Abstract

In this work, Density Functional Theory (DFT) on Gaussian 09 W software was utilized to investigate the phenylephrine (PE) molecule (C9H13NO2). Firstly, the optimized structure of the PE molecule was obtained using B3LYP/6-311 + G (d, p) and CAM-B3LYP/6-311 + G (d, p) basis sets. The electron charge density is shown in Mulliken atomic charge as a bar chart and also as a color-filled map in Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP). Using these properties, the possibility of different charge transfers occurring within the molecule was evaluated. The calculated values of the energy gap from HOMO-LUMO mapping, illustrated in Frontier Molecular Orbitals (FMO) and Density of State (DOS), were found to be similar for both the neutral and anion states in the gaseous and water solvent phases. Both the global and local reactivity were studied to understand the reactivity of the PE molecule. Using the thermodynamic parameters, the thermochemical property of the title molecule was understood. Non-covalent interaction was studied to understand the Van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, and steric repulsion in the title molecule. Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Analysis was performed to understand the strongest stabilization interaction. In the vibrational analysis, Total Electron Density (TED) assignments were done in the intense region where the frequency of the title molecule was shifted distinctly. For vibrational spectroscopy, FT-IR and Raman spectra in the neutral and anion states were plotted and compared. Using the TD-DFT technique, the UV-Vis spectra along with Tauc’s plot were studied. Finally, topological analysis, electron localized function (ELF), and localized orbital locator (LOL) were performed in the PE molecule.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

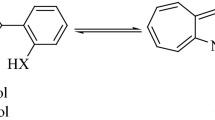

Phenylephrine (PE), also known as (R)-3-[-1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino) ethyl]phenol, is an aromatic benzene ring organic compound with side chain hydroxyl-ethylamino. The crystal structure of the PE molecule is monoclinic and is found to exist in zwitterions in the crystals1. PE is used for temporary relief of the nasal stuffiness caused by fever, allergies, or colds2,3. The primary uses of PE as a drug are as a decongestant to treat hemorrhoids, raise blood pressure, and dilate pupils. When it comes to preventing and treating hypotension during spinal anesthesia for cesarean sections, it is the first option4,5. Being a pure α-agonist, PE also increases the cardiac output by raising the cardiac preload6. As a sympathomimetic amine medication, PE has bioavailability due to its prolonged first-pass metabolism7. Moreover, phenylephrine is applied as an eyedrop to enlarge the pupil and make the retina easier to see8. In 1976, PE was approved by the FDA as well and is safe and effective to use under the prescription of experts.

Even though PE is used orally as a nasal decongestant, many articles provide conflicting views on its effectiveness. The article by R Eccles et al. doubts the effectiveness of PE since it was mainly introduced to replace pseudoephedrine (PDE) as a means of controlling the production of methamphetamine9. This has caused people to switch from PDE to PE in many common cold and cough medicines. The article by L. Hendeles et al. concurs with the previous argument, saying that at the FDA-approved dose of 10 mg for adults, it is unlikely to provide relief of nasal congestion. Because of its substantial first-pass metabolism in the liver and stomach, it has a low oral bioavailability10. However, the article by Desjardins et al. takes the side of the FDA, saying that the totality of scientific evidence supports the nasal decongestant efficacy of PE11. On September 11, 2023, the FDA concluded that current scientific data do not support the recommendation that the recommended dose of orally administered phenylephrine is effective as a nasal decongestant. But the FDA still has no clear recommendation on nasal sprays containing PE to treat congestion12.

Theoretical calculations based on the DFT of PE have been done before under different settings; mostly PE is studied together with hydrochloride since it improves stability and solubility, and this combined agent acts similar to epinephrine and ephedrine13. In the article Wab et al., the researcher explored thermal, thermodynamic, and kinetic studies of PE hydrochloride in nitrogen and oxygen14.

Being a stable compound with its multiple applications, there has been an extensive study of phenylephrine hydrochloride, but not many articles can be found that study the physical properties of PE alone. This lack of study inspired us to study the PE molecule. In this work, we used the DFT approach with the B3LYP/6-311 + G (d, p) and CAM-B3LYP/6-311 + G (d, p) basis sets to generate the optimized PE molecule. Here, we studied physical properties like MEP, FMO, global reactivity descriptors, local reactivity descriptors, DOS, Mulliken atomic charge, thermochemistry, NCI, TED, performed spectroscopical analysis like FT-IR, Raman, UV-Vis, and finally studied ELF and LOL for topological analysis. We have compared the results of most of these properties in their neutral and anion states. We have even compared some of the properties in different phases, like the gaseous phase and the water solvent phase. To the best of our knowledge, the spectroscopic, quantum chemical, and topological calculations of the PE molecule have not been studied for the gaseous and anion states together.

Methods of computation

In this study, the computation of the PE was performed by the method of DFT using the popular model Becke-3-Lee–Yang–Parr (B3LYP) with a 6-311 + G (d, p) basis set in the Gaussian 09 W program15. The optimized structure was used to calculate HOMO-LUMO and MEP using the Gauss View 6.0.1616. The DOS in neutral and anion states was performed using Gauss Sum 3.0 program17. The FT-IR and Raman spectra were calculated using a scaling parameter factor of 0.966. The vibrational assignment was obtained using VEDA 4 software18. Finally, using Multiwfn software 3.8 package to perform topological analysis (ELF and LOL) was carried out19.

From Koopman’s theorem, certain chemical descriptors are defined, like electronic chemical potential (μ), chemical hardness (η), global softness (S), and global electrophilicity index (ω)20.

An electron or a group of electrons having the tendency to escape from a molecule is measured by their electronic chemical potential, which may be computed using the HOMO–LUMO as,

The resistance of an atom to transfer the charge is measured by its chemical hardness (η) and can be calculated as,

The ability of an atom or set of atoms to accept electrons is referred to as global softness (S), which is reciprocal of chemical hardness and can be measured as,

Electrophilicity is the ability to acquire additional electronic charge and the system’s resistance to exchange electronic charge for its surroundings. Hence, the global electrophilicity index (ω) can be calculated as,

Translational, vibrational, and rotational motion contributions can be used to characterize the thermodynamic function of total internal energy (U).

