Abstract

We compared the force–velocity (F–V) characteristics between jump squat (JS) and weightlifting (hang clean [HC] and HC pull [HCP]) to determine lower limb F−V portions targeted by weightlifting exercises. Ten weightlifters performed JS at 0% (body weight only) to 70% of their one-repetition maximum (1RM) for back squat, and HC and HCP at 30‒90% and 30‒110% of their 1RM for HC, respectively. Force and velocity values at each relative load were plotted to determine the F–V features of JS, HC, and HCP. Linear regression was used to evaluate each participant’s JS F–V results to obtain individual F–V relationships. Regression equations evaluated the JS force at a given velocity for each relative load of HC and HCP. HC produced significantly less force than JS at given velocities for 30%, 40%, and 50% 1RM. Furthermore, HCP produced significantly less force than JS at a given velocity for 30% 1RM and exhibited less force than JS at a given velocity for 40% 1RM with moderate effect size. HC and HCP produce comparable forces to JS within the velocity ranges of 60‒90% and 50‒110% 1RM, respectively. Thus, weightlifting exercises target low‒moderate-velocity portion of the lower limb F–V relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several sports require motor skills, including high-speed body movements, shoving, and physical control of the opponent. Even simple straight sprinting requires high force output capacities under different velocity conditions, such as the acceleration and maximal velocity phases1,2. Training adaptations, such as strength/power gains, are greatest at or near the training velocity, also known as velocity specificity3,4. Therefore, optimal physical training should target the force–velocity (F–V) relationship portion that corresponds to the physical and sporting demands of each athlete5,6,7,8,9.

The F–V relationship shows an inverse relationship between force and velocity; the lower limb exhibits a linear F–V relationship compared with the individual muscles that exhibit the F–V curve10. The lower limb F–V relationship is typically derived from jump squat (JS) by applying linear regression to the force and velocity outputs across various loads. Because of its ballistic nature, with the external load and lifter’s body leaving the ground at the end of the propulsion phase, JS enables leg extension with maximal effort at any given load11,12. JS is also used as a highly effective exercise for enhancing F–V relationship, as it produces high power across a wide range of loads5,13,14. Similar to JS, weightlifting exercises are considered effective for lower limb resistance exercises15,16,17. Weightlifting is classified into catching exercises that include the phase of catching the bar (e.g., hang clean [HC]) and pulling exercises that eliminate the catching phase (e.g., hang clean pull [HCP]). These variations produce more power than other traditional resistance exercises, and athletes in various sports engage in weightlifting for power development18,19,20. However, as only the external load is projected in weightlifting, the lifter hardly leaves the ground. Therefore, it is considered a semiballistic exercise5,21. The power produced at lighter loads is submaximal22 and may address only limited portions of the lower limb F–V relationship.

Cormie et al.23 compared the power output at different relative loads (percentage one-repetition maximum [RM]) between JS and power clean (a weightlifting catching exercise). They found that power clean produces less power than JS at lighter loads; however, both are comparable at heavier loads, thereby indicating that power clean is effective for enhancing the power output under high-load conditions. Even with comparable power values, the ratio of the components, such as force and velocity, may differ from each other (e.g., force-biased vs. velocity-biased). Considering the velocity specificity of training adaptation3,4, power comparisons at each relative load cannot define the specific portion of the F–V relationship that could be effectively targeted by the power clean. The effectiveness of weightlifting exercises in F–V relationship enhancement requires elucidation of overlap between force and velocity outputs of weightlifting exercises with the lower limb F–V relationship made with JS across an entire loading spectrum (i.e., a comparison of F–V characteristics).

As indicated previously, systematic training combining both catching and pulling variations can enhance the entire F–V relationship16. Pulling exercises such as HCP produce more power than catching exercises such as HC at lighter loads24,25,26, and both variations are required for a comprehensive evaluation of the potential effectiveness of weightlifting exercises. Therefore, this study compared the F–V characteristics between JS and weightlifting exercises (HC and HCP). We hypothesized that due to their semiballistic nature, HC and HCP produce a lower force than JS in the higher-velocity portion of the F–V relationship at lighter loads, while they generate a comparable force in the low–moderate-velocity region of the F–V relationship at moderate-to-heavy loads. Thus, weightlifting exercises may specifically address a low-to-moderate-velocity portion in the lower limb F–V relationship.

