Abstract

To investigate the correlation between fetoplacental circulation and maternal left ventricular myocardial work (MW) parameters in patients with preeclampsia (PE) and the prediction of fetal hypoxia. Seventy-eight PE patients (PE group) were assigned to intrauterine-hypoxia (27) and non-intrauterine-hypoxia (51) groups, and 45 healthy pregnant women were controls. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve evaluated the diagnostic efficacy of each parameter for fetal intrauterine hypoxia. Relative to the controls and the non-intrauterine-hypoxia group, the umbilical artery (UA) S/D, PI, and RI, as well as the global work index (GWI), global effective work, and global ineffective work, increased in the PE group and intrauterine-hypoxia group (P < 0.05), respectively, while the cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) and global work efficiency decreased (P < 0.05). Relative to the controls group, the middle cerebral artery S/D, PI, and RI decreased in the PE group (P < 0.05). Correlation analysis showed that the fetoplacental circulation parameters were correlated with MW parameters (P < 0.05), and CPR achieved the highest correlation. ROC curves showed that UA-S/D, combined with GWI, produced the highest predictive value for fetal hypoxia in PE patients. There was a linear correlation between MW parameters and fetoplacental parameters, and CPR showed the highest correlation with MW. UA-S/D, combined with GWI, exhibited optimal diagnostic efficacy in predicting fetal intrauterine hypoxia in PE patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are various theoretical explanations for the pathophysiological mechanism underlying preeclampsia (PE). Some scholars speculate that genetic susceptibility and environmental factors lead to placental maladaptation in PE, resulting in invasive trophoblast apoptosis and insufficient spiral artery remodeling that produce ischemia and hypoxia1. There is a synergistic coexistence between mother and fetus during pregnancy. The pressure or volume overload2 in PE is superimposed upon the maternal-fetal closed loop circuit3, and this gradually aggravates overall maternal and fetal circulatory function, promotes the development of intrauterine hypoxia, and leads to adverse pregnancy outcomes4. Investigators previously only monitored a single vessel in the fetal circulation or examined a small number of vessels to evaluate the intrauterine condition of the fetus5,6,7, which lacked the clinically applicative value of combining the maternal heart with the fetal circulation. Relevant studies have shown that left ventricular myocardial work (LV-MW) obtained by constructing pressure-strain loops (PSLs) constitutes a sensitive index for evaluating maternal cardiac function in PE patients8. Therefore, we will herein assess the sensitive indices of maternal cardiac function and a combination of fetoplacental circulatory parameters, and probe their application in PE patients with fetal intrauterine hypoxia, aiming to correlate the two. This could potentially inform early intervention by clinicians and provide evidence for appropriate diagnosis and treatment plans.

Materials and methods

Study population

A total of 78 patients with PE2 who were treated in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital between October 2022 and October 2023 were selected as the case group (PE group). This group was aged 22–44 years, with an average age of 31.52 ± 4.01 years and an average gestational age of 34.50 ± 3.66 weeks (range, 29–39 weeks). There were six cases of intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR). The inclusion criteria for PE were based on the “Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy (2020)”2 and included maternal systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg after 20 weeks of gestation; urine protein (24-h) quantitation ≥ 0.3 g, urine protein/creatinine ≥ 0.3, or random urine protein ≥ (+); being without proteinuria but with involvement of any organ or system; or placenta-fetus involvement. According to the clinical standard for fetal intrauterine hypoxia9, the PE group was further divided into an intrauterine-hypoxia group (hypoxia group, 27 cases) and non-intrauterine hypoxia group (non-hypoxia group, 51 cases). In the intrauterine hypoxia group, there were nine cases of abnormal fetal heart rate, seven cases of abnormal fetal monitoring, four cases of abnormal fetal movement, five cases of amniotic fluid contamination, seven cases of postpartum Apgar score < 7 and birth weight < 2500 g, and six cases of IUGR, with some patients showing more than two abnormal indicators.

