Abstract

The purpose of this study is to identify the characteristics of vortex vein ampullae in pachychoroid-spectrum disorders. This case-control study evaluated vortex vein ampullae using Optos Silverstone, an imaging device combining ultra-widefield scanning laser fundus imaging with swept-source optical coherence tomography. Consecutive patients with pachychoroid-spectrum disorders and controls who visited Kagoshima university hospital between January 2022 and December 2023 and underwent vortex vein ampullae evaluations. We compared morphological parameters of supratemporal and infratemporal vortex vein ampullae between eyes with pachychoroid-spectrum disorders and control subjects. We included 40 patients (46 eyes) with pachychoroid-spectrum disorders, and 14 healthy controls (15 eyes). We observed no significant differences in any supratemporal vortex vein ampullae morphological parameters (P ≥ 0.487 for all comparisons). In infratemporal vortex vein ampullae, eyes with pachychoroid-spectrum disorders showed significantly larger mean luminal volume (6.9 × 106 ± 1.8 × 106 pixels vs. 4.7 × 106 ± 1.5 × 106 pixels, P < 0.001) and greater mean vessel diameter (P = 0.040) compared to controls, with no significant differences in luminal proportions (P = 0.353). After adjusting for potential confounders, the pachychoroid-spectrum disorders group still demonstrated significantly larger infratemporal vortex vein ampullae luminal volume and mean vessel diameter compared to controls (P ≤ 0.011 for both analyses). Enlargement of lumen and stroma was observed exclusively in the infratemporal vortex vein ampullae in eyes with pachychoroid-spectrum disorders. Impaired choroidal drainage alone may not fully account for the observed vortex vein ampullae alterations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pachychoroid spectrum disorders (PSDs) represent a phenotype of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the leading cause of irreversible vision loss in industrialized nations1,2,3,4,5,6,7. PSD responds differently to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapies and photodynamic therapy than does conventional AMD, suggesting its distinct pathogenesis5,7,8,9. Elucidating PSD pathogenesis is critical for facilitating the development of personalized management strategies for AMD.

A pathogenetic hypothesis termed “venous overload choroidopathy” has been proposed to explain one potential cause of PSD10,11,12,13,14. This hypothesis suggests that scleral thickening increases outflow resistance in the vortex veins, consequently inducing stasis in the choroidal venous system. Despite advances in widefield choroidal imaging, current techniques have limitations. Ultrawidefield indocyanine green angiography lacks three-dimensional visualization capabilities15,16,17, whereas widefield optical coherence tomography (OCT) can only visualize the vicinity of the vortex vein ampullae (VVA)13,14,18. These technological constraints have hindered the development of a standardized method for comprehensive VVA structure assessment. Consequently, the morphological characteristics of the VVA in eyes with PSD remain largely unknown, despite their crucial role in PSD pathogenesis19,20,21,22,23,24. Optos Silverstone (Optos, UK) has recently emerged as an innovative imaging system that integrates ultrawidefield scanning laser fundus imaging (200° field of view)-guided swept-source OCT25. The expanded field of view of this device enables OCT imaging of the fundus periphery, where the VVA are located, from a frontal perspective. Such advancements have revealed potential pathogenic mechanisms in various retinal and choroidal diseases18,19,20.

This study aims to elucidate the VVA characteristics in PSD by developing an evaluation method for the three-dimensional structure of VVA using Optos Silverstone.

Results

Patient characteristics

We included 40 patients (46 eyes) with PSD (CSC, 32 eyes [69.6%]; PPE, 9 eyes [19.6%]; PNV, 4 eyes [8.7%]; PCV, 1 eye [2.2%]) and 14 healthy controls (15 eyes). Table 1 shows the detailed patient characteristics. Compared with the healthy group, the PSD group demonstrated significantly greater CCT (P = 0.015) and a lower proportion of symmetrical Haller vessel running patterns (P = 0.010). In the PSD group vs. the healthy group, the patterns were distributed as follows: upper dominant (50.0% vs. 20.0%), lower dominant (21.7% vs. 6.7%), and symmetrical (28.3% vs. 73.3%).

