Abstract

In the present study, extracellular cell-free filtrate (CFF) of fungal Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum (FOC) species, was utilized to biosynthesize zinc oxide /zinc sulfide (ZnO/ZnS) nanocomposite. This was achieved by mixing the metal salt with the fungal CFF for 96 h at a temperature of 27 ± 1.0 °C and a pH of 6.5. Several analytical techniques, such as XRD, TEM, UV-Vis, FTIR, DLS, and zeta potential studies, have confirmed the synthesis of NPs. Fungal CFF enzymes and metabolites stabilized produced NPs, according to FTIR. The nanocomposite particle diameter (15–80 nm) was estimated using HR-TEM imaging. The DLS and XRD measurements verified those findings. The zone of inhibition diameter for MRSA was 35 ± 0.21 mm, while B. subtilis measured 33 ± 0.32 mm against the nanocomposite. For E. coli and S. typhi bacterial isolates, it was 25 ± 0.19 and 32 ± 0.36 mm, respectively. The determined MIC value for E. coli was 5,000 µg/mL and MRSA was 500 µg/mL. The ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite has a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect on breast cancer cells, with an IC50 of 197 ± 0.895 µg/mL. The Methylene blue dye was removed by 87.51% using the nanocomposite. Thus, green biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS nanocomposites are recommended for pharmaceutical, industrial, and biological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanoparticles (NPs) have been utilized in various fields, such as photocatalysis1, solar cells2, gas sensing3, photoluminescence materials4, and optoelectronics5. The physical, chemical, and biological techniques have all been successfully used to create a variety of nanoparticles6,7. The NPs can be synthesized via traditional physical and chemical8 processes that typically involve the utilization of hazardous substances and result in the production of waste, hence posing a risk of environmental contamination9,10. Therefore, green synthesis methods are progressively replacing physical and chemical methods due to the problems associated with the consumption of significant amounts of energy, the release of toxic and harmful chemicals, and the use of specialized equipment and synthesis conditions11. Sustainable and scalable methods for NPs production have emerged as viable alternatives, including plant, fungal, and algal-mediated synthesis12.

Zinc oxide (ZnO), zinc sulfide (ZnS), and ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite were synthesized via various techniques, including hydrothermal methods13, precipitation methods14, combustion methods15, simple thermal treatment methods16, and green synthesis employing biological treatment17. The ZnO and ZnS NPs are biosynthesized employing the usage of bioactive compounds extracted from the organisms, including plants18,19, bacteria20,21,22, fungi23,24,25, and yeast26,27,28. These microbial species are highly affecting the biological synthesis of metal and metal oxide NPs. Due to this, a growing interest in the use of microbes has been observed in the last decade, because of which several researches have been conducted using different microbiological models. On the other hand, however, the biogenesis of ZnO NPs by microorganisms is an issue that is unsolved to date29.

Fungal species, in comparison to bacteria, have a number of advantages during bioprocessing, especially when it comes to the production of gold (Au) NPs30. Fungi secrete large amounts of extracellular proteins used for various biological functions31,32. The secretome is the designation of a large group of proteins secreted into the extracellular surroundings. The homologous and heterologous proteins can be produced by highly abundant fungal secretomes. According to Kirkland et al.31 fungal hydrophobin from the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana is one of the representative protein secretion examples used in large-scale industrial applications31.

The fungi have been the primary biological agents for the production of several types of NPs. Mycosynthesis is generally applied to refer to the production of nanoparticles using fungal species, one such approach that generally comes under the umbrella of myconanotechnology. F. oxysporum is one of the most cosmopolitan species within the Kingdom of fungi due to its inclusion of plant and human pathogens. It typically infects a wide variety of species in a host-specific manner. In general, F. oxysporum has been utilized in the synthesis of various metallic silver (Ag) NPs33,34,35, Au NPs36, ZnO NPs37,38,39, and ZnS NPs40,41 using extracellularly and/or intracellularly approaches.

In intracellular synthesis, the metal precursor is introduced to the mycelial culture and then internalized within the biomass. Therefore, the extraction of NPs is necessary post-synthesis, utilizing chemical treatment, centrifugation, and filtration to disintegrate the biomass and liberate the nanoparticles42. In extracellular synthesis, the metal precursor is introduced to the aqueous filtrate containing solely fungal macromolecules, leading to the synthesis of free NPs in the filtrate solution43. This is due to the presence of primary and secondary metabolites. Therefore, the extracellular approach is the most prevalent method, as it necessitates no processes for extracting the NPs from the cells43,44,45. Also, this synthesis method is an ecologically rapidly benign process compared to physical and chemical methods. Additionally, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, although there are many literature reports on the synthesis of ZnS and ZnO NPs, this is the first report on the synthesis of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposites using F. oxysporum fungal CFF.

In this study, we report the biosynthesis and characterization of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite using fungal F. oxysporum extracellular cell-free filtrate as a reducing and stabilizing agent. The inhibitory effect of biosynthesized nanocomposite was investigated against pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, breast cancer cell cytotoxicity activity and Methylene blue dye catalytic degradation efficacy were examined against the green synthesized ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite.

Materials and methods

Materials

Zinc sulfate (ZnSO4.7H2O; 99.5%) was purchased from Merck, India. Methylene blue (MB) was purchased from Central Drug House (CDH, India). Deionized water was used throughout the experiment. The fungal strain Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cucumerinum (FOC) species was collected from a mycological laboratory at the Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, Egypt. The fungal isolate was cultured in potato dextrose agar (PDA) broth media (Merck, USA). The antimicrobial activity was evaluated via the use of four clinical bacterial isolates, Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which are Gram-positive bacteria, whereas Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Salmonella typhi (S. typhi) are Gram-negative bacteria. The other microbe was a fungal isolate of C. albicans. The antibiotics were bought from Invitrogen, USA; Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), glutamine, and sodium pyruvate from Invitrogen, U.K. MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines were obtained from the molecular biology unit, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University. Fetal calf serum (FCS), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), sodium hypochlorite solution (NaOCL, accessible chlorine 10–15%), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were given from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Every chemical used in the tests was graded as an analytical reagent.

Methods

Biosynthesis of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite by F. Oxysporum

For the biosynthesis of the NPs, F. oxysporum was cultured in 250 mL PDA broth at 25 ± 1.0 °C for 5 days under shaking conditions (180 revolutions per minute; rpm). For cell autolysis, the biomass was centrifuged at 5,000× g for 15 min (Thermo Scientific, USA), rinsed three times with sterile distilled water, and resuspended in sterile water for four days. Further, the autolysate was centrifuged at 4000× g for 5 min to obtain the cell filtration, which was subsequently filtered through sterile Whatman filter paper No. 1. The resulting liquid portion, classified as a supernatant (CFS) and a cell-free filtrate (CFF), was employed in the biosynthesis of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite.

