Abstract

Vegetation restoration can be effective in containing gully head advance. However, the effect of vegetation restoration type on soil aggregate stability and erosion resistance at the head of the gully is unclear. In this study, five types of vegetation restoration—Pinus tabulaeformis (PT), Prunus sibirica (PS), Caragana korshinskii (CKS), Hippophae rhamnoides (HR), and natural grassland (NG, the dominant species is Leymus chinensis)—in the gully head were studied. Soil aggregate composition and nutrient contents in the 0–20, 20–40, and 40–60 cm soil layers were also determined, and the soil stability parameters were used to evaluate the soil conditions. The soil erodibility (K) was then determined by measuring the granulometric composition and organic matter. The results showed that the particle size of soil aggregates under different vegetation restoration types was mainly < 0.25 mm, and the percentage of aggregate disruption (PAD) was 22.08–76.07%. This further indicated that in Loess hilly and gully regions, water-stable aggregates were more reflective of the stability of soil aggregates in a gully head under vegetation restoration. The > 0.25 mm aggregates (R> 0.25 mm), geometric mean diameter (GMD), and mean weight diameter (MWD) values of the three soil layers were the highest in PT and the lowest in NG, while the opposite was true for fractal dimension (D) and the percentage of aggregate disruption (PAD). The K ranged from 0.052 to 0.065 t·hm2·h·MJ− 1 mm− 1·hm− 2. GMD can be used to characterize the anti-erosion ability of soil, and increasing the soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, and clay content can effectively reduce soil erodibility. The comprehensive analysis indicated that the soil aggregates of arbors planted in the gully head had the highest stability and anti-erodibility, followed by shrubs and grasslands, and can be used to evaluate vegetation restoration measures in gully heads.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scholars and organizations from numerous countries are concerned about soil erosion, which is a global issue1. The Loess Plateau suffered some of the worst soil erosion in the world, which threatens the plateau’s ecosystem and food security by causing massive soil and water loss2,3. Gully erosion is the most common form of soil erosion and the main cause of soil and water loss in small watersheds4,5. At present, the areas experiencing soil erosion in the gullies of small watersheds represent over 50% of the whole land area experiencing erosion6. Gully head retrospective erosion plays an important role in gully erosion7. Under rainfall conditions, the gully head is continuously scoured by runoff and becomes unstable, which can lead to significant migration of the gully head and the aggravation of soil erosion. The environment has been restored since 1999, when China implemented the policy of converting farming back to forest and grassland, and gully erosion has been curbed to a certain extent. In particular, the vicinity of the gully head in the Loess Plateau has been transformed into grasslands or artificial forests, and the migration of the gully head has been effectively controlled8. By decreasing soil erodibility and increasing soil stability, vegetation can greatly slow down the gully head’s advancement9,10. Therefore, research into the impacts of different vegetation restoration methods on the soil characteristics and erodibility of gully heads in Loess hills and gully regions can serve as a foundation for scientifically selecting gully head protection vegetation strategies.

Soil aggregates are the fundamental units of soil structure11. High-quality aggregates and appropriate particle size distribution can form a good soil structure, multi-stage porosity between agglomerates, and water storage and air permeability at the same time, but also be conducive to microbial activities and the accumulation of organic matter and available nutrients. And the agglomerate structure is mostly organic and inorganic colloid formation; humus and nutrient content are high; and cation exchange capacity is large, so the fertilizer retention performance is strong. The risk of soil erosion can be decreased, and soil productivity and erosion resistance can be increased with good soil aggregates12. Many researchers have found that the soils of different tree species exhibit large differences in their properties owing to the different effects of root systems, litter properties, and understory vegetation conditions, and the resulting characteristics of the associated soil aggregates reflect these comprehensive effects13,14,15. In terms of the root system, soil in woodlands often has an increased fine root biomass and enhanced tensile properties, both of which support the stability of the soil layer and allow it to synergize with organic matter to form sticky secretions. This increases the cohesion between soil particles, thus promoting the formation of macroaggregates16. The amount of litter under different vegetation forests is different, leading to significant differences in the soil roughness and infiltration rate. The optimal amount of litter accumulation can effectively intercept surface runoff, improve the soil pore structure, and increase soil stability17. In the artificial forests of China’s Loess Plateau, understory vegetation restoration has the capacity to boost total carbon sequestration and promote large aggregate formation, which enhances aggregate stability18.

The process of soil erosion from raindrop splashing to gully erosion can be divided into interrill erosion, rill erosion, and gully erosion according to different dominant forces. These three types of erosion have different erosion mechanisms, morphological characteristics, and effects on soil59,. Gully head retrospective belongs to gully erosion, and scholars have adopted different indicators to reflect soil erodibility characteristics under the influence of different leading forces. In USLE, RUSLE, and EPIC models, the soil erodibility K factor is widely used to reflect soil erosion sensitivity characteristics, and The calculation of K mainly depends on the soil property index, covering the erosion processes such as rill erosion, interrill erosion, and gully erosion. The application of K is of great significance for the prediction of scale erosion. The EPIC model is widely used and has high adaptability in loess hilly areas38.

Restoring vegetation can enhance ground cover, boost nutrient fixation in the soil, avoid soil degradation, and effectively prevent soil erosion19. There are significant differences in soil nutrients between the various types of vegetation restoration. Dong et al.20 examined the soil properties of arbor land, shrub land, and grassland in a small watershed in the Loess Plateau. The findings demonstrated that vegetation restoration may effectively increase soil nutrients and improve soil anti-erodibility, and that shrub land had the greatest impact on soil fertility. Researching differences in soil stoichiometric properties under two vegetation restoration models (woodland and grassland) in the Loess Plateau, Liu and Wang21 discovered that soil depth and vegetation restoration types had a substantial impact on soil nutrients and stoichiometric properties, with woodland having a greater improvement effect on soil nutrients. Therefore, the restoration effect of different vegetation types can be clarified by the changes in soil nutrients.

