Abstract

Chlamydiosis is a common infectious disease impacting koalas and is a major cause of population decline due to resulting mortality and infertility. Polymorphisms of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes influence chlamydial disease outcomes in several species but koala studies have produced variable results. We aimed to identify the MHC II DAB and DBB repertoire of koalas from Liverpool Plains, NSW, a population heavily impacted by chlamydiosis. We compared variants between two studies, age cohorts and chlamydial infertility groups. Four DBB and eight DAB alleles were identified. The mean number of DAB alleles per individual increased and allele frequencies differed relative to a previous study, however the mean number of DBB alleles per individual decreased generationally, between age cohorts. DAB allele frequencies differed among fertility groups but contributing alleles could not be identified. While there is a likely role of MHCII in the complex pathogenesis of chlamydiosis, this study suggests that single gene association studies are not appropriate for understanding the impact of host genetics on koala chlamydiosis. A shift to larger multivariate studies is required to yield functional information on complex immunological interactions, and to inform targeted koala conservation across its diverse range and host–pathogen–environment contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) is an arboreal marsupial that is faced with significant decline in large parts of its range, associated with, but not limited to, land clearing, vehicle collision, bushfires and disease1,2,3,4,5,6. This decline has led to koala populations in Queensland (Qld), New South Wales (NSW) and the Australian Capital Territory being listed as ‘Endangered’ under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999) in 20227,8. Modelling indicates that chlamydial disease is a major driver of koala population decline1.

Chlamydiosis of koalas is predominantly caused by Chlamydia pecorum and is the most common infectious disease impacting koala populations9, accounting for over 20% of koala hospitalisations in a major NSW rescue facility10, and 18% of total mortality in a longitudinal study of wild animals in south-east Qld (SE Qld)11. C. pecorum infection occurs in the majority of koala populations throughout mainland Australia, and prevalence estimates range from 20–90%, however chlamydiosis is more common and severe in the northern populations of NSW and Qld compared to southern populations of Victoria and Southern Australia12. The pathogen infects mucosal epithelial cells of the conjunctiva, urinary and reproductive tracts, but its impact on populations is primarily due to its role in inflammation and fibrosis of the female reproductive tract and development of ovarian bursal cysts, inducing infertility, and reducing the reproductive potential of populations13,14,15. Variability in disease is generally a result of complex interactions, with host age and sex, chlamydial load and strain, infection site, koala retroviral expression and habitat stressors all being proposed as determinants of susceptibility to chlamydiosis in koalas but further work is needed to fully understand these interactions6,9,10,16,17,18,19,20,21.

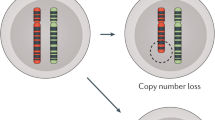

Host genetics can be an important factor in the outcome of disease, in particular major histocompatibility complex (MHC) diversity and variants have been linked to chlamydial disease outcome in koalas. MHC genes encode surface proteins responsible for the presentation of antigens to T-lymphocytes to initiate the adaptive immune response22. Greater diversity at MHC loci confers a more diverse repertoire of peptide-binding regions (PBRs), influencing immunological response and, often, fitness23,24. While both classes of MHC may interact with chlamydial antigens, previous work has focused on MHC class II (MHCII) genes, expressed only on antigen presenting cells responsible for the presentation of phagocytosed extracellular antigens to CD4 helper T-lymphocytes22. MHCII genes influence chlamydial disease progression in several species including humans and mice25,26,27. Four MHCII subfamilies have been described in marsupials, consisting of the alpha and beta subunits of DA, DB, DC and DM, encoded by the alpha and beta genes, respectively28,29. In koalas, diversity at the beta subunits of the DA and DB genes (DAB and DBB) is greater than that of the alpha subunits and may be reflective of selection pressures at these loci30. While DC and DM genes are present as single copy genes, koala DAB and DBB genes are likely expressed at three distinct loci each30,31, based on number of observed variants per individual. A total of 42 DAB and 26 DBB variants have been identified across the koala’s range with one to six alleles per individual that are not yet assigned to particular loci30,31,32,33,34,35.

