Abstract

Colobanthus quitensis is known for enduring extreme conditions, such as high salinity in Antarctica, making it an excellent model for studying environmental stress. In plant families, variations in seed color heteromorphism have been linked to various germination under stress conditions. Preliminary laboratory observations indicated that dark brown seeds of C. quitensis had higher germination rates, suggesting that this phenotypic trait might offer a germination advantage, particularly under saline conditions. To investigate this, germination of heteromorphic seeds from Antarctic, sub-Antarctic, and Andean populations of C. quitensis was assessed under in vitro saline conditions. Among all populations, dark brown seeds exhibited greater germination and shorter germination time than other seeds in the absence of salinity. In the Antarctic population, dark brown seeds showed better salinity tolerance. In the sub-Antarctic La Marisma population, salt tolerance was not affect by seed color, showing the population was the most salt-tolerant. The other two populations showed very low germination even at low salinity concentration. This study is the first scientific report of seed heteromorphism in C. quitensis populations, offering insights into mechanisms of salinity tolerance and potentially other stress conditions that enhance the species’ resilience. In addition, the identification of La Marisma populations as a salinity-tolerant population will holds biotechnological importance for agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global climate change contributes to increased soil salinity due to rising sea levels and changing rainfall patterns. This fact negatively affects plant development, especially germination and initial seedling growth1. The osmotic stress caused by salinity decrease germination, plant nutrient uptake, elevate ion toxicity, as well as confer morphological (e.g., reducing root and shoot length, changing root architecture), biochemical (e.g., decreased chlorophyll and carotenoid content, excessive Na+ accumulation, lower K+/Na+ ratio), and physiological changes (e.g., decreasing stomatal conductance, changes in chloroplast structure, lower photosystem II efficiency)2,3,4,5.

During evolution, plants have developed different stress tolerance mechanisms to survive in different environments, including Antarctic and desertic ones. Among them can be mentioned the accumulation of protective osmolytes, scavenging of reactive oxygen species, selective ion uptake, changing root architecture, protection of the photosynthetic system, and reduction of their metabolism and growth6. Also, researchers have identified seed heteromorphism as a survival strategy that helps plants grow and endure in harsh conditions7. In this regard, heteromorphism is evident when a species produces seeds with different morphology, size, weight, and/or color. These characteristics influence seed germination success, dormancy, and vigor7. Studies on the impact of seed heteromorphism on germination often use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to analyze testa microstructure, as color and morphological alterations are sometimes linked8,9. Moreover, heteromorphic seeds in the presence of abiotic stress conditions such as salinity, temperature, and illumination changes show different germination rates10,11. The ratio of one type of heteromorphic seed to another varies with populations, varieties, climatic, and environmental conditions11,12. Then, a greater germination percentage of heteromorphic seeds on certain ecosystem conditions suggest that these seeds have higher adaptability to this environment than other ones. Hence, color heteromorphism may serve as an indicator of the specific stress condition prevailing in each habitat and its impact on the ecological dynamics of plant species13.

Colobanthus quitensis (Kunth) Bartl. is considered a model plant for biotechnological studies and for understanding adaptive mechanisms to extreme environments, as well as an indicator of the effects of climate change in Antarctica14,15. It is an extremophile species distributed from southern Mexico to the north of the Antarctic Peninsula16. Thus, to perform successful scientific research, deep understanding of the physiology and genetics of model plant species17,18, like C. quitensis is crucial. Certain populations of this species are located along the coast19, which exposes them to marine aerosols directly or enables them to grow in soils drenched with saltwater20. Recent studies have categorized C. quitensis as moderately tolerant to salinity, capable of withstanding from 150 mM NaCl in common garden conditions and up to 400 mM NaCl in vitro, showing morphological, physiological, and biochemical adaptations to salinity stress21,22,23. Therefore, throughout the germination process, seeds do not exhibit the same responses or adaptive strategies against salinity as observed in mature plants7. For instance, C. quitensis seeds show a reduction in their germination and seedling survival rates when exposed to salt concentrations exceeding 100 mM NaCl21,22. Therefore, further research is required to distinguish the salinity tolerance of C. quitensis seeds among its populations. Seed stress can affect plant reproduction and productivity24. Then, germination tests are a rapid and effective alternative to detect genotypes resistant to environmental stresses25.

Seed heteromorphism has been previously described in different families such as Fabaceae8, Amaranthaceae11,13, and Caryophyllaceae26, to which C. quitensis belongs. There are several reports that studied the germination process in different populations of C. quitensis27,28,29,30,31, but none have mentioned the presence of heteromorphism or its influence on germination. These studies documented variations in germination rates among C. quitensis populations. These variations may relate to dormancy30, but seed traits likely influenced the results, as dark brown seeds showed higher germination rates.

