Abstract

Craving is a key symptom of nicotine addiction, driving the urge to seek cigarettes. It is often strongly influenced by social and environmental cues associated with the typical use of the substance. In both clinical and laboratory setting, craving can be experimentally triggered using cue reactivity paradigms, where nicotine-related cues are presented to evoke, and then assess, the desire to smoke. In the last few years, virtual reality (VR) has begun to attract a lot of interest in recreating realistic simulations to investigate craving through cue-reactivity exposure. However, a direct comparison between VR and non-immersive devices (e.g. 2D images presented using monitor) regarding their effectiveness in triggering cravings is still missing. In this study, we investigated differences in craving responses by comparing immersive and non-immersive nicotine-related cue-reactivity paradigms. A group of smokers (N = 23, F = 15, Mage = 23.2y.o.) and non-smokers (N = 22, F = 13, Mage = 23.7y.o.) participated in two sessions of cue reactivity exposure, featuring neutral and smoking-related scenarios presented through VR (immersive) and 2D display images (non-immersive). Each session included recording of physiological activity (skin conductance level), self-reported cigarette craving, and an assessment of the overall quality of the experience. Results showed that smokers experienced increase in cigarette cravings after exposure to nicotine-related cues compared to neutral scenarios. Moreover, self-report craving was higher after the VR cue reactivity compared to the 2D modality. A positive relationship between scores in the nicotine dependence questionnaire and self-report craving during VR cue-reactivity session was found, but not for the non-immersive session. Regarding physiological responses, smokers exhibited significantly higher skin conductance levels compared to non-smokers during the VR cue reactivity session. In contrast, no significant differences between the two groups were observed during the 2D display exposures. Participants evaluated the VR paradigm as more realistic tool to recreate credible simulations of real-life situations, and a positive correlation between self-reported craving and vividness of experience was found in the smokers’ cohort. The present study provides further elements supporting the use of VR in the cue-reactivity paradigm for craving assessment, compared to non-immersive devices. Future studies will aim to confirm the effectiveness of VR as a better tool in assessing craving during clinical treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Craving is generally defined as an intense preoccupation and desire to intake substances (and/or perform certain behaviors, as well as drug-seeking behavior) and can be considered one of the main symptoms of substance use disorders (SUD)1,2. Craving is well known in the psychological literature as a central aspect of both the assessment and treatment of SUD, as well as a predictive factor of relapse after treatment3,4. The role of craving in inducing seeking behavior and motivation to consume drugs has been extensively investigated to uncover the primary challenges individuals face in overcoming addictions5,6. In fact, one of the main difficulties in treating craving is related to the reactivity to drug-related stimuli, for which contexts or situations associated with drug intake evoke a strong desire for drug intake and a relative-seeking behavior7. This mechanism seems to be based on reinforcement conditioning, for which drug-related cues repetitively associated with drug consumption can become salient stimuli and predict future rewards8,9,10. To obtain a quantitative measure of craving, cue-reactivity paradigms are widely used in addiction diagnosis and assessment11,12,13. During cue reactivity tasks, participants are exposed to several pictures or videos related to drug/substance-related cues or specific environmental contexts14, which somehow recall the use of the substance. Such exposition can be unisensory or multisensory, being based on visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory stimuli15. Cue-reactivity-induced craving is often measured by self-report scales, but neurophysiological and physiological responses are also observed during stimulus presentation13. Thus, the psychophysiological activation (indexed by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system) probably reflects the desire to consume (or interact with) the substance when the participant is exposed to drug-related cues, especially if presented during abstinence state16,17,18,19,20.

Nowadays, Virtual Reality (VR) has attracted much interest as a cutting-edge and promising tool for recreating vivid and realistic exposure experiences21,22. VR allows us to create an immersive experience in which participants can be immersed in a given virtual environment and act similarly as in the real world. This is most likely due to ‘the sense of presence’, defined as the sense of being there in the virtual environments23,24. As a matter of fact, immersion can be a relevant component for improving the capability of experimental settings to generate reliable behavioral and psychophysiological responses to the stimuli presented25. This is particularly relevant in the case of cue-reactivity paradigms, where the main goal is to evoke a craving state as more realistic and ecological as possible in a similar manner to real-life situations. For these reasons, virtual and augmented environments have been used to simulate drug-related situations, especially in terms of social and contextual factors associated with substance intake26,27. As in the classic cue-reactivity paradigms, the participants’ craving was assessed through physiological variables (i.e. Electrodermal activity- EDA, heart activity- HR or HRV and cortisol) or by self-report responses (i.e. Visual Analogue Scales—VAS). Over the last 25 years, the use of VR in inducing craving was used to investigate different forms of addiction: alcohol28, nicotine29, cannabis30, cocaine31, methamphetamine16, or polyaddiction32, offering new opportunities to study addictive behaviors . Among these , nicotine craving is one of the most investigated behaviors through VR, both in terms of assessment evaluation and treatment outcomes27,33,34,35. Previous works were focused on smokers’ attentional bias for smoking cues36, the role of context in inducing craving37, the cue features able to increase craving response32,38, or craving differences between treatment vs. non-treatment seeking participants39. Recently, neurophysiological markers of nicotine craving were also investigated by using VR40.

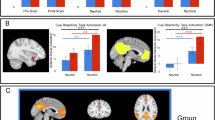

Despite the number of studies that have already used VR to assess nicotine-craving, there is no robust evidence about the beneficial role of VR, as compared to the classic device (i.e. Monitor Screen), in assessing craving after cue-reactivity exposure. Pericot-Valverde found a comparable effect size in craving magnitude comparing VR to more classical models41. As well, the first applications of VR in smoking cessation treatment are promising33. However, whether VR is more able to induce nicotine craving than a non-immersive device is an open question. To our knowledge, only two studies directly compared VR to non-immersive presentation modalities to induce nicotine craving in smokers, performed in the early 2000s, which nowaday is outdated VR technology42,43. These studies reported a significantly greater craving response using the immersive compared to a non-immersive version of the same cue-reactivity paradigm, and differences in brain activity during VR exposure compared 2-D monitor. However, it is worth noting that the sample size used in these studies was very limited (a between-group design with 22 male participants in the first one and 8 participants in the fMRI study). Additionally, VR technology has significantly advanced in the design and modeling of virtual environments. Based on the current evidence, it is hard to conclude the effectiveness of VR cue reactivity paradigms against nicotine craving, and further investigations are certainly required44.

