Abstract

Plasmonic nanostructures can help to drive chemical photocatalytic reactions powered by sunlight. These reactions involve excitation of plasmon resonances and subsequent charge transfer to molecular orbitals under study. Here we engineered photoactive plasmonic nanostructures with enhanced photocatalytic performance using non-noble metallic MgB2 high-temperature superconductor which represents a new family of photocatalysts. Ellipsometric study of fabricated MgB2 nanostructures demonstrates that this covalent binary metal with layered graphite-like structure could effectively absorb visible and infrared light by excitation of multi-wavelengths surface plasmon resonances. We show that a MgB2 plasmonic metal-based photocatalyst exhibit fundamentally different behaviour compared to that of a semiconductor photocatalyst and provides several advantages in photovoltaics applications. Excitation of localised surface plasmon resonances in MgB2 nanostructures allows one to overcome the limiting factors of photocatalytic efficiency observed in semiconductors with a wide energy bandgap due to the usage of a broader spectrum range of solar radiation for water splitting catalytic reactions conditioned by enhanced local electromagnetic fields of localised plasmons. Excitation of localised surface plasmon resonances induced by absorption of light in MgB2 nanosheets could help to achieve near full-solar spectrum harvesting in this photocatalytic system. We demonstrate a conversion efficiency of ~ 5% at bias voltage of Vbias = 0.3 V for magnesium diboride working as a catalyst for the case of plasmon-photoinduced seawater splitting. Our work could result in inexpensive and stable photocatalysts that can be produced in large quantities using a mechanical rolling mill procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The hydrogen economy is a sunrise industry considered by many as the ultimate solution to power the future society. As a potential technology for hydrogen production, photocatalytic water splitting is the most promising. Sunlight is a clean and inexhaustible energy gift from nature. The solar radiation reaching the Earth’s surface comprises nearly 100,000 TW power, which is much more than that of the current global power consumption (~ 16.3 TW)1,2,3,4. Practically, the harvesting of solar energy takes place from only a 0.07% Earth’s land surface area of the total amount solar. It was theoretically predicted that converting such amount solar energy into usable form of energy (hydrogen and electricity) with 10% efficiency could cater the global energy demand3,4,5,6. Unfortunately, currently the energy conversion efficiency of photocatalytic water splitting is still too low for large-scale applications (the H2-production activities do not achieve a solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency of over 10%) and a widespread usage of hydrogen as green energy. The present situation in green H2-production demands further developments in nanomaterial engineering to potentially solve the problems of low photoanode effectivity7,8.

Deeper understanding of natural photosynthesis can bring the state-of-the-art modern approaches for designing photocatalytic systems. Usually, for photosynthesis, plants use the water from soil that contains lot of different impurities. On the other hand, in artificial photosynthesis, the direct production of green hydrogen on a large scale using seawater electrolysis is a long-sought dream of researchers9,10. There are only a handful of studies that demonstrated production of H2 from photocatalytic seawater splitting with large current densities at low overpotentials that can meet the industrial requirements, without deactivating the catalysts by the ions of sodium and chlorine11,12. A variety of photocatalysts for seawater splitting has been discussed: nitrides, transition metal hydroxides, sulphides and phosphide, rare earth metal nanocomposites11,12. A usage of seawater splitting for industrial production of H2 is very important task because the oceans represent 96.5% of the total water reserves of the planet that can provide an almost unlimited resource. It is interesting to note that the composition of seawater varies from region to region with the average overall salt concentration of all ions ranges at about 3.5 wt % gives pH ∼ 89,10. At present, the best strategy to produce H2 from seawater is to split it into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity that comes from renewable energy sources, for example, photovoltaic cells. However, it would be much easier and cheaper if sunlight could be used directly to split seawater13,14. This requires new materials and novel mechanisms of photocatalytic seawater splitting. Moreover, to enhance efficiency of photo-water splitting significantly, it is necessary to develop materials that would absorb photons over the wide range of solar spectrum capable of water splitting (SSCWS). To achieve this, one can use metallic nanostructures with different sizes and shapes that would absorb photons over SSCWS due to excitation of the localised surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs) at multi-wavelengths.

Noble metal nanoparticles (NPs) made of Ag, Au, Cu, and Al are receiving increasing attention as photocatalysts, primarily due to the large absorption cross-sections in the visible light provided by their plasmon resonances. Under resonant excitation, the optical cross-sections of plasmonic nanostructures can be ~ 10 times higher than their geometric cross-sections. As a result, large amount of light energy is localised near the surface of plasmonic nanostructures in the form of intense local electromagnetic fields15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Thus, LSPR enhances photocatalysts’ performance through several mechanisms, which include plasmon-induced indirect hot-carrier transfer, direct charge transfer and intramolecular charge transfer, near-field effects and light scattering trapping16,18,19,20,22.

Initially, plasmonic photocatalysts were produced by combining plasmonic metal nanostructures with wide bandgap semiconductors (for example, TiO2) where noble metals NPs functioned as a photosensitizer to enhance the surface reaction on semiconductors20,21. It was shown that a dense array of aligned gold nanorods capped with TiO2 could produce 20 times higher efficiency for water splitting as compared to just TiO2 efficiency23. Linic and et al. were first to report direct molecular oxygen activation and ethylene epoxidation on plasmonic Ag nanoparticles18,24 which triggered an acceleration in the development of plasmonic photocatalysts19,20,21. The idea of plasmonic photo-catalysis is connected to the concentration of solar light near metal NPs by LSPR excitation and then subsequent direct electronic excitations of a material attached to the NPs18,24,25,26,27. The direct electron transfer pathway is expected to have higher transfer efficiency and lower energy losses in comparison to indirect ones21. Note that the direct interaction between plasmonic metal and its surface molecules was also confirmed by Halas’ group16,28. They demonstrated that hot electrons (high energy electrons) induced by LSPR excitations in Au NPs can be direct transferred into a Feshbach resonance of an H2 molecule adsorbed on its surface, causing its dissociation16,28. In review29 was discussed the plasmon excitations in metallic nanostructures based on noble metals as well as non-traditional plasmonic materials resulted in generation hot carriers for photocatalysis and light harvesting processes. Thomann and et al. demonstrated that plasmon-induced photochemistry to streamline chemical reactions can be enhanced by multilayer interference effects which promotes to high concentrate sunlight close to the electrode/liquid interface30. Note that the plasmonic nanostructures with strong optically resonant properties can behave as nanoscale optical antennas for solar light-harvesting and have shown extraordinary promise as light-driven catalysts31.

There are several reasons why metallic catalysts with plasmonic response could be best suited for direct water splitting by sunlight. In contrast to semiconductors, which generally exhibit poor chemical and catalytic activity due to the lack of the electron density at the Fermi level, plasmonic NPs possess significant electron density at the Fermi level, and strongly absorb ultraviolet (UV), visible (VIS) and near-infrared (near-IR) light18. The amount of light absorbed by a plasmonic material (the molar extinction coefficient of metal NPs) is in the range of 108–1010 M− 1 cm− 1, which is approximately 104–106 times higher than most of the light absorbing species known18,32. This essentially means that plasmonic nanostructures can generate large number of high-energy electron–hole (e− - h+) pairs upon irradiation with visible light (≈ 1016 cm− 2). Moreover, some plasmonic nanostructures can effectively utilise photons across the near-IR region wavelengths (750–2000 nm) which concentrates the approximately 50% of the solar energy spectra1,2,3. Unfortunately, mechanisms of the charge injection from excited plasmonic NPs to catalytic molecules are not well understood.