Comparisons of VVA morphology between PSD eyes and healthy eyes

We observed no significant differences in the supratemporal VVA morphological parameters between PSD eyes and healthy eyes (P ≥ 0.487 for all comparisons, Table 2 and Fig. S1). For infratemporal VVA, eyes with PSD presented a significantly greater mean luminal volume (PSD vs. healthy, 6.9 × 106 ± 1.8 × 106 pixels vs. 4.7 × 106 ± 1.5 × 106 pixels, P < 0.001). The mean vessel diameter and total vessel length of Infratemporal VVA in the PSD were significantly greater in the PSD group than in the control group (P ≤ 0.021 for both comparisons). In contrast, no significant difference in the vessel luminal proportion in the infratemporal VVA region was detected between the groups (P = 0.353).

After adjusting for potential confounders, the PSD group demonstrated significantly greater infratemporal VVA luminal volume and vessel diameter than the healthy group did (P ≤ 0.011 for both comparisons, Table S1). However, no clear difference was observed in the total vessel length (P = 0.220). Comparison of VVA morphology among PSD subtypes (excluding PCV) revealed no significant differences (Table S2).

Comparisons of VVA morphology among running patterns of the Haller vessel for eyes with PSD

The upper dominant group exhibited the largest supratemporal VVA volume (P = 0.040, Table 3), whereas the lower dominant group presented the largest infratemporal VVA volume (P = 0.111). Compared with the lower dominant group, the upper dominant group presented significantly greater vertical differences in luminal volume (Steel‒Dwass test: upper dominant vs. lower dominant, P = 0.006; symmetry vs. upper dominant, P = 0.476; symmetry vs. lower dominant, P = 0.139).

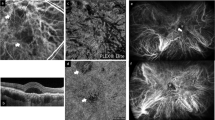

The vertical differences in the luminal proportion and mean vessel diameter demonstrated a similar trend as that for the luminal volume (Steel‒Dwass test: luminal proportion, upper dominant vs. lower dominant, P = 0.003; mean vessel diameter, upper dominant vs. lower dominant, P = 0.001). Figure 1 illustrates a representative case with VVA evaluations. Similar to the PSD group, healthy subjects with upper dominance showed greater supratemporal VVA volume (Table S3).

Vortex vein ampullae images of a patient with the upper-dominant Haller vessel pattern. (A) This ICGA image shows a 55-year-old male patient with CSC. The axial length was 24.3 mm, and the Haller vessel running pattern was the upper-dominant type. (B,C) Enlarged views of the supratemporal and infratemporal VVA in the ICGA image. (D,E) Three-dimensional structures of the VVA acquired via ultrawidefield scanning laser fundus image-guided swept-source OCT. The luminal volume was 7,578,810 pixels for the supratemporal VVA and 4,705,821 pixels for the infratemporal VVA. CSC central serous chorioretinopathy, ICGA indocyanine green angiography, VVA vortex vein ampulla, OCT optical coherence tomography.

Associations between VVA morphology and patient characteristics

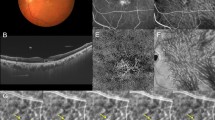

The infratemporal VVA luminal volume was significantly positively associated with CCT (β = 0.7 × 10⁴, P = 0.004) and negatively associated with age (β = -6.1 × 10⁴, P = 0.005) but was not significantly associated with axial length or sex (P ≥ 0.101 for both analyses, Fig. 2 and Table S4). The infratemporal VVA mean vessel diameter was significantly positively associated with CCT (P = 0.011) and negatively associated with axial length (P = 0.014) but was not significantly associated with age or sex (P ≥ 0.698 for both analyses). No patient characteristics were significantly associated with the supratemporal VVA luminal volume or mean vessel diameter (P ≥ 0.099 for all analyses). Sex was not significantly associated with any of the VVA morphological parameters (P ≥ 0.088 for all analyses).

Associations between the luminal volume of the VVA and patient characteristics. These scatter plots with regression lines and 95% confidence intervals illustrate the relationships between VVA parameters and patient characteristics. The luminal volume of the infratemporal VVA was positively associated with central choroidal thickness (β = 0.7 × 104, P = 0.004) and negatively associated with age (β = -6.1 × 104, P = 0.005). The associations between the luminal volume of supratemporal VVA and patient characteristics were not statistically significant (P ≤ 0.099). VVA vortex vein ampulla, S supratemporal, I infratemporal.

