Abstract

Lead (Pb) exposure negatively impacts fertility in both males and females, pregnancy outcomes, and child brain development. We investigated the reproductive and neurological effects of Pb exposure on male and female mice via Pb-contaminated soil for 4 weeks. Breeding was conducted after completion of exposure, in four groups; group 1 consisted of exposed dams and unexposed sires, group 2 consisted of exposed sires and unexposed dams, group 3 consisted of exposed sires and exposed dams and group 4 was the control. Generally, Pb exposure reduced observed conception rates, with a cumulative decrement observed when both males and females are exposed. Gene expression of the testes revealed oxidative stress as the cause of reduced conception rates. Neurological tests: Morris water maze and rotarod were conducted on F1 generation offspring. Maternally and paternally exposed F1 mice performed poorly in the Morris water maze when compared to the control. The severity of the neurological effects was also parent-dependent and sex-dependent. Paternal Pb exposure effects were more pronounced in female offspring. A comparison of gene expression changes of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex showed paternal Pb-exposure resulted in more prefrontal cortex changes than in the hippocampus, a trend also recorded in the exposed sires. The pronounced effects in female offspring of paternal Pb exposure may suggest that Pb neurological effects may be X-chromosome-linked.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lead (Pb) toxicity remains endemic in many places of the world with routes of exposure varying from country to country1. Metals like Pb are concentrated into soil mainly by anthropogenic processes that include manufacturing, smelting and industrial processes2. Lead contaminated soil is one of the major sources of exposure, where like other heavy metals Pb does not biodegrade hence persisting in the soil3.

Lead exposure has been associated with impairment of renal, haematopoietic and hepatic systems in children making it a global health concern4. It has also been attributed to the cause of reduced fertility, pregnancy loss and neonatal fatalities. In men it is known to reduce libido, sperm viability and quality5 as well as reduced levels of testosterone6. Effects on the brain can be detrimental, causing neurological impairment such as reduction in IQ, learning deficits, cognitive impairments, and memory loss7. This is more pronounced in children as the developing brain is more susceptible to the effects of Pb when it comes to learning than an already developed adult brain8.

Although numerous studies9,10,11 have focused on maternal exposure and the consequent neurological defects that occur when exposure is gestational12, there has been an increase in the investigation of paternal inherited neurological diseases. This is critical as occupational Pb exposure mostly occurs in men13. In an earlier study in humans, an association was noted between paternal Pb exposure and low birth weight and length14 Since paternal exposure affects overall mass development of neonates, information on the possibility that brain development may be affected is lacking. Therefore, in the current study, we investigated if Pb exposure would cause neurological deficits via paternal exposure.

To fully distinguish these effects, we compared the effects of Pb exposure on conception, depending on whether sires or/and dams were exposed in F0. Male fecundity was evaluated using Serine inhibitor Kazal type 2 (Spink 2), cysteine-rich secretory protein 2 (Crisp2) and Pou5F1. To determine how differently the above exposures in F0 individuals would affect the F1 generation, we used neurological tests (water Morris and rotarod tests) and brain plasticity-related biomarkers (brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf), cAMP response element binding protein (Creb), N-methy-D-aspartate receptors (Grin2A and Grin2B) in hippocampal and prefrontal cortex tissues.

Methodology

Soil preparation

Soil containing lead sulphide at concentration 5000 mg/kg was selected according to environmental concentrations recorded by Nakata et al.15 and Wade et al.16. The soil was prepared two weeks before the onset of the exposure experiment. Soil was sieved to 2 mm diameter and Pb was added and left to mature. The control group was kept on Pb-free soil. The soil was changed weekly in both exposed and control groups. All the mice in the current experiment including F1 generation were kept on soil.

Animals

The current study was conducted under the ethical considerations approved by Hokkaido University, approval number (22-0092) which is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International). This animal experiment complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments). ARRIVE check list is attached in the Supporting Information. Twenty-one male and 42 female C57BL/67 mice aged 4 weeks old were obtained from Japan SLC Co. Ltd, weighing between 17 and 22 g. Males and females were kept in separate cages and fed standard rodent pellets; water was administered ad libitum. After 1 week of acclimatisation, the mice were randomly divided into Pb-exposed and control groups.

Exposure on lead contaminated soil lasted for 4 weeks, after which mice were kept on clean soil, and breeding was then conducted. Sires and dams were kept together for a week, after which all sires were euthanised. All mice in this experiment were euthanised using a carbon dioxide chamber under the American Veterinary Medical association (AVMA) guidelines. The dams were euthanised after F1 pups were weaned. Fifteen of the F1 pups were kept for neurological tests as representatives of each group. Of these, nine were male and six were female, this number was selected according to the resultant number and sexes present at weaning in each group. Neurological tests were conducted when these F1 mice were 8 weeks old, as shown in Fig. 1.