This study aims to provide stronger evidence of VR’s effectiveness in craving assessment by evaluating differences in nicotine craving among smokers exposed to cue-reactivity paradigms in immersive vs. non-immersive modalities. We validated the paradigm (neutral vs. nicotine scenarios) using an independent sample of smokers and non-smokers before starting the experiment. Craving assessment in each session included physiological (SCL) and self-report (VAS) measurements. We hypothesized increased nicotine craving (VAS) after the VR compared to the 2-D images cue-reactivity session. We also expected increased physiological response in smokers but not in non-smokers in both sessions. The key question, however, is whether the two modalities (VR vs. 2D) differently evoke arousal responses in the smoker sample. We recruited a control group of non smokers to compare physiological activity obtained from smokers cohort among the two scenarios and modalities Additionally, scores from the nicotine-dependence questionnaire were collected to correlate with self-reported cravings across both immersive and non-immersive conditions. We conducted further analyses on the reported vividness and realism of the experiences in the two cue-reactivity modalities among smokers and non-smokers. Lastly, we perform supplementary analyses (see supplementary materials) related to the smoke history and the gender influence on the comparison of nicotine self-report craving induced by VR vs. 2D cue-reactivity exposure.

Results

Validation of the stimuli

A total of 17 participants (smokers = 10) were enrolled for the stimuli validation of the study. A 10-point VAS scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely) was used to rate the “sense of being in a scenario with nicotine cues” after the neutral and smoke scenario presentations. A linear mixed model analysis was used to validate the two scenarios with the main factor of scenario (neutral vs. smoke) and participants (smoker vs. non-smoker) and ID set as a random intercept. A significant effect of scenario (F(1,15) = 97.74, p < 0.001) was found, revealing that the sense of being in a scenario with nicotine cues was higher in the smoke scenario compared to the neutral scenario (difference 5.23). No main effect of smoker (F(1,15) = 0.74, p = 0.349) or interaction effect scenario * smoker (F(1,15) = 0.55, p = 0.467) were found, suggesting that the neutral and nicotine scenarios adopted were similarly judged among smokers and non-smokers (Fig. 1).

Participants

A total of N = 45 participants aged between 18 and 53 years took part in the experiment (M = 23.4, SD = 1.91). There were twenty-eight Females (62.2%) and eighteen Males (37.8%) (Chi-Squared test: X2 = 2.69, p = 0.101). Twenty-three participants were non-treatment-seeking smokers (50.5%, F = 15) and twenty-two non-smokers (49.5%, F = 13). Among smokers, most of these were long-time smokers (more than five years = 78.3%, more than one year = 21.7%, less than one year = 0%, Chi-Squared test: X2 = 7.35, p = 0.007) and reported nicotine craving also in indoor spaces (82.6%). Time since the last cigarette assessment indicated a 3 h of withdrawal in 56.2% and 2 h in 43.8% of the experimental exposure sessions. Less than half of the participants reported previous experience with Virtual Reality (48.8%).

Self-report craving

Here, we exclusively present the result from the sample of smokers, considering that no effect was driven by the non-smoker group on self-reported cravings. The comprehensive analysis, encompassing a comparison between smokers and non-smokers, is documented in supplementary materials. Self-report craving was submitted to a 2 (scenario: neutral vs. smoke) X 2 (device: 2D-display images vs. VR) linear mixed model (ID random). A significant main effect of scenario was found regarding self-reported craving (F(1,66) = 28.56, p < 0.001), which confirms more craving induced by the smoke scenario as compared to the neutral scenario (difference = 1.54). A significant main effect of device (F(1,66) = 6.17, p = 0.016) was also found. Indeed, VR exposure induced a higher craving level than 2D exposure (difference = 0.71). The significant interaction effect between scenario * device was non-significant (F(1,66) = 0.005, p = 0.940), indicating that the neutral scenario always induces less craving than the smoke scenario, both in VR and 2D display exposure (Fig. 2).

Skin conductance level (SCL)

The mean value of the skin conductance level (SCL) during each scenario was submitted to a 2 (scenario: neutral vs. smoke) X 2 (device: 2D display images vs. VR) X 2 (participants: smokers vs. non-smokers) linear mixed model (ID random and baseline as a covariate). The main effect of scenario was not significant (F(1,170) = 2.10, p = 0.148). The main effect of device was significant (F(1,170) = 5.75, p = 0.017), with high level of SCL during the VR exposure compared to 2D modality (difference = 0.27 μS). The main effect of smoker (F(1,170), p = 0.028) was significant, with higher SCL in smokers compared to non-smokers participants (difference = 0.24 μS). Notably, we found a significant interaction effect between device * smoker (F(1,170), p = 0.011). The post-hoc analysis revealed that smokers showed a higher skin conductance level in VR compared to their session based on 2D images (difference = 0.56 μS, p(Bonferroni) = 0.003) and compared to the non-smokers, both in the VR (difference = 0.54 μS, p(Bonferroni) = 0.005) and 2D display-based (difference = 0.52 μS, p(Bonferroni) = 0.010) setting. In other words, smokers exhibited stronger physiological responses during cue-reactivity in virtual reality compared to 2D modality, and regardless the modality, compared to the non smokers . The two-way interactions scenario * device (F(1,170) = 2.96, p = 0.087) and scenario * smoker (F(1,170) = 0.78, p = 0.376) was not significant. The three-way interaction scenario * smoker * device (F(1,170) = 0.96, p = 0.327) was not significant too (Fig. 3).