Discussion

This study quantitatively assessed VVA morphology in PSD patients via a developed evaluation technique. Compared with healthy eyes, PSD eyes presented significantly greater vessel luminal volume and mean vessel diameter and no significant differences in supratemporal VVA morphology. Moreover, eyes with PSD presented an enlarged VVA lumina on the dominant side of the macular Haller vessels.

Advances in OCT technology, including faster scan speeds and enhanced depth imaging, have revealed characteristic features of PSD eyes: choroidal thickening, increased choroidal lumen fraction, enlarged vascular diameter, fluid loculation, and asymmetry of the macular Haller’s vessels in the posterior pole3,26,27,28,29. Furthermore, most studies using widefield OCT have demonstrated choroidal thickening and an enlarged vascular diameter extending to the midperiphery in PSD eyes13,14,30. However, Maruko et al., utilizing OCT with the widest field of view, reported minimal differences in peripheral choroidal thickness between PSD eyes and normal eyes31. These findings suggest that venous choroidal overload and interstitial fluid retention extend from the macula toward the VVA, potentially diminishing in the peripheral VVA region13,14,30,31. In eyes with PSD, our study revealed an enlargement of both the lumen and stroma only in the inferior VVA, whereas the superior VVA remained comparable to that of control eyes. If a scleral thickening-induced increase in choroidal outflow resistance could fully explain PSD changes10,11,26, entire choroidal expansion from the VVA to the macula may potentially be observed. We cannot exclude the possibility that scleral properties limited changes in VVA morphology. However, since the sclera blocks OCT laser penetration, we think that intrascleral choroidal vessels are largely excluded from our analysis. Therefore, these findings indicate that impaired choroidal blood drainage alone cannot fully account for the pathogenesis of PSD.

Saito et al. proposed choroidal hyperperfusion as a key feature in the active phase of acute CSC32. Short posterior ciliary arteries, the choroid’s primary inflow vessels, are distributed in the posterior pole and are concentrated around the macula33,34. Choroidal hyperperfusion increases macular choroidal blood flow, elevates venous pressure and causes vascular dilation, while it may promote interstitial fluid accumulation. The selective enlargement of the lumen and interstitium in the inferior VVA region, which is absent in the superior VVA, might indicate gravitational accumulation of excessive macular fluid.

Choroidal morphology and perfusion in PSD are reportedly regionally imbalanced28,29,35. Using widefield OCT, Ishikura et al. reported that eyes with asymmetrically enlarged macular choroidal vessels also exhibited choroidal thickening near the VVA on the dominant side13. Our study demonstrated VVA enlargement on the dominant side, indicating that asymmetric vascular dilation extends beyond the macula to include the VVA. However, the etiology of this choroidal asymmetry remains elusive.

Takahashi et al. demonstrated an imbalance in perfusion zones and vortex vein systems via postscleral buckling ICGA36. Additionally, Matsumoto et al. reported predominant asymmetric choroidal vessel expansion on the ligated side in a monkey model following vortex vein occlusion37. These findings indicate that choroidal venous outflow obstruction may induce asymmetry in the choroidal vasculature. However, several observations challenge the hypothesis that choroidal asymmetry results from acquired vascular pressure loading: (1) the resolution of asymmetric vessels approximately one month postvortex vein ligation in monkey models;37 (2) a lack of an association between scleral thickness and choroidal vascular asymmetry;38 (3) the presence of choroidal asymmetry in 40–50% of normal eyes;14,29,39,40 and (4) the absence of correlation between age and choroidal asymmetry41. Considering the absence of upper VVA dilation in our study, the effect of impaired choroidal drainage on macular choroidal asymmetry may be limited.

However, while Matsumoto et al. suggest that choroidal venous anastomoses may indicate venous outflow obstruction37, these findings are also observed in normal eyes40. In addition, there is the problem that the method of evaluating choroidal venous anastomoses is subjective. Quantitative assessment of choroidal venous anastomoses, rather than their mere presence, may help clarify their role in pachychoroid-spectrum disorders in future study.