Here we report the room temperature water and seawater splitting on magnesium diboride (MgB2) nanostructures using VIS and near-IR light. We show that inexpensive MgB2 nanostructures provide efficient plasmonic water splitting and could be a viable alternative to noble metal nanoplasmonics. (It is worth noting that noble-like plasmonic metals, such as Cu, Ag, and Au typically exhibit low intrinsic activities with surface-adsorbed molecules due to their fully filled d bands24,32). An introduction of nanostructures based on non-noble metals with high intrinsic direct water splitting activities could present a promising strategy to harvest the solar energy efficiently. In MgB2 nanostructures (unlike in Au, Ag based) the LSPRs are strongly coupled with interband excitations due to a spectral overlap of these processes.

In our previous works we have shown that at the surface properties of MgB2 nanostructures can be actively involve into the process of water splitting in photoelectochemical cells (PECs)33,34. In this study, we demonstrate that interband damping of LSPRs is also an important channel for the formation of e––h+ pairs. These e––h + pairs are separated over two bands (namely, between the π and σ bands) have a longer lifetime and are thereby expected to harvest sun energy more efficiently and contribute to the generation of H2 together with direct electron injection mechanism of hot electrons generated via LSPRs. We also demonstrate that, in sharp contrast to semiconductor photocatalysts, photocatalytic efficiency on plasmonic-like MgB2 nanostructures increases for seawater splitting. More importantly, we suggest and test a new method of fabrication of plasmonic nanostructures with large area on flexible substrates for seawater splitting using mechanical rolling mill procedure which open up avenues to implement design that enable much-improved effectivity and costless of hydrogen production. This method provides stable and dense packed nanostructures.

Experiments and results

Studied materials

In this study, we focussed on MgB2, a binary compound composed of hexagonal boron sheets alternating with Mg cations, as the parent material in the top-down approach for borophene or borophene-related 2D sheets. Metal diborides MB2 typically exhibit a layered honeycomb structure with electron delocalisation within the M − M sublattice and strong covalence in the B − B sublattice, producing stable B − B bonds. It is well known that van der Waals (vdW) interactions between two atomic layers (Mg and B) play an important and crucial role in 2D materials to improve the electrochemical activity6,7,8. It is worth noting that diborides (like MgB2) could hold a promise for photoelectrochemical seawater splitting due to its stability, low-cost, abundance, appropriate bandgap and direct electrons injection into chemical reaction through the decay of plasmons. Figure 1a shows the schematics of the PEC used in our experiments.

Sample fabrication

The layered structure of metal diborides with their graphene-like boron sheets suggests the possibility of exfoliation into thin nanosheets down to a monolayer35. Here we have developed new method of producing metal diborides as quasi-two dimensional (2D) nanosheets using a mechanical rolling mill procedure (Pepetools TM 90 mm Flat Rolling Mill). In this method, diboride powder can be used directly from commercial sources without any further purification. This powder was purchased from Sigma Aldrich with a stated purity of over 99%. Cu foils with thickness of less than 100 μm were used as the substrates. Before pressing, the squared surface of the Cu foil of size 20 × 20 mm was covered with powder totalling a mass of around 30 mg. Another Cu foil sheet was placed on the top of the powder, encasing it between two layers of Cu. To ensure the samples become very thin, they were ran through the rollers multiple times with increasing the force. Due to the fabrication process, the samples were stretched by up to 2 times in surface. This cheap, low-cost and quick method allows producing stable and dense samples that can be used in seawater splitting for a very long time. The produced nanostructures have a distribution of lateral dimensions from tens of nanometers up to several micrometers (0.1–5 μm) and a distribution of thicknesses from as low as few up to tens of nanometers (1–30 nm), which were measured by high resolution optical and scanning electron microscopies (SEM), Fig. 1b, c. The presence of LSPRs nature of fabricated MgB2 nanostructures is confirmed by multiple colours in the optical image, Fig. 1c. One can see that different areas of the sample changes colour from blue to red. In addition, one can see black spots corresponding to total light absorption. The multitude of colours can be explained by a variation of reflectivity characteristics due to excitation of multi-wavelengths LSPRs around the sharp edges of the nanosheets (Fig. 1). The structural properties of the plasmonic MgB2 photo-anode were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique using CuKα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm) in the range of angles 2θ from 20° to 100°. Diffraction peaks were observed in the XRD pattern of the fabricated MgB2 sample. These peaks are associated with the MgB2 crystalline phases36 (Fig. 1d): 2θ≈29.6o (001), 33.5o (100), 42.4o (101), 51.8o (002), 59.9o (110) and were also observed for the MgB2 sputtering target (bulk sample, purchased from American Elements). A few weak peaks at larger diffraction angles 2θ probably originate from the stacking periodicity of MgB2 sheets. Additional peaks for MgB2 nanostructured film on Cu substrate could correspond to the Cu crystalline phases37.

The resistance of the fabricated samples was determined using a digital multimeter. We found that resistance of the nanostructured photo-anodes (30–50 Ω, depending on thickness of flakes) was much larger as compared to that of thick MgB2 (< 1 Ω) measured on a square sample with a side of 10 mm. The initial contact voltage between plasmonic MgB2 photo-anode and Pt photo-cathode embedded in electrolyte in the dark condition was found to be Vinit∼ -0.7 eV in 0.5 M NaCl.

Photocatalytic tests

We have tested the efficiency of a MgB2 nanostructured photoanode in a two-electrode photo-electrochemical cell configuration with a Pt microwire serving as a cathode (Fig. 1a). The white light was provided by a solar simulator AM 1.5G (Newport) which has illumination intensity ∼100 mW cm− 2. The current-voltage (IV) characteristics were recorded using a digital sourcemeter (Keithley, Model 2400) with and without an external potential bias (Vbias) applied across the cell. The most efficient MgB2 photoanodes have generated photocurrents up to 0.95 mA under Vbias =0.7 V in distilled (DI) water (Fig. 2a, size of MgB2 photoanode was ∼1 cm2 and size of a Pt cathode was ~ 0.15 cm2 for all measurements with two electrodes separated by ∼3 mm). The measurements were also carried out in 1 M NaOH aqueous solution at pH ∼13.6 and in 0.5 M LiOH and 0.5 M NaCl (pH ∼7–8). In the presence of electrolytes, the photocurrents were significantly enhanced for all the investigated MgB2-based photoanodes (Fig. 2b-d) as compared to the values plotted in Fig. 2a for the case of DI water. We found that our inexpensive MgB2 nanostructures submerged into a 0.5 M LiOH –DI water solution under a small bias (0.4 V) promote the strong enhancement of light-to-photocurrent conversion.

Magnesium diboride nanostructures as a model system for plasmonics photocatalys. (a) Schematic design of the integrated photoelectrochemical cell using MgB2 nanostructures as the photoanode and Pt cathode in different electrolytes. Right panels (a) layered structure of electrodes and hexagonal structure of MgB2 consisting of honeycomb B (red) layers with close-packed Mg (blue) layers between them. (b) SEM image showing the assembly of MgB2 nanostructured layers. (c) Optical image showing the assembly of MgB2 nanostructured layers which exhibit different colors due to excitation of different localised surface plasmon resonances. (d) X-ray diffraction pattern of the MgB2 nanostructured layer compared with XRD of bulk MgB2.