Soil aggregate is one of the important factors affecting soil erosion and surface runoff22; The sensitivity of soil to erosion and the movement of external erosion forces were reflected in soil erodibility, which is an inner factor influencing the incidence and progression of soil and water loss23; The buffer and stability of the soil environment can be directly or indirectly impacted by the physical and chemical characteristics of the soil24. All three are intrinsic properties of soil, and there is a correlation between them25. The gully heads’ soil and root systems under different vegetation types and regions were found to differ significantly26, which also means that the soil erodibility shows strong heterogeneity and that the degree of retrospective erosion and morphological development varies; thus, the key influencing factors need to be further clarified. However, research on the characteristics of soil and resistance to erosion in areas with hills and gullies that have been restored to vegetation is mostly focused on the slope at present27. In the entire loess gully region, the gully head is the most active part of development and is closely associated with soil erosion28. This area’s soil is loose, and the erosion intensity is high. The soil consolidation, water conservation, soil improvement, and ecological benefits produced by vegetation restoration are more obvious, and the economic cost of gully head treatment is high. Determining the type of vegetation restoration that enhances gully head erosion resistance the best is therefore quite important. In this study, the understory soil’s stability and erodibility were examined after we chose five different vegetation restoration methods to study, with the aim of (1) examining how different types of vegetation restoration methods affect the distribution and stability of soil aggregates; (2) exploring how different vegetation restoration methods affect changes in soil nutrients; and (3) interpreting the rules governing variations in soil erodibility and its response mechanism to soil properties and determining the best soil and water conservation vegetation configuration at the gully head of the small watershed. The results of the research can be used as a reference for investigating gully head erosion mechanisms and vegetation configuration optimization in hilly and gully areas of loess.

Materials and methods

Study area

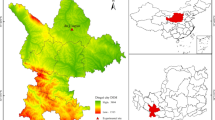

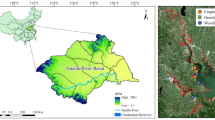

The study area is located in the Getuodian small watershed of Jungar Banner (111°08′–111°11′E, 39°54′–39°57′N), which belongs to the upper reaches of the Tahala River, a first-grade tributary of the Yellow River Basin, with a watershed area of 7 km2. This region experiences little rainfall and an average annual temperature of 7.3 °C, which is typical of a continental monsoon climate. The highest rainfall occurs in July, August, and September. There is about 386.4 mm of rainfall on average per year, while 758.0 mm of maximum precipitation has been measured (2022). The average annual evaporation is 2234.4 mm, which is greater than the rainfall, the drying index (d) exceeds 5, the average annual wind speed is 2.2 m·s− 1, and the frost-free period is 153 d. The soil type is mainly chestnut calcium soil (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO), the soil texture is silty loam (United States Department of Agriculture, USDA). The soil has a poor cementing capacity, and when it meets water, it is readily disrupted, exhibiting weak resistance to erosion. Gullies are easily formed after soil is washed away by heavy rainfall, and it is difficult to recover these gullies to their original state in a short period of time. The slope collects a large amount of runoff that scours the gully head, and the soil at the gully head is constantly eroded by water flow, resulting in serious forward movement. The rapid development of gully erosion has led to severe soil and water erosion, which has become the key factor inhibiting the sustainable development of agriculture in this region. At present, the vegetation in the basin primarily includes Pinus tabulaeformis, Prunus sibirica, Caragana korshinskii, Hippophae rhamnoides, and other artificial arbors and shrubs, Artemisia desertorum Schang, Elymus dahuricus, Leymus chinensis, and other natural grassland vegetation.

Experimental design and sampling site selection

First, the branch gully head’s vegetatiocn was thoroughly investigated. The survey results showed that over 90% of the branch gully head had been subjected to artificial treatment; the untreated area was natural grassland. According to data provided by the Water Conservancy Center, the vegetation restoration period was determined to be 15–20 years, and the average slope angle was 16°. Five types of gully head vegetation restoration with concentrated planting densities and mature forest ages—namely, PT, PS, CKS, HR, and NG—were selected as the research objects in the experiment, and the understory soil was collected for measurement to investigate the impact of different types of vegetation restoration on soil characteristics. To ensure that the sampling sites were representative, the sample plots included three PT and HR plots and four PS, CKS, and NG plots (Fig. 1). The slope and elevation were similar in the selected sample plots, the granule distribution changed little between plots, and the undergrowth vegetation grew evenly and made up a pure forest. Due to the differences in soil profiles caused by natural (rainfall, slope, parent material) and human-controlled (vegetation restoration) factors in the area, measurements were made in the 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, and 40–60 cm soil layers, respectively.

Diagram of the study area and sampling points of different vegetation types at the head of the gully locations. PS Pinus tabulaeformis, PS Prunus sibirica, CKS Caragana korshinskii, HR Hippophae rhamnoides, NG natural grassland. The mapping sofware is ArcGIS 10.8. URL: https://img01-xusong.91q.com/0 75A7F1D-C16B-4FFC-89C1 -03 9D11 A4B5 52.tif.

Soil sampling and treatment

The soil features of the gully head can be properly represented by soil within 5 m of it, as per the research conducted by Kompani-Zare et al.29. Three 1 × 1 m sampling points (repetitions) were set 2.5 m from the head of the gully in each plot. Because PT and PS are deep-rooted tree species, their roots are distributed in the subsurface 50–100 cm, but the fine roots and fine root biomass, which play a prominent role in improving soil erosion resistance, mainly exist in the 0–60 cm soil layer. When the soil depth exceeds 60 cm, the fine root biomass decreases to a relatively low level30,31,32. Therefore,, the excavation profile depth of each sample point was 60 cm, and undisturbed soil samples weighing 1 kg were collected in hard plastic boxes and sorted according to their depth into soil layers of 0–20, 20–40, and 40–60 cm. In total, 162 undisturbed soil samples were collected (one per layer × three layers/sample point × three sample points/plot×18 plots). Extrusion and inversion were avoided during the collection and transportation of undisturbed soil samples to avoid the destruction of aggregates. Gravel and plant roots were removed, and the soil was allowed to air dry at ambient temperature. After air drying, each large soil clod was broken along the natural cracks and then divided into three parts. A 10- mm sieve was used to determine the soil aggregates, and a 0.15- mm sieve was used to analyze the nutrients in the other part. A 2- mm sieve was used to filter the third part in order to determine the granulometric content of the soil33.

