Abstract

The recent clinical outcomes of multi-regimen chemotherapy included prolonged survival and a high rate of conversion to surgery in Asian patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. The ability of single-operator cholangioscopy (SOC) to detect and stage extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCC) in intraductal lesions is becoming more important in determining the extent of surgery. The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of SOC in surgical planning for extrahepatic CCC. We reviewed the consecutive data of patients who received nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine-cisplatin for the management of extrahepatic CCC and underwent preoperative evaluations between June 2020 and August 2022. SOC was performed to determine the precise extent of the disease in patients with a good response to chemotherapy who were considering surgical treatment. Among the 38 patients included, 30 (79%) were diagnosed with perihilar CCC, six (16%) with distal CCC, and two (5%) with intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct. Intraductal evaluation with SOC altered disease extent defined by previous imaging findings in 14 (37%) patients. In those patients, five (36%) were changed to less extensive surgery, four (29%) to conversion surgery, four (29%) avoided surgery, and one (7%) was changed to more extensive surgery. Among the 38 included patients, 27 (71%) underwent surgery, and the accuracy of the visual impressions was 93%, as confirmed by the surgical pathology report. In conclusion, SOC examination of patients with potentially resectable extrahepatic CCC was more precise than conventional diagnostic evaluations and could help in planning surgical options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCC) is an aggressive and rare malignancy that arises from the epithelial cells of the bile ducts. CCC is classified into intrahepatic, perihilar, and extrahepatic CCC, with perihilar CCC being the most common1,2. Global mortality rates for CCC rose across the periods, as documented by the WHO and the Pan American Health Organization from data collected across 32 locations, including Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Oceania.3 Mortality rates for CCC remain consistently higher among men than women globally and are notably more elevated in Asian countries compared to Western regions.4 Particularly in Thailand, China, and South Korea, incidence rates exceed 6 cases per 100,000 individuals.4 Liver fluke infections currently represent a major risk factor for CCC in Southeast Asia, while outside this region remain largely unknown.5 Risk factors for non-fluke-related extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma include primary sclerosing cholangitis, Caroli disease, choledochal cysts, and choledocholithiasis.5.

Despite advancements in imaging techniques, CCC often presents at advanced stages due to its subtle early symptoms, resulting in poor prognosis and limited treatment options1. So, accurate diagnosis and staging are critical to determining resectability and optimizing patient outcomes6,7.

Traditional diagnostic approaches, such as Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) combined with brush cytology or fluoroscopy-guided biopsy, have been widely used. However, these methods are often hampered by their limited diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, which frequently results in inconclusive diagnoses, especially for indeterminate biliary strictures8,9. In one study, the sensitivity of visualization was higher using SOC compared to ERCP (95.5%vs. 66.7%, p = 0.02).9Another study reported a sensitivity of 69.6% for ERCP when used with biopsy forceps.10 As a result, more accurate and efficient tools are required to improve early detection and therapeutic decision-making in CCC. In recent years, Single-Operator Cholangioscopy (SOC) has emerged as a game-changing diagnostic tool in the evaluation of bile duct disorders. SOC allows for direct visualization of the biliary tree and facilitates real-time, targeted biopsies of suspicious lesions. Direct visualization of the bile duct represents a significant advancement over traditional assessment of bile duct irregularities and thickening via cholangiogram with fluoroscopy. The SpyGlass™ Direct Visualization System (SGDVS; Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, MA, USA) for SOC was launched in 2007. The first-generation SpyGlass™ system included essential components such as a light source, monitor, access and delivery catheter (SpyScope), and an optical probe (SpyGlass) with an irrigation pump. This optical system was subsequently upgraded to a video-based system (SpyGlass™ DS) to enhance image quality.11 This technology has demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy compared to conventional methods, especially in the detection and assessment of cholangiocarcinoma9,12,13. Furthermore, SOC’s enhanced imaging capabilities improve tissue acquisition and increase the diagnostic yield, which is particularly crucial for the preoperative staging of CCC9.

