Abstract

The promise of antiferromagnetic spintronics largely relies on the possibilities of electrical manipulation of antiferromagnetic states, which requires the exploration of innovative material platforms to meet the challenge. Erythrosiderite-type compounds constitute a class of non-oxide materials presenting magneto-electric couplings ranging from multiferroicity to linear magneto-electric behaviour. In this communication, we demonstrate that Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] shows evidence of another ferroic order, ferrotoroidicity, providing an alternative way of manipulating the magnetic states. The magnetic structure of this compound (a collinear antiferromagnet with moments along b) allows a toroidal moment in the ac-plane. We have used spherical neutron polarimetry on a single crystal of Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] cooled in different configurations of applied electric (E) and magnetic (H) fields to show that the toroidal domains can be selected by a conjugate field (ExH) coupling with the c-component of the toroidal moment. The extraordinary sensitivity of spherical neutron polarimetry allows detecting and quantifying this toroidal domain selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Four primary ferroic orders can be defined with respect to time-reversal and space inversion symmetries: (i) ferroelasticity, (ii) ferroelectricity, (iii) ferromagnetism, and (iv) ferrotoroidicity1,2,3. In the case of ferroelasticity, the alignment of strain is even under both time- and space-inversion symmetries; the alignment of electric dipoles leading to ferroelectricity breaks only the space inversion; in ferromagnetism, the time-reversal symmetry is broken by the aligned magnetic moments, but not the space-inversion. In the case of ferrotoroidicity, a toroidal moment T originated by a vortex of magnetic moments produces both time-reversal and space-inversion symmetry breaking4. The first three ferroic orders are the most widely known, while the fourth is much more elusive, and the number of materials where this order has been characterized remains reduced. This may be due, to some extent, to the fact that the experimental determination of ferrotoroidic order in a material is not as straightforward as for the other ferroic orders5. However, ferrotoroidic materials are decidedly promising for application in spintronics due to the possibilities they offer of electrical manipulation of antiferromagnetic states. Indeed, a direct relation is identified between switchable antiferromagnets and the ferrotoroidic order, both theoretically6 and experimentally (see, for example,3,7,8). This evidences the significance of investigations in ferrotoroidic compounds and the importance of expanding the range of materials that express ferrotoroidicity.

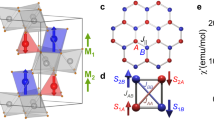

The majority of known ferrotoroidic materials involve transition metals in an octahedral crystal field and include oxoanions such as phosphate or silicate groups that help establishing the dimensionality of the magnetic exchange constants5. Here we present a compound with a different structural arrangement that, as we demonstrate, shows evidence of ferrotoroidicity. Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] belongs to the erythrosiderite-type family of compounds with general formula A2[FeX5(H2O)], where A stands for an alkali-metal or an ammonium ion, and X for a halide ion. This family of non-oxide materials shows examples of magneto-electric coupling ranging from multiferroicity in (NH4)2[FeCl5(H2O)]9,10 to linear magneto-electric behaviour in K2[FeCl5(H2O)], Rb2[FeCl5(H2O)] or Cs2[FeCl5(H2O)]11. Cs2[FeCl5(H2O)], and its deuterated analogue Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] display an orthorhombic crystal structure at room temperature (space group Cmcm) consisting of [FeCl5·D2O]2− ionic units that form distorted octahedrons, with a Fe3+ ion in the center, four Cl atoms in the equatorial plane, and the remaining Cl-atom and a water molecule occupying the apical positions (see Fig. 1). These units are connected along the c axis through an extensive network of H bonds (or D bonds for the deuterated compound), with the Cs+ counterions occupying the empty space and stabilizing the structure12,13. The title compound undergoes a phase transition below ca. 175 K (ca. 158 K for the hydrogenated analogue) implying the positional ordering of the water molecules, which results in a breaking of symmetry with a structural transformation from orthorhombic to monoclinic (I2/c space group), with an associated doubling of the c-axis. Below TN = 6.6 K, at zero applied magnetic field, magnetic ordering takes place, with magnetic propagation vector k = (0,0,0), adopting a collinear antiferromagnetic arrangement with moments along b and magnetic space group I2’/c12, as illustrated in Fig. 1. This magnetic structure is fully consistent with the linear magneto-electric behaviour of this compound11,13.