Studies have revealed potential associations of MHCII with chlamydiosis in koalas but variants associated with disease outcomes differ among studies16,33,36. The MHCII allele DBB*04 has been associated with higher mean chlamydial heat shock protein (c-hsp60) antibody concentrations, a correlate of chlamydiosis in koalas13,36, and was more prevalent in koalas that progressed to urogenital tract disease compared to those that did not33. The role of MHCII allele DAB*10 is less clear, with contradicting findings in two studies based on disease progression. DAB*10 was more common in “past infected” koalas than “healthy” koalas36, but later found to be more prevalent in koalas that did not progress to urogenital tract disease compared to those that did, being 5.49 times less likely to progress to this state of disease when individuals possessed this allele33. In addition, DBB*02 was more common in older koalas36 and the absence of DBB*03 was associated with overall clinical disease16. Differing findings may be a result of several factors including chance, methodological and demographic differences among studies, unclear disease definition due to limited availability of longitudinal data and comprehensive animal assessment, and the complex and multifactorial nature of chlamydiosis pathogenesis.

In an attempt to minimise ambiguity arising from broad definitions of disease that has hampered previous studies, we conducted an association study utilising small but highly defined sample groups based on chlamydial infertility. This study uses a high throughput Illumina amplicon deep-sequencing approach to identify the MHCII DAB and DBB repertoire of koalas located in a population south of Gunnedah on the Liverpool Plains in NSW, in which chlamydiosis has increased to high levels in the last decade, with C. pecorum prevalence increasing from approximately 8% in 2008 to 43% in 2010–201137 and further to 66% in 2015–201738 based on PCR results at the ocular and/or urogenital sites. This increase in chlamydia prevalence has coincided with a local population crash in the region. To investigate potential MHC selection associations with disease outcomes we compare diversity with a previous study examining MHC diversity in the same population35, examine variant distribution across age groups and investigate associations with presence or absence of chlamydial infertility.

Results

Study population and categorisation of koalas

Our selective inclusion criteria resulted in a sample size of 21 individuals. The group comprised juvenile (n = 7) and adult koalas (n = 14). The adult group only consisted of female koalas and comprised fertile (n = 5) and infertile (n = 9) koalas. The previous study included 12 individuals from the same location sampled in 201035.

MHCII DAB and DBB variants

From the 21 koalas sampled, four DBB (Fig. 1a) (DBB*01–04, GenBank accession numbers JX109922.1, JX109923.1, JX109924.1, JX109925.1) and eight DAB variants (Fig. 1b) (DAB*10, 15, 18, 19, 21, 23, 25, 26, GenBank accession numbers JX109927.1, JX109928.1, JX109929.1, JX109930.1, JX109931.1, JX109933.1, JX514153.1, JX514154.1) were detected. Koalas had one to two DBB variants per individual, and two to six DAB variants per individual. DAB*18, 19 and 21 were found in most individuals sampled (95%) but were still included in further analysis due to presence of within-group variation. Eight novel sequences were identified in the DADA2 screening at high abundances (over the 25% of total sequences) in several individuals. All unique variants only differed by one base at the seventh last position of the sequence relative to a reference variant, so were manually corrected, based on previously identified ambiguity at the same base position in DAB*25 and DAB*2835, likely representing an artifact rather than true variation. Population genetic diversity statistics including estimates of heterozygosity, inbreeding and HWE are impacted by the multicopy nature of MHCII DAB genes, in which alleles have not been assigned to loci (Table 1).

MHCII variation associated with disease induced selection

The mean number of DAB alleles per individual significantly increased from that found in the previous study35 (n = 12, x̄ = 3.3) to the current study (n = 21, x̄ = 4.9, t = 2.04, p = 0.003); the same was not true for DBB with equal means across studies (x̄ = 1.5, t = 2.04, p = 0.90). All alleles from the previous study were identified in the current study, however three additional DAB alleles were also detected that had been previously identified in other populations in the same study (DAB*15, 18, 23; Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S3). Group-wide allele frequency differed at the DAB loci and overall between studies (AMOVA; F (1,30) = 0.032, p = 0.001 and F (1,30) = 0.020, p = 0.023 respectively, Table 2), with DAB*18 being significantly different between current and previous findings (Fisher’s exact test; p = < 0.001, Supplementary Table S3).