Fertility study

Breeding was conducted by keeping males and females in cages at the ratio of 1:2, estrus had been induced prior in females using the Whitten effect17. The mice were divided into four groups. Group 1 consisted of unexposed sires and exposed dams, Group 2 consisted of exposed sires and unexposed dams, Group 3 had exposed sires and exposed dams, and Group 4 was the control with unexposed sires and dams. After euthanising of sires, dams were observed for pregnancy and were kept in pairs for companionship until a week prior to the expected day of partition when single housing was used. Pups were weighed from weaning till 8 weeks old and weights were recorded.

Water Morris test F1

Eight-week-old mice were subjected to the Water Morris test as described by Tian et al.18 with a few modifications. Mice were trained for four days, and the probe test was performed on day five.

Rotarod test

Rotarod test was conducted on F1 generation using specially manufactured mice Rotarod by Panlab. Mice were taken to the testing room and left to acclimate for one hour before the beginning of the experiment. The mice were put on rotarod while speed was gradually increased, each trail had an endpoint of 300 s. It was noted if the mouse jumped off or fell during each trail. After one training trial, each mouse was subjected to three trials with resting intervals of fifteen minutes.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the brain’s prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and testis samples using FastGene® kit (Nippon Genetics). cDNA was made using Toyobo cDNA synthesis kit. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was used to quantify the expression levels of different genes, using Beta actin mRNA as the normalization standard. Primers used are shown in Supplementary data Table S4.

Lead measurement

Brain and bone samples were weighed and dried for 48 h at 50 °C. Dried samples (20–100 mg) and 0.1 ml of blood were then added to 5 ml of 30% nitric acid (Cica reagent, Specific gravity of 1.38, 60%; Kanto Chemical Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and 1 ml of hydrogen peroxide (Cica reagent, 30%; Kanto Chemical Corp.). These were then digested in a speed wave microwave (Berghof, Eningen, Germany). Solutions from this process were analysed for Pb concentrations using inductively coupled mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, 7700 series; Agilent Technologies, Tokyo, Japan). Analytical quality control was conducted using DOLT-5 (dogfish liver; National Research Council of Canada) and NIST 1400 Bone Ash (Stigma Aldrich; United States of America) as certified reference materials. The recovery rates in replicate measurements yielded were 96–100% for DOLT-5 and 86–90% for Bone Ash.

Statistical analysis

Results were subjected to student’s t-Test for F0 and ANOVA for F1. Assessing differences among group means was done by using Tukey’s test. Data has been presented as mean ± S.E.M. and p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical studies were done using JMP version 16.

Results

Breeding results

The conception rate dropped when either sires or dams were exposed to Pb. The conception rate was lesser when sires were exposed than when dams were exposed, but these rates were not significantly different from control breeding rates. The conception rate was less than 50% (Table 1) when both sires and dams were exposed to Pb, and this value was statistically significant when compared to the pregnancy rate in the control group.

Lead concentrations in F0

Eleven exposed sire mice and 10 control sire mice had blood and bone Pb levels measured at the end of the breeding period. The bone Pb mean value was 15.6 mg/kg and other values ranged from 26.7 to 6.13 mg/kg (Fig. 2A). In the blood, the exposed sires’ mean Pb level was 5.73 µg/dl, levels ranged from 8.19 to 2.96 µg/dl (Fig. 2B). In the Control group, Pb levels in the bone ranged from 0.498 to 0.0905 mg/kg with a mean value of 0.287 mg/kg, while those in the blood ranged from 0.498 to 0.227 µg/dl with a mean value of 0.367 µg/dl. Twenty-one control dams and 20 exposed dam’s bone and blood Pb levels were measured upon weaning of F1 offspring. One exposed dam experienced dystocia during parturition and was then excluded from further analysis. Exposed dams bone Pb levels ranged from 12.4 to 7.25 mg/kg with a of mean of 9.82 mg/kg (Fig. 2C). Blood Pb levels ranged from 1.57 to 13.9 µg/dl with a mean of 2.65 µg/dl (Fig. 2D). In the control group the bone Pb levels ranged from 0.382 to 0.131 mg/kg with a mean value of 0.187 mg/kg. The blood lead levels were ranged from 0.738 to 0.100 µg/dl with a mean of 0.515 µg/dl.

A comparison of Pb levels was made between exposed pregnant dams and non-pregnant exposed dams to determine the effect of pregnancy and lactation on Pb distribution in the bone and blood (Fig. 3). The results did not show any significant differences in bone lead as both pregnant exposed dams and non-pregnant dams had similar means of 9.73 mg/kg and 9.91 mg/kg, respectively (Fig. 3A). The blood Pb levels showed significant differences with pregnant dams having mean Pb levels of 1.94 µg/dl and non-pregnant dams having 3.35 µg/dl (Fig. 3B).

F1 generation mice are described by the exposure status of the parents, such offspring born from only exposed dams are termed the Dam exposed group, and those from control dams and sires are termed Control. The offspring from exposed sires are Sire exposed and those from exposed sires and dams are referred to as Both exposed group.

F1 generation weights, litter sex ratios and blood Pb levels are presented in supplementary materials.