PEC performance was also measured in a 0.5 M NaCl electrolyte emulating seawater under maximal applied Vbias=0.4 V. The difference between photocurrent in “on” and “off” state reached its highest value of ∼1.2 mA. Note that we cannot apply Vbias larger than 0.45 V in the cases of using electrolytes because of appearance the periodical jumps of current to very high values > 10 mA which is analogical to ones described in works38,39. Observed fluctuations and a slight drop of the measured currents on longer timescales under illumination are mainly caused by the bubble formation on the surface of the MgB2 photoanode (which generated O2) and the Pt (which generated H2). The bubbles can be seen by naked eyes in a dark room under solar illumination (Figure S1, Supplementary Information (SI)). Optical images taken during the formation and growth of bubbles on the water splitting photoanode and cathode were used for the measurement of the gas-evolving reaction rate. The conversion efficiency has been calculated using bubble microscopy40. These measurements confirmed 0.95% Faraday efficiency (each two electrons generated ∼0.95 molecules H233). Note that the decreasing of currents on longer timescales can be also caused by heating of solution during solar illumination. The dependences of current versus time are restored if change the electrolyte on the fresh (in this case the bubbles are removed and solution is at room temperature) and the measurements are repeated. Therefore, we found that MgB2 nanostructures can effectively absorb solar energy facilitating the reaction of water/seawater splitting and deliver the electrons and holes required for generation of hydrogen and oxygen gases. In order to find the optimal value of bias voltage needed to be applied, we used cycling voltammetry (CV). To this end, we cycle the bias voltage applied to the investigated MgB2 anodes in the seawater (0.5 M NaCl electrolyte) linearly from the lowest potential − 0.7 V to the highest + 0.7 V and then in reverse, see Figure S2. In the case of a 2-electrode system (anode and cathode), the voltage in the x-axes corresponds to the bias applied to the whole device. We have chosen the bias voltage which corresponded to the point where the peak current was observed which provided the most effective value for the maximal efficiency of the photocatalytic process studied.

The enhancement of light-to-photocurrent conversion can be described by incident photon to current conversion efficiency (IPCE) calculated as1,6:

where JSC is short-circuit photocurrent density, Vbias is the applied potential between photoelectrode and counter electrode, Plight is the total irradiation input, and the redox potential of interest is equal to 1.23 V for water oxidation. The integrated efficiency IPCE together with monochromatic IPCE(λ) were calculated from measuring the photocurrent JSC and are presented in Table S1. It was found that the maximal efficiency could be achieved by selection of optimal ions and their concentrations in the electrolyte that provide the maximal ion mobility. The evaluated efficiencies represent the normalised on the square A (cm2) of the geometrical area of photo-anode or cathode. The highest efficiency of 1.3% (normalised to the anode area) or 6.5% (normalised to the cathode area) for MgB2 nanostructure was obtained in the case of PEC filled with solution of 0.5 M of LiOH in the DI water. In the case of seawater splitting the highest efficiency was ∼1.0% (normalised to the anode area) or ∼5% (normalised to the cathode area) and has been achieved under Vbias=0.3 V.

To check that the water-splitting reaction is indeed excited by the VIS and near-IR parts of solar spectrum, we have measured the photo-generated current under monochromatic sources of various wavelengths. Figure 2e, f show examples of photocurrents generated by blue (λ ≈ 440 nm), green (λ ≈ 540 nm), yellow (λ ≈ 600 nm) and red (λ ≈ 720 nm) monochromatic light approximately the same density power (∼10 mW/cm2). Wavelength selection was done by applying a set of band pass filter (FWHM Δλ≈ 20 nm, Thorlabs) using the solar simulator as the light source. The experiments were carried out in 0.5 M LiOH and 0.5 M NaCl aqueous solution at pH ∼7. These measurements give evidence that there is significant spectral increase of the effectiveness of photocurrent generation toward the near-IR part of the spectrum. We observe a maximum approximately single-wavelength power conversion efficiency of ∼2.7% under 10 mW cm− 2 of 720 nm monochromatic illumination (Table S1). The evaluated IPCE(λ) for 720 nm is approximately 2.25 times as large than that of the for 440 nm (Fig. 2e, f). To explore the feasibility of water splitting by utilizing external electrons from excitation of LSPR in the MgB2 nanostructures at the red and near IR wavelengths it was additionally tested the monochromatic photocatalysis for Vbias=0.2 V (see supplementary information, Figure S3). Obtained data confirm the tendency of the IPCE action spectra presented in the Fig. 2d.

Solar water splitting. Photocurrent as a function of time and external voltage, Vbias, for the integrated water splitting device under illumination a solar light simulator: (a) nanostructured MgB2 photoanode and the Pt cathode submerged in deionised water; (b) nanostructured MgB2 photoanode and the Pt cathode submerged in 0.5 M LiOH electrolyte; (c) nanostructured MgB2 photoanode and the Pt cathode submerged in 1 M NaOH electrolyte; (d) nanostructured MgB2 photoanode and the Pt cathode submerged in 0.5 M NaCl electrolyte – sea water; (e, f) photocurrents generated by blue (λ ≈ 440 nm), green (λ ≈ 540 nm), yellow-red (λ ≈ 600 nm) and red (λ ≈ 720 nm) monochromatic light in 0.5 M LiOH and 0.5 M NaCl electrolytes, respectively.

Examination of short-circuit current Isc yielded nearly linear dependence on the increasing of the wavelength from blue to the near-IR region, as expected in an ideal photovoltaic device. Note that for both electrolytes (0.5 M of LiOH and NaCl) the measured monochromatic IPCE(λ) maxima match with the simulated absorbed fraction within the MgB2 nanostructures. The numerical absorbed fraction reaches about 90% for the 150–200 nm MgB2 particles and about 70% for the 250 nm particles in the spectral range 500–1000 nm for the same layer thickness of 100 nm (Fig. S6).

FTIR spectroscopy. To analyse the contamination of the appeared bubbles on the surface of photoanode (MgB2) we employed the Fourier Transform Infra-Red (FTIR) spectroscopy (a Bruker Vertex 80 system with a Hyperion 3000 microscope)41. The measurement of the mid-IR reflection spectra was done at normal incidence in the frequency range from 550 to 4000 cm− 1 by performing 256 scans with a resolution of 4 cm− 1 using cryogenic MCT detector cooled with liquid nitrogen. We carried out FTIR measurements on MgB2 nanostructure surface in the areas without and with bubbles in the 0.5 M NaCl electrolyte. The inset of Fig. 3a shows the optical image of forming bubble on the MgB2 nanosheets taken by the standard 15x IR (NA=0.4) Schwarzschild objective before/after measuring the FTIR spectra. The spherical surface of bubble performs the additional focusing of incident light and works as lens. As displayed Fig. 3a, new reflection peaks appear for areas contained bubbles. The broad band observed in the range 3000–3500 cm− 1 corresponds to the B–OH stretching mode or water bending and indicates possible hydroxyl functionalisation. The peak at ∼628 cm− 1 for MgB2 nanostructures on bubbles correspond to a B-OH in-plane bending or the B-B in-plane stretching mode and vibration mode at ∼1420 cm− 1 associated with B-O stretch. The band at ∼1118 cm− 1 can also be attributed to the presence of B–OH functional groups as the B–OH in-plane bending is usually observed to be around 1000–1300 cm− 1. The strong band observed at ∼1624 cm− 1 can be ascribed to hydrogen motions in B–H–B bridge or water bending. The bubbles of MgB2 nanosheets sample also exhibit a moderate band at ∼2445 cm− 1, likely due to B–H stretching36,42.