Interestingly, the symmetry of the system in the magnetically ordered phase is indeed consistent with ferrotoroidicity. The magnetic point group is 2’/m, which is included in the 31 out of the 122 Heesch-Shubnikov magnetic point groups that allow ferrotoroidicity (in this case pure ferrotoroidicity, not associated with ferromagnetism and/or ferroelectricity)5,14. Here, the inversion center is combined with time reversal, the magneto-electric tensor is constrained by symmetry to be non-diagonal with non-equal off-diagonal elements and, finally, the symmetry analysis shows that a ferrotoroidal moment, T, is allowed in the ac-plane15. From the point of view of the symmetry, this case is very similar to the ferrotoroidic compound MnPS3, with the same magnetic point group and also a toroidal moment allowed in the ac-plane16. Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] should present ferrotoroidic domains corresponding to antiferromagnetic 180º domains, which can be manipulated jointly by the application of combined magnetic (H) and electric (E) fields14.

As previously mentioned, ferrotoroidicity is not easy to prove experimentally. Among the different techniques employed to prove this physical property, such as second harmonic generation (SHG)3 or nonreciprocal directional dichroism17, spherical neutron polarimetry (SNP) stands as a powerful neutron scattering technique that allows proving ferrotoroidicity and quantifying ferrotoroidic domain population5. In a SNP experiment, neutron polarization matrices relating the scattered neutron polarization to the incoming one are measured for a number of Bragg reflections on single crystals that can be cooled under different applied H and E fields (see “Methods” section). Due to the sensitivity to the vectorial nature of the magnetic structure factor (and not only the modulus, like for unpolarized neutron diffraction) the off-diagonal terms of these matrices may express the ferrotoroidic domain population, which can be manipulated upon application of a conjugate E × H field along the toroidal moment direction. Here we have used SNP measurements on a crystal of Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] to prove ferrotoroidicity in this material, showing that the toroidal domains can be selected by a conjugate field applied along the c-component of the toroidal moment.

View of the crystal and magnetic structure of Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)], with the direction of the toroidal moment and of the applied electric and magnetic fields. The crystal structure at low temperature is I2/c with cell parameters a = 17.016 Å, b = 7.339 Å, c = 16.105 Å, α = γ = 90°, and β = 90.07°, and the magnetic structure, with magnetic propagation vector k = (0,0,0), corresponds to the Shubnikov magnetic space group I2’/c12. The iron, cesium, chlorine, oxygen, and deuterium ions have been represented in brown, light blue, green, red and gray, respectively; the magnetic moments are represented by the red arrows over the iron positions, and the direction of the toroidal moment is represented by a blue arrow.

Results and discussion

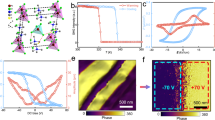

Following the method proposed by Ederer and Spaldin4, a significant volumic toroidic moment can be calculated in the unit cell of Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)]: T = (0.01746 0.00000 – 0.01804) µB Å−2 (details of this calculation can be found in the Supporting Information). Therefore, by cooling into the magnetically-ordered phase under a conjugate E × H field in the ac-plane, it should be possible to couple with the ferrotoroidal moment and create a ferrotoroidic domain imbalance. With this in mind, we performed different field-cooling procedures of a single crystal of Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)]. Starting from temperatures well above TN (typically ~ 30 K) we cooled down the sample well into the magnetically-ordered state (below 4 K) in an electric field of 8 kV cm−1 applied along the b axis (vertical) and a magnetic field of ± 0.7 T applied parallel to the a axis, before removing the magnetic field, placing the cryostat into the SNP device and measuring neutron polarization matrices for a series of magnetic Bragg reflections. The results for just a single reflection, (4 0 2), depicted in Fig. 2, immediately show that a nearly complete domain selection can be achieved, and that this selection can be reversed by changing the sign of the applied H field (and therefore the conjugate E × H field). The Pxy and Pyx neutron polarization matrix terms are directly sensitive to the toroidic domain population (see “Methods” section). Their absolute value close to 1 (ca. 0.8) is indicative of an almost complete population of one of the domains (97(1)% population), while the change of sign upon reversal of the conjugate field reveals the full population of the other domain, and therefore the complete switch of the domain populations. In contrast, when the sample is cooled under parallel E and H fields (E = 8 kV cm−1, H = 0.7 T both along b), i.e. E × H = 0, the Pxy and Pyx terms become zero (while the rest of the terms remain the same as in the other conditions), indicating an equal population of the magnetic domains (49(1)% population of one of the domains).

