Abstract

Neuromuscular diseases (NMD) are a group of neurological diseases that manifest with various clinical symptoms affecting different components of the peripheral nervous system, which play a role in voluntary body movements control. The primary objective of this study is to explore the diagnostic efficacy of a combined genetic and biochemical testing approach for patients with neuromuscular diseases with diverse presentations in a population with high rate of consanguinity. Genetic testing was performed using selected Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) gene panels and whole exome sequencing on the peripheral blood sample from the patients. The study results revealed that the majority of patients in our cohort had a history of consanguinity (83%). Genetic testing through gene panels and Whole Exome Sequencing yielded similar result. Out of the patients tested, 66% underwent gene panels testing, 56% had Whole Exome Sequencing, 32% received array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH) assays, and 40% underwent metabolic testing. Overall, 58 patients (61%) received definitive results after following all tests. Among the remaining 36 patients, 19 exhibited variants of unknown significance (VOUS) (21%).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuromuscular diseases (NMD) are a category of neurological diseases that present a myriad of clinical manifestations affecting different components of the neuromuscular system, which is involved in the voluntary control of body movements.

NMDs are characterized by dysfunction or damage to anterior horn cells, muscles, neuromuscular junctions, or peripheral nerves1,2,3. Recently, with the advancement of genetic and metabolic testing, accompanied by the development of commercial (Next Generation Sequencing) gene panels specific for each phenotype, reaching a conclusive diagnosis has become easier than previously performed testing4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. NGS panel have become a valuable component, along with clinical examination and neurophysiologic testing, in the diagnostic work up of patients with neuromuscular diseases4,5,6,11.

From a clinician’s standpoint, choosing a test for a patient can be challenging. Cost-effectiveness in tiered testing remains an issue, and the yield of each test varies depending on numerous factors such as disease phenotype, patient population and commercial lab capabilities7,8. Whole exome sequencing (WES) has been developed to cover a large number of genes and copy number variants (CNVs), with limited depth of coverage and bioinformatics approaches. While NGS gene panels are ideal for a single clear phenotype, they have limitations due to the variability of diseases and the number of genes selected for diagnosis7,8.

The effective identification of a gene mutation relies heavily on the selection of potential markers in the gene panel. Chromosomal microarray is another method used to evaluate such cases, with results varying based on the phenotype9,10. Additionally, Biochemical testing for inborn errors of metabolism is commonly used in the pediatric population as a first-tier screening test for many conditions, but its yield in NMDs is uncertain4,11,13. In the current era of personalized medicine, it is crucial for a clinician to promptly and cost-effectively diagnose patients. In the field of neuromuscular genetics, there is limited literature on the diagnostic utility of testing7.

Consanguineous marriages, or unions between closely related individuals, are common in Saudi Arabia. The high frequency is primarily driven by cultural, social, and economic factors, such as familial cohesion and economic benefits with rates ranging from 40 to 60% depending on the region and population studied14. Such marriages can strengthen family ties, but also increase the risk of autosomal recessive genetic disorders due to the inheritance of shared deleterious alleles from common ancestors15,16.

Research on neurological disorders, including epilepsy, intellectual disabilities, and certain neurodevelopmental conditions, has shown significantly higher prevalence where the rate of consanguinity is higher17,18,19,20,21,22,23,41.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the effectiveness of genetic and biochemical testing in the context of neuromuscular diseases with varying presentations, particularly within a highly consanguineous population.

Material and methods

After obtaining approval from the institutional review board, we conducted a retrospective review of the medical records of pediatric patients seen at two subspecialized pediatric neuromuscular disorders clinics at King Fahad Specialist Hospital in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, between 2013 and 2022. We specifically focused on patients under 16 years of age who presented with primary neuromuscular symptoms such as hypotonia, difficulty walking, delayed motor milestones, high creatine kinase levels, and exercise intolerance. Patients with incomplete data, those who only underwent serologic testing and individuals who did not receive follow-up care were excluded from the study. All data were meticulously entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet by A. A. and reviewed by F.G., M. M and F.A.

Diagnosis of neuromuscular patients

The diagnosis of neuromuscular patients was based on a thorough review of patient history, physical examinations, and electrophysiological findings. Genetic testing was recommended by the attending pediatric neuromuscular neurologist and whole blood samples were collected for analysis. Patients already diagnosed with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), or Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) through targeted gene testing were excluded from our study. Additionally, patients with autoimmune myasthenia gravis, which is diagnosed through serologic testing, and with syndromic hypotonia diagnosed prior to their visit to the neuromuscular disorder clinic were also excluded.