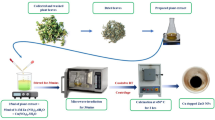

The mycosynthesis of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite involved treating the fungal extract derived from F. oxysporum with 100 mL aqueous solution of ZnSO4.7H2O (3.5 mM final concentration). In the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite synthesis process, the temperature of the mixture of CFF and ZnSO4.7H2O (1:1, v/v) was adjusted to ambient room temperature (27 ± 1.0 °C). Thereafter, the mixture was incubated at 27 ± 1.0 °C and a rotational speed of 200 rpm for 96 h in the dark (Fig. 1). Finally, the biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min (Hettich Mikro 20 Centrifuge, Germany). The sample was thoroughly rinsed three times with deionized water to eliminate impurities. After washing, these pellets underwent a 12 h cycle of oven drying at a temperature of 70 °C. The obtained pellets were finely ground into powder by using agate mortar following the drying procedure to ensure the fine dimensions of the obtained nanocomposite (Fig. 1).

Characterization of the biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite

The physicochemical properties of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite were quantified by the following methods. The UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Jenway 7205, United Kingdom) was employed to ascertain the ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectrum at room temperature over the 300–800 nm wavelength range. Deionized water was initially used as a blank reference46.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, which is based on the vibration and rotation of atoms, is a ubiquitous and extensively used spectral equipment for identifying internal molecular structures in many fields47.

A JASCO FT-IR 4100 spectrometer was used to analyze FT-IR patterns to investigate possible biomolecules present in the biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite. The samples weighing 0.2 g were mixed with potassium bromide (KBr) and subsequently compressed into discs under high pressure. In transmission mode, infrared spectra were acquired by conducting scans with a resolution of 4.0 cm− 1 across the 400–4000 cm− 1 range.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite was analyzed, using X’Pert Pro X-ray diffractometer produced (Philips Eindhoven, Netherlands). The apparatus was fitted with a proportional counter and employed nickel-filtered copper K-alpha radiation with a wavelength (λ) of 1.5405 Å. The XRD measurements were carried out at 40 kilovolts (kV) and a current of 30 milliamperes (mA). The crystalline structure of the ZnO/ZnS NPs was analyzed throughout a 2θ range extending from 10° to 80°.

The size of mycosynthesized nanocomposite in liquid solution was determined using Zetasizer nanodevices, Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern, UK, through the DLS technique. Samples were prepared by suspending nanoparticles in de-ionized water at 25 ppm. The suspension was then vortexed for homogeneity, and 1.5 ml of the solution was put into a square cuvette for subsequent measurements. Zeta potential was determined using a Zetasizer nanoarray (HT Laser, ZEN 3600; Malvern Instruments, UK).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (model JEOL TEM-2100, USA) was used in the measurement of the size and shape of nanocolloidal samples. A carbon-coated grid Type G 200, with a diameter of 3.05 prepared by48. EDX studies were conducted on Shimadzu DX-700HS equipment to identify and quantify coupled with a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) instrument (JEOL JSM 6510 lv, USA) and an energy-dispersive spectrometer detector.

Antimicrobial activity test

Antimicrobial activity

The biosynthesized F. oxysporum CFF-ZnO/ZnS -nanocomposite were tested for their antimicrobial effect against several Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as B. subtilis, MRSA, E. coli, and S. typhi, and fungal isolate C. albicansusing the well diffusion method49,50. The Petri dishes were sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min. A similar procedure was followed for the preparation and autoclaving of Luria bouillon. Afterward, L.B. agar was incorporated, and 20 mL of the agar medium was evenly spread to a depth of 4 mm. Pure pathogenic bacterial strains at 107 colony-forming units (CFU/mL) were streaked on the prepared agar plates individually using aseptic cotton swabs and left for 18 h51. Using a cork borer, wells were then created in the agar, into which suspensions of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposites were added at concentrations of 50, 100, and 150 µg/mL. To evaluate the zone of inhibition (ZIs), the Petri dishes were incubated for 24 h at 37 ± 1.0 °C. The test was conducted in triplicate, and the ZI was measured using a ruler (AIM®) and a pair of dividers then results were reported in millimeters (mm).

Minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) assay

To evaluate the MIC of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite against the tested microbes, variable concentrations of nanocomposite (50, 500, 5000, and 50,000 µg/mL) were carefully transferred into test containers. Each injected with 100 µL of a sterilized standard inoculum specifically prepared for the microbial species using L.B. broth medium49,52. The bottles, now containing the bacterial species, were incubated at 37 ± 1.0 °C for 24 h to facilitate optimal growth. For the control containers, both growth medium and inoculum were added for each microorganism examined. The bottles that displayed no turbidity compared to the control sample were utilized to determine the MIC. The MIC values indicate the concentration of the sample (in µg/mL) required to effectively inhibit microbial growth, highlighting the significant antibacterial properties of the nanocomposite.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging

SEM is an appropriate instrument for examining the microstructure and morphology of bacterial cells. To evaluate the efficacy of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite against bacterial cells that have been untreated and treated. SEM (JEOL JSM 6510 lv, USA) micrographs were conducted to examine the effect of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite against E. coli and MRSA bacterial isolates.

MTT cell cytotoxicity assay

MDA-MB-231 cells were subjected to treatment with varying concentrations of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite at 500, 250, 125, 62.5, 31.25, and 15.62 µg/mL for 24 h to evaluate cytotoxic effects. Following the treatment, 10 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was introduced to each well and incubated at 37 ± 1.0 °C for 30 min. After incubation, absorbance was measured at 540 nm with a multi-well plate reader following the addition of 100 µL of DMSO to dissolve the purple precipitate produced by formazan. The viability of the cells was evaluated by comparing the proportion of viable treated cells to that of untreated cells.

The 50% inhibitory concentration was determined via a dose-responsive curve for the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite (IC50). Based on the IC50 results, the ideal concentrations for subsequent studies were selected.

Methylene blue (MB) dye degradation

To study the MB dye degradation, MB dye powder was dissolved in deionized water to make a 1000 µg/mL stock solution39, which was the necessary amount to do this. A dilution was performed to achieve the desired concentration (50 ppm) by mixing 5 ml of a stock solution with 95 ml of distilled water39. The final solution constituted 0.01 mg of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite. The quantity of MB in the supernatant was determined at a wavelength of 664 nm utilizing a double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer, before and after adsorption and or/ degradation. To monitor the MB dye degradation, a variety of time intervals were employed, including 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min.