Soil sample analysis

For the mechanical-stable aggregate treatment, 100 g of soil samples were collected on the basis of the principles of the quartering procedure and placed in an electric vibrating sieve machine with apertures of 2, 0.25, and 0.053 mm from top to bottom. The samples were vibrated and sieved at a fixed frequency of 300 times min− 1 for 5 min to obtain four types of aggregates with particle sizes of 10 − 2, 2–0.25, 0.25 − 0.053, and < 0.053 mm, and their percentages were calculated.

For the water-stable aggregate treatment34, 50 g of air-dried soil samples were soaked in distilled water for 10 minutes and then placed in three sieves with different aperture sizes of 2, 0.25, and 0.053 mm from top to bottom. The XY-100 soil aggregate analyzer was used to conduct vertical shaking within a pure water setting (amplitude of 5 cm, frequency of 25 times·min− 1) for wet sieving to obtain four types of aggregates with sizes of > 2, 2–0.25, 0.25 − 0.053, and < 0.053 mm. The obtained aggregates with different particle sizes were dried at 50 °C and weighed.

Referring to the method of Dou et al.35, the K2Cr2O7 wet oxidation method was used to assess the soil organic carbon (SOC) content, the micro-Kjeldahl method was used to estimate the total nitrogen (TN) content, the molybdenum blue colorimetric method was used to determine the total phosphorus (TP) content.

A MasterSizer 2000 laser-measuring instrument device was used to determine the granulometric composition of the soil.

Statistical analysis

The formulas used to calculate the > 0.25 mm aggregate mass (R> 0.25 mm), the mean weight diameter (MWD), the geometric mean diameter (GMD), the percentage of aggregate disruption (PAD), the fractal dimension (D)36,37, and the soil erodibility factor (K)38 are as follows:

where MT is the total aggregate mass (g); M> 0.25 is the > 0.25 mm aggregate mass (g); \(\bar{\chi }_{i}\) is the average diameter of each particle size of the aggregate (mm); ωi is the percentage content of each particle size of the aggregate (%); and r is a yardstick for measuring the diameter of aggregates; Md, and Mw are the mass percentage of aggregates in > 0.25 mm dry sieve and wet sieve, respectively.

where SAN is the sand (0.05–2.0 mm) content (%), SIL is silt (0.002–0.05 mm) content (%), CLA is clay (< 0.002 mm) content (%), C is the SOC content (%), and SN1 = 1–SAN/100. K is the soil erodibility factor, and the unit is the American system. After calculation, the K value was multiplied by 0.1317 and converted into an international system unit, where t·hm2·h·MJ− 1·mm− 1·hm− 2.

Three sets of replicates were set up for each variable (including vegetation restoration types, soil depth, and aggregate particles) in this experiment. Excel 2016 software was used for calculating the mean value and standard deviation, and the results were represented as the mean value ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), trend tests, and Pearson correlation analysis were performed on different data groups using SAS9.4 software; OriginPro2021 software was employed to draw the analysis diagram. There was a strong correlation between soil properties in this study. Therefore, to ensure the rationality of the regression equation results, ridge regression analysis was performed using IBMSPSS Statistics 27 software, and variables with strong collinearity were removed to obtain stable ridge regression results that were consistent with reality to fit the relationship between the erodibility factor and the soil properties. The comprehensive score of soil anti-erodibility was obtained using factor analysis.

Results

Distribution of soil aggregates and the characteristics of the PAD under different types of vegetation restoration

Distribution of mechanical-stable aggregates

The composition of the mechanically stable aggregates obtained using the dry sieving method is shown in Fig. 2a. Soil depth, vegetation restoration type, and their interactions all had a major impact on how soil aggregates were distributed. The aggregate content changed in the different layers of soil under the five vegetation restoration types, initially decreasing, then increasing, and then decreasing, as the particle size decreased. The largest amount was accounted for by the 0.25 –0.053 mm aggregate, at 45.97–70.92%. The PT samples had the highest content of > 2 mm aggregates in the 0–20 cm soil layer, followed by NG, HR, PS, and CKS; in the 20–40 and 40–60 cm layers, the difference in the content of > 2 mm aggregates between HR and PS and that of CKS gradually decreased, but overall, PT and NG had the largest content, while CKS had the lowest. Between each soil layer, the content of the 2–0.25 mm aggregates was the highest in PT, followed by NG, and there was no significant difference between HR, PS, and CKS. R> 0.25 mm is an important indicator for assessing the stability of the soil aggregate structure quantitatively39. The aggregate structure is more stable, and the soil resistance to erosion is stronger when the value is higher. As shown in Fig. 3a, under dry sieve conditions, the formation and retention ability of mechanically stable macroaggregates was the best in PT (30.94–49.21%) and NG (28.85–43.28%), and the surface (0–20 cm) layer was in a better state than the middle (20–40 cm) and bottom (40–60 cm) layers.

(a) Composition of mechanical-stable aggregates. (b) Composition of water-stable aggregates, where the error is represented by three sets of repeated standard errors. Different capital letters denote a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the content of aggregates with different particle sizes for same vegetational type in the same soil layer, while different lowercase letters denote a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the content of the same particle size for different vegetational types in the same soil layer.