Natural seawater is a complex neutral electrolyte, containing main ions such as Cl−and Na+. The major issues associated with direct seawater photoelectrolysis are: (1) the undesired anodic chloride oxidation reactions - the chlorine evolution (2Cl− → Cl2 + 2e−) and the formation of hypochlorite (Cl− + 2OH− → ClO− + H2O + 2e−), competing with the oxygen evolution reaction (OER); (2) the high energy cost caused by the reaction kinetics for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and OER in such medium. To examine the selectivity of both oxygen and chloride evolution we employ FTIR for analysis of MgB2 photo-anode surface before and after conducting photocurrent measurements (see, Fig. 3b). The fresh MgB2 sample displays bands corresponding to OH stretching at 3400–3700 cm− 1 and water bending at ∼1650 cm− 1, which are indicative of adsorbed moisture. After conducting photocurrent measurements under bias of Vbias=0.3 V in water/seawater environments the FTIR spectra of MgB2 sample have similar features. The surface of a photoanode exhibits an absorption band at ∼2485 cm− 1, likely due to B–H stretching and a band at ∼1585 cm− 1 which can be ascribed to hydrogen motions in B–H–B bridge. Strong absorption in the range of ∼1100–1250 cm− 1 is characteristic of B–O stretch and hence the band at 1133 cm− 1 can be assigned to the presence of oxy-functional groups on boron lattice. FTIR data give evidence that the majority of water molecules at the interface are H- or HO-bounded to the surface.

In situ FTIR spectra of an interaction of a photo-anode MgB2 with 0.5 M NaCl electrolyte are recorded under applied Vbias=0¸0.4 V, see Fig. 3c. They demonstrate an increase of intensity of reflection spectra in the regions of 1000–1500 cm− 1 and 2500–3000 cm− 1 induced by the applied bias voltage, Vbias. The main bands at ∼1665 cm− 1 and ∼3577 cm− 1 show different bias dependence, see Fig. 3c. The absolute intensity of reflection dip at ∼1665 cm− 1 decrease with increasing Vbias while the feature at ∼3577 cm− 1 exhibit a much smaller bias dependence. According to Huber43, vibration modes associated with Mg–Cl should be expected at < 700 cm− 1. They were not observed in the reflection spectra, see Fig. 3b, c. Thus, FTIR study confirms the absence of chlorine production on the surface of MgB2 films. It may be possible that a small amount of free chlorine (dissolved Cl2 or HClO) could be present but not recorded by FTIR. It is clear that this value is negligible compared to the formed amounts of H2 and O2.

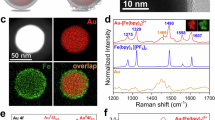

FTIR and Raman spectroscopic results. (a) The FTIR spectra in the middle IR region taken from MgB2 nanostructure surface in the areas without and with bubbles after water splitting of 0.5 M NaCl electrolyte. Insets (a): Optical images of forming bubbles on the MgB2 nanosheets taken by the standard 15x IR (NA=0.4) Schwarzschild objective before/after measuring the FTIR spectra. Bubble works as an additional focusing lens. (b) FTIR measurements on plasmonic MgB2 photo-anode surface before and after water/seawater splitting experiments performed under Vbias=0.3 V. (c) In situ FTIR spectra of interaction plasmonic MgB2 photo-anode with 0.5 M NaCl electrolyte under application of different bias voltage Vbias=0¸0.4 V. (d, e) Surface enhanced Raman signals from R6G dye molecules placed on top of MgB2 nanosheet assemblies due to LSPRs of metallic MgB2 nanostructures providing highly enhanced electromagnetic fields: (d) excitation with λ = 514.5 nm and (e) excitation with λ = 632.8 nm.

Chemical surface analysis of the MgB2 photo-anodes was carried out using energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) for two samples before (fresh sample) and after (working sample) solar-driven seawater splitting. The SEM and EDX images of the analysed samples and corresponding spectra of the compositions elements are presented in Fig. S4. They show the presence of Mg and B components in the both samples. They also demonstrate the presence of small amount of C, N and O embedded into the MgB2 lattice. We further observed an evidence of a small amount of Na on the surface of plasmonic MgB2 photoanode after water splitting. An amount of detected Cl was very small indicating the absence of Cl corrosion. The increased amounts of the oxygen on the surface of MgB2 photoanodes after conducting photocurrent measurements (right panel in Fig. S4) is, perhaps, due to forming of O2 bubbles on MgB2 electrode during water splitting. Therefore, results of the EDX measurements provide experimental evidence that supports our optical investigation by FTIR. We are planning to perform gas analysis under seawater splitting in near future.

Raman spectroscopy

Metallic NPs can contribute to the enhancement of Raman signal through their localized electromagnetic hotspots provided by LSPRs. To test electromagnetic field enhancement due to LSPRs in the fabricated milled MgB2 nanostructures, we spin-coated the samples with a 10− 6 M of R6G solvent in PMMA 950, 3% anisole and measured Raman spectra of the final system. The Raman measurements were performed using a Witec confocal scanning Raman microscope under a 514.5 and 632.8 nm laser illuminations and a 1800 lines/mm grating, and a ×100 objective (N.A. = 0.90). The laser spot size was approximately ∼3 μm while the laser incident power did not exceed ∼0.2–0.5 mW (to avoid a damage or oxidation of MgB2 nanosheets and R6G molecules). The Raman spectra of R6G on pure substrate and substrate-MgB2 nanosheets are shown in Fig. 3d, e. The three characteristic peaks at 1437, 1502, and 1613 cm− 1 are compared in Fig. 3d for the pure 10− 6 M R6G, and combination of MgB2 nanostructures and 10− 6 M R6G dye layer (about 100 nm of thickness). We revealed that the resonant Raman signal of R6G dye is enhanced by 10–15 times in magnitude by near-fields of plasmonic MgB2 nanostructures. Enhancement factors of Raman 1502 and 1613 cm− 1 peaks are different for different excitation wavelengths (514.5–632.8 nm). The strongest enhancement in the Raman spectrum was observed under a laser excitation wavelength of 632.8 nm (Fig. 3e), indicating the strong LSPR effect of the laser light scattering on the MgB2 nanostructures. Thus, over 15 times enhancement of Raman signal was observed for R6G on nanostructured MgB2 substrates. We assume that LSPRs of hybrid MgB2 nanosheets concentrate the electromagnetic fields near the surface and edges nanostructures creating plasmonic hotspots on the sharp edges around the perimeter of nanoflakes and in small gaps between neighbouring flakes. These plasmonic hotspots can amplify both the excitation and emission radiation and thus enhance the weak Raman signals from R6G molecules21,44.