Methods

Participants

In total, 12 male competitive weightlifters were included in this study. Two participants were excluded due to injury and/or discomfort; finally, 10 participants were included in the analysis (mean ± SD; age, 20 ± 1 years; height, 169.4 ± 4.9 cm; body mass, 81.3 ± 12.2 kg; competitive experience, 6.8 ± 3.9 years; 1RM back squat, 2.5 ± 0.3 kg·body mass‒1). To determine the correct kinetic characteristics, it was necessary to use participants who were proficient with these movements, as weightlifting movements are hard to perform with correct techniques, particularly at near-maximal loads for non-weightlifters (e.g., track and field athletes)24,26. Therefore, weightlifters who were competing at national and international levels were selected. They performed weightlifting-related training, including HC, HCP, and back squats, five times per week.

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee on Human Research of Waseda University (2022-093), Saitama, Japan. All procedures were performed per the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant for study participation and the publication of identifying information or images in an online, open-access publication.

Test procedures

Data collection took place over 4 days with the 1RM test of HC performed on day 1 and the F–V characteristics were measured on days 2–4. F–V characteristics of JS, HC, and HCP were measured in counterbalanced order, and each session was separated by more than 1 day. Data collection began immediately after participants participated in a weightlifting competition. Relative loads adopted in this study were determined via a preliminary experiment by a weightlifting coach with a training certification from the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). The widest possible range of loads that could be performed correctly and safely by the participants were selected for each exercise: 0‒70% 1RM of the back squat for JS, 30‒90% 1RM of squat HC for HC, and 30‒110% 1RM of squat HC for HCP. HC was categorized into power and squat variations depending on the catching position. HC and HCP loads were determined based on the 1RM of squat HC, which is one of the maximal loads that could be lifted among weightlifting exercises due to its lower catching position compared with power variations (e.g., power HC; Fig. 1). This revealed the maximal (or full) range of the F–V relationship effectively targeted by weightlifting exercises.

1RM test of squat hang clean

All participants refrained from strenuous exercise for at least 24 h before the 1RM test of squat HC. A 10-min dynamic warm-up and HC with light-to-moderate loads (20–60 kg) were performed before the test began. Because the participants were competitive weightlifters, load increments and rest periods were determined arbitrarily, as per their normal practice sessions. HC was performed as previously described24,25,27. Briefly, (1) the participants stood still for a few seconds while holding the bar at their upper thighs, (2) lowered the bar down to the upper borders of their knees, (3) pulled the bar drastically upward with countermovement, and (4) then lowered them into a squat position to catch the bar on their shoulders (Fig. 1). The highest load with which the participant successfully caught the bar in the full squat position was considered the squat HC 1RM. If the bar failed to rest on the shoulders or if it rested but was immediately dropped because of loss of control, the attempt was deemed unsuccessful. The measurement was terminated if the lifts were unsuccessful or if the participants felt at risk of injury. Belts, lifting straps, tapes, and knee sleeves were used throughout the 4-day data collection period.

Hang clean and hang clean pull

Each participant’s body weight and height were measured (height was measured only during the first session) upon arrival at the experimental site. The testing loads for HC and HCP were determined based on each participant’s squat HC 1RM measured on day 1: 30‒90% 1RM and 30‒110% 1RM for HC and HCP, respectively. HC was performed in the similar manner as the 1RM testing session. For HCP, each participant lifted the bar upward as high as possible with countermovement and bending elbows, similar to HC but without subsequent catching24,25,27 (Fig. 2). All participants were cautioned to perform the catching movement at the natural and highest possible position in HC, and to raise the bar as high up as possible to chin height and to refrain from excessive arm use to lift the bar upward in HCP.

At lighter loads, participants performed power HC with a high catching position and shifted to a squat HC with a low catching position with the increased loads. After a standardized warm-up, all participants performed specific HC or HCP warm-ups with 5 repetitions at 20 kg, 3 at 30% 1RM, and 2 at 50% 1RM. Data were collected using 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, and 90% 1RM for HC or 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 100%, and 110% 1RM for HCP. In HC and HCP, participants made two attempts at each load from 30 to 70% 1RM and one attempt at each load ≥ 80% 1RM to prevent excessive fatigue and execute movements correctly. The resting periods were 2 min between the attempts and 3 min between loads. Loads were gradually increased from light loads to heavy ones for safety and movement accuracy.

