 1 represents all the outliers from the three age groups. b) AF variance plotted for all age groups at each eccentricity. The 40–59 and 60+ age groups have higher AF variance than the 18–39 age group at all eccentricities. c) Average AF variance for all participants plotted against age. The R value of the best fit line is 0.668, representing a moderately strong positive correlation between age and AF variance.

Discussion

Though RPE cells have been successfully imaged previously with AOSLO, a routine setup for AOSLO AF imaging of the RPE has been elusive. This is due to challenges such as potential safety hazards, patient comfort, and required chromatic aberration compensation for SWAF and low signal and SNR for NIRAF. A previous study imaged the RPE cells with 532 nm and 796 nm light33. Comparisons between 532 and 796 nm images were done qualitatively but they did not delve deep into the implications of this. Furthermore, there are no previous studies that have evaluated the image quality of the RPE cells while utilizing more than two excitation wavelengths in the same eyes. Here, we showed that the high contrast average AF images produced the highest SNR images of the RPE cells. However, for routine imaging, this method is impractical due to the long duration of imaging across multiple imaging sessions. To acquire this dataset, a participant would need to be imaged on the AOSLO system with 8 different imaging wavelengths across 4 imaging sessions. This is simply impractical for routine imaging of the RPE cells. It is possible that an improved excitation and detection configuration for multi-spectral AF imaging could be implemented to overcome this limitation. For single wavelength imaging, we recommend utilizing 720 nm light for routine imaging of individual RPE cells as it produced the highest SNR images compared to the other individual wavelengths. The configuration for 720 nm excitation had the broadest emission detection along with the highest light power level. Although melanin is more efficient with shorter wavelengths20, the combination of higher light levels and broader emission was more important for increasing SNR than the fluorophore efficiency. For the purposes of analyzing the spatial AF variability across wavelength at the cellular level, a new method for segmenting RPE cells in AOSLO image was developed. By utilizing Cellpose and re-training the pre-existing model (cyto2), we showed that the RPE cell segmentation was not only precise, but also robust. This study also showed that the spatial pattern of AF varies with age and that the variance of AF across wavelength increases with age. This can potentially serve as a biomarker for aging RPE.

We expected the older eyes to have lower AF variances than the younger eyes based on the findings from Taubtiz. Younger eyes were thought to have more distinct organelle excitation and emission whereas the older eyes showed colocalization of SWAF and NIRAF for the lipofuscin orgranelles24. However, our results showed the opposite where AF variance increased with age. We hypothesize that there may be other sources of variance present that may swamp out the effects from fluorophore spectral changes. It was assumed that the spatial AF pattern variance is caused by the spatial distribution of the fluorophores within the RPE. However, there are sources of variance that may affect the spatial AF pattern such as laser power, detected emission bandwidth, and the spectral separation between excitation and emission. These are factors that are not age dependent and may affect all age groups in this study. The laser power was not held constant across excitation wavelengths due to the ANSI standard for human imaging placing stricter constraints when imaging with light shorter than 700 nm. This may cause more excitation for certain wavelengths due to higher light powers being used. Another source of variability could be that the detected emission bandwidth and spectral separation between excitation and emission were variable across different imaging wavelengths. This was due to the constraints from off-the-shelf optical components. Custom optical components could have been used to maintain consistency for these factors, but the practical constraint of cost prevented us from doing so.

The morphological changes of the RPE in older eyes may be a potential source of AF variance. Generally, older participants have larger RPE cells than younger participants due to normal loss of RPE cells with age46. Additionally, multinucleation occurs in the RPE when a healthy cell has to adapt to its changing environment due to normal aging47. Cell enlargement and multinucleation of the RPE cells are two mechanisms in which the RPE tends to repair itself during aging46,47,48. Under normal conditions, melanin containing organelles reside around the cell nuclei and within the apical processes of the RPE cell whereas lipofuscin organelles tend to reside on the edges of the RPE cell49. This is shown in AF imaging as a bright cell border and dark cell center, which represents the cell nucleus. Cell enlargement or multinucleation can cause irregular patterns in the AF signal. The cytoskeleton is responsible for the organization of the organelles and orgranlles within a RPE cell. If it is compromised due to morphological changes to the RPE cell, then there may be some shift of the spatial distribution of the fluorophores from the norm. This may cause more heterogeneity in the AF signal across wavelength, indicated with higher AF variance.

