Abstract

Periodontitis is closely related to lifestyle habits. Our objective was to examine the relationship between the Life’s Essential 8 (LE8) and the prevalence of periodontitis in American adults. This study used data from the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). LE8 scores (range 0–100) were measured according to the definition by the American Heart Association (AHA) and were categorized as low (0–49), medium (50–79), and high (80–100). The NHANES database on periodontal health was used to data to determine the prevalence of periodontitis. Multivariate regression models and restricted cubic spline (RCS) models were used to assess correlations. Weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression was used to explore the association of LE8 and its components with periodontitis risk. Stratified analysis and interaction analysis were conducted to assess the consistency of the results. In addition, mediation analyses were performed to investigate the role of systemic inflammation in mediating the association of LE8 with periodontitis risk. Participants with moderate (LE8 score 50–79) and high (LE8 score 80–100) scores had 58% (95% CI 0.43–0.79, P < 0.001) and 55% (95% CI 0.37–0.84, P = 0.010) less periodontitis prevalence, respectively, compared with adults with lower total scores. Among all 8 indicators, nicotine exposure (62.3%), blood glucose (18.2%), sleep heath (8.2%), and blood pressure (7.7%) had the most significant impact on periodontitis. Notably, no statistically significant interactions were observed in all subgroup analyses except age (P for interaction < 0.05), indicating that the protective effect of LE8 on periodontitis was shown to be more pronounced in individuals between 40 and 60 years of age. In addition, neutrophil, white blood cell (WBC), and albumin levels mediated the association between LE8 and periodontitis risk, mediating proportions of 13.3%, 21.4%, and 8.3%, respectively. These findings suggest that poorer LE8 scores increase the risk of periodontitis, which may be partly mediated by systemic inflammation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Periodontitis is a common chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the destruction of tooth-supporting tissues, which can lead to tooth loss if left untreated1. It affects approximately 50% of adults aged 30 years or older2. Periodontitis has been associated with increased risks of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and mortality3,4. Therefore, identifying modifiable risk factors for periodontitis may provide an opportunity to prevent this disease and its adverse outcomes.

Recently, the American Heart Association (AHA) proposed a new cardiovascular health (CVH) metric, Life’s Essential 8 (LE8), which comprises four health behaviors (diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, and sleep) and four health factors (body mass index [BMI], cholesterol, blood glucose, blood pressure)5. Better CVH, as measured by LE8, has been associated with lower risks of incident ASCVD, cancer, and all-cause mortality6,7,8. However, there are few studies exploring the relationship between LE8 and the risk of periodontitis. In addition, systemic inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of both ASCVD and periodontitis9,10. Yet, whether inflammation mediates the association between LE8 and periodontitis is unknown.

Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to investigate the association of LE8 with periodontitis prevalence using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). We also examined the potential mediating role of circulating inflammatory markers, including white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil count, albumin, and C-reactive protein (CRP) in this association.

Methods

Study design and participants

The data used in this study were obtained from NHANES 2009–2014, a periodic cross-sectional health survey program that has been collecting nationally representative samples of the U.S. ambulatory population on a 2-year cycle since 1999, using a stratified, multistage, and probability cluster design11. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) administered the survey. The study protocols adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki and the NCHS institutional ethics review board approved it. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from all participants. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines12.

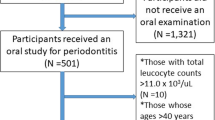

Of the 30,468 participants in NHANES 2009–2014, we excluded 19,754 participants who could not definitively diagnose the presence of periodontitis, 2554 who could not calculate LE8 scores, and 940 who were missing information on covariates. Ultimately, a total of 7220 participants aged greater than or equal to 20 years were enrolled in this study (males: 3594, females: 3626), as shown in the flowchart Fig. 1.

Measurement of LE8

The LE8 score consists of four health behaviors (diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, and sleep duration) and four health factors (BMI, cholesterol, blood glucose, and blood pressure). Detailed algorithms for calculating LE8 scores for each of the metrics in the NHANES data have been previously published5,13. The scores for the eight LE8 metrics range from 0 to 100. The overall LE8 score was calculated from the arithmetic mean of the eight metrics. Participants with scores between 80 and 100 were defined as high LE8, 50–79 as moderate LE8, and 0–49 as low LE85.

