Abstract

Visible and Near-infrared hyperspectral imaging (VNIR-HSI) combined with machine learning has shown its effectiveness in various detection applications. Specifically, the quality of cigar tobacco leaves undergoes subtle changes due to environmental differences during the air-curing phase. This study aims to evaluate the feasibility of deep learning methods in overcoming data limitations to develop a VNIR-HSI prediction model for the quality of cigar tobacco leaves at different air-curing levels. The moisture, chlorophyll, total nitrogen, and total sugar content in cigar tobacco leaves were predicted across various air-curing stages and light conditions. Results showed that the Diversified Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (DR-CNN) achieved the best performance, with a root mean square error of prediction for moisture at 3.109%, chlorophyll at 0.883 mg/g, total nitrogen at 0.153 mg/g, and total sugar at 0.138 mg/g. Compared to Partial Least Squares Regression and Convolutional Neural Networks, DR-CNN demonstrated superior predictive accuracy, making it a promising model for quality prediction in cigar tobacco leaves during air-curing process. Overall, VNIR-HSI based on DR-CNN can effectively predict the quality of cigar tobacco leaves at different air-curing levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The curing process is a critical stage in affecting the quality of cigar tobacco leaves, and the variations in light exposure play a major role in influencing their outcome. Light regulation has emerged as a promising method to optimize the curing process. Different types of light, such as red, blue, ultraviolet (UV), and infrared (IR), have been shown to produce varying effects on tobacco leaves, influencing factors such as pigment levels, moisture content, and nitrogen breakdown1. For example, UV light can accelerate the degradation of chlorophyll, while IR light can enhance the accumulation of certain aromatic compounds2,3,4,5. These differences in light exposure can lead to significant variations in the chemical and physical properties of the leaves, ultimately affecting their flavor, aroma, and visual quality6. Current research on light regulation offers valuable insights, but further exploration is needed to fully understand its role in the commercial curing process7.

Light factors during curing process such as intensity, wavelength, and duration can significantly affect the chemical composition and physical appearance of the leaves, making it challenging to maintain consistent quality8. These variations in light conditions can cause fluctuations in key indicators such as moisture content, chlorophyll degradation, and sugar levels, all of which directly impact the quality of the final product9. Therefore, understanding and controlling light exposure during the curing process is essential for achieving high-quality tobacco leaves.

It is crucial to ensure proper quality control during the air-curing process for maintaining the desired characteristics of cigar tobacco leaves, especially under varying light conditions. Managing the effects of light on key factors such as moisture content, nitrogen degradation, and sugar content is essential for producing leaves with uniform color, optimal sweetness, and rich aroma10. Without adequate control of light exposure, these chemical processes may be disrupted, leading to uneven leaf quality and suboptimal flavor development11. Thus, monitoring light exposure and its effects on the curing process is a critical technique for quality control12.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) provides an effective solution for monitoring the impact of light exposure on the quality of tobacco leaves13. HSI enables the rapid, non-destructive assessment of both spectral and spatial data, allowing for detailed analysis of how different light conditions influence the curing process14. HSI can capture variations in moisture, pigments, and other chemical compounds across large samples, making it a valuable tool for real-time quality control in tobacco leaf curing15.

However, high-dimensional and complex nature of hyperspectral data make challenges for traditional linear methods like Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR), which may fail to effectively capture the intricate relationships between spectral and spatial features. Deep learning models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and its variant, Diversified Region-based CNN (DR-CNN)16, showed significant potential in hyperspectral data analysis. These models are capable of extracting both local and global features from the spectral data, making them well-suited for capturing the complex, non-linear relationships often present in high-dimensional hyperspectral datasets.

The DR-CNN model, which incorporates a multi-scale feature fusion module, allows for the integration of spectral and spatial information across different scales17. This capability is particularly valuable in applications requiring high precision, such as predicting quality indicators in cigar tobacco leaves, where both spectral variability and spatial heterogeneity play critical roles.

The purpose of this study is to develop a visible and near-infrared hyperspectral imaging (VNIR-HSI) predictive model for assessing the effects of light exposure on moisture, chlorophyll, total nitrogen, and total sugar content in curing process of cigar tobacco leaves. By incorporating the DR-CNN model, it aims to enhance the predictive performance for these indicators and provide a deeper understanding of how light variation affects tobacco leaf quality at different stages of light enhanced air-curing18.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

The cigar tobacco leaves were of the CX80 variety, harvested in July 2023 from Lvshui, Laifeng County, Enshi Prefecture, Hubei Province, China (29.5090° N, 109.2160° E). Field management followed traditional local practices to ensure consistency in growing conditions. Leaves with uniform maturity were selected for harvesting. The collected leaves were subjected to two distinct curing processes: natural air-curing and modified air-curing under controlled light conditions.

For the natural air-curing process, leaves were hung in a traditional drying shed with stable temperature and humidity conditions. The temperature ranged from 25 °C to 30 °C, with humidity consistently above 80%, occasionally reaching 90%. To regulate these conditions, adjustments were made by raising the drying height and enhancing ventilation, as higher spaces in the shed generally had lower humidity and higher temperatures19.