Statistical analysis

The data collected were evaluated using statistical analysis with a paired t-test through the IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 software package. All experimental tests were conducted in triplicate, and the results were presented as mean ± SD. The p-value was less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) giving that the difference between the groups was statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite

UV‒vis spectroscopy

The UV‒Vis absorption spectrum of the biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite was recorded (Fig. 2). It is widely recognized that ZnO NPs exhibit a prominent absorption peak at a wavelength of 350 nm, whereas the band edge of ZnS NPs is typically observed at approximately 345 nm53,54. Therefore, the absorption of a small band of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite was observed at approximately 385 nm54. However, in general, ZnO/ZnS nanocomposites display low and smooth visible light absorption due to their distinctive large energy band gap55 (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the apparent increase in absorption in the visible range can be ascribed to the light scattering phenomena exhibited by the patterned ZnO/ZnS nanoparticles55. In addition, the Gaussian absorption spectrum behavior can be attributed to the interference of light caused by the structured ZnO/ZnS NPs56. The impact of ZnS tied to the surface of ZnO on the absorption properties of ZnO in the visible light spectrum is significant57,58. Additionally, the combination of ZnS with ZnO develops a hybrid orbital within the valence band, causing a significant enhancement in the absorption of visible light. The ZnS compound contains sulfur as an anion (S2˗). Moreover, the valence band of the ZnO/ZnS complex is potentially dominated by S3p orbitals because of their comparatively higher potential energy in relation to O2p orbitals. The findings indicate that the ZnO/ZnS photocatalyst demonstrates higher photocatalytic efficiency than pure ZnO when exposed to visible light54.

XRD analysis

The XRD pattern of biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS NPs was obtained. Compared with the standard card of ZnO NPs, JCPDS: 36-1451 standards for powder diffraction. The peaks in the ZnO pattern are related to (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (112), and (201). Moreover, there are additional peaks attributed to the ZnS NPs, according to JCPDS: 05-0566, where the peaks at 29°, 47.51°, and 56.62° belong to ZnS59. Furthermore, the peaks in the JCPDS ZnO and ZnS patterns are sharper than those in the ZnO/ZnS NP pattern (Fig. 3). Moreover, in the ZnO/ZnS pattern, the strength of the ZnO-related peaks decreased, and the peaks broadened as ZnS formed60,61. The observed decrease in the peak intensity suggests that ZnS NPs might surround and/or be adjacent to the ZnO NPs. The diffraction pattern for the ZnO/ZnS nanostructure exhibited the peak that was identified, as shown in Fig. 3.

The FT-IR studies were conducted to determine the potential interactions between the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite and F. oxysporum filtrate biomolecules. These molecules play pivotal roles in the synthesis, stability, and efficient dispersion of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite within the reaction mixture. The FT-IR spectrum exhibited prominent absorption peaks at wavenumbers of 3422.24, 2926.26, 1648.80, 1411.87, 1110.8, and 622.43 cm− 1, as observed in the presence of F. oxysporum62, as shown in Fig. 4. The presence of a capping agent derived from F. oxysporum extract in the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite is evidenced by the observed wavenumbers at 3443.4, 2927.86, 2870.19, 1634.1, 1529.2, 1327.17, 1118, 629.91, and 471.5 cm− 1. Further, the spectral analysis of biogenic ZnO/ZnS nanoparticles revealed distinct peaks at wavenumbers of 3385.4, 2927.86, and 2870.19 cm− 1, corresponding to the stretching vibrations of O‒H bonds, C‒H bonds in aromatic compounds, and intramolecularly linked O‒H groups, respectively37,63. Other peaks were observed at 1634.1 cm− 1 and 1529.2 cm− 1, which correspond to the amide I band. Furthermore, two other peaks were also observed at 1327.17 cm− 1 and 1118 cm− 1, assignable to C–H bending of both aldehydes and alkanes and C–N stretching of aromatic and aliphatic amines, respectively64,65. In the present study, peaks, at 629.1 and 471.5 cm− 1 can be attributed to the formation of the Zn–O bond, as reported by66,67. The other absorption peak at 1194.1 cm− 1 was related to the presence of sulfide groups41. Therefore, biological molecules like proteins, amides, long-chain fatty acids, and polysaccharides are responsible for capping and maintaining nanoparticles of ZnO/ZnS, apart from facilitating the bioreduction of ZnO and ZnS ions37,38,41.

EDX spectroscopy analysis

The EDX measurements were performed to investigate the elemental composition of biosynthesized nanocomposite. The spectrum, displayed in Fig. 5, indicated the presence of the expected elements such as zinc (Zn), sulfur (S), and oxygen (O). Colpaert et al.68, Bakhtiari et al.69; and Tai et al.70 also reported similar elements to be present in the biosynthesized sample. In addition, a carbon peak was also detected, which might belong to the carbon residuals present in the CFF of F. oxysporum45.

TEM analysis

Figure 6(a-d) displays HR-TEM images at various magnifications in the edge region of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite. The TEM image depicts the ZnO/ZnS composite, whereby a ZnS NP is adjacent to the ZnO NP sphere71. It can be noticed that the average ZnO/ZnS nanocrystal size was between 15 and 80 nm (Fig. 6b). Distinct and regular lattice fringes are observed in the profile of the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of the ZnO/ZnS NP pattern, as shown in Fig. 6e, which is indicative of their highly crystalline nature55. Furthermore, the lattice space between the (002) and (111) lattice planes of wurtzite ZnO and cubic ZnS was found 0.25 and 0.31 nm (Fig. 6f) for ZnO and ZnS, respectively71. These findings confirm the effective deposition of ZnS NPs beside the surface of the ZnO NPs72.

Zeta potential and Zetasizer

The DLS technique was employed to assess the size distribution of the synthesized nanoparticles. The obtained findings indicate that the mean particle size diameter was found to be 77 ± 0.94 nm with a range of 30 to 110 nm (Fig. 7a). The biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS bimetallic NPs had a polydispersity index (PDI) value of 0.535, indicating that they were nearly monodisperse62. Furthermore, the zeta potential value, as shown in Fig. 7b, of the mycosynthesized nanocomposite was − 14.5 mV, indicating that the nanoparticles were nearly stable62,73.

Scheme for the biosynthesis of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite

The processes through which fungi detoxify to produce nanoparticles from sources play a role in the proposed method for generating NPs using FFEs74. Since fungi can impact detoxification processes such as the accumulation of oxygen species (ROS), they are instrumental in these procedures68,74. When a metal or its compound interacts with an organism’s system, microscopic dimensions are typically addressed in nanoscale terms75. The endoplasmic reticulum plays a role in detoxifying metal ions that enter the cytoplasm through oxidation or oxygenation processes76,77. According to Priyanka75 and Singh et al.78, sulfite reductase is responsible for converting ions (SO₄²⁻) from the environment into sulfide ions (S²⁻) as the initial step in producing ZnS NPs. Figure 8 depicts ZnS nanoparticles form when zinc metal ions in a solution react with sulfide ions chemically. This process is observed in cells and tissues in general because fungal cells exhibit increased phytochelatin production when exposed to heavy metal ions.Glutathione (γGlu-Cys-Gly) phytochelatins and metallothioneins are the substances involved in the detoxification process, within fungal cells79. Sixteen amino acids, like Phytochelate and glutathione, are known to help the body detoxify metals through metabolic processes. These substances work within the cellular cytoplasm alongside factors, like Heavy Metal Tolerance Factor 1 (HTF I) and enzymes found in cell membranes known as membrane bound monooxygenases78.