There are several limitations to this study. First, because of its retrospective nature, future longitudinal studies are needed. Second, since the sample size of this study is relatively small, comparisons among PSD subtypes by larger surveys are warranted. Third, the lack of direct measurements of choroidal blood flow restricts the ability to elucidate the relationship between VVA morphological changes and hemodynamics. However, owing to the current lack of instruments capable of measuring peripheral choroidal blood flow, morphological evaluation serves as a necessary surrogate. To mitigate potential diurnal variations in macular choroidal thickness42, which may extend to VVA, examinations were confined to 8:30 am–12:30 pm. The pixel‒to-micrometer ratio for each image is undetermined, potentially complicating comparisons between the quantitative values in this study and those derived from alternative methods. Further research is needed to elucidate the relationship between choroidal venous anastomoses and venous outflow obstruction.

In conclusion, enlargement of both the lumen and stroma was observed exclusively in the infratemporal VVA in eyes with PSD. Furthermore, asymmetry in macular choroidal morphology was observed to extend continuously to the VVA. While VVA morphology is implicated in PSD pathogenesis, impaired choroidal drainage alone may not fully account for the observed VVA alterations.

Methods

This was a single-center case‒control study. This study was conducted as a retrospective observational study. Although informed consent was waived, an opt-out opportunity was provided to patients through the hospital bulletin board and website (The Ethics Committee of Kagoshima University, Kagoshima, Japan). The Ethics Committee approved this study (No. 16012), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

Consecutive patients with PSD who visited Kagoshima University Hospital between January 2022 and December 2023 and underwent VVA evaluation by Optos Silverstone were included. We also included a healthy group consisting of participants who underwent evaluation of the VVA in the same month as the PSD patients. These control patients were diagnosed with only cataracts and had no intraocular, optic nerve, infectious, or neoplastic diseases. On the basis of previous reports, PSD was defined by the following criteria: (1) the presence of dilated Haller vessels on OCT or indocyanine green angiography (ICGA), (2) choroidal vascular hyperpermeability on ICGA, and (3) the absence of soft drusen in the macular region3,6,20,21. Among eyes fulfilling these PSD characteristics, we classified eyes as follows: pachychoroid neovasculopathy (PNV) for those with macular neovascularization (MNV) without polypoid lesions; pachychoroid polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) when MNV was accompanied by polypoid lesions; central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) in cases of serous retinal detachment without MNV; and pachychoroid pigment epitheliopathy (PPE) when only pigment epithelial detachment (PED) was present4,20,43,44,45. Diagnoses were made by two retina specialists (RF, NM) in consultation, with any disagreements resolved by a senior supervisor (HT).

Data collection

We conducted comprehensive ophthalmic examinations and multimodal imaging at the initial visit. Examinations included best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) measurement (decimal visual acuity), intraocular pressure assessment, refraction (RM8900, Topcon, Japan), axial length measurement (OA-2000, Tomey, Japan), and slit-lamp biomicroscopy. Multimodal imaging comprised spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT; Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering, Germany), optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA; PLEX Elite 9000, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Germany), fluorescein angiography (FA) and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA; Spectralis HRA and Optos California), color fundus photography (DRI OCT Triton, Topcon, Japan), and fundus autofluorescence (FAF; Spectralis HRA, Heidelberg Engineering). Furthermore, we performed VVA evaluations via ultrawidefield scanning laser fundus imaging-guided swept-source OCT (Optos Silverstone).