Ellipsometric measurement of the complex dielectric function

To determine the complex dielectric function and optical absorption of fabricated MgB2 nanostructures, the ellipsometry method was employed using a variable angle focussed-beam spectroscopic ellipsometer Woollam M 2000 F in the wavelength range of 240–1690 nm. The spot size on the sample was approximately 50 μm × 70 μm at ~ 70–80° angles of incidence. The ellipsometry measurement essentially monitors changes in the polarized reflection. It yields two spectral parameters (Ψ and Δ) related with the amplitude (tanΨ) and phase Δ of a complex reflectance ratio ρ that provides the ratio of the reflection coefficient for p-polarised, rp, and s-polarised, rs, light as ρ = rp/rs = (tanΨ)exp(iΔ)41,45,46,47. The ellipsometric measurements were done at an angle of incidence of light close to θi = 73o corresponding to the pseudo-Brewster angle of the sample in VIS. A pseudo-Brewster angle for metal provides a sharp jump in Δ -ellipsometric phase and ellipsometric measurements are the most sensitive and precise near this incident angle45. To model the measured ellipsometric data, we applied an isotropic model for thick MgB2 layer with the aim to extract values of the complex dielectric function ε*= ε1 + iε2 or the complex refractive index n*=n + ik. The fitting of the ellipsometry data were performed using Woollam WVASE32 software in which the complex dielectric function can be extracted using the Fresnel theory. The corresponding real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function ε*= ε1 + iε2 and refractive index n*=n + ik are displayed in Fig. 4. Previous analysis of the absorptive part of the dielectric function ε2 show that main features are associated with the bulk plasmonic peaks in the blue range (~ 400 nm) and broad absorptive region stretched from 500 to 1500 nm. The resonance peaks and dips in the optical spectra in Fig. 4 are the results of specific morphology, i.e. shape, size, and configuration of MgB2 nanostructures. Obtained dependences of ε1 and ε2 versus wavelength for fabricated MgB2 nanostructures are very different from that of bulk MgB2 which can be found in the works of Kuzmenko (Fig. 4a-d)48,49. It was shown that the plasma edge for bulk MgB2 is smeared due to the strong interband transition in the region 400–500 nm (flat shoulders in ε1 and ε2 (Fig. 4b)). As a result, the reflectivity spectrum of bulk MgB2 in the visible range is relatively flat with a maximum at ∼ 440 nm which demonstrates only blue-silver colour in contrast to multiple colours image of MgB2 nanostructures (Fig. 1). It means that different surface electronic states in the bulk and nanostructured MgB2 layer lead to different surface collective electronic excitations. We can conclude that the electronic structure of nanoscale MgB2 is highly sensitive to LSPRs and uncompensated surface chemical bonds50. The experimental results displayed in Fig. 4 also demonstrate that the plasmonic response of MgB2 nanostructures can be tuned by adequate choice of the size throughout the visible wavelength range and further into the near-infrared range.

Optical properties of MgB2 nanostructured films. (a, b) The real and imaginary parts of the refractive index (a) and the dielectric function (b) for the plasmonic MgB2 bulk metal based on approach of44 (Table S2). (c) Comparison of the complex refractive index evaluated from ellipsometric measurement and theoretically simulated dependences based on polarizability of the discs-like nanostructures with strong LSPRs. (d) The real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function for the plasmonic MgB2 nanostructured films: experimental and theoretical dependences.

Plasmonic mechanism of water splitting on MgB2 nanostructures

The first direct evidence of excitation of LSPRs in fabricated MgB2 nanostructures is multiple colours on the optical microscopy images, Fig. 1c. (The colour of amorphous or crystalline MgB2 is normally black.) The second evidence of LSPRs excitation and hence plasmonic mechanism in photocatalytic seawater splitting based on the MgB2 nanostructures is the enhancement of Raman light scattering shown in Fig. 3. The third confirmation of the presence of LSPRs in the studied samples lies in the spectral dependence of the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function for MgB2 nanostructures which can be modelled as a sum of excited multi-wavelength LSPRs in the spectral range of 400–1000 nm. Indeed, the dielectric permittivity of bulk MgB2 ε*b= ε1b + iε2b can be described as contributions from the intraband electron transition (the Drude term for electronic response of the free electrons in the conduction band) and interband transitions between two σ-bands and from σ band to the π band close to the M-point of Brillouin zone where a van Hove singularity strongly enhances the density of states48,49. The interband electron transitions contribute to the dielectric function as sum of the Lorentz oscillators. The bulk ε*b= ε1b + iε2b for MgB2 can be described using the Drude–Lorentz parameters taken from48. The real part of the dielectric function ε1b for bulk MgB2 becomes negative across a wide range of wavelengths as shown in Fig. 4b. It means that the condition for LSPR excitation (ε1b≈-2, and a small value of ε2b) can be established for MgB2 metal in air at visible- near IR wavelengths. Thus the combination of ε1b ≈ − 2 and low ε2b stipulate that nanostructured MgB2 could exhibit LSPRs in VIS and near-IR.

To reproduce the complex dielectric function of the fabricated MgB2 nanocomposites (Fig. 4) we used the Maxwell-Garnet effective medium approximation (EMA)46,51. According to the EMA in the case when incident light wavelength is much larger than the size of the nanostructure, the MgB2 nanodiscs-like can be approximated by dipoles with corresponding polarizabilities, αj. The MgB2 nanocomposites were considered as discs with a thickness of 25 nm and different diameters in the range from 25 to 500 nm estimated from SEM data (Fig. 1). The volume fraction f of the MgB2 nanodiscs was found from the best fit as f = 0.67 (f ≈2/3 of the dimension - volume fraction of MgB2 nanodiscs in the air, see in detail SI). Figure 4c, d and supplementary Fig. S5 show the real and imaginary parts of the modelled dielectric function and optical constants of MgB2 nanodiscs as a function of wavelength (see SI). Displayed dependence of the dielectric permittivity was obtained as a sum of contribution from assemblies polarised nanodisc-like dipoles with different weighting. As expected from the broad size nanodiscs distribution, we observe a substantial spectral spread in LSPRs leading to an essential broadening of the experimentally measured absorption. The calculated data (Fig. 4c, d) give a reasonable quantitative description for the optical properties of the MgB2 nanostructures except in the regions below λ < 400 nm and above λ > 800 nm where plasmonic resonances of higher orders and scattering on roughness surface should be taken into account. In Figures S6a-c, we show the calculated total absorbed (Ap), reflected (Rp) and transmitted (Tp) fractions of normally incident light in air for MgB2 nanodiscs (the calculations were done using approach of our previous works46,52,53 (see SI)). Our modelling predicts a sufficient solar light absorption of a nanostructured MgB2 photoanode at wavelengths λ > 400 nm (Fig. S6) due to a broad size distribution of nanosheets leading to excitation of multi-wavelengths LSPR. Note that most of nanosheets demonstrate an anisotropic shape (SEM images, Fig. 1) which is the reason for plasmon resonances being shifted to the red and near-IR wavelength range.

A plasmonic mechanism of photocatalytic DI and seawater splitting based on the MgB2 nanostructures was also confirmed by occurrence of SERS-like signal (Fig. 3d, e) which can be attributed to the electromagnetic origin. In the case of classical plasmonic NPs such as Ag or Au, the process of Raman light scattering dominates due to the plasmon relaxation for relatively large NPs (over ~ 100 nm)21, while for smaller (less than ~ 30 nm) and larger (d > 300 nm) NPs the e–h pair formation is the dominant process54. The excitation of the LSPRs in MgB2 nanostructures enhances the weak Raman signals (Fig. 3d, e) in a SERS-like process and significantly enhance the water splitting in photo-electrochemical process (Fig. 2). We also found that plasmonic MgB2 photo-anodes display smaller values of the real and imaginary parts of the refractive index, n + ik, in comparison to those of thick MgB2 (Fig. 4). It is worth noting that n is ranged between 1.5 and 1.6 while is 0.5 < k < 0.7 (500 < λ < 700 nm). Obtained values of the n and k come close to the perfect absorption conditions in water because the refractive index, n, matches condition n ≈ Nwt≈1.33 together with a small k lead to a small reflection from the interface water-photo-anodes according to the Fresnel theory55,56 given by R={(n-Nwt)2 + k2}/{(n + Nwt)2 + k2}≈ k2/(n + Nwt)2. Moreover, reasonably small imaginary part of the refractive index k can affect the strong light absorption in the photo-anode provided 2πkd/λ⪢1, where d≈50–100 nm is thickness of a photo-anode.