Recently, since the ABC-02 study using combined chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin, various combination chemotherapies have been attempted for patients with CCC14,15,16,17,18. Among the combination therapies, the clinical outcomes of a phase II study of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine-cisplatin showed prolonged survival, with an observed median overall survival (OS) of 19.2 months and median progression-free survival (PFS) of 11.8 months17. In a phase III study (SWOG 1815), the triplet regimen (gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab-paclitaxel) did not improve OS in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer18. However, exploratory analyses showed higher OS and PFS in patients with locally advanced disease. Also, a recent clinical outcome of the triplet regimen was prolonged survival in Asian patients with advanced biliary tract cancer in a real-world setting19. The triplet regimen demonstrated a down-staging effect through a high response rate20. The study showed that the pathologic stages after surgery were down-staged in both patients with intrahepatic CCC and extrahepatic CCC compared to the initial clinical stage before chemotherapy20. Due to the discrepancies in the clinical and pathological stages, the ability of single-operator cholangioscopy (SOC) to detect extrahepatic CCC in intraductal lesions is becoming more important in determining the extent of surgery.

The preoperative staging methods for extrahepatic CCC include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), intraductal ultrasonography, direct peroral cholangioscopy, and SOC21,22,23,24. Despite the usefulness of imaging techniques, such as CT and MRI, in evaluating the spread of extrahepatic CCC25, their diagnostic accuracy, particularly in terms of specificity, is inadequate due to the challenge of differentiating cancer invasion from inflammation24. SOC has received attention among the preoperative staging methods. In particular, many studies on mapping biopsies through SOC in extrahepatic CCC have been conducted. One study showed that the surgical treatment plan could be changed by SOC. In the study, the proportion of changed surgical plans was 34%: 10% had more extensive surgery, 65% had less extensive surgery, and 25% avoided surgery26. The correlation between surgical and cholangioscopic pathology was 88%.26 However, limitations exist in determining cancer invasion in intraductal lesions solely through a biopsy, or confirming cancer-free area which cancer was not detected in the biopsy specimen. For example, desmoplastic tumors and those with submucosal spread have low biopsy yields27. No studies have been conducted on intraductal staging using visual impressions in SOC for the preoperative evaluation of extrahepatic CCC.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of SOC in surgical planning for extrahepatic CCC.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

Three hundred and eighty-nine consecutive patients received chemotherapy with gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab-paclitaxel for extrahepatic CCC between June 2020 and August 2022 in a single academic referral center. Of them, 153 patients were planned for surgery by the multidisciplinary team in the center. SOC was necessary to confirm the extent of intraductal involvement that could not be determined by imaging studies or in cases where more extensive surgery, such as hepatopancreatoduodenectomy (HPD), was anticipated. The study inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with extrahepatic CCC by endoluminal biopsy during previous ERCP procedure, (2) patients receiving nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine-cisplatin, (3) patients receiving SOC with the SpyGlass™ Direct Visualization System for preoperative evaluation. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the examinations. In all patients, the purpose of SOC was to evaluate its role in the preoperative intraductal staging of extrahepatic CCC. CT and MRI were performed before the procedure. The present study protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bundang CHA Medical Center (IRB number: 2023-03-073). The requirement for informed patient consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Bundang CHA Medical Center because of the retrospective study design.

Endoscopic procedure

All endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures with therapeutic video duodenoscopy (TJF-260 V) were performed by interventional endoscopists and attending physicians with experience of at least 1000 cases. All ERCPs were performed with patients in the prone position. A cholangioscope was inserted into the bile duct over a 0.025-inch hydrophilic guidewire (Olympus VisiGlide 2 Guidewire; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The single-operator cholangioscope was inserted into the biliary duct with guidewire assistance. SOC was performed using a digital singleoperator cholangiopancreatoscopy system (SpyGlass DS Direct Visualization System or SpyGlass DS II Direct Visualization System, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA).