The primary variation in the samples resulted from the second method, which involved controlled light exposure during the curing process. Freshly harvested tobacco leaves were placed under different artificial light conditions, including red (RL,680 nm), blue (BL,460 nm), green (GL,520 nm), UV (365 nm), and IR (850 nm), to examine how varying wavelengths affected moisture, chlorophyll, total nitrogen, and total sugar content. Each light condition uniquely influenced the spectral signatures of the tobacco leaves by altering moisture retention, chlorophyll degradation, and nitrogen accumulation. For instance, red light promoted sugar accumulation, while blue light supported chlorophyll breakdown, resulting in distinct spectral patterns for each treatment20. By manipulating the light exposure, the study aimed to assess the impact of these variables on the curing outcome and better understand how light conditions could optimize tobacco quality21. To adapt to these variations, the DR-CNN model was trained with spectral data grouped by light conditions, allowing the model to learn and account for these spectral differences across diverse curing environments, thus enhancing predictive accuracy and robustness.

A total of 183 samples were collected for the study, including 30 naturally cured leaves and 153 leaves subjected to modified light conditions. Leaves had four stages during air curing process, specifically at the yellowing stage (day 7), the browning stage (day 14), and the stem drying stage (day 28). The collection times and processing conditions are presented in Supplementary Table S2. After collection, hyperspectral imaging was performed on each sample, followed by further processing. Samples were divided into three parts: one for moisture content measurement, another freeze-dried for chlorophyll analysis, and the third dried for total nitrogen and total sugar content assessments.

Determination of quality indicators

Moisture content

The moisture content of the cigar tobacco leaves was measured using the gravimetric drying method22. First, the initial mass of the undried cigar tobacco leaves was accurately weighed. The leaves were placed in an oven and dried at 105 °C for a specific duration, allowing the moisture in the samples to evaporate completely. After drying, the samples were placed in a desiccator to be cool at room temperature, and their mass was recorded again. The moisture content was calculated based on the difference in mass before and after drying as following Eq.

Chlorophyll

The chlorophyll content was measured according to the method with some modifications28. An appropriate amount of tobacco leaf was placed in a 15 mL centrifuge tube, and 5 mL of 80% acetone was added. The mixture was then subjected to ultrasonic extraction for 15 min. After extraction, the mixture was centrifuged to remove solid impurities, resulting in a clear supernatant. The supernatant was transferred to a cuvette, and the absorbance at 663 nm and 645 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer (Genesys150, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). The concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll were calculated using the following formulas.

where Chl a, Chl b and Chl represent Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b and Total chlorophyll; A663 and A645 represent the absorbance of the extract at wavelengths of 663 nm and 645 nm, respectively.

Total nitrogen

The total nitrogen content in cigar tobacco leaves was determined using the Kjeldahl method23. Accurately weighed 0.5 g of tobacco leaf powder and placed it in a digestion tube. Add 10 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid and an appropriate amount of catalyst. The digestion tube was then placed in a Kjeldahl digestion unit (K-438, Büchi, Flawil, Switzerland) and heated to approximately 370 °C, digesting for 1–2 h until the solution became clear and light green or colorless. After digestion, allowed the solution to cool and added a sufficient amount of 40% sodium hydroxide solution to convert ammonium ions into ammonia gas. The ammonia gas is then distilled and captured by a standard boric acid solution. The captured ammonia reacted with the boric acid to form an ammonium ion solution, which is finally titrated with a standard solution of hydrochloric acid until a color change was observed in the indicator. The volume of acid consumed was recorded, and the total nitrogen content is calculated based on the amount of acid used during titration.

where V1 is the volume of standard acid consumed by the sample during titration (mL), V2 is the volume of standard acid consumed by the blank during titration (mL), N is the concentration of the standard acid (mol/L), W is the sample weight (g), 1.4007 is the conversion factor for nitrogen content calculation.

Sugars

The total sugar content in cigar tobacco leaves was determined using the anthrone colorimetric method14. First, 0.25 g of tobacco leaf powder was weighed and placed into a 15 mL centrifuge tube. Then, 10 mL of deionized water was added to the tube, and the mixture was extracted in a 60 °C water bath for 30 min. After extraction, the sample was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min. 1 mL of the supernatant was transferred to a new test tube, and 5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid was slowly added. 1 mL of 0.2% anthrone solution was added, and the test tube was heated in water bath at 80 °C for 10 min. After heating, the test tube was immediately placed in cold water. Once cooled, the absorbance (OD value) of the solution was measured at a wavelength of 620 nm using a spectrophotometer (Genesys150, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Finally, the absorbance value was converted into sugar concentration using a standard curve (prepared with glucose), and the total sugar content in the sample was calculated, typically expressed as a percentage (%).