Distribution of water-stable aggregates

The composition of water-stable aggregates is shown in Fig. 2b. Aggregates were mainly concentrated in the < 0.053 mm particle size category, with a variation range of 36.51–76.01%, indicating that the macroaggregates under different types of vegetation restoration were disrupted into < 0.053 mm aggregates after encountering water. In the 0–20 cm soil layer, except for NG, under the other four vegetation restoration methods, the aggregate content changed in decreasing and then increasing trends as the particle size decreased, topping at a particle size of < 0.053 mm, while NG showed a gradual increase in the content of four particle sizes, indicating that a large number of > 2 mm aggregates in the grassland soil were crushed. In the 20–40 cm soil layer, HR and CKS also showed the same trend as NG; with the deepening of the soil layer, the ability of macroaggregates to resist impacts was weakened. In the 40–60 cm soil layer, the change trend of the aggregate content under the five types of vegetation was consistent. Combined with the analysis in Fig. 3b, it was found that under the condition of a water sieve, the formation and retention ability of water-stable macroaggregates was still the best under a PT (16.03–38.34%) forest. The surface (0–20 cm) layer was in a better state than the middle (20–40 cm) and bottom (40–60 cm) layers. However, the macroaggregates in NG soil were easily disrupted after water impact, and numerous macroaggregates were concentrated in the minimum particle size range.

Characteristics of the percentage of aggregate disruption (PAD)

The PAD under different treatments ranged from 22.08 to 76.07% and increased significantly with the deepening of the soil layer (Fig. 3c). In the 0–20 cm soil layer, the disruption rates of PT (22.08%) and PS (23.66%) were low, and the difference between the two was not significant. The surface soil under the arbor forest stands (PT and PS) reflects the superiority of this type of vegetation restoration. The PAD values of the 20–40 and 40–60 cm soil layers were ranked as NG (72.63%, 76.07%) > HR (58.80%, 72.26%) > CKS (51.08%, 66.70%) > PS (35.26%, 50.68%) > PT (24.85%, 47.88%).

(a) Composition of soil mechanical-stable macroaggregates (R> 0.25 mm). (b) Composition of soil water-stable macroaggregates (R> 0.25 mm). (c) Percentage of aggregate disruption. Different capital letters denote a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the content of aggregates with different vegetational types in the same soil layer, while different lowercase letters denote a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the content of aggregates with same vegetational type in different soil layers.

Stability characteristics of soil aggregates in the gully head under different types of vegetation restoration

Analyzing the soil water-stable characteristics of different types of vegetation restoration revealed that for the MWD and GMD values of different soil layers, the other three vegetation restoration models, except NG and HR, were greatly affected by the soil layer (Table 1). The GMD values of NG and HR were the highest in the 0–20 cm soil layer, and the difference between the 20–40 cm soil layer and the 40–60 cm soil layer was not significant. The dimensions and distribution in soil granulometry were reflected in the GMD value, which demonstrated that there were similarities in the soil granulometry between NG and HR in the 20–60 cm soil layer. The diameter index between different soil layers was in the order of PT > PS > CKS > HR > NG. The D value was calculated using regression analysis, revealing that the change between the soil layer and vegetation was opposite to the diameter index, and the difference was significant. Overall, in each soil layer, the stability of PT (0.10–0.24 mm, 0.58–1.58 mm) and PS (0.08–0.20 mm, 0.43–1.39 mm) aggregates was highest, and the stability of NG (0.05–0.10 mm, 0.18–0.72 mm) was lowest.

Characteristics of soil nutrient in the gully head under different types of vegetation restoration

The content of nutrients in the soil differed significantly depending on the type of vegetation restoration (Table 2). The SOC content of PT, PS, and CKS decreased with each soil layer, while the SOC content of the HR was the highest in the 0–20 cm soil layer, followed by the 40–60 cm soil layer, and was the lowest in the 20–40 cm soil layer. The SOC content of the NG surface layer was significantly higher than that of the 20–60 cm soil layer, and there was no significant difference between the 20–40 and 40–60 cm soil layers. The overall trends across soil layers were that the SOC content of PT (1.10–1.35 g·kg− 1) and PS (0.85–0.99 g·kg− 1) was higher, that of NG (0.44–0.57 g·kg− 1) was the lowest, the carbon sequestration effect of the arbor was best, and the change in TN was large, the same as that of SOC. The change in TP was different from that in SOC and TN. The TP content under HR was significantly affected by the soil layer, and it was higher than the other vegetation types. As the soil layer became deeper, the content got lower. PT and NG’s 0–20 cm soil layers had a significantly higher TP content than the 20–60 cm soil layer. The TP content under PS and CKS had no obvious relationship with the soil layer, and the phosphorus content of each vegetation type changed significantly at 20–40 cm. The phosphorus content of CKS, which is also a shrub, was 28% lower than that of HR, demonstrating that the two capacities to absorb and use phosphorus from the soil differed significantly.

Changes in soil granulometric composition and erodibility factor K

The content characteristics of clay, silt, and sand in the soil profile are shown in Fig. 4a. The soil under different vegetation restoration treatments was dominated by silt and sand, and the silt content reached more than 50%. The clay content of the 0–20 cm soil layer was significantly greater than that of the 20–60 cm soil layer. The clay content of HR and NG was similar in each soil layer and was smaller than that of the first three. The change in silt and sand content between the soil layers was opposite to that of clay content, indicating that with the deepening of the soil layer, the soil viscosity decreased and gradually exhibited desertification. According to the calculation of the soil granulometric composition and organic carbon (Fig. 4a, Table 2), the soil erodibility factor K of different vegetation restoration gully heads was between 0.052 and 0.065 t·hm2·h·MJ− 1·mm− 1·hm− 2 (Fig. 4b), and the soil anti-erodibility was poor. In the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm soil levels, there was not a significant difference in K between PS and NG, however, it was significantly lower in the 40–60 cm soil layer. The other types of vegetation restoration demonstrated significant layer-by-layer increases. Between the same soil layers, NG (0.064–0.065) > HR (0.062–0.064) > CKS (0.060–0.061) > PS (0.057–0.060) > PT (0.052–0.057), and the difference was significant.

(a) Composition of soil granulometric. Different capital letters denote a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the content of granulometrics for different vegetation types in the same soil layer, while different lowercase letters denote a significant difference (p < 0.05) in the content of granulometrics for same vegetational type in the different soil layers. (b) Soil erodibility factor (K). Different capital letters denote a significant difference (p < 0.05) in different soil layers under the same vegetational type, and different lowercase letters denote a significant difference (p < 0.05) between different vegetational types in the same soil layer.