Here Utrans = translational motion’s contribution to total internal energy.

Uvib = vibrational motion’s contribution to total internal energy.

Urot = rotational motion’s contribution to total internal energy.

Uelec = Electronic motion’s contribution total internal energy.

In theory, electronic motion provides the entropy given by,

The electronic partition function is represented by R, which stands for the ideal constant and \(\:qe\).

The concept of the condensed Fukui function divides into three functions as,

One is related to reactivity toward nucleophile attack (\(\:{f}^{+}\)), and it is given by:

Another is related to reactivity toward electrophilic attack (\(\:{f}^{-})\), and it is given by:

Here, \(\:\rho\:\) represents the electron density and N represents the number of electrons, So, \(\:{\rho\:}_{N+1}\left(r\right)\) density of the anion generated by adding one electron to \(\:{\rho\:}_{N}\left(r\right)\), and \(\:{\rho\:}_{N-1}\left(r\right)\:\)density of the cation created from removing one electron to \(\:{\rho\:}_{N}\left(r\right)\).

Result and discussion

Geometrical parameters

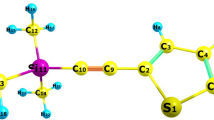

The optimized structure of the PE molecule is obtained by Gaussian 09 W software with the B3LYP method and 6311 + G (d, p) basis set. The optimized molecule is shown in Fig. 1, with a label and symbol using Gauss View 6.0.16. The bond length, bond angles, and dihedral angles are summarized in Table 1 for the neutral and anion states in the gaseous phase.

The geometrically optimized molecule shows the bond length between two corresponding molecules, bond angle, and dihedral angle (between two planes), which are shown in Table 1. We.

observed a slight change in bond length and bond angle for different combinations of atoms, apart from the case of the benzene ring, where the distance between C-C is 1.39 Å and C-H is 1.08 Å. The highest dihedral angle is 179.010 between atoms H25-O2-C9-C7 and − 174.640 between C5-N3-C12-H24 in neutral and anion states, respectively. Since introducing more electrons influences the density of electrons, which alters the bond length and bond angles, an increase in bond length between most of the atoms signifies a high electron density in the anion state as compared to the neutral state.

From Table 2, we are able to make observation that the total energy of the PE molecule is continually increasing from the neutral to the anion state, and the energy is even higher in the solvent water than in the gaseous phase. This signifies that the PE molecule shows more stability in the presence of solvent water than in the gaseous state, and the anion state shows more stability in comparison to the neutral state.

The comparison of minimum energy and dipole moment for the neutral and anion states in the gas phase and water solvent phase were obtained using the B3LYP and CAM-B3LYP models, respectively, and are tabulated in Table 2. The model CAM-B3LYP shows more stabilization energy and dipole moment values than the B3LYP model. The value of dipole moment has been increasing continuously with gas phase to water solvent phase; the higher value dipole moment enhances the polarity of the molecule. The value of the dipole moment in anion states shows more polar nature than neutral states. The addition of water as a solvent to the neutral state shows a decrease in convergence energy and an increase in dipole moment, respectively. In the anion state in the water solvent phase, the dipole moment is 8.18 Debye, indicating a high polarity due to the polar nature of water.

Molecular electrostatic potential

The molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) is a useful tool for evaluating physical and chemical parameters for biomolecules and organic compounds. It is also usually used to study the intermolecular characterization and actions for the drug analysis of molecules21,22. The 3D plots of MEP for the title molecule are illustrated in Fig. 2 (a and b). This plot is mapped onto the electron density surface. The MEP helps us study the reactive site for the nucleophilic or electrophilic site of the compound23,24. The molecular systems’s MEP map shows a densely.

MEP maps for title molecule (a) in the neutral state and (b) in the anion state were obtained by using model B3LYP with basis set 6-311 + G (d, p) in Gaussian09 software. The different color gradient represents the electrostatic potential; the red color region indicates negative potential, and the blue color represents positive potential.

The surface region for both neutral and anion states is presented in the following sequence: red < orange < yellow < green < blue. In the neutral state, the electron density value ranges from − 5.555e-2 to 5.555e-2. Similarly, in the anion state, the electron density value ranges from − 0.167 to 0.167. The neutral state mainly comprises electrophilic regions, with the region near the H25 molecule exhibiting a more electrophilic nature than the region near C6, C7 and C8, while in the anion state, the nucleophilic region is predominant, with the regions like O1, C6, and C7 showing a more nucleophilic nature than C12 and H25 near the (O1 and O2) molecule, which corresponds to the electrophilic region25.

Mulliken atomic charges

The Mulliken atomic charge visualizes the distribution of electron density among atoms in a compound26. Electronic structure, dipole moment, polarizability, and other molecular properties are all directly impacted by the atomic charge27,28.

In Fig. 3, the Mulliken atomic charge of atom C6 has the greatest positive value in both neutral and anion states. The C6 and C7 have the highest positive charge in both neutral and anion states. These atoms act like an electrophilic site, having less electron density. Similarly, C4 and C8 have the highest negative charge in both neutral and anion states. Also, C9 and C10 have the greatest negative charges, which shows the nucleophilic site representing the highest electron density. The highest negative charge has been observed in atoms C4 and C8 in both neutral and anion states, acting like a neucleophilic site for electrophilic attack.

Frontier molecular orbitals

Frontier molecular orbitals (FMO) are the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), which are located at the outermost boundaries of the system. The HOMO represents the ability to donate an electron, also called a nucleophile. LUMO represents the ability to gain an electron, also known as an electrophile29,30. The energy gap of the molecule refers to the difference between LUMO and HOMO31.

Ground state (HOMO) Ground state (HOMO).