Dietary indicators were assessed using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) 201514. The HEI-2015 score was constructed and calculated by combining participants’ dietary intake collected through two 24-h dietary reviews with food pattern equivalent data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)15. Physical activity, smoking, sleep duration, history of diabetes, and medication history were collected using a self-report questionnaire; blood pressure, height, and weight information were obtained from physical examination data. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Information on blood lipids, blood glucose, WBC count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, CRP and albumin was obtained from laboratory data.

Measurements and definition of periodontitis

Periodontitis data were derived from Oral Health-Periodontal in Examination data in NHANES 2009–2014. Data related to periodontal examinations were collected completely within this time frame. These periodontal oral health data will be used to assess the prevalence of major oral diseases, including dental caries, periodontal disease, and dental fluorosis. Survey participants were eligible for periodontal evaluation if they had at least one tooth (excluding the third molar) and did not meet any health exclusion criteria (Have received a heart transplant, artificial heart valve, congenital heart disease, or bacterial endocarditis). All clinical examiners were thoroughly trained and calibrated by the reference examiner for the survey. In our study, we utilized two clinical metrics: Clinical Attachment Loss (CAL) and Probing Depth (PD). The diagnostic criteria for periodontitis was based on case definitions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Periodontology (CDC/AAP): Severe periodontitis is identified by interproximal areas with a CAL of ≥ 6 mm and at least one interproximal area with a PD of ≥ 5 mm, not on the same tooth. Moderate periodontitis is defined by two or more interproximal sites with a probing pocket depth of ≥ 5 mm or a clinical attachment level of ≥ 4 mm, not on the same tooth16. Moderate/severe periodontitis cases were identified as patients with periodontitis, while all other cases were classified as the reference group.

Covariates assessment

Demographic characteristics were obtained from the household interview questionnaires, and for this study, gender (male, female), age (categorized into three groups: 20–40 years old, 40–60 years old, and 60–80 years old), race (categorized into five groups: Mexican American, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, other Hispanic, and other races), education level (categorized into three groups: less than high school, high school, college or above), poverty ratio (categorized into three groups: < 1 for low income, 1–3 for middle income and > 3.5 for high income), and alcohol use (categorized into five groups: ever drinker, heavy drinker, moderate drinker, light drinker, and never drinker) were used as covariates.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics of subjects under periodontal status were assessed using chi-square tests and t-tests. Multivariate linear regression was used to explore the association of LE8 and inflammatory markers with periodontitis, and restricted cubic spline (RCS) was used to analyze the dose-dependent relationship between LE8 and periodontitis risk. Stratified analysis and interaction analysis were primarily based on age, gender, race, education level, and poverty ratio. Covariates adjusted for in all analyses were sex, race, education level, poverty ratio, and alcohol use. Missing data for covariates were coded as missing indicator categories for categorical variables and estimated using the median of continuous variables. Weighted Quantile Sum (WQS) regression was used to explore the overall effect of LE8 on periodontitis (R package “gWQS”), which allows for the empirical calculation of a WQS index consisting of a weighted sum of the individual LE8 indicators, as well as identifying the magnitude of the effect of the different LE8 indicators on periodontitis through the weighted sum.

WBC count, neutrophil count, CRP, and albumin level results were categorized into four quartiles (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4) as categorical variables. The potential mediating effect of inflammatory markers on the association between LE8 and periodontitis risk was estimated by parallel mediation analysis (R package “mediation”). Direct effect (DE) indicates the effect of inflammatory markers on periodontitis without mediators. Indirect effect (IE) shows the effect of inflammatory markers on periodontitis via mediators. The mediator proportion was calculated by dividing the IE by the total effect (TE). Statistical tests were two-sided, with P < 0.05 defined as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4) and R (version 3.6.3).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 7220 participants were included in this study, and the baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1 by the presence or absence of periodontitis status. There were a total of 3594 males and 3626 females. Compared with non-periodontitis participants, periodontitis participants were older, less educated, and had relatively lower household income. Non-periodontitis participants had higher LE8 scores, whereas BMI, lipid, and diet scores did not differ significantly between the two groups. In addition, participants with periodontitis had higher leukocyte and neutrophil levels and relatively lower albumin levels.

