Abstract

This study evaluates the growth, survival pressures, and community dynamics of Barringtonia racemosa (L.) Spreng. populations in Jiulong Mountain and Suixi County, Guangdong Province. Six distinct plant communities were identified, with human disturbances significantly disrupting natural succession processes. The population in Jiulong Mountain, particularly within the Talipariti tiliaceum-B. racemosa community (JLS-T), experienced higher survival pressures compared to Suixi County. Interspecific competition varied, with species like Derris trifoliata, T. tiliaceum, and invasives such as Ipomoea cairica and Mikania micrantha exerting substantial pressure on B. racemosa. Analysis of 234 B. racemosa individuals revealed significant correlations between diameter at breast height (DBH), plant height, and age structure distribution, with a linear relationship between DBH and height underscoring their relevance in understanding wood volume, biomass, and stand structure. Survival pressures were inversely related to DBH, indicating reduced competition as trees matured. Growth patterns exhibited an age-dependent plateau in height, potentially influenced by environmental and anthropogenic factors. Management strategies should prioritize the growth of individuals with DBH less than 5 cm (age classes I ~ II). These findings underscore the need for targeted conservation efforts to protect B. racemosa communities and sustain wetland ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plant-plant competition is a fundamental process that shapes the structure and dynamics of ecological communities1, influencing individual growth, population dynamics, and community structure within natural plant communities2,3,4. Understanding the factors governing tree growth and mortality is crucial for predicting stand dynamics, assessing forest productivity, and effective forest ecosystem management5. Competition among plants impacts the distribution of essential resources such as light, water, and nutrients, influencing radial growth and survival outcomes6. Within a stand, plants follow specific growth patterns, competing for resources within defined spatial limits as they develop7.

Research by Wang et al.8 and Zhang et al.9 has demonstrated the significant impact of interspecific competition on the survival of endangered plant species, highlighting the role of competition dynamics in plant community resilience. Neighbor competition has been linked to increased tree mortality risk, emphasizing its contribution to individual tree outcomes10. Studies like that of Yang et al.2 have indicated that the influence of competition intensity on tree growth may change as trees progress through developmental stages.

Barringtonia racemosa (L.) Spreng. is an evergreen tree in the genus Barringtonia of the family Lecythidaceae. This semi-mangrove species is valued for its ecological importance, ornamental appeal, and medicinal properties11,12,13,14, However, it is currently endangered due to habitat degradation and loss, leading to its classification as an endangered species in China’s Red List of Biodiversity for Higher Plants by the IUCN15. Found in coastal regions from eastern Africa to Southeast Asia and beyond, B. racemosa thrives in limited mainland Chinese communities, notably in Guangdong Province16,17,18,19. However, there has been a trend of population decline20. Liang et al.21,22,23 demonstrated that B. racemosa exhibits remarkable adaptability to flooding and salinity stress. Furthermore, their findings revealed that this species possesses a strong capacity to accumulate heavy metals, particularly cadmium and lead, making it highly effective for remediating heavy metal-contaminated environments and contributing to environmental protection24. The plant’s physiological processes, root systems25, and bioactive compounds make it vital for ecosystem stabilization and pharmacological applications, particularly in traditional medicine and wetland restoration26. Tan et al.27 predicted the global suitable habitat range for B. racemosa and identified temperature and precipitation as key environmental factors influencing its distribution. However, the conservation efforts for B. racemosa in China remain insufficient. Given its ecological importance and current conservation status, it is essential to understand the survival pressures faced by B. racemosa populations to inform conservation strategies and promote the sustainable management of China’s forests. This study aims to investigate these pressures within mainland Chinese B. racemosa communities using a neighborhood interference model, considering factors such as tree height and diameter at breast height (DBH) to better understand the species’ challenges and support conservation efforts.

Materials and methods

Plot overview and setting

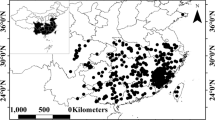

Currently, the distribution of natural populations of B. racemosa in the Chinese mainland is limited to two regions, exhibiting a relatively dispersed pattern. In order to ensure representativeness, a comprehensive field inspection was conducted from January to March 2023. As a result, the Mangrove National Wetland Park in Jiulong Mountain, Haikang County, Leizhou City, Guangdong Province, and the Tiaofeng River and Cheng-yue River in Suixi County, Zhanjiang City were selected for on-site investigations. These investigations focused on the regions where wild B. racemosa populations are found along both sides of the rivers. The region’s geographic location can be found in Fig. 1 and Table 1 for detailed information.

The map is based on the approval number GS (2024) 0650 for China’s map shp file, with data sourced from the National Geoinformation Public Service Platform (https://www.tianditu.gov.cn/); (B): Locations of sample sites SX-1, SX-2, SX-3, SX-4, SX-5, and SX-6 in Suixi County; (C): Locations of sample sites JLS-1, JLS-2, and JLS-3 in Haikang County. The satellite images in Figures (B) and (C) were downloaded from the 91 Satellite Map Assistant (https://www.91weitu.com). The maps were created using ArcGIS version [10.8.1] (https://www.esri.com/).