In addition, biosynthesis of ZnO NPs might prove promising with fungi owing to their extraordinary resistance to high metal concentrations, extensive binding capability, and bioaccumulation capacity. Moreover, it can extracellularly synthesize quite a significant amount of redox proteins and enzymes capable of forming NPs. The reduction of metal ions extra-cellularly is done by fungal membrane glycoproteins that can also synthesize nanoparticles. Jofillmaier et al.79 reported that more than 15 amino acids from fungi membranal glycoproteins may be responsible for the stability of biosynthesized NPS. Furthermore, the FTIR data corroborated the correlation absorption band at 1634 cm-1 to the amide II band allowing C = O stretching. This was in agreement with Mohd Yusofet al.80. On the other hand, such processes have consequences that allow a more significant quantity of metal ions to be converted into nanoparticles hence rendering them suitable for large-scale fabrication81. In addition to that, the more significant amount of protein released through the fungus into the medium served as a capping agent, which further attached to and enclosed the surface of nanoparticle, hence increasing their stability74,75.

Antimicrobial activity

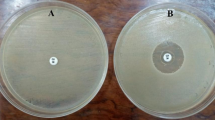

The well diffusion method was used to evaluate the antibacterial and antifungal activities of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite against pathogenic isolates of B. subtilis, MRSA, E. coli, S. typhi, and C. albicans, at different concentrations of 50, 100, and 150 µg/mL. Further, each plate was inoculated with 107 CFU of either bacterial or fungal culture (for C. albicans fungal isolate). The Amoxicillin and Vancomycin antibiotics (+ Ve control) were used for + Gram and -Gram bacterial isolates. Whereas the FFEs were conducted as -Ve control for the tested bacterial and fungal isolates (Fig. 9). Additionally, the diameters of the ZIs as shown in Fig. 9e, were expressed as mean ± SD (in mm). The results of the antibacterial activity of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite in different concentrations against the examined pathogenic B. subtilis, MRSA (Gram + Ve) isolates are illustrated in Fig. 10.

Generally, the maximum ZI diameter was estimated against both MRSA and B. subtilis bacteria (Fig. 11) at 150 µg/mL and was 35 ± 0.21 (p < 0.001) and 33 ± 0.21 ± 0.32 mm (p < 0.001), respectively. These findings were compared with those reported by Hefny et al.82; Rai et al.83. However, the maximum ZI diameters (Fig. 12) for E. coli and S. typhi, C. albicans were 25 ± 0.19, 32 ± 0.36 (p < 0.001), and 31 mm (p < 0.01), respectively62. These findings were comparable when compared to results obtained by Abdo et al.84 and Abd El-Nour et al.85.

The proposed mechanism suggests that ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite release Zn2+ ions, which can be internalized into the bacterial cell and disrupt the enzymatic system (Fig. 13). Then, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (causing the destruction of cellular components such as DNA, proteins and lipids): O2− and HO2− (do not penetrate the membrane, but direct contact causes damage) and H2O2 (internalised). Finally, internalisation within the bacteria cell and direct contact cause damage such as the loss of cellular integrity86.

Gram-negative bacteria have a thin peptidoglycan layer located between two membranes, which is recognized for giving antimicrobial resistance. Notably, dissociated carboxyl groups in the membranes provide negative charges on the cell surface. In contrast, ZnO NPs possess a positive charge, with a zeta potential of + 24 mV87. This difference creates a potent electrostatic interaction, which can disrupt the cell membrane due to the electrostatic gradient between the negatively charged membrane and the positively charged Zn²⁺ ions. As a result, both E. coli and S. typhi exhibit inhibition even at minimal concentrations of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite, showcasing the promising potential of this approach in combating serious bacterial infections86.

The quantity of tested NPs that were primarily used strongly affected the estimated inhibition zone diameter. Therefore, it is imperative to evaluate the MIC value for the biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS nanocompositeagainst each investigated pathogen. This was ascertained by detecting the lowest concentration at which bacterial growth is inhibited88,89. Various concentrations of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite ranging from 50 to 50,000 µg/mL were utilized.

These results revealed that the MIC values of ZnO/ZnS NPs for B. subtilis and MRSA were 50,000 and 500 µg/mL, respectively. On the other hand, the values of MIC for E. coli and S. typhi have been estimated to be 5,000 and 50,000 µg/mL, respectively. Thus, from the observations, it is conclusive that the bimetallic nanostructure ZnO/ZnS is more effective on both MRSA and E. coli. Thus, it is more effective against E. coli than against B. subtilis and S. typhi. Applications of ZnO/ZnS nanocompositehave efficiently inhibited growth among harmful pathogenic bacterial strains.

SEM bacterial cell imaging

SEM imaging is an appropriate technique for examining the microstructure and morphology of bacterial cells. Figure 14a–d show SEM micrographs of both treated and untreated bacterial cells. SEM analysis was used to investigate the structural alterations in the outer membrane of the untreated cells compared with treated cells with the nanocomposite. Figure 14a displays a representative SEM picture of E. coli cells (normal cells) before the incorporation of the biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite based on their antibacterial activity. It can be noticed that the surfaces of rod-like bacteria were smooth and damageless (red circles). This suggests that before treatment with nanoparticles, the cells were normal. However, post-treatment ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite exhibited surface wrinkling and a significant degree of deterioration, as illustrated in Fig. 14c. (blue circles). Therefore, it is presumptively believed that the antimicrobial effects are a result of the interactions between the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite and the bacterial cell membrane (Fig. 14d). The NPs pass through the cell and ultimately impact numerous target areas90,91. Moreover, undesirable or external chemicals can disrupt the cellular membrane, compromising its integrity and impairing the operative capacity of the barrier’s capacity to operate ultimately leading to cell death92,93,94.

MTT cell cytotoxicity assay

The MTT assay is a standard methodology employed in toxicology to elucidate the cellular response to a harmful substance and is commonly referred to as a viability assay. With regard to cell proliferation and cytotoxicity studies, the MTT assay is an extremely sensitive colorimetric technique that is utilized to evaluate the viability of cells. This was performed using the MDA-MB-231 cancer cell line95. Furthermore, Mahendiran et al.96, and Saranya et al.97 offer comprehensive insights into metabolic processes, cellular viability, and apoptosis. Figure 15 shows the correlation between the mortality rate of cancer cells and the dosage of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite, as observed at different concentrations. The results demonstrated that the IC50 value for the MDA-MB-231 cancer cell line was reported to be 197 ± 0.895 µg/mL. The findings suggested that the viability of the MDA-MB-231 cancer cell line decreased with increasing concentrations (Fig. 15) and durations of exposure to ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite. Figure 16 displays the effect of the nanocomposite on the viability of the MDA-MB-231 cells. It can be noticed that the number of cells significantly decreased with increasing the nanocomposite concentration. The capacity of the nanocomposite to form reactive oxygen species (ROS) may be the cause of this phenomena97. Since the elevated levels of ROS (Fig. 13) will severely damage cellular DNA, slowing the cell cycle and ultimately causing cell death98,99,100,101.