The mean number of DBB alleles per individual was significantly greater in the adult group (n = 14, x̄ = 1.6) than the juvenile group (n = 7, x̄ = 1.1; t = 2.09, p = 0.03). Mean number of DAB alleles per individual did not differ between age groups (adult, x̄ = 4.7; juvenile, x̄ = 5.1; t = 2.09, p = 0.40). Although some alleles were found in the adult age group and not in the juvenile age group (DBB*01, 1/14; DBB*04, 2/14; DAB*15, 1/14; Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S4) and DBB*02 and DAB*23 appeared more prevalent in the juvenile group compared to the adult group (Fig. 3), group-wide allele frequency did not differ between the adult and juvenile age groups (AMOVA, Table 3).

MHCII variants associated with chlamydial infection (fertility status)

The mean number of DBB alleles did not differ between the fertile (n = 5, x̄ = 1.8) and the infertile groups (n = 9, x̄ = 1.6; t = 2.18, p = 0.40), nor did the mean number of DAB alleles (fertile, x̄ = 4.6; infertile groups, x̄ = 4.8; t = 2.18, p = 0.80). Some low frequency alleles were only present in the infertile group (DBB*01 and DAB*15), while DAB*10 was more frequent in the infertile (8/9) compared to the fertile (2/5) group and some alleles were more frequent in the fertile than infertile group (DBB*03, DAB*25, DAB*26) (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table S5). DAB allele frequencies significantly differed among fertile and infertile groups (AMOVA; F(1,12) = 0.015, p = 0.032; Table 4), however individual DAB allele frequencies did not differ in post hoc analyses (Fisher’s exact test, Supplementary Table S5). No DBB allele frequencies differed between fertile and infertile groups (AMOVA, Table 4).

Discussion

This project investigated the MHCII DAB and DBB repertoire of 21 koalas from the Gunnedah region of NSW through amplicon deep-sequencing and assessed alleles for association with chlamydial infertility. Diversity at DAB and DBB loci was similar to that reported for other populations of koalas, and despite an increase in mean DAB allele number per individual and significant difference in allele frequency relative to a previous study35, a decrease in mean DBB allele number generationally relative to age groups provides contradictory evidence of generational selection and suggests the impact of methodological differences between studies as well as chance. Mean DAB allele frequencies differed between koala groups with and without chlamydiosis associated infertility, suggesting the possibility of disease-induced selection pressure. However, the use of a strict definition of disease focusing on infertility did not resolve the ambiguity of previous studies regarding association of individual variants with disease. These results suggest that it may be necessary to move from single-gene disease association studies towards multivariate, including genome-wide and mechanistic studies, to elucidate what appear to be complex MHCII-chlamydial interactions.

The number of variants found in the current study indicate MHCII diversity similar to other NSW koala populations. However, genetic diversity statistics are impacted by the multicopy nature of MHCII and should be interpreted in this context. The presence of alleles in our study additional to those in Lau et al.35 may not only be due to selection over time but may, alternatively, be due to increased sample size. Greater sample sizes increase the chance of variant detection, especially for alleles of low frequency, as was the case for some DAB variants detected in the current study (Fig. 2). Lau et al.35 sampled 12 koalas in 2010 from the same location as the current study, which utilised 21 koala samples from 2018–2020. Therefore, we consider the discovery, at low frequency, of variants DAB*15 (previously detected in SE Qld, Lismore and Blue Mountains) and DAB*23 (detected in SE Qld and Port Macquarie) not detected in a previous study (n = 12) on the same population35, was most likely due to the greater sample size of the current study (n = 21), though immigration, cannot be ruled out as a possible cause. The finding of the previously undetected variant DAB*18 (previously detected in Port Macquarie only35) at a high proportion in the current study (95%; Supplementary Table S3) is more difficult to explain; it could be a result of immigration or increased sample size in the current study but the high frequency suggests it is more likely to be due to methodological differences between studies. One sequence conformational polymorphism (OSCP) was used in the previous study, with cloning and sequencing conducted only on variants with unique OSCP patterns, in comparison to amplicon deep sequencing used in the current study which sequenced all variants in targeted genomic regions. It is possible that DAB*18 may have the same OSCP gel pattern as another allele present in Gunnedah, such as DAB*26, however all unique gel patterns have not been published for comparison. Such methodological biases may be responsible for inconclusive findings across koala MHC studies, with various detection methods used. The use of long read sequencing has been suggested for MHC data in a number of species39,40,41, avoiding the potential artifacts of PCR amplification that currently exist, and enabling increased accuracy in describing the complex MHC repertoire. Our study supports further exploration of these approaches to provide a deeper understanding of these complex regions.