Another source of variance could be fluorophore organelle motion. It took four imaging sessions over the course of several days to collect one dataset for a single individual. The fluorophores in the RPE are not stagnant, but rather dynamic and mobile50. The location of a fluorophore organelle may not necessarily be consistent across imaging sessions. For instance, a lipofuscin organelle may have been imaged with short wavelength for one imaging session, visualized as a hyperfluorescent spot on the image. However for the next imaging session where the participant was imaged with NIR light, a melanin-containing organelle may have taken the place of the lipofuscin organelle from the dynamic movement of the fluorophores. The melanin-containing organelle will be visualized in the same position as the lipofuscin organelle during the previous imaging session. When analyzing the data, the assumption would be that the organelle was emitting AF signal in both the NIR and SW spectra but in reality, it was two individual organelles. The same phenomenon can also occur in depth where a lipofuscin and melanin organelle are positioned on top of one another and thus showing colocalization of AF signal in the NIR and SW spectra. This colocalization can lead to misinterpretation of the data as the source of AF colocalization is not due to the spectral changes of the RPE but rather from visualization of melanin and lipofuscin at the same position. It is difficult to detect overlapping fluorophores axially due to relatively poor axial resolution of AOSLO51,52.

Cone photoreceptors are not intrinsically autofluorescent but there are signatures of these photoreceptors in some of the AF images acquired34. These cone signatures reside mainly near the fovea and are more pronounced in the longer wavelengths. This may be due to the waveguiding properties of the cones. Photoreceptors behave as waveguides that funnel light towards the outer segments. The retina can be thought of as a matrix of optical fibers with each photoreceptor acting as a fiber optic element. The effect of the photoreceptor waveguiding on the image formation of the AF images can be theorized with multiple explanations. Light not absorbed by the photopigment that has been waveguided by the cone may cause more AF excitation near the tip of the outer segment, causing a bright spot in the image formation. Alternatively, the incoming light excites the RPE uniformly, but the photoreceptor waveguides the emitted AF light from the RPE, shown as a punctate hyper-AF spot. Lastly, the waveguiding principle of the photoreceptors can be applied both to the incoming and outgoing light. The mechanism is unknown and more work is necessary to fully understand this phenomenon.

Conclusion

This study is the first to investigate the multi-spectral AF properties of individual RPE cells in the living human eye as a function of age and eccentricity. We successfully imaged individual RPE cells from 16 participants with 8 unique wavelength bands. When considering imaging wavelength used to balance the competing interest of patient safety and comfort with efficiency and ease of implementation, the use of an imaging wavelength between 700 nm and 760 nm is advised. The specific details regarding the configuration of the signal detection for these imaging wavelengths can be seen in Table 1. These wavelengths have better robustness and image quality compared to the other configurations. The use of a broader emission bandwidth in future study could further improve the SNR for routine AF imaging at these excitation wavelengths. The multi-spectral AF data showed a moderate positive correlation between age and AF variance, suggesting that AF variance could be a potential biomarker for aging RPE. These results confirm the usage of AOSLO as a method for quantitative analysis of RPE cell morphometry and AF variability. It is known that there are changes in the AF of the retina in patients with AMD but granular AF changes are undetected by FAF due to lack of spatial resolution7. Future work will be done to identify potential biomarkers involving the AF properties of the RPE cells for early detection of AMD.

Data Availibility

The images generated for the current study and used for analysis are available at this Figshare repository.

Change history

21 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89323-3

References

Boulton, M. & Dayhaw-Barker, P. The role of the retinal pigment epithelium: Topographical variation and ageing changes. Eye 15, 384–389. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2001.141 (2001).

Bonilha, V. L. Age and disease-related structural changes in the retinal pigment epithelium. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.) 2, 413–424 (2008).

Sparrow, R. J., Hicks, D. & P. Hamel, C. The retinal pigment epithelium in health and disease. Current Molecular Medicine 10, 802–823. https://doi.org/10.2174/156652410793937813 (2010).

Yang, S., Zhou, J. & Li, D. Functions and diseases of the retinal pigment epithelium. Frontiers in Pharmacology 12, 727870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.727870 (2021).

Ambati, J. & Fowler, B. J. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. Neuron 75, 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.018 (2012).

Al-Zamil, W. M. & Yassin, S. A. Recent developments in age-related macular degeneration: a review. Clinical Interventions in Aging 12, 1313–1330. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S143508 (2017).

Ly, A., Nivison-Smith, L., Assaad, N. & Kalloniatis, M. Fundus autofluorescence in age-related macular degeneration. Optometry and Vision Science 94, 14 (2017).

Fleckenstein, M. et al. Age-related macular degeneration. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 7, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00265-2 (2021).

Si, Z., Zheng, Y. & Zhao, J. The role of retinal pigment epithelial cells in age-related macular degeneration: Phagocytosis and autophagy. Biomolecules 13, 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13060901 (2023).

Hartong, D. T., Berson, E. L. & Dryja, T. P. Retinitis pigmentosa. The Lancet 368, 1795–1809. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69740-7 (2006).