Whe hypothesized that the color heteromorphism observed in C. quitensis confers plasticity in the response to salinity, which could be influenced by local adaptation acquired by the mother plants. This work aims to answer three research questions: (I) Are there differences in germination among different populations of C. quitensis? (II) Does color heteromorphism influence the germination rate of C. quitensis populations? (III) Does the presence of seeds color heteromorphism in C. quitensis constitute an adaptation mechanism of salinity tolerance? Therefore, the objective of this work was to analyze whether seeds from different populations of C. quitensis, grown under controlled conditions, vary in their tolerance to salinity depending on their color heteromorphism. For this purpose, the morphology of light and dark brown seeds was analyzed for structural differences, as well as in vitro germination analyses of heteromorphic seeds in the presence and absence of salinity.

Results

Electron microscopy analysis

SEM analysis was conducted to ascertain any morphological disparities among C. quitensis seeds of varying colors. According to SEM micrographs, both the light brown and dark brown seeds of C. quitensis populations are triangular and kidney shaped. Furthermore, morphological examination of the seeds reveals a uniform, mostly smooth tegument surface, with the presence of small puzzle-like striations near the micropyle area (Fig. 1). Overall, there were no discernible differences in the seed coat with different colors.

SEM micrographs of heteromorphic Colobanthus quitensis seeds side view. Lateral view of light brown seeds from (a) Arctowski, (b) La Marisma, (c) Laredo and (d) Conguillío populations; and dark brown seeds from (e) Arctowski, (f) La Marisma, (g) Laredo and (h) Conguillío populations. Close-up of the light brown seed micropyle area from (i) Arctowski, (j) La Marisma, (k) Laredo and (l) Conguillío populations; and dark brown seeds from (m) Arctowski, (n) La Marisma, (o) Laredo and (p) Conguillío populations. Yellow arrows indicate the position of the micropile. Red arrow indicates the presence of surface striations.

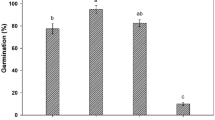

Effect of population on seed germination

In each population, the germination percentage of C. quitensis seeds was over 40% (Fig. 2a). The pPA and pC populations showed the highest germination percentage, 78% and 66%, respectively, with no statistical difference (p < 0.05). Conversely, the germination percentage of pL (41%) and pA (46%) populations were statistically similar (p < 0.05), but 1.9-fold and 1.6-fold lower (p < 0.05) than pPA population.

Germination indicators of different populations of Colobanthus quitensis. (a) Germination and (b) time to reach 50% germination (T50). Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 10). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) according to one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey HSD test.

On the other hand, the time at which 50% germination is reached (T50) was higher than 10 days for all populations (Fig. 2b). A significantly lower T50 (p < 0.05) was observed in pPA (10.8 days) compared to pL (14.48 days) and pC (18.4 days). While the T50 of pA (12.39 days) does not differ statistically (p > 0.05) from the T50 of pPA and pL.

Effect of color heteromorphism on seed germination

Seed color had a significant effect on germination rates (Supplementary Table 1), which was evidenced by the fact that dark brown seeds in all populations had a significantly (p < 0.05) higher germination percentage than light brown seeds (Fig. 3a). The dark seeds of pPA (91%) and pC (84%) achieved the highest germination percentages. It should be noted that light brown seeds of pA and pL barely exceeded 20% germination.

Germination indicators of different populations of Colobanthus quitensis. (a) Germination and (b) time to reach 50% germination (T50) of heteromorphic seeds from Arctowski (pA), La Marisma (pPA), Laredo (pL) and Conguillío populations (pC). Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 5). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) according to one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey HSD test.

Also, the dark brown seeds required significantly (p < 0.05) less time to reach 50% germination than the light ones. From all populations, the light (11.7 days) and dark (9.9 days) pPA seeds reached their T50 faster (Fig. 3b).

Interplay between color heteromorphism and salinity on seed germination

The presence of NaCl salt in the medium affected the germination of all C. quitensis populations, while seed color only showed influence on the germination of pA and pC populations. The interaction of both factors had significant effect (p < 0.05) in germination percentage of all populations except for pC (Supplementary Table 1).

Both light and dark seeds show a general trend of germination percentage decreasing with increasing salinity. When the results were analyzed, we could observe that dark seeds from the pA and pC populations have a higher germination percentage than light seeds. Conversely, for the pPA and PL populations, light seeds tend to have a higher germination percentage than dark brown seeds (Fig. 4).

Germination percentage of heteromorphic seeds of Colobanthus quitensis treated with different concentrations of sodium chloride (50–200 mM). Light and dark brown seeds from (a) Arctowski (pA), (b) La Marisma (pPA), (c) Laredo (pL) and (d) Conguillío populations (pC). Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 5). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) according to factorial analysis (2 × 5), followed by a Tukey HSD test.

The germination percentage of dark brown seeds from pA populations in NaCl 50 mM was the highest (73%), then it decreased to 52% at 100 mM (Fig. 4a). The presence of 50 and 100 mM NaCl did not generate differences in germination between light and dark brown seeds in the pPA population (Fig. 4b). On the other hand, the pL and pC populations showed a higher susceptibility to salt concentrations higher than 150 mM NaCl (Fig. 4c, d).