Water Morris test

The water Morris Test Latency to escape showed a steady decrease in the times in all groups of F1 female offspring (Fig. 4A), there was an increase in time recorded on Day 4 in all groups when compared to Day 3. In Sires exposed group offspring, the learning trend differed from the other groups in that it had an inconsistent pattern. On all training days, significant differences occurred between the Control group and Dam exposed group.

In F1 females distance covered during latency to escape was measured (Fig. 4B) this was the distance the mice swum around until they found the escape platform. There were no significant differences among the groups. It is expected during the test for distance to gradually reduce during the training. There was a downward trend in the distance until Day 3 and a sharp increase in the distance was observed on Day 4 which is also seen in the latency to escape analysis.

During the training of the water Morris maze test the F1 males (Fig. 5A) showed a constant steady decrease in latency to escape time, except for the Both exposed group whose time increased on Day 4. There were no significant differences among the timings in the groups. The distance travelled during latency to escape was measured in F1 males (Fig. 5B), the Dam exposed and Both exposed groups had timings increase on Day 4 similar to the trend observed in F1 females, while Sire exposed, and Control groups showed the downward expected trend in the distance covered.

The probe test (Fig. 6) was conducted to fully understand the spatial learning ability. F1 females showed no significant differences in probe entries and time spent in the target zone (Fig. 6B,C). There was a significant difference observed between Sire exposed females and Control with regards to the latency to escape (Fig. 6A). In F1 males the probe test did not yield any notable or significant differences among the groups (Fig. 6D–F). The test statistics were comparable among all the groups.

Shows the results of the probe test for F1 females and F1 males. (A,D) Shows latency to escape during probe test (*p-value = 0.01), (B,E) shows entries into target zone and (C,F) shows time spent in target zone in F1 females and F1 males, respectively. (n = 6 in each group in F1 females and n = 9 in each group in F1 males).

Rotarod test

The F1 females’ rotarod results showed significant differences in the highest speed attained and time spent on the rod (Fig. 7A, B) among the groups. With regards to speed, the Control group and the Dam exposed group had attained the highest speed. There were significant differences between the Control group and Sire exposed group. The Sires exposed group attained the least speed and spent the lowest amount of time on the rotarod. The Dam exposed group female mice spent the most time on the rotarod. This was comparable to Control, however, there were significant differences when compared with those of the Sire exposed and Both exposed groups on the total time spent on the rotarod.

The rotarod test in F1 males did not show any differences among the groups (Fig. 7C,D), the male offspring from Pb exposed groups performed comparably to those of the control group. The F1 males when compared to the F1 females spent less time on the rotarod and had attained a lesser speed.

Lead concentrations in F1

Lead concentrations were measured in F1 generation at four weeks old when excess mice were culled and at 9 weeks old after completion of neurological tests. The Both exposed group had only 7 females at weaning and hence none were culled at 4 weeks old and Pb concentrations are not presented.

In Female F1 mice there were no significant differences in the Pb concentrations among the groups at both 4 weeks old and 9 weeks old (Fig. 8A,C). At 4 weeks the bone Pb levels ranged from 0.106 to 0.0921 mg/kg for the Control and the Sire exposed groups with means of 0.112 and 0.0992 mg/kg respectively. While the Dam exposed group had a range of 0.643 to 0.0542 mg/kg with mean of 0.32 mg/kg. At 9 weeks Control, Dam exposed, and Sire exposed groups had range Pb levels from 0.272 to 0.0903 mg/kg with means of 0.166 mg/kg, 0.180 mg/kg, and 0.140 mg/kg, respectively. While Both exposed had a with mean value of 0.23 mg/kg with a range from 0.338 to 0.148 mg/kg.

shows lead levels in the bone and blood of F1 Females and F1 males. (A,B) Represent bone lead levels at 4 weeks old in F1 females and males respectively, while (C,D) are the bone lead levels at 9 weeks old. (n = 3 in each group at 4 weeks in both F1 females and F1 males), (At 9 weeks n = 6 in each group in females and n = 9 in each group in males). *p-value = 0.03. The Both exposed group had only 7 females at weaning and hence none were culled at 4 weeks old and Pb concentrations are not presented.

In the F1 males bone lead levels at 4 weeks old (Fig. 8B) were significantly different between Control and Both exposed groups, as well as the Sire exposed and Both exposed groups. Lead levels at 4 weeks ranged from 0.119 to 0.0970 mg/kg for both the Sire exposed and Control groups with means of 0.111 to 0.100 mg/kg respectively. The Both exposed group had Pb levels ranging from 0.573 to 0.26 mg/kg, with a mean of 0.385 mg/kg. The Dam exposed group values ranged from 0.248 to 0.393 mg/kg. At 9 weeks old (Fig. 8D) Pb concentration levels ranged from 0.115 to 0.358 mg/kg for all groups. The mean for the Control group was 0.164 mg/kg while the mean for the Sire exposed group was 0.132 mg/kg. The Dam exposed and Both exposed had bone Pb mean levels of 0.235 mg/kg and 0.268 mg/kg respectively.