Sakai, D. et al. Retinal pigment epithelium melanin imaging using polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography for patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Scientific Reports 12, 7115, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11192-x (2022). Publisher: Nature Publishing Group.

Burke, T. R. et al. Quantitative fundus autofluorescence in recessive stargardt disease. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 55, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-13624 (2014).

Jauregui, R. et al. Retinal pigment epithelium atrophy in recessive stargardt disease as measured by short-wavelength and near-infrared autofluorescence. Translational Vision Science & Technology 10, 3. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.10.1.3 (2021).

Thomas, D. & Duguid, G. Optical coherence tomography-a review of the principles and contemporary uses in retinal investigation. Eye 18, 561–570, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700729 (2004). Publisher: Nature Publishing Group.

Eladawi, N. et al. Optical coherence tomography: A review. In Diabetes and Fundus OCT, 191–221, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817440-1.00007-3 (Elsevier, 2020).

Solbach, U., Keilhauer, C., Knabben, H. & Wolf, S. Imaging of retinal autofluorescence in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Retina 17, 385–389. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006982-199709000-00005 (1997).

Delori, F. C., Fleckner, M. R., Goger, D. G., Weiter, J. J. & Dorey, C. K. Autofluorescence distribution associated with drusen in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 41, 9 (2000).

Yung, M., Klufas, M. A. & Sarraf, D. Clinical applications of fundus autofluorescence in retinal disease. International Journal of Retina and Vitreous 2, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40942-016-0035-x (2016).

Schmitz-Valckenberg, S., Holz, F. G., Bird, A. C. & Spaide, R. F. Fundus autofluorescence imaging: review and perspectives. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.) 28, 385–409, https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0b013e318164a907 (2008).

Keilhauer, C. N. & Delori, F. C. Near-infrared autofluorescence imaging of the fundus: Visualization of ocular melanin. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 3556. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.06-0122 (2006).

Delori, F. C. et al. In vivo fluorescence of the ocular fundus exhibits retinal pigment epithelium lipofuscin characteristics. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 36, 718–729 (1995).

Kellner, U. et al. Lipofuscin- and melanin-related fundus autofluorescence visualize different retinal pigment epithelial alterations in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Eye 23, 1349–1359, https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2008.280 (2009). Publisher: Nature Publishing Group.

Sparrow, J. R. & Duncker, T. Fundus autofluorescence and RPE lipofuscin in age-related macular degeneration. Journal of Clinical Medicine 3, 1302–1321, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm3041302 (2014). Number: 4 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

Taubitz, T., Fang, Y., Biesemeier, A., Julien-Schraermeyer, S. & Schraermeyer, U. Age, lipofuscin and melanin oxidation affect fundus near-infrared autofluorescence. EBioMedicine 48, 592–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.09.048 (2019).

Duncker, T. et al. Correlations among near-infrared and short-wavelength autofluorescence and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in recessive stargardt disease. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 55, 8134. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-14848 (2014).

Roorda, A. et al. Adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Optics Express 10, 405. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.10.000405 (2002).

Roorda, A., Zhang, Y. & Duncan, J. L. High-resolution in vivo imaging of the RPE mosaic in eyes with retinal disease. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 2297. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.06-1450 (2007).

Morgan, J. I. W., Dubra, A., Wolfe, R., Merigan, W. H. & Williams, D. R. In vivo autofluorescence imaging of the human and macaque retinal pigment epithelial cell mosaic. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 1350. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.08-2618 (2009).

Scoles, D., Sulai, Y. N. & Dubra, A. In vivo dark-field imaging of the retinal pigment epithelium cell mosaic. Biomed. Opt. Express 4, 1710. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.4.001710 (2013).

Tam, J., Liu, J., Dubra, A. & Fariss, R. In vivo imaging of the human retinal pigment epithelial mosaic using adaptive optics enhanced indocyanine green ophthalmoscopy. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 57, 4376–4384. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-19503 (2016).

Gray, D. C. et al. In vivo fluorescence imaging of primate retinal ganglion cells and retinal pigment epithelial cells. Optics Express 14, 7144. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.14.007144 (2006).

Liu, T., Jung, H., Liu, J., Droettboom, M. & Tam, J. Noninvasive near infrared autofluorescence imaging of retinal pigment epithelial cells in the human retina using adaptive optics. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 4348. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.8.004348 (2017).

Granger, C. E. et al. Human retinal pigment epithelium: In vivo cell morphometry, multispectral autofluorescence, and relationship to cone mosaic. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 5705. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.18-24677 (2018).

Grieve, K. et al. In vivo near-infrared autofluorescence imaging of retinal pigment epithelial cells with 757 nm excitation. Biomed. Opt. Express 9, 5946. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.9.005946 (2018).