VNIR-HSI data acquisition

Selected cigar tobacco leaf samples were cropped and placed in a 3-cm diameter petri dish for image acquisition. Each sample was collected three times in the middle of leaf, undamaged area avoiding the main vein. HSI was collected using a Specim FX10 DM push-broom visible-near infrared hyperspectral imaging system (Isuzu Optics, Shanghai, China). VNIR-HSI of each sample were captured in reflection mode, with a spectral range of 400–1700 nm, an exposure time of 50 ms, and a scanning speed of 20 mm/s. The system software automatically performed black and white calibration on the collected images.

Spectral extraction and preprocessing

After obtaining the hyperspectral images through acquisition and correction, further processing is required to extract the spectral information of the samples. During the acquisition process, the imaging system automatically generates Red, Green, Blue (RGB) and hyperspectral channel images in the corresponding spatial dimensions. Based on the visible range of samples observed in the RGB images, a fixed region of interest (ROI) of 50 × 50 pixels was selected from the center of each image, ensuring consistent data extraction and minimizing edge effects across samples24 .The average spectrum of a ROI was extracted as the spectral information for each sample.

No additional preprocessing techniques (e.g., normalization, smoothing) were applied to the spectral data according to the method mentioned in the study by wang et al.25. This choice was made to evaluate the DR-CNN model’s performance on raw hyperspectral information and to test its inherent robustness and adaptability to unprocessed data. While this approach provided insights into the model’s raw data handling capacity, it may have limited the predictive accuracy of the PLSR model, as preprocessing typically enhances traditional models by reducing noise and improving signal clarity. After extraction, the dataset was split into 70% training set, 15% validation set, and 15% test set.

Data analysis

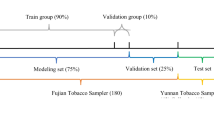

The overall data analysis workflow in this study is shown in Fig. 1, which primarily includes image segmentation, spectral extraction, feature extraction using the CNN model, and modeling and comparison. The main tasks were completed using the open-source software Python (version 3.7.0). Fig. 2

Data analysis methods

Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR)

PLSR is a linear regression method that projects both the predictors (spectral data) and the target variables onto a lower-dimensional latent space, maximizing their covariance26. This makes PLSR an attractive choice when dealing with high-dimensional spectral data, as it reduces the complexity of the data while preserving the relationships between the variables27. The optimal number of latent variables was determined through K-Fold Cross-Validation28.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

CNNs are a classic deep learning technique, specifically designed for processing image data29,30. Compared to traditional machine learning methods, CNNs can automatically extract spatial and spectral features from images, reducing the reliance on manual feature extraction. A typical CNN architecture consists of an input layer, multiple convolutional layers, pooling layers, activation layers, and fully connected layers. The convolutional layers use convolutional kernels to extract local features from the input image, while the pooling layers down sample the feature maps to reduce their size and improve computational efficiency. Activation layers (ReLU) introduce non-linearity, enabling the model to learn complex features. The fully connected layers map the extracted features to the output space. This study used the LeNet-5 architecture, which consists of three convolutional blocks and two fully connected layers31. Each convolutional block contains a convolutional layer and a pooling layer, responsible for feature extraction and reducing the size of the feature maps.

Diversified Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks (DR-CNN)

DR-CNN is a CNN model optimized for capturing spatial heterogeneity in hyperspectral images. Unlike traditional CNNs that may overlook localized spatial variations, DR-CNN’s architecture can divide each hyperspectral image into multiple ROI and applies independent convolutional operations within each region. This approach enables the model to capture localized spectral variations, addressing the spatial heterogeneity present in hyperspectral images32. By focusing on distinct areas, DR-CNN can learn region-specific features better, thereby improving predictive accuracy in areas with significant spectral variability. In addition to region-based processing, DR-CNN incorporates a multi-scale feature fusion module to capture both local and global spectral characteristics across different spatial resolutions33. This module extracts features at various scales, allowing the model to account for detailed local patterns as well as broader contextual information, enhancing its ability to process complex hyperspectral data. Following region-based feature extraction, DR-CNN employs feature fusion techniques, such as weighted summation or attention mechanisms, to integrate regional information into a comprehensive representation. By incorporating an attention mechanism, the model assigns varying importance to each region, allowing it to focus on the most relevant spectral features, thus improving predictive accuracy across diverse regions.

Strategies to prevent overfitting

To ensure the generalization of the models and prevent overfitting, particularly with small sample sizes, several strategies were employed during model training. First, K-fold cross-validation to assess model were used across different subsets of the data. The dataset was divided into K subsets, with the model being trained on K-1 subsets and validated on the remaining subset. This method helps ensure that the model generalizes well to unseen data and prevents overfitting to any single data partition.

Additionally, early stopping was applied during training to further reduce the risk of overfitting. This technique halts the training process as soon as the validation error stops improving, preventing the model from learning noise or irrelevant patterns in the training data. Early stopping allowed us to select the best-performing model based on validation performance, thereby improving its generalization capability.