Jump squat

After physical measurements, the 1RM of the participants’ back squat within a month before data collection was obtained by interview. The back squat was performed by a full squat in the deeper bottom position, which is frequently performed than the half squat. The tested relative JS loads were determined based on each participant’s back squat 1RM such as 0‒70% 1RM. To control the depth of JS, the height of the lower buttocks from the ground at 90° of the knee joint was measured for each participant, and photocell beam sensor (FMT-1P1, 4Assist, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was placed at the height for all trials.

Lifter© (Intelligent Motion Gmbh, Linz, Austria) was used to moderate the high impact at landing in JS. This tool consists of movable safety arms positioned on both sides that support the bar and a cable suspended from the top that detects bar movement by attaching it to the bar end. The weightlifting bar was initially supported on safety arms at chest height. As the participant put the bar on the upper trapezius and stood up, the safety arms simultaneously lowered to approximately waist height to prevent contact with the bar. The participants then jumped vertically using countermovement with maximal effort (Fig. 3). The safety arms elevated as weights were lifted upward and stopped at set heights to block weight descent and allow each participant to land with their bodies alone. All participants were instructed to initiate the JS movements after standing still with weights for a few seconds and not to let the bar lift off the upper trapezius until they reached their maximal height. After a standard 5-min warm-up, all participants performed specific warm-ups for JS: 5 and 3 repetitions at 20 kg and 20% 1RM for JS, respectively. Next, the participants performed JS using Lifter© at 0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, and 70% 1RM with two attempts at each load. The depth of descent for JS was defined by the photocell beam sensor. A participant made another attempt when the depth was found to be either too shallow or too deep. There was a 2-min resting period between attempts and a 3-min resting period between loads. A very light wooden stick was used for the attempt at 0% 1RM to mimic the posture of holding the weightlifting bar. Similar to HC and HCP, loads were gradually increased from light to heavy.

Data analysis

All data were collected on a force platform (type 9281E, Kistler, Winterthur, Switzerland) to obtain vertical ground reaction data. Subsequently, analog data were converted to digital data at 1,000 Hz using an analog-to-digital converter (PowerLab, ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia) and recorded using data acquisition and analysis software (LabChart ver. 8, ADInstruments).

The system (lifter’s body mass + external load) velocity was calculated from the force data on the software using forward dynamics. Integration initiation, i.e., the beginning of movement after a stationary state, was determined as 30 ms before the instant when the ground reaction force exceeds system weight ± 5 SD28. Power was calculated by multiplying the F and V values at each time interval. Peak power was defined as the highest value observed during the propulsive phase, and the force at peak power (Fpp) and velocity at peak power (Vpp) were recorded when peak power was produced29,30. For each participant, relative value (rFpp) was calculated using Fpp/body mass. For loads with data for two attempts, 0‒70% JS and 30‒70% HC and HCP 1RMs, the attempt that generated the highest peak power was used for analyses.

The average values of rFpp and Vpp at each relative load were plotted to create F–V characteristics of JS, HC, and HCP. Linear regression was applied to each participant’s JS F–V relationship to obtain individual lower limb F–V relationships. From the regression equations (y = ax + b), the estimated rFpp values of JS were calculated for each participant at a given Vpp of each relative load of HC and HCP, which allowed direct comparison of force outputs between JS and weightlifting exercises at given velocities across a loading spectrum. The relative intensities (%) of rFpp of HC and HCP to the estimated rFpp of JS were calculated.