Species composition and classification of plant community types

This study employed a conventional sampling method (Table 1) to select three plots within the Mangrove National Wetland Park of Jiulong Shan, taking into consideration the dispersed distribution of the B. racemosa community in its natural habitat. The dominant species found in the park include Talipariti tiliaceum, Pongamia pinnata, and Heritiera littoralis. Similarly, three sample plots were chosen from the B. racemosa forest located along the banks of the Tiaofeng River in Chiling, Guantian Village, Suixi County. The primary associated species in this area consist of Sonneratia apetala, Acrostichum aureum, and Acanthus ilicifolius. Two sample plots were selected from Chengyue River bank in the Xibian Village Group. The main associated species of B. racemosa were S. apetala, T. tiliaceum, A. ilicifolius, A. aureum and Derris trifoliata. One sample plot was selected at the tidal gully of the Chengyue River in Xipo Village, and the main associated species were P. pinnata, T. tiliaceum, Pandanus tectorius, A. aureum, S. apetala. A total of nine plots were established, consisting of eight plots measuring 10 m × 10 m (JLS-1, JLS-3, SX-1, SX-2, SX-3, SX-4, SX-5, SX-6) and one plot measuring 5 m × 20 m (JLS-2). All tree species within the sample plots with a DBH of 2.5 cm or greater were measured, with both DBH and height recorded. For understory plants with a DBH less than 2.5 cm, we recorded the species name, number of individuals, and height. DBH was measured at a height of 1.3 m using a caliper, and plant height was determined using a laser range finder with a precision of 1 m. The coordinates (x, y) of each tree were recorded with the lower left corner of the sample plots serving as the origin (0, 0). The coordinate values were expressed using quadrat projection distance and assigned unique numbers to prevent duplication.

Simultaneously, a variety of environmental data were collected, including latitude and longitude, slope position, slope, and slope direction (Table 1). As indicated in Table 1, the study area’s latitude and longitude span from 20°39′26.69"N/110°16′56.64"E to 21°9′44.17"N/110°8′9.25"E. The slope positions consist of uphill, middle, and downhill, with slope values ranging from 0.75 to 5.76. The slope direction in the survey area is mostly east and south.

Identification of plant species and canopy closure measurement methods

To ensure accurate identification of plant species within the surveyed plots, we invited Professor He Taiping, an expert in plant taxonomy from Guangxi University, to formally classify all recorded species. Simultaneously, specimens of B. racemosa were collected from various communities for further analysis. A voucher specimen of the collected B. racemosa (catalogued as YLSY-BR002) has been securely deposited in the Characteristic Medicinal Plant Herbarium of Southeast Guangxi at Yulin Normal University (coordinates: N22°41’, E110°12’).

For measuring canopy closure, we adopted the mechanical point sampling method as described by Wang Xuefeng et al.28. This approach involves establishing N sample points within the forest stand in a systematic manner during field surveys. At each sample point, the observer assesses the vertical view upward to determine whether the tree canopy covers the point. Sample points covered by the canopy are counted, while uncovered points are excluded. The proportion of points covered by the canopy (n) relative to the total number of sample points (N) is then used to calculate the stand’s canopy closure (fcc) using the following formula:

Determination of competition index

This study examines the calculation method for determining the individual survival pressure of a rare and endangered tree species, as outlined by Wang et al.8 and Zhang et al.9. In contrast to the Hegyi single tree competition model29 and Zhang Yuexi’s improved neighborhood interference model30, this approach takes into account the distance between the endangered species and competitive plants, along with other crucial tree measurement factors including plant height and DBH. The specific formula utilized is as follows:

Individual survival pressure index of rare and endangered tree species from a competing tree (PIij):

In the formula, PIij is the survival pressure index of a single tree, that is, the survival pressure of the “i” individual of rare and endangered tree under the “j” competing tree, PIij ≥ 0; Dj is the DBH (arborous species, in cm) or cover area (shrub/herb/vine, in m2) of the “j” competing tree; Di is the DBH of the “i” individual of rare and endangered tree species, and the unit is cm. Hj is the height of the “j” competing tree (unit: m); Lij is the distance between the “j” competing tree and the “i” individual of rare and endangered tree species, in m; Hi is the plant height of the “i” individual of rare and endangered tree species, the unit is m ; When the plant height (H) of a certain tree species is greater than or equal to the distance(L) from the rare and endangered tree species, the plant is identified as a competing tree.

The survival pressure index of rare and endangered tree species from a competing tree species (PIit):

In the formula, PIit is the interspecific survival pressure index, that is, the survival pressure of the “i” individual of rare and endangered tree species from competing tree species “t”; PIij is the survival pressure index of individual tree, that is, the survival pressure of individual tree “i” of rare and endangered species from the competing tree “j” of “t”; “m” is the number of competing trees of competing species “t”.