Gene expression

Testicular genes

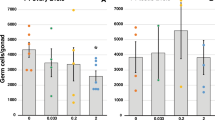

Gene expression levels of Pou5F1, Crisp2, Spink 2, and Nrf2 were analysed from testicular tissue of F0 sires (Fig. 9). Pou5F1, Crisp2, and Spink 2 were non-significantly downregulated in the exposed sire, while Nrf2 was significantly upregulated. This implies that gene expression levels of genes related to sperm production did not differ from sires of the control group, however, upregulation of Nrf2 showed the presence of oxidative stress.

shows fertility and oxidative stress associated genes expression levels in sire testicular tissue. (A) Shows Pou5F1 gene expression, (B) shows Crisp2 expression, (C) shows Spink2, (D) shows Nrf2 expression in the testicular tissue of F0 sires. *p-value = 0.02. Sires’ brain expression genes and Keap1 are shown in the supplementary material.

Brain genes

Female F1 mice brain prefrontal cortical gene expression (Fig. 10) revealed upregulation of Bdnf significantly in Dam exposed, the Sire and Both exposed groups. Creb appeared to be upregulated non-significantly in the Sire exposed and Both exposed groups. NMDA Grin2A gene was upregulated significantly in the Dam exposed female offspring and non-significantly in Both exposed group. There was a corresponding significant downregulation of NMDA Grin2B in the Dam exposed and Both exposed groups.

In the hippocampus (Fig. 11) Grin2A was significantly upregulated in the Sire exposed and Both exposed groups while Grin2B was normally regulated in among the groups. Bdnf was normally regulated among all groups, however, creb expression levels were significantly downregulated in the Dam exposed and Both exposed groups.

In F1 males prefrontal cortex, (Fig. 12) Bdnf and Creb expression levels from offspring of Pb-exposed individuals were comparable to Control. Grin2A was non-significantly upregulated in the Sire exposed group, in the Dam exposed group and the Both exposed group Grin2A was significantly upregulated. There was normal regulation of Grin2B gene in Dam exposed, Sire exposed, and Both exposed groups.

In the hippocampus (Fig. 13), Creb expression levels were significantly downregulated in the Dam exposed males so was Grin2A. The other groups had normally regulated gene expression levels for Grin2A, Grin2B, and Creb.

Discussion

We conducted a Pb exposure experiment using soil as a medium of exposure to mimic environmental exposure through inhalation and ingestion. We investigated whether lead effects are sex-dependent concerning conception in the F0 generation and neurological deficits in the F1 generation.

F0 generation

Lead exposure lowered the conception rate in our study, this was seen when either or both males and females were exposed to Pb pre-breeding. This reduction was by 20% when only dams were exposed in our study, and by 55% when both sires and dams were exposed. Infertility caused by Pb is well studied and is known to be caused by various mechanisms. In females, a study by Gerald et al.19 reported that a 10% increase in Pb blood levels led to a 6.75% decrease in concentration of oestradiol. A study by He et al.20 showed that Pb-exposed female quails showed fewer and smaller follicles than the control group of that study. Thus, Pb can lead to the reduction of the overall number of ovulations occurring. Due to our experimental design, we were unable to conduct any fertility tests on the dams. However, we presume these may have been the causes for the reduced fertility rates when females were exposed.

Results from the current study showed that male Pb exposure lowered the conception rate more than female exposure. This could be because testicular tissue is more vulnerable to Pb damage than other body tissue21. Lead damages spermatozoa, and damaged sperm DNA negatively affects embryo quality in early development, this may affect implantation and pregnancy outcomes22. Therefore, in our study even if fertilisation had occurred successfully, implantation could have failed, or the resultant embryo could have not been able to survive when the fertilising sperm had undergone DNA damage. Because Pb male exposure has an impact on early embryonic development, it has a higher factor than females in resultant of pregnancy.

Additionally, in our study like that of Dolati et al.23 Crisp2 mRNA expression levels did not significantly differ between our sire control and sire exposed groups. This was observed for Pou5F1 gene as well. Spink2 gene expression was also non-significantly downregulated in our results. This implies that the cause of the reduction in conception in this experiment could have not been mainly due to impaired sperm production as these genes are closely related to maintaining normal sperm production. However, the significant upregulation of Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) in the testicular tissue in our experiment indicates the presence of oxidative stress, which was comparable to the findings of Wang et al.24. Increased expression of the Nrf2 is well known for its cellular xenobiotic and oxidative stress response25,26,27.

Therefore, oxidative damage could have damaged sperm in the sire exposed groups, where an increase in sperm reactive oxygen species that overwhelmed the antioxidant response in Pb exposure could have caused the sperm damage28.

Damage to sperm DNA also prevents the affected sperm from being able to go through normal demethylation required in early mammalian development29. This demethylation is a protective mechanism that prevents certain parental epigenetic changes from being transferred to the next generation. Thus, failure of this mechanism provides a means through which exposed sire could cause deficits in the next generation. Secondly, it has been shown by Yamazaki et al.30 that Pb exposure causes genomic-wide DNA methylation changes in a study conducted in dogs. Takahashi et al.31 went further to demonstrate how such epigenetic changes could be transmitted via generations, where artificially generated epigenetic changes that were inserted into the genome were inherited up to two generations down from the initial mutant group. This change was able to elude the process of global demethylation that occurs in mammalians after fertilisation. Consequently, demonstrating how paternal epigenetic changes could be passed on to the next generation who are not exposed to the original trigger.