Associations of MHCII alleles with disease outcomes in previous studies have been equivocal and our study continues this trend; the use of a individuals from a highly diseased population identified some level of interaction between MHCII and chlamydiosis however no associations of individual MHC alleles with chlamydiosis were observed. The significant increase of mean number of DAB alleles per individual and significant difference of allele frequencies between the previous35 and the current study, may constitute the first signs of genetic selection over at least two generations, for individuals that have a greater number of DAB alleles, reflective of previous findings on the importance of MHC variability in pathogen resistance24. However, this conflicts with our finding of decreased DBB alleles per individual in juvenile relative to adult koalas, which suggests that the individuals with fewer DBB alleles were more reproductively successful. These contradicting findings suggest that observed differences are a result of chance rather than driven by selection of chlamydiosis providing no evidence for selective increase of advantageous or loss of deleterious alleles. Although some rarer alleles occurred only in the current study compared to the previous study (Fig. 2) and in the adult group and not in the juvenile group (Fig. 3), it is very likely this is due to the difference in sample size among groups, allowing for increased detection with increased sample sizes. Interestingly, our data indicated MHCII DAB allele frequency differed among our defined fertility groups (Table 4), but no individual alleles were identified post-hoc, including previously disease-linked alleles DBB*03, DBB*04 or DAB*1016,33,36. It cannot be dismissed that the small sample size of the current study, because of the tightly defined disease groups, may have limited our findings. Greater sample sizes and more generations are required to increase the likelihood of detecting disease-induced selection resulting in emergent population structure. Overall, the lack of evidence for chlamydiosis-induced selection of MHCII genes, in a population of koalas that experienced a high disease burden, demonstrate the need for a shift in research focus away from single gene association studies in highly complex disease interactions.

As a body of work, this and other studies investigating MHC and chlamydiosis in koalas suggest the need for alternative approaches to guide better conservation efforts. MHC association studies have been utilised for decades in a number of disease interactions especially in ecology and conservation studies24 and the findings of such studies have been important in guiding the initial framework of the hosts interaction with pathogens however host response to disease involves many genes and other host, pathogen and environmental factors16,18,19,21,33,38. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) enable the identification of multiple genetic factors contributing to disease. A recent study utilised a GWAS approach using targeted immune gene sequencing accompanied by genome-wide reduced representation sequencing to discover two MHC I genes associated with disease progression and 25 SNPs associated with the resolution of disease in koalas from SE Qld34. The relevance of these to other populations requires further evaluation as host-pathogen-environmental contexts differ among populations, potentially exerting different selective forces. Combining genetic studies with further host, pathogen and environmental data is required to understand the functional importance of genetics in chlamydiosis. In the case of MHC, in-silico conformational modelling may predict the effect of genetic variations in MHC PBRs and associated chlamydial strain-specific peptides on resulting proteins as in other species42,43,44. Findings from multivariate genomic and mechanistic approaches enable more targeted and informed conservation strategies considering all potential genes involved in pathogenesis for the effective management and mitigation of disease risks, while also ensuring the maintenance of genetic diversity of wild populations45.

When placed alongside previous studies, our study supports a role of MHC in chlamydiosis in koalas but, despite the use of tightly defined disease groups in a highly diseased population, failed to identify individual susceptibility-associated variants. Overall, the findings of this study suggest that because of the complexity of host–pathogen interactions we cannot rely solely on single gene association studies to guide conservation efforts. A shift to a combination of multifactorial, genome-wide and mechanistic approaches, are needed to explore the functional significance of immune genes, such as MHC, in comparison to other important variables, to inform targeted koala conservation across its diverse range and host–pathogen-environment contexts.