Following the initial characterization of the biliary stricture by fluoroscopy, the target duct was accessed by inserting a guidewire, and a delivery catheter (SpyScope, Boston Scientific) was placed proximal to the stricture. After irrigating the bile duct with saline, a thorough examination of the biliary tree was conducted during withdrawal, categorizing each segment (right posterior duct, right anterior duct, right hepatic duct, left hepatic duct, common hepatic duct, and distal common bile duct), and visually assessing any abnormalities in the ducts. If a lesion was identified, fluoroscopic imaging was used to precisely locate it. Intraductal involvement was determined by visual inspection and post-examination analysis using still images. The confirmation of the bile duct’s location during SOC was achieved by comparing it to the results of a cholangiography performed prior to the SOC examination using a guidewire inserted through the SpyScope channel under fluoroscopic guidance. Plastic stents were inserted at the end of the procedure to ensure proper drainage.

Visual impressions of biliary lesions were classified as malignant according to Mendoza criteria if one of the following visual findings were detected: (1) tortuous and dilated vessels, (2) irregular nodulations, (3) raised intraductal lesions, (4) irregular surface with or without ulcerations, or (5) friability13,28.

Outcomes measures

The outcome measures for this study were the rate of plan changes after SOC and visual impression accuracy. Visual impression accuracy was defined as a proposed clinical stage via SOC identical to the pathological stage determined after surgery. Visual impression accuracy was used to evaluate the ability of SOC to detect mucosal cancerous extension preoperatively in patients with potentially resectable extrahepatic CCC and changes to the surgical approach based on the findings. In all surgical cases, we compared previous imagiologic anatomic classifications with those made by SOC. Anatomic classifications were based on the Bismuth-Corlette classification system, which provides an anatomic description of the tumor location and longitudinal extension into the biliary tree.

Results

Baseline characteristics

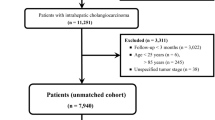

Of the 389 patients who received gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab-paclitaxel for extrahepatic CCC during the study period, 153 were planned for surgery by the multidisciplinary team. A total of 115 patients were excluded for the following reasons: cases where the disease had progressed during preoperative assessment for surgery (n = 23), cases where the tumor size remained stable following chemotherapy, rendering surgery unfeasible (n = 5), cases where the tumor responded to chemotherapy but the patients were deemed ineligible for surgery (n = 9), cases where the tumor extent was sufficiently delineated through imaging modalities such as CT and MRI prior to SOC (n = 68), and cases of patient loss to follow-up (n = 10). After 115 patients were excluded, 38 patients underwent ERCP and SOC. Thirty of these patients were classified as having perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, six with distal CCC, and two with intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct (IPNB) (Fig. 1). The mean age of the patients was 63.9 years, and the portion of male participants was 68%. Five patients had perihilar CCC of Bismuth type I, five (13%) had type II, 12 (32%) had type III, and eight (21%) had type IV (Table 1).

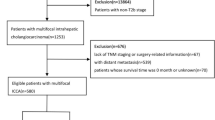

Outcomes

Figure 2 shows a diagram depicting how SOC affected whether the initial treatment plan was performed as scheduled or changed. The rate of plan change after SOC was as follows. Of the treatment plans, 24 (63%) remained as scheduled, and 14 (37%) were changed. Among the patients whose plans changed, five (36%) were changed to less extensive surgery, four (29%) were changed to conversion surgery, four (29%) avoided surgery, and one (7%) was changed to more extensive surgery. In visual impression accuracy, the treatment plans decided via SOC and surgery were identical in 25 (93%) cases. There were two (7%) discrepancies between the plan and surgery (Fig. 3). The list of patients undergoing SOC is shown in Table 2.

Rate of changing the plan after single-operator cholangioscopy. Among total 38 patients underwent ERCP and SOC, the rate of plan change after SOC was as follows. Of the treatment plans, 24 (63%) remained as scheduled, and 14 (37%) were changed. Among the patients whose plans changed, five (36%) were changed to less extensive surgery, four (29%) were changed to conversion surgery, four (29%) avoided surgery, and one (7%) was changed to more extensive surgery.