Observed (solid color columns and error bars) and calculated (black rectangles) neutron polarization matrix elements for the (4 0 2) reflection of a crystal of Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] oriented with b vertical. (Left) Sample cooled under an E field of 8 kV cm−1 applied along the b axis and a H field of 0.7 T parallel to the a axis (negative conjugate E x H field of – 5.6 T kV cm−1 along c). (Middle) Sample cooled under an E field of 8 kV cm−1 applied along b axis and a H field of 0.7 T parallel to the b axis (zero conjugate E x H field). (Right) Sample cooled under an E field of 8 kV cm−1 applied along the b axis and a H field of – 0.7 T parallel to the a axis (positive conjugate E x H field of 5.6 T kV cm−1 along c). For the calculations, the crystal and magnetic structure models from ref12. were used, with only the magnetic domain population allowed to vary, giving final values of 0.03/0.97(1), 0.49/0.51(1) and 0.97/0.03(1) for the negative, zero, and positive conjugate fields, respectively.

The full results of the SNP measurements in different poling conditions are displayed in Fig. 3. Complete polarization matrices of 10 magnetic reflections were measured after cooling under a negative conjugate E x H field of −5.6 T kV cm−1 along c. Starting from the crystal and magnetic structure models from ref.12, a fit with a minimal set of parameters allowing to vary only the magnetic domain population and the modulus of the magnetic moment (Fig. 3a) confirms the virtually complete population of one of the magnetic (ferrotoroidic) domains. The refined magnetic moments are slightly lower than those reported in ref.12, a tendency which is also observed in the fits corresponding to other poling conditions (see Fig. 3). Confirming the direct observations from the (4 0 2) reflection, the opposite nearly complete domain population is obtained for the fit of the polarization matrices of 5 magnetic reflections measured after cooling under a reversed conjugate E x H field of 5.6 T kV cm−1 along c (Fig. 3b). Finally, the domain population can be almost entirely balanced by cooling under parallel E and H fields, i.e. E × H = 0 (Fig. 3c, fit of the polarization matrices of 5 magnetic reflections). Zero-field cooling was also tested by measuring a limited number of polarization matrix elements, which were consistent with a nearly balanced domain population.

Observed versus calculated neutron polarization matrix elements for the different poling conditions. The error bars of the observed terms are of the size of the markers. a 10 full matrices measured after cooling under E field of 8 kV cm−1 along b and H field of 0.7 T along a (negative conjugate E x H field of -5.6 T kV cm−1 along c). b 5 full matrices measured after cooling under E field of 8 kV cm−1 along b and H field of -0.7 T along a (positive conjugate E x H field of 5.6 T kV cm−1 along c). c 5 full matrices measured after cooling under E field of 8 kV cm−1 and H field of 0.7 T, both along b (zero conjugate E x H field). d 8 full matrices measured after cooling under E field of 1.5 kV cm−1 along b and H field of 0.7 T along a (negative conjugate E x H field of -1.05 T kV cm−1 along c). For the calculations, the crystal and magnetic structure models from ref.12 were used, allowing to vary the magnetic domain population and the modulus of the magnetic moment, with the final values of the fit given in the figures.

Attempts to switch the domain population once into the magnetically ordered phase by reversing the E field where unsuccessful, even at temperatures close to TN, which indicates that the domains are strongly pinned once a crossed E x H field cooling is carried out. This is in contrast with the relatively easy switching of the cycloidal domains in the multiferroic member of this family (ND4)2[FeCl5(D2O)] at temperatures near TN10. However, the intensity of the conjugate field applied on cooling has an observable effect on the domain populations. When the sample is cooled under an E field of 1.5 kV cm−1 applied along the b axis and a H field of 0.7 T parallel to the a axis (negative conjugate E x H field of −1.05 T kV cm−1 along c), the domain population is not completely unbalanced, with the fit giving values of 0.165/0.835(7) for the population of the domains (Fig. 3d). Therefore, when plotting the domain populations or the directly observed Pxy value as a function of the intensity of the applied E x H field (Fig. 4), we retrieve a typical s-shaped curve commonly observed when manipulating ferroic domains with the appropriate field (see for example refs.5,18,19).