Subsequently, a digital camera (DMC-FZ300, Panasonic, Osaka, Japan) was used at 240 Hz to record HC attempts from a sagittal plane for two-dimensional video analyses to differentiate between power HC and squat HC. A motion analysis software program (Kinovea version 0.9.5) was used to measure the knee angle (the smallest angle formed by the position data of the greater trochanter, lateral epicondyle of the femur, and lateral malleolus) for the catching position of HC. The position data for each joint were manually plotted. HC was classified into power HC (i.e., quarter squat) or squat HC (i.e., below quarter squat) depending on the catching position31. In the current study, participants were instructed to perform the catching movements at the highest possible position; therefore, they did power HC till a certain load and then shifted to squat HC as the load was increased. The heaviest 1RM load of squat HC caught above the quarter squat position (knee angle > 110°) was considered as power HC 1RM32.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel ver. 2310 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS Statistics ver. 28 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). Data normality was analyzed for Fpp and Vpp using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The test–retest reliability of Fpp and Vpp among repetitions was verified for loads with data for two attempts, 0–70% JS and 30–70% HC and HCP 1RMs. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs [1,1]) were calculated when data normality was confirmed, and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used when normality was not verified. The coefficient of variation (CV) was also analyzed to assess reliability. The correlation strength was interpreted as poor (< 0.50), moderate (0.50–0.74), good (0.75–0.89), or excellent (≥ 0.90)33. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) assessed the relationship between rFpp and Vpp in JS for each participant. The two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare rFpp between JS and HC and between JS and HCP at a Vpp of different relative loads. Partial η2 was reported to show the effect size of the ANOVA tests. Bonferroni’s correction was used for paired comparisons between values of each exercise at the Vpp of each load. The bias-corrected Hedges’ g was calculated to report practical differences34 and interpreted as follows: <0.20 (trivial), 0.20–0.59 (small), 0.60–1.19 (moderate), 1.20–1.99 (large), 2.00–3.99 (very large), and ≥ 4.00 (extremely large)35. Data were expressed as the mean ± SD. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The normality of all data was verified (p > 0.05) except for Vpp in the first attempt of 50% 1RM of HC (p = 0.009). The ICCs of Fpp for loads with data for two attempts showed good reliability for 30% and 50%1RM of HCP (ICCs = 0.861, 0.873), and showed excellent reliability for other tested loads (ICCs = 0.924‒0.987). The ICCs of Vpp showed good reliability for 20% 1RM of JS, 70% 1RM of HC, and 50% and 60% 1RM of HCP (ICCs = 0.786‒0.892) and showed excellent reliability for other tested loads (ICCs = 0.907‒0.979). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of Vpp for 50% 1RM of HC was 0.818, indicating good reliability. The CV of Fpp and Vpp for all loads with two attempts were 0.03‒1.72% and 0.21‒1.50%, respectively.

The 1RM of the back squat, squat HC, and power HC were 200.2 ± 34.0, 147.0 ± 15.0, and 87.4 ± 11.2 kg, respectively (2.5 ± 0.3, 1.8 ± 0.3, and 1.1 ± 0.2 kg·body mass‒1, respectively). Additionally, the power HC 1RM was 60% ± 9% squat HC 1RM.

Comparison of F–Vcharacteristics between exercises

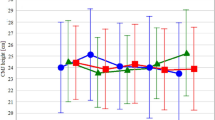

The F–V characteristics (average rFpp and Vpp at each relative load of JS, HC, and HCP) are shown in Fig. 4. The dashed line represents the lower limb F–V relationship (y = − 14.051x + 56.608), as shown by the linear regression line. Pearson’s correlation coefficient of each participant’s F–V relationship with JS data showed very strong negative correlations (r = 0.971–0.999).

Comparison of F–V characteristics obtained from averaged values of rFpp and Vpp at each relative load of JS, HC, and HCP. The dashed line represents the lower limb F–V relationship, shown with linear regression. F–V force–velocity, rFpp relative force at peak power, Vpp velocity at peak power, JS jump squat, HC hang clean, HCP hang clean pull.

The two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used for comparisons between JS and HC. A significant interaction was observed in rFpp between exercises and Vpp (p = < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.778; Fig. 5). Paired comparisons with Bonferroni’s correction showed significant differences in rFpp between JS and HC at Vpp values for loads of 30%, 40%, and 50% 1RM (p < 0.001, = 0.004, and = 0.032, respectively). The effect sizes of the differences (Hedges’ g) were 2.17, 1.40, 0.83, 0.41, 0.23, 0.22, and 0.36 at Vpp load values of 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, and 90% 1RM, respectively. The relative intensity (%) of HC rFpp compared with JS rFpp were 78% ± 12%, 86% ± 12%, 92% ± 11%, 96% ± 8%, 98% ± 7%, 98% ± 7%, and 97% ± 7% at Vpp of 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, and 90% 1RM, respectively.

Comparison of rFpp between JS and HC at a given Vpp of different HC loads (% 1RM). The dashed line represents the lower limb F–V relationship. The numbers within the red circles represent HC loads (%1RM). *P ≤ 0.05 between JS and HC. rFpp relative force at peak power, Vpp velocity at peak power, JS jump squat, HC hang clean, F–V force–velocity.