The calculated HOMO-LUMO and the energy gap of the PE molecule in (a) the gaseous phase and (b) the water solvent phase using the CAM-B3LYP model with a scaling parameter of 0.961 in the basis set 6-311 + G (d, p). In the neutral state with the water solvent phase, the energy gap between HOMO and LUMO is greater, indicating more stability and less reactivity.

The energy gap (ΔE) is measured in eV or kcal/mol. The pictorial representation of the title molecule’s Frontier molecular orbitals is calculated in the gas phase and using water solvent with the 6-311 + G (d, p) basis set, as shown in Fig. 4 (a and b) and tabulated in Table 3. The negative and positive phases are denoted by the colors red and green, respectively.

In the neutral state, where there is no spin polarization, both spin up and spin down yield the same result. That is, both alpha and beta of HOMO and LUMO have the same value, respectively. From Fig. 4(a) and Table 3, the energy difference between LUMO and HOMO is 8.01 eV for the neutral state in the gaseous phase. Similarly, from Fig. 4(b) and Table 3, the energy difference between LUMO and HOMO is 8.34 eV for the neutral state in the water solvent. The energy gap between HOMO and LUMO in neutral anion state with water solvent is greater than neutral state in gas phase, which shows anion water solvent is more stable, which means lowest chemical reactivity and highest kinetic stability.

HOMO-LUMO and energy gap of the PE molecule in anion state (alpha and beta) in (a) the gaseous phase and (b) solvent water phase are obtained using the CAM-B3LYP model in the basis set 6-311 + G (d, p). The energy gap between HOMO and LUMO in the anion state in the water solvent phase has more than an anion phase.

In the anion state, spin polarization comes into play, so we can observe the existence of both alpha HOMO and beta HOMO, and alpha LUMO and beta LUMO with their respective values, unlike in the neutral state, which had single values for both. The respective values of alpha LUMO, alpha HOMO, beta LUMO, and beta HOMO and their differences, which yield energy gaps, are presented in Fig. 5 (a and b) and Table 3. For the anion state in both the gaseous phase and in the water solvent. The title molecule shows a higher energy gap in the anion state in the water solvent than the anion sate in the gas phase.

Density of States

The optimized structure of the PE molecule is re-optimized using basis set 6-311 + G (d, p) with model CAM-B3LYP. The Gauss Sum 3.0 program was used to calculate the density of states (DOS) spectrum with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 0.3 eV32. The energy level per unit energy increment is explained by the density of the state spectrum. So, higher DOS at a given energy level indicates greater availability for states to be occupied33,34.

The green lines indicate the HOMO, and the red lines indicate the LUMO energy levels. The DOS of the neutral state calculation is illustrated in Fig. 6 (a and b), whereas the DOS of the anion state is presented in Fig. 7 (a and b) within the energy range of -15 eV to 15 eV. These spectrums of the DOS illustrate the number of states with different energy levels.

The PE molecule’s density of states (DOS) shows the range of electronic states that can be occupied in the neutral state in (a) the gaseous phase and (b) the water solvent phase, from − 15 eV to 15 eV. The DOS was calculated using the CAM-B3LYP model in the basis set 6-311 + G (d, p) using Gaussian09. The gap between the valance (occupied) and conduction (virtual) states in the neutral gas phase is 8.02 eV and in the water solvent phase 8.30 eV.

The energy disparity between the virtual (acceptor) and occupied (donor) orbitals defines the energy gap between their corresponding states and phases. Form Fig. 6. For a neutral state in the gaseous phase, the energy gap was found to be 8.02 eV, and for the water solvent phase, it was observed to be 8.30 eV, which are both consistent with the difference of LUMO (alpha) and HOMO (alpha) of 8.01 eV and 8.34 eV for the gaseous and water solvent phases in the neutral state, respectively.

From Fig. 7 (a), In the DOS of the title molecule for the anion state in the gaseous phase, the energy difference between the alpha virtual orbital and the alpha occupied orbital is 2.25 eV, and the energy difference between the beta virtual orbital and the beta occupied orbital is 7.35 eV. From Fig. 7 (b), In the DOS for the anion state in the water solvent phase, the energy difference between the alpha virtual orbital and the alpha occupied orbital is 4.01 eV, and the energy difference between the beta virtual orbital and the beta occupied orbital is 7.74 eV. These calculated energy differences of anion state in both the gaseous and water solvent phases are in agreement with the energy difference calculated in FMO from the difference of LUMO and HOMO, which is presented in Fig. 5.

Reactivity descriptors

Global reactivity descriptors

For the purpose of comprehending and anticipating a system’s reactivity, global reactivity descriptors describe the electronic structure and characteristics of the system overall35. The expressions from Eqs. (1)-(4) are used to calculate different reactivity descriptors. The calculated global reactivity descriptors are tabulated in Table 4 for the cases where spin is polarized or not.

From Table 4, the electron affinity for the neutral state is negative, meaning the process is endothermic, which is energetically favorable. In contrast, the electron affinity of the anion state is positive, meaning the process is exothermic. In the solvent water phase, electron affinity is higher for both cases than its counterpart, indicating stronger attraction for electrons, resulting in greater energy release upon electron addition and a more stable anion. For ionization energy, the observation implies that water as a solvent has a significant stabilizing effect on the anion state due to its polar nature and ability to form hydrogen bonds, which lower the ionization energy in the water-solvent than in the gaseous phase for the anion state. Meanwhile, in the neutral state, the presence of the water solvent increases the ionization energy compared to the gaseous phase. For chemical hardness, the observation implies that the title molecule is more stable and less polarizable when in a gaseous state than in the presence of the water solvent for both the neutral and anion states36. From chemical potential, it can be observed that the title molecule is energetically favored or more stable in the gaseous phase than in the water solvent phase for the neutral and anion states. The anion state has more tendency to lose electrons than the neutral state, indicates that neutral is more stable than the anion state. The higher electrophilicity index in the water solvent phase compared to the gaseous phase in both the neutral and anion states suggests that the molecule becomes more reactive toward nucleophiles when dissolved in water37. This indicates that the neutral phase acts with a more electrophilic nature than the anion phase.