The determination of the pathogenicity of the variants was done through genetic testing. Mutational analysis was done through the reads of selected gene panels and whole exome sequencing approaches on the peripheral blood sample from the patients.

Metabolic and genetic testing

The following data were collected to determine the effectiveness of testing in our cohort: diagnosis, consanguinity, creatine kinase levels, metabolic and genetic test results and whether they are conclusive or not. Serum metabolic testing included plasma testing of ammonia, lactate, pyruvate, acylcarnitine profile, and amino acid levels, at the discretion of the treating physician.

Urine tests included an acylcarnitine profile and amino/organic acids as deemed necessary by the treating physician. Metabolic testing was conducted biochemically at our institution. Genetic testing included tests such as chromosomal micro-array analysis (CMA) performed by CGC Genetics using the Cytoscan HD platform from Affymetrix. Hybridization results were analyzed using ChAS Software (Chromosome Suite Analysis, Affymetrix). We utilized gene panels based on presentation, whole exome sequencing, and whole genome sequencing. Some patients underwent a panel followed by whole exome sequencing (WES) in a step-wise manner, while two patients underwent WES followed by panels as recommended by their attending neurologists. Genetic tests were carried out at CGC Genetics (CGC Genetics Inc., New Jersey, U.S.A.) or Centogene (Centogene, Rostock, Germany).

Both treating pediatric neurologists and clinical geneticists reviewed all variants of uncertain significance and likely pathogenic variants in the context of the clinical phenotype. Variants were classified according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines24.

Results

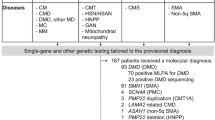

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a retrospective review of the data for 130 patients referred to the neuromuscular clinics was conducted. Of these, 36 patients were excluded due to incomplete data (n = 2), targeted gene sequencing (n = 25), serologic testing only (n = 7), or having syndromic hypotonia diagnosed elsewhere (n = 2). Ultimately, the data for the remaining 94 patients were included and analyzed as depicted in Fig. 1 flowchart.

Phenotypic Characterization revealed that, sixteen patients presented with metabolic myopathy and rhabdomyolysis (17%), fourteen with hereditary spastic paraplegia (14.8%), thirteen with hypotonia (13.8%), thirteen with congenital myopathy (13.8%), twelve with peripheral neuropathy (12.7%), eleven patients with congenital muscular dystrophy (11.7%), seven patients presented with ataxia (7.4%), four patients with congenital myasthenia (4.2%), two patients presented with a phenotype suggestive of a channelopathy (2.1%), and another two with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (2.1%) (Table 1).

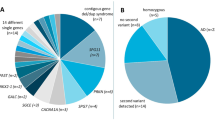

In our cohort, 78 patients had a positive family history of consanguinity (83%). 62 Patients underwent genetic panels (66%), 29 of them revealed a conclusive diagnosis (45%). Whole Exome Sequencing was done in 53 patients (56%) and was conclusive in 30 patients (56%).

Twenty-two Patients underwent both a gene panel and WES (23%) in a tiered manner; 9 (40%) of which yielded conclusive results with two had a post-WES gene panel revealed the diagnosis Thirty-one patients underwent CGH array (32%), only two of which showed abnormal results (2.1%) and nine patients had extensive regions of homozygosity, implying the high degree of consanguinity in our patient population (9.6%).

We had 37 patients who underwent metabolic testing (40%), none of them showed any conclusive results that aided in diagnosis. Overall, 58 patients (61%) had conclusive results after all testing, and in the remaining 36 patients, 20 of them showed variants of unknown significance (VOUS) (21%).

Within our patients who yielded conclusive results, we had 8 patients diagnosed with various subtypes of CMT, three patients with metabolic myopathies, and two with Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy. All the others were diagnosed with various neuromuscular diseases (see Table 1 for details). The clinical characteristics of our 18 patients who had VOUS are described in Table 2.

Discussion

Genetic testing is an important tool in the diagnostic journey of a patient with neuromuscular disease, typically starting with single gene testing if a clear diagnosis is suspected. With advances in NGS technology, commercial gene panels and WES have become the first-tier tests25,26,27,28. In our cohort, 61% of NMD patients had conclusive results and reached a definitive diagnosis.

In the clinical and practical setting, after phenotyping the patient, a clinician may choose between a commercial NGS gene panel or WES. Winder et al. tested 25,000 patients with NMDs using both targeted genes and gene panels, with a yield ranging between 4 and 33% based on the panel29. Our study showed an even higher rate of conclusive commercial panels (45%), which could potentially be due to the selection of specific gene panels in both studies or the complexity of the patient population in our tertiary-care facility.