There was also a significant rFpp–Vpp interaction between JS and HCP (p = < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.449). Figure 6 shows significant differences in rFpp between JS and HCP at Vpp values for 30% 1RM loads (p = 0.015), and HCP produced a lower rFpp than JS at a Vpp of 40% 1RM with a moderate effect size. The effect sizes of the differences were 1.13, 0.60, 0.22, 0.07, 0.02, 0.25, 0.25, 0.37, and 0.58 at Vpp of 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 100%, and 110% 1RM, respectively. The relative intensity (%) of HCP rFpp to JS rFpp were 87% ± 14%, 94% ± 12%, 98% ± 9%, 99% ± 9%, 100% ± 7%, 98% ± 9%, 98% ± 9%, 97% ± 7%, and 94% ± 9% at Vpp of 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 100%, and 110% 1RM, respectively.

Comparison of rFpp between JS and HCP at a given Vpp of different HCP loads (% 1RM). The dashed line represents the lower limb F–V relationship. The numbers within the green circles represent HCP loads (%1RM). *P ≤ 0.05 between JS and HCP. rFpp relative force at peak power, Vpp velocity at peak power, JS jump squat, HCP hang clean pull, F–V force–velocity.

Figure 7 shows the entire F–V relationship (dashed line) and specific F–V regions effectively targeted by JS, HC, and HCP based on the results from Figs. 4, 5 and 6. The areas targeted by JS were selected assuming that 40% 1RM (approximately 80 kg on average for the subjects in this study) is the maximum weight that could be safely landed without special equipment to modify high impact upon landing. Previous training studies used JS loads in the range of 0–40% 1RM36,37,38.

Entire F–V relationship (dashed line). Specific F–V regions effectively targeted by JS, HC, and HCP are shown using blue, red, and green lines, respectively. The green area is where JS can safely target assuming that 40% 1RM is the maximal feasible weight that can be safely landed with. F–V force–velocity, JS jump squat, HC hang clean, HCP hang clean pull.

Discussion

This study compared the F–V characteristics of HC and HCP with that of JS to determine the F–V portions effectively targeted by weightlifting exercises. HC produced a significantly lower rFpp than JS at the Vpp values for 30‒50% 1RM (Fig. 5). In addition, HCP produced a significantly lower rFpp than JS at the Vpp of 30% 1RM and tended to show a lower rFpp than JS at the Vpp values for 40% 1RM with a moderate effect size (Fig. 6). These results support our hypothesis that HC and HCP produce a comparable force as JS at velocity portions for moderate‒heavy loads, which indicates that weightlifting exercises specifically target the low‒moderate-velocity portions of the lower limb F–V relationship (Fig. 7).

A lower rFpp in HC than that in JS at 30‒50% 1RM (moderate-to-very large effect; relative intensity of 78–92%) appeared due to a limitation in the height of the lifted bar because of catching movements. At lighter loads, lifters need to perform HC with submaximal efforts to keep the bar from being lifted above the height limit22,26, possibly leading to a low rFpp value for a load at 30‒50% 1RM. In addition, HCP produces lower rFpp than JS at a Vpp value for loads of 30‒40% 1RM (moderate effect; relative intensity of 87–94%). The height limit for pulling exercises, such as HCP, is relatively greater than that for catching exercises because of the absence of catching movements26. However, it is not without limits, like JS, when the external load and the lifter’s body leave the ground. Therefore, performing HCP with maximal effort under too light loads, such as at 30‒40% 1RM, is not possible. From a mechanical perspective, the system velocity at lighter loads is constrained by the limits of the bar height22,26 and should be equivalent at 30‒50% 1RM for HC and 30‒40% 1RM for HCP; however, our results are contrary. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the lifters were not accustomed to perform weightlifting with maximal intent with very light loads and may have excessively limited their force and velocity outputs, contrary to the given instructions. These results do not differ from our hypothesis; rather, they indicate that weightlifting exercises cannot be performed at maximal effort with light loads, which produce less force than JS in the higher-velocity region.

These movement characteristics indicate that sufficiently heavy loads are required for lifters to accomplish HC and HCP with maximal effort. HC and HCP produce a comparable force to JS at 60‒90% and 50‒110% 1RM, respectively, with only trivial-to-small effect sizes (relative intensity ≥ 94%). Thus, weightlifting exercises effectively target a low-to-moderate-velocity region of the F–V relationship. HCP can cover a wider velocity range than HC because of the absence of catching movements. Lifters can lift the bar higher in HCP than in HC with lighter loads and can also work with loads greater than HC 1RM16,39,40 (Fig. 7).