In conclusion, we have proposed a compound candidate for ferrotoroidicity, Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)], expanding the limited range of materials that express this property. This material belongs to the family of magneto-electric erythrosiderite-type compounds, which from the crystal chemistry point of view represent a different approach with respect to the majority of known ferrotoroidic materials5. Oxoanions are absent in these structures, with the octahedral coordination sphere around the magnetic atoms being formed by halide ions and water molecules, and there are no direct exchange coupling paths. The superexchange pathways are created by intermolecular hydrogen and halogen bonding rather than by traditional chemical bonds20. Compared with the more common oxides, these compounds display lower energy scales (which makes them particularly sensitive to external stimuli), offer tunable chemical architectures (for example, chemical substitution is an accessible and effective way to tune their physical properties), and present rich phase diagrams. Another interesting characteristic of these materials is that they are produced by accessible methods of solution chemistry at room-temperature. They crystallize easily and can be grown in thin films and surfaces by mild methods, which facilitates the incorporation in devices. Ferrotoroidicity adds another interesting ingredient to the rich playground of physical properties of the family of erythrosiderite-type compounds. We have shown that the magnetic structure of Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] allows a toroidal moment in the ac-plane, and we have used spherical neutron polarimetry on a crystal cooled under combined electric and magnetic fields to give evidence of its ferrotoroidicity. Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] presents ferrotoroidic domains corresponding to antiferromagnetic 180º domains, which we have been able to manipulate by the application of crossed fields E x H, obtaining a nearly complete domain selection. The variety of magneto-electric behaviours in the erythrosiderite family, together with the flexibility in the design of such compounds, allows speculating with the possibility of tuning the ferrotoroidicity by, for example, substitution of Cs by K/Rb, which may change the direction of the magnetic moments and possibly the orientation of the toroidal moment in the ac-plane. Due to the direct relation between electrically switchable antiferromagnets and the ferrotoroidic order6, ferrotoroidicity is a promising property for the development of spintronics.

Methods

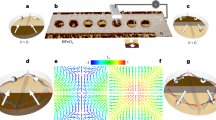

Spherical neutron polarimetry (SNP) measurements were performed on the D3 diffractometer at the Institut Laue–Langevin (ILL) using the Cryopad device21,22. The incident beam is polarized and monochromatized to 0.83 Å wavelength by Bragg reflection from the (111) planes of a ferromagnetic Heusler alloy crystal (Cu2MnAl). An erbium filter in the incident beam suppresses half-wavelength contamination. The direction of the incident and scattered beam polarization is controlled by means of nutators and precession fields, and a 3He spin filter is used to analyze the polarization of the scattered beam.

Full details of Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)] single-crystal preparation and characterization can be found in our previous work12. A prism-shaped crystal of Cs2[FeCl5(D2O)], with dimensions ca. 2 × 8 × 3 mm3 along the crystallographic a-, b- and c- directions (referred to the low temperature phase) was aligned with an accuracy better than 0.5 degrees using the neutron Laue diffractometer Orient Express23, and mounted onto a sample stick allowing the application of an electric field in the vertical direction. High voltage is applied by a potential difference between two parallel horizontal aluminum plates. The crystal was fixed to the lower plate by silver epoxy with the b axis being vertical, and with the upper plate positioned at 10 mm from the lower electrode. The aluminum sample chamber was indium-sealed and evacuated, and the ensemble placed in a thin tail cryostat. Next to the instrument, a magnetic field (horizontal or vertical) of up to 1 Tesla can be applied together with the electric field while cooling the crystal below the magnetic ordering temperature; then the magnetic field is switched-off (the electric field remaining applied) and the thin-tail cryostat is transferred to the Cryopad device to measure neutron polarimetry.

The scattering of a fully polarized incident neutron beam can be expressed by a polarization matrix with elements Pij (i, j = X, Y, Z), representing the polarization of the scattered beam in the direction i, for an incident beam polarized in the direction j. The Blume reference frame is used24, with the X-axis parallel to the scattering vector Q, the Z-axis perpendicular to the scattering plane (vertical in our case), and the Y-axis completing the right-hand set. For a full description of the most general polarization matrix with detailed explanation, see the supplementary material.

We used the Mag2Pol program25 for analyzing and fitting the spherical neutron polarimetry data. The polarization matrix components were corrected for the imperfect incident neutron beam polarization and the efficiency of the neutron spin-filter in the scattered beam. The spin-filter efficiency was monitored by measuring the polarization term Pzz on the (008) Bragg peak (with negligible magnetic contribution). The crystal and magnetic structure models from ref12 were used for the calculations. These models imply two structural monoclinic twins equally populated and two antiferromagnetic (ferrotoroidic) domains, related by a change of sign of the magnetic moment. Only the magnetic domain population was allowed to vary in the fits, while the twin population was kept fixed. In the present case, the off-diagonal components, Pxy/Pyx, are directly sensitive to the population of the antiferromagnetic domains.

Data availability

The neutron scattering data presented in this paper are available at ref.26 (D3 instrument, Institut Laue-Langevin, experiment 5-54-232).

References

Dubovik, V. M. & Tugushev, V. V. Toroid moments in electrodynamics and solid-state physics. Phys. Rep. 4, 145 (1990).