The survival pressure index of rare and endangered tree species from all competing tree species (PIi):

In the formula, PIi is the survival pressure index, that is, the survival pressure of the “i” individual of rare and endangered tree species from all competing tree species; PIit is the survival pressure index among species, that is, the survival pressure of the “i” species of rare and endangered species from competing species “t”. “n” is the total number of competing tree species.

Diameter class structure

Due to the challenge of accurately determining the individual age of B. racemosa population, numerous studies have employed the approach of substituting the age structure of standing wood with DBH, thereby replacing time with space, to ascertain the population age31. We utilized the diameter class classification method proposed by Zhong et al.20 to examine the diameter class structure of B. racemosa. Accordingly, B. racemosa seedlings with DBH < 2.5 cm were categorized as the first age grade, while for plants with DBH ≥ 2.5 cm, each incremental increase in DBH corresponded to one additional age grade. To enhance the research process, the age groups I and II are categorized as low age levels, while the age groups III to VII are classified as middle age levels, and the age groups VIII to X are designated as senior levels. The DBH ranges of each age class are shown in Table 2.

Differential analysis of survival pressure between species and communities

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using SPSS 19.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to assess the variability in survival pressure (PIi) experienced by B. racemosa across different community settings. Multiple comparisons were performed using Duncan’s test at a significance level of 5% (P < 0.05). Linear regression analysis of plant height and DBH, as well as linear and nonlinear analysis of DBH and survival pressure (PIit), were conducted using OriginPro 2021 9.8.5.201 (OriginLab Inc., Northampton, MA, USA) to establish a relationship model between the two variables.

Results

The growth of B. racemosa in the study area

To accurately assess the survival pressure (PIi) of the B. racemosa population, samples were chosen based on the age structure characteristics of the B. racemosa population in Jiulong Mountain and Suixi County of Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province. A total of 234 ramets of B. racemosa were examined in this study, with a minimum DBH of 4.00 cm, a maximum DBH of 40.00 cm, and an average DBH of 11.37 cm. The height of the smallest tree measured 2.20 m, the largest tree measured 4.50 m, and the average tree height was 2.896 m. Table 2 displays the distribution of individuals across different age grades. Notably, age grades II, III, and IV had a higher number of individuals, total 208 ramets, which accounted for 27.35%, 27.78%, and 33.76% of the total, respectively. Conversely, age grades I and X had no individuals present. The distribution characteristics of age classes are shown in Table 2.

DBH and plant height are crucial variables in the assessment of single wood volume, biomass, and stand structure32. This study identified a strikingly linear relationship between these two factors (y = 2.164x + 0.064, R2 = 0.61408, P = 1.80004E-127). Overall, the study area exhibited a high abundance of young (II, III) and middle (IV) B. racemosa, with noticeable growth in plant height. However, in the mature tree stage, there was a tendency for tree height growth to plateau as DBH increased (Fig. 2).

Types of plant communities distributed in B. racemosa

The study identified six plant community types (Table 3), including mangrove and semi-mangrove vegetation such as B. racemosa, P. pinnata, T. tiliaceum, S. apetala, A. aureum, and A. ilicifolius, alongside invasive species like C. odorata and M. micrantha. In Suixi County, the SX-B community had the highest canopy density (0.9–0.95), while SX-A and SX-AI communities were the sparsest (0.2–0.3). The classification of anthropogenic disturbance severity, based on the study by Wang et al.8 and our field investigation results, is divided into two categories: slight and severe. Jiulong communities (JLS-B and JLS-T) experienced minimal disturbance, preserving ecological stability, whereas Suixi’s B. racemosa populations faced severe disruption from tree felling, sand extraction, and aquaculture development, hindering natural succession and ecological balance.

Survival pressure of B. racemosa in different community types

The survival pressure of B. racemosa population in B. racemosa (JLS-B and SX-B) community

According to the data presented in Tables 4, 5, and 6, it is evident that the interspecific survival pressure (PIi = 56.79) within the B. racemosa community located in Jiulong mountain (JLS-B), Leizhou City, surpasses that observed in the Suixi County community (SX-B, PIi = 19.30 and 14.64). However, it is worth noting that the B. racemosa intraspecific survival pressure index (PIij) in all three plots remains relatively low, with PIij values of only 2.67, 2.08, and 3.27. In the JLS-B community, A. glandulosa var. kulingensis and P. montana exhibited a large area of crown coverage among the competing trees, accounting for 50% and 28% respectively. Additionally, the PIit values generated by these two trees were significantly higher (25.67 and 17.29 respectively) compared to the other four competing trees (P < 0.05, Table 4). Similarly, in the SX-B community of Suixi County, D. trifoliata, M. micrantha, and I. cairica displayed higher PIit values compared to the other competing trees (Tables 5 and 6).