JS is relatively easy to learn; therefore, using JS with various loads is recommended for effectively improving the lower limb F–V relationship13,36,41. However, high impacts at landing with heavy loads has a high injury risk, and electromagnetic braking systems or special training machines that were developed to modify high impacts should be used for injury prevention42,43,44. In contrast, weightlifting exercises can be performed with heavy loads while avoiding an excessive landing impact42,45. Therefore, in absence of special equipment, which is a typical case for coaches and athletes, performing JS using lighter loads (0‒40% 1RM) can be a safe and effective training technique for targeting high-velocity regions. Previous training intervention studies have used JS loads in the 0–40% 1RM range36,37,38. In contrast, HC and HCP using moderate-to-heavy loads (≥ 60% and ≥ 50% 1RMs, respectively) can be performed when targeting a low‒moderate-velocity region of the lower limb F–V relationship (Fig. 7). Therefore, coaches and athletes should understand the advantages and disadvantages of JS and weightlifting exercises, and select the appropriate combination of exercise and load as per the demands of their sports.

The success criteria for the catching position greatly alter the 1RM and relative loads (% 1RM) of weightlifting exercises. In the current study, the relative loads for HC and HCP were determined based on the 1RM of squat HC, which requires a deep catching position (full squat). However, power HC, which uses a high catching position (quarter squat), is relatively easy to perform and widely used by athletes for power training, although the loads that can be lifted are low46,47. Therefore, many coaches and athletes might benefit from recommended loads based on power HC 1RM. The findings of this study reveal that power HC 1RM was 60 ± 9% 1RM of squat HC 1RM. Considering the lightest effective loads of HC being 60% 1RM of squat HC (Fig. 5), power HC should be performed with maximal load (i.e., 100% 1RM). This notion is supported by the fact that the load producing the maximal power in power HC is the 1RM when the success criterion is set at the quarter squat position22. The HCP loads effectively targeting the F–V relationship were ≥ 50% 1RM based on squat HC 1RM (Fig. 6). In contrast, effective loads for HCP reached ≥ 83% 1RM when calculated based on power HC 1RM. Therefore, it is necessary to set criteria (full squat vs. quarter squat) for appropriate load prescriptions.

This study has a few limitations. First, all participants were weightlifters, and the sample size was relatively small because of the difficulty in obtaining good-quality samples. As a result, the findings may not be directly applicable to athletes involved in other sports. However, inclusion of these participants was appropriate for assessing the correct kinetic characteristics, as they had sufficient experience and proficiency in weightlifting exercises (competitive experience = 6.8 ± 3.9 years and 1RM squat HC = 1.8 ± 0.3 kg·body mass‒1). Second, the relative loads for JS were not precise as they were based on full-squat 1RM instead of half-squat 1RM, although JS was performed approximately at a half-squat depth. However, an NSCA-certified coach determined the widest load range that the participants could perform safely and correctly for JS, and the F–V range effectively targeted by JS was successfully determined. Therefore, differences in measuring back squat 1RM did not affect the results. Third, HC and HCP were selected as representative weightlifting exercises, while other variations, such as Snatch, can demonstrate slightly different F–V characteristics (e.g., more velocity bias). However, weightlifting exercises share common characteristics, such as a height limit for bar lifting; therefore, exercise selection does not significantly affect the results. Fourth, because the system’s (barbell + body) center of mass constantly shifts during movement, the system velocity and force used to create the F–V relationship may not strictly represent the mechanical conditions experienced by the lower limbs. However, this does not appear to affect our conclusions, which are based on the comparison between exercises. Furthermore, although there may have been some upper limb involvement in HC and HCP resulting in F–V outputs that were not purely reflective of the lower limbs, the participants’ expertise suggests that excessive use of the arms (i.e., early arm bend) was likely minimal. Fifth, this was a cross-sectional study and therefore, we were unable to verify the effects of actual training on weightlifting exercises. Therefore, a long-term prospective interventional study is required.

In conclusion, HC and HCP produce a force comparable with that of JS within velocity ranges for moderate-to-heavy loads (60‒90% 1RM and 50‒110% 1RM, respectively). Therefore, weightlifting exercises specifically target a low‒moderate-velocity portion in an athlete’s lower limb F–V relationship, and weightlifting pulling (e.g., HCP) can address a wider F–V region than the catching variation (e.g., HC).