Associations of LE8 with periodontitis risk

After multivariate adjustment, compared with low LE8, the adjusted odd ratio (OR) for periodontitis patients in the moderate LE8 group was 0.58 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.43–0.79, P < 0.001) and for periodontitis patients in the high LE8 group was 0.55 (95% CI 0.37–0.84, P = 0.010) (Table 2).

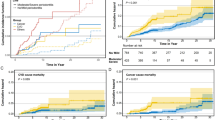

Univariate RCS analysis showed a nonlinear association between LE8 scores and periodontitis (P for nonlinear = 0.003). The minimum threshold for a beneficial association was between 60 and 70 points (estimate OR = 1). In contrast, in the multivariate corrected RCS analysis, there was a linear association between LE8 score and periodontitis (P for linear = 0.301) (As shown in Fig. 2).

Dose–response relationships between Life’s Essential 8 scores and periodontitis. (a) Unadjusted; (b) adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, education attainment, poverty income ratio and alcohol drinker. ORs (solid lines) and 95% confidence levels (dotted lines). OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, LE8 Life’s Essential 8.

In order to assess the reliability of the results and to look for potential influencing factors, we performed stratified analysis and interaction analysis by age, gender, race, education, and poverty ratio subgroups, which showed that no statistically significant interactions were observed in all subgroups of the analysis, except for age ( P < 0.05 for interaction), and that from the data, it was clear that the protective effect of LE8 against periodontitis was more pronounced in the more pronounced in the age group of 40 to 60 years (Fig. 3).

Association between Life’s Essential 8 and periodontitis by age, gender, race, education level, and poverty ratio. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, eth ethnicity, Edu education age (1 = 20–40 years old, 2 = 40–60 years old, 3 = 60–80 years old), education (0 = less than high school, 1 = high school, 2 = college or above), poverty ratio (1 = low income, 2 = middle income,3 = high income).

Association between components of the LE8 and periodontitis risk

The association between LE8 and periodontitis was analyzed by WQS regression, and the LE8 score was negatively associated with the risk of developing periodontitis (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.36–0.55, P < 0.001). In addition, as shown in Fig. 4, among the indicators that comprise the LE8, the highest weighted factors were nicotine exposure (62.3%), blood glucose (28.2%), sleep heath (8.2%), and blood pressure (7.7%), respectively.

Weighted values of Life’s Essential 8 components for periodontitis in WQS models. Models were adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, education attainment, poverty income ratio and alcohol drinker. bp blood pressure, hei Healthy Eating Index, non.hdl Non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol, pa physical activity.

Associations of systemic inflammation with periodontitis

The association between inflammatory markers and the risk of periodontitis was further explored. The results are shown in Table 3, where leukocytes (Q4 vs. Q1: OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.26- 1.94, P < 0.001) and elevated neutrophils (Q4 vs. Q1: OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.33–2.16, P < 0.001) were all associated with an increased risk of periodontitis, while high albumin (Q4 vs. Q1: OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.52–0.94, P = 0.020) were associated with a decreased risk of periodontitis.

Mediation analyses

In addition, a parallel mediation analysis of inflammatory markers was performed to assess the potential mediating effect of systemic inflammation on the association of LE8 with periodontitis risk. Some inflammatory markers such as neutrophils, leukocytes, and albumin significantly mediated the association of LE8 with periodontitis risk (P < 0.05). The proportions were 13.3%, 21.4%, and8.3%, respectively (Fig. 5). Notably, CRP did not play a role in this association (P > 0.05).

Estimated proportion of the association between LE8 and periodontitis mediated by neutrophils (a), WBC (b), and albumin(c). Models were adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, education attainment, poverty income ratio and alcohol drinker. CI confidence interval, LE8 Life’s Essential 8, WBC white blood cell.

Discussion

In this nationally representative cross-sectional study, we found that higher LE8 scores was associated with a lower prevalence of periodontitis. Participants with moderate (50–79) and high (80–100) LE8 scores had 58% and 55% lower odds of periodontitis, respectively, compared with participants with lower (0–49) LE8 scores, after adjusting for potential confounders. Among the LE8 components, nicotine exposure, blood glucose, sleep heath, and blood pressure significantly impacted periodontitis. In addition, systemic inflammation, as evidenced by levels of neutrophils, white blood cells, and albumin, emerged as a mediator linking LE8 to periodontitis. To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies to demonstrate study demonstrating an inverse association between the AHA’s new cardiovascular health metric LE8 and periodontitis in US adults.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies showing that ideal cardiovascular health is associated with lower risks of periodontitis17,18. Several potential mechanisms may explain the observed association between better cardiovascular health and lower periodontitis prevalence. First, cardiovascular diseases and periodontitis share common risk factors, such as smoking19, diabetes20, and physical inactivity21. Second, chronic inflammation plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of both atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease9 and periodontitis10. Third, our mediation analysis provided evidence supporting systemic inflammation as an intermediate pathway linking cardiovascular health to periodontitis.