The survival pressure of the B. racemosa population in the T. tiliaceum-B. racemosa (JLS-T) community

In the JLS-T community, a comprehensive examination was conducted on a total of 15 B. racemosa sample trees. The primary source of survival pressure (PIi) experienced by these sample trees in the community emanated from 10 competing trees, namely T. tiliaceum, P. montana, A. heterophyllus, D. trifoliata, C. nucifera, P. foetida, H. littoralis, B. racemosa, P. pinnata, and C. odorata. The PIi reached a remarkable value of 83.35, while the B. racemosa intraspecific survival pressure index (PIij) was merely 1.25. Among the various trees in competition, T. tiliaceum accounted for 61.54% of the population, with a population pressure index (PIit) of 39.85. Additionally, P. montana twisted constituted 30.00% of the canopy area, with a corresponding PIit of 21.80. Notably, the survival pressure experienced by these two species was significantly greater compared to the remaining eight species of competing trees (P < 0.05, Table 7).

The survival pressure of B. racemosa population in B. racemosa-A. aureum (SX-A) community

In the community of SX-A, a total of five B. racemosa sample trees were examined. The primary source of survival pressure, as measured by the survival pressure index (PIi), was attributed to seven competing trees: D. trifoliata, I. cairica, A. aureum, B. racemosa, E. camaldulensis, P. karka, and C. odorata. The calculated PIi value was 44.89, while B. racemosa intra-specific survival pressure index (PIij) was only 0.65. Notably, D. trifoliata encompassed 30% of the tree crown area, resulting in the highest survival pressure contribution with a PIit value of 33.76. This value significantly surpassed that of the other six competing trees (P < 0.05, Table 8).

The survival pressure of the B. racemosa population in the S. apetala-B. racemosa (SX-S) community

In the SX-S community, a total of five B. racemosa sample trees were examined. The community consisted of nine species of competing trees, including S. apetala, D. trifoliata, I. cairica, T. tiliaceum, A. aureum, E. camaldulensis, B. racemosa, C. odorata, and P. karka. The combined survival pressure index (PIi) of these species was 42.13. Among the competing trees, the proportion of S. apetala was 40.00%. These trees exhibited a significantly higher survival pressure index (PIit = 21.86) compared to the other eight competing trees (P < 0.05, Table 8). Secondly, the canopy area occupied by D. trifoliata and I. cairica accounted for 22.00% and 4.00% respectively. The proportion of T. tiliaceum trees was 10.00%. The impact of these three competing trees on B. racemosa did not show any significant difference, with PIit values of 7.58, 6.31, and 3.78 respectively. Furthermore, the B. racemosa intraspecies competition pressure was minimal, as indicated by a PIij value of only 0.33 (Table 9).

The survival pressure of the B. racemosa population in the B. racemosa-A. ilicifolius (SX-AI) community

In the SX-AI community, a study was conducted on eleven sample trees of B. racemosa. The survival pressure experienced by these trees was primarily attributed to competition from nine other species, namely D. trifoliata, M. micrantha, S. apetala, I. cairica, B. racemosa, E. camaldulensis, A. aureum, A. ilicifolius, and P. karka. The total survival pressure index for these competing species was calculated to be 23.88. The interspecific survival pressure index, as generated by D. trifoliata, M. micrantha, S. apetala, and I. cairica, exhibited a significantly higher value when compared to the remaining five competing trees. Notably, D. trifoliata and M. micrantha displayed the greatest survival pressure, accounting for 25.00% and 20.00% of the crown area, respectively, with corresponding indices (PIit) of 7.35 and 5.61, no significant difference was observed (Table 10).

The survival pressure of the B. racemosa population in the P. pinnata-T. tiliaceum-B. racemosa (SX-P) community

In the SX-P community, a study was conducted on a total of eight B. racemosa sample trees. The survival pressure (PIi) experienced by these plants primarily originated from 10 competing trees, namely T. tiliaceum, M. micrantha, S. apetala, D. trifoliata, P. pinnata, I. cairica, P. tectorius, B. racemosa, A. aureum, and P. karka. The calculated value for PIi was 39.37. Furthermore, the intraspecies competition pressure (PIij) for B. racemosa was found to be relatively small, with a value of only 0.63. T. tiliaceum and S. apetala comprised 37.50% and 5.00% of the competing trees, respectively, while the canopy area of vine M.micrantha and D. trifoliata encircling B. racemosa accounted for 15.00% and 10.00%, respectively. The resulting survival pressure PIit exerted by these four competing trees on B. racemosa individuals was significantly higher than that of other competitors, with values of 11.83, 7.94, 7.21, and 4.18 (P < 0.05, Table 11).

Comparison of survival pressure (PI i) in six community types

A one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons revealed significant variations in survival pressure PIi across the six community types. Specifically, the survival pressure of the B. racemosa population in Jiulong mountain exhibited a significantly higher value compared to that in Suixi County. Notably, the JLS-T community displayed the highest survival pressure, which was significantly greater than the other five communities (P < 0.05, Fig. 3). Despite the absence of notable disparities in the survival pressure (PIi) among the SX-A, SX-S, and SX-P communities, both of which exhibited significantly higher survival pressures compared to the SX-B and SX-AI communities (P < 0.05), the SX-B community displayed the lowest survival pressure for B. racemosa (Fig. 3).