Lead levels in the blood of pregnant mice were significantly lower than those that did not get pregnant. Similarly, a study done in postmenopausal women found that nulliparous women tended to have higher lead in their blood than women who had been pregnant32. This may be due to the transplacental transfer of Pb to the developing foetus during gestation. However, the Pb levels in the bone, which represents Pb storage, did not show any significant difference between the pregnant exposed and the non-pregnant exposed groups at weaning of F1 pups. Lead is known to mobilise from the bone during pregnancy and lactation, evidence of Pb metabolism changes during pregnancy, with effects being more severe when calcium deficiency occurs. Lead mobilisation from the bone is more extensive during the postpartum period when more calcium is needed for lactation33. Therefore, we expected to record a significant difference in the bone Pb levels. However, the short exposure time in our study could have affected lead deposition levels. In addition, in the maternal blood, 99% of Pb is bound to red blood cells and only 1% is available for transplacental transfer34, therefore the Pb transfer to the foetus is dependent on this free Pb. Which in relation to the amount of Pb circulating in the mother’s body is a small amount. Furthermore, in the kidneys, Pb is absorbed in the proximal tubules and very little is excreted in urine35. The body then tends to retain more Pb than it excretes therefore even though Pb is mobilised in pregnancy it is not exclusively excreted. We assume that mobilisation of Pb from the bone does not equal to its elimination, as a result, there was no significant difference in the bone Pb levels between Pb-exposed pregnant dams and non-pregnant dams.

F1 generation

In our study, a litter sex ratio differentiation was seen in the offspring of Pb-exposed individuals. The number of female offspring reduced with Pb exposure when compared to control. We also observed stunted offspring occurring exclusively in the Dam exposed group and only in males. Literature on Pb exposure sex ratio differentiation is contradictory, but there is a strong association between Maternal health status and stunting in offspring36. Stunting effects were not prevalent when sire exposure was involved as expected. These stunted mice’s body condition improved immediately after weaning summing up the association between Pb exposure and stunting as confirmed by previous studies37. The severity of the effects that offspring develop from parental exposure is dependent on the sex of that parent.

Neurological tests

Maternally gestationally exposed F1 mice showed learning impairment during the water maze test, which was similar to a study done by Guilarte et al.38. The rats in that study showed similar levels of Pb to control when maze tests were being conducted. This was observed in our study as well, we deduce that most of the Pb had been excreted by the time of neurological tests. In fact, Pb levels in F1 generation in our experiment range below the acceptable levels of 3.5 µg/dl39 for both 4 weeks and 9 weeks old. Therefore, once Pb has caused some neurological injury, those insults remain even after the Pb has been excreted and Pb levels can be considered normal.

Interestingly, our study also showed learning impairment in mice born from exposed sires, with female offspring of exposed sires showing significant differences with control during the probe test. This was not seen in the males of the same group. The males of the Sire exposed group and the Dam exposed group performed better in the water Morris test than the females. These results were similar to what was reported by40 where the males outperformed the females.

Rotarod results revealed that male mice from exposed parents did not show any significant differences when compared to control, whereas the females overall did better than the males in motor coordination. Nevertheless, there were some significant differences among the female groups, astoundingly Dam exposed offspring were able to spend the most time on the rotarod. This may be due to the significant upregulation of Bdnf in the prefrontal cortex seen in this group, which plays an important role in transmission and plasticity in the motor cortex, subcortical motor structures and motor skill learning41. Motor skill learning requires the secretion of Bdnf to augment synaptic plasticity. These may explain why the Dam expose group was able to perform better in the rotarod as compared to the control. The levels of Bdnf were also significantly upregulated in females of Sire exposed and Both exposed groups, we speculate this may be due to the protective role of oestrogen from Pb and positive feedback of oestrogen on Bdnf42. This is observed mostly in the prefrontal cortex, oestrogen has a huge effect during sexual maturation, which is within the period when neurological tests were conducted, and samples taken.

Gene expression

In our study, expression levels of genes of interest Grin2A, Bdnf, and Creb (Fig. 14) showed more of an upregulation trend in the prefrontal cortex which is similar to study by Sánchez-Martín et al.43. Grin2A was upregulated significantly in Dam exposed group in both F1 males and Females. It was non-significantly upregulated in the Both and Sire exposed groups in F1 females. This upregulation agrees with the findings of Sánchez-Martín et al.43. Lead reduces expression levels of Glu2A protein in chronic exposure44 thereby leading to the overexpression of Grin2A as a compensatory mechanism. This may explain why Grin2A was upregulated, which was also seen in our exposed sires where it is non-significantly upregulated. Increasing expression levels of Grin2A have been associated with neurological abnormalities while upregulation of Grin2B has been shown to improve performance in spatial memory tests in mice45. In gestationally Pb-exposed F1 females, Grin2B was downregulated this was not observed in the F1 males of the same group. The downregulation of Grin2B may have led to the poor performance seen in females. The upregulation of Bdnf in females may probably have led to be downregulation of Grin2B seen in our experiment. This is because, Bdnf ensures maturation of NMDA receptors from Glu2B subunits to Glu2A by increasing expression of Grin2A (Fig. 15) after birth46,47. The upregulation of Bdnf may have indirectly led to the downregulation of Grin2B due to this mechanism.