Quality of experience

The reported score in the VAS scale for the item ‘Visual realism of experience’ and ‘Sense of presence’ was submitted to two separate 2 (device: 2D display images vs. VR) X 2 (participants: smokers vs. non-smokers) linear mixed model (ID random and baseline as a covariate).

Visual realism of experience

Data from one participant was not included due to a missing answer. A significant effect of the device (F(1, 131.3) = 66.50, p < 0.001) was found regarding the visual realism of the experience. As expected, VR elicited a greater sense of visual realism than 2D images (difference = 1.72). The main effect of smokers was significant (F(1, 43.3) = 4.13, p = 0.048), revealing that smokers reported higher visual realism compared to non-smokers. Critically, the interaction effect of device * smoker (F(1, 131.3) = 12.70, p < 0.001) was significant . The interaction effect is explained by the higher level of visual realism reported from the smokers’ cohort after the non-immersive exposure, which resulted significantly higher from the scores reported after the same modality in non-smokers (difference = 1.60, p(Bonferroni) = 0.007). In both groups, the VR exposure elicited a higher level of visual realism compared to 2D display-based exposure (difference in smokers’ cohort = 0.97, p(Bonferroni) = 0.008, difference in non-smokers’ cohort = 2.48, p(Bonferroni) < 0.001). Conversely, the score reported by the smokers after the non-immersive session was not statistically different from the score of non-smokers after the VR session (difference = -0.88, p(Bonferroni) = 0.377) (Fig. 4-left panel).

Sense of presence

Data from two participants were not included due to a missing answer.

A significant effect of device (F(1, 131.4) = 89.67, p < 0.001) was found regarding the participants’ sense of presence, indicating that VR elicited a greater sense of presence compared to 2D images (difference = 2.06). A significant effect of smokers was also found (F(1, 43.5) = 5.59, p = 0.023), revealing that smokers reported a higher level of presence in smokers than in non-smokers (difference = 1.06). Once again, the interaction effect between device * smoker (F (1, 131.4) = 5.59, p = 0.023) was significant. Similar to the previous results on the visual realism of the experience, smokers reported a higher level of presence compared to non-smokers after the 2D display-based exposure (difference = 1.74, p(Bonferroni) = 0.005). In both groups, the VR session elicited a higher level of presence compared to the non-immersive session (difference in smokers’ cohort = 1.37, p(Bonferroni) < 0.001, difference in non-smokers’ cohort = 2.75, p(Bonferroni) < 0.001). Finally, the score reported in the smoker cohort after the 2D display session was not statistically different from the score reported by non-smokers after the VR task (difference = − 1.00, p(Bonferroni) = 0.281) (Fig. 4- right panel).

Correlation analysis

Relationship between Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (FNDT) scores and self-report craving

The first correlation concerned the relationship between self-reported craving and the score in the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), separately for the VR and the 2D display-based session. This analysis encompassed only smoker participants. A significant correlation between the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) scores and self-report craving score revealed a positive association only in the case of VR modality (R = 0.3, p = 0.044), while the same trend was not found in the case of 2D images (R = 0.14, p = 0.36). Indeed, FTND scores positively correlated with the craving reported after the cue-reactivity paradigm (positive correlation, i.e., a higher score in the questionnaire, higher craving after cue-reactivity) only for the VR and not for the 2D display session (Fig. 5).

Relationship self-report craving and skin conductance level during the cue-reactivity paradigm

In the smoker cohort, a positive trend was observed between the self-reported craving score and the skin conductance level (R = 0.18, p = 0.078), although it did not reach statistical significance. This trend partially suggests that smokers reporting higher levels of craving tended to exhibit higher skin conductance levels (Fig. 6).

Relationship between self-report craving, presence, and visual realism during the cue-reactivity paradigm

We measured the correlation between the quality of experience and the craving response in the smokers and non-smokers cohort. Reported craving was positively correlated with the visual realism of experience (R = 0.31, p = 0.003) and the sense of presence (R = 0.27, p = 0.011) only in the smoker cohort. This result showed that among smokers, a greater sense of presence and visual realism during the experience were both associated with higher levels of reported craving (Fig. 7).

Discussion

The present study investigated differences in nicotine craving induced by a cue-reactivity paradigm, comparing the outcome when the paradigm was presented by means of an immersive (VR) vs. a non-immersive (2D display images presented using a monitor) modality. The craving assessment included both physiological (during) and self-report craving (after) responses to neutral (without explicit nicotine related cues) and cigarette related scenarios. To disentangle the physiological activation during both paradigms, the physiological data obtained by the smoker sample were compared to a control group of non-smokers who performed the same task in VR vs. 2D images modality. To our knowledge, this is the first study that directly compares nicotine craving responses (physiological and self-report) in smokers and non-smokers using immersive and non-immersive devices in the same experimental sample.

As the first result, this study showed differences in craving among smokers after exposure to an environment characterized by smoke-cue-related stimuli. The smoke scenario with explicit cues elicited higher craving responses, measured by the self-report desire to smoke, compared to the neutral scenario. This result was fairly expected based on previous studies, which consistently demonstrated an increase in nicotine craving after exposure to an environment characterized by explicit cues related to smoking activities (ashtray, packet of cigarettes) compared to an environment in which such elements were missing17,32,37,38.