Comparison of survival pressure in six community types. JLS-B: Jiulong mountain B. racemosa community; SX-B: Suixi county B. racemosa community; JLS-T: Jiulong mountain T. tiliaceum-B. racemosa community; SX-A: Suixi county B. racemosa-A. aureum community; SX-S: Suixi county S. apetala-B. racemosa community; SX-AI: Suixi county B. racemosa-A. ilicifolius community; SX-P: Suixi county P. pinnata-T. tiliaceum-B. racemosa community.

Furthermore, as evidenced by the data presented in Table 12, the cumulative survival pressure index resulting from interspecific competition among various communities on the individual within the study area can be ranked as follows: D. trifoliata (PIit = 75.98) > T. tiliaceum (PIit = 55.46) > P. montana (PIit = 39.09) > S. apetala (PIit = 33.16) > A. glandulosa var. kulingensis (PIit = 25.67) > I. cairica (PIit = 27.96) > M. micrantha (PIit = 23.81). These seven dominant competing tree species collectively accounted for 78.48% ~ 93.14% of the survival pressure experienced by all examined communities, among which the local vine D. trifoliata showed competition in all communities, especially in SX-A community. The pressure (PIit) generated by D. trifoliata on B. racemosa was as high as 33.76, followed by T. tiliaceum, which was the pressure (PIit) generated by T. tiliaceum on B. racemosa in JLS-T community was as high as 39.85. The invasive species I. cairica also appeared in most of the communities, and its pressure was also high, with a total PIit of 27.96.

The influence of interspecific survival pressure (PI it) on radial growth of B. racemosa

The results depicted in Fig. 4 demonstrate a significant negative linear correlation between individual DBH and interspecific survival pressure (PIit), particularly in the JLS-B and SX-B communities, as well as the JLS-T communities (P < 0.05, Fig. 4A, B). The Pearson correlation coefficients for these communities were -0.36 and -0.31, respectively. Additionally, nonlinear analysis revealed a Gaussian Modified (GaussMod) function relationship between PIit and DBH in the JLS-B and SX-B communities (Table 13), with PIit starting to decline when DBH exceeded 5cm (Fig. 5A). In the JLS-T, SX-AI, and SX-P communities, a Gauss function relationship was observed between PIit and DBH (Fig. 5B, E, F, Table 13). Specifically, when the DBH exceeded 6 cm, 12 cm, and 10 cm in the respective communities, PIit exhibited a decline. Additionally, in the SX-A community, the relationship between PIit and DBH followed a Logistpk function (Table 13), with PIit declining when the DBH exceeded 10 cm (Fig. 5C). Similarly, in the SX-S community, the relationship between PIit and DBH was characterized by an Extreme function (Table 13), with PIit declining when the DBH exceeded 6cm (Fig. 5D).

Relationship between population pressure and individual DBH in different communities (linear analysis). DBH: Diameter at breast height; R: Relative coefficient; P: P value; Red dots indicated all B. racemosa individuals, purple area indicated 95% prediction intervals. A: Jiulong mountain B. racemosa community and Suixi county B. racemosa community (JLS-B and SX-B); B: Jiulong mountain T. tiliaceum-B. racemosa community (JLS-T); C: Suixi county B. racemosa-A. aureum community (SX-A); D: Suixi county S. apetala-B. racemosa community (SX-S); E: Suixi county B. racemosa-A. ilicifolius community (SX-AI); F: Suixi county P. pinnata-T. tiliaceum-B. racemosa community (SX-P).

Relationship between population pressure and individual DBH in different communities (nonlinear analysis). Red dots indicated all B. racemosa individuals, purple area indicated 95% prediction intervals. DBH: Diameter at breast height; A: Jiulong mountain B. racemosa community and Suixi county B. racemosa community (JLS-B and SX-B); B: Jiulong mountain T. tiliaceum-B. racemosa community (JLS-T); C: Suixi county B. racemosa-A. aureum community (SX-A); D: Suixi county S. apetala-B. racemosa community (SX-S); E: Suixi county B. racemosa-A. ilicifolius community (SX-AI); F: Suixi county P. pinnata-T. tiliaceum-B. racemosa community (SX-P).

Discussion

Plant-plant competition and community dynamics

The interplay of competition among plant species is a pivotal factor shaping the structure and dynamics of ecological communities33,34. Plant-plant competition influences individual growth, population dynamics, and overall community structure by determining the distribution of essential resources such as light, water, and nutrients. The competition for these resources significantly impacts radial growth and survival outcomes, especially in resource-limited environments. Research highlights that competition is often more pronounced in nutrient-poor habitats, driving the adaptation and resilience of plant species through evolutionary processes35,36. Slope, a key environmental factor, affects plant growth, species distribution, and seedling regeneration by influencing water, nutrients, soil stability, and light37,38. This study found that slope variations impacted the growth and density of B. racemosa. In areas with gentle slopes (0.75°), B. racemosa had larger DBH and greater tree heights, suggesting favorable conditions for growth due to better moisture retention and nutrient accumulation, especially in mangrove wetlands. In contrast, steeper slopes (5.76°) showed smaller individuals and lower plant density, likely due to increased water and nutrient loss. Additionally, most slopes in the study area faced southeast, suggesting that sunlight availability may also influence B. racemosa distribution.