Local reactivity descriptor (Fukui function)

The local reactivity parameters were calculated using UCA-FUKUI 1.0 software package. The local reactivity descriptor, such as the Fukui function, reveals the preferred locations where a molecule will adjust its density when the number of electrons changes. It also reflects the inclination of the electronic density to deform at a certain point upon absorbing or donating electrons38. Using Eqs. (7)-(9), we have calculated the reactivity of the corresponding attack, which is an electrophilic, nucleophilic, and radial attack, and it is presented in Table 5. The atom that has the largest Fukui function (f) will have the highest reactivity39. The respective value for the calculated Fukui function is given in Table 5.

The calculated value of Fukui function of PE molecule with NBO charges has reactivity order for the nucleophilic attack (f+): C4 > C11 > H20 > C5 > O1 > C6 > C12 > H13. The nucleophilic attack interacts with electrophiles with electron-deficient sites. The C4 atom has the most effective value than other atoms from interaction between electrophile and nucleophile. The order of electrophilic (f−) attack is N3 > C8 > O2 > C11 > H15 > C9 > H23 > C7. The atom N3 shows the highest value of electrophilic attack-seeking nucleophlic site. Finally, for radical (f0) attack reactivity order are C4 > N3 > C11 > C8 > O2 > H20 > C9 > C7. The atom N3 also shows the highest probability for radical attack. The presence of unpaired electrons in the N3 atom, which cause highly reactive reactions and take part in complex reactions.

Thermochemistry

The statistical parameters are analyzed in relation to thermodynamic functions, including thermal energy (E), heat capacity (Cv), entropy (S), and zero-point vibrational energy, which are computed. The thermodynamic parameters are computed and presented in Table 6. The total energy comprises electronic, translational, rotational, and vibrational energy. Equation (6) indicates that the lack of a temperature-dependent element in the partition function leads to zero internal thermal energy and electronic heat capacity due to electronic motion40.

Satisfying the theory, we acknowledge that, apart from the entropy of the anion state, electronic motion contributes nothing. The incorporation of electrons does not influence translational, rotational, or electronic motions, as their contributions are equivalent. Nonetheless, a transition in the neutral and anionic states is observable in vibrational motion. Vibrational motion in a molecule refers to the oscillation of atoms about their equilibrium positions. The molecular structure and electrical configuration dictate the specific energy level of each vibration, governing the distribution of various energy levels. Therefore, this mismatch indicates that the addition of the electron has caused changes in both the energy level and the molecular structure.

In three parameters: translational, rotational, and vibrational, vibrational energy is greater than translational and rotational energy, which results in an increase in vibrational modes such as bending and stretching. In this calculation, the zero-point vibrational energy in the neutral state is higher than that in the anion state, which indicates there is more vibrational mode in the neutral than in the anion state.

Non-covalent Interaction (NCI) analysis

It is a tool to visualize and identify non-covalent interactions, such as Van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, and steric repulsion in the molecule41. It uses the Reduced Density Gradient (RDG), which is calculated using the density and its first derivative42.

In the region far from the molecule, in which the density decays to zero exponentially, the RDG will have very large positive value. In the region of covalent and non-covalent interaction, the RDG will have a very small value close to zero43.

From the RDG plot of Fig. 8 (a and b), the blue region between − 0.03 and − 0.05, which lies at N3 and H13, indicates strong intermolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonds. The green region between 0.02 and 0.01 signifies weak intermolecular interaction, that is, Van der Waals interaction with lower density. The red region above 0.01 signifies a strong steric effect, which lies in the benzene ring and around O2 and O1.

Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis

The natural bond orbital (NBO) calculations were performed using the NBO 3.1 program implemented in the Gaussian 09 package at the DFT/B3LYP/6-311 + G (d, p) method44. Here the NBO analysis employed the second-order Fock matrix to assess the donor-acceptor interaction, and the data is tabulated in Table 7. The NBO analysis yields the most accurate depiction of the natural Lewis structure since every orbital feature is selected analytically to incorporate the maximum proportion of the electron density39. The stabilization E(2) correlated with the delocalization for each donor (i) and acceptor (j) is estimated as

Where, \(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{j}}\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:{\text{E}}_{\text{i}}\) are the diagonal elements F(i, j) is the off-diagonal NBO Fock matrix element.

In addition to offering a practical foundation for researching charge transfer or conjugative interaction in molecular systems, NBO analysis is an effective technique for examining intra- and intermolecular bonding and interactions among bonds45,46.

From Table 7, the interactions of atoms in the title molecule from donor to acceptor with the order of π (C6-C7) → π∗ (C9-C11), π (C8-C10) → π∗ (C6-C7), π (C6-C7) → π∗ (C8-C10), π (C8-C10) → π∗ (C9-C11), π (C9-C11) → π∗ (C6-C7) with energy 23.85 kcal/mol, 22.39 kcal/mol, 18.07 kcal/mol, 17.67 kcal/mol, 16.33 kcal/mol respectively. These interactions have high delocalization of electrons from stabilized π bonds to neighboring anti-bonding orbitals. The lone pair interaction from LP(2) (O2) → π∗ (C9-C11) has more stabilization energy of 26.78 kcal/mol. The interactions between these carbon atoms are C6, C7, C8, C9, C10, C11 form a benzene structure that is less stable and more reactive.

The hyper conjugative interaction with lone pairs of PE molecules using NBO orbitals are σ (C11-H21) → σ∗ (C9-C11), σ (C10-H19) → σ∗ (C10-C11), σ (C10-H19) → σ∗ (C8-C10), σ (O2-C9) → σ∗ (C7-C9) having energy of 0.51 kcal/mol, 0.54 kcal/mol, 0.63 kcal/mol, 0.65 kcal/mol respectively. Also, lone pair interactions between LP(2) (O1) → (N3-C5) and (O2-C4) → (C9-C11) having same stabilization energy of 0.76 kcal/mol. These interactions are single bonded from the sigma (σ) bond to the anti-sigma bond (σ*), having less stabilization energy with a strong bond.