Beyond that, the primary aim of this study concerned the effectiveness of immersive devices, such as Virtual Reality, in inducing more robust craving responses compared to a non-immersive exposure modality. Given the quick relapse for most smokers treated, improving the assessment tools should enhance positive outcomes during and after treatments45. One of the current limits in the cue-reactivity paradigm is related to the lack of correlation between laboratory settings and real-life situations46. For this reason, VR has started to be considered a valid instrument to induce craving in several addictive disorders, and more often used in assessing and treating addictive disorders. Compared to non-immersive modality, the main advantage of VR cue-reactivity is the ability to induce more ecological and reliable responses in the environment to which the participant is exposed47. This consideration is supported by increased studies, starting with the new century, that include cue-reactivity parading in immersive environments (see Ref.26 for a recent review on VR in assessing and treating addiction disorders). The result of our study would seem to confirm this insight, at least for nicotine craving, showing differences in craving response among the two exposure modalities (immersive vs. non-immersive cue-reactivity paradigm). Indeed, smokers reported higher levels of craving after VR than in the 2D display modality. Furthermore, we found a positive correlation between the craving induced by the cue-reactivity session and the scores in the nicotine dependence questionnaire, but only following VR exposure, where a higher score in the nicotine dependence questionnaire led to a more intense craving response to the cue-reactivity paradigm. Indeed, based on our findings, VR increases nicotine craving compared to non-immersive images for the neutral and smoke scenarios presented. As far as this point is concerned, it’s important to highlight that even though there were no direct nicotine cues, the neutral scenario contained immersive scenes of open spaces that could potentially elicit a desire for cigarette, particularly in case of long-lasting periods of cigarette abstinence.

The innovative aspect of our study relates to the fact that we also included the measurement of physiological variables for comparing immersive and non-immersive exposure. This aspect is extremely relevant given that in nicotine craving (and in craving in general), the presentation of cue-related stimuli seems associated with changes in the responses of the autonomic nervous system, as demonstrated by previous cue-reactivity paradigm studies18,20,31,48,49. Despite the relationship between physiological measurement and nicotine craving is still a matter of debate45, the most recent meta-analysis on cue-reactivity in tobacco cigarette smokers, suggested that skin conductance (an index of electrodermal activity), among physiological parameters, is currently the most reliable marker of craving in nicotine cue-reactivity44. Thus, including this kind of measurement in craving assessment allows for a further measure of uncomforted states during the cue-reactivity assessment (and, more generally, to overcome the limitations of more explicit/subjective measures). In order to compare the result obtained by the smoker sample among the two exposure modalities, an independent sample of non-smokers was included as the control group, following the same experimental procedure18. Our study showed increased physiological activation (measured by the level of skin conductance, o SCL) in smokers during the cue-reactivity presented in Virtual Reality, compared to the non-immersive modality. On the contrary, the non-smoker group did not present a difference in SCL comparing immersive and non-immersive exposure. Based on our result, physiological responses were similar among smokers and non-smokers in the 2-D image setting. On the other hand, during the VR cue-reactivity paradigm, smokers showed increased skin conductance levels compared to the non-smoker sample (both VR and 2D display based images) and to the same scenes presented in non-immersive modality. Finally, we found partial evidence of a relationship between skin conductance and self-reported cravings, though this trend did not reach statistical significance. This result might be taken to suggest that the link between explicit craving reports and implicit physiological responses may not be entirely linear. The high variability in physiological responses across participants, likely influenced by individual differences in autonomic system activity, may have contributed to this outcome. Further research is needed to clarify the relationship between nicotine cravings and skin conductance during cue exposure.

By a number of supplementary analyses (see supplementary materials), our study also revealed that other factors, such as the gender of the participants and their smoking history, may play an important role in inducing nicotine craving by means of immersive and non-immersive cue-reactivity stimulation. As far as gender differences in craving response are concerned, previous studies reported that female participants evidenced greater nicotine craving in the case of smoking abstinence and negative emotion exposure, resulting in more responsiveness to the cue-reactivity paradigm50,51. Although we did not find evidence for gender effects on self-reported craving, female participants showed a stronger craving response to VR compared to 2D display images presentation, while such a difference was not appreciated in male participants. Furthermore, we found that individuals with a long history of smoking (over 5 years) exhibited a more pronounced disparity in craving levels induced by VR presentations compared to 2D images. Regarding this aspect, a recent meta-analysis reported an inverse relationship between smoke history and craving responses during cue-reactivity paradigms: a longer smoking history correlated with a lower response after cue reactivity presentations52. The authors interpreted this result as reflecting a ceiling effect to cue reactivity paradigm in long-time smokers. However, it is interesting to note that, in the present study, long-term smokers were found to be more susceptible to reporting higher cravings in immersive environments compared to non-immersive ones. This finding may suggest that the impact of using immersive devices for craving induction via the cue-reactivity paradigm could be stronger among long-term smokers, questioning whether such a ceiling effect is generalized across cue-reactivity presentation modalities.

Overall, these results are likely to be related to the quality of exposure experience evoked by immersive VR as compared to non-immersive images presented using a 2D display monitor. In fact, using self-report measures, we showed that both smokers and non-smokers reported a larger increase in the sense of presence and realism of experience for the VR than under 2D image sessions. Additionally, among smokers, the perceived sense of presence and visual realism during exposure showed a positive correlation with reported craving. Interestingly, smokers perceived the 2D environment as more realistic than non-smokers. Attentional bias, defined as the tendency to concentrate on addiction cues selectively, has been observed among smokers when exposed to smoking-related stimuli. This phenomenon has been identified through methods such as eye-tracking attentional orientation or the Stroop task. Additionally, it has been proposed as a predictive factor for relapse following smoking cessation53,54,55. When directly comparing immersive and non-immersive exposure modalities, we observed a perceptual bias among smoker participants regarding the level of visual realism and sense of presence. This bias was indicated by a higher level of presence and visual realism in the non-immersive cue-reactivity presentation compared to the non-smoker cohort. Albeit speculative, this result seems to suggest that smoker participants perceived the non-immersive cue-reactivity modality as more realistically and more immersive. However, given the lack of previous studies that compared immersive vs. non-immersive cue-reactivity, future studies will aim to confirm this result related to the vividness of experiences.