In the context of B. racemosa, a semi-mangrove species of significant ecological importance, understanding these competitive interactions is crucial27. Our studies have shown that the competition dynamics can vary significantly across different stages of plant development and among various plant communities. For instance, younger and middle-aged B. racemosa individuals may exhibit different competitive behaviors compared to mature trees, reflecting changes in resource allocation and growth patterns35. In B. racemosa communities (JLS-B and SX-B), the survival pressure on individuals decreased significantly once their DBH exceeded 5 cm, corresponding to the transition from age class II to III (Figs. 4A and 5A). This reduction in survival pressure continued, and when the DBH surpassed 12 cm (age class IV), the survival pressure across different populations became minimal and tended to stabilize. These findings indicate that as the DBH (and age class) of B. racemosa individuals increases, the survival pressure they experience decreases correspondingly.

Interspecific competition and survival pressure

Interspecific competition, where different species vie for the same resources, plays a crucial role in determining the survival and distribution of plant species39,40. In the study area, the interspecific competition for B. racemosa was found to be significantly influenced by the presence of other competing species such as D. trifoliata, T. tiliaceum, and invasive species like I. cairica and M. micrantha. These species often dominate the available resources, thereby exerting high survival pressures on B. racemosa populations.

The survival pressure index (PIi) used in this study quantifies the impact of these competitive interactions41. High PIi values indicate intense competition, which can lead to reduced growth rates and increased mortality. For example, in Jiulong Mountain (JLS-B), the PIi for B. racemosa was significantly higher compared to other locations, suggesting a more competitive environment. This high competition can lead to a reduction in B. racemosa populations if the species cannot adapt or find a niche that minimizes competitive pressures.

Impact of habitat degradation and human activities

Human activities and habitat degradation exacerbate the competitive pressures on plant communities42,43,44. In the case of B. racemosa, deforestation, land conversion for agriculture, and other anthropogenic disturbances have significantly altered its habitat, leading to increased competition for the remaining resources. These activities disrupt natural succession processes, making it difficult for B. racemosa to establish and maintain stable populations.

The study highlighted that in areas with significant human disturbance, such as Suixi County, the competitive pressures from invasive species and other competing plants were more pronounced. These findings underscore the need for effective conservation strategies that mitigate the impact of human activities on sensitive plant communities. Restoration efforts should focus on reducing invasive species and restoring natural habitats to support the resilience and recovery of endangered species like B. racemosa.

Role of facilitation in plant communities

While competition is a major driver of plant community dynamics, facilitation positive interactions between plants also plays a critical role, especially in harsh environments35,45. Facilitation can enhance the survival and growth of certain species by ameliorating stressful conditions, such as extreme temperatures or nutrient-poor soils.

In B. racemosa communities, facilitation may occur through interactions with other semi-mangrove species that help stabilize the soil and improve nutrient availability. Understanding the balance between competition and facilitation is essential for developing comprehensive conservation strategies. By promoting facilitative interactions, it is possible to enhance the resilience of B. racemosa populations against competitive pressures and environmental changes.

Conservation implications and future research

The findings from this study have important implications for the conservation and management of B. racemosa and other endangered plant species. Effective conservation strategies must account for the complex interplay of competition and facilitation within plant communities46,47. This involves protecting critical habitats, controlling invasive species, and promoting conditions that support positive plant interactions.

Future research should focus on exploring the mechanisms underlying these interactions and how they are influenced by environmental changes such as climate change. Long-term studies are needed to monitor the impact of conservation interventions and to adapt management practices based on evolving ecological dynamics. Additionally, integrating traditional ecological knowledge with scientific research can provide valuable insights into sustainable management practices that benefit both biodiversity and local communities.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author, as they are not publicly accessible due to privacy concerns.

Change history

28 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90546-7

References

Mayfield, M. M. & Levine, J. M. Opposing effects of competitive exclusion on the phylogenetic structure of communities. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1085–1093. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01509.x (2010).

Yang, T. et al. Effect of neighborhood competition on key tree species growth in broadleaved-Korean pine mixed forest in Changbai Mountain, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 30 (2019).

Weiner, J. Asymmetric competition in plant populations. Trends Ecol. Evolut. 5, 360–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(90)90095-U (1990).

Yokozawa, M., Kubota, Y. & Hara, T. Effects of competition mode on spatial pattern dynamics in plant communities. Ecol. Model. 106, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(97)00181-6 (1998).