The experimental studies and theoretical modelling demonstrate that Mg- and B- terminated states in the multi-layered MgB2 nanosheets are responsible for the excitation of LSPRs and tunable band gaps in the surface states33,34,50. Our modelling of Ap, Rp and Tp (Fig. S6) showed that assemblies of MgB2 nanosheets exhibit evidence of a direct plasmonic absorption, which is distinctly different from previously reported metallic-like interband transitions48,49. As nanostructures become more isotropic, i.e., the aspect ratio of diameter to thickness tends toward unity, the LSPRs of the particles become blue-shifted (peak around of 400 nm in the dielectric function, Fig. 4). Note that for a random distribution of nanodiscs with diameters ranging from 100 to 250 nm and a thickness of 25 nm, the plasmonic peaks cover a region from around 600 to 900 nm. The strongest plasmon peak is located at ~ 700 nm since nanodiscs with 200 nm diameter have the highest occurrence in our studied MgB2 samples. In addition, smaller particles cause significantly smaller absorption because of their decreased volume. As a result, an assembly of MgB2 nanosheets with plasmonic absorption could be better suited to collect VIS and near-IR light for water splitting than wide band gap semiconductors1,3,13 and, therefore, can significantly improve the solar-to-energy efficiency of photocatalytic H2 generation.

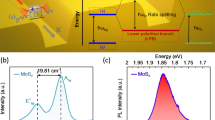

A schematic model of a plasmonic photocatalytic mechanism of water splitting with non-noble metals is presented in Fig. 5. As was shown in our previous works33,34, electron-hole pairs in MgB2 nanostructures are created by interband transitions between π and σ bands due to the light absorption. This transition originated from a van-Hove singularity in the electronic structure of MgB2 and is separated by the energy of ∼ 2.0-2.6 eV33,57. Generation of the electron-holes pairs at the metal surface, in analogy with excitons in semiconductors, can occur due to the significant decreasing and slowness of the Debye screening as results of the electron-hole interactions through the surrounding dielectric54. Such existence of the electron-holes pairs at the surface is favourable for MgB2 because the alternating layers of Mg and B are charged due to ionic/covalent interaction between them50. Moreover, metallic Mg layers give electrons to semiconducting B layers and become positively charged while B layers accept electrons and become negatively charged58. Electrical stability of the MgB2 is provided due to the compensation of the Mg ionic charges by the negative charges on the subsurface B nanosheets. Note that angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy confirmed the appearance an additional band assigned to a surface state of the terminated Mg- and B-surfaces59. From point of view of the electronic structure, we can consider the MgB2 nanostructured surfaces as an n-type doping of the clean B-terminated surface because the Mg atoms donate electrons interstitially. In the suggested model, we prescribe the semiconductor-like electronic behaviours to the surface of big nanosheets d > 300 nm. In order to facilitate the water splitting with semiconductor catalysts, the bottom level of the semiconductor conduction band should be more negative than the redox potential of H+/H2 (VH+/H2= -4.44 eV vs. vacuum level, or 0 eV relative to the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE)) while the top level of the valence band should be more positive than the redox potential of O2/H2O (VO2/H2O=- 5.67 eV vs. vacuum level, or 1.23 eV relative to SHE)4,6. For MgB2, it was found33,50 that the B-terminated surface gives a work function of ΦB ≈ 5.95 eV (∼1.45 eV vs. SHE), with ΦH ≈ 4.5 eV), while the Mg-terminated surface gives ΦMg ≈ 4.25 eV (− 0.25 eV vs. SHE). Energy diagram Fig. 5 shows that the difference between energies, ΦB-ΦMg, exceed the Gibbs free of water splitting meaning this energy is enough to split one of water molecule into H2 and O24,6. MgB2 nanostructures absorb solar photons and produce electron-hole pairs leading to redistribution of surface electrons and corresponding potentials. Due to a larger number of excited electrons, the top π-band becomes more negative than the redox potential of H+/H2 (0 V vs. SHE) while, due to collection of holes, the bottom σ-band of surface electrons tends to obtain a positive potential that is larger than the redox potential of O2/H2O (1.23 V vs. SHE) (see Fig. 5). It means that energy separation between the π- and σ-bands would be enough for photocatalytic water splitting reaction31,34,60.

Schematic model (Fig. 5) also shows plasmon-induced photocatalytic reactions under LSPR excitations and a LSPR-mediated electron transfer process. Furthermore, the broad distribution of the resonance wavelengths provided by different sizes and shapes of MgB2 nanostructures suggests that the entire solar spectrum could be exploited in plasmonic-metal photocatalytic reactions. We can assume that the fabricated plasmonic nanostructures behave as assemblies of electromagnetic dipoles strongly interacting with solar radiation. When a plasmonic nanostructure interacts with light of the same frequency as its own LSPR, the resonance is established between the electronic plasma and the incoming photons. As a result, the electric field in the surroundings of the nanostructure is significantly enhanced. This can influence electron transitions from the σ - and π-bands in the neighbouring nanostructures and provoke electron–hole pair formation in the phenomenon known as plasmon resonance energy transfer (PRET)15,20,21. The plasmon resonance frequency of our photo-anode nanostructured material lies at around 600–800 nm as evident the monochromatic photocatalytic reactions (Fig. 2e, f); thus, we can expect a maximum energy of ∼1.5-2 eV for hot-electrons generated from the LSPRs. Such energetic electrons from plasmonic MgB2 nanostructures can be injected into the π-band of larger MgB2 nanosheets (Fig. 5). From a quantum perspective, the LSPR excited state can be described as a coherent superposition of low-energy electrons and holes near the Fermi level (EF)16,17,18,61.

Schematic of plasmon-enhanced water splitting on MgB2 nanostructures catalyst. (a) Schematic of Fermi-Dirac type distribution of high energy electrons originated from LSPs of small MgB2 nanostructures d < 300 nm, energy diagram of localisation of the Fermi level (EF) and LSPRs states for plasmonic MgB2 nanosheets and proposed mechanism of hot-electron induced dissociation of H2O on MgB2 surface (left part of panel). Overview of the energy level positions of surface electrons on the MgB2 nanosheets of large sizes d > 300 nm with respect to the redox potential of H+/H2 (0 V vs. SHE). The top potential of surface electrons (π-like B) is more negative than the redox potential of H+/H2 (0 V vs. SHE) while the bottom potential of surface electrons (σ-like B) is more positive than the redox potential of O2/H2O (1.23 V vs. SHE) (right part of panel). Electron-transfer processes locally redistributed electron densities across plasmon/semiconductor-like (indirect transfer (I)) and plasmon/absorbate (H2O or electrolyte molecules) interfaces (direct transfer (II)).

Overall, one could assign plasmon-induced water splitting with MgB2 nanostructures to a direct plasmon-induced charge transfer conditioned by a significant energy and spatial overlap between the oscillating electron density within MgB2 nanosheets and electron-accepting orbitals of H2O. Recently, Meng and co-workers theoretically described mechanism of plasmon-induced water splitting at atomic scale and identified the unexpected mode-selectivity in water splitting rate on small metal NPs62. They revealed that direct plasmon-induced charge transfer occurs when high electron energy overlap with water’s antibonding state. Being in an exited “hot” state, electrons have enough energy to overcome the energy barrier required for driving the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) with a redox potential that lies at an excitation energy of about 1 eV above the Fermi energy of the MgB2 nanosheets. Such electrons with energies greater than 1 eV (in addition to over-potential) can transfer directly to the unoccupied states of the H2O and thus result in the initiation of the photocatalytic HER. Cycling voltammetry scans (Fig. S2) show that the peak response at ∼0.25 V provides еру total energy of electrons as ∼1.25 eV which exceeds the required energy for direct driving of HER. Note that the density of electronic states at the Fermi level is significantly larger for low dimension MgB2 nanosheets than that in the bulk MgB258 leading to an enhancement of photocatalytic HER due to increased numbers of energetic electrons. Therefore, we can assume that photo-catalytic activities of the studied MgB2 nanostructures come from both semiconducting-like MgB2 surface states and surface LSPRs arising near terminated Mg- and B- edges (Fig. 5).