(A) Shows a heatmap of gene expression comparison between hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in F1 females, where C represents prefrontal cortex and H for hippocampus. (B) Shows a heatmap of gene expression comparison between hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in F1 males, where C represents prefrontal cortex and H for hippocampus.

Downregulation of Creb in F1 gestationally exposed males and females in the hippocampus and paternal prefrontal cortex48 was observed in this experiment.

The binding affinity and downstream effects on NMDA receptors are sexually dimorphic, this makes interpretation of NMDA-dependent effects on synaptic plasticity complicated49. Therefore, the gene expression of NMDA subunits in the males and females is not expected to be comparable. Additionally, Pb exposure during development alters gene expression in many transcripts and regulatory genes, these effects are modified by sex. The differences that occur are dependent on how much regulatory networks are distinct between males and females50.

The relationship between the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex is intricate. For new memories to be formed, the hippocampus is required however for the replay sequence to occur the prefrontal cortex needs to coordinate. The prefrontal cortex creates a context for representations that link related memories. This implies that even gene expression may be normally regulated in the hippocampus, if the prefrontal cortex is not functioning normally some memory deficits will occur as seen in our F1 females from exposed sires51,52.

In our experiment, the exposed sires had more prefrontal cortex gene expression changes than hippocampal due to postnatal exposure. Postnatal lead exposure leads to prefrontal cortex changes rather than hippocampal changes as the prefrontal cortex is more sensitive to modifications postnatally53. Female offspring of these sires also showed a similar trend in gene expression. From this result, we assume that Pb neurotoxic developmental effects may be X chromosome linked. Furthermore, the brain expresses more X chromosome linked genes than other organs54. Other studies55,56,57,58 also explain how inheritance of certain paternal origin occurs only in female offspring. Wells59, then described how paternally inherited genes become expressed in F2 as they become maternal genes in their female offspring and can be inherited by both F2 female and male (Fig. 16).

Conclusion

Lead exposure in paternal sires affected the neurological development of the offspring as their behaviour and gene expressions mimic those of maternal exposure without showing higher Pb levels than control. We also established that Pb exposure had caused oxidative stress in testes which we presume subsequently caused defects in embryos through the damaged sperm DNA. This damage to sperm could have caused failure of global demethylation mechanism which provides a means through which exposed sires could cause deficits in the next generation by transfer of Pb-related epigenetic changes. These hypotheses, however, need to be further studied, to fully understand how this occurs in Pb exposure.

Finally, although differences were observed in learning during the training period of the water Morris Test, probe test revealed no significant differences among the F1 male groups. In F1 females’ differences were seen, but these were not statically significant in all the groups. Gene expression differed between the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus with prefrontal showing more upregulation trend. Cessation of exposure pre-breeding showed improvements seen mostly in F1 males. Inter-generational effects of Pb are parent-dependent, X-chromosome-linked, and the severity of the resultant neurological impairments are sex-dependent.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Obeng-Gyasi, E. Sources of lead exposure in various countries. 34, 25–34 (2019).

Schachter, A. E., Gailey, A., Egendorf, S. P. & Mielke, H. W. Mechanisms of children’s soil exposure. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 50, 100742 (2020).

Singh Sidhu, G. P. Heavy metal toxicity in soils: sources, remediation technologies and challenges. Adv. Plants Agric. Res. 5, (2016).

Rawat, P. S., Singh, S., Zahid, M. & Mehrotra, S. An integrated assessment of lead exposure in children: Correlation with biochemical and haematological indices. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 68, (2021).

Kumar, S. Occupational and environmental exposure to lead and reproductive health impairment: An overview. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 22, 128 (2018).

Tutkun, L., Iritas, S., Ilter, H., Gunduzoz, M. & Deniz, S. Effects of occupational lead exposure on testosterone secretion. Med. Sci. Int. Med. J. 886. https://doi.org/10.5455/medscience.2018.07.8880 (2018).

Santa Maria, M. P., Hill, B. D. & Kline, J. Lead (Pb) neurotoxicology and cognition. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child. 8, 272–293 (2019).

Soodi, M., Naghdi, N., Sharifzadeh, M., Ostad, S. N. & Abdollahi, M. Effect of Lead (Pb 2+ ) Exposure in Female Pregnant Rats and Their Offspring on Spatial Learning and Memory in Morris Water Maze. (2008).

Liu, J. et al. Lead exposure at each stage of pregnancy and neurobehavioral development of neonates. Neurotoxicology 44, 1–7 (2014).