Vienola, K. V. et al. Microstructure of the retinal pigment epithelium near-infrared autofluorescence in healthy young eyes and in patients with AMD. Scientific Reports 10, 9561. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66581-x (2020).

Vinas, M., Dorronsoro, C., Cortes, D., Pascual, D. & Marcos, S. Longitudinal chromatic aberration of the human eye in the visible and near infrared from wavefront sensing, double-pass and psychophysics. Biomed. Opt. Express 6, 948. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.6.000948 (2015).

LIA. ANSI Z136.1-2014 for Safe Use of Lasers (Laser Institute of America, 2014).

Vienola, K. V., Holmes, J. A., Glasso, Z. & Rossi, E. A. Head stabilization apparatus for high-resolution ophthalmic imaging. Applied Optics 63, 940–944. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.513801 (2024).

Rui, Y. et al. Label-free imaging of inflammation at the level of single cells in the living human eye. Ophthalmology Science 0, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xops.2024.100475 (2024).

Nelder, J. A. & Mead, R. A simplex method for function minimization. The Computer Journal 7, 308–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/comjnl/7.4.308 (1965).

Zhang, M. et al. Strip-based digital image registration for distortion minimization and robust eye motion measurement from scanned ophthalmic imaging systems. Biomed. Opt. Express 12, 2353. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.418070 (2021).

Chen, M. et al. Multi-modal automatic montaging of adaptive optics retinal images. Biomed Opt Express 7, 4899–4918. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.7.004899 (2016).

Guizar-Sicairos, M., Thurman, S. T. & Fienup, J. R. Efficient subpixel image registration algorithms. Optics Letters 33, 156. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.33.000156 (2008).

Stringer, C., Wang, T., Michaelos, M. & Pachitariu, M. Cellpose: a generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation. Nature Methods 18, 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01018-x (2021).

Brennan, B. D., Heitkotter, H., Carroll, J., Tarima, S. & Cooper, R. F. Quantifying image quality in AOSLO images of photoreceptors. Biomedical Optics Express 15, 2849–2862, https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.516477 (2024). Publisher: Optica Publishing Group.

von der Emde, L. et al. Histologic cell shape descriptors for the retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration: A comparison to unaffected eyes. Translational Vision Science & Technology 11, 19. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.11.8.19 (2022).

Chen, M. et al. Retinal pigment epithelial cell multinucleation in the aging eye - a mechanism to repair damage and maintain homoeostasis. Aging Cell 15, 436–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12447 (2016).

Gao, H. & Hollyfield, J. G. Aging of the human retina. differential loss of neurons and retinal pigment epithelial cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 33, 1–17 (1992).

Bermond, K. et al. Autofluorescent granules of the human retinal pigment epithelium: Phenotypes, intracellular distribution, and age-related topography. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 61, 35. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.61.5.35 (2020).

Liu, Z., Kurokawa, K., Hammer, D. X. & Miller, D. T. In vivo measurement of organelle motility in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biomedical Optics Express 10, 4142–4158. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.10.004142 (2019).

Romero-Borja, F., Venkateswaran, K., Roorda, A. & Hebert, T. Optical slicing of human retinal tissue in vivo with the adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Appl. Opt. 44, 4032–4040. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.44.004032 (2005).

Zhang, Y., Poonja, S. & Roorda, A. Mems-based adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Opt. Lett. 31, 1268–1270. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.31.001268 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH Grant R01EY030517, National Eye Institute Core Grant for Vision Research P30 (EY08098), the NVIDIA Academic Hardware Grant Program, and The Eye and Ear Foundation of Pittsburgh, and Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, N.Y. USA. The authors would like to thank Austin Roorda for sharing his AOSLO software and Pavan Tiruveedhula for electronics fabrication and software guidance/support. The author would also like to thank Jennifer Hunter and Janet Tang for guidance related to light safety for imaging the living human eye.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.W.L. and E.A.R. conceived the experimental setup, D.M.W.L. collected and processed the data, D.M.W.L. and E.A.R. analyzed the data and interpreted the comparisons, M.Z. developed custom software to register data, V.C.S. recruited participants and assisted with the imaging. D.M.W.L. wrote the manuscript, E.A.R. provided revisions for the manuscript, and all co-authors reviewed the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A portion of this work include technologies that E.A.R. is an inventor of for patents that are owned by the University of Rochester (US Patent No.: US 10,123,697 and US 10,092,181). No other authors have any competing interests to disclose related to this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgements section in the original version of this Article was incomplete. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction published with this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, D.M.W., Zhang, M., Snyder, V.C. et al. Multi-spectral autofluorescence variability of the individual retinal pigmented epithelial cells in healthy aging eyes. Sci Rep 14, 30012 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81433-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81433-8