Considering the relatively small sample size, data augmentation techniques were also employed, including random cropping and horizontal flipping. These augmentations expanded the diversity of the training dataset, enabling the model to learn more varied patterns and features, which in turn helped mitigate the risk of overfitting.

Furthermore, dropout regularization was applied in both CNN and DR-CNN models to improve generalization. Dropout randomly drops a fraction of the neurons during training, forcing the model to learn more robust features and reducing its dependency on any single feature or data point, thereby preventing overfitting.

Finally, to ensure the models generalized well across different data regions, three dataset selection strategies were used: (1) selecting the two groups with the highest and lowest values of the target variable to cover extreme data; (2) selecting a range of low, medium, and high values to ensure the model’s generalization capability; (3) using the entire dataset to avoid overfitting or performance degradation due to insufficient samples, though this approach incurs the highest training cost.

The use of extreme and range value sampling was intended to improve the model’s ability to generalize across diverse conditions by exposing it to both boundary and mid-range values. This approach helps the model learn from a broader range of scenarios, potentially enhancing its robustness and accuracy in real-world applications. The combination of extreme, range, and full dataset sampling ensures that the model does not become overly reliant on specific data regions, thereby supporting a more balanced learning process across the entire feature space.

Model performance evaluation

To reduce computational complexity, lightweight convolutional layers were employed in the DR-CNN model, significantly decreasing parameters and operations while retaining predictive accuracy. GPU acceleration further enhanced processing speed, enabling practical real-time predictions during tobacco curing.

The performance of models was evaluated using the correlation coefficients r(rc, rv, rp) for the training, validation, and test sets, as well as the corresponding root mean square errors (RMSEC, RMSEV, RMSEP)34. It indicates higher accuracy and stability in the model’s predictions when a correlation coefficient r2 closer to 1 and a root mean square error (RMSE) closer to 0.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the dataset

Table 1 summarizes the comparative performance of the PLSR, CNN, and DR-CNN models across different quality indicators, including moisture, chlorophyll, nitrogen, and sugar content. This table provides RMSE values for the training, validation, and test sets, as well as R² values for the test set, allowing a direct comparison of each model’s predictive accuracy. As shown in Table 1, the DR-CNN model consistently outperformed both the CNN and PLSR models, demonstrating lower RMSE values and higher R² values across all indicators.

As shown in Table S1, the statistical details of quality indicators for each dataset were divided into natural samples and five modified samples to observe the effect of light wavelengths on the air-curing process of cigar tobacco leaves. It noted that the bold rows in the table represent the total sample count for each dataset.

At all stages, the moisture content of natural samples was slightly higher than that of modified samples. This might be due to the more stable humidity conditions in natural environments, whereas light treatment could increase leaf moisture evaporation. Additionally, the applied lights accelerated the metabolism of the leaves, further affecting moisture content. The average moisture content during the yellowing stage was higher, typically between 55% and 64.5%. This might be the leaves at this stage retained a higher moisture content, and moisture evaporation had not yet at peak during the drying process. In contrast, during the browning stage, the moisture content of the leaves significantly decreased, with an average range of 33.5–42.85%, indicating that moisture had been substantially reduced. Finally, during the stem-drying stage, the moisture content further decreased, with an average dropping between 15.9% and 20.9%. Overall, it showed a gradual decline from the yellowing stage to the stem-drying stage, which aligned with the natural dehydration process during leaf drying.

Performance analysis of moisture content model

The performance of near-infrared hyperspectral models for predicting moisture content is shown in Supplementary Table S3. To support model comparison, the standard deviation (SD) and range of reference values for moisture content were analyzed, with an SD of 17.7% under natural conditions. Three dataset strategies—NC + IR, NC + RL + IR, and ALL—were compared for model generalization and fitting accuracy. The PLSR model performed well on the NC + IR dataset, but its validation (RMSEV = 4.187%) and prediction errors (RMSEP = 4.533%) were significantly higher than the training error. By adding more diverse data (NC + RL + IR), generalization improved slightly.

CNN improved generalization by handling non-linear data. With the NC + RL + IR dataset, it achieved better generalization (RMSEV = 3.421%, RMSEP = 3.603%) than PLSR. With the ALL dataset, CNN showed further improvements in generalization (RMSEP = 3.298%).DR-CNN exhibited the best performance across all datasets, particu-larly on the ALL dataset (RMSEC = 3.532%, RMSEP = 3.109%), with the highest RER.

Performance analysis of chlorophyll quantification

The chlorophyll quantification results (Supplementary Table S4) showed that PLSR performed ad-equately on simple datasets such as RL + BL but struggled with more complex datasets (RMSEP = 1.384 mg/g). With a standard deviation (SD) of 1.5 mg/g, the chlorophyll data highlights the inherent variability in this quality indicator, which posed challenges for linear models like PLSR. CNN showed significant improvement with the RL + BL + UV dataset (RMSEV = 0.692 mg/g). DR-CNN performed well with all models, particularly on the ALL dataset (RMSEC = 0.686 mg/g, RMSEP = 0.883 mg/g), with high RER values (12.36–14.44).