Visual impression accuracy of single-operator cholangioscopy in patients with potentially resectable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Among the 27 patients with underwent surgery, the treatment plans decided via SOC and surgery were identical in 25 (93%) cases. There were two (7%) discrepancies between the plan and surgery.

Figure 4 shows the treatment methods of the patients after SOC was performed. Among the 30 patients with perihilar CCC, 19 (63%) underwent surgery and 11 (37%) did not. In the patients undergoing surgery, nine (30%) had hepatectomies, five (17%) had hepatopancreaticoduodenectomies (HPDs), three (10%) had pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomies (PPPDs), one (3%) had a radical bile duct resection, and one (3%) underwent an open and closure procedure. All six patients with infiltrative-type distal CCC underwent PPPD. Both patients with IPNB underwent left hepatectomy.

Treatment methods of the patients after single-operator cholangioscopy. Among total 38 patients underwent ERCP and SOC, thirty of these patients were classified as having perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (CCC), six with distal CCC, and two with intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct (IPNB). Among the 30 patients with perihilar CCC, 19 (63%) underwent surgery and 11 (37%) did not. In the patients undergoing surgery, nine (30%) had hepatectomies, five (17%) had hepatopancreaticoduodenectomies (HPDs), three (10%) had pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomies (PPPDs), one (3%) had a radical bile duct resection, and one (3%) underwent an open and closure procedure. All six patients with infiltrative-type distal CCC underwent PPPD. Both patients with IPNB underwent left hepatectomy.

Representative cases

Representative cases of less-extensive surgery, more-extensive surgery, and conversion surgery are presented. In the first case, a 69-year-old female was diagnosed with hilar CCC, Bismuth type IIIa. Tumor involvement in the right anterior branch and the intrapancreatic portion of the bile duct was seen in MRI and CT. The initial MRI coronal view showed tumor involvement of the right anterior branch and intrapancreatic portion of the common bile duct (Fig. 5A and B). The initial CT scan coronal view showed tumor encasement of the right hepatic artery and abutment with the proper hepatic artery (Fig. 5C). Tumor encasement around the right hepatic artery and involvement of the intrapancreatic portion improved after four cycles of chemotherapy. The follow-up CT scan coronal view showed improvement in the tumor encasement around the right hepatic artery and reduced tumor involvement in the intrapancreatic portion of the common bile duct (Fig. 5D and E). After performing SOC, the surgical plan was changed from HPD to right extended hepatectomy. SOC revealed severe fibrotic changes at the intrapancreatic area without evidence of tumor involvement (Fig. 5F and K). The surgical findings noted free resection margins of the proper hepatic artery and intrapancreatic duct. Microscopic examination showed severe fibrosis without tumor involvement at the margin of the resected distal common bile duct (Fig. 6).

Images of less-extensive surgery. Initial MRI coronal view shows the tumor involving the right anterior branch (A) and the intrapancreatic portion of the common bile duct (B). The initial CT scan coronal view shows the tumor encasing the right hepatic artery and abutting the proper hepatic artery (C). Follow-up CT scan coronal view shows tumor involvement of the intrapancreatic portion of the common bile duct (D) and tumor encasement around the right hepatic artery (E). Fluoroscopic views of the cholangioscopy position (F–H) and cholangioscopic views of tumor involvement at the same level as the radiologic position (I–K). Cholangioscopy reveals severe fibrotic changes in the intrapancreatic area without evidence of tumor involvement (K).

Surgical findings (A, B) and microscopic findings (C, D). Severe inflammation and fibrosis around the common bile duct are noted (circle) (A). Right hepatectomy without pancreaticoduodenectomy could be done because of the free resection margins of the proper hepatic artery and intrapancreatic duct (B). Microscopic examination shows severe fibrosis without tumor involvement at the margin of the resected distal common bile duct (C, HE; D, Masson trichrome staining, X100).