Condit, R. et al. The importance of demographic niches to tree diversity. Science 313, 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1124712 (2006).

Aleinikovas, M., Linkevičius, E., Kuliešis, A., Rolhle, H. & Schroeder, J. The impact of competition for growing space on diameter, basal area and height growth in pine trees. Baltic For. 20 (2014).

Weiner, J. Neighbourhood interference amongst Pinus Rigida individuals. J. Ecol. 72, 183–195. https://doi.org/10.2307/2260012 (1984).

Wang, Y. et al. Survival pressure of endangered species Phellodendron amurense. J. Beijing For. Univ. 43, 49–57. https://doi.org/10.12171/j.1000-1522.20200130 (2021).

Zhang, J., Guo, Z., Qian, Z., Lv, Y. & Cui, G. Survival pressure of a rare and endangered plant natural population of Pinus sylvestris var. Sylvestriformis. Acta Ecol. Sin. 41, 9581–9592. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb202103180724 (2021).

Weiskittel, A., Hann, D., Kershaw, J. & Vanclay, J. Forest Growth and Yield Modeling. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119998518 (2011).

Lin, P. Ecological Notes on mangroves in southeast coast of China including Taiwan province and Hainan island. Acta Ecol. Sin. 1, 283–290 (1981).

Tsay, J., Ko, P.-H. & Chang, P.-T. Carbon storage potential of avenue trees: a comparison of Barringtonia racemosa, Cyclobalanopsis glauca, and Alnus formosana. J. For. Res. 26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-015-0058-4 (2015).

Aluri, J. S. R., Palathoti, S., Banisetti, D. & Samareddy, S. Pollination ecology characteristics of Barringtonia racemosa (L.) Spreng. (Lecythidaceae). Transylv. Rev. Systematical Ecol. Res. 21, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.2478/trser-2019-0017 (2019).

Kong, K. W., Mat-Junit, S., Ismail, A., Aminudin, N. & Abdul-Aziz, A. Polyphenols in Barringtonia racemosa and their protection against oxidation of LDL, serum and haemoglobin. Food Chem. 146, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.012 (2014).

Qin, H. et al. Threatened species list of China’s higher plants. Biodivers. Sci. 25, 696–744. https://doi.org/10.17520/biods.2017144 (2017).

Lim, T. K. in Edible Medicinal And Non Medicinal Plants: Volume 3, Fruits (ed T. K. Lim) 114–121 (Springer Netherlands, 2012).

Orwa, C., Mutua, A., Kindt, R., Jamnadass, R. & Simons, A. Agroforestree Database: A Tree Reference and Selection Guide, version 4.0. World Agroforestry Centre ICRAF, Nairobi, KE (2009).

Zawawi, D. D., Ali, A. & Jaafar, H. Effects of 2,4-D and kinetin on callus induction of Barringtonia racemosa leaf and endosperm explants in different types of Basal Media. Asian J. Plant Sci. 12, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajps.2013.21.27 (2013).

Li, L. et al. Research on hydroponic seedling technology of endangered semi-mangrove plant Barringtonia racemosa. Contemp. Horticult. 46, 11–14. https://doi.org/10.14051/j.cnki.xdyy.2023.12.059 (2023).

Zhong, J. et al. Dynamic of Barringtonia racemosa population in Jiulongshan Mangrove NationalWetland Park, Leizhou. Wetland Sci. 16, 231–237. https://doi.org/10.13248/j.cnki.wetlandsci.2018.02.018 (2018).

Liang, F. et al. Growth and physiological responses of semi-mangrove plant Barringtonia racemosa to waterlogging and salinity stress. Guihaia 41, 872–882. https://doi.org/10.11931/guihaia.gxzw202007036 (2021).

Liang, F. et al. Responses of Barringtonia racemosa to tidal flooding. Fujian J. Agricult. Sci. 35, 1346–1356. https://doi.org/10.19303/j.issn.1008-0384.2020.12.008 (2020).

Liang, F. et al. Physiological response of endangered semi-mangrove Barringtonia racemosa to salt stress and its correlation analysis. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 39, 12–18. https://doi.org/10.14067/j.cnki.1673-923x.2019.10.003 (2019).

Liang, F. et al. New evidence of semi-mangrove plant Barringtonia racemosa in soil clean-up: Tolerance and absorption of lead and cadmium. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 12947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912947 (2022).

Hu, J. et al. Mechanism of salt tolerance in the endangered semi-mangrove plant Barringtonia racemosa: anatomical structure and photosynthetic and fluorescence characteristics. 3 Biotech 14, 103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-024-03943-6 (2024).

Dubey, V. K. et al. Single and repeated dose (28 days) intravenous toxicity assessment of bartogenic acid (an active pentacyclic triterpenoid) isolated from Barringtonia racemosa (L.) fruits in mice. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 3, 100057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2021.10.004 (2022).

Tan, Y. et al. Climate change threatens Barringtonia racemosa: Conservation insights from a MaxEnt model. Diversity 16, 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16070429 (2024).