In conclusion, a new method of fabrication of larger area flexible plasmonic nanostructure photocatalysts for water and seawater splitting has been suggested. The method is based on a mechanical rolling mill procedure and can be easily implemented by industries. Our study demonstrates effective plasmon-induced seawater splitting with the help of the fabricated MgB2 nanostructures. These plasmonic nanostructures consist only of metallic MgB2 nanosheets and promise much better efficiency than that of semiconductor photocatalysts often restricted by their large bandgap. The complex dielectric function of the MgB2 nanostructures has been determined and confirmed the presence of multi-wavelength LSPRs in the system. Experimental data on monochromatic water splitting and Raman scattering enhancement strongly suggest that the efficiency of photocatalysts depends not only on optical absorption of MgB2 nanostructures, but also on their localised plasmons. An excitation of LSPRs in MgB2 water splitting nanostructures can offer a series of unique properties and functionalities, including spectral tuneability that can be achieved by varying the nanostructure size and shape, size selectivity, electric field enhancement enabling a boost of photocatalytic hydrogen generation from seawater. We showed that non-noble metal plasmonic nanostructures could allow one to overcome limiting factors of photocatalytic efficiency existing for broad bandgap semiconductors by using the whole range of the solar spectrum that can drive the photocatalytic reactions. We hope that this study will provide a unique approach for guiding further developments of plasmonic photocatalysts.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Change history

19 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90715-8

References

Walter, M. G. et al. Solar Water Splitting cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6446–6473. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr1002326 (2010).

Jacobson, M. Z. & Delucchi, M. A. Providing all global energy with wind, water, and solar power, part I: technologies, energy resources, quantities and areas of infrastructure, and materials. Energy Policy. 39, 1154–1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2010.11.040 (2011).

Kudo, A. & Miseki, Y. Heterogeneous photocatalyst materials for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1039/B800489G (2009).

Jain, I. P. Hydrogen the fuel for 21st century. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 34, 7368–7378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.05.093 (2009).

Marchenko, O. V. & Solomin, S. V. The future energy: Hydrogen versus electricity. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 40, 3801–3805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.01.132 (2015).

Chen, X., Shen, S., Guo, L. & Mao, S. S. Semiconductor-based Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Chem. Rev. 110, 6503–6570. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr1001645 (2010).

Green, M. A. & Bremner, S. P. Energy conversion approaches and materials for high-efficiency photovoltaics. Nat. Mater. 16, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4676 (2017).

Lee, M. M., Teuscher, J., Miyasaka, T., Murakami, T. N. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on Meso-Superstructured Organometal Halide Perovskites. Science 338, 643–647. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1228604 (2012).

Dresp, S., Dionigi, F., Klingenhof, M. & Strasser, P. Direct electrolytic splitting of seawater: Opportunities and challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 933–942. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.9b00220 (2019).

Tong, W. et al. Electrolysis of low-grade and saline surface water. Nat. Energy. 5, 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0550-8 (2020).

Kuang, Y. et al. Solar-driven, highly sustained splitting of seawater into hydrogen and oxygen fuels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 116, 6624–6629. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900556116 (2019).

Gao, Y. et al. Rhodium nanocrystals on porous graphdiyne for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution from saline water. Nat. Commun. 13, 5227. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32937-2 (2022).

Fujishima, A. & Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238, 37–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/238037a0 (1972).

Bolton, J. R., Strickler, S. J. & Connolly, J. S. Limiting and realizable efficiencies of solar photolysis of water. Nature 316, 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1038/316495a0 (1985).

Li, Z. & Kurouski, D. Plasmon-Driven Chemistry on Mono- and bimetallic nanostructures. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 2477–2487. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00093 (2021).

Mukherjee, S. et al. Hot electrons do the impossible: Plasmon-Induced Dissociation of H2 on au. Nano Lett. 13, 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl303940z (2013).

Kim, Y., Smith, J. G. & Jain, P. K. Harvesting multiple electron–hole pairs generated through plasmonic excitation of au nanoparticles. Nat. Chem. 10, 763–769. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-018-0054-3 (2018).

Christopher, P., Xin, H. & Linic, S. Visible-light-enhanced catalytic oxidation reactions on plasmonic silver nanostructures. Nat. Chem. 3, 467–472. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1032 (2011).

Yan, L., Ding, Z., Song, P., Wang, F. & Meng, S. Plasmon-induced dynamics of H2 splitting on a silver atomic chain. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 083102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4929611 (2015).

Zhang, X., Chen, Y. L., Liu, R. S. & Tsai, D. P. Plasmonic photocatalysis. Rep. Prog. Phys. 76, 046401. https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/76/4/046401 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Surface-Plasmon-Driven Hot Electron Photochemistry. Chem. Rev. 118, 2927–2954. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00430 (2018).

Kale, M. J., Avanesian, T., Xin, H., Yan, J. & Christopher, P. Controlling Catalytic selectivity on metal nanoparticles by direct photoexcitation of adsorbate–metal bonds. Nano Lett. 14, 5405–5412. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl502571b (2014).

Lee, J., Mubeen, S., Ji, X., Stucky, G. D. & Moskovits, M. Plasmonic photoanodes for solar water splitting with visible light. Nano Lett. 12, 5014–5019. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl302796f (2012).

Linic, S., Aslam, U., Boerigter, C. & Morabito, M. Photochemical transformations on plasmonic metal nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 14, 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4281 (2015).

Boerigter, C., Campana, R., Morabito, M. & Linic, S. Evidence and implications of direct charge excitation as the dominant mechanism in plasmon-mediated photocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 7, 10545. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10545 (2016).

Boerigter, C., Aslam, U. & Linic, S. Mechanism of charge transfer from Plasmonic Nanostructures to chemically attached materials. ACS Nano. 10, 6108–6115. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.6b01846 (2016).

Chavez, S., Aslam, U. & Linic, S. Design principles for Directing Energy and energetic charge Flow in Multicomponent Plasmonic nanostructures. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 1590–1596. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.8b00841 (2018).

Zhou, L. et al. Aluminum nanocrystals as a Plasmonic Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Dissociation. Nano Lett. 16, 1478–1484. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b05149 (2016).

Brongersma, M. L., Halas, N. J. & Nordlander, P. Plasmon-induced hot carrier science and technology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2014.311 (2015).

Thomann, I. et al. Plasmon Enhanced Solar-to-Fuel Energy Conversion. Nano Lett. 11, 3440–3446. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl201908s (2011).

Swearer, D. F. et al. Heterometallic antenna – reactor complexes for photocatalysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 8916–8920 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1609769113

Jain, V., Kashyap, R. K. & Pillai, P. P. Plasmonic Photocatalysis: activating Chemical bonds through Light and Plasmon. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2200463. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202200463 (2022).

Kravets, V. G. & Grigorenko, A. N. New class of photocatalytic materials and a novel principle for efficient water splitting under infrared and visible light: MgB(2) as unexpected example. Opt. Express. 23, A1651–1663. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.23.0a1651 (2015).