Vibrational analysis

The total number of potentially active observable modes in a non-linear molecule with N atoms is equal to (3 N–6) normal modes of vibration47. The PE molecule comprises 18 atoms and 69 vibrational vibrations. Comparing 24 stretching, 23 bending, 18 torsions, and 4 out-of-plane vibrations. All vibrations were analyzed, and those that most substantially affect Raman spectra are tabulated below in Table 8.

The different modes of vibration occurring between the intensive regions of 0–4000 cm− 1 were observed and analyzed in neutral and anion states with their respective TED assignments. Phenylephrine contains functional groups like alcohols, phenols, and amines; the standard range of wavenumbers for these and additional functional groups was observed and listed below48,49.

-

Region I: >3500 cm-1. At this wavenumber, a singular vibrational mode is anticipated: the O-H stretching vibration of the alcohol functional group. In our investigation, O2-H25 exhibits a stretching vibrational wavenumber of 3837 cm-1 and 3814 cm-1 with a 100% contribution in the neutral state, and 3725 cm-1 and 3819 cm-1 with 99 and 100% contribution in the anion state for the gaseous and aqueous solvent phases, respectively.

-

Region II: 3000–3500 cm-1. At this wavenumber, two vibrational modes are anticipated: the N-H stretching vibration from the amine functional group and the C-H stretching vibration from the aromatic functional group. Our investigation indicates that N3-H18 exhibits stretching vibrations at wavenumbers of 3515 cm-1 and 3505 cm-1, both with 100% contribution in the neutral state, and at 3444 cm-1 with 99% and 3502 cm-1 with 100% contribution in the anion state, in both gaseous and aqueous phases, respectively.

-

Region III: 1000–1600 cm-1: At this range of wavenumber, C-C ring stretching and C-H bending are expected for the molecule containing an aromatic ring. From our study, C8-C10 has stretching vibrations with wavenumbers ranging from 1100 to 1400 cm-1 with a percentage contribution ranging from 10 to 20%, and H16-C7-C6 has bending vibrations with wavenumbers ranging from 1200 to 1350 cm-1 with a percentage contribution ranging from 19 to 22%.

-

Region IV: < 1000 cm-1: At this range of wavenumber, the remaining torsion and out-of-plane vibration are expected. From our study, O2-C7-C11-C9 has out-of-plane vibrations that have wavenumbers around 600’s with different TED percent contributions like 30, 31, and 51. Similarly, H18-N3-C5-C4 has torsion vibrations with wavenumbers in the 700’s and TED percent contribution from 40 to 50.

Vibrational spectroscopy

FT-IR analysis

The IR spectrum is observed due to the absorption of IR radiation by a vibrating molecule. An IR spectrum can be divided into 3 sub-regions: far-IR (< 400 cm− 1), mid-IR (4000 –400 cm− 1) and near-IR (13000 –4000 cm− 1). Typically, for the analysis of biological samples, the mid-IR region is used50.

From Table 2, we have observed that the PE molecule has a permanent dipole moment, so the PE molecule must be active in the IR region, as IR couples with the dipole moment of the molecule.

Form Fig. 9, we can observe that the cluster of peaks at the range of 301 and 1642 cm− 1 in neutral state diminishes when observed in neutral state; the same thing can be observed for the peaks at the range of 2700 to 3100 cm− 1. This may be because of a change in dipole moment of the molecule as a result of ionization, which might cause the peak to decrease, increase, or disappear altogether. Ionization can also break symmetry, which can lead to splitting or broadening the absorption band.

Raman analysis

The Raman spectrum is due to the scattering of radiation by the vibrating molecule. Determining the chemical composition of material systems, such as biological systems, has been demonstrated to be a strong and adaptable application of Raman spectroscopy, which is based on the Raman effect51,52,52. The computational spectrum for Rama spectroscopy was calculated within the region of 0–4000 cm− 1 and is given in Fig. 10.

The plot from Raman spectroscopy peaks at 3838 cm− 1 for the neutral state which is mostly due to C-H stretching vibration; similarly, at the range of 3500 cm− 1 the anion state shows the highest peak. The cluster around the range of 3000 to 4000 cm− 1 and 1000 to 1800 cm− 1 in the neutral state has more intensity as compared to the anion state. Since the symmetry of the molecule was affected when the PE molecule was ionized. Such a huge change in Raman intensity is observed.

A similar nature of plot, like in FTIR can be observed in Fig. 9. Upon ionization, the intensity of multiple peaks between 2700 and 3800 cm− 1 from the neutral state diminished to a nearly negligible state when compared to the anion state.

UV-Vis absorption spectra

The ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectra of the phenylephrine molecule were obtained by using the TD-DFT method in neutral in the presence of solvent water at 6-311 + G (d, p) basis set.

Here we performed a quantitative analysis of the phenylephrine molecule, and since the maximum wavelength was found to be 240 nm in the water solvent state at the neutral phase, we can conclude that it contains highly saturated single and covalent bonds, which fall in the ultraviolet range.

Similarly, the oscillator strength was 0.037 and the excited state energies were 5.40 eV. The C-PCM model was utilized to analyze the effect of the solvent (Fig. 11).

Tauc’s relation is illustrated utilizing the optical energy gap (Eg) and absorption coefficient (α) derived from UV-Vis data53.

The optical band gap54,55 was found to be 5.79 eV of the title molecule from Tauc’s plot. It signifies that an energy of 5.79 eV can make an electronic transition in the PE molecule.

Topological analysis

The Multiwfn 3.8 program illustrates the Electron Localization Function (ELF) and Localized Orbital Locator (LOL). The color-filled projection maps of ELF and LOL, obtained from the Multiwfn program, with a range of 0–1 and 0-0.8, respectively, are plotted in Fig. 12 (a and b). The electron density and electron wave function are estimated by using techniques of electron localization (ELF) and localized orbital locator (LOL)56.