MB dye degradation

The catalytic degradation profile of MB dye in the dark was assessed by using the spectrophotometric analysis approach. At the beginning of UV–Vis absorbance, the detected maximum absorption peak of the MB dye was observed at λmax = 664 nm102. The dye’s absorbance readings were recorded at intervals of 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min, respectively. It can be noticed that the behavior declined as the reaction time increased up to 180 min in the presence of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite catalyst under dark conditions (Fig. 17). The detected decrease indicates a drop in the original concentration of the MB dye. The natural logarithm graph in Fig. 18 depicts the ratio of the final concentration of MB dye to its initial concentration (ln(At/A0)) as a function of time for degradation reactions facilitated by the catalysis of bioreduced ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite to the dye. The investigated reaction exhibits a correlation with pseudo-first-order kinetics, enabling the calculation of the rate constant (k) of the catalytic process using the subsequent equation:

Here, C0 and Ct denote the concentrations of MB dye before and after the catalytic reaction, respectively.

In addition, Fig. 17 displays a graph illustrating the effectiveness of bioreduced ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite catalyst in removing MB dye without light. The initial concentration of the MB dye was denoted (C0). Subsequently, the variation in the MB (Ct) concentration was quantified at certain time intervals of 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min. At the same time, the catalytic reaction solution, including MB dye and ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite, was treated to darkness. The catalytic efficiency of the ZnO/ZnS nanoparticles for the breakdown of MB dye was determined using the equation specified below:

The catalytic reduction reaction of the MB dye using ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite follows the Langmuir‒Hinshewood (LH) model103. The plots of ln(At/A0) versus time yielded good linear correlations (Fig. 17), showing that the MB dye catalyzed by the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite followed first-order kinetics. Since the rate of the equation can be written as \(\:ln\frac{{A}_{t}}{{A}_{0}}=-kt\), Where k is the rate constant of the first-order kinetics, A0 is the initial concentration of MB dye, and At is the concentration at time t. The observed values of the first-order rate constant (k) and correlation coefficient (R2) for the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite prepared via the green synthesis route were 1.0 × 10 –2 s − 1 and 0.9565, respectively. Furthermore, the concentration of MB dye achieved stability after 180 min of adsorption. This indicates that both the MB dye molecules and the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite reached a state of equilibrium between adsorption and desorption at 180 min. Consequently, 87.61% of the MB dye was eliminated during the adsorption process (Fig. 19) in the presence of the bioreduced ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite catalyst.

Furthermore, electrostatic interactions may facilitate the adsorption of positively charged MB dye molecules onto negatively charged ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite surfaces. Heger et al.104 have suggested that the MB dye’s n to π* transitions are responsible for the maximum absorption peak observed at 664 nm. Moreover, the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite catalyst markedly reduced the concentration of MB dye in an exponential manner, leading to the removal of 87.61% of the MB dye throughout the 180-minute catalysis process102. The present study suggests that the photocatalytic activity reported can be ascribed to the ZnO nanocatalyst’s tiny particle size, excellent crystallinity, and adequate bandgap energy105.

Conclusion

This work reported the novel synthesis of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite using CFF of F. oxysporum. The nanocomposite was synthesized at a room temperature of 27 ± 1.0 °C. The successful production of ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite was confirmed by characterization studies, which included UV‒Vis spectroscopy, FTIR, XRD, EDX, and TEM techniques. TEM imaging results indicated that the ZnO NPs had a nearly spherical shape with adjacent ZnS NPs layer. The dimensions of these NPs varied between 15 and 80 nm, as quantified using the DLS technique. Moreover, the FTIR analysis revealed several changes in the intensity and position of the peaks in the spectrum of the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite compared to the fungal CFF. The observed changes may be ascribed to the physical interaction between the fungal biomolecules and the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite, which functions as both a reducing and capping agent. This study evaluated the effectiveness of the nanostructures in terms of their antibacterial activity against several pathogenic bacterial isolates and their catalytic efficiency in eliminating the MB dye. Furthermore, the results indicate that the ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite displayed significant antibacterial effects against B. subtilis and MRSA bacteria, as shown by their minimum inhibitory concentration values of 50,000 and 500 µg/mL, respectively. However, the MIC values for S. typhi and E. coli have been estimated to be around 5,000 and 50,000 µg/mL, respectively. SEM images confirm the bacterial cell membrane damage according to the ROS species formation due to the NPs stress effect. Moreover, the nanocomposite demonstrated cytotoxic properties against the MDA-MB-231 cell line with the IC50 of 197 ± 0.89 µg/mL. Throughout an adsorption period of 180 min, the stability of the MB dye degradation was observed, indicating that both the MB dye molecules and the ZnO/ZnS NPs achieved a state of adsorption-desorption equilibrium. The results suggest that the biosynthesized ZnO/ZnS nanocomposite is strongly recommended for use in various biological, industrial, and biomedical application fields.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li, Y. et al. Minimalist preparation and photocatalysis properties of a spinyball-like indium-based composite suitable for different light conditions. J. Alloys Compd. 909, 164701 (2022).

Zheng, E. et al. ZnO/ZnS composites for low-temperature-processed perovskite solar cells. J. Energy Chem. 27. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2017.09.026 (2017).

Tsai, Y. S. et al. ZnO/ZnS core-shell nanostructures for hydrogen gas sensing performances. Ceram. Int. 45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.05.345 (2019).

Hitkari, G., Singh, S. & Pandey, G. Photoluminescence behavior and visible light photocatalytic activity of ZnO, ZnO/ZnS and ZnO/ZnS/ α -Fe 2 O 3 nanocomposites. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China. 28: pp. 1386–1396.DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(18)64777-6 (2018).

Sanz Marco, A., Sánchez-Tovar, R., Montes Bajo, M., Fernández-Domene, R. & García-Antón, J. Cathodoluminescence characterization of Zno/Zns nanostructures anodized under hydrodynamic conditions. Electrochim. Acta 269. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2018.03.046 (2018).

Ramos, M. et al. Silver nanoparticle from whole cells of the fungi Trichoderma spp. isolated from Brazilian Amazon. Biotechnol. Lett. 42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-020-02819-y (2020).

Sarvepalli, M., Velidandi, A. & Korrapati, N. Chemical vs biological silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, properties, and in vitro applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. p. 112667. (2024).

Khatoon, U. T. & Velidandi, A. Silver oxide nanoparticles: synthesis via chemical reduction, characterization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 159, 111690 (2024).

Ahmed, S., Ahmad, M., Swami, B. & Ikram, S. A review on plants extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications: a Green Expertise. J. Adv. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2015.02.007 (2015).

Kakakhel, M. A. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their shortcomings, animal blood a potential source for silver nanoparticles: a review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 1, 100005 (2021).

Ying, S. et al. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles: Current Developments and Limitations26p. 102336. (Environmental Technology & Innovation, 2022).