Jia, Z. et al. Prenatal lead exposure, genetic factors, and cognitive developmental delay. JAMA Netw. Open 6, E2339108 (2023).

Shah-Kulkarni, S. et al. Neurodevelopment in early childhood affected by prenatal lead exposure and iron intake. Medicine (United States) 95, (2016).

Bazrgar, M., Goudarzi, I., Lashkarbolouki, T. & Elahdadi Salmani, M. Melatonin ameliorates oxidative damage induced by maternal lead exposure in rat pups. Physiol. Behav. 151, 178–188 (2015).

Balachandar, R., Bagepally, B. S., Kalahasthi, R. & Haridoss, M. Blood lead levels and male reproductive hormones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Toxicology 443, 152574 (2020).

García-Esquinas, E. et al. Newborns and low to moderate prenatal environmental lead exposure: Might fathers be the key?. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 21, 7886–7898 (2014).

Nakata, H. et al. Interdisciplinary approach to addressing lead pollution caused by mining activity in Kabwe, The Republic of Zambia. Environ. Monit. Contam. Res. 2, 20220004 (2022).

Wade, A. M. et al. Urban-soil pedogenesis drives contrasting legacies of lead from paint and gasoline in city soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 7981–7989 (2021).

Koyama, S. Primer effects by conspecific odors in house mice: A new perspective in the study of primer effects on reproductive activities. Horm. Behav. 46, 303–310 (2004).

Tian, H. et al. Analysis of learning and memory ability in an alzheimer’s disease mouse model using the morris water maze. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, (2019).

Gerald, A. C., Ganapathy, S., Zhu, J. & Wei, Y. Exposure to endocrine-disrupting metals and serum estrogen levels among US women. Reprod. Toxicol. 118, (2023).

He, Y., Wang, L., Li, X. & Zhao, H. The effects of chronic lead exposure on the ovaries of female juvenile Japanese quails (Coturnix japonica): Developmental delay, histopathological alterations, hormone release disruption and gene expression disorder. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 205, (2020).

Fan, Y. et al. Lead-induced oxidative damage in rats/mice: A meta-analysis. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemb.2019.126443 (2020).

Simon, L. et al. Paternal influence of sperm DNA integrity on early embryonic development. Hum. Reprod. 29, 2402–2412 (2014).

Dolati, P. et al. Reproductive and embryological toxicity of lead acetate in male mice and their offspring and mitigation effects of quercetin. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 67, (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. The chronic effects of low lead level on the expressions of Nrf2 and Mrp1 of the testes in the rats. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 35, 109–116 (2013).

Taguchi, K. & Yamamoto, M. The KEAP1NRF2 system in cancer. Front. Oncol. 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2017.00085 (2017).

He, F., Ru, X. & Wen, T. NRF2, a transcription factor for stress response and beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134777 (2020).

Baird, L., Llères, D., Swift, S. & Dinkova-Kostova, A. T. Regulatory flexibility in the Nrf2-mediated stress response is conferred by conformational cycling of the Keap1-Nrf2 protein complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 15259–15264 (2013).

Chen, A. et al. Impaired hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis activity, spermatogenesis, and sperm function promote infertility in males with lead poisoning. Zygote 25, 103–110 (2017).

Wyck, S. et al. Oxidative stress in sperm affects the epigenetic reprogramming in early embryonic development. Epigenet. Chromatin 11, (2018).

Yamazaki, J. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of dogs with high lead exposure living near a lead mining area in Kabwe, Zambia. (2021).

Takahashi, Y. et al. Transgenerational inheritance of acquired epigenetic signatures at CpG islands in mice. Cell 186, 715-731.e19 (2023).

Silbergeld, E. K. Lead in bone: Implications for toxicology during pregnancy and lactation. Environ. Health Perspect. 91 (1991).

Rísová, V. The pathway of lead through the mother’s body to the child. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 12, 1–6 (2019).

Hu, H. et al. Fetal lead exposure at each stage of pregnancy as a predictor of infant mental development. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 1730–1735 (2006).

Satarug, S., Gobe, G. C., Vesey, D. A. & Phelps, K. R. Cadmium and lead exposure, nephrotoxicity, and mortality. Toxics vol. 8 1–42 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics8040086 (2020).

Raihan, M. J. et al. Examining the relationship between blood lead level and stunting, wasting and underweight- A cross-sectional study of children under 2 years-of-age in a Bangladeshi slum. PLoS One 13, (2018).

Gleason, K. M. Heavy metals, chronic malnutrition and neurodevelopment among children in rural BANGLADESH. (2017).

Guilarte, T. R. & Mcglothan´department Mcglothan, J. L. Hippocampal NMDA receptor MRNA undergoes subunit specific changes during developmental lead exposure. Brain Res. 790 (1998).

Blood Lead Reference Value | Lead | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/data/blood-lead-reference-value.htm (2021).

Mansouri, M. T., Naghizadeh, B., López-Larrubia, P. & Cauli, O. Behavioral deficits induced by lead exposure are accompanied by serotonergic and cholinergic alterations in the prefrontal cortex. Neurochem. Int. 62, 232–239 (2013).