Wang, X. & Lu, Y. Modern Forest Measurement Methods 20–22 (China Forestry Publishing House, 2013).

Hegyi, F. A simulation model for managing jack-pine stands. In: Growth Models for Tree and Stand Simulation (1974).

Zhang, Y. Application and improvement of the neighborhood interference model. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 352–357 (1993).

Jiang, E. Research on Structural characteristics at stumpage class of natural population of Rhododendron simiarum in Tianbaoyan National Nature Reserve, Fujian Province. South China For. Sci. 4–7. https://doi.org/10.16259/j.cnki.36-1342/s.2011.05.001 (2011).

Ducey, M. J. & Knapp, R. A. A stand density index for complex mixed species forests in the northeastern United States. For. Ecol. Manag. 260, 1613–1622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.08.014 (2010).

Wang, X., Peron, T., Dubbeldam, J. L. A., Kéfi, S. & Moreno, Y. Interspecific competition shapes the structural stability of mutualistic networks. Chaos Solitons Fractals 172, 113507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2023.113507 (2023).

Gruntman, M., Gross, D., Majekova, M. & Tielborger, K. Decision-making in plants under competition. Nat. Commun. 8, 2235. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02147-2 (2017).

Simon, J. & Schmidt, S. Editorial: Plant competition in a changing world. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 651. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00651 (2017).

Violle, C. et al. Competition, traits and resource depletion in plant communities. Oecologia 160, 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-009-1333-x (2009).

Liu, J. et al. Effect of clipping on aboveground biomass and nutrients varies with slope position but not with slope aspect in a hilly semiarid restored grassland. Ecol. Eng. 134, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2019.05.005 (2019).

Yang, Q. et al. Topography and soil content contribute to plant community composition and structure in subtropical evergreen-deciduous broadleaved mixed forests. Plant Divers. 43, 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2021.03.003 (2021).

Bolte, A. & Villanueva, I. Interspecific competition impacts on the morphology and distribution of fine roots in European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.). Eur. J. For. Res. 125, 15–26 (2006).

Aerts, R. Interspecific competition in natural plant communities: Mechanisms, trade-offs and plant-soil feedbacks. J. Exp. Bot. 50, 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/50.330.29 (1999).

Zhang, J., Liu, F. & Cui, G. One kind of rare and endangered species of individual survival pressure calculation method (2015).

Banks-Leite, C., Ewers, R. M., Folkard-Tapp, H. & Fraser, A. Countering the effects of habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation through habitat restoration. One Earth 3, 672–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.11.016 (2020).

Mao, C., Ren, Q., He, C. & Qi, T. Assessing direct and indirect impacts of human activities on natural habitats in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from 2000 to 2020. Ecol. Indic. 157, 111217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.111217 (2023).

Patrão, A. Human and Social Dimensions of Wildland Fire Management and Forest Protection. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (2020).

Hortal, S. et al. Plant-plant competition outcomes are modulated by plant effects on the soil bacterial community. Sci. Rep. 7, 17756. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18103-5 (2017).

Akesson, A. et al. The importance of species interactions in eco-evolutionary community dynamics under climate change. Nat. Commun. 12, 4759. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24977-x (2021).

Likens, G. E. & Lindenmayer, D. B. Integrating approaches leads to more effective conservation of biodiversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 21, 3323–3341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-012-0364-5 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We extend our profound appreciation to Professor He Taiping of Guangxi University for his invaluable assistance in plant identification. Additionally, our sincere gratitude goes to the management and technical staff of Jiulongshan Mangrove National Wetland Park in Leizhou, Guangdong, for their indispensable on-site support throughout the course of this investigation.

Funding

This research was funded by “The Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province, China, grant number 2022GXNSFBA035540”, “The National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 31660226”, “The Project for Enhancing Young and Middle-aged Teachers’ Research Basic Ability in colleges of Guangxi, grant numbers 2024KY0591”, “The Special Project for Basic Scientific Research of Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, grant number Gui Nongke 2024YP134 and 2024YP135”, and The Science and Technology Foundation of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, grant number Guike AD23026080. “The Special Project for Basic Scientific Research of Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, grant number Gui Nongke 2021YT143”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L. and X.T.; methodology, J.H.; software, X.T. and B.L.; formal analysis, F.L. and B.L.; investigation, Y.Y., Z.M. and L.L.; data curation, Z.M and Z.X.; writing-original draft preparation, F.L. and Y.L.; writing-review and editing, X.T and J.H.; supervision, F.L. and J.H.; project administration, F.L., X.T., Y.Y., L.L. and Y. L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in Figure 1 where the labels SX-2, SX-1, SX-3, SX-4, SX-5, and SX-6 were duplicated in panel (B). In addition, the Keywords section in the original version of this Article was incorrect. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, F., Hu, J., Lin, Y. et al. Interspecific competition and survival pressures in endangered Barringtonia racemosa populations of Mainland China. Sci Rep 14, 31190 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82572-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82572-8