Salinity in the medium affected the T50 of all populations (Fig. 5), while seed color only influenced the T50 of pL and pC (p < 0.05). The interaction between these factors significantly affected the T50 of pL and pC (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 2).

Time to reach 50% germination (T50) of heteromorphic seeds of Colobanthus quitensis subjected to different concentrations of sodium chloride. Light and dark brown seeds from (a) Arctowski (pA), (b) La Marisma (pPA), (c) Laredo (pL) and (d) Conguillío populations (pC). The bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 75). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) according to factorial analysis (2 × 5), followed by a Tukey HSD test.

The pPA population had the lowest T50 in the presence of 200 mM NaCl for both seed types (14 days), compared to the other populations (Fig. 5b). In contrast, the pC population maintained a high T50 regardless of NaCl concentration. For example, dark seeds took 17 days to reach their T50 under control conditions (0 mM NaCl) and 23 days in the presence of 200 mM NaCl (Fig. 5d).

The cumulative germination analysis indicates that the dark brown seeds of pA (Fig. 6b) and pPA (Fig. 6d) began to germinate faster than their light brown counterparts (Fig. 6a, c). Increasing the salt concentration in the in vitro medium resulted in a decreased germination percentage and an increased germination time. Salinity has the most severe negative effect on the light brown seeds of pA (Fig. 6a), as well as on both seed colors of the pL (Fig. 6e, f) and pC (Fig. 6g, h) populations. The dark brown pA seeds (Fig. 6b) and both seed colors of pPA (Fig. 6c, d) showed better tolerance in the presence of 50 mM and 100 mM NaCl in the in vitro germination medium.

Discussion

This study, for the first time, provides scientific evidence and describes the presence of color heteromorphism in the seeds of four C. quitensis populations grown under controlled conditions, originating from habitats with varying marine influence: pA, a coastal Antarctic population; pPA, a sub-Antarctic coastal population that develops in soils flooded by seawater; pL, a sub-Antarctic coastal population; and pC, an Andean population not exposed to marine influence (Supplementary Fig. 1). This phenotypic characteristic in the seeds contributes to the salinity tolerance of the different C. quitensis populations.

The C. quitensis triangular and kidney-shaped seed morphology (Fig. 1) agrees with previous descriptions, where it is mentioned that seeds tend to be flattened and wider towards the cotyledon area32. Conversely, variations in seed testa microstructure, dormancy, and germination are associated with seed coloration33. In particular, the effect of seed color on germination varies among species8,9.

SEM analysis performed in lateral view reflected little variation in testa structure, with striations evident only in the dark pPA seeds (Fig. 1d). However, a close-up of the seed micropyle area revealed that heteromorphic seeds from all populations show striations that form small pieces of a puzzle (Fig. 1i-p). Similar shallow marks were previously detected on the surface of the periclinal walls of the pA testa32. It is possible that light and dark brown seeds differ in their biochemical and structural composition at the deeper layers of the seed coat, so more detailed analyses, including the use of Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, may be required34. Genes regulating the synthesis of flavonols and proanthocyanidin pigments, along with other chemicals, are known to play a crucial role in determining seed coat color and their arrangement is found in the different layers of the seed coat35,36. However, this study did not cover these aspects, so further research is necessary to understand the factors that lead to heteromorphism in C. quitensis. Seed coat characteristics play an ecological role in species dispersal, longevity, water uptake capacity, and germination in ecosystems dominated by changes in temperature, salinity, and water availability37.

The wide distribution of C. quitensis has generated genetic and morphological differentiation among its populations27,38, which influences their germination30. Plants growing in cold climates are usually small in size and slower growing than their counterparts. Therefore, they produce small seeds with dormancy, showing low germination speed and high temperature requirements for germination39. Antarctic populations of C. quitensis have been reported to have lower germination relative to sub-Antarctic or Andean populations27, respectively. However, in this study, the Antarctic population pA showed equal germination percentage and T50 to the sub-Antarctic population pL (Fig. 2a, b).

Seed heteromorphism is a critical adaptive mechanism that enables plants to maintain high germination rates under stress conditions like high salinity and intense UV radiation40, significantly influencing the ecological resilience of plants to changes in the environment41. C. quitensis frequently encounters these stressors within its natural habitats, making this mechanism particularly vital. Factors such as seed maturity, flavonoid and pigment concentrations, environmental variations, and genetic influences all play a role in testa pigmentation42. Consequently, under increasing salt concentrations, seed heteromorphism is expected to differentially affect the germination of C. quitensis populations (Figs. 4, 5 and 6). However, this character only contributed to the higher salinity tolerance of dark brown pA seeds, inferring, therefore, that seed color heteromorphism might be fundamental for this population to tolerate increased salinity conditions to a greater extent in Antarctic.