Relationship between K and soil aggregate characteristics and comprehensive evaluation

Through ridge regression analysis of K, aggregate composition, the stability index, soil nutrients, and granulometric composition (Table 3), it was found that the explanatory variables that had the greatest impact on K were GMD, SOC, TN, and clay content, and the four indicators were significantly negatively correlated with K (P < 0.01). The relationship between the aggregate stability index and soil properties was further analyzed (Table 4), and the results showed that the R> 0.25 mm, MWD, and GMD values showed a highly significant positive correlation with the > 0.25 mm particle size aggregate content, SOC, TN, and clay content, and a highly significant negative correlation with the < 0.053 mm particle size aggregate content (P < 0.01). The opposite was true for D and PAD, where they were positively correlated with powder silt content but not significantly so.

The comprehensive score of the soil erosion resistance is shown in Fig. 5. The scores were as follows: PT (1.73) > PS (− 0.21) > CKS (− 1.10) > HR (− 1.33) > NG (− 1.39). The findings demonstrated that soil aggregates’ stability and resistance to erosion were highest under PS conditions and lowest under NG conditions. Overall, it can be seen that arbors are better as gully head control measures in a small watershed, followed by shrubs, and grassland stability is poor.

Discussion

Effects of vegetation restoration on the distribution of soil aggregates in gully head

In the head of the branch gully in the small watershed of a loess hilly and gully region, soil aggregates under different vegetation restoration conditions were analyzed using dry and wet sieve methods in this study. The findings demonstrated that microaggregates with < 0.25 mm dominated both water- and mechanically stable aggregates. The main reason for this was that the soil texture of the gully head was chestnut soil, with a loose texture, low organic matter content, and lack of cohesion, which made it easier for microaggregates to form40. Furthermore, the area had a high altitude, a dry climate, fewer and less concentrated rains, and the soil was in a dry state for a long time. Because of this, it was easily impacted by the external pressures of water erosion. In the process of raindrop impact and water erosion caused by rainfall, soil microaggregates with different particle size ranges exhibit different fragmentation mechanisms and migration sorting rules. The cementing material in the microaggregates determines the degree of fragmentation of the aggregates. Calcium carbonate mainly exists in the particle size of 0.25 –0.053 mm, and free iron oxide mainly exists in the particle size of < 0.053 mm41. Soil clumps under the surface aggregation of calcium carbonate and is easily dispersed after water impact, and free oxidation is beneficial to the formation and stability of minimum aggregates. Meanwhile, runoff is particle selective, transporting particles and aggregates much finer than the soil matrix, leading to the development of microaggregates42,43,44. The > 0.25 mm mechanically stable aggregates in each soil layer of different vegetation restorations were the strongest in PT and NG. However, after the wet sieve treatment, the order from large to small was PS, PS, CKS, HR, and NG, and this order was significantly affected by the soil layer. This shows that the mechanical aggregates of NG are more stable in the natural state without damage, but they are easily broken into smaller aggregates after the extrusion of an external force (water). It can be seen from the disruption rate that the water-stable aggregates are more representative of the stability of soil aggregates in the gully head of the Loess hilly and gully regions. This is different from the findings of earlier research45, primarily because the soil is more scoured and eroded by runoff in the gully head erosion area. Planting PT and PS can fix soil particles through the winding effect of their deep roots, strengthen the soil matrix, and increase the shear resistance of the soil46,47, thus slowing down the expansion of the gully head. The roots of natural grassland are relatively shallow, relatively vulnerable to wind erosion, grazing, and other reasons, and the rainfall at the gully head is unevenly distributed, resulting in low soil water content, which is sensitive to water changes and does not have the same water-holding effect as woodland canopy throttling and litter accumulation and water holding48, When the water conditions change, the formation of water-stable macroaggregates is limited. The fundamental cause for the difference in the soil profile is that the soil is prone to compaction under long-term natural and man-made control. As the soil layer deepens, the pressure gradually increases, causing the decrease in soil porosity and difficulty in forming and stabilizing large aggregates. Simultaneously, owing to the effect of surface biomass, it helps make macroaggregates form and remain stable49.

Effects of vegetation restoration on the stability of soil aggregates in gully head

The stability index of soil aggregates represents the anti-erosion ability of the soil50. The advancement of gully heads can be slowed down through enhancing soil aggregate stability. According to many studies, the greater the R> 0.25 mm, MWD, and GMD values, the smaller the PAD and D values, and the better the aggregate stability51. The stability of soil aggregates in arbor and shrub forests was found to be higher in this study than in natural grassland, suggesting that afforestation at the gully head might substantially increase soil structure stability. Among them, tree vegetation had the most significant effect on the stability of the soil physical structure, followed by shrub vegetation. This may be because the community structure of arbor vegetation is better than that of shrubs, and the improved function of understory soil is stronger, which facilitates the promotion of nutrient accumulation and absorption52. Guo et al.9 also found that the diameter index of aggregates in the gully head of woodlands was higher, and the vegetation’s root system was mostly responsible for the difference. The poor stability of soil under HR shrub forests may be due to the high prevalence of local pests and diseases and the lack of appropriate management measures. After death, the root fixation ability is weakened, and the soil is prone to erosion and collapse, which makes it difficult for soil aggregates to form and stay stable. Vegetation diversity can improve soil stability through a variety of mechanisms, according to Chen et al.53. In this study, the herbaceous plants in the gully head are mainly Artemisia desertorum Schang, Elymus dahuricus, and Leymus chinensis, and the diversity is low; as a result, the effect of stabilizing the gully head is poor.