Our findings show that the higher the LE8 score, the lower the prevalence of periodontitis. Our results align with the evidence linking LE8 to lower incidences of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and all-cause mortality6,7,22. The observed inverse association between LE8 and periodontitis prevalence also corroborates prior research indicating the detrimental impacts of unfavorable lifestyle factors such as smoking, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes on periodontal health19,23,24,25.

Furthermore, the mediating role of systemic inflammation found in our study is consistent with the current understanding of the pathogenesis of both cardiovascular disease and periodontitis9,10,26. Several potential biological mechanisms may explain the observed inverse association between cardiovascular health and periodontitis. First, chronic inflammation plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of both cardiovascular disease and periodontitis26,27. Elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers have been linked to increased risks of atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction and stroke28. Meanwhile, the inflammatory response induced by periodontal bacteria is recognized as the primary pathway leading to the destruction of periodontal tissues. Our study provides novel evidence that systemic inflammation may be a common pathway through which cardiovascular health influences periodontitis. However, in our analysis, we found that CRP did not mediate the relationship between LE8 and periodontitis. The data for CRP were significantly missing from the NHANES database, therefore, we believe that the representativeness and statistical validity of the study results may be reduced due to objective factors such as missing data. Meanwhile, due to uncontrollable factors such as missing data and sample representativeness issues, we were not able to include fibrinogen, interleukins, and TNF- α, which are more representative of systemic inflammation, and therefore the results may not fully reflect the role of inflammation in periodontal disease. To elucidate the intricate interactions between cardiovascular health, inflammation, and periodontitis, it is necessary to consider and discuss these important biomarkers more comprehensively in future studies in order to provide more complete and accurate results.

Second, metabolic disorders like diabetes can increase susceptibility to periodontitis29,30. Hyperglycemia impairs neutrophil function and collagen synthesis, resulting in more severe periodontal breakdown31. The glycemic control component in LE8 is associated with diabetes risk, which may subsequently influence periodontitis risk.

Third, smoking is a major modifiable risk factor for both cardiovascular disease and periodontitis32. Tobacco smoke induces systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, which can exacerbate both atherosclerosis and periodontal tissue destruction. The nicotine exposure metric in LE8 captures the adverse impacts of smoking on oral and cardiovascular health. Tobacco/nicotine exposure was confirmed as a strong predictor of periodontitis in the WQS index-related results, which not only validates existing research findings but also emphasizes the importance of controlling tobacco exposure in health management and prevention strategies.

In contrast, BMI and physical activity were given less weight in the WQS index correlation results. We consider the possibility that on the one hand, our sample, which contained a larger number of individuals with normal or near-normal BMI, had relatively little variability and thus lacked sufficient differences to affect the predictive power of the model significantly. In addition, BMI and physical activity are influenced by other factors, which may also result in their effect on periodontitis being masked by other, more direct risk factors. The mechanisms by which BMI and physical activity influence periodontitis are more complex, and it is possible that these factors may have a greater influence on the overall assessment of health, thus reducing their independent contribution.

In summary, the potential mechanisms linking LE8 to periodontitis appear to be multifactorial, involving shared risk factors, chronic inflammation, metabolic disorders, and unhealthy lifestyles like smoking. Further research is needed to elucidate the complex interactions better.