The testa thickness of heteromorphic seeds is determined by the amount of suberin, cutin, and lignin in the cell walls, as well as the presence of fatty acids in the intercellular spaces. This thickness influences seed permeability, impacting the rate of water uptake by the embryo, dormancy, and germination43,44. Additionally, the levels of phytohormones such as abscisic acid, indole-3-acetic acid, and zeatin riboside vary with seed color, potentially affecting the germination process45. Understanding these complex interactions provides valuable insights into the resilience mechanisms of C. quitensis, offering potential strategies for enhancing crop tolerance to abiotic stressors.

Varieties or genotypes among species exhibit different levels of tolerance to the same stress46, a phenomenon observable from the early stages of plant development47. For instance, dark brown pA seeds demonstrated a higher germination percentage than light brown seeds up to 150 mM NaCl (Fig. 4a). However, in the presence of 150 and 200 mM NaCl, light brown pPA seeds showed a higher germination percentage than dark brown seeds (Fig. 5b). This suggests that within a population, the higher germination percentage of one seed type over another indicates the possible presence of biochemical compounds that enable tolerance to NaCl. Both pA and pPA populations thrive in areas exposed to saline conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b)19,20, suggesting they possess genetically determined mechanisms that confer salinity tolerance. Previous research has shown that the addition of 50 mM NaCl to in vitro culture media did not affect the germination percentage of pPA compared to seeds germinated under non-saline (control) conditions21,22.

Nevertheless, in this investigation, pPA seeds with a dark brown color exhibited a greater germination percentage when the in vitro germination media did not contain NaCl (Figs. 3a and 4b). The pPA has a higher tolerance to salt than pL, even though both species originate in similar locations and are associated with coastal ecosystems (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). A possible reason could be that the pPA ecosystem undergoes frequent flooding of the soil with seawater, exposing the roots to continuous and direct contact with saltwater20. This may have led to the development of stronger genetic mechanisms in this population that can tolerate salinity. Because the habitats and microclimates that comprise a natural landscape are ever-changing. Therefore, the populations that grow there tend to show differences in response to environmental pressures48. However, pL is subject to strong anthropic pressure that has influenced its habitat and therefore the ecology of this population (M. Cuba-Díaz, pers. comm.). This could also explain why, although they grow in Punta Arenas associated with coastal environments, pL and pPA have different levels of salt tolerance.

Both pL and pC showed low tolerance to salinity (Fig. 4c, d). However, at concentrations up to 100 mM NaCl, pPA seeds and only the dark brown seeds of pA had a germination percentage higher than 50% (Fig. 4a, b). The observed difference in salinity tolerance between pPA and pA could be attributed to the different ways these populations are exposed to salinity: pPA is found in areas that are flooded with seawater, while pA receives marine spray. This distinction should be analyzed in depth. For this experiment, seeds were obtained from plants grown under controlled conditions and temperatures, without exposure to salinity for at least 8 to 10 months49. Nonetheless, seeds from pPA and the dark brown seeds from pA exhibited greater tolerance to salinity, suggesting the presence of genetically inherited mechanisms that confer tolerance, even in the absence of direct exposure to saline conditions during their production.

For each population, it is evident that when the concentration of NaCl increases, seeds of all colors are impacted. In fact, there was a delay in seed germination, starting with an increase in salt concentration (Fig. 4). In numerous species, studies have documented the negative influence of salinity46,50,51 because the increase of Na+ ions in the medium decreases the water uptake rate of seeds, generating drought stress, thereby delaying and decreasing germination percentage52. Furthermore, it generates toxicity that changes and disrupts the activity of enzymes involved in nutrient mobilization, such as α-amylase, and decreases the content of gibberellins required for germination50,53.

Researchers have observed that C. quitensis does not germinate quickly under laboratory conditions. The development of long germination periods is considered an adaptive trait in species that occur in ecosystems with a high degree of stress or disturbance54. However, in this study, pA and pPA required less time to achieve 50% germination (Fig. 5a, b) than pL and pC (Fig. 5c, d). This is advantageous because faster-germinating plants are less susceptible to disease and experience less competition for environmental resources, both of which are critical for healthy growth and subsequent seed production55.

This research shows that there is a close relationship between seed color and the germination of C. quitensis in response to salinity. Although this phenomenon was not observed in the other three populations, it is possible, according to the literature, that seed heteromorphism may be a useful mechanism for tolerating other types of environmental stress, in the remaining populations of C. quitensis. Considering that the thickness of the testa, the composition and abundance of chemical compounds in the seed coat, and the presence of secondary metabolites in seeds may provide relevant information about the ecology of species in extreme environments7. Finally, there is a need for further investigation focusing on seed heteromorphism to clarify the causes of its origin and its implications for the species’ ecology (Fig. 7).