Finally, the evidence provided by this study needs to be also discussed regarding to the psychotherapeutic approaches currently used to treat tobacco addiction. Among these, cue exposure therapies (CET) have been proposed as a therapeutic model for smoking cessation treatments56. CET treatments are based on extinction processes, for which tobacco cues are repeatedly presented in the absence of reward (smoking) to disrupt the association between cues and reward. Moreover, exposure sessions could be integrated with other interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or mindfulness. For these reasons, CET therapy has started to benefit from VR to recreate realistic simulations in which the patients can be immersed in contexts that recall smoke environments33,34,57,58,59. Importantly, extinction is largely context-dependent and rarely extended to other contexts60. In this regard, our paradigm was based on 360° spheric photos (but also 360° spheric videos), which can easily be customized on the basis of environments frequented by the client/patients in order to increase extinction response to specific situations. As far as this point is concerned, a recent meta-analysis on nicotine craving indicated that personalized cues are comparable to non-personalized cues in inducing craving61. However, most of those studies did not use immersive environments, and whether or not the same results can be expected also in highly realistic VR environments is still a matter of debate. Future perspectives on tobacco addiction treatment should integrate VR as an exposure tool, customizing the virtual environments for the patients’ needs in order to maximize treatment intervention and clinical outcomes. In this scenario, ad-hoc contexts are reconstructed for each participant in the treatment, enhancing the overall treatment’s ecological validity.

One of the main limitations that should be considered in this study is related to the sample used. In particular, most of the participants are young students recruited from the university who are familiar with immersive devices. Moreover, all the smoker participants enrolled in the study were non-treatment-seeking smoking cessation. Thus, the effectiveness of VR compared to a non-immersive setting should also be addressed in older cohorts of participants and in treatment vs. non-treatment-seeking smokers. Another limitation regards the repeated session of cue-reactivity using the same stimuli. Although this choice was driven by the need to control the impact of the stimuli in each session, a habituation effect across sessions cannot be excluded. Regarding our secondary analyses, it is worth noting that our sample was not fully counterbalanced in terms of gender and smoke history (see the supplementary material). Future studies should properly investigate the impact of gender and smoke history in immersive and non-immersive cue-reactivity environments. As the last point, although VR based on 360° spheric photos returns to a more realistic environment, it does not allow interaction with the virtual environment, affecting the active role of the participant during the experience.

To conclude, our study suggests that VR cue-reactivity is a valid and promising tool to increase the reliability of participants’ craving assessment compared to more classic non-immersive devices (2-D images using a monitor screen) in non-seeking treatment smokers. Future studies will be necessary to validate the findings in a clinical population and extend the comparison with other substances. Moreover, including neuroimaging measurements (i.e., EEG or fMRI), as well as further physiological parameters (i.e. HR and HRV), will allow us to understand if VR-driven immersive experiences during cue-reactivity paradigms can induce a stronger response in the neural reward system than non-immersive exposures.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 62) were enrolled using the recruitment webpage of the University of Milano Bicocca (www.milano-bicocca.sona-systems.com) and through word-of-mouth. A total of N = 17 participants (smokers = 10, F = 11) aged between twenty and thirty-six (M = 24.6, SD = 2.78) were enrolled for the stimuli validation of the study. A total of N = 45 participants aged between eighteen and fifty-three years took part in the main experiment (M = 23.4, SD = 1.91). We recruited participants aged 18 to 45 years old. The exclusion criteria included a history of psychiatric disorders or a personal or family history of seizures. The inclusion criteria for the smoker cohort required participants to have smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day for the whole past year. For the non-smoker cohort, the inclusion criteria requires that participants should not have smoked at that level for more than 2 weeks at any stage of their life. The study was conducted according to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Department of Psychology, University of Milano Bicocca, local ethical committee. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Descriptive information on the sample size is reported in Table 1; Descriptive information on the FNDT assessment in the smoker group is reported in Table 2.

Stimuli and apparatus

We developed two types of scenes for each exposition based on 360° panoramic photos. The 360° photos were recorded using an Insta360 One X2 camera (https://www.insta360.com/it/product/insta360-onex2). Twelve photos (6 for the neutral and 6 for the smoke scenario) were selected and edited using Adobe Premiere Pro software (https://www.adobe.com) to create a video sequence running at 30 frames per second with a resolution of 5760 X 2880 pixel. The neutral scenario included photos showing outdoor and indoor spaces without explicit nicotine cues (Fig. 8A). The smoking scenario consisted of photos showing outdoor and indoor environments in which explicit nicotine cues (i.e. packets of cigarettes, ashtrays, and cigarettes) were presented (Fig. 8B).

For the non-immersive condition (2D display images), the neutral and the nicotine scenarios were presented on the notebook screen (Asus ROG Strix and a 17.3″ screen with a resolution of 1920 X 1080 pixels) using VLC video player software (https://www.videolan.org/). For the immersive condition, the videos were integrated into two Unity 3D (https://unity.com/) virtual scenarios (neutral and nicotine) and presented using a Meta Quest 2 HMD. The immersive scenes could be explored thanks to the rotational tracking of the head provided by the HMD, while the non-immersive ones could be explored by controlling the point-of-view using the mouse. Each scene consisted of a video presenting a sequence of six 360° spheric photos, and each photo was presented for 30 s. A ten-second black screen divided one environment from the following ones. The same photos and timing, but with different orders of presentation, were used for the immersive and non-immersive sessions.

Skin conductance recording

For the skin conductance level (SCL), signals were recorded at 256 Hz using the Procomp Infiniti 5 (Thought Technology) device and two AgCl electrodes attached to the participant’s index and ring fingers. The SCL was recorded as a continuous measurement, extracting the mean value for the different experimental phases (Baseline, Neutral Scenario, Baseline2, Nicotine Scenario).