The diagnostic criteria for fetal intrauterine hypoxia9 are:

-

(1)

Abnormal fetal heart rate: repeated detection of a fetal heart rate ≥ 160 beats/min or ≤ 120 beats/min;

-

(2)

Recurrent late deceleration or severe variable deceleration in fetal heart rate monitoring;

-

(3)

Abnormal fetal movement: fetal movement > 10 times/h or < 10 times/12 h;

-

(4)

Meconium-stained amniotic fluid (grade II or above), amniotic fluid index < 8 cm, or maximum depth < 3 cm;

-

(5)

Apgar score < 7 at 1 min and 5 min after delivery or birth weight < 2500 g.

Possessing at least one of the above criteria was considered indicative of fetal intrauterine hypoxia.

Another 45 healthy pregnant women were randomly selected as the control group, with an average age of 32.54 ± 4.37 years (range 24–47 years) and an average gestational age of 34.78 ± 2.29 weeks (range 31–38 weeks). None of the patients experienced cardiopulmonary disease before pregnancy, and we noted no cases of fetal chromosomal abnormalities or developmental malformations.

Apparatus and methods

Instrumentation

The instrument we employed was a GE Voluson E10, GE Vivid E95 color Doppler ultrasound diagnostic instrument. The probe we used was the M5Sc-D, C1-5-D, operating at frequencies of 3.0–5.0 MHz and 1.4–4.6 MHz, and it was equipped with a post-processing EchoPAC203 workstation.

The duration of fetal examination was maintained under 30 min, and the data were collected by two doctors with more than 10 years of work experience in obstetrical and gynecologic ultrasonography and who were at the level of associate chief physician or above.

Acquisition of fetoplacental circulation parameters

For image acquisition, we placed the patient in a supine position, ensuring they were breathing calmly, and collected the following parameters during fetal quiescence: umbilical artery (UA) systolic/diastolic ratio (S/D), resistance index (RI), pulsatility index (PI); and middle cerebral artery (MCA)-S/D, MCA-RI, and MCA-PI. We also calculated the cerebroplacental ratio (CPR).

Acquisition and processing of maternal LV-MW parameters

We instructed the subjects to lie on their left sides and we connected them to simultaneous electrocardiography. We acquired dynamic grayscale images of more than three cardiac cycles, including apical four-chamber, two-chamber, and three-chamber views. The images were analyzed using EchoPAC 203, in which clear endocardial visualization of the apical three-chamber, four-chamber, and two-chamber dynamic images were selected. Automatic functional imaging mode was then entered to automatically identify the myocardial regions of interest. We manually adjusted unsatisfactory delineation areas, and accessed the Myocardial Work mode within the BE + Traces interface. We confirmed aortic valve closure time, inputted the brachial artery blood pressure, and clicked “Approve” to automatically compute pressure-strain loops (PSLs), global work index (GWI), global constructive work (GCW), global wasted work (GWW), and global work efficiency (GWE).

Statistical analysis

We applied SPSS 25.0 software to analyze our data. Tests of normality for continuous variables were performed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and measurement data followed a normal distribution and are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. We executed t-tests for comparisons between groups. The measurement data that did not follow a normal distribution are expressed as median (interquartile range), and we employed the Mann–Whitney U test for group comparisons. The correlation between two variables was assessed using Pearson and Spearman correlation analyses. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed, and we calculated the area under the ROC curve (AUC), with optimal cutoff values used to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of each parameter with respect to fetal intrauterine hypoxia in PE patients. Comparison of the AUC was performed using the DeLong test. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethical considerations

All procedures were carried out in accordance with guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital (approval number, 2024-77), and all patients provided informed consent.

Results

Comparison of clinical features in this study

Compared to the control group, the PE group had a higher SBP, DBP, and incidence of IUGR, as well as a lower neonatal weight (P < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in the other parameters (Table 1).

Comparisons of fetoplacental circulation parameters and MW parameters between the control and PE groups

Compared to the control group, the PE group showed significantly increased UA-S/D, UA-PI, UA-RI, GWI, GCW, and GWW and reduced MCA-S/D, MCA-PI, MCA-RI, CPR, and GWE (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Comparison of fetoplacental circulation parameters and MW parameters between the hypoxia and non-hypoxia groups of PE patients

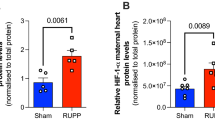

UA-S/D, UA-PI, UA-RI, GWI, GCW, and GWW were significantly elevated, while CPR and GWE were diminished in the hypoxia group compared to the non-hypoxia group (P < 0.05). MCA-S/D, MCA-PI, and MCA-RI did not differ between groups (P > 0.05) (Table 3; Fig. 1).