Performance analysis of nitrogen content

For nitrogen content prediction (Table S5), PLSR performed best on simpler datasets but struggled with generalization on the ALL dataset. The nitrogen data exhibited a standard deviation (SD) of 0.52 mg/g, indicating significant variability that posed challenges for linear models like PLSR in complex datasets. CNN improved generalization, particularly on the VL + GL + NC dataset (RMSEC = 0.149 mg/g). On the ALL dataset, DR-CNN achieved the lowest RMSEP (0.153 mg/g).

Performance analysis of sugar Content

In Table S6, the sugar content models exhibited weaker performance compared with other indicators due to the inherently low sugar content and minimal spectral change. The standard deviation (SD) for sugar content was relatively low, indicating limited variability, which constrained the models’ predictive accuracy. PLSR showed higher errors across all datasets. CNN and DR-CNN performed better, with DR-CNN offering the most accurate predictions (RMSEP = 0.138 mg/g), although all models struggled with the limited data differentiation in sugar content.

Visualization

Linear Fitting

To visualize the prediction results, the visible and near-infrared (VNIR) spectrum of cigar tobacco leaves was selected as representative data. The prediction results of the three models using the training set, validation set, and test set were plotted, as shown in Fig. 3. The models’ performance is indicated by how closely the actual values and the predicted values align along a straight line.

Prediction results by three models. (a) moisture PLSR; (b) moisture CNN; (c) moisture DR-CNN; (d) chlorophyll PLSR; (e) chlorophyll CNN; (f) chlorophyll DR-CNN; (g) nitrogen PLSR; h) nitrogen CNN; (i) nitrogen DR-CNN; (j) sugar PLSR; (k) sugar CNN; (l) sugar DR-CNN. The red line in each panel represents the linear fit of the dataset. The closer the scatter points are to the line, the better the model’s predictive accuracy and the stronger the correlation between the predicted and actual values. A tighter distribution of points around the line indicates more stable model performance with lower variance. Conversely, a wider spread of points around the fitting line suggests higher variance and less accurate predictions.

cccccccConfusion Matrix

Error distribution histograms were used to assess the accuracy of moisture content, chlorophyll content, nitrogen content, and sugar content predictions for cigar tobacco leaves. The histograms display the distribution of prediction errors, with the frequency of errors plotted against the magnitude of the error (i.e., the difference between actual and predicted values). The results are presented in Fig. 4.

Discussion

The higher moisture content observed in natural samples may be due to the more stable humidity conditions in natural environments, whereas light treatments could increase leaf moisture evaporation. The applied lights may have accelerated the metabolism of the leaves, further affecting moisture content. The higher average moisture content during the yellowing stage suggests that moisture evaporation had not yet peaked during the drying process. The gradual decline in moisture content from the yellowing stage to the stem-drying stage aligns with the natural dehydration process during leaf drying.

The RL samples showed higher chlorophyll content, suggesting that RL irradiation could enhance photosynthesis during the air-curing process, resulting in higher chlorophyll retention. Although other light treatments enable photosynthesis, they might not be as effectively absorbed by chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b as RL light20.

The nitrogen content being higher in light-treated samples may be because light accelerates the drying process of the leaves, leading to an increase in the relative concentration of nitrogen. Lights might affect nitrogen metabolism in plants, leading to nitrogen accumulation35.

The minimal differences in sugar content across different treatments indicate that sugar remains relatively stable during the drying process, especially under natural drying conditions. Carefully managed drying processes result in minor fluctuations in sugar content, leading to minimal variations between datasets36.

These findings align with previous studies demonstrating the limitations of traditional models like PLSR in handling complex, nonlinear data structures, particularly for moisture content predictions37. In contrast, CNN and DR-CNN models, with their non-linear processing capabilities, excel in capturing intricate patterns within the spectral data, resulting in enhanced predictive accuracy and generalization38.

The improved generalization of CNN and DR-CNN across multiple datasets supports the growing consensus in hyperspectral imaging research that deep learning methods are more robust for moisture prediction under varying environmental conditions39.

For chlorophyll quantification, the DR-CNN model demonstrated superior accuracy and robustness across multiple datasets, likely due to its multi-scale feature fusion capabilities, which allow it to effectively integrate spatial and spectral information. For non-linearly correlated variables, such as nitrogen content, DR-CNN outperformed traditional methods due to its enhanced ability to capture complex, non-linear patterns in hyperspectral data. This advantage is crucial for accurately predicting nitrogen content, where non-linear dependencies are common. In contrast, for linearly correlated variables like moisture, while PLSR performed adequately, DR-CNN and CNN demonstrated even higher accuracy, showcasing deep learning models’ versatility across diverse data structures. Prior studies have also reported the effectiveness of CNN-based models in chlorophyll quantification for crops, citing their ability to reduce noise and extract essential spectral features from hyperspectral images40. This is particularly relevant when dealing with datasets that have varying chlorophyll content, as CNN and DR-CNN models can capture both spectral and spatial details, leading to more accurate predictions41. PLSR models, despite their utility for linear data, face limitations in handling such nonlinear dependencies, resulting in reduced accuracy compared to CNN and DR-CNN.