Effects of vegetation restoration on soil erodibility in gully head

The ease and difficulty of soil erosion are characterized by soil erodibility, which also indicates how sensitive the soil is to the separation and movement of erosion by outside factors54. Soil with a higher K value is more susceptible to erosion. In this study, it was found (Fig. 4a,b) that under different vegetation recovery, the highest K value could reach 0.065 t·hm2·h·MJ− 1·mm− 1·hm− 2, indicating that soil erosion resistance was poor at the position of gully head. In the 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, and 40–60 cm soil layers, the K value of NG was the highest, and the K value of shrubs and trees was lower than that of NG plots, and the K value increased with the deepening of the soil layer. Therefore, vegetation restoration is conducive to improving the erosion resistance of the soil at the head of the gully, and the surface soil is more stable, which is similar to the research results of An et al.63 and Wang et al.55. On the basis of the same soil texture, minerals, and other conditions, vegetation restoration can affect the stability of aggregates through root systems, litter properties, and understory vegetation and cause changes in soil erosion resistance again56. With vegetation restoration, soil clay, organic carbon, and total nitrogen contents increase, thereby improving soil aggregate stability and reducing soil sensitivity to erosion57.

Main factors driving soil aggregate stability and soil erodibility

Many factors influence the soil erodibility. This study showed that GMD, SOC, TN, and Clay content are the main factors influencing K. Furthermore, it is possible that GMD can better reflect the sediment yield of loess texture erosion58. Given that soil erodibility is primarily determined by soil texture, mineralogy, and organic matter, and that GMD represents the size and distribution of soil granulometrics, it is evident that a decrease in K is positively correlated with higher soil aggregate stability. GMD is a more practical method for estimating soil erosion59, which can be employed to measure soil erosion resistance. Clay has a good protective and accumulation effect on soil organic carbon60, which is mainly reflected in the large specific surface area and charge density of soil clay particles, which have a strong adsorption capacity for soil organic carbon. Moreover, it can form relatively stable organic-inorganic complexes with macromolecular organic substances, and these complexes can also form more stable aggregate structures to enhance the accumulation of organic carbon61, and most results show that increasing the content of clay and nutrients in the soil can prevent soil erosion62. The correlation further showed that the content of > 0.25 mm aggregates, SOC, TN, and CLA also had a strong positive association with the stability of soil aggregates, which is consistent with the results of An et al.63. The stability of soil aggregates can serve as a “bridge” for other influencing factors that affect K, and 0.25 mm aggregates seem to be an appropriate indicator to assess the effect of vegetation restoration on soil aggregates. In addition, TN had significant effects on soil stability in this research, which may be due to the fine composition of soil granulometrics in the gully head. TN in the soil can promote the formation of more stable chemical bonds between soil granulometrics, and an increase in the soil’s nitrogen level could accelerate the synthesis and accumulations of organic matter64, both of which work together to improve the shear resistance of soil and reduce the risk of soil erosion under external forces, thus inhibiting soil erosion. Phosphorus content had little effect on the erodibility of the soil, possibly due to the reality that phosphorus is a sedimentary element and is primarily influenced by the parent material65. Among them, the phosphorus content of HR plantation leaves and soil is high, and planting sea-buckthorn can improve soil microbial activity and promote phosphorus absorption66; high-phosphorus soil also increases the sensitivity to pests and diseases. Although most HR varieties grow well in this area, they suffer from serious pests and diseases. Their growth period was short, and the overall soil improvement effect was poor.

Conclusions

In the loess hilly and gully region, soil samples were collected from five types of vegetation restoration and three soil layers in the head of a branch gully, and the stability and erodibility of soil aggregates were evaluated. The aggregates were primarily microaggregates, and the content of large aggregates of mechanically stable PT and NG was high; however, the macroaggregates of grassland were fragile to water and had poor water stability, which further indicated that water-stable aggregates were more representative in reflecting the stability of aggregates in gully head vegetation restoration in Loess hilly and gully regions. The stability and nutrients of soil aggregates were the highest in arbors, followed by shrubs, and the worst in grassland. The GMD was used to characterize soil erosion resistance. Increasing SOC and TN could inhibit soil erosion and reduce soil erodibility, and vegetation with high soil clay content could effectively prevent soil erosion. In general, appropriate agricultural and engineering measures should be taken to effectively inhibit the advancement of the gully head in this watershed, and planting PT and PS is an ideal choice for gully head management in the future.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Poesen, J. Soil erosion in the Anthropocene: Research needs. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 43, 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4250 (2018).

Blake, W. H. et al. A deconvolutional bayesian mixing model approach for river basin sediment source apportionment. Sci. Rep. 8, 13073. (2018).

Zhao, G., Mu, X., Wen, Z., Wang, F. & Gao, P. Soil erosion, conservation, and ecoenviro-nment changes in the Loess Plateau of China. Land Grad. Dev. 24, 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2246 (2013).

Poesen, J., Nachtergaele, J., Verstraeten, G. & Valentin, C. Gully erosion and environmentalchange: importance and research needs. Catena 50 (02), 91–133 (2003).

Shi, Z. et al. Channel erosion dominates sediment sources in an agricultural catchment in the Upper Yangtze basin of China: evidence from geochemical fingerprints. Catena 199, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.105111 (2021).

Liu, J. & Liu, H. Soil erosion changes during the last 30 years and contributions of gully erosion to sediment yield in a small catchment, southern China. Geomorphology 368 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107357 (2020).

Belayneh, M., Yirgu, T. & Tsegaye, D. Current extent, temporal trends, and rates of gully erosion in the Gumara watershed, Northwestern Ethiopia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 24, e01255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01255 (2020).

Wang, B. et al. Effect of natural restorationtime of abandoned farmland on soil detachment by overland flow in the Loess Plateau of Ch-ina. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 38, 1725–1734. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3459 (2013).

Guo, M. M., Wang, W. L., Wang, T., Wang, W. X. & Kang, H. Impacts of different vegetation restoration options on gully head soil resistance and soil erosion in loess tablelands. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 45, 1038–1050. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4798 (2020).

Zhu, Y. et al. Revegetation-induced changes in vegetation diversity improve soil propertiesof gully heads. Sci. Total Environ. 889, 164214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164214 (2023).