Measurements

Demographic information

–Gender, age, and previous experience with virtual reality.

Only for the smoker group

-

Nicotine history: How long have you been a smoker (1 year, 5 years or more).

-

Desire to smoke in close spaces (Yes/No).

-

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND): The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) is one of the most used questionnaires to measure dependency on nicotine. The questionnaire is composed of 8-items, which address the time to the first cigarette in the morning, difficulty in refraining from smoking when is forbidden, the number of cigarettes smoked in a day, difficulty giving up cigarettes in the morning, smoking more in the morning and smoking while ill. For this study, the Italian-validated version of the FTND questionnaire was used to assess dependency on nicotine62. Low dependence is represented by a score of 0–2, low-to-moderate dependence by a score of 3–4, moderate dependence by a score of 5–7, and high dependence by a score of 8. The FTND assessment was measured only before the first cue-reactivity exposure since no differences are expected between the two sessions.

-

Before each session, for the smoker group, the time passed since the last cigarette was assessed using a self-report measurement indicating how long it has been since the last cigarette was smoked (1 h, 2 h, 3 h or more).

Craving self-report

–A 10-point VAS scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 10 (extremely), was administered after the exposition to neutral and nicotine environment (“How much do you want to have a smoke a cigarette now”) in both the 2D display images and the VR session.

Skin conductance level

–The SCL was recorded as a continuous measurement, extracting the mean value for the different experimental phases (Baseline, Neutral Scenario, Baseline2, Nicotine Scenario).

Quality of experience

–Two 10-point VAS scales were administered after the VR and the 2D display session, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 10 (extremely). The assessment concerned the visual realism of experience (“How much have the visual aspects of the environment engaged you?”) and the sense of presence (“I felt immersed in the environment presented”).

General procedure

The participants arrived at the laboratory and signed the informed consent form. At least 2 h of abstinence from smoking were required before the beginning of the experiment for the smoker group. Demographic and self-assessment questionnaires were provided by tablet or computer. After completing all the questionnaires, SCL electrodes were attached to the participant’s index and ring fingers. Participants were instructed to maintain relaxation during the baseline period and freely explore the surrounding environment. No specific instructions were given regarding paying attention to selected objects or parts of the scene. A fixed block of scenario presentation (Neutral as first and Smoke as second) was used to avoid the carry-over effect, according to previous experiments63. Two minutes of baseline were recorded before the first environment was presented. For the participant assigned to the VR experience, the baseline was recorded while wearing the activated HMDs. For the 2D display image modality session, the baseline was recorded while the participant sat in front of the PC monitor that was turned on. Followinf the baseline recording , the neutral scenario was presented to the participant for a duration of 4.10 min. After the presentation of the first environment, the simulation ended, and the participants completed the VAS assessment using the PC. A second baseline was recorded for 2 min before the presentation of the smoke-related environment, which had the same duration as the neutral environment (4.10 min). Self-report evaluations of craving after the smoke scenario and the overall experience evaluation ended the experimental session. The second session was performed at least two weeks after the first one. The order of presentation of the two sessions (in terms of the device and modality used) was counterbalanced between participants (Fig. 9). At the conclusion of the second session, each participant was briefed on the study’s objectives.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by Jamovi software (www.jamovi.org), and the results were graphed using R. Experimental data were modeled using multilevel mixed-effect model analysis (MLM, Satterthwaite methods for degree of freedom) with a random intercept for each participant64. MLM is based on maximum-likelihood estimation, allowing us to predict participant-by-participant variations in model parameters (random effects). Moreover, given the variability due to individual differences in physiological arousal, the MLM allows us to include each participant’s baseline level as a random covariate. In our experimental setup, which involved repeated measurements across multiple days and two distinct groups, utilizing MLM proved valuable approach for analyzing experimental data. In case of significant interaction effects, post-hoc analyses were performed using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons and reporting the difference in estimate value65.

For the self-report craving, we reported data only for the smoker group, given that no craving is expected in non-smokers. However, for thoroughness, the entire analysis, encompassing data from both smokers’ and non-smokers’ groups, is presented in the paper’s supplementary material. The self-reported craving scores were analyzed using a repeated measure design with scenario (neutral vs. smoke) and device (VR vs. 2D) as within factors. Each subject was treated as a random intercept in the model. A linear regression model was used to measure the relationship between self-report craving measurement and FTND score in VR compared to 2-D cue-reactivity exposure.

As regards the electrodermal activity measurements, data were further elaborated using the Matlab-based script Ledalab (version 3.4.8) by adopting a continuous decomposition approach66. The signal was decomposed in data points taken every 20 s of exposure (in both baseline and environment). The software returned the average level of SCL and the number of phasic responses in the selected time window (20 s). The mean value of each experimental phase was used for statistical analysis and analyzed by a repeated measure with the within factors of scenario (levels: neutral vs. smoke) and device (levels: VR vs. 2D), and as between factor participants (levels: smoker vs. non-smoker). Each participant was set as a random intercept, with the baseline level preceding each scenario and individual phasic signal activity included as covariates in the model. The quality of experience (sense of presence and visual realism of experience) was analyzed by a repeated measure with device as within factor (levels: VR vs. 2D) and participants as between factor (levels: smoker vs. non-smoker), using each subject as a random intercept in the model. The correlation analyses between self-reported craving, skin conductance level, and quality of experience were conducted using the Spearman coefficient, with the resulting value reported as rho.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Ekhtiari, H., Nasseri, P., Yavari, F., Mokri, A. & Monterosso, J. Neuroscience of drug craving for addiction medicine: From circuits to therapies. Prog. Brain Res. 223, 115–141 (2016).

Tiffany, S. T. & Wray, J. M. The clinical significance of drug craving. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1248, 1–17 (2012).

Self, D. W. Neural substrates of drug craving and relapse in drug addiction. Ann. Med. 30, 379–389 (1998).