Our study has several notable strengths. First, few previous studies have explored the relationship between LE8 and periodontitis, our study adds novel evidence to the literature. Second, our analysis was based on a large nationally representative sample of US adults, enhancing the external validity and generalizability of the findings. Third, using the LE8 provides a comprehensive assessment of lifestyle habits by combining smoking, body mass index, diet, physical activity, cholesterol, blood glucose, and blood pressure. Not only does it focus on the direct impact of individual risk factors on periodontal disease, but it also examines the potential interactions between these factors. This integrated perspective provides a more comprehensive assessment of health status than a single risk factor analysis, and a more precise identification of high-risk populations, thus providing an important basis for early intervention and prevention. As a result, risk estimates are more reliable than in previous studies of individual factors. The LE8 Index, a comprehensive health assessment tool, highlights the potential effectiveness of reducing the incidence of periodontal disease through overall health behavior improvement. This provides a new way of thinking about public health strategies, whereby broader health gains can be realized by promoting a holistic healthy lifestyle, rather than just controlling individual risk factors.

However, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature precludes causal inference, and the possibility of reverse causation cannot be ruled out. Prospective cohort studies are warranted to determine the temporal sequence between LE8 and periodontitis. Second, LE8 scores were calculated primarily based on self-reported data, possibly subject to recall bias. Future research should include more objective measurements, such as accelerometers for physical activity. In addition, some indicators that are more responsive to systemic inflammation could not be included in the analysis due to uncontrollable factors such as missing data. Nevertheless, our study provides novel and valuable insights into the relationship between ideal lifestyle habits and lower periodontitis prevalence in US adults. Further intervention studies are needed to verify whether improving lifestyle habits reduces the risk of periodontitis.

The study provides evidence that improving lifestyle habits may confer benefits in preventing periodontitis. Periodontitis is a highly prevalent chronic inflammatory disease that affects nearly half of US adults2. Our results suggest that promoting cardiovascular health through lifestyle changes and risk factor control could be a promising population-based strategy to curb the rising burden of periodontitis. The LE8 score provides a framework for integrated health management that can help clinicians comprehensively assess a patient’s overall health status, contributing to the development of more holistic prevention and treatment strategies as well as individualized interventions to improve a patient’s overall health. At the same time, through early identification and management of multiple health risk factors, the LE8 can help reduce the incidence of periodontitis and the healthcare burden and costs associated with it.

The association between better lifestyle habits and lower periodontitis prevalence warrants further investigation in prospective cohort studies to determine causal relationships and temporal sequence33. Future research should also explore whether incorporating periodontal disease prevention and treatment into CVH management programs can improve oral and systemic health outcomes. Community-based interventions targeting shared modifiable risk factors may be a practical approach to managing both cardiovascular disease and periodontitis34.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this nationally representative study of US adults found that better lifestyle habits, as measured by AHA’s LE8 metric, was associated with a lower prevalence of periodontitis. After adjusting for potential confounders, participants with moderate and high LE8 scores had over 50% lower odds of having periodontitis than those with poor LE8 scores. Systemic inflammation appeared to mediate the linkage between LE8 and periodontitis. To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies to demonstrate study demonstrating an inverse association between LE8 and periodontitis in US adults.

Our findings highlight the interconnectedness between oral and systemic health. Fostering lifestyle habits through improving diet, increasing physical activity, avoiding tobacco, and better managing blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose levels may profoundly impact periodontitis risks. Further prospective cohort studies are warranted to confirm the causal relationship and underlying mechanisms. Collaborative efforts between dental and healthcare providers are needed to promote joint management of oral and lifestyle habits. Population-based strategies that target shared modifiable risk factors may provide innovative approaches to curb the growing burden of periodontitis and its related systemic consequences.

Data availability

Specific information can login web site: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes. Anyone who meets the requirements for database usage can access the database.

Abbreviations

- ASCVD:

-

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- AHA:

-

American Heart Association

- AL:

-

Attachment loss

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CVH:

-

Cardiovascular health

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DE:

-

Direct effect

- HEI:

-

Healthy Eating Index

- IE:

-

Indirect effect

- LE8:

-

Life’s Essential 8

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- OR:

-

Odd ratio

- PD:

-

Pocket depth

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- TE:

-

Total effect

- USDA:

-

United States Department of Agriculture

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- WQS:

-

Weighted quantile sum

References

Pihlstrom, B. L., Michalowicz, B. S. & Johnson, N. W. Periodontal diseases. The Lancet 366, 1809–1820 (2005).

Eke, P. I. et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J. Periodontol. 86, 611–622 (2015).

Teeuw, W. J. et al. Treatment of periodontitis improves the atherosclerotic profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 41, 70–79 (2013).