Bronick, C. J. & Lal, R. Soil structure and management: a review. Geoderma 124, 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.03.005 (2005).

Yao, Y. et al. Response of aggregate associated organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous to re-vegetation in agro-pastoral ecotone of northern China. Geoderma 341, 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.01.036 (2019).

Baranian Kabir, E., Bashari, H., Mosaddeghi, M. R. & Bassiri, M. Soil aggregate stability and organic matter as affected by land-use change in central Iran. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 63, 1823–1837. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2017.1308492 (2017).

Bissonnais, L. et al. Soil aggregate stability in Mediterranean and tropical agro-ecosystems:effect of plant roots and soil characteristics. Plant Soil 424, 303–317. (2018).

Zhu, D. et al. Afforestation influences soil aggregate stability by regulating aggregate tran-sformation in karst rocky desertification areas. Forests 14, 1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071356 (2023).

Usman, S., Singh, S. P., Rawat, Y. S. & Bargali, S. S. Fine root decomposition and nitrogenmineralisation patterns in Quercus leucotrichophora and Pinus roxburghii forests in central Hi-malaya. Ecol. Manag. 131 (99), 191–199. (2000).

Wang, L., Zhang, G., Zhu, P. & Wang, X. Comparison of the effects of litter covering a-nd incorporation on infiltration and soil erosion under simulated rainfall. Hydrol. Process. 34, 2911–2922. (2020).

Zhang, Q., Shao, M., Jia, X. & Zhang, C. Understory vegetation and drought effects on soil aggregate stability and aggregate associated carbon on the Loess Plateau in China. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 82, 106–114. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2017.05.0145 (2018).

Zhao, C., Jia, X., Zhu, Y. & Shao, M. Long-term temporal variations of soil water conte-nt under different vegetation types in the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 158, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2017.06.006 (2017).

Dong, L. et al. Effects of vegetation restoration types on soil nutrients and soil erodibilityregulated by slope positions on the Loess Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 302 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113985 (2022).

Liu, R., Wang, D. & Soil, C. N, P and K stoichiometry affected by vegetation restoration patterns in the alpine region of the Loess Plateau, Northwest China. PloS ONE 15, e0241859. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241859 (2020).

Shinjo, H., Fujita, H., Gintzburger, G. & Kosaki, T. Soil aggregate stability under differe-nt landscapes and vegetation types in a semiarid area in northeastern Syria. Soil Sci. Plant. Nutr. 46, 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380768.2000.10408778 (2000).

Chen, S., Zhang, G., Zhu, P., Wang, C. & Wan, Y. Impact of slope position on soil erod-ibility indicators in rolling hill regions of northeast China. Catena 217, 106475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106475 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Effect of land use conversi-on on soil organic carbon sequestration in the loess hilly area, loess plateau of China. Ecol. Res. 22, 641–648. (2007).

Demenois, J., Carriconde, F., Rey, F. & Stokes, A. Tropical plant communities modify soil aggregate stability along a successional vegetation gradient on a ferral sol. Ecol. Eng. 109, 161–168. (2017).

Guo, M., Wang, W., Kang, H. & Yang, B. Changes in soil properties and erodibility of gully heads induced by vegetation restoration on the Loess Plateau, China. J. Arid Land. 10, 712–725. (2018).

Zhao, H., He, H., Wang, J., Bai, C. & Zhang, C. Vegetation restoration and its environm-ental effects on the Loess Plateau. Sustainability 10, 4676. (2018).

Vanmaercke, M. et al. How fast do gully head cuts retreat? Earth Sci. Rev. 154, 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.01.009 (2016).

Kompani-Zare, M., Soufi, M., Hamzehzarghani, H. & Dehghani, M. The effect of some watershed, soil characteristics and morphometric factors on the relationship between the gully volume and lengthin Fars Province, Iran. Catena 86, 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2011.03.008 (2011).

Devroede, J., Duchateau, R. & Koning, C. E. The synthesis of poly (butylene terephthalate) from terephthalic acid, part II: Assessment of the first stage of the polymerization process. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 114, 2427–2434. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.30781 (2009).

Gale, M. R. & Grigal, D. F. Vertical root distributions of Northern tree species in relation to successional status. Can. J. Res. 17, 829–834. https://doi.org/10.1139/x87-131 (1987).

Hodge, A. The plastic plant: root responses to heterogeneous supplies of nutrients. New Phytol. 162, 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01015.x (2004).

Tang, X. et al. Responses of soil aggregate stability to organic C and total N as controll-ed by land use type in a region of South China affected by sheet erosion. Catena https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106543 (2022).

Elliott, E. T. Aggregate structure and Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus in native and cul-tivated soils. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 50, 627–633. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1986.03615995005000030017x (1986).

Dou, Y., Yang, Y., An, S. & Zhu, Z. Effects of different vegetation restoration measures on soil aggregate stability and erodibility on the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 185, 104294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2019.104294 (2020).

Katz, A. J. & Thompson, A. H. Fractal sandstone pores: implications for conductivity and pore formation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 54, 1325–1328. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.1325 (1985).

Shirazi, M. A. & Boersma, L. A unifying quantitative analysis of soil texture. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 48, 142–147. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1984.03615995004800010026x (1984).

Williams, J. R., Renard, K. G., Dyke, P. T. & EPIC A new method for assessing erosion’s effect on soil productivity. J. Soil. Water Conserv. 38 (5), 381–383 (1983).

Six, J., Elliott, E. T. & Paustian, K. Soil structure and soil organic matter II. A normalizedstability index and the effect of mineralogy. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 64, 1042–1049. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2000.6431042x (2000).

Zhu, S. et al. Cover cropping promotes soil carbon sequestration by enhancing microaggr-egate protected and mineral-associated carbon. Sci. Total Environ. 908, 168330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168330 (2024).

Jiao, F. X., Hou, W. L. & Li, G. L. Study on soil cementation and aggregate distribution characteristics under rainfall conditions. Res. Soil. Water Conserv. 31 (06), 109–118 (2024).