O’Brien, C. Addiction and dependence in DSM-V. Addiction 106, 866–867 (2011).

Sayette, M. A., Martin, C. S., Wertz, J. M., Shiffman, S. & Perrott, M. A. A multi-dimensional analysis of cue-elicited craving in heavy smokers and tobacco chippers. Addiction 96, 1419–1432 (2001).

Wray, J. M., Gass, J. C. & Tiffany, S. T. A systematic review of the relationships between craving and smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 15, 1167–1182 (2013).

Sinha, R. The clinical neurobiology of drug craving. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23, 649–654 (2013).

Courtney, K. E., Schacht, J. P., Hutchison, K., Roche, D. J. O. & Ray, L. A. Neural substrates of cue reactivity: Association with treatment outcomes and relapse. Addict. Biol. 21, 3–22 (2016).

Robinson, T. E. & Berridge, K. C. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: Some current issues. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 363, 3137–3146 (2008).

Robinson, M. J. F., Robinson, T. E. & Berridge, K. C. The current status of the incentive sensitization theory of addiction. In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy and Science of Addiction (eds Pickard, H. & Ahmed, S. H.) 351–361 (Routledge, 2018).

Reynolds, E. K. & Monti, P. M. The cue reactivity paradigm in addiction research. In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Addiction Psychopharmacology (eds Reynolds, E. K. & Monti, P. M.) 381–410 (Wiley, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118384404.ch14.

Drummond, D. C. What does cue-reactivity have to offer clinical research?. Addiction 95, 129–144 (2000).

Carter, B. L. & Tiffany, S. T. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction 94, 327–340 (1999).

Versace, F. et al. Beyond cue reactivity: Non-drug-related motivationally relevant stimuli are necessary to understand reactivity to drug-related cues. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 19, 663–669 (2017).

Yalachkov, Y., Kaiser, J., Görres, A., Seehaus, A. & Naumer, M. J. Sensory modality of smoking cues modulates neural cue reactivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 225, 461–471 (2013).

Tan, H. et al. Drug-related virtual reality cue reactivity is associated with gamma activity in reward and executive control circuit in methamphetamine use disorders. Arch. Med. Res. 50, 509–517 (2019).

Choi, J. S. et al. The effect of repeated virtual nicotine cue exposure therapy on the psychophysiological responses: A preliminary study. Psychiatry Investig. 8, 155–160 (2011).

Guerin, A. A. et al. Assessing methamphetamine-related cue reactivity in people with methamphetamine use disorder relative to controls. Addict. Behav. 123, 107075 (2021).

Gray, K. M., LaRowe, S. D., Watson, N. L. & Carpenter, M. J. Reactivity to in vivo marijuana cues among cannabis-dependent adolescents. Addict. Behav. 36, 140–143 (2011).

Bailey, S. R., Goedeker, K. C. & Tiffany, S. T. The impact of cigarette deprivation and cigarette availability on cue-reactivity in smokers. Addiction 105, 364–372 (2010).

Parsons, T. D., Gaggioli, A. & Riva, G. Virtual reality for research in social neuroscience. Brain Sci. 7, 42 (2017).

Wiederhold, B. K. & Wiederhold, M. D. A review of virtual reality as a psychotherapeutic tool. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1, 45–52 (1998).

Slater, M. Presence and the sixth sense. Pres. Teleoper. Virt. Environ. 11, 435–439 (2002).

Higuera-Trujillo, J. L., López-Tarruella Maldonado, J. & Llinares Millán, C. Psychological and physiological human responses to simulated and real environments: A comparison between Photographs, 360° Panoramas, and Virtual Reality. Appl. Ergon. 65, 398–409 (2017).

Riva, G. et al. Affective interactions using virtual reality: The link between presence and emotions. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 10, 45–56 (2007).

Segawa, T. et al. Virtual reality (VR) in assessment and treatment of addictive disorders: A systematic review. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1409 (2020).

Hone-Blanchet, A., Wensing, T. & Fecteau, S. The use of virtual reality in craving assessment and cue-exposure therapy in substance use disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 844 (2014).

Bordnick, P. S. et al. Assessing reactivity to virtual reality alcohol based cues. Addict. Behav. 33, 743–756 (2008).

Bordnick, P. S., Graap, K. M., Copp, H. L., Brooks, J. & Ferrer, M. Virtual reality cue reactivity assessment in cigarette smokers. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 8, 487–492 (2005).

Bordnick, P. S. et al. Reactivity to cannabis cues in virtual reality environments. J. Psychoact. Drugs 41, 105–112 (2009).

Saladin, M. E., Brady, K. T., Graap, K. & Rothbaum, B. O. A preliminary report on the use of virtual reality technology to elicit craving and cue reactivity in cocaine dependent individuals. Addict. Behav. 31, 1881–1894 (2006).

Traylor, A. C., Parrish, D. E., Copp, H. L. & Bordnick, P. S. Using virtual reality to investigate complex and contextual cue reactivity in nicotine dependent problem drinkers. Addict. Behav. 36, 1068–1075 (2011).

Sandra, Sc., Anusha, R. & Madankumar, P. Application of augmented and virtual reality in cigarette smoking cessation: A systematic review. Cancer Res. Stat. Treat. 4, 684 (2021).

Pericot-Valverde, I., Secades-Villa, R., Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J. & García-Rodríguez, O. Effects of systematic cue exposure through virtual reality on cigarette craving. Nicotine Tob. Res. 16, 1470–1477 (2014).

Keijsers, M., Vega-Corredor, M. C., Msc, D., Tomintz, M. & Hoermann, S. Virtual reality technology use in cigarette craving and smoking interventions (i ‘virtually’ quit): Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e24307 (2021).

Traylor, A. C., Bordnick, P. S. & Carter, B. L. Using virtual reality to assess young adult smokers’ attention to cues. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 12, 373–378 (2009).