Kravets, V. G., Thomas, P. A. & Grigorenko, A. N. Metallic binary alloyed superconductors for photogenerating current from dissociated water molecules using broad light spectra. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy. 9, 021201. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4979821 (2017).

Yousaf, A. et al. Exfoliation of Quasi-two-dimensional nanosheets of Metal Diborides. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 6787–6799. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c00394 (2021).

Nishino, H. et al. Formation mechanism of Boron-Based Nanosheet through the reaction of MgB2 with Water. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 10587–10593. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b02348 (2017).

Chaffar Akkari, F., Kanzari, M. & Rezig, B. Preparation and characterization of obliquely deposited copper oxide thin films. Eur. Phys. J. - Appl. Phys. 40, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1051/epjap:2007128 (2007).

Cioffi, A. G., Martin, R. S. & Kiss, I. Z. Electrochemical oscillations of nickel electrodissolution in an epoxy-based microchip flow cell. J. Electroanal. Chem. (Lausanne). 659, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2011.05.007 (2011).

Gorzkowski, M. T. et al. Electrochemical oscillations and bistability during anodic dissolution of Vanadium electrode in acidic media—part I. Experiment. J. Solid State Electrochem. 15, 2311–2320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-011-1463-z (2011).

Leenheer, A. J. & Atwater, H. A. Water-splitting photoelectrolysis reaction rate via microscopic imaging of evolved oxygen bubbles. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, B1290. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.3462997 (2010).

Kravets, V. G., Zhukov, A. A., Holwill, M., Novoselov, K. S. & Grigorenko, A. N. Dead Exciton Layer and Exciton Anisotropy of Bulk MoS2 extracted from optical measurements. ACS Nano. 16, 18637–18647. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.2c07169 (2022).

Das, S. K., Bedar, A., Kannan, A. & Jasuja, K. Aqueous dispersions of few-layer-thick chemically modified magnesium diboride nanosheets by ultrasonication assisted exfoliation. Sci. Rep. 5, 10522. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10522 (2015).

Huber, K. Molecular Spectra and Molecular Structure: IV. Constants of Diatomic Molecules (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Pandit, S. et al. Fabrication of hybrid Pd@Ag core-shell and fully alloyed bi-metallic AgPd NPs and SERS enhancement of rhodamine 6G by a unique mixture approach with graphene quantum dots. Appl. Surf. Sci. 548, 149252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149252 (2021).

Azzam, R. M. A. & Bashara, N. M. Ellipsometry and Polarized Light (North-Holland Publishing Company, 1977).

Kravets, V. G., Neubeck, S., Grigorenko, A. N. & Kravets, A. F. Plasmonic Blackbody: strong absorption of light by metal nanoparticles embedded in a dielectric matrix. Phys. Rev. B. 81, 165401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.81.165401 (2010).

Kravets, V. G. et al. Measurements of electrically tunable refractive index of MoS2 monolayer and its usage in optical modulators. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 3, 36. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-019-0119-1 (2019).

Kuz’menko, A. B. et al. Manifestation of multiband optical properties of MgB2. Solid State Commun. 121, 479–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-1098(02)00004-2 (2002).

Guritanu, V. et al. Anisotropic optical conductivity and two colors of MgB2. Phys. Rev. B. 73, 104509. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.73.104509 (2006).

Li, Z., Yang, J., Hou, J. G. & Zhu, Q. First-principles study of MgB2 (0001) surfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 65, 100507. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.65.100507 (2002).

García-Vidal, F. J., Pitarke, J. M. & Pendry, J. B. Effective medium theory of the optical properties of aligned carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 4289–4292 (1997).

Kravets, V. G. & Grigorenko, A. N. Retinal light trapping in textured photovoltaic cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3497646 (2010).

Malassis, L. et al. Topological darkness in self-assembled Plasmonic metamaterials. Adv. Mater. 26, 324–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201303426 (2014).

Cui, X. et al. Transient excitons at metal surfaces. Nat. Phys. 10, 505–509. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2981 (2014).

Kravets, V. G., Schedin, F. & Grigorenko, A. N. Plasmonic Blackbody: almost complete absorption of light in nanostructured metallic coatings. Phys. Rev. B. 78, 205405 (2008).

Kravets, V. G., Neubeck, S., Grigorenko, A. N. & Kravets, A. F. Plasmonic Blackbody: strong absorption of light by metal nanoparticles embedded in a dielectric matrix. Phys. Rev. B 81 (2010).

Ku, W., Pickett, W. E., Scalettar, R. T. & Eguiluz, A. G. Ab initio investigation of collective charge excitations in MgB2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 057001. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.057001 (2002).

Profeta, G., Continenza, A., Bernardini, F. & Massidda, S. Electronic and dynamical properties of the MgB2 surface: Implications for the superconducting properties. Phys. Rev. B. 66, 184517. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.66.184517 (2002).

Uchiyama, H. et al. Electronic structure of MgB2 from Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 157002. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.157002 (2002).

Grätzel, M. Photoelectrochemical cells. Nature 414, 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/35104607 (2001).

Aslam, U., Rao, V. G., Chavez, S. & Linic, S. Catalytic conversion of solar to chemical energy on plasmonic metal nanostructures. Nat. Catal. 1, 656–665. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-018-0138-x (2018).

Yan, L., Wang, F. & Meng, S. Quantum Mode selectivity of Plasmon-Induced Water Splitting on Gold nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 10, 5452–5458. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.6b01840 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The work was performed with the support of Graphene Flagship program, Core 3 (881603) and Royce ICP Round 3 project EP/X527257/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V. K. and A.G. initiated the project. V. K. fabricated devices, performed Photocatalytic tests and Ellipsometric and Raman measurements. A.G. analysed the data. V.K. and A.G. carried out the FTIR measurements. All authors discussed the results and contributed to writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article omitted the Abstract. The Abstract now reads: “Plasmonic nanostructures can help to drive chemical photocatalytic reactions powered by sunlight. These reactions involve excitation of plasmon resonances and subsequent charge transfer to molecular orbitals under study. Here we engineered photoactive plasmonic nanostructures with enhanced photocatalytic performance using non-noble metallic MgB2 high-temperature superconductor which represents a new family of photocatalysts. Ellipsometric study of fabricated MgB2 nanostructures demonstrates that this covalent binary metal with layered graphite-like structure could effectively absorb visible and infrared light by excitation of multi-wavelengths surface plasmon resonances. We show that a MgB2 plasmonic metal-based photocatalyst exhibit fundamentally different behaviour compared to that of a semiconductor photocatalyst and provides several advantages in photovoltaics applications. Excitation of localised surface plasmon resonances in MgB2 nanostructures allows one to overcome the limiting factors of photocatalytic efficiency observed in semiconductors with a wide energy bandgap due to the usage of a broader spectrum range of solar radiation for water splitting catalytic reactions conditioned by enhanced local electromagnetic fields of localised plasmons. Excitation of localised surface plasmon resonances induced by absorption of light in MgB2 nanosheets could help to achieve near full-solar spectrum harvesting in this photocatalytic system. We demonstrate a conversion efficiency of ~ 5% at bias voltage of Vbias = 0.3 V for magnesium diboride working as a catalyst for the case of plasmon-photoinduced seawater splitting. Our work could result in inexpensive and stable photocatalysts that can be produced in large quantities using a mechanical rolling mill procedure.”

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kravets, V.G., Grigorenko, A.N. Water and seawater splitting with MgB2 plasmonic metal-based photocatalyst. Sci Rep 15, 1224 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82494-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82494-5