Data availability

The data generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hicks, D. S., Schuster, J. G., Samozino, P. & Morin, J. B. Improving mechanical effectiveness during sprint acceleration: practical recommendations and guidelines. Strength Cond. J. 42, 45–62 (2020).

Morin, J. B., Samozino, P., Bonnefoy, R., Edouard, P. & Belli, A. Direct measurement of power during one single sprint on treadmill. J. Biomech. 43, 1970–1975 (2010).

Cormie, P., McGuigan, M. R. & Newton, R. U. Influence of strength on magnitude and mechanisms of adaptation to power training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 42, 1566–1581 (2010).

Kawamori, N. & Newton, R. U. Velocity specificity of resistance training: actual movement velocity versus intention to move explosively. Strength Cond. J. 28, 86 (2006).

Cormie, P., McGuigan, M. R. & Newton, R. U. Developing maximal neuromuscular power: part 2-training considerations for improving maximal power production. Sports Med. 41, 125–146 (2011).

Newton, R. U. & Kraemer, W. J. Developing explosive muscular power: implications for a mixed methods training strategy. Strength Cond. J. 16, 20–31 (1994).

Haff, G. G. & Nimphius, S. Training principles for power. Strength Cond. J. 34, 2–12 (2012).

Turner, A. N. et al. Developing powerful athletes, part 1: mechanical underpinnings. Strength Cond. J. 42, 30–39 (2020).

Turner, A. N. et al. Developing powerful athletes, part 2: practical applications. Strength Cond. J. 43, 23–31 (2021).

Jaric, S. Force-velocity relationship of muscles performing multi-joint maximum performance tasks. Int. J. Sports Med. 36, 699–704 (2015).

Samozino, P., Morin, J. B., Hintzy, F. & Belli, A. Jumping ability: a theoretical integrative approach. J. Theor. Biol. 264, 11–18 (2010).

Giroux, C., Rabita, G., Chollet, D. & Guilhem, G. What is the best method for assessing lower limb force-velocity relationship? Int. J. Sports Med. 36, 143–149 (2015).

Newton, R. U., Kraemer, W. J. & Häkkinen, K. Effects of ballistic training on preseason preparation of elite volleyball players. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 31, 323–330 (1999).

McBride, J. M., Triplett-McBride, T., Davie, A. & Newton, R. U. The effect of heavy- vs. light-load jump squats on the development of strength, power, and speed. J. Strength Cond. Res. 16, 75–82 (2002).

Soriano, M. A., Jiménez-Reyes, P., Rhea, M. R. & Marín, P. J. The optimal load for maximal power production during lower-body resistance exercises: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 45, 1191–1205 (2015).

Suchomel, T. J., Comfort, P. & Lake, J. P. Enhancing the force-velocity profile of athletes using weightlifting derivatives. Strength Cond. J. 39, 10–20 (2017).

Suchomel, T. J., Comfort, P. & Stone, M. H. Weightlifting pulling derivatives: rationale for implementation and application. Sports Med. 45, 823–839 (2015).

Simenz, C. J., Dugan, C. A. & Ebben, W. P. Strength and conditioning practices of National Basketball Association strength and conditioning coaches. J. Strength Cond. Res. 19, 495–504 (2005).

Ebben, W. P., Carroll, R. M. & Simenz, C. J. Strength and conditioning practices of National Hockey League strength and conditioning coaches. J. Strength Cond. Res. 18, 889–897 (2004).

Jones, T. W., Smith, A., Macnaughton, L. S. & French, D. N. Strength and conditioning and concurrent training practices in elite rugby union. J. Strength Cond. Res. 30, 3354–3366 (2016).

Moir, G. Training methods to develop muscular strength and power. In Strength and Conditioning: A Biomechanical Approach, 235–286 (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2015).

Takei, S., Hirayama, K. & Okada, J. Is the optimal load for maximal power output during hang power cleans submaximal? Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 15, 18–24 (2020).

Cormie, P., McCaulley, G. O., Triplett, N. T. & McBride, J. M. Optimal loading for maximal power output during lower-body resistance exercises. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 39, 340–349 (2007).

Suchomel, T. J., Wright, G. A., Kernozek, T. W. & Kline, D. E. Kinetic comparison of the power development between power clean variations. J. Strength Cond. Res. 28, 350–360 (2014).

Suchomel, T. J. & Sole, C. J. Power-time curve comparison between weightlifting derivatives. J. Sports Sci. Med. 16, 407–413 (2017).