He, Y. Y., Zhang, X. Y., Yung, W. H., Zhu, J. N. & Wang, J. J. Role of BDNF in central motor structures and motor diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 48, 783–793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-013-8466-y (2013).

Chan, C. B. & Ye, K. Sex differences in brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling and functions. J. Neurosci. Res. 95, 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.23863 (2017).

Sánchez-Martín, F. J., Fan, Y., Lindquist, D. M., Xia, Y. & Puga, A. Lead induces similar gene expression changes in brains of gestationally exposed adult mice and in neurons differentiated from mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS One 8, e80558- (2013).

Zhang, X.-Y., Liu, A.-P., Ruan, D.-Y. & Liu, J. Effect of Developmental Lead Exposure on the Expression of Specific NMDA Receptor Subunit MRNAs in the Hippocampus of Neonatal Rats by Digoxigenin-Labeled in Situ Hybridization Histochemistry. www.elsevier.com/locate/neutera (2002).

Myers, S. J. et al. Distinct roles of GRIN2A and GRIN2B variants in neurological conditions. F1000Research. 8. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.18949.1 (2019).

Chen, Q. et al. Differential roles of NR2A- and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in activity-dependent brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene regulation and limbic epileptogenesis. J. Neurosci. 27, 542–552 (2007).

Small, D. L. et al. Brain derived neurotrophic factor induction of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor subunit NR2A expression in cultured rat cortical neurons (1998).

Wang, R. et al. Resveratrol improved hippocampal neurogenesis following lead exposure in rats through activation of SIRT1 signaling. Environ. Toxicol. 36, 1664–1673 (2021).

Hyer, M. M., Phillips, L. L. & Neigh, G. N. Sex differences in synaptic plasticity: hormones and beyond. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11, (2018).

Schneider, J. S., Anderson, D. W., Talsania, K., Mettil, W. & Vadigepalli, R. Effects of developmental lead exposure on the hippocampal transcriptome: Influences of sex, developmental period, and lead exposure level. Toxicol. Sci. 129, 108–125 (2012).

Preston, A. R. & Eichenbaum, H. Interplay of hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in memory. Curr. Biol. 23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.041 (2013).

Norman, K. A. How hippocampus and cortex contribute to recognition memory: Revisiting the complementary learning systems model. Hippocampus 20, 1217–1227 (2010).

Schneider, J. S., Mettil, W. & Anderson, D. W. Differential effect of postnatal lead exposure on gene expression in the hippocampus and frontal cortex. J. Mol. Neurosci. 47, 76–88 (2012).

Di, K. N. & Disteche, C. M. Dosage compensation of the active X chromosome in mammals. Nat. Genet. 38, 47–53 (2006).

Saavedra-Rodríguez, L. & Feig, L. A. Chronic social instability induces anxiety and defective social interactions across generations. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 44–53 (2013).

Bishop, D. V. M. et al. Distinctive patterns of memory function in subgroups of females with turner syndrome: Evidence for imprinted loci on the X-chromosome a€ecting neurodevelopment. www.elsevier.com/locate/neuropsychologia (1999).

Davies, W., Isles, A. R., Burgoyne, P. S. & Wilkinson, L. S. X-linked imprinting: Effects on brain and behaviour. BioEssays. 28, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20341 (2006).

Mashoodh, R., Habrylo, I. B., Gudsnuk, K. M., Pelle, G. & Champagne, F. A. Maternal modulation of paternal effects on offspring development. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285, (2018).

Wells, J. C. K. Commentary: Paternal and maternal influences on offspring phenotype: The same, only different. Int. J. Epidemiol.. 43, 772–774. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu055 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JST SPRING; Grant Number JPMJSP2119, the WISE Fellowship of the Department of Science and Technology, the Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Pioneering); proposal number 20K20633 (SMMN), the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research(B); proposal number 23K28235, 23H03545 (SMMN) and Nos. 18KK0287, 21H04919, 22KK0163 (MI). The authors acknowledge financial support from the JST/JICA SATREPS (Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development; No. JPMJSA1501) and aXis (Accelerating Social Implementation for SDGs Achievement; No. JPMJAS2001) funded by JST. This study was also financed by the JST AJ-CORE Project (MI), JSPS CORE to CORE program (MI, SMMN), Hokkaido University SOUSEI-TOKUTEI Specific Research Projects (MI), JSPS Bilateral Open Partnership Joint Research Projects (JPJSBP120209902; SMMN), the Japan Prize Foundation (SMMN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; data curation; formal analysis; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing, N.B; investigation; methodology; resources; validation; visualization; writing—review and editing, N.C.S., J.Y., D.R, Y.B.Y., I.Y; investigation, data curation, resources, validation, software, N.B. and N.C.S; funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—review and editing, M.I. and S.M.M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Banda, N., Soe, N.C., Yabe, J. et al. Sex dependent intergenerational effects of lead in mouse model. Sci Rep 14, 30233 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81839-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81839-4