In the ELF map, from Fig. 12 (a), the delocalized electrons between non-bonded atoms are represented in the region < 0.5. The region of high electron density between bonded atoms is represented in the region > 0.5. The red color represents high electron localization, and the blue color represents high electron delocalization57,58. The delocalized electrons around carbon and nitrogen atoms (C4, C12, and N3) are represented with blue regions, whereas the high values of bonded pairs59 are represented around hydrogen atoms (H13, H14, and H18), indicating shared electron pairs. In LOL, Fig. 12 (b) shows the white region around the atoms (H13, H14, and H18), indicating regions of low electron localization60 against regions of high electron localization in red color61,62.

Conclusions

Density Functional Theory is used alongside the 6-311 + G (d, p) basis set to investigate the PE molecule, deploying the B3LYP method to optimized the title molecule using Gaussian09 software. The optimized PE molecule’s minimum total energy was found to have the same value of -15,132.85 eV and − 15132.31 eV using models B3LP and CAM-B3LYP for the anion state in the gaseous phase, respectively. The total energy decreased from − 15,133.13 eV in the neutral water solvent state to -15,134.49 eV in the anion states in model B3LYP, respectively. Similarly, using model CAM-B3LYP, the total energy has been decreased from − 15125.82 eV to -15126.94 eV. According to the MEP plot, anion states are primarily nucleophilic, while neutral states are primarily electrophilic. The Mulliken atomic distribution suggests that C6 in both the neutral and anion states shows the most electrophilic nature, C4 in the anion state, and C9 and C10 in the neutral state show the most nucleophilic nature. The HOMO-LUMO spectra and DOS of the PE molecule were calculated after re-optimizing the title molecule using the CAM-B3LYP model. The energy gap in the neutral state demonstrates a little energy difference between the gaseous and solvent water phases, unlike in the anion state, which has a noticeable variation in energy between the gaseous and solvent water states. Again, using the DOS spectrum, the energy difference was calculated between virtual and occupied orbitals, which yielded the same result as in FMO. From global reactivity, it was observed that electron affinity in the neutral state is endothermic, whereas in the anion state it is exothermic. In ionization energy, it was observed that water as a solvent has a significant stabilization effect on the anion state as compared to the gaseous phase in the anion state. The chemical hardness implies that the PE molecule has greater stability and less polarizability in the gaseous phase than in the solvent water phase; the chemical potential implies that the PE molecule has greater stability in the gaseous phase than in the water solvent phase; and the electrophilicity index implies that the PE molecule becomes more reactive towards nucleophiles when dissolved in water. Using the Fukui function, we observed the reactivity order for the electrophilic, nucleophilic, and radial attacks of the title molecule. The Fukui function shows nucleophilic attack C4 > C11 > H20 > C5 > O1 which seeks electrophilic sites C6 and C7. Similarly, the electrophilic attack N3 > C8 > O2 > C11 > H15 seeks nucleophilic sites C4, C8, C9, and C10 from Muilliken atomic charge. The prediction of electrophilic and nucleophilic sites of the title molecule from Mulliken atomic charge is more effective than MEP. According to the result of thermochemistry, there are more vibrational modes in the neutral state than in the anion state, since the zero-point vibrational energy is higher in the neutral state than in the anion state. In NCI analysis, using the RDG plot, Van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, and steric repulsion in the molecule were studied. From NBO analysis, the hyperconjugative interaction energy presented stabilization energy, which contributes to the stability of the molecule. This strong interaction between π bonding and π* anti-bonding is indicative of a stable system with well-delocalized π-electrons, commonly found in aromatic compounds like benzene. The vibrational analysis provided details on various vibration, modes and their percentage TED in different regions. RAMAN and FT-IR analyses validated the presence of several functional groups connected to this molecular organic crystal. From the UV-Vis spectra, we observed that the maximum wavelength was 240 nm, the oscillator strength was 0.37, and the excited state energy was 5.40 eV. We created Tauc’s plot using the UV-Vis spectra, revealing 5.79 eV as the optical band gap. In the topological analysis, the electron localization factor (ELF) indicated the presence of delocalized electrons near carbon and nitrogen atoms (C4, C12, and N3), high bonded pair values around hydrogen atoms (H13, H14, and H18), and low electron localization regions (H13, H14, and H18) in the PE molecule.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Andersen, A. M. The crystal and molecular structure of (–)-phenylephrine. Acta chem. Scand. 30, 193–197 (1976).

Hendeles, L. Selecting a decongestant. Pharmacotherapy: J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Therapy. 13 (6P2), 129S–134S (1993).

Hatton, R. C., Winterstein, A. G., McKelvey, R. P., Shuster, J. & Hendeles, L. Ambulatory care: efficacy and safety of oral phenylephrine: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Pharmacother. 41 (3), 381–390 (2007).

Ahmed, A. M. K., Anwar, S. M. & Hattab, A. H. Spectrophotometric determination of phenylephrine hydrochloride in pharmaceutical preparations by oxidative coupling reaction. Int. J. Drug Delivery Technol. 10, 323–327 (2020).

Magder, S. Phenylephrine and tangible bias. Anesth. Analgesia. 113 (2), 211–213 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e318220406a.

Kalmar, A. F. et al. Phenylephrine increases cardiac output by raising cardiac preload in patients with anesthesia induced hypotension. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 32, 969–976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-018-0126-3 (2018).

Trommer, H., Raith, K. & Neubert, R. H. Investigating the degradation of the sympathomimetic drug phenylephrine by electrospray ionisation-mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 52 (2), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2010.01.024 (2010).

Pandey, B. K. & Pandey, D. Parametric optimization and prediction of enhanced thermoelectric performance in co-doped CaMnO3 using response surface methodology and neural network. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 34 (21), 1589 (2023).