VVA evaluation

This study focused on evaluating the superior and inferior VVA located in the temporal quadrants of the fundus. The VVA evaluations were conducted as follows using Optos Silverstone (Fig. 3): (1) Guided by ultrawidefield scanning laser ophthalmoscope images, we performed 3–5 OCT volume scans (6 mm × 6 mm) at strategic locations encompassing and surrounding each VVA (Fig. S2). (2) We acquired a series of choroidal en-face OCT images, each representing a single-pixel depth from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) to the sclera (Supplemental video). The RPE was used as the reference boundary, and sequential en-face images were obtained at one-pixel intervals throughout the choroidal depth. To determine the choroidoscleral interface, we analyzed luminance changes along the depth axis at each measurement point. The location of steep luminance increase was identified for every point, and the deepest of these locations was designated as the overall depth. (3) We extracted luminal structures from choroidal en-face images derived from multiple OCT volume scans (Fig. S3). (4) The extracted luminal structures from multiple scans were spatially aligned using the position information recorded during image acquisition. (5) To reduce any misalignments, we implemented an automated algorithm that montaging at maximized the overlap of luminal structures across multiple scans. To mitigate the overestimation of blood vessel volume, we implemented superpixel segmentation using the simple linear iterative clustering (SLIC) method (Fig. 3)46. This process was initially applied to the layer with the largest blood vessel area and subsequently extended to all layers. For each corresponding set of superpixels across layers, we selected the one with the largest volume. (6) For vessel skeletonization, we automatically extracted the centerlines of the planar lumina. We subsequently manually corrected any skeletons that deviated significantly from the apparent lumen orientation. We then implemented an automated algorithm to adjust the centerline of the lumen structure along the depth axis. This process estimates the true center of the lumen throughout its depth, allowing us to obtain accurate skeletal information on the vessel structure. (7) On the basis of previously reported methods, we identified the center of each vortex vein ampulla (VVA)20. We then analyzed a defined region surrounding this central point to calculate and quantify VVA morphological parameters.

Process of generating a composite image of the vortex vein ampulla. Multiple en-face optical coherence tomography images acquired in the region of the vortex vein ampullae are aligned on the basis of their positional information. We modified the images to maximize the overlapping areas of the luminal structure and used the superpixel segmentation method to correct for image misalignment.

We expanded the analysis range, starting from an initial diameter of 100 pixels and incrementally increasing it by 100 pixels up to a maximum diameter of 600 pixels. For the interstitial analysis, we focused solely on the areas immediately adjacent to the vessel lumina. We analyzed the following morphological parameters: luminal volume, luminal proportion, total vessel length, and mean vessel diameter.

Statistical analysis

In this study, VVA evaluations were performed twice at different time points for 19 patients and 20 eyes (28 locations total). The reproducibility between these evaluations was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with a two-way random effects model. A single examiner performed all the examinations, while a single analyst conducted all the analyses. We selected a 400-pixel analysis range for this study based on ICC values. This range demonstrated an ICC > 0.800 for all the items, with the highest ICC for two of the four outcomes and the second highest for the remaining two (Table S5). Participant characteristics and VVA morphological parameters were compared via the Mann‒Whitney U test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. To compare the VVA morphological parameters across Haller’s vessel running patterns, we employed the Kruskal‒Wallis test, followed by post hoc Steel‒Dwass tests for statistically significant items, adjusting for multiple comparisons.

Associations between the central choroidal thickness (CCT), its related factors (age and axial length)47,48, and VVA morphological parameters were examined using linear regression analysis. Moreover, despite unknown potential confounders influencing VVA morphology, we compared the PSD and control groups via multiple linear regression, adjusting for factors associated with CCT: age, axial length, sex, and Haller vessel running patterns14,39,47,48. P value = 0.05 was set as the statistical cutoff, and we performed all analyses using R software (version 4.3.2).

Meeting presentation

This material was presented at the 39th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society for Ocular Circulation, Nara, Japan, in 2023.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the data release was not included in the research plan and was not communicated to the patients but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pascolini, D. & Mariotti, S. P. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 96, 614–618 (2012).

Wong, W. L. et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2, e106–e116 (2014).

Pang, C. E. & Freund, K. B. Pachychoroid Neovasculopathy Retina 35, 1–9 (2015).

Warrow, D. J., Hoang, Q. V. & Freund, K. B. Pachychoroid pigment epitheliopathy. Retina 33, 1659–1672 (2013).

Miyake, M. et al. Pachychoroid neovasculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Sci. Rep. 5, 16204 (2015).

Cheung, C. M. G. et al. Pachychoroid Dis. Eye 33, 14–33 (2019).

Hosoda, Y. et al. Deep phenotype unsupervised machine learning revealed the significance of pachychoroid features in etiology and visual prognosis of age-related macular degeneration. Sci. Rep. 10, 18423 (2020).

Hata, M. et al. Efficacy of intravitreal injection of aflibercept in neovascular age-related macular degeneration with or without choroidal vascular hyperpermeability. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 7874–7880 (2014).

Hata, M. et al. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy for Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy Associated with and without Pachychoroid Phenotypes. Ophthalmol. Retina. 3, 1016–1025 (2019).