(A) Non-invasive LV pressure-strain loop diagram. The area within the loop is estimated as global MW. (B) Bull’s eye plot of MW in pre-eclampsia with intrauterine hypoxia (GLS, − 17%; GWI, 2472 mmHg%; GCW, 3043 mmHg%; GWW, 322 mmHg%; GWE, 90%; BP, 170/110 mmHg); the red area represents a significant increase in GWI at the apex. (C) Bar graph of GCW and GWW in preeclampsia patients with intrauterine hypoxia. LV left ventricle, GLS global longitudinal strain, MW myocardial work, GWI global work index, GCW global constructive work, GWW global wasted work, GWE global work efficiency, BP blood pressure.

Correlation analysis

UA (S/D, PI, and RI) showed positive correlations with GWI, GCW, and GWW and negative correlations with GWE, while MCA (S/D, PI, and RI) and CPR exhibited negative correlations with GWI, GCW, and GWW and positive correlations with GWE (Table 4).

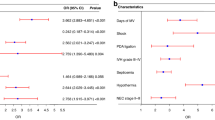

ROC curve analysis

Our analysis of fetoplacental circulation parameters depicted UA-S/D as having the largest AUC at 0.744, with a cutoff value of 3.06, sensitivity of 0.531, and specificity of 0.978 (Table 5); this index reflected the highest diagnostic value.

ROC curve analysis of MW parameters showed that GWI had the largest AUC of 0.835, and exhibited the highest diagnostic value at a cutoff value of 2060.00 mmHg%, with a sensitivity of 0.905 and specificity of 0.700.

The integration of UA-S/D and GWI yielded a higher diagnostic performance than individual predictors, with an AUC of 0.896, sensitivity of 0.796, and specificity of 0.901 (Table 5; Fig. 2).

Discussion

Doppler parameters of UA flow not only reflect the downstream placental circulatory resistance, but also abnormalities in fetal blood circulation10. In normal pregnancy, the placental vascular bed increases, placental perfusion rises significantly, and resistance declines11; thus, the UA-S/D, UA-PI, and UA-RI gradually fall with gestational age12. However, due to placental dysfunction, the intra-placental circulatory resistance in PE patients rises13, while the UA-S/D, UA-PI and UA-RI also increase. In severe cases, the end-diastolic flow of UA disappears and reverses. In the present study, the values of UA-S/D, UA-RI, and UA-PI in the PE group were significantly higher than values in the control group (Table 2), and the values of UA-S/D, UA-RI, and UA-PI in PE patients in the hypoxia group were significantly elevated compared to those in the non-hypoxia group (Table 3). In PE patients, the muscular arterioles distributed in the placental villous layer are significantly reduced and the maturity of the placental villous tree is altered, causing vasospasm and stenosis, placental insufficiency, diminished placental perfusion, and augmented UA resistance14. Studies have revealed that with the deterioration in placental function, the release of related inflammatory factors increases and the dynamic balance of angiogenic factors and anti-angiogenic factors is disturbed, resulting in endothelial dysfunction and an increase in arterial stiffness in PE patients15. When fetal intrauterine hypoxia occurs, placental histological and functional damage enters the terminal stage, resulting in insufficient fetal blood and oxygen supplies1; consequently, UA resistance further increases.