Osman, A. I. et al. Synthesis of green nanoparticles for energy, biomedical, environmental, agricultural, and food applications: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 22(2), 841–887 (2024).

Edalati, K., Shakiba, A., Khaki, J. & Zebarjad, S. Low-temperature hydrothermal synthesis of ZnO nanorods: Effect of zinc salt concentration, various solvents and alkaline mineralizers. Mater. Res. Bull. 74. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2015.11.001 (2015).

Esmaeili, F., Ghahari, M., Shafiee, M., Afarani & Soleimani-gorgani, A. Synthesis of ZnS–Mn nano-luminescent pigment for ink applications. J. Coatings Technol. 14, 1325–1332 (2018).

Reddy, A. J. et al. Structural, optical and EPR studies on ZnO:Cu Nanopowders prepared via low temperature solution combustion synthesis. J. Alloys Compd. 509(17), 5349–5355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.02.043 (2011).

Shahmirzaee, M., Shafiee Afarani, M., Nejhad, A. & Arabi, A. Microwave assisted Combustion synthesis of ZnAl 2 O 4 and ZnO nanostructure particles for Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment. Part. Sci. Technol. 37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02726351.2017.1350772 (2017).

Faisal, S. et al. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanoparticles Using Aqueous 2 Fruit Extracts of Myristica fragrans: Their Characterizations and 3 Biological and Environmental Applications. ACS Omega, XXXX. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c00310 (2021).

Villegas-Fuentes, A., Castellano, L. E., Vilchis-Nestor, A. R. & Luque, P. A. Sustainable and environmentally friendly synthesis of ZnO semiconductor nanoparticles from Bauhinia forficata leaves extract and the study of their photocatalytic and antibacterial activity. Clean. Mater. 13, 100268 (2024).

Basnet, P., Chanu, T. I., Samanta, D. & Chatterjee, S. A review on bio-synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using plant extracts as reductants and stabilizing agents. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 183, 201–221 (2018).

Kalaba, M. H., El-Sherbiny, G. M., Ewais, E. A., Darwesh, O. M. & Moghannem, S. A. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) by Streptomyces baarnensis and its active metabolite (Ka): a promising combination against multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens and cytotoxicity. BMC Microbiol. 24(1), 254 (2024).

Udayagiri, H. et al. Phytochemical fabrication of ZnO nanoparticles and their antibacterial and anti-biofilm activity. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 19714 (2024).

Saqib, S. et al. Catalytic potential of endophytes facilitates synthesis of biometallic zinc oxide nanoparticles for agricultural application. BioMetals 35(5), 967–985 (2022).

Sharma, J. L., Dhayal, V. & Sharma, R. K. White-rot fungus mediated green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and their impregnation on cellulose to develop environmental friendly antimicrobial fibers. 3 Biotech 11(6), 269 (2021).

Ali, M. B., Iftikhar, T. & Majeed, H. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles for the industrial biofortification of (Pleurotus Pulmonarius) mushrooms. Heliyon 10(19). (2024).

Mashrai, A., Khanam, H. & Aljawfi, R. N. Biological synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using C. albicans and studying their catalytic performance in the synthesis of steroidal pyrazolines. Arab. J. Chem. 10, S1530–S1536 (2017).

El-Khawaga, A. M. et al. Green synthesized ZnO nanoparticles by Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their antibacterial activity and photocatalytic degradation. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery pp. 1–12. (2023).

Boroumand Moghaddam, A. et al. Biosynthesis of ZnO nanoparticles by a new Pichia kudriavzevii yeast strain and evaluation of their antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Molecules 22(6), 872 (2017).

Chauhan, R., Reddy, A. & Abraham, J. Biosynthesis of silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles using Pichia fermentans JA2 and their antimicrobial property. Appl. Nanosci. 5, 63–71 (2015).

Mohd Yusof, H., Mohamad, R., Zaidan, U. H., Abdul, N. A. & Rahman Microbial synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and their potential application as an antimicrobial agent and a feed supplement in animal industry: a review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 10, 1–22 (2019).

Guzmán-Moreno, J. et al. Vidales-Rodríguez, fungal biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles with sporicidal activity against bacterial endospores. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 17(1), 2360489 (2024).

Kirkland, B. H. & Keyhani, N. O. Expression and purification of a functionally active class I fungal hydrophobin from the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria Bassiana in E. Coli. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 38(2), 327–335 (2011).

Seku, K., Hussaini, S. S., Reddy, M. R., Reddy, G. B. & Kumar, K. K. Fungal-mediated Synthesis of gold Nanoparticles and Their Biological Applications, in Fungal Cell Factories for Sustainable Nanomaterials Productions and Agricultural Applications. p. 23–58 (Elsevier, 2023).

Ahmad, A. et al. Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus fusarium oxysporum. Colloids Surf. B 28(4), 313–318 (2003).

Ghazala, N. H., Mohamedin, A. H., Abdel-Monem, M. O. & Elsayed, A. Antibacterial Effect of Myco-synthesized Nano-silver against Multidrug-resistant Bacteria. Egypt. J. Chem. 67(2), 587–600 (2024).

Ingle, A., Gade, A., Pierrat, S., Sonnichsen, C. & Rai, M. Mycosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus fusarium acuminatum and its activity against some human pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Nanosci. 4(2), 141–144 (2008).

Kitching, M., Ramani, M. & Marsili, E. Fungal biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles: mechanism and scale up. Microb. Biotechnol. 8(6), 904–917 (2015).

Aboelnga, A., Salaheldin, H. & Elsayed, A. Antibacterial activity using eco-friendly bio-synthesized zinc nanoparticles. Egypt. J. Chem. 67(2), 555–562. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejchem.2023.214811.8065 (2024).

Gupta, K. & Chundawat, T. S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using Fusarium oxysporum to enhance bioethanol production from rice-straw. Biomass Bioenerg. 143, 105840 (2020).

Taha, M., Elsayed, A., Abbas, M., Fakhry, H. & Ali, E. M. Bio-sorption of Methyl blue from synthetic wastewater onto copper\zinc oxides bimetallic nanoparticles synthesized by Fusarium oxysporum: equilibrium isotherms, kinetic models, process optimization, and antibacterial activity. Egypt. J. Chem. 67(2), 513–526 (2024).

Sarangi, B., Mishra, S. P. & Behera, N. Advances in green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles: an overview. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 147, 106723 (2022).

Mirzadeh, S., Darezereshki, E., Bakhtiari, F., Fazaelipoor, M. H. & Hosseini, M. R. Characterization of zinc sulfide (ZnS) nanoparticles biosynthesized by Fusarium oxysporum. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 16(2), 374–378 (2013).

Molnár, Z. et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles by thermophilic filamentous fungi. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 3943 (2018).

Li, Q., Liu, F., Li, M., Chen, C. & Gadd, G. M. Nanoparticle and nanomineral production by fungi. Fungal Biol. Rev. 41, 31–44 (2022).

Guilger-Casagrande, M. & Lima, R. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles mediated by fungi: a review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7, 287 (2019).