While heteromorphism has been documented in the Caryophyllaceae family26, this is the first report of such a phenomenon in C. quitensis, highlighting an additional adaptive strategy this species uses to endure the harsh conditions of its native habitats. Heteromorphism in seeds has been reported across numerous plant families, including Amaranthaceae41, Poaceae56, Fabaceae57, and Asteraceae58, many of which contain crops of economic importance. The discovery of heteromorphism in C. quitensis opens the possibility of leveraging this trait to understand seed survival mechanisms under variable environmental conditions. This knowledge could be instrumental in selecting populations, varieties, or genotypes of commercially significant species that exhibit enhanced tolerance to abiotic stresses, such as increased soil salinity.

Conclusion

This work represents the first effort to identify the existence of color heteromorphism in C. quitensis seeds from different habitats. The studied populations vary in their germination capacity, with dark brown seeds showing greater success than light brown ones. The most salt-tolerant population is pPA, where the heteromorphic seeds respond equally to the presence of NaCl. This opens the possibility of using pPA as a biotechnological model to investigate the mechanisms of salinity tolerance in extremophilic species. In pA, dark brown seeds showed a higher germination percentage than light brown seeds in the presence of NaCl, showing that heteromorphism is one of the mechanisms used by this population to cope with saline conditions. Heteromorphism in pL and pC did not influence their ability to withstand salt in the medium, making them the most susceptible populations. Finally, seed heteromorphism related color of seed coat in C. quitensis may be one of the strategies used by this species to tolerate the harsh conditions within its natural habitat, although the advantages of this phenomenon for the species need further study.

Materials and methods

Plant material

For this study, seeds from four populations of C. quitensis plants were analyzed 8 to 10 months after their collection in the field. These plants were kept in a common garden belonging to the Antarctic plant collection of the Laboratorio de Biotecnología y Estudios Ambientales of Universidad de Concepción, Chile. Seeds were coded with the name of the location where the plants were collected: Arctowski (pA) (King George Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica; 62°09’S; 58°28’W), La Marisma (pPA) (Santa María Point, South of Punta Arenas, Chile; 53°22’S; 70°58’W), Laredo (pL) (Laredo sector, North of Punta Arenas, Chile; 52°58’S; 70°49’W) and Conguillío (pC) (Conguillío National Park, Araucanía Region, Chile; 38°36’S; 71°36’W) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The populations pA, pPA, and pL are coastal populations, so they are constantly exposed to marine spray. Notably, pPA inhabits areas that are continuously flooded with seawater, while pC is located in the mountain range and does not receive marine influence.

C. quitensis plants were grown in growth chambers at 13 ± 1 °C, with a 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod, a light intensity of 120 ± 20 µmol m2 s− 1 and 85–90% relative humidity. Seeds from each population were collected when the flower capsules were fully opened, and the seeds were matured (Fig. 8a). Mature seeds were considered as those able to tolerate desiccation59 and whose color varied from immature seeds. The capsules were dried at room temperature for 2–3 days. Subsequently, seeds were manually extracted, sorted by color into light and dark brown seeds (Fig. 8b, c), and stored in hermetically sealed Eppendorf tubes at 4 °C until use.

Electron microscopy analysis

The light and dark brown seed testa of the different populations was analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (model JSM-6380) to detect differences in their morphology. Seeds from different colors were fixed to a holding plate and sputtered with an Au layer using a Leica EM ACE600 high vacuum coater. SEM images were taken using an acceleration voltage of 30 kV modified from Kellman-Sopyla et al.32.

Seed selection and conditioning

Seeds were submerged for 24 h in distilled water, and seeds that floated were considered non-viable and those that did not were considered viable60. All viable seeds were scarified with 1% (v/v) H2SO4 during 30s30 and subsequently disinfected with 70% (v/v) ethanol for 30 s in vortex and 5% (v/v) NaClO for 7 min in vortex, followed by three times washes with sterile distilled water21.

Effect of population, seed color heteromorphism and salinity on seed germination

For the experiments, 10 cm diameter Petri dishes were used containing 20 mL of MS culture medium61, 3% sucrose, 0.7% agar were prepared. Seeds were placed on dishes for in vitro germination at 20 ± 2 °C, with a 16 h light/ 8 h dark photoperiod and a light intensity of 45 ± 2 µmol m-2 s-1.

To evaluate the effect of populations (n = 4) on germination without making distinctions in seed color, an experimental design was carried out with 10 replicates per treatment (n = 40). Seeds were randomly selected, maintaining the color proportions for each population of C. quitensis and 15 seeds per replicate were placed to germinate in the mentioned medium.

In addition, to evaluate the effect of seed color2 within the population, five replicates of 15 seeds of the same color were used for each replicate and placed to germinate on the same medium.

Finally, to explore the combined effect of seed color and salt concentration, five concentrations of NaCl (0, 50, 100, 150 and 200 mM) were added to the medium. Five replicates of 15 seeds per color and NaCl concentration, respectively, were used.

For the three tests, the number of germinated seeds on each plate was recorded every 48 h for 32 days. Germinated seeds were considered to be those whose radicle was at least twice the size of the seed28. Data was calculated for germination percentage (GP) according to the Eq. 1.

Where n is the number of germinated seeds at the end of the experiment and N is the total number of seeds. In addition, it was determined the time at which 50% germination is reached (T50) according to the Eq. 262.