In normal pregnancy, the MCA reflects a state of elevated resistance throughout gestation, reaches a peak at approximately 28 weeks, and gradually decreases thereafter16. When intrauterine hypoxia occurs, the fetus manifests reduced cardiac output by triggering a “brain protective effect” to avoid significant tissue damage, and it conducts a “redistribution” of circulating blood to maintain the tasks performed by brain, heart, and adrenal gland17. MCA-S /D, MCA-PI, and MCA-RI in the PE group in our study were significantly lower than those in the control group (Table 2), indicating that the “cerebral protective effect” was operational in the fetuses of PE patients18, and with vascular dilatation of the cerebral bed, the resistance of the MCA subsequently decreased. There was, however, no significant difference in MCA-S /D, MCA-PI, or MCA-RI between the PE patients with hypoxia and those without (Table 3). We postulate that the reasons for this are two-fold: (1) The authors have ascertained that with the gradual aggravation of fetal intrauterine hypoxia, cerebral edema, loss of blood-flow distribution, and decompensation due to the " cerebral protective effect” occur, the MCA cannot maintain cerebral blood supply through expansion. The MCA resistance index initially declines with dilation but then eventually increases once the compensatory mechanisms fail19, resulting in “pseudo-normalization.” In severe cases, this result can lead to absent or reversed diastolic blood flow20. (2) In PE patients with systemic arteriolar spasm and stenosis, increased circulatory resistance (even without fetal intrauterine hypoxia) raises the incidence of an abnormal MCA spectrum compared to that of healthy pregnant women19. In conclusion, therefore, the evaluation of fetal intrauterine hypoxia in PE patients by MCA Doppler index alone has certain limitations.

CPR is a response parameter of the cerebral protective effect of arterial blood redistribution during fetal hypoxia, and is closely related to fetal oxygen partial pressure21. In normal pregnancy, the Doppler indices of the UA are lower than in the MCA, and there is a dynamic balance between the resistance indices of the UA and MCA22. The PE group in the current study showed that CPR was significantly lower than those in the control group (Table 2), and the indices in the hypoxia groups were significantly lower than in the non-hypoxia group (Table 3). We hypothesize that when PE and fetal intrauterine hypoxia occur, the diastolic flow velocity of the UA decreases and PI increases. In contradistinction, due to the “cerebral protective effect” and “redistribution of blood circulation,” the diastolic flow velocity of the MCA rises and PI drops, which leads to a diminution in CPR. Therefore, CPR can be used as a sensitive index for the diagnosis of PE and fetal intrauterine abnormalities that cause hypoxia.

McClements23 found that maternal functional and metabolic adaptations to early angiogenic impairment preceded fetal cardiac metabolic changes in a rat model of PE. We herein also found that, with respect to MW parameters, GCW, GWI, and GWW were significantly higher in the PE group compared to the control group and in the hypoxia group compared to the non-hypoxia group, while GWE was decreased (Tables 2 and 3). We posit that the reasons for this are threefold: (1) PE patients trigger angiogenic disorders and reduced myocardial perfusion through the up-regulation of FKBPL expression24. This causes concentric remodeling of myocardial tissue, and ventricular wall stress and oxygen consumption increase accordingly25. Furthermore, Sahiti26 et al. confirmed that patients with LV concentric hypertrophy had higher GCW and GWI. (2) In PE patients, coronary artery spasm causes segmental contraction of the myocardium, uncoordinated ventricular motion, decreased synchrony, and reduced LV effective ejection volume27,28; GWW therefore rises to a greater extent than GCW, leading to a drop in GWE. (3) When fetal hypoxia occurs, the body ensures the blood supply to important fetal organs through neurohumoral regulation, and fetoplacental circulatory resistance and maternal afterload increase6, leading to a further increase in MW.