Paris, M. M. et al. Cue reactivity in virtual reality: The role of context. Addict. Behav. 36, 696–699 (2011).

Carter, B. L., Bordnick, P., Traylor, A., Day, S. X. & Paris, M. Location and longing: The nicotine craving experience in virtual reality. Drug Alcohol Depend. 95, 73–80 (2008).

Bordnick, P. S., Yoon, J. H., Kaganoff, E. & Carter, B. Virtual reality cue reactivity assessment: a comparison of treatment- vs. nontreatment-seeking smokers. 23, 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731513482377 (2013).

Tamburin, S. et al. Smoking-related cue reactivity in a virtual reality setting: association between craving and EEG measures. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 238, 1363–1371 (2021).

Pericot-Valverde, I., Germeroth, L. J. & Tiffany, S. T. The use of virtual reality in the production of cue-specific craving for cigarettes: A meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 18, 538–546 (2016).

Lee, J. H. et al. Experimental application of virtual reality for nicotine craving through cue exposure. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 6, 275–280 (2003).

Lee, J. H., Lim, Y., Wiederhold, B. K. & Graham, S. J. A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study of cue-induced smoking craving in virtual environments. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 30, 195–204 (2005).

Betts, J. M., Dowd, A. N., Forney, M., Hetelekides, E. & Tiffany, S. T. A meta-analysis of cue reactivity in tobacco cigarette smokers. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 23, 249–258 (2021).

Perkins, K. A. Does smoking cue-induced craving tell us anything important about nicotine dependence?. Addiction 104, 1610–1616 (2009).

Shiffman, S. et al. Does laboratory cue reactivity correlate with real-world craving and smoking responses to cues?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 155, 163–169 (2015).

Riva, G. Virtual reality: An experiential tool for clinical psychology. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 37, 337–345 (2009).

Field, M. & Duka, T. Cue reactivity in smokers: The effects of perceived cigarette availability and gender. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 78, 647–652 (2004).

Choi, J. S. et al. The effect of repeated virtual nicotine cue exposure therapy on the psychophysiological responses: A preliminary study. Psychiatry Investig. 8, 155 (2011).

Xu, J. et al. Gender effects on mood and cigarette craving during early abstinence and resumption of smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 10, 1653–1661 (2008).

Saladin, M. E. et al. Gender differences in craving and cue reactivity to smoking and negative affect/stress cues. Am. J. Addict. 21, 210–220 (2012).

Karelitz, J. L. Differences in magnitude of cue reactivity across durations of smoking history: A meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 22, 1267–1276 (2020).

Bollen, Z., Masson, N., Salvaggio, S., D’Hondt, F. & Maurage, P. Craving is everything: An eye-tracking exploration of attentional bias in binge drinking. J. Psychopharmacol. 34, 636–647 (2020).

Waters, A. J. et al. Attentional bias predicts outcome in smoking cessation. Heal. Psychol. 22, 378–387 (2003).

Schröder, B. & Mühlberger, A. Assessing the attentional bias of smokers in a virtual reality anti-saccade task using eye tracking. Biol. Psychol. 172, 108381 (2022).

Culbertson, C. S., Shulenberger, S., De La Garza, R., Newton, T. F. & Brody, A. L. Virtual reality cue exposure therapy for the treatment of tobacco dependence. J. Cyber Ther. Rehabil. 5, 57–64 (2012).

Goldenhersch, E. et al. Virtual reality smartphone-based intervention for smoking cessation: Pilot randomized controlled trial on initial clinical efficacy and adherence. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e17571 (2020).

Caponnetto, P., Maglia, M., Lombardo, D., Demma, S. & Polosa, R. The role of virtual reality intervention on young adult smokers’ motivation to quit smoking: A feasibility and pilot study. J. Addict. Dis. 37, 217–226 (2018).

Pericot-Valverde, I., Secades-Villa, R. & Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J. A randomized clinical trial of cue exposure treatment through virtual reality for smoking cessation. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 96, 26–32 (2019).

Conklin, C. A. & Tiffany, S. T. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction 97, 155–167 (2002).

Betts, J. M., Dowd, A. N., Forney, M., Hetelekides, E., Tiffany, S. T. A meta-analysis of cue reactivity in tobacco cigarette smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 23(2), 249–258, (2021).

Ferketich, A. K., Fossati, R. & Apolone, G. An evaluation of the Italian version of the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence. Psychol. Rep. 102, 687–694 (2008).

Sayette, M. A., Griffin, K. M. & Sayers, W. M. Counterbalancing in smoking cue research: A critical analysis. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 12, 1068–1079 (2010).

Hox, J. J. & Roberts, J. K. Handbook of advanced multilevel analysis. Handb. Adv. Multilevel Anal. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203848852 (2011).

Monsalves, M. J., Bangdiwala, A. S., Thabane, A. & Bangdiwala, S. I. LEVEL (logical explanations & visualizations of estimates in linear mixed models): Recommendations for reporting multilevel data and analyses. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 20, 1–9 (2020).

Benedek, M. & Kaernbach, C. A continuous measure of phasic electrodermal activity. J. Neurosci. Methods 190, 80–91 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Maristella Zebri and Viola Marinelli for their help in data collection. A. G. is supported by a PRIN (2022-NAZ-0172) grant by MUR Italy.

Funding

The present research is supported by a PRIN Grant n. 2022-NAZ-0172 (Italian Ministry of University and Research – MUR) to Prof. Alberto Gallace.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data collection, Data analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Review & Editing. L.P: VR-software development, Methodology. A.G: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft, Review & Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Girondini, M., Pieri, L. & Gallace, A. Comparing the effectiveness of virtual reality vs 2D display-based cue reactivity paradigms to induce nicotine-craving: a behavioral and psychophysiological study. Sci Rep 15, 5944 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82487-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82487-4