Loa, J., Pichardo-Molina, J., Calvo-Olvera, A., Hernández-Jiménez, M. & Rojas-Avelizapa, N. Evaluation of the culture medium in the synthesis of cadmium sulfide nanoparticles by the fungus fusarium Oxysporum. Int. J. Theoretical Appl. Nanatechnol. 10(1), 1–7 (2022).

Salaheldin, H. I., Negm, A. & Osman, G. E. Porcine skin gelatin–silver nanocomposites: synthesis, characterisation, cell cytotoxicity, and antibacterial properties. IET Nanobiotechnol. 11(8), 957–964 (2017).

Gong, Y., Chen, X. & Wu, W. Application of fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in sample preparation: material characterization and mechanism investigation. Adv. Sample Preparation 11, 100122 (2024).

Wang, Y., Wu, Y., Quadri, F., Prox, J. D. & Guo, L. Cytotoxicity of ZnO nanowire arrays on excitable cells. Nanomaterials 7(4), 80 (2017).

Ghoniem, A. A. et al. Turmeric extract-mediated biogenic synthesis of Ag@ SeO 2 magnetic nanoparticles: characterization, optimization, antibacterial and antioxidant activities. RSC Adv. 14(10), 7088–7111 (2024).

Salaheldin, H. I., Almalki, M. H. & Osman, G. E. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using bovine skin gelatin and its antibacterial effect on clinical bacterial isolates. IET Nanobiotechnol. 11(4), 420–425 (2017).

Saqib, S. et al. Bimetallic assembled silver nanoparticles impregnated in Aspergillus fumigatus extract damage the bacterial membrane surface and release cellular contents. Coatings 12, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12101505 (2022).

Mesbah, M. et al. Synthesis, characterization, spectroscopic studies and antimicrobial activity of three new Schiff bases derived from heterocyclic moiety. J. Mol. Struct. 1151, 41–48 (2018).

Mashford, B., Baldauf, J., Nguyen, T. L., Funston, A. & Mulvaney, P. Synthesis of quantum dot doped chalcogenide glasses via sol-gel processing. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 094305–094305. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3579442 (2011).

Yang, L. et al. Synthesis of ZnO/ZnS core/shell microsphere and its photocatalytic activity for methylene blue and eosin dyes degradation. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 41, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/01932691.2019.1653768 (2019).

Yang, L. et al. Synthesis of ZnO/ZnS core/shell microsphere and its photocatalytic activity for methylene blue and eosin dyes degradation. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 41(14), 2152–2158 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Design of efficient dye-sensitized solar cells with patterned ZnO–ZnS core–shell nanowire array photoanodes. Nanoscale 6. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4nr00137k (2014).

Zhang, J. et al. Effect of annealing treatment on morphologies and gas sensing properties of ZnO nanorods. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 24(3), 736–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(14)63119-8 (2014). .DOI.

Biroju, R., Narayanan, T. & Vineesh, T. V. New advances in 2D electrochemistry—Catalysis and Sensing. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315152042-7 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Novel porous single-crystalline ZnO nanosheets fabricated by annealing ZnS(en) 0.5 (en = ethylenediamine) precursor. Application in a gas sensor for indoor air contaminant detection. Nanotechnology 20, 125501. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/20/12/125501 (2009).

Serrà, A. & Philippe, L. Simple and scalable fabrication of hairy ZnO@ZnS core@shell Cu cables for continuous sunlight-driven photocatalytic water remediation. Chem. Eng. J. 401, 126164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.126164 (2020).

Poliukhova, V. et al. ZnS/ZnO nanosheets obtained by thermal treatment of ZnS/ethylenediamine as a Z-scheme photocatalyst for H2 generation and cr(VI) reduction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 575, 151773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.151773 (2021).

Rai, M. et al. Fusarium as a Novel Fungus for the synthesis of nanoparticles: mechanism and applications. J. Fungi 7, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7020139 (2021).

Mohamed, A., Abu-Elghait, M., Ahmed, N., Salah, S. & Salem Eco-friendly Mycogenic Synthesis of ZnO and CuO Nanoparticles for In Vitro Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, and Antifungal Applications. Biological Trace Element Research, 199. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-020-02369-4 (2021).

Mohamed, A. A. et al. Fungal strain impacts the shape, bioactivity and multifunctional properties of green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 19, 101103 (2019).

Trzcińska-Wencel, J., Wypij, M., Terzyk, A. P., Rai, M. & Golińska, P. Biofabrication of novel silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles from Fusarium solani IOR 825 and their potential application in agriculture as biocontrol agents of phytopathogens, and seed germination and seedling growth promoters. Front. Chem. 11, 1235437 (2023).

Fouda, A., Saad, E., Salem, S. S. & Shaheen, T. I. In-Vitro cytotoxicity, antibacterial, and UV protection properties of the biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles for medical textile applications. Microb. Pathog. 125, 252–261 (2018).

Mohamed, A. A., Abu-Elghait, M., Ahmed, N. E. & Salem, S. S. Eco-friendly mycogenic synthesis of ZnO and CuO nanoparticles for in vitro antibacterial, antibiofilm, and antifungal applications. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 199(7), 2788–2799 (2021).

Colpaert, J. V., Wevers, J. H., Krznaric, E. & Adriaensen, K. How metal-tolerant ecotypes of ectomycorrhizal fungi protect plants from heavy metal pollution. Ann. For. Sci. 68, 17–24 (2011).

Bakhtiari, S. & Abdoos, H. Karimzadeh Green synthesis of ZnO@ZnS core–shell nanoparticles for detection of lead and iron ions in aqueous solutions by colorimetric paper sensors. Chem. Pap. 76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11696-021-01840-3 (2021).

Tai, S. T., Tsai, Y. S., Wu, Y. S., Wang, J. J. & Chen, H. Material characterizations of ZnO/ZnS core-shell structures on glass substrate. Results Phys. 15, 102703 (2019).

Ma, H. et al. Synthesis of visible light responsive ZnO–ZnS/C photocatalyst by simple carbothermal reduction. Appl. Catal. B 102(3–4), 417–423 (2011).

Kumari, P., Pande, S. & Fageria, P. Facile synthesis of ZnO/ZnS hollow nanorods via Kirkendall effect with enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30(22), 61927–61944 (2023).

Bahmani, B., Moztarzadeh, F. & Rabiee, M. Synthesis zinc Sulfide Semicond. Nanopart. Coprecipitation Method Biol. Diagnostics 9. (2007).

Adeleke, B. S. et al. Biosynthesis of Nanoparticles Using Microorganisms: A Focus on Endophytic Fungi. Heliyon, (2024).

Priyanka, U. Biosynthesis of Zinc Sulphide (ZnS) Nanoparticles from Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus Flavus for Degradation of Organic Pollutants. (National Institute of Technology Karnataka, 2019).

Ballottin, D. et al. Elucidating protein involvement in the stabilization of the biogenic silver nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 11, 1–9 (2016).