There are no extant reports on correlation analyses between MW parameters and fetoplacental circulation parameters in China or elsewhere. In previous studies, most PE patients were studied using fetal circulatory system or maternal cardiac function assessment alone. Recently, Maseliene29 investigated the correlation between maternal hemodynamic parameters (cardiac output and peripheral vascular resistance) and the umbilical artery, finding that reduced maternal cardiac output and increased maternal peripheral vascular resistance are associated with elevated fetal umbilical artery impedance. This study reinforces the link between maternal cardiovascular function and observations of fetal circulation. Our study further examined the relationship between maternal cardiac function and fetal circulation and found that UA Doppler parameters were significantly correlated with maternal MW parameters (Table 4). Notably, the UA-PI exhibited a better fit with MW than UA-S/D and UA-RI, potentially because the calculation formula for UA-PI included not only UA peak and valley velocity, but also UA mean velocity over the entire cardiac cycle. The Doppler parameters of the MCA were negatively correlated with GWI, GCW, and GWW and positively correlated with GWE (Table 4). An increase in MCA Doppler parameters can indicate an increase in maternal GWE and a decrease in GWI, GCW, and GWW. Importantly, CPR showed the highest correlation coefficient with each MW parameter (Table 4), indicating that the combination of multiple vessels more comprehensively represented the changes in fetoplacental circulation and maternal MW. Our observed decrease in CPR in PE and in hypoxia suggests that the maternal heart needs to perform more work in order to meet the energy demands of the body and the fetus. The reason for this is that when chemoreceptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch sense fetal hypoxia, they induce the constriction of peripheral vessels and a decrease in the fetal heart rate, redistributing blood flow in the fetus. Additionally, metabolic adaptation to reduced substrate delivery further reduces oxygen consumption30,31; however, placental insufficiency leads to increased placental circulatory resistance, and maternal cardiac work increases due to increased cardiac afterload in PE patients. The underlying mechanism for this still requires further exploration, however.

The sensitivity of MW parameters in our ROC curve analysis was higher (Table 5), indicating that MW parameters reflected a heightened ability to identify fetal intrauterine hypoxia in PE patients, whereas the specificity of fetoplacental circulation parameters was higher, indicating that these indices possessed a more robust ability to detect a lack of intrauterine hypoxia in PE patients. Therefore, we combined the two parameters to predict fetal intrauterine hypoxia in PE patients, with GWI exhibiting the optimal diagnostic value among MW parameters and UA-S/D serving as the best indicator of fetal circulation parameters. The AUC of the combination of the two parameters was the largest, and was superior to that of either single index.

Limitations

There are three main limitations to our methodology: (1) the sample size was small, and the cutoff values for some indicators therefore need to be further verified by enlarging the sample; (2) gestational age was not further subdivided and was limited to the third trimester; and (3) ultrasonographic detection was affected by factors such as the thickness of the maternal abdominal wall and fetal position, resulting in some errors occurring that could affect the generalizability of the results. We recommend that, in the future, investigators should monitor the entire pregnancy period, subdivide their gestational age range, engender multi-center cooperation, and expand the sample size.

Conclusions

We observed a linear correlation between MW parameters and fetoplacental circulation indices, among which CPR exhibited the highest correlation with MW parameters. Furthermore, ROC curve analysis showed that UA-S/D, combined with GWI, possessed the best diagnostic efficacy in predicting fetal intrauterine hypoxia in PE patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ives, C. W., Sinkey, R., Rajapreyar, I., Tita, A. & Oparil, S. Preeclampsia-pathophysiology and clinical presentations: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 1690–1702 (2020).

Agrawal, A. & Wenger, N. K. Hypertension during pregnancy. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 22, 64 (2020).

Gyselaers, W. & Lees, C. Maternal low volume circulation relates to normotensive and preeclamptic fetal growth restriction. Front. Med. 9, 902634 (2022).

Gyselaers, W. Hemodynamic pathways of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226, S988–S1005 (2022).

Schmidt, L. J. et al. A machine-learning–based algorithm improves prediction of preeclampsia-associated adverse outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 227, 71–77 (2022).

Reddy, M. et al. Role of placental, fetal and maternal cardiovascular markers in predicting adverse outcome in women with suspected or confirmed pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 59, 596–605 (2022).

Tudor, A. et al. The role of uterine artery Doppler in the second and third trimesters for prediction of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction developed as a consequence of placental-mediated diseases. Curr. Health Sci. J. 49, 251–256 (2023).

Chan, J. et al. A new approach to assess myocardial work by non-invasive left ventricular pressure-strain relations in hypertension and dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. -Cardiovasc. Imaging. 20, 31–39 (2019).

Browne, V. A. et al. Uterine artery blood flow, fetal hypoxia and fetal growth. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 370, 20140068 (2015).