Takei, S., Hirayama, K. & Okada, J. Comparison of the power output between the hang power clean and hang high pull across a wide range of loads in weightlifters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 1, S84–S88 (2021).

Suchomel, T. J. & Sole, C. J. Force-time-curve comparison between weight-lifting derivatives. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 12, 431–439 (2017).

Owen, N. J., Watkins, J., Kilduff, L. P., Bevan, H. R. & Bennett, M. A. Development of a criterion method to determine peak mechanical power output in a countermovement jump. J. Strength Cond. Res. 28, 1552–1558 (2014).

Suchomel, T. J. et al. The effect of load placement on the power production characteristics of three lower extremity jumping exercises. J. Hum. Kinet. 68, 109–122 (2019).

Suchomel, T., McKeever, S., Nolen, J. & Comfort, P. Muscle architectural and force-velocity curve adaptations following 10 weeks of training with weightlifting catching and pulling derivatives. J. Sports Sci. Med. 21, 112–119 (2022).

Caulfield, S. & Berninger, D. Exercise technique for free weight and machine training. In Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning (eds Haff, G. & Triplett, N.), 351–408 (Human Kinetics, 2015).

Schoenfeld, B. J. Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 24, 3497–3506 (2010).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163 (2016).

Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 4, 863 (2013).

Hopkins, W. G., Marshall, S. W., Batterham, A. M. & Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41, 3–13 (2009).

Cormie, P., McCaulley, G. O. & McBride, J. M. Power versus strength-power jump squat training: influence on the load-power relationship. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 39, 996–1003 (2007).

Cormie, P., McGuigan, M. R. & Newton, R. U. Adaptations in athletic performance after ballistic power versus strength training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 42, 1582–1598 (2010).

Oranchuk, D. J., Robinson, T. L., Switaj, Z. J. & Drinkwater, E. J. Comparison of the hang high pull and loaded jump squat for the development of vertical jump and isometric force-time characteristics. J. Strength Cond. Res. 33, 17–24 (2019).

Suchomel, T. J., McKeever, S. M. & Comfort, P. Training with weightlifting derivatives: the effects of force and velocity overload stimuli. J. Strength Cond. Res. 34, 1808–1818 (2020).

Suchomel, T. J., McKeever, S. M., McMahon, J. J. & Comfort, P. The effect of training with weightlifting catching or pulling derivatives on squat jump and countermovement jump force–time adaptations. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 5, 28 (2020).

McBride, J. M., Triplett, N. T., Davie, A. & Newton, R. U. The effect of heavy- vs. light-load jump squats on the development of strength, power, and speed. J. Strength Cond. Res. 16, 75–82 (2002).

Hori, N., Newton, R. U., Nosaka, K. & Stone, M. H. Weightlifting exercises enhance athletic performance that requires high-load speed strength. Strength Cond. J. 24, 50 (2005).

Humphries, B. J., Newton, R. U. & Wilson, G. J. The effect of a braking device in reducing the ground impact forces inherent in plyometric training. Int. J. Sports Med. 16, 129–133 (1995).

Teo, S. Y. M., Newton, M. J., Newton, R. U., Dempsey, A. R. & Fairchild, T. J. Comparing the effectiveness of a short-term vertical jump vs. weightlifting program on athletic power development. J. Strength Cond. Res. 30, 2741–2748 (2016).

Burkhardt, B. & Barton, B. Garhammer. Maximal impact and propulsion forces during jumping and explosive lifting exercises. J. Appl. Sport Sci. Res. 4, 107–114 (1990).

Hori, N. et al. Does performance of hang power clean differentiate performance of jumping, sprinting, and changing of direction? J. Strength Cond. Res. 22, 412–418 (2008).

Ronai, P. & Scibek, E. The hang power clean. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 20, 50–55 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the weightlifting team members of Waseda University for their participation in the study. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP17K01696 and Waseda University Grant for Special Research Projects (project number: 2020C-700).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T., S.K., J.O., and K.H. conceived the idea; S.T., S.K., M.K., and K.H. performed experiments; S.T., S.K., M.K., and K.H. analyzed the data: S.T., S.K., and K.H. interpreted the results; S.T., and S.K. drafted the manuscript; S.T., S.K., M.K., J.O., and K.H. critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takei, S., Kambayashi, S., Katsuge, M. et al. Portions of the force–velocity relationship targeted by weightlifting exercises. Sci Rep 14, 31021 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82251-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82251-8