Jha, A. K. & Prasad, K. Biological synthesis of cobalt ferrite nanoparticles. Nanatechnol. Dev. 2(1), e9–e9 (2012).

Singh, P., Kim, Y. J., Zhang, D. & Yang, D. C. Biological synthesis of nanoparticles from plants and microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 34(7), 588–599 (2016).

Schoffelmeer, E. A. M., Klis, F. M., Sietsma, J. & Cornelissen, B. J. The cell wall of Fusarium oxysporum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 27(2–3), 275–282 (1999).

Mohd Yusof, H., Abdul Rahman, N. A., Mohamad, R., Zaidan, U. H. & Samsudin, A. A. Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles by cell-biomass and supernatant of Lactobacillus plantarum TA4 and its antibacterial and biocompatibility properties. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 19996 (2020).

Gaber, S. E., Hashem, A. H., El-Sayyad, G. S. & Attia, M. S. Antifungal activity of myco-synthesized bimetallic ZnO-CuO nanoparticles against fungal plant pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04550-w (2023).

Hefny, M. E., El-Zamek, F. I., El-Fattah, A. & Mahgoub, S. Biosynthesis of zinc nanoparticles using culture filtrates of aspergillus, Fusarium and Penicillium fungal species and their antibacterial properties against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Zagazig J. Agricultural Res. 46(6), 2009–2021 (2019).

Rai, M. et al. Biogenic silver nanoparticles: what we know and what do we need to know? Nanomaterials 11(11), 2901 (2021).

Abdo, A. M. et al. Green synthesis of Zinc Oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their activity against pathogenic microbes and common house mosquito, Culex pipiens. Materials 14(22), 6983 (2021).

El-Nour, A., Amira, T., Abou-Dobara, M. I., El-Sayed, A. K. & El-Zahed, M. M. Extracellular biosynthesis and antimicrobial activity of Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 zinc oxide nanoparticles. Sci. J. Damietta Fac. Sci. 12(2), 39–47 (2023).

Lallo da Silva, B. et al. Relationship between structure and antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles: an overview. Int. J. Nanomed. pp. 9395–9410. (2019).

Anitha, R., Ramesh, K., Ravishankar, T., Kumar, K. S. & Ramakrishnappa, T. Cytotoxicity, antibacterial and antifungal activities of ZnO nanoparticles prepared by the Artocarpus gomezianus fruit mediated facile green combustion method. J. Science: Adv. Mater. Devices 3(4), 440–451 (2018).

Hassan, S. et al. New approach for antimicrobial activity and bio-control of various pathogens by biosynthesized copper nanoparticles using endophytic actinomycetes. J. Radiation Res. Appl. Sci. 11. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrras.2018.05.003 (2018).

Fouda, A., Hassan, S., Salah Salem, S. & Shaheen, T. In-Vitro cytotoxicity, antibacterial, and UV protection properties of the biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles for medical textile applications. Microb. Pathog. 125. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2018.09.030 (2018).

Kang, S. G., Lee, K. & Vinayagam, R. Salicylic-zinc nanocomposites with enhanced antibacterial activity. Coatings 13, 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings13050941 (2023).

Ahmed, B. et al. Destruction of Cell Topography, morphology, membrane, inhibition of respiration, Biofilm formation, and Bioactive Molecule production by nanoparticles of Ag, ZnO, CuO, TiO(2), and Al(2)O(3) toward beneficial soil Bacteria. ACS Omega. 5(14), 7861–7876. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b04084 (2020).

Gudkov, S. et al. A Mini Review of Antibacterial properties of ZnO nanoparticles. Front. Phys. 9, 641481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2021.641481 (2021).

Karnwal, A. et al. Perspectives on usage of functional nanomaterials in Antimicrobial Therapy for antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. ACS Omega 8(15), 13492–13508. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c00110 (2023).

Monte, J., Abreu, A., Borges, A., Simões, L. & Simões, M. Antimicrobial activity of selected phytochemicals against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus and their Biofilms. Pathogens 3, 473–498. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens3020473 (2014).

Ghasemi, M., Turnbull, T., Sebastian, S. & Kempson, I. The MTT assay: utility, limitations, pitfalls, and interpretation in bulk and single-cell analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(23), 12827 (2021).

Mahendiran, D. et al. Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using plant extracts of Aloe vera and Hibiscus sabdariffa: phytochemical, antibacterial, antioxidant and anti-proliferative studies. BioNanoScience 7(3), 530–545 (2017).

Saranya, S., Vijayaranai, K., Pavithra, S., Raihana, N. & Kumanan, K. Vitro cytotoxicity of zinc oxide, iron oxide and copper nanopowders prepared by green synthesis. Toxicol. Rep. 4, 427–430 (2017).

Wang, Y., Wu, Y., Quadri, F., Prox, J. & Guo, L. Cytotoxicity of ZnO nanowire arrays on excitable cells. Nanomaterials 7, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano7040080 (2017).

Mir, D. et al. Antimicrobial and biocompatibility of highly fluorescent ZnSe core and ZnSe@ZnS core-shell quantum dots. J. Nanopart. Res. 20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-018-4281-8 (2018).

Saranya, S., K, V., Kathaperumal, K. & P. S, R. N, and Vitro cytotoxicity of zinc oxide, iron oxide and copper nanopowders prepared by green synthesis. Toxicol. Rep. 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2017.07.005 (2017).

Kim, D. Y. et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles exhibit both cyclooxygenase- and lipoxygenase-mediated apoptosis in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Toxicol. Res. 35(1), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.5487/tr.2019.35.1.083 (2019).

Negash, A., Mohammed, S., Weldekirstos, H. D., Ambaye, A. D. & Gashu, M. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye using eco-friendly synthesized rGO@ ZnO nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 22234 (2023).

Salaheldin, H. I. N. Comparative catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol by polyacrylamide-gold nanocomposite synthesized by hydrothermal autoclaving and conventional heating routes. Adv. Nat. Sciences: Nanosci. 8(4), 045001 (2017).

Heger, D., Jirkovsky, J. & Klan, P. Aggregation of methylene blue in frozen aqueous solutions studied by absorption spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A. 109(30), 6702–6709 (2005).

Zhang, Z. et al. Facile one-step synthesis of TiO2/Ag/SnO2 ternary heterostructures with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 10532 (2018).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MRs/ Aboelnga performed all the antimicrobial activity experiments. Prof. Salaheldin, Prof. Elsayed, and MRs/ Aboelnga analyzed the results. Prof. Salaheldin and MRs/ Aboelnga prepared the study figures. Prof. Salaheldin and Prof. Elsayed carried out the final draft and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salaheldin, H., Aboelnga, A. & Elsayed, A. Mycosynthesis of zinc sulfide/zinc oxide nanocomposite using Fusarium oxysporum for catalytic degradation of methylene blue dye, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities. Sci Rep 14, 32165 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81855-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81855-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Harnessing wasted mushroom peel aqueous extract for mycogenic synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles for solar photocatalysis and antimicrobial applications

Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery (2025)