Bligard, K. H. et al. Clinical significance of umbilical artery intermittent vs persistent absent end-diastolic velocity in growth-restricted fetuses. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 227, 511–519 (2022).

Harris, L. K. et al. Placental bed research: II. Functional and immunological investigations of the placental bed. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 221, 457–469 (2019).

Lin, X. et al. Evaluation of Doppler indices (MCA & UA) and fetal outcomes: a retrospective case-control study in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 36, 2183471 (2023).

Kawasaki, K. et al. Metabolomic profiles of placenta in preeclampsia. Hypertension 73, 671–679 (2019).

Jena, M. K. et al. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia and therapeutic approaches targeting the placenta. Biomolecules 10, (2020).

Perry, H. et al. Maternal arterial stiffness in hypertensive pregnancies with and without small-for-gestational-age neonate. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 56, 44–50 (2020).

Wolf, H., Stampalija, T. & Lees, C. C. Fetal cerebral blood-flow redistribution: analysis of Doppler reference charts and association of different thresholds with adverse perinatal outcome. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 58, 705–715 (2021).

Su, H. et al. In utero hypoxia altered ANG II-induced contraction via PKCβ in fetal cerebral arteries. J. Endocrinol. 244, 213–222 (2020).

Ali, S. et al. Middle cerebral arterial flow redistribution is an indicator for intrauterine fetal compromise in late pregnancy in low-resource settings: a prospective cohort study. Bjog 129, 1712–1720 (2022).

Stampalija, T. et al. Fetal cerebral doppler changes and outcome in late preterm fetal growth restriction: prospective cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 56, 173–181 (2020).

Vollgraff, H. C. et al. Publication bias may exist among prognostic accuracy studies of middle cerebral artery doppler ultrasound. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 116, 1–8 (2019).

Morales Roselló, J., Bhate, R., Eltaweel, N. & Khalil, A. Comparison of ductus venosus Doppler and cerebroplacental ratio for the prediction of adverse perinatal outcome in high-risk pregnancies before and after 34 weeks. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. (2023).

Palacio, M. et al. Reference ranges for umbilical and middle cerebral artery pulsatility index and cerebroplacental ratio in prolonged pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 24, 647–653 (2004).

McClements, L. et al. Impact of reduced uterine perfusion pressure model of preeclampsia on metabolism of placenta, maternal and fetal hearts. Sci. Rep. 12, 1111 (2022).

Todd, N. et al. Role of a novel angiogenesis FKBPL-CD44 pathway in preeclampsia risk stratification and mesenchymal stem cell treatment. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 106, 26–41 (2021).

McNally, R. et al. Non-viral gene delivery utilizing RALA modulates sFlt-1 secretion, important for preeclampsia. Nanomedicine 16, 1999–2012 (2021).

Sahiti, F. et al. Left ventricular remodeling and myocardial work: results from the population-based STAAB cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 669335 (2021).

Leon, L. J. et al. Preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease in a large UK pregnancy cohort of linked electronic health records: a caliber study. Circulation 140, 1050–1060 (2019).

Ghossein-Doha, C., Hooijschuur, M. & Spaanderman, M. Pre-eclampsia: A twilight zone between health and cardiovascular disease? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 12–16 (2018).

Maseliene, T. et al. Alterations in maternal cardiovascular parameters and their impact on uterine and fetal circulation in hypertensive pregnancies and fetal growth restriction. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev. 22, 200316 (2024).

Zhu, M. Y. et al. The hemodynamics of late-onset intrauterine growth restriction by Mri. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 214, 361–367 (2016).

Cetin, I. et al. Fetal oxygen and glucose consumption in human pregnancy complicated by fetal growth restriction. Hypertension 75, 748–754 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Te authors are grateful for the support of the entire staf of Department of Ultrasound, Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D., L.W.: contributed to designed the study and wrote the manuscript. J.D., W.L.: contributed to the conception of the study. J.Z., W.L.: data collection. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, J., Zhao, J., LI, W. et al. Diagnostic value of combined maternal cardiac work and fetoplacental circulation parameters in detecting fetal intrauterine hypoxia in preeclamptic women. Sci Rep 14, 31209 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82545-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82545-x