Materials and Methods

Ethics approval

The research was approved by the University of Sydney Animal Ethics Committee, AEC permit 2019/1547 and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife, license number SL101687. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines46 and were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study population and categorisation of koalas

Samples were selected from previously archived DNA extracts originating from a population of koalas near Gunnedah (Liverpool Plains), NSW (30° 59ʹ S, 150° 16ʹ E), sampled between July 2018 and January 2020. Based on decades of longitudinal study, there has been a marked increase in chlamydiosis in the population over the past decade30,37,38,47, making this an ideal scenario to explore disease induced selection. Metadata for each animal comprised general, clinical, and environmental information collected as part of longitudinal ecological studies. Data was also extracted from a previous study investigating MHCII DAB and DBB variants in 191 koalas from 12 wild populations across eastern Australia, including 12 koalas located in the same region in 201035, to compare with our more recent samples (2018–2020). Generation length of wild koalas has been estimated to range from 6 to 8 years48, therefore these two sampling points are reflective of two generations in the same population with potential cross over, but still enabling evidence of selection following the heavy disease burden.

Koalas were allocated to disease groups based on a narrow definition of disease: chlamydial infertility. “Infertile” koalas were females with no evidence of young as well as signs of para-ovarian cysts based on ultrasound13; “Fertile” koalas were adults carrying pouch young (age class ≥ C, estimated to be over 3 years old, according to teeth wear49) because, although not certain, older koalas are considered highly likely to have been exposed to chlamydiosis in this high prevalence population, representing animals that have responded well to the pathogen. A juvenile group (age class = A, estimated to be under one year old) was considered representative of the progeny of successful (fertile) animals, demonstrating potentially advantageous variants.

PCR for MHCII DAB and DBB

DNA samples used in this study were previously extracted from whole blood using a QIAamp® DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at − 80 °C. Koala-specific MHCII DAB and DBB exon 2 sequences were amplified in all individuals using previously published primers30 with Illumina overhang adapters added for Next-Generation sequencing (Supplementary Table S1). For amplification, Q5® High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (New England BioLabs) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to a final volume of 30 µL, including primers at a final concentration of 400 nM and 5 µL of DNA template. PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s, then 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 56 °C for 20 s, and extension at 72 °C for 10 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 2 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel with SYBR Safe™ stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and visualised under UV-light to confirm specific amplification. PCR products were submitted to the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics (University of New South Wales, Australia) for sample preparation, purification, indexing and sequencing on Illumina MiSeq using 300 bp paired-end reads.

Identification of MHCII variants

FASTQC50 was used to check the quality of reads and identify areas requiring trimming or cleaning. Sequence assembly was conducted using the R (version 4.1.1) program DADA2 (version 1.20.0), adapted to appropriately filter and extrapolate true sequences and their abundance51. Raw sequence read files were input into the program, which filtered out reads with unknown bases, and trimmed sequences to length 150 (forward) and 250 (reverse) for DAB, due to low quality at the end of forward reads; and length 250 (forward) and 250 (reverse) for DBB, with reads shorter than provided lengths being discarded. The default value of truncQ = 2 was used for both DAB and DBB, where the reads were truncated at the first nucleotide with a quality score of 2, then discarded if the read is then shorter than desired read length and if containing greater than two expected errors. The paired-end sequences were then merged, and chimeras were removed.

Following the approach of previous studies32,33, the most abundant sequences following filtering were considered to represent true variants. The top 20 most abundant sequences from each sample were extracted and a threshold of 25% of total sequence that passed filters was used to classify a “true” variant for each sample. Those sequences below the threshold were excluded from further analysis. BLASTN v2.2.30 + 52 was used to query the sample sequences against a custom BLAST database formulated from DAB and DBB reference variants published on NCBI16,33,35,53 (Supplementary Table S2). Individual sequences were assigned to known reference variants with DBB matching only known variants and DAB containing high abundances of both unique and known sequences. These unique sequences from DAB were input into Geneious Prime (version 2021.2.2) for sequence alignment with reference variants and checked for duplicates among the samples. The total percentage of variants present in each sample was calculated, along with the total number of target and non-target sequences.