Regarding nitrogen content prediction, our results indicate that DR-CNN is more capable of capturing nitrogen content variability in complex datasets compared to traditional methods. Nitrogen content prediction often faces challenges due to its indirect correlation with spectral reflectance. Deep learning models improve prediction accuracy by leveraging multi-scale feature extraction, a capability that simpler linear models such as PLSR lack42. These results reinforce the importance of using models that can handle nonlinear relationships when predicting nitrogen content43.

The relatively lower performance of the models for sugar content prediction is consistent with other studies that have reported difficulties in hyperspectral detection of sugars. Sugar content, especially in small quantities, has less direct impact on the reflectance spectra of plant tissues44. Furthermore, sugar content changes during drying are subtle and may not result in significant spectral variations45. These challenges highlight the need for further development in deep learning architectures tailored for detecting minor chemical changes46.

In the visualization of prediction results (Fig. 3), DR-CNN consistently provided the best predictions, as shown by the alignment of its scatter points along the diagonal in all cases. These results suggest that DR-CNN is more stable and precise across all four quality indicators compared to CNN and PLSR. PLSR performed worse in scenarios involving complex and nonlinear relationships, a limitation highlighted in several studies analyzing spectral data modeling47.

For moisture content, DR-CNN exhibited better fitting and less deviation, while PLSR showed a wider scatter, reflecting instability in handling high moisture variation, as observed in related moisture content prediction studies using hyperspectral imaging. Similarly, DR-CNN’s superior performance for chlorophyll content is consistent with studies where deep learning models were shown to be more effective than traditional models in pigment prediction6.

Nitrogen and sugar content predictions also highlight the advantages of DR-CNN in handling outliers and extreme values. This finding aligns with previous studies where DR-CNN showed superior generalization across multiple datasets. PLSR performed worse, particularly in the presence of nitrogen and sugar variability, confirming that linear models often struggle with complex spectral features48.

The error distribution histograms (Fig. 4) reveal that the DR-CNN model consistently outperformed the PLSR and CNN models across all four quality indicators: moisture, chlorophyll, nitrogen, and sugar content. Compared to the other models, DR-CNN demonstrated better accuracy, smaller prediction errors, and fewer outliers. These results highlight DR-CNN’s ability to handle complex, nonlinear data relationships and capture subtle spectral patterns in hyperspectral data, as supported by previous studies49,50,51.

For PLSR, the error distribution was wider, reflecting its limitations in managing nonlinear relationships and high-dimensional spectral variability. While CNN showed improved accuracy over PLSR, some challenges remained in categories with greater data complexity. The DR-CNN model’s multiscale feature fusion capability and robust handling of nitrogen and sugar content variability further validate its superiority, particularly in datasets with intricate spectral variations.

However, PLSR assumes linear relationships between the input variables (spectral features) and the target variables (quality indicators). In this study, we found that PLSR struggled to capture the non-linear and complex relationships present in the hyperspectral data, especially when predicting variables like moisture and nitrogen content. The high-dimensional, non-linear nature of hyperspectral data introduces variability that PLSR, being a linear model, cannot fully capture. This limitation is why PLSR underperformed compared to CNN and DR-CNN models, which can model complex non-linear patterns and interactions between spectral features. In contrast to PLSR, both CNN and DR-CNN leverage deep learning techniques that can capture these intricate relationships, resulting in better predictive accuracy and generalization across different datasets. Compared to traditional CNNs, DR-CNN’s region-based structure and multi-scale feature fusion provide a notable advantage in processing non-linear and region-specific spectral features. This design makes DR-CNN particularly suited for hyperspectral imaging tasks that involve complex data structures, as it effectively captures both spatial and spectral heterogeneity.

Conclusions

This study successfully applied hyperspectral imaging (HSI) technology, combined with fixed-region CNN and diversified region-based CNN (DR-CNN) models, to predict key quality indicators—moisture, chlorophyll, nitrogen, and sugar content—in cigar to-bacco leaves during different air-curing stages. The use of visual and near-infrared hyperspectral imaging (VNIR-HSI) data greatly enhanced the accuracy of these predictions, and the performance of DR-CNN was validated as the best model compared to both the traditional PLSR model and CNN.

The results demonstrated that both CNN and DR-CNN models significantly out-performed the traditional PLSR method, with DR-CNN showing the highest accuracy and generalization ability. DR-CNN’s ability to capture spatial information at multiple scales and its integration of multi-scale feature fusion enabled it to provide robust predictions for high-dimensional hyperspectral data.