WES has proven to be an important diagnostic tool for neuromuscular disorders, which pose a diagnostic challenge30. This increases the possibility of reaching a conclusive genetic diagnosis by identifying genes that were not previously associated with a specific NMD when other technologies have failed. It can also help exploring new genes. Furthermore, this strategy is useful for confirming a dual diagnosis in cases of complex congenital anomalies and undiagnosed cases31. Additionally, it is a cost-effective diagnostic tool that should be prioritized in the early diagnostic path of children with progressive neurological disorders32.

Previous studies have shown that WES has a yield of 49–63% in NMD patients33,34, and 52% in myopathy patients35. Our findings were similar, with 56% positive results, which is higher than gene panels. This indicates that WES can be very valuable in diagnosing patients presenting with an NMD condition and may even be used as an initial step before invasive electrophysiological testing, which can be challenging in pediatric patients.

Diagnosis of NMD is often challenging, particularly when it comes to genetic testing7. A common issue that arises during this process is the discovery of variants of unknown significance (VOUS), which was also reflected in our data (Table 2). We found that 19 patients had VOUS in commonly faced genes such as TTN, RYR1, and COL6A2. Unfortunately, this precludes patients from receiving a definitive diagnosis and requires further workup, such as segregation analysis for the parents as well as functional testing for the select variants to determine pathogenicity.

In the context of NMDs, Djordjevic et al. reported that metabolic testing can be used to screen for inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) that present with hypotonia36. It can also help diagnose metabolic myopathies, particularly fatty acid oxidation disorders, as noted by Tarnopolsky37. In some cases, it can distinguish between different types of mitochondrial diseases by the detection of various metabolites, as reported by Thompson et al.38. However, in our cohort, metabolic screening did not prove beneficial, which could be attributed to the absence of mitochondrial disorders in our patients and the fact that metabolic myopathy patients were not in crises during at the time of testing.

In contrast to a previously reported study by Piluso et al.9, the utility of CGH array was limited in establishing a diagnosis for our cohort patients. Nine out of thirty-one patients exhibited regions of excessive homozygosity, indicating a high consanguinity rate. High rates of intermarriage among relatives causing a genetic signature of consanguinity, have been strongly linked to a higher prevalence of neurological disorders in populations with excessive homozygosity15,16. Inheriting identical alleles from common ancestors can lead to an elevated risk of autosomal recessive disorders, which are particularly common in neurological diseases such as epilepsy, intellectual disabilities, and neurodegenerative conditions15,18,39,40,41. Studies have reported that consanguineous unions is associated with a greater incidence of pathogenic conditions due to this excessive homozygosity42,43,44. Homozygous deleterious alleles can contribute to both common and rare neurological disorders within consanguineous populations. This genetic phenomenon poses a significant public health concern, as the accumulation of these alleles can lead to higher prevalence of neurological disorders45,46,47.

Limitations

This study was limited by the small number of recruited patients, which mainly caused difficulties in recruiting patients and obtaining data through Electronic Medical Records (EMR). Future studies can be conducted on a multicenter level to increase the number of patients in our population.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study described the diagnostic yield of different types of genetic testing for NMD patients, in a highly consanguineous Saudi population. The yield was higher in WES than in NGS panels, with CGH array and metabolic testing showing no yield at all. These results, although limited by sample size, could favor the use of WES as a first-tier test in the work up of a patient presenting with a neuromuscular disease.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cantó-Santos, J., Grau-Junyent, J. M. & Garrabou, G. The impact of mitochondrial deficiencies in neuromuscular diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 9(10), 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9100964 (2020).

Zilio, E., Piano, V. & Wirth, B. Mitochondrial dysfunction in spinal muscular atrophy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(18), 10878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231810878 (2022).

Ponomarev, A. S., Chulpanova, D. S., Yanygina, L. M., Solovyeva, V. V. & Rizvanov, A. A. Emerging gene therapy approaches in the management of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA): An overview of clinical trials and patent landscape. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(18), 13743. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241813743 (2023).

Carter, M. et al. Room to improve: The diagnostic journey of spinal muscular atrophy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 42, 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2022.12.001 (2023).

Hammond, C. K., Oppong, E., Ameyaw, E. & Dogbe, J. A. Spinal muscular atrophy in Ghanaian children confirmed by molecular genetic testing: a case series. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 9(46), 78. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2023.46.78.32240 (2023).

Romanelli Tavares, V. L. et al. Integrated approaches and practical recommendations in patient care identified with 5q spinal muscular atrophy through newborn screening. Genes (Basel). 15(7), 858. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15070858 (2024).