Sample analysis for MHCII variants

Sequence data was compared: (i) between the adult and juvenile groups, for evidence of disease induced selection across a single generation, (ii) among the findings of all individuals from the current study and a previous study on the same population35 to assess disease induced selection across generations, and (iii) between females categorised as ‘fertile’ and ‘infertile’, to examine associations of variants with a specific chlamydial disease outcome. Allele frequency, heterozygosity, inbreeding coefficients and Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) were conducted using GenoDive (version 3.0554). As alleles cannot be assigned to loci for the multiple copy target genes, variants were assessed as if assigned to a single copy of each locus, which is likely to impact estimates of heterozygosity, inbreeding and HWE. We therefore focused primarily on differences in allelic variation (individual allelic combinations and number of alleles per individual) using t-tests and differences in allele frequencies between defined groups utilising analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) in GenoDive and Fisher’s exact tests in Excel.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

References

Rhodes, J. R. et al. Using integrated population modelling to quantify the implications of multiple threatening processes for a rapidly declining population. Biol. Conserv. 144, 1081–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.12.027 (2011).

Dique, D. S. et al. Koala mortality on roads in south-east Queensland: the koala speed-zone trial. Wildl. Res. 30, 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR02029 (2003).

Gonzalez-Astudillo, V., Allavena, R., McKinnon, A., Larkin, R. & Henning, J. Decline causes of Koalas in South East Queensland, Australia: a 17-year retrospective study of mortality and morbidity. Sci. Rep. 7, 42587. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42587 (2017).

Lunney, D., Gresser, S., O’Neill, L. E., Matthews, A. & Rhodes, J. The impact of fire and dogs on Koalas at Port Stephens, New South Wales, using population viability analysis. Pac. Conserv. Biol. 13, 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1071/PC070189 (2007).

Melzer, A., Carrick, F., Menkhorst, P., Lunney, D. & John, B. S. Overview, critical assessment, and conservation implications of Koala Distribution and abundance. Conserv. Biol. 14, 619–628. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99383.x (2000).

Narayan, E. J. & Williams, M. Understanding the dynamics of physiological impacts of environmental stressors on Australian marsupials, focus on the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). BMC Zool. 1, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40850-016-0004-8 (2016).

Adams-Hosking, C. et al. Use of expert knowledge to elicit population trends for the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Divers. Distrib. 22, 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12400 (2016).

Woinarski, J. & Burbidge, A. A. Phascolarctos cinereus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. e.T16892A21960344. (2016).

McAlpine, C. et al. Time-delayed influence of urban landscape change on the susceptibility of koalas to chlamydiosis. Landsc. Ecol. 32, 663–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-016-0479-2 (2017).

Griffith, J. E., Dhand, N. K., Krockenberger, M. B. & Higgins, D. P. A retrospective study of admission trends of koalas to a rehabilitation facility over 30 years. J. Wildl. Dis. 49, 18–28. https://doi.org/10.7589/2012-05-135 (2013).

Beyer, H. L. et al. Management of multiple threats achieves meaningful koala conservation outcomes. J. Appl. Ecol. 55, 1966–1975. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13127 (2018).

Polkinghorne, A., Hanger, J. & Timms, P. Recent advances in understanding the biology, epidemiology and control of chlamydial infections in koalas. Vet. Microbiol. 165, 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.02.026 (2013).

Higgins, D. P., Hemsley, S. & Canfield, P. J. Association of uterine and salpingeal fibrosis with chlamydial hsp60 and hsp10 antigen-specific antibodies in Chlamydia-infected koalas. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12, 632–639. https://doi.org/10.1128/CDLI.12.5.632-639.2005 (2005).

Obendorf, D. L. & Handasyde, K. A. Pathology of chlamydial infection in the reproductive tract of the female koala in Biology of the koala (ed. Lee, A. K., Handasyde, K. A. & Sanson, G. D.) 255–259 (Surrey Beatty and Sons, 1990).