Eccles, R. Substitution of phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine as a nasal decongeststant. An illogical way to control methamphetamine abuse. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63 (1), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02833.x (2007).

Hendeles, L. & Hatton, R. C. Oral phenylephrine: an ineffective replacement for pseudoephedrine. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 118 (1), 279–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.002 (2006).

Desjardins, P. J. & Berlin, R. G. Efficacy of phenylephrine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64 (4), 555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02935.x (2007).

Anderson, T. S., Suda, K. J., Gellad, W. F. & Tadrous, M. Trends in Phenylephrine and Pseudoephedrine sales in the US. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.27932 (2024).

Kalasree, M. To compare the efficacy of inj. Phenylephrine hydrochloride with inj. Ephedrine hydrochloride for the treatment of Spinal Hypotension in Inguinal Hernia and Lower Limb Orthopedic Surgeries (Doctoral dissertation, Chengalpattu Medical College, Chengalpattu). (2011).

Wan, Y. et al. Thermal stability, thermodynamics and kinetic study of (R)-(–)-phenylephrine hydrochloride in nitrogen and air environments. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 148 (6), 2483–2499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-022-11911-6 (2023).

Frisch, M. J. et al. GAUSSIAN09 (Gaussian Inc., 2009).

Dennington, R., Keith, T. & Millam, J. GaussView, version 5. (2009).

O’boyle, N. M., Tenderholt, A. L. & Langner, K. M. Cclib: a library for package-independent computational chemistry algorithms. J. Comput. Chem. 29 (5), 839–845 (2008).

Jamróz, M. H. Vibrational energy distribution analysis (VEDA): scopes and limitations. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 114, 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2013.05.096 (2013).

Lu & Tian Chen. Feiwu, Multiwfn: a multifunctional analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33 (5), 580–592 (2012).

Koopmans, T. About the assignment of wave functions and eigenvalues to the individual electrons of an atom. Physica 1 (1–6), 104–113 (1934).

Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 226, 117609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2019.117609.

Singh, J. S. IR and Raman spectra with Gaussian-09 molecular analysis of some other parameters and vibrational spectra of 5-fluoro-uracil. Res. Chem. Intermed. 46 (5), 2457–2479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11164-020-04101-2 (2020).

Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 150, 543–556. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2015.05.090.

Mahalakshmi, G. & Balachandran, V. NBO, HOMO, LUMO analysis and vibrational spectra (FTIR and FT Raman) of 1-Amino 4-methylpiperazine using ab initio HF and DFT methods. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 135, 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2014.06.157 (2015).

Neto, A. F., Huda, M. N., Marques, F. C., Borges, R. S. & Neto, A. M. Thermodynamic DFT analysis of natural gas. J. Mol. Model. 23, 1–12 (2017).

Karabacak, M. et al. FT-Raman, NMR, UV–Vis spectral studies of 3-fluorophenylboronic acid. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 136, 306–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2014.08.141 (2015). DFT calculations and experimental FT-IR.

Rijal, R., Sah, M. & Lamichhane, H. P. Molecular simulation, vibrational spectroscopy and global reactivity descriptors of pseudoephedrine molecule in different phases and states. Heliyon 9 (3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14801 (2023).

Mulliken, R. S. Electronic population analysis on LCAO–MO molecular wave functions. I. J. Chem. Phys. 23 (10), 1833–1840. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1740588 (1955).

Janani, S. et al. Structural, vibrational, electronic properties, hirshfeld surface analysis topological and molecular docking studies of N-[2-(diethylamino) ethyl]-2-methoxy-5-methylsulfonylbenzamide. Heliyon 7 (10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08186 (2021).

Mamand, D. Theoretical calculations and spectroscopic analysis of Gaussian Computational Examination-NMR, FTIR, UV-Visible, MEP on 2,4,6-Nitrophenol. J. Phys. Chem. Funct. Mater. 2 (2), 77–86 (2019).

Heliyon, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06138.

Small, 18(4), 2106462. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202106462.

Ben Mahmoud, C., Anelli, A., Csányi, G. & Ceriotti, M. Learning the electronic density of states in condensed matter. Phys. Rev. B. 102 (23), 235130. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.102.235130 (2020).

Pandey, B. K., Pandey, S. K. & Pandey, D. A survey of bioinformatics applications on parallel architectures. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 23 (4), 21–25 (2011).

Hajam, T. A., Saleem, H., Padhusha, M. S. A. & Mohammed Ameen, K. K. Synthesis, quantum chemical calculations and molecular docking studies of 2-ethoxy-4 [(2-trifluromethyl-phenylimino) methyl] phenol. Mol. Phys. 118 (24), e1781945. https://doi.org/10.1080/00268976.2020.1781945 (2020).

Shaibuna, M., Kuniyil, M. J. K. & Sreekumar, K. Deep eutectic solvent assisted synthesis of dihydropyrimidinones/thiones via Biginelli reaction: theoretical investigations on their electronic and global reactivity descriptors. New J. Chem. 45 (44), 20765–20775. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1NJ03879F (2021).

Du John, H. V., Jose, T., Sagayam, K. M., Pandey, B. K. & Pandey, D. Enhancing Absorption in a Metamaterial absorber-based Solar cell Structure through anti-reflection Layer Integration1–11 (Silicon, 2024).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Local softness and chemical reactivity in the molecules CO, SCN – and H2CO. J. Mol. Struct. (Thoechem). 163, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-1280(88)80397-X (1988).

Demircioğlu, Z., Kaştaş, Ç. A. & Büyükgüngör, O. Theoretical analysis (NBO, NPA, Mulliken Population Method) and molecular orbital studies (hardness, chemical potential, electrophilicity and Fukui function analysis) of (E)-2-((4-hydroxy-2-methylphenylimino) methyl)-3-methoxyphenol. J. Mol. Struct. 1091, 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2015.02.076 (2015).