In the second case, a 56-year-old male was diagnosed with hilar CCC, Bismuth type I. The initial CT scan coronal view and MRCP showed a focal infiltrative lesion at the common bile duct without any other abnormal lesions (Fig. 7A and B). The cholangioscopic view showed diffuse infiltration of the tumor through the common bile duct and a satellite lesion at the right posterior duct (Fig. 7C). After performing SOC, the surgical plan was changed from PPPD to HPD.

Images of case 2. The initial CT scan coronal view (A) and MRCP (B) show a focal infiltrative lesion (arrow) at the common bile duct without any other abnormal lesions. The cholangioscopic view (C) reveals diffuse infiltration of the tumor through the common bile duct and a satellite lesion at the right posterior duct.

In the third case, a 39-year-old male was diagnosed with hilar CCC, bismuth type I. However, initial cholangioscopic view showed diffuse infiltration of tumor through the common bile duct, hilar area, left main duct, right anterior duct and posterior bifurcation area (Fig. 8A). Fortunately, after 7 cycles of chemotherapy, follow-up cholangioscopic view showed the fibrotic change at the left main duct without the evidence of tumor involvement (Fig. 8B). So, he underwent right extended hepatectomy and PPPD. On surgical findings, gross pathologic finding showed the involvement of tumor existed only int the common bile duct (Fig. 8C). Microscopic examination shows no remnant tumor cell at the left main duct (Fig. 8D and F).

Images of case 3. The initial cholangioscopic view (A) shows diffuse infiltration of the tumor through the common bile duct, hilar area, left main duct, right anterior duct, and posterior bifurcation area. The follow-up cholangioscopic view (B) shows fibrotic changes in the left main duct without evidence of tumor involvement. The gross pathologic finding (C) shows that the tumor is confined to the common bile duct. Microscopic examination shows no residual tumor cells in the left main duct (D, HE, X 100), right main duct (E, HE, X 100), or hilar area (F, HE, X 12).

Discussion

We assessed the diagnostic accuracy of SOC in the preoperative intraductal staging of patients with extrahepatic CCC treated with gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab-paclitaxel. The study results demonstrated a 37% plan change rate after SOC. The discrepancies observed in diagnoses established through conventional imaging modalities (CT, MRI, ERCP) hold clinical significance. For instance, the SOC may help prevent intraoperative situations where surgery ultimately proves infeasible, despite preoperative assessments intended to guide surgical planning. While a direct comparison was limited by the retrospective nature of the studies, the observed rate of 37% was notably higher than the 21% reported in previous study.11 In particular, the visual impression accuracy of SOC, defined as whether the proposed clinical stage via SOC was identical to the pathological stage determined after surgery, was 93%. The results indicate that visual impressions through SOC is needed for the preoperative intraductal staging of extrahepatic CCC. This was a novel study on intraductal staging, relying solely on visual impressions through SOC for the preoperative evaluation of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma following chemotherapy.

The triplet regimen has demonstrated a down-staging effect with a high rate of conversion surgery of about 20%.17,20 Also, if less extensive surgery is possible because of a reduction in the extent of cancer invasion after undergoing the triplet regimen, older patients may better tolerate surgery. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to accurately determine the extent of cancer invasion after chemotherapy. However, especially after chemotherapy, determining the extent of bile duct invasion by imaging becomes challenging. The reason for the thickening of the bile duct wall could be attributed not just to fibrosis but also to inflammation and the spread of cancer24. Also, the longitudinal spread of cholangiocarcinoma may be underestimated because CT and MRI have low specificity (CT 52.6%, MRI 51.4%) relative to their high sensitivity (CT 84.3%, MRI 90.3%).29,30,31 Therefore, preoperative staging following chemotherapy may serve as a crucial indicator beyond the general indications for SOC. Utilizing SOC, the extent of bile duct involvement beyond the second branch of both intrahepatic bile ducts or within the intrapancreatic bile duct could be accurately assessed, facilitating the determination of the surgical resection margin. For instance, if both intrahepatic bile ducts were involved, complete liver resection was not viable, thereby limiting surgical options. Furthermore, when defining the surgical scope, it was essential to determine not only the resection of perihilar and distal bile ducts but also the necessity of resecting bile ducts within the pancreas. Resection of the intrapancreatic bile ducts typically requires a PPPD. The surgical extent could vary significantly depending on the resection of the liver (perihilar bile ducts) and distal bile duct (with or without intrapancreatic bile duct). Conventional diagnostic modalities such as CT, MRI, and ERCP primarily assessed irregularities and thickening of bile duct walls. However, SOC enabled direct endoscopic visualization of biliary lesions, which is thought to significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy. As chemotherapy for cholangiocarcinoma improves, this indicator is likely to become even more significant.