Pagliarani, S., Johnston, S. D., Beagley, K. W., Hulse, L. & Palmieri, C. Chlamydiosis and cystic dilatation of the ovarian bursa in the female koala (Phascolarctos cinereus): Novel insights into the pathogenesis and mechanisms of formation. Theriogenology 189, 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.06.022 (2022).

Quigley, B. L., Carver, S., Hanger, J., Vidgen, M. E. & Timms, P. The relative contribution of causal factors in the transition from infection to clinical chlamydial disease. Sci. Rep. 8, 8893. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27253-z (2018).

Robbins, A., Hanger, J., Jelocnik, M., Quigley, B. L. & Timms, P. Longitudinal study of wild koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) reveals chlamydial disease progression in two thirds of infected animals. Sci. Rep. 9, 13194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49382-9 (2019).

Wan, C. et al. Using quantitative polymerase chain reaction to correlate Chlamydia pecorum infectious load with ocular, urinary and reproductive tract disease in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Aust. Vet. J. 89(409), 412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00827.x (2011).

Nyari, S. et al. Epidemiology of chlamydial infection and disease in a free-ranging koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) population. PLoS One 12, e0190114. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190114 (2017).

Legione, A. R. et al. Koala retrovirus genotyping analyses reveal a low prevalence of KoRV-A in Victorian koalas and an association with clinical disease. J. Med. Microbiol. 66, 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.000416 (2017).

Waugh, C. A. et al. Infection with koala retrovirus subgroup B (KoRV-B), but not KoRV-A, is associated with chlamydial disease in free-ranging koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Sci. Rep. 7, 134. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00137-4 (2017).

Holling, T. M., Schooten, E. & van Den Elsen, P. J. Function and regulation of MHC class II molecules in T-lymphocytes: of mice and men. Hum. Immunol. 65, 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2004.01.005 (2004).

Piertney, S. B. & Oliver, M. K. The evolutionary ecology of the major histocompatibility complex. Heredity 96, 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800724 (2006).

Sommer, S. The importance of immune gene variability (MHC) in evolutionary ecology and conservation. Front. Zool. 2, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-2-16 (2005).

Cohen, C. R. et al. Immunogenetic correlates for Chlamydia trachomatis–Associated tubal infertility. Obstet. Gynecol. 101, 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-7844(02)03077-6 (2003).

Morrison, R. P., Feilzer, K. & Tumas, D. B. Gene knockout mice establish a primary protective role for major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted responses in Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. Infect. Immun. 63, 4661–4668. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.63.12.4661-4668.1995 (1995).

Ness, R. B., Brunham, R. C., Shen, C. & Bass, D. C. Associations among human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II DQ variants, bacterial sexually transmitted diseases, endometritis, and fertility among women with clinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex. Transm. Dis. 31, 301–304. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.olq.0000123649.52033.75 (2004).

Brown, J. H. et al. Three-dimensional structure of the human class II histocompatibility antigen HLA-DR1. Nature 364, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/364033a0 (1993).

Belov, K., Lam, M.K.-P. & Colgan, D. J. Marsupial MHC class II β genes are not orthologous to the Eutherian β gene families. J. Hered. 95, 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esh049 (2004).

Lau, Q., Jobbins, S. E., Belov, K. & Higgins, D. P. Characterisation of four major histocompatibility complex class II genes of the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Immunogenetics 65, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00251-012-0658-5 (2013).

Johnson, R. N. et al. Adaptation and conservation insights from the koala genome. Nat. Genet. 50, 1102–1111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0153-5 (2018).

Quigley, B. L. & Timms, P. Helping koalas battle disease - Recent advances in Chlamydia and koala retrovirus (KoRV) disease understanding and treatment in koalas. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 44, 583–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuaa024 (2020).

Robbins, A., Hanger, J., Jelocnik, M., Quigley, B. L. & Timms, P. Koala immunogenetics and chlamydial strain type are more directly involved in chlamydial disease progression in koalas from two south east Queensland koala populations than koala retrovirus subtypes. Sci. Rep. 10, 15013. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72050-2 (2020).

Silver, L. W. et al. A targeted approach to investigating immune genes of an iconic Australian marsupial. Mol. Ecol. 31, 3286–3303. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16493 (2022).