Where n is the number of germinated seeds at the end of the experiment; ni and nj are the cumulative number of germinated seeds per adjacent count at tj and ti times, respectively, where \(\:ni<\frac{N}{2}<nj\).

Based on these count data, it was obtained cumulative germination rate as the fraction of the number of germinating seeds per Petri dish every two days.

Statistical analysis

To analyze the effect of populations and seed heteromorphism on germination percentage and T50 of each population, a one-way ANOVA was performed. Germination percentage and T50 were considered as dependent variables, and population and seed color were used as independent variables. To evaluate whether color heteromorphism affects germination response to salt stress, a factorial analysis was performed. Germination percentage and T50 were again the dependent variables, while seed color and different salinity treatments acted as independent variables. In both analyses, a post hoc Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) analysis was employed with a 95% confidence interval. These analyses were executed using the “aov” function within the R Studio program (R Core Team, 2023). Subsequently, the graphs were generated utilizing the “ggplot2” package63.

Data availability

The data of this research are available upon request via email to the corresponding author.

References

Uçarly, C. Intech Open, UK,. Effects of salinity on seed germination and early seedling stage in Abiotic stress in plants (ed Fahad, S., Saud, S., Chen, Y., Wu, C., Wang, D.) 211–232 (2021).

Shahid, M. A. et al. Insights into the physiological and biochemical impacts of salt stress on plant growth and development. Agron 10, 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10070938 (2020).

Hameed, A. et al. Effects of salinity stress on chloroplast structure and function. Cells 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10082023 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Effective root responses to salinity stress include maintained cell expansion and carbon allocation. New. Phytol. 238, 1942–1956 (2023).

Irik, H. A. & Bikmaz, G. Effect of different salinity on seed germination, growth parameters and biochemical contents of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) seeds cultivars. Sci. Rep. 14, 6929. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55325-w (2024).

Liang, W., Ma, X., Wan, P. & Liu, L. Plant salt-tolerance mechanism: a review. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 495, 286–291 (2018).

Liu, R. R., Wang, L., Tanveer, M. & Song, J. Seed heteromorphism: an important adaptation of halophytes for habitat heterogeneity. Front. Plant. Sci. 9, 1515. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01515 (2018b).

Mandizvo, T. & Odindo, A. O. Seed coat structural and imbibitional characteristics of dark and light-colored Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranean L.) landraces. Heliyon 5, e01249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01249 (2019).

Sethi, R., Kaur, N. & Singh, M. Morphological and physiological characterization of seed heteromorphism in Medicago denticulata Willd. Plant. Physiol. Rep. 25, 107–119 (2020).

Nisar, F., Gul, B., Ajmal Khan, M. & Hameed, A. Germination and recovery responses of heteromorphic seeds of two co-occurring Arthrocnemum species to salinity, temperature and light. S. Afr. J. Bot. 121, 143–151 (2019).

Toderich, K. et al. Seed heteromorphism and germination in Chenopodium quinoa Willd. Related to crop introduction in marginalized environments. Pak. J. Bot. 55, 1–17 (2023).

Gul, B., Ansari, R., Flowers, T. J. & Khan, M. A. Germination strategies of halophyte seeds under salinity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 92, 4–18 (2013).

Ma, Y. et al. Seed heteromorphism and effects of light and abiotic stress on germination of a typical annual halophyte Salsola Ferganica in cold desert. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 2257. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.02257 (2018).

Bertini, L. et al. What Antarctic plants can tell us about climate changes: temperature as a driver for metabolic reprogramming. Biomolecules 11, 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11081094 (2021).

Cuba-Díaz, M., Rivera-Mora, C., Navarrete, E. & Klagges, M. Advances of native and non-native Antarctic species to in vitro conservation: improvement of disinfection protocols. Sci. Rep. 10, 3845. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60533-1 (2020).

Moore, D. M. Studies in Colobanthus Quitensis (Kunth) Bartl. And Deschampsia antarctica Desv. II. Taxonomy, distribution and relationships. Br. Antarct. Surv. Bull. 23, 63–80 (1970).

Meinke, D. W., Cherry, J. M., Dean, C., Rounsley, S. D. & Koornneef, M. Arabidopsis thalaana: a model plant for genome analysis. Sci 282, 662–682 (1998).

Niedbała, G., Niazian, M. & Sabbatini, P. Modeling Agrobacterium mediated gene transformation of Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum)—a model plant for gene transformation studies. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 695110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.695110 (2021).

Convey, P. et al. The spatial structure of Antarctic biodiversity. Ecol. Monogr. 84, 203–244 (2014).

Cuba-Díaz, M., Acuña, D., Klagges, M., Dollenz, O. & Cordero, C. Colobanthus quitensis de la Marisma, una nueva población para la colección genética de la especie in Avances en Ciencia Antártica Latinoamericana. Libro de Resúmenes VII Congreso Latinoamericano de Ciencia Antártica, Chile, 436–439 (2013).