However, the study was based on a relatively limited dataset, which could impact the generalizability of the model across different tobacco types or environmental conditions. To further improve the model’s applicability, future research should focus on expanding the dataset and including a broader range of samples from various curing environments. Additionally, while DR-CNN proved to be highly accurate, its computational demands may limit its use in real-time applications. The DR-CNN model, after optimizations, demonstrated strong potential for real-time application in tobacco leaf curing. The computational optimizations, including lightweight layers and GPU acceleration, significantly reduced the processing time per sample. On high-performance GPUs, the model was able to process a single tobacco leaf sample in under 2 s, making it feasible for real-time monitoring of moisture content, chlorophyll levels, and other quality indicators during the curing process. On mid-range GPUs or edge devices, such as NVIDIA GTX 1060, the processing time per sample was approximately 5–10 s.

Although DR-CNN requires more computational resources than traditional models like PLSR, the optimizations implemented in this study allow for timely predictions, which are crucial for practical applications in tobacco curing. With the use of high-performance hardware such as GPUs or edge devices, the DR-CNN model can be deployed in real-time environments where continuous monitoring and feedback are necessary to optimize the curing process.

Future studies could explore the impact of preprocessing techniques, such as noise reduction, normalization, or smoothing, to potentially enhance model performance, particularly for PLSR, in complex environments where spectral variability may affect prediction accuracy.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Fan, J. Y., Zhang, L. & Li, A. J. Study on the production key technology of handmade cigar. Anhui Nongye Kexue. 44, 104–105 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. Oxygen regulation of microbial communities and chemical compounds in cigar tobacco curing. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1425553 (2024).

Guo, X. et al. Support Tensor machines for classification of Hyperspectral Remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 54, 3248–3264 (2016).

Ejaz, I. et al. Detection of combined frost and drought stress in wheat using hyperspectral and chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Environ. Technol. Innov. 30, 103051 (2023).

Liu, L., Ngadi, M. O., Prasher, S. O. & Gariépy, C. Categorization of pork quality using Gabor filter-based hyperspectral imaging technology. J. Food Eng. 99, 284–293 (2010).

Feng, L. et al. Hyperspectral imaging for seed quality and safety inspection: a review. Plant. Methods. 15, 91 (2019).

Lazzarin, M. et al. LEDs make it resilient: effects on Plant Growth and Defense. Trends Plant. Sci. 26, 496–508 (2021).

Meng, Y. et al. Analysis of the relationship between color and natural pigments of tobacco leaves during curing. Sci. Rep. 14, 166 (2024).

Hu, W. et al. Sensory attributes, chemical and microbiological properties of cigars aged with different media. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1294667 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Microbial and enzymatic changes in cigar tobacco leaves during air-curing and fermentation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 107, 5789–5801 (2023).

Zhao, S., Wu, Z., Lai, M., Zhao, M. & Lin, B. Determination of optimum humidity for air-curing of cigar tobacco leaves during the browning period. Ind. Crops Prod. 183, 114939 (2022).

Shi, C. & Pun, C. M. Superpixel-based 3D deep neural networks for hyperspectral image classification. Pattern Recognit. 74, 600–616 (2018).

He, X., Chen, Y. & Ghamisi, P. Dual Graph Convolutional Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification with Limited Training Samples. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–18 (2022).

Morris, D. L. Quantitative determination of Carbohydrates with Dreywood’s Anthrone Reagent. Science 107, 254–255 (1948).

Zhang, C. et al. Hyperspectral imaging analysis for ripeness evaluation of strawberry with support vector machine. J. Food Eng. 179, 11–18 (2016).

Roy, S. K., Krishna, G., Dubey, S. R., Chaudhuri, B. B. & HybridSN Exploring 3D-2D CNN feature hierarchy for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 17, 277–281 (2020).

Liu, J., Fan, X., Jiang, J., Liu, R. & Luo, Z. Learning a deep Multi-scale Feature Ensemble and an edge-attention Guidance for Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 32, 105–119 (2022).

Chen, Y., Jiang, H., Li, C., Jia, X. & Ghamisi, P. Deep feature extraction and classification of hyperspectral images based on convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 54, 6232–6251 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. Analysis of the structure and metabolic function of microbial community in cigar tobacco leaves in agricultural processing stage. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1230547 (2023).

De Wit, M., Galvão, V. C. & Fankhauser, C. Light-mediated hormonal regulation of Plant Growth and Development. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 67, 513–537 (2016).

Wang, Q. & Lin, C. Mechanisms of cryptochrome-mediated photoresponses in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 71, 103–129 (2020).

C3-33AOAC Official Method 966.02Loss on Drying (Moisture) in Tobacco: Gravimetric Method. in Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL (ed. Latimer, G. W., Jr.) 0. doi:Oxford University Press, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/9780197610145.003.1367

AOAC Official Method 959.04Nitrogen in Tobacco: Kjeldahl Method for Products Containing Nitrates. in Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL (ed. Latimer, G. W., Jr.) 0. doi:Oxford University Press, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/9780197610145.003.1369

Tunny, S. S. et al. Hyperspectral imaging techniques for detection of foreign materials from fresh-cut vegetables. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 201, 112373 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. A review of deep learning used in the hyperspectral image analysis for agriculture. Artif. Intell. Rev. 54, 5205–5253 (2021).