Linden, G. J., Lyons, A. & Scannapieco, F. A. Periodontal systemic associations: Review of the evidence. J. Periodontol. 84, 1340010 (2013).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Life’s Essential 8: Updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 146, 1078 (2022).

Liu, K. et al. Healthy lifestyle through young adulthood and the presence of low cardiovascular disease risk profile in middle age. Circulation 125, 996–1004 (2012).

Reis, J. P. et al. Cardiovascular health through young adulthood and cognitive functioning in midlife. Ann. Neurol. 73, 170–179 (2013).

Reis, J. P. et al. Association between duration of overall and abdominal obesity beginning in young adulthood and coronary artery calcification in middle age. Jama 310, 280 (2013).

Epstein, S. E. et al. Infection and atherosclerosis potential roles of pathogen burden and molecular mimicry. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 1417–1420 (2000).

Loos, B. G. Systemic markers of inflammation in periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 76, 2106–2115 (2005).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. National center for health Statistics. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Elm, E. V. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457 (2007).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Status of cardiovascular health in US adults and children using the American Heart Association’s New “Life’s Essential 8” Metrics: Prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2013 through 2018. Circulation 146, 822–835 (2022).

Krebs-Smith, S. M. et al. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 118, 1591–1602 (2018).

Vilar-Gomez, E. et al. High-quality diet, physical activity, and college education are associated with low risk of NAFLD among the US population. Hepatology 75, 1491–1506 (2022).

Eke, P. I., Borgnakke, W. S. & Genco, R. J. Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontology 2000, 257–267 (2020).

Carra, M. C., Rangé, H., Caligiuri, G., & Bouchard, P. Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A critical appraisal. Periodontology 2000 (2023).

Priyamvara, A. et al. Periodontal inflammation and the risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 22, 6 (2020).

Tomar, S. L. & Asma, S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: findings from NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Periodontol. 71, 743–751 (2000).

Lalla, E. et al. Diabetes mellitus promotes periodontal destruction in children. J. Clin. Periodontol. 34, 294–298 (2007).

At, M., Merchant, A. T., Pitiphat, W., Rimm, E. B. & Joshipura, K. Increased physical activity decreases periodontitis risk in men. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 18, 891–898 (2003).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction. Circulation 121, 586–613 (2010).

Demmer, R. T. et al. Periodontal infection, systemic inflammation, and insulin resistance. Diabetes Care 35, 2235–2242 (2012).

Engebretson, S. & Kocher, T. Evidence that periodontal treatment improves diabetes outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Periodontol. 84, 1340017 (2013).

Preshaw, P. M. et al. Periodontitis and diabetes: A two-way relationship. Diabetologia 55, 21–31 (2011).

Paraskevas, S., Huizinga, J. D. & Loos, B. G. A systematic review and meta-analyses on C-reactive protein in relation to periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 35, 277–290 (2008).

Libby, P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 2045–2051 (2012).

Kaptoge, S. et al. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: An individual participant meta-analysis. The Lancet 375, 132–140 (2010).

Demmer, R. T., Jacobs, D. R. & Desvarieux, M. S. Periodontal disease and incident type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 31, 1373–1379 (2008).

Gw, T. Bidirectional interrelationships between diabetes and periodontal diseases: An epidemiologic perspective. Ann. Periodontol. 6, 99–112 (2001).

Salvi, G. E. et al. Inflammatory mediator response as a potential risk marker for periodontal diseases in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients. J. Periodontol. 68, 127–135 (1997).

Ambrose, J. A. & Barua, R. S. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43, 1731–1737 (2004).

Dietrich, T., Sharma, P., Walter, C., Weston, P. & Beck, J. The epidemiological evidence behind the association between periodontitis and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 40, 12062 (2013).

Tonetti, M. S. & Van Dyke, T. E. Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 40, 12089 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XL, HW: Contributed to conception, design, data acquisition and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. YL: Contributed to conception, design, data acquisition and interpretation, performed all statistical analyses, drafted, and critically revised the manuscript. YW, WS: Contributed to conception, design, data acquisition and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. LJ, WL, JC: Contributed to conception, design, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Li, Y., Wang, H. et al. Association between life’s essential 8 and periodontitis in U.S. adults. Sci Rep 14, 31014 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82195-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82195-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Central adiposity indices and inflammatory markers mediate the association between life’s crucial 9 and periodontitis in US adults

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)