Lau, Q., Jaratlerdsiri, W., Griffith, J. E., Gongora, J. & Higgins, D. P. MHC class II diversity of koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) populations across their range. Heredity 113, 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2014.30 (2014).

Lau, Q., Griffith, J. E. & Higgins, D. P. Identification of MHCII variants associated with chlamydial disease in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). PeerJ 2, e443. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.443 (2014).

Lunney D et al Wildlife and Climate Change: Towards robust conservation strategies for Australian fauna. Lunney D, Hutchings (Eds). Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales (USA, 2012).

Fernandez, C. M. et al. Genetic differences in Chlamydia pecorum between neighbouring sub-populations of koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). Vet. Microbiol. 231, 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.02.020 (2019).

Cheng, Y., Grueber, C., Hogg, C. J. & Belov, K. Improved high-throughput MHC typing for non-model species using long-read sequencing. Mol. Ecol. Resour. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13511 (2021).

He, K., Minias, P. & Dunn, P. O. Long-read genome assemblies reveal extraordinary variation in the number and structure of MHC loci in birds. Genome Biol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evaa270 (2020).

Viļuma, A. et al. Genomic structure of the horse major histocompatibility complex class II region resolved using PacBio long-read sequencing technology. Sci. Rep. 7, 45518. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45518 (2017).

Bataille, A. et al. Susceptibility of amphibians to chytridiomycosis is associated with MHC class II conformation. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 282, 20143127. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.3127 (2015).

Narzi, D. et al. Dynamical characterization of two differentially disease associated MHC class I proteins in complex with viral and self-peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 415, 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.021 (2012).

Russi, R. C., Bourdin, E., García, M. I. & Veaute, C. M. I. In silico prediction of T- and B-cell epitopes in PmpD: First step towards to the design of a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine. Biomed. J. 41, 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2018.04.007 (2018).

Theissinger, K. et al. How genomics can help biodiversity conservation. Trends Genet. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2023.01.005 (2023).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 20. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000411. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411 (2020).

McAlpine, C. et al. Conserving koalas: A review of the contrasting regional trends, outlooks and policy challenges. Biol. Conserv. 192, 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.09.020 (2015).

Phillips, S. S. Population Trends and the Koala Conservation Debate. Conservation Biology 14, 650–659 (2000). https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99387.x

Gordon, G. Estimation of the age of the Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus (Marsupialia: Phascolarctidae), from tooth wear and growth. Aust. Mammal. 14, 5. https://doi.org/10.1071/am91001 (1991).

Andrews S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. (2010).http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. Accessed 10 June 2021.

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869 (2016).

Zhang, Z., Schwartz, S., Wagner, L. & Miller, W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J. Comput. Biol. 7, 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1089/10665270050081478 (2000).

Jobbins, S. E. et al. Diversity of MHC class II DAB1 in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Aust. J. Zool. https://doi.org/10.1071/zo12013 (2012).

Meirmans, P. G. genodive version 3.0: Easy-to-use software for the analysis of genetic data of diploids and polyploids. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20, 1126–1131. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13145 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Sample collection was funded by the Australian Research Council and the project was funded by the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment through the Koala Research Strategy and by Wildlife Information Rescue and Education Service NSW (WIRES). The authors would like to thank all involved in sample and data collection, especially Mathew Crowther, Valentina Mella, Claire McArthur, Cristina Fernandez, Rob Frend, Sam Cliff, George Madani, Martina Zanin and the several volunteers that gave up their time. The authors also thank the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics (University of New South Wales, Australia) for Illumina deep-sequencing of samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. and A.C. performed PCR and confirmed amplification through gel electrophoresis. A.K. performed bioinformatic, statistical analysis and interpretation of results with continued guidance from B.W. Manuscript was written by A.K. with inputs and recommendations from all authors. D.H. and M.K. designed and oversaw the entirety of the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kidd, A., Casteriano, A., Krockenberger, M.B. et al. Koala MHCII association with chlamydia infertility remains equivocal: a need for new research approaches. Sci Rep 14, 31074 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82217-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82217-w