Wold, H. Estimation of principal components and related models by iterative least squares. J. Multivar. Anal. - MA 1, (1966).

Teshome, F. T., Bayabil, H. K., Schaffer, B., Ampatzidis, Y. & Hoogenboom, G. Improving soil moisture prediction with deep learning and machine learning models. Comput. Electron. Agric. 226, 109414 (2024).

Geladi, P. & Kowalski, B. R. Partial least-squares regression: a tutorial. Anal. Chim. Acta. 185, 1–17 (1986).

Gu, J. et al. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit. 77, 354–377 (2018).

Marques, G. & Agarwal, D. De La Torre Díez, I. Automated medical diagnosis of COVID-19 through EfficientNet convolutional neural network. Appl. Soft Comput. 96, 106691 (2020).

Lecun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE. 86, 2278–2324 (1998).

Zhang, M., Li, W. & Du, Q. Diverse region-based CNN for Hyperspectral Image classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 27, 2623–2634 (2018).

Chen, L. C. et al. Semantic image segmentation with Deep Convolutional nets, atrous Convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 40, 834–848 (2018).

Francois Chollet. Deep Learning with Python, Second Edition. Manning, (2021).

Perrella, G. & Kaiserli, E. Light behind the curtain: photoregulation of nuclear architecture and chromatin dynamics in plants. New. Phytol. 212, 908–919 (2016).

Barbedo, J. G. A. A review on the combination of deep learning techniques with proximal hyperspectral images in agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 210, 107920 (2023).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM. 60, 84–90 (2017).

Wold, S., Sjöström, M. & Eriksson, L. PLS-regression: a basic tool of chemometrics. Chemom Intell. Lab. Syst. 58, 109–130 (2001).

Ghamisi, P. et al. Advances in Hyperspectral Image and Signal Processing: a comprehensive overview of the state of the art. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 5, 37–78 (2017).

Zhu, F., Qiao, X., Zhang, Y. & Jiang, J. Analysis and mitigation of illumination influences on canopy close-range hyperspectral imaging for the in situ detection of chlorophyll distribution of basil crops. Comput. Electron. Agric. 217, 108553 (2024).

Zhao, R. et al. Deep learning assisted continuous wavelet transform-based spectrogram for the detection of chlorophyll content in potato leaves. Comput. Electron. Agric. 195, 106802 (2022).

Zhang, J., Yu, J. & Tao, D. Local deep-feature alignment for unsupervised dimension reduction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 27, 2420–2432 (2018).

Raj, R., Walker, J. P., Pingale, R., Banoth, B. N. & Jagarlapudi, A. Leaf nitrogen content estimation using top-of-canopy airborne hyperspectral data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 104, 102584 (2021).

Sarić, R. et al. Applications of hyperspectral imaging in plant phenotyping. Trends Plant. Sci. 27, 301–315 (2022).

Silva, R., Freitas, O. & Melo-Pinto, P. Evaluating the generalization ability of deep learning models: an application on sugar content estimation from hyperspectral images of wine grape berries. Expert Syst. Appl. 250, 123891 (2024).

Lin, T. H. & Lin, C. H. Hyperspectral Change Detection using semi-supervised graph neural network and Convex Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–18 (2023).

Caporaso, N., Whitworth, M. B. & Fisk, I. D. Protein content prediction in single wheat kernels using hyperspectral imaging. Food Chem. 240, 32–42 (2018).

Bai, J. et al. Hyperspectral image classification based on Multibranch attention Transformer Networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–17 (2022).

Bi, J. & Zhang, C. An empirical comparison on state-of-the-art multi-class imbalance learning algorithms and a new diversified ensemble learning scheme. Knowl-based Syst. 158, 81–93 (2018).

Janela, T. & Bajorath, J. Uncovering and tackling fundamental limitations of compound potency predictions using machine learning models. Cell. Rep. Phys. Sci. 5, 101988 (2024).

Liu, B. et al. Deep multiview learning for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 59, 7758–7772 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. conceived the experiment(s), developed the methodology, and prepared the original draft. J.X. conducted the experiment(s) and provided software support. J.W., J.J., and J.Y. validated the results, while L.Z. contributed resources. Q.X. handled data curation. Z.Z. created visualizations. M.C. supervised the project, acquired funding, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.H. provided project administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Compliance Statement

The plant specimens used in this research were from the CX80 cigar tobacco variety, cultivated in compliance with institutional, national, and international guidelines. The necessary permissions for the cultivation and study of these plants were obtained from the relevant local agricultural authorities in Laifeng County, Hubei Province, China. As the CX80 variety is not a wild species and is widely cultivated, no additional permits were required under international conservation conventions.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, J., Wang, J., Jiang, J. et al. Quality prediction of air-cured cigar tobacco leaf using region-based neural networks combined with visible and near-infrared hyperspectral imaging. Sci Rep 14, 31206 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82586-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82586-2