Our study had several strengths. Firstly, SOC was highly beneficial for planning surgical treatment. Since the ABC-02 study, which used combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin, the SWOG-1815 study (gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab-paclitaxel) demonstrated improved survival rates in patients with locally advanced CCC18. Additionally, studies incorporating immune checkpoint inhibitors showed survival benefits in cholangiocarcinoma patients15,16. These newly added drugs not only increased survival rates compared to the ABC-02 trial but also expanded the opportunities for conversion surgery.

The triplet regimen exhibited a significant down-staging effect due to its high response rate20. This enhancement in chemotherapy effectiveness has further emphasized the importance of preoperative staging26. In addition to cross-sectional imaging techniques such as CT or MRI, detailed examination by SOC has also become necessary. SOC can provide information on surgical margins and insight into surgical treatment plans, such as skipped lesions and lateral sparing lesions.

Second, visual impressions alone, rather than a combination of visual impressions and histological examination, demonstrated a high accuracy rate. Many studies on the role of SOC in preoperative staging typically included histological examinations, such as biopsies using SpyBite™ forceps. However, in our study, relying solely on visual impressions was highly accurate. In a meta-analysis, the overall sensitivity of conventional cytology from ERCP, common diagnostic tool for cholangiocarcinoma, was found to be 41.6% (99%CI: 38.4-44.8%).32 In a recent systematic review, the study found that sensitivity of SOC [94% (95%CI: 89-97%)] is higher than SOC-guided biopsy [79% (95%CI: 72-84%).7,33 This suggests that mapping biopsies may not be obligatory when examining surgical margins through SOC. Also, relying solely on a biopsy has limitations in determining cancer invasion within intraductal lesions, particularly in desmoplastic tumors27. Moreover, in cases of fibrosis following chemotherapy, it is challenging to accurately determine cancer infiltration with only one or two biopsy specimens. And, in this study, no cancer cells were identified in the surgical tissues of patients with fibrotic changes confirmed by SOC. This is supported by the explanations in the two reported classifications of the visual impression of biliary lesions, Mendoza criteria and the Monaco classification13,28. Utilizing SOC’s high visual accuracy, it is necessary to actively incorporate it into preoperative evaluations for patients with cholangiocarcinoma. In the future, prospective studies should also be conducted to compare whether additional bile duct biopsies are necessary.