Becke, A. D. Densityfunctional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. doi: https://doiorg. 98 (7), 5648–5652. DOI:10.1063/1.464913 (1993). doi:10.1063/1.464913

Chandini, K. M. et al. Synthesis, crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis, DFT calculations, 3D energy frameworks studies of Schiff base derivative 2, 2′-((1Z, 1′ Z)-(1, 2-phenylene bis (azanylylidene)) bis (methanylylidene)) diphenol. J. Mol. Struct. 1244, 130910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130910 (2021).

Sharma, M., Pandey, D., Palta, P. & Pandey, B. K. Design and power dissipation consideration of PFAL CMOS V/S conventional CMOS based 2: 1 multiplexer and full adder. Silicon 14 (8), 4401–4410 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Crystal structure and noncovalent interactions of heterocyclic energetic molecules. Molecules 27 (15), 4969. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27154969 (2022).

Du John, H. V. et al. Design of Si Based nano Strip Resonator with polarization-insensitive Metamaterial (MTM) Absorber on a Glass Substrate1–10 (Silicon, 2021).

Shukla, S. et al. Vibrational spectroscopic, NBO, AIM, and multiwfn study of tectorigenin: a DFT approach. J. Mol. Struct. 1217, 128443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128443 (2020).

Saravanan, S. & Balachandran, V. Conformational stability, spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman and UV–Vis) analysis, NLO, NBO, FMO and Fukui function analysis of 4-hexylacetophenone by density functional theory. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 138, 406–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2014.11.091 (2015).

Heliyon, 6(12). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05783.

KVM, S., Pandey, B. K. & Pandey, D. Design of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Sensors for Highly Sensitive Biomolecular Detection in Cancer Diagnostics1–13 (Plasmonics, 2024).

Du John, H. V. et al. Polarization insensitive circular ring resonator based perfect metamaterial absorber design and simulation on a silicon substrate. Silicon 14 (14), 9009–9020 (2022).

Magalhães, S., Goodfellow, B. J. & Nunes, A. FTIR spectroscopy in biomedical research: how to get the most out of its potential. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 56 (8–10), 869–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/05704928.2021.1946822 (2021).

Raman, C. V. & Krishnan, K. S. A new type of secondary radiation. Nature 121 (3048), 501–502. https://doi.org/10.1038/121501c0 (1928).

Lord, R. C. Strategy and tactics in the Raman spectroscopy of biomolecules. Appl. Spectrosc. 31 (3), 187–194 (1977).

Sah, M., Khadka, M., P Lamichhane, H. & S Mallik, H. Physical Analysis of Aspirin in different phases and States using density functional theory. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32610 (2024).

Arulaabaranam, K., Muthu, S., Mani, G. & Geoffrey, A. B. Speculative assessment, molecular composition, PDOS, topology exploration (ELF, LOL, RDG), ligand-protein interactions, on 5-bromo-3-nitropyridine-2-carbonitrile. Heliyon 7 (5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07061 (2021).

Wong, B. M. & Hsieh, T. H. Optoelectronic and excitonic properties of oligoacenes: substantial improvements from range-separated time-dependent density functional theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6 (12), 3704–3712 (2010).

Dhanasekar, S., Sagayam, M., Pandey, K., Pandey, D. & B. K., & Refractive Index Sensing Using Metamaterial Absorbing Augmentation in Elliptical Graphene Arrays1–11 (Plasmonics, 2023).

Govindaraj, V. et al. Low-power test pattern generator using modified LFSR. Aerosp. Syst. 7 (1), 67–74 (2024).

Bruntha, P. M. et al. Application of switching median filter with L 2 norm-based auto-tuning function for removing random valued impulse noise. Aerosp. Syst. 6 (1), 53–59 (2023).

Jayapoorani, S., Pandey, D., Sasirekha, N. S., Anand, R. & Pandey, B. K. Systolic optimized adaptive filter architecture designs for ECG noise cancellation by Vertex-5. Aerosp. Syst. 6 (1), 163–173 (2023).

Arulaabaranam, K., Mani, G. & Muthu, S. Computational assessment on wave function (ELF, LOL) analysis, molecular confirmation and molecular docking explores on 2-(5-Amino-2-Methylanilino)-4-(3-pyridyl) pyrimidine. Chem. Data Collections. 29, 100525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdc.2020.100525 (2020).

Wong, B. M. & Cordaro, J. G. Coumarin dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells: A long-range-corrected density functional study. The Journal of chemical physics, 129(21). (2008).

Wong, B. M., Piacenza, M. & Della Sala, F. Absorption and fluorescence properties of oligothiophene biomarkers from long-range-corrected time-dependent density functional theory. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 11 (22), 4498–4508 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express gratitude to St. Xavier’s College, Maitighar, Nepal for providing the computational support.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mukesh Khadka and Manoj Sah perform experiment, wrote manuscript. Raju Chaudhary and Suresh Kumar Sahani validate results, wrote manuscript. Kameshwar Sahani and Binay Kumar Pandey conceptualized work, wrote manuscript. Digvijay Pandey perform experiment, wrote manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have ‘no known conflict of interests or personal relationships’ that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper..

Ethics approval

Not Applicable (as the results of studies do not involve any human or animal).

Consent to participate

Not Applicable (as the results of studies do not involve any human or animal).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khadka, M., Sah, M., Chaudhary, R. et al. Spectroscopic, quantum chemical, and topological calculations of the phenylephrine molecule using density functional theory. Sci Rep 15, 208 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81633-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81633-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced plasmonic biosensors with machine learning for ultra-sensitive detection

Discover Nano (2026)

-

The impact of urbanization on land use land cover change using geographic information system and remote sensing: a case of Mizan Aman City Southwest Ethiopia

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

AI-Driven intrusion detection and prevention systems to safeguard 6G networks from cyber threats

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Blockchain based electronic educational document management with role-based access control using machine learning model

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Quantum physical analysis of caffeine and nicotine in CCL4 and DMSO solvent using density functional theory

Scientific Reports (2025)