Ng, K. W. P., Chin, H. L., Chin, A. X. Y. & Goh, D. L. Using gene panels in the diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders: A mini-review. Front Neurol. 12(13), 997551. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.997551 (2022).

Mansfield, C. et al. The value of knowing: Preferences for genetic testing to diagnose rare muscle diseases. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 19(1), 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-024-03160-7 (2024).

Piluso, G. et al. Motor chip: A comparative genomic hybridization microarray for copy-number mutations in 245 neuromuscular disorders. Clin. Chem. 57(11), 1584–1596. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2011.168898 (2011).

Lambrescu, I., Popa, A., Manole, E., Ceafalan, L. C. & Gaina, G. Application of droplet digital PCR technology in muscular dystrophies research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(9), 4802. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23094802 (2022).

Carter, M. T. et al. Genetic and metabolic investigations for neurodevelopmental disorders: position statement of the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists (CCMG). J. Med. Genet. 60(6), 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg-2022-108962 (2023).

Klein, C. J. & Foroud, T. M. Neurology individualized medicine: When to use next-generation sequencing panels. Mayo Clin. Proc. 92(2), 292–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.09.008 (2017).

Wayhelova, M. et al. Exome sequencing improves the molecular diagnostics of paediatric unexplained neurodevelopmental disorders. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 19(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-024-03056-6 (2024).

Albanghali, M. A. Prevalence of consanguineous marriage among Saudi Citizens of Albaha, a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20(4), 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043767 (2023).

Hamamy, H. Consanguineous marriages: Preconception consultation in primary health care settings. J. Commun. Genet. 3(3), 185–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-011-0072-y (2012).

Khayat, A. M. et al. Consanguineous marriage and its association with genetic disorders in Saudi Arabia: A review. Cureus 16(2), e53888. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.53888 (2024).

Mahrous, N. N. et al. The known and unknown about attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) genetics: A special emphasis on Arab population. Front Genet. 6(15), 1405453. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2024.1405453 (2024).

Tenorio, R. B., Camargo, C. H. F., Donis, K. C., Almeida, C. C. B. & Teive, H. A. G. Diagnostic yield of NGS tests for hereditary ataxia: A systematic review. Cerebellum 23(4), 1552–1565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-023-01629-y (2024).

Tein, I. Recent advances in neurometabolic diseases: The genetic role in the modern era. Epilepsy Behav. 145, 109338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109338 (2023).

Mahungu, A. C., Monnakgotla, N., Nel, M. & Heckmann, J. M. A review of the genetic spectrum of hereditary spastic paraplegias, inherited neuropathies and spinal muscular atrophies in Africans. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 17(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02280-2.PMID:35331287;PMCID:PMC8944057 (2022).

Bernard, R., De Sandre-Giovannoli, A., Delague, V. & Lévy, N. Molecular genetics of autosomal-recessive axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathies. Neuromolecular Med. 8(1–2), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1385/nmm:8:1-2:87 (2006).

Monies, D. et al. The landscape of genetic diseases in Saudi Arabia based on the first 1000 diagnostic panels and exomes. Hum. Genet. 136(8), 921–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-017-1821-8 (2017).

Al-Owain, M., Al-Zaidan, H. & Al-Hassnan, Z. Map of autosomal recessive genetic disorders in Saudi Arabia: Concepts and future directions. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 158A(10), 2629–2640. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.35551 (2012).

Richards, S. et al. Rehm HL Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. 17(5), 405–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.30 (2015).

Chi, C. S., Tsai, C. R. & Lee, H. F. Resolving unsolved whole-genome sequencing data in paediatric neurological disorders: A cohort study. Arch. Dis. Child. 109(9), 730–735. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2024-326985 (2024).

Lionel, A. C. et al. Improved diagnostic yield compared with targeted gene sequencing panels suggests a role for whole-genome sequencing as a first-tier genetic test. Genet. Med. 20(4), 435–443. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.119 (2018).

Runheim, H. et al. The cost-effectiveness of whole genome sequencing in neurodevelopmental disorders. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 6904. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33787-8 (2023).

Stavropoulos, D. J. et al. Whole genome sequencing expands diagnostic utility and improves clinical management in pediatric medicine. NPJ. Genom. Med. 13(1), 15012. https://doi.org/10.1038/npjgenmed.2015.12 (2016).

Winder, T. L. et al. Clinical utility of multigene analysis in over 25,000 patients with neuromuscular disorders. Neurol Genet. 6(2), e412. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXG.0000000000000412.PMID:32337338;PMCID:PMC7164976 (2020).