Third, this was the first study to identify intraductal lesions using SOC for the preoperative staging of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after chemotherapy, especially with gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab-paclitaxel. Recent SOC studies primarily focused on initial staging and the pathologic mapping of CCC. However, due to the increased response rates and conversion surgery cases resulting from new chemotherapy combinations, the number of preoperative staging cases by SOC after chemotherapy has increased. Distinguishing the cause of bile duct wall thickening in cross-sectional images is challenging, especially after chemotherapy. The cause may be not only fibrosis but also inflammation or cancer invasion9. This study also utilized the Mendoza criteria employed in previous studies, and the diagnostic accuracy of SOC in this study was not different from that of the study used for initial staging. While the ideal research approach would involve comparing SOC results before and after chemotherapy, conducting SOC when the malignant biliary stricture is rigid before chemotherapy presents challenges.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, pathological examinations were not conducted during SOC in this study. A biopsy is essential to enhance the specificity of preoperative examinations. Also, one study showed that the specificity for SOC-guided biopsy [100% (95%CI:97-100%)] was higher compared to SOC visual impression [86% (95%CI: 76-92%).7,33 However, considering the high sensitivity of SOC observed in this study, it is believed that visual impressions alone are sufficient for identifying tumorous lesions. Additionally, when performing a biopsy during SOC using SpyBite™, the specimen size is smaller than that obtained by a forceps biopsy in ERCP11,34. This limitation in specimen size may have impacted sensitivity, even though targeted biopsies were performed in SOC11. Second, the periductal infiltrative type of CCC could not be diagnosed based solely on SOC visual impressions. However, making an accurate diagnosis of the CCC type is challenging, even on cross-sectional images. The mass-forming type of CCC is easily identifiable in cross-sectional images, and the intraductal type of CCC is readily diagnosed by SOC. Additionally, despite performing a biopsy during SOC, confirming tumor invasion in the infiltrative type of CCC may still be difficult. Third, performing SOC requires more procedure time and incurs higher costs than performing ERCP alone. However, SOC is essential as a preoperative test because an accurate diagnosis affects patient prognosis. Additionally, combining ERCP with SOC may yield better diagnostic accuracy compared to using ERCP, Endoscopic ultrasound or Intraductal ultrasonography.

In conclusion, SOC examinations in patients with potentially resectable extrahepatic CCC were more precise than conventional diagnostic evaluations and could help plan surgical options. A prospective study is warranted to evaluate the potential impact of SOC on surgical strategies for the treatment of extrahepatic CCC. Integrating SOC as an additional modality into existing diagnostic methods is expected to enhance accuracy in determining the surgical scope.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

References

Banales, J. M. et al. Expert consensus document: Cholangiocarcinoma: current knowledge and future perspectives consensus statement from the European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13, 261–280 (2016).

Ilyas, S. I., Khan, S. A., Hallemeier, C. L., Kelley, R. K. & Gores, G. J. Cholangiocarcinoma—evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15, 95–111 (2018).

Bertuccio, P. et al. Global trends in mortality from intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 71, 104–114 (2019).

Banales, J. M. et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 557–588 (2020).

Brindley, P. J. et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 65 (2021).

Kawashima, H. et al. Endoscopic management of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Dig. Endosc. 34, 1147–1156 (2022).

Kulpatcharapong, S., Pittayanon, R., Kerr, S. J. & Rerknimitr, R. Diagnostic performance of digital and video cholangioscopes in patients with suspected malignant biliary strictures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Endosc. 36, 2827–2841 (2022).

Almadi, M. A. et al. Using single-operator cholangioscopy for endoscopic evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures: results from a large multinational registry. Endoscopy 52, 574–582 (2020).

Gerges, C. et al. Digital single-operator peroral cholangioscopy-guided biopsy sampling versus ERCP-guided brushing for indeterminate biliary strictures: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 91, 1105–1113 (2020).

Yamamoto, K. et al. Evaluation of novel slim biopsy forceps for diagnosis of biliary strictures: single-institutional study of consecutive 360 cases (with video). World J. Gastroenterol. 23, 6429–6436 (2017).

Pereira, P. et al. Role of Peroral Cholangioscopy for diagnosis and staging of biliary tumors. Dig. Dis. 38, 431–440 (2020).

Minami, H. et al. Clinical outcomes of digital cholangioscopy-guided procedures for the diagnosis of biliary strictures and treatment of difficult bile duct stones: a single-center large cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 10 (2021).

Sethi, A. et al. Digital single-operator Cholangioscopy (DSOC) improves Interobserver Agreement (IOA) and accuracy for evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures: the Monaco classification. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 56, e94–e97 (2022).

Valle, J. et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 362, 1273–1281 (2010).

Oh, D. Y. et al. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced biliary tract Cancer. NEJM Evid. 1, EVIDoa2200015 (2022).

Kelley, R. K. et al. Pembrolizumab in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared with gemcitabine and cisplatin alone for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (KEYNOTE-966): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 401, 1853–1865 (2023).