Spaldin, N. A. et al. The toroidal moment in condensed-matter physics and its relation to the magnetoelectric effect. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 20, 434203 (2008).

van Aken, B. B. et al. Observation of ferrotoroidic domains. Nature 449, 702 (2007).

Ederer, C. & Spaldin, N. A.. Towards a microscopic theory of toroidal moments in bulk periodic crystals. Phys. Rev. B 76, 214404 (2007).

Gnewuch, S. & Rodriguez, E. The fourth ferroic order: current status on ferrotoroidic materials. J. Solid State Chem. 271, 175–190 (2019).

Watanabe, H. & Yanase, Y. Symmetry analysis of current-induced switching of antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B. 98, 220412 (2018).

Zimmermann, A. S., Meier, D. & Fiebig, M. Ferroic nature of magnetic toroidal order. Nat. Commun. 5, 4796 (2014).

Godinho, J. et al. Electrically induced and detected Néel vector reversal in a collinear antiferromagnet. Nat. Commun. 9, 4686 (2018).

Ackermann, M., Brüning, D., Lorenz, T., Becker, P. & Bohatý, L. Thermodynamic properties of the new multiferroic material (NH4)2[FeCl5 (H2O)]. New. J. Phys. 15, 123001 (2013).

Rodríguez-Velamazán, J. A. et al. Magnetically-induced ferroelectricity in the (ND4)2[FeCl5(D2O)] molecular compound. Sci. Rep. 5, 14475 (2015).

Ackermann, M., Lorenz, T., Becker, P. & Bohatý, L. Magnetoelectric properties of A2[FeCl5(H2O)] with A= K, Rb, Cs. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 26, 506002 (2014).

Fabelo, O. et al. Origin of the magnetoelectric effect in the Cs2FeCl5·D2O compound. Phys. Rev. B. 96, 104428 (2017).

Fröhlich, T. et al. Structural and magnetic phase transitions in Cs2[FeCl5(H2O)]. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 30, 295403 (2018).

Schmid, H. Some symmetry aspects of ferroics and single phase multiferroics. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20(43), 434201 (2008).

Gallego et al. Automatic calculation of symmetry-adapted tensors in magnetic and non-magnetic materials: a new tool of the Bilbao Crystallographic Server. Acta Cryst. A 75, 438–447 (2019).

Ressouche, E. et al. Magnetoelectric MnPS3 as a candidate for ferrotoroidicity. Phys. Rev. B. 82, 100408 (2010).

Kimura, K., Otake, Y. & Kimura, T. Visualizing rotation and reversal of the Néel vector through antiferromagnetic trichroism. Nat. Commun. 13, 697. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28215-w (2022).

Radaelli, P. G. et al. Electric field switching of antiferromagnetic domains in YMn2O5: a probe of the multiferroic mechanism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 067205 (2008).

Hearmon, A. J. et al. Electric field control of the magnetic Chiralities in ferroaxial multiferroic RbFe(MoO4)2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 237201 (2012).

Hughey, K. D. et al. High-field magnetoelectric and spin-phonon coupling in multiferroic (NH4)2[FeCl5·(H2O)]. Inorg. Chem. 61, 3434–3442 (2022).

Tasset, F. et al. Spherical neutron polarimetry with Cryopad-II. Phys. B 268, 69 (1999).

Leliévre-Berna, E. et al. Advances in spherical neutron polarimetry with Cryopad. Phys. B Condens. Matter 356, 131–135 (2005).

Ouladdiaf, B. et al. OrientExpress: a new system for Laue neutron diffraction. Phys. B, 385–386, 1052 (2006).

Blume, M. Polarization effects in the magnetic elastic scattering of slow neutrons. Phys. Rev. 130, 1670 (1963).

Qureshi, N. Mag2Pol: a program for the analysis of spherical neutron polarimetry, flipping ratio and integrated intensity data. Phys. B 52, 175–185 (2019).

Rodríguez-Velamazán, J. A. et al. Spherical neutron polarization analysis of the magneto-electric Cs2[FeCl5·D2O]. Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL). https://doi.org/10.5291/ILL-DATA.5-54-232 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank N. Ayape Katcho for help with the calculation of the toroidal moment, and S. Vial for the technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.R.V. and O.F. conceived and carried out the experiments. The SNP data analysis was performed by J.A.R.V. and N.Q. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Velamazán, J.A.R., Fabelo, Ó. & Qureshi, N. Ferrotoroidicity in Cs2FeCl5·D2O. Sci Rep 14, 31204 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82505-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82505-5