Wang, D., Li, G. L., Fu, Y., Gao, G. X. & Zheng, T. H. Detachment and transport character-istics of sandy loam soil by raindrop action in the northern Loess Plateau, China. J. Soil. Water Conserv. 73, 705–713. https://doi.org/10.2489/jswc.73.6.705 (2018).

Issa, O. M. et al. Soil detachment and transport on field- and laboratory‐scale interrill areas: erosion processes and the size‐selectivity of eroded sediment. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 31, 929–939. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.1303 (2006).

Swanson, N. P., Dedrick, A. R. & Weakly, H. E. Soil particles and aggregates transported in runoff from simulated rainfall. Trans. ASA 8, 437–437. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.40541 (1965).

Wang, B. et al. Effects of vegetation restoration on soil aggregates, organic carbon, and nitrogen in the Loess Plateau of China. Catena 231, 107340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107340 (2023).

Wang, B., Zhang, G. H., Shi, Y. Y., Li, Z. W. & Shan, Z. J. Effects of near soil surface cha-racteristics on the soil detachment process in a chronological series of vegetation restoration. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 79, 1213–1222. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2015.03.0120 (2015).

Wang, B. & Zhang, G. H. Quantifying the binding and bonding effects of plant roots on soil detachment by over and flow in 10 typical grasslands on the Loess Plateau. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 81, 1567–1576. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2017.07.0249 (2017).

Ma, C., Luo, Y., Shao, M. & Jia, X. Estimation and testing of linkages between forest structure and rainfall interception characteristics of a Robinia pseudo acacia plantation on China’s Loess Plateau. J. Res. 33, 529–542. (2022).

Zhu, B., Li, Z., Li, P., Liu, G. & Xue, S. Soil erodibility, microbial biomass, and physical chemical property changes during long-term natural vegetation restoration: a case study in the Loess Plateau, China. Ecol. Res. 25, 531–541. (2010).

Padbhushan, R., Rakshit, R., Das, A. & Sharma, R. P. Effects of various organic amendments on organic carbon pools and water stable aggregates under a scented rice–potato–onion cropping system. Paddy Water Environ. 14, 481–489. (2016).

Schaller, F. W. & Stockinger, K. R. A comparison of five methods for expressing aggregati-on data. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 17, 310–313. (1953).

Thompson, J. et al. Land use history, environment, and tree composition in a tropical for-est. Ecol. Appl. 12, 1344–1363. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2002)012 (2002).

Chen, Z. X., Guo, M. M., Wang, W. L., Wang, W. X. & Feng, L. Response of soil erodibilit-y of permanent gully heads to revegetation along a vegetation zone gradient in the loess-tableand gully region of the Chinese Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 892, 164833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164833 (2023).

Li, Z. W., Zhang, G. H., Geng, R., Wang, H. & Zhang, X. C. Land use impacts on soildeta-chment capacity by overland flow in the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 124, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2014.08.019 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Effects of different hedgerow patterns on the soil physicochemical properties, erodibility, and fractal characteristics of slope farmland in the Miyun Reservoir area. Plants 11, 2537. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11192537 (2022).

Chen, H., Koopal, L. K., Xiong, J., Avena, M. & Tan, W. Mechanisms of soil humicacida-dsorption onto montmorillonite and kaolinite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 504, 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2017.05.078 (2017).

Erktan, A. et al. Increase in soil aggregates stability along a Mediterranean successional gradient in severely eroded gully bed ecosystems: combined effects of soil, root t.raits and plant community characteristics. Plant Soil 398, 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2647-6 (2016).

Sheng, H. W., Cai, Q. G. & Sun, L. Y. Impacts of loessial texture on slope erosion. China J. Soil. Water Conserv. 30 (1), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.13870/j.cnki.stbcxb.2016.01.007 (2016).

Sun, L. Y., Fang, H. Y., Qi, D. L., Li, J. L. & Cai, Q. G. A review on rill erosion process and its influencing factors. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 23, 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-013-0612-y (2013).

Liu, R., Ma, T., Qiu, W. K. & Liu, Y. J. Distribution characteristics of particle size and organic carbon in clay sediments in Jianghan plain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42 (04), 194–120 (2019).

Ren, X. E. et al. Effects of temperature on organic carbon mineralization in paddy soils with different clay content. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. (10) 2245–2250 (2007).

Huang, S., Rui, W., Peng, X., Huang, Q. & Zhang, W. Organic carbon fractions affected by long-term fertilization in a subtropical paddy soil. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 86, 153–160. (2010).

An, S. S., Huang, Y. M., Zheng, F. L. & Yang, J. G. Aggregate characteristics during natural revegetation on the Loess Plateau. Pedosphere 18, 809–816. (2008).

Wei, S. et al. A transcriptional regulator that boosts grain yields and shortens the growth duration of rice. Science 377, eabi8455. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi8455 (2022).

Kooijman, A. M., Jongejans, J. & Sevink, J. Parent material effects on mediterranean woodland ecosystems in NE Spain. Catena 59, 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2004.05.004 (2005).

Luo, R. et al. Seasonal dynamics of soil microbial community and enzyme activities in hippophae rhamnoides plantation. China J. Appl. Ecol. 29 (04), 1163–1169. (2018).

Acknowledgements

The Intelligent Soil and Water Conservation Technology in the Loess Hilly and Gully Region Science and Technology Plan Project of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region provided funding for this work (No.2021 GG0070). We acknowledge the language support provided by LetPub (www.letpub.com) in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Y. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by J.W., and Y.M., X.G., N.L. The first draf of the manuscript was written by J.W., and Z.C., Z.W., N.W contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.The resources of this program were provided by H.D. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the fnal manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J., Yang, G., Ma, Y. et al. Effects of vegetation restoration on soil aggregate characteristics and soil erodibility at gully head in Loess hilly and gully region. Sci Rep 14, 31149 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82469-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82469-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Vegetation-induced hydrodynamic alterations on convex slopes: Mechanisms of flow resistance and erosion control

Journal of Mountain Science (2025)