Cuba-Díaz, M., Castel, K., Acuña, D., Machuca, A. & Cid, I. Sodium chloride effect on Colobanthus quitensis seedling survival and in vitro propagation. Antarct. Sci. 29, 45–46 (2017a).

Castel, K. Evaluación de tolerancia a la salinidad (NaCl) de tres poblaciones de Colobanthus quitensis in vitro. Tesis de Pregrado de Ingeniería en Biotecnología Vegetal. Universidad de Concepción, Chile (2015).

Arroyo-Marín, F. B. Respuestas diferenciales en la tolerancia a la salinidad en poblaciones de Colobanthus quitensis Kunth (Bartl.). Tesis de Pregrado de Ingeniería en Biotecnología Vegetal. Universidad de Concepción, Chile (2023).

Kranner, I., Minibayeva, F. V., Beckett, R. P. & Seal, C. E. What is stress? Concepts, definitions and applications in seed science. New. Phytol. 188, 655–673 (2010).

Mbinda, W. & Kimtai, M. Evaluation of morphological and biochemical characteristics of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) varieties in response salinity stress. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol. 33, 1–9 (2019).

Ullah, F. et al. Seed micromorphology and its taxonomic evidence in subfamily Alsinoideae (Caryophyllaceae). Microsc. Res. Tech. 82, 250–259 (2018).

Cuba-Díaz, M. et al. Phenotypic variability and genetic differentiation in continental and island populations of Colobanthus Quitensis (Caryophyllaceae: Antarctic pearlwort). Polar Biol. 40, 2397–2409 (2017b).

Sanhueza, C. et al. Growing temperature affects seed germination of the Antarctic plant Colobanthus Quitensis (Kunth) Bartl (Caryophyllaceae). Polar Biol. 40, 449–455 (2017).

Koc, J. et al. The effects of methanesulfonic acid on seed germination and morphophysiological changes in the seedlings of two Colobanthus species. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 87, 3601. https://doi.org/10.5586/asbp.3601 (2018b).

Cuba-Díaz, M., Acuña, D. & Fuentes-Lillo, E. Antarctic pearlwort (Colobanthus Quitensis) populations respond differently to pre-germination treatments. Polar Biol. 42, 1209–1215 (2019).

Dulska, J. et al. The effect of sodium fluoride on seeds germination and morphophysiological changes in the seedlings of the Antarctic species Colobanthus Quitensis (Kunth) Bartl. And the subantarctic species Colobanthus Apetalus (Labill.) Druce. Pol. Polar Res. 40, 255–272 (2019).

Kellmann-Sopyla, W., Koc, J., Górecki, R. J., Domaciuk, M. & Gielwanowska, I. Development of generative structures of polar Caryophyllaceae plants: the Arctic Cerastium alpinum and Silene involucrata, and the Antarctic Colobanthus Quitensis. Pol. Polar Res. 38, 83–104 (2017).

Loades, E. et al. Distinct hormonal and morphological control of dormancy and germination in Chenopodium album dimorphic seeds. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1156794. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1156794 (2023).

Waskow, A., Howling, A. & Furno, I. Advantages and limitations of surface analysis techniques on plasma-treated Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Front. Mater. 8, 642099. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2021.642099 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Transcriptome analysis of a new peanut seed coat mutant for the physiological regulatory mechanism involved in seed coat cracking and pigmentation. Front. Plant. Sci. 7, 01491. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01491 (2016).

Cao, J. et al. Effects of genetic and environmental factors on variations of seed heteromorphism in Suaeda Aralocaspica. AoB Plants. 12, plaa044. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plaa044 (2020).

Baskin, C. C. & Baskin, J. M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination 2nd edn (Academic Press - Elsevier, 2014).

Koc, J. et al. Range-wide pattern of genetic variation in Colobanthus Quitensis. Polar Biol. 41, 2467–2479 (2018a).

Rosbakh, S., Chalmandrier, L., Phartyal, S. & Poschlod, P. Inferring community assembly processes from functional seed trait variation along elevation gradient. J. Ecol. 110, 2374–2387 (2022).

Xie, J. et al. Seed color represents salt resistance of alfalfa seeds (Medicago sativa L.): based on the analysis of germination characteristics, seedling growth and seed traits. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1104948. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1104948 (2023).

Žerdoner-Čalasan, A. & Kadereit, G. Evolutionary seed ecology of heteromorphic Amaranthaceae. Perspectives in plant ecology. Evol. Syst. 61, 125759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2023.125759 (2023).

Debeaujon, I., Lepiniec, L., Pourcel, L. & Routaboul, J. M. Seed development, dormancy and germination, in: (eds Bradford, K. J. & Nonogaki, H.) Seed coat Development and Dormancy. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, USA, 25–49 (2007).

Kelly, K. M., Staden, J. V. & Bell, W. E. Seed coat structure and dormancy. Plant. Growth Regul. 11, 201–209 (1992).