Shroff, R. T. et al. Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, and nab-Paclitaxel for the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancers: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 5, 824–830 (2019).

Shroff, R. T. et al. SWOG 1815: a phase III randomized trial of gemcitabine, cisplatin, and nab-paclitaxel versus gemcitabine and cisplatin in newly diagnosed, advanced biliary tract cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, LBA490–LBA490 (2023).

Cheon, J. et al. Real-world efficacy and safety of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine-cisplatin in patients with advanced biliary tract cancers: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 13, 17588359211035983 (2021).

Choi, S. H. et al. Clinical feasibility of curative surgery after nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine-cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery 173, 280–288 (2023).

Tamada, K. et al. Preoperative staging of extrahepatic bile duct cancer with intraductal ultrasonography. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 90, 239–246 (1995).

Nishikawa, T. et al. Preoperative assessment of longitudinal extension of cholangiocarcinoma with peroral video-cholangioscopy: a prospective study. Dig. Endosc. 26, 450–457 (2014).

Ogawa, T. et al. Usefulness of cholangioscopic-guided mapping biopsy using SpyGlass DS for preoperative evaluation of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a pilot study. Endosc Int. Open. 6, E199–E204 (2018).

Ruys, A. T. et al. Radiological staging in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Radiol. 85, 1255–1262 (2012).

Campbell, W. L. et al. Using CT and cholangiography to diagnose biliary tract carcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 177, 1095–1100 (2001).

Tyberg, A. et al. Digital pancreaticocholangioscopy for mapping of pancreaticobiliary neoplasia: can we alter the surgical resection margin? J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 53, 71–75 (2019).

Korc, P. & Sherman, S. ERCP tissue sampling. Gastrointest. Endosc. 84, 557–571 (2016).

Kahaleh, M. et al. Digital single-operator cholangioscopy interobserver study using a new classification: the Mendoza classification (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 95, 319–326 (2022).

Joo, I., Lee, J. M. & Yoon, J. H. Imaging diagnosis of Intrahepatic and Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: recent advances and challenges. Radiology 288, 7–13 (2018).

Sakamoto, E. et al. The pattern of infiltration at the proximal border of hilar bile duct carcinoma: a histologic analysis of 62 resected cases. Ann. Surg. 227, 405–411 (1998).

Yoo, J. et al. Comparison between contrast-enhanced computed tomography and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for Resectability Assessment in Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Korean J. Radiol. 24, 983–995 (2023).

Burnett, A. S., Calvert, T. J. & Chokshi, R. J. Sensitivity of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography standard cytology: 10-y review of the literature. J. Surg. Res. 184, 304–311 (2013).

Subhash, A., Buxbaum, J. L. & Tabibian, J. H. Peroral cholangioscopy: update on the state-of-the-art. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 14, 63–76 (2022).

Sekine, K. et al. Peroral cholangioscopy-guided targeted biopsy versus conventional endoscopic transpapillary forceps biopsy for biliary stricture with suspected bile duct cancer. J. Clin. Med. 11 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was presented at ASGE Evolving ERCP Techniques during Digestive Disease Week, May 6-9, 2023, Chicago, IL (Gastrointest Endosc 2023;97: AB589-AB590).

Funding

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (or Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program) (20017645, The development of manufacturing technology for interventional medical devices based on biocompatible polymer nanofiber) funded By the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guarantor of the article: C-IK is accepting full responsibility for this study. He had access to the data and control over the decision to publish. Study concept and design: C-IK, MJS, SPS; principal investigation: C-IK; acquisition of data: MJS, SPS, GK; analysis and interpretation of data: MJS, SPS, IK, SHL, SJY, GK; drafting of the manuscript: C-IK; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KHK; and review of the manuscript: BK, HJC. All authors read, corrected, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sung, M.J., Shin, S.P., Kwon, CI. et al. Diagnostic cholangioscopy for surgical planning of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 3654 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82205-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82205-0