Meyer, A. P. et al. Exome sequencing in the pediatric neuromuscular clinic leads to more frequent diagnosis of both neuromuscular and neurodevelopmental conditions. Muscle Nerve 68(6), 833–840. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.2797 (2023).

Piñeros-Fernández, M. C. et al. Utility of exome sequencing for the diagnosis of pediatric-onset neuromuscular diseases beyond diagnostic yield: A narrative review. Neurol. Sci.: Off. J. Italian Neurol. Soc. Italian Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 454, 1455–1464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-023-07210-z (2024).

Aaltio, J. et al. Cost-effectiveness of whole-exome sequencing in progressive neurological disorders of children. Eur. J. Paediatric Neurol.: EJPN: Off. J. Eur. Paediatric Neurol. Soc. 36, 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2021.11.006 (2022).

Chae, J. H. et al. Utility of next generation sequencing in genetic diagnosis of early onset neuromuscular disorders. J. Med. Genet. 52(3), 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102819 (2015).

Chen, P. S. et al. Diagnostic challenges of neuromuscular disorders after whole exome sequencing. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 10(4), 667–684. https://doi.org/10.3233/JND-230013 (2023).

Babić Božović, I. et al. Diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in myopathies: Experience of a Slovenian tertiary centre. PLoS One 16(6), e0252953. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252953 (2021).

Djordjevic, D., Tsuchiya, E., Fitzpatrick, M., Sondheimer, N. & Dowling, J. J. Utility of metabolic screening in neurological presentations of infancy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 7(7), 1132–1140. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51076 (2020).

Tarnopolsky, M. A. Metabolic myopathies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 28(6), 1752–1777. https://doi.org/10.1212/CON.0000000000001182 (2022).

Thompson, R. et al. Advances in the diagnosis of inherited neuromuscular diseases and implications for therapy development. Lancet Neurol. 19(6), 522–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30028-4 (2020).

Strømme, P. et al. Parental consanguinity is associated with a seven-fold increased risk of progressive encephalopathy: A cohort study from Oslo, Norway. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 14(2), 138–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.03.007 (2010).

Alaamery, M. et al. Case report: A founder UGDH variant associated with developmental epileptic encephalopathy in Saudi Arabia. Front Genet. 16(14), 1294214. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1294214 (2024).

Tenorio, R. B., Camargo, C. H. F., Donis, K. C., Almeida, C. C. B. & Teive, H. A. G. Diagnostic yield of NGS tests for hereditary ataxia: A systematic review. Cerebellum 23(4), 1552–1565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-023-01629-y (2024).

Hu, H. et al. Genetics of intellectual disability in consanguineous families. Mol. Psychiatry 24(7), 1027–1039. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-017-0012-2 (2019).

Harripaul, R. et al. Mapping autosomal recessive intellectual disability: Combined microarray and exome sequencing identifies 26 novel candidate genes in 192 consanguineous families. Mol. Psychiatry 23(4), 973–984. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.60 (2018).

Ghasemi, M. R. et al. Exome sequencing reveals neurodevelopmental genes in simplex consanguineous Iranian families with syndromic autism. BMC Med. Genom. 17(1), 196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-024-01969-6 (2024).

Alkuraya, F. S. Homozygosity mapping: One more tool in the clinical geneticist’s toolbox. Genet. Med. 12(4), 236–239. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ceb95d (2010).

Alkuraya, F. S. Discovery of rare homozygous mutations from studies of consanguineous pedigrees. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 75(1), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142905.hg0612s75 (2012).

Tuncay, I. O. et al. Analysis of recent shared ancestry in a familial cohort identifies coding and noncoding autism spectrum disorder variants. NPJ. Genom. Med. 7(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-022-00284-2 (2022).

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman center For Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2024–307.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.-H. and F.A., M.A., F.A., and S.A.-D. collected the data. A.A.-H. and S.B. analyzed the data. A.A.-H., F.A., M.A., F.A., S.A.-D., D.N.B., and S.B. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s) for participation. The study was carried out in accordance with the code of international and local Ethics (Declaration of Helsinki). This study was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee of the King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam (Dammam, Saudi Arabia).

Patient consent for publication

The parents of the patient provided written informed consent for publication.

Ethical publication statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Hedaithy, A., Alghamdi, F., Almomen, M. et al. Comparative genetic diagnostic evaluation of pediatric neuromuscular diseases in a consanguineous population. Sci Rep 15, 231 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81744-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81744-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Diagnostic impact of whole exome sequencing in neurometabolic disorders in Syrian children: a single center experience

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2025)