Marles, M. A. S. & Gruber, M. Y. Histochemical characterization of unextractable seed coat pigments and quantification of extractable lignin in the Brassicaceae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 84, 251–262 (2004).

Wang, F. X. et al. Salinity affects production and salt tolerance of dimorphic seeds of Suaeda salsa. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 95, 41–48 (2015).

Dehnavi, A. R., Zahedi, M., Ludwiczak, A., Cardenas, S. & Piernik, A. Effect of salinity on seed germination and seedling development of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) genotypes. Agronomy 10, 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10060859 (2020).

Pinheiro, C. et al. Salinity effect on germination, seedling growth and cotyledon membrane complexes of a Portuguese salt marsh wild beet ecotype. Theor. Exp. Plant. Physiol. 30, 113–127 (2018).

Lum, T. D. & Barton, K. E. Ontogenetic variation in salinity tolerance and ecophysiology of coastal dune plants. Ann. Bot. 125, 301–314 (2020).

Xiong, F. S., Mueller, E. C. & Day, T. A. Photosynthetic and respiratory acclimation and growth response of Antarctic vascular plants to contrasting temperature regimes. Am. J. Bot. 87, 700–710 (2000).

Liu, L. et al. Salinity inhibits rice seed germination by reducing α-amylase activity via decreased bioactive gibberellin content. Front. Plant. Sci. 9, 275. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00275 (2018a).

Javaid, M. M. et al. Influence of environmental factors on seed germination and seedling characteristics of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L). Sci. Rep. 12, 9522. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13416-6 (2022).

Misra, N. & Gupta, A. K. Effect of salt stress metabolism in two high yielding genotypes of green gram. Plant. Sci. 169, 331–339 (2005).

Ryu, H. & Cho, Y. G. Plant hormones in salt stress tolerance. J. Plant Biol. 58, 147–155 (2015).

Brits, G. J., Brown, N. A. C., Calitz, F. J. & Van Staden, J. Effects of storage under low temperature, room temperature and in the soil on viability and vigor of Leucospermum cordifolium (Proteaceae) seeds. S. Afr. J. Bot. 97, 1–8 (2015).

Bueno, M. Adaptation of halophytes to different habits. In: Jiménez-López JC ed. Seed dormancy and germination. IntechOpen 97–120 (2020).

Wang, A. B., Baskin, C. C., Baskin, J. M. & Ding, J. Environmental and seed-position effects on viability and germination of buried seeds of an invasive diaspore-heteromorphic annual grass. Physiol. Plant. 176, e14353. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.14353 (2024).

Wango, M., Medaglia-Mata, A., Villalta-Romero, F., Alvarado-Marchena, L. & Rocha, O. J. Relationship between flooding regimes, time of year, and seed coat characteristics and coloration within fruits of the annual monocarpic plant Sesbania emerus (Fabaceae). Int. J. Plant. Sci. 182, 295–308 (2021).

Junting, L. et al. Seed and fruiting phenology plasticity and offspring seed germination rate in two Asteraceae herbs growing in karst soils with varying thickness and water availability. J. Resour. Ecol. 13, 319–327 (2022).

Still, D. W. Development of seed quality in Brassicas. HortTechnology 9, 335–340 (1999).

Suma, N. & Srimathi, P. Influence of water flotation technique on seed and seedling quality characteristics of Sesamum indicum. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 7, 51–53 (2014).

Murashige, T. & Skoog, F. A revised medium for the rapid growth and bioassay with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473–497 (1962).

Farooq, M., Basra, S. M. A. & Hafeez, K. Thermal hardening: a new seed vigor enhancement tool in rice. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 47, 187–193 (2005).

Wilkinson, L. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis by Wickham. H Biometrics. 67, 678–679 (2011).

Funding

This work was supported by VRID 220.418.012 Project (Vicerrectoría de Investigación de Desarrollo, Universidad de Concepción); ANID/Scholarship Program/Doctorado Beca Nacional/2021-21210100 [YO]; INACH DT_05_22 Project (Instituto Antártico Chileno) [YO]; Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias de la Agronomía 2021300031, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de Concepción, Campus Chillán [YO]; Fondecyt 1231616 and ANID/BASAL FB210006 [EFL].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC-D, YO, GC-B, and DV-V: research design and acquisition of data; YO, FBA-M, and E-FL: data analysis; YO, EF-L, DN-C, and MC-D: interpretation of data, manuscript drafting and editing; GC-B, and MC-D: languages editing and revision. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ontivero, Y., Fuentes-Lillo, E., Navarrete-Campos, D. et al. Preliminary assessment of seed heteromorphism as an adaptive strategy of Colobanthus quitensis under saline conditions. Sci Rep 14, 31120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82381-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82381-z

This article is cited by

-

Accelerated aging in Colobanthus quitensis seeds: understanding stress responses in an extremophile species

Planta (2025)

-

Improved in vitro germination of Colobanthus quitensis: a key step for Antarctic plant conservation

Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) (2025)