Spaide, R. F. et al. Venous overload choroidopathy: a hypothetical framework for central serous chorioretinopathy and allied disorders. Prog Retin Eye Res. 86, 100973 (2022).

Imanaga, N. et al. Scleral thickness in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol. Retina. 5, 285–291 (2021).

Imanaga, N. et al. Relationship between Scleral Thickness and Choroidal structure in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 64, 16 (2023).

Ishikura, M. et al. Widefield Choroidal thickness of eyes with Central Serous Chorioretinopathy examined by swept-source OCT. Ophthalmol. Retina. 6, 949–956 (2022).

Funatsu, R. et al. Choroidal morphologic features in central serous chorioretinopathy using ultra-widefield optical coherence tomography. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 261, 971–979 (2023).

Lee, A., Ra, H. & Baek, J. Choroidal vascular densities of macular disease on ultra-widefield indocyanine green angiography. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 258, 1921–1929 (2020).

Ryu, G., Moon, C., van Hemert, J. & Sagong, M. Quantitative analysis of choroidal vasculature in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy using ultra-widefield indocyanine green angiography. Sci. Rep. 10, 18272 (2020).

Pang, C. E., Shah, V. P., Sarraf, D. & Freund, K. B. Ultra-widefield imaging with autofluorescence and indocyanine green angiography in central serous chorioretinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 158, 362–371e2 (2014).

Zeng, Q., Yao, Y., Tu, S. & Zhao, M. Quantitative analysis of choroidal vasculature in central serous chorioretinopathy using ultra-widefield swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. Sci. Rep. 12, 18427 (2022).

Matsumoto, H. et al. Pulsation of anastomotic vortex veins in pachychoroid spectrum diseases. Sci. Rep. 11, 14942 (2021).

Funatsu, R. et al. Vortex veins in eyes with Pachychoroid Spectrum disorders evaluated by the Adjusted Reverse 3-Dimensional Projection Model. Ophthalmol. Sci. 3, 100320 (2023).

Matsumoto, H. et al. Quantitative measures of vortex veins in the posterior Pole in eyes with pachychoroid spectrum diseases. Sci. Rep. 10, 19505 (2020).

Kishi, S. et al. Geographic filling delay of the choriocapillaris in the region of dilated asymmetric vortex veins in central serous chorioretinopathy. PLoS One. 13, e0206646 (2018).

Kogo, T. et al. Pigment epithelial detachment and leak point locations in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 261, 19–27 (2024).

Hayreh, S. S. & Baines, J. A. Occlusion of the vortex veins. An experimental study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 57, 217–238 (1973).

Sodhi, S. K., Golding, J., Trimboli, C. & Choudhry, N. Feasibility of peripheral OCT imaging using a novel integrated SLO ultra-widefield imaging swept-source OCT device. Int. Ophthalmol. 41, 2805–2815 (2021).

Imanaga, N. et al. Clinical factors related to Loculation of Fluid in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 235, 197–203 (2022).

Sonoda, S. et al. Structural changes of inner and outer choroid in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy determined by Optical Coherence Tomography. PLoS One. 11, e0157190 (2016).

Shiihara, H. et al. Quantitative analyses of diameter and running pattern of choroidal vessels in central serous chorioretinopathy by en face images. Sci. Rep. 10, 9591 (2020).

Hiroe, T. & Kishi, S. Dilatation of Asymmetric Vortex Vein in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol. Retina. 2, 152–161 (2018).

Xiao, B., Yan, M., Song, Y. P., Ye, Y. & Huang, Z. Quantitative assessment of choroidal parameters and retinal thickness in central serous chorioretinopathy using ultra-widefield swept-source optical coherence tomography: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 24, 176 (2024).

Maruko, I., Maruko, R., Kawano, T. & Iida, T. Comparisons of choroidal thickness and volume in eyes with central serous chorioretinopathy to that of control eyes determined by ultra-widefield optical coherence tomography. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-024-06409-w (2024).

Saito, M., Noda, K., Saito, W. & Ishida, S. Relationship between choroidal blood flow velocity and choroidal thickness in patients with regression of acute central serous chorioretinopathy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 256, 227–229 (2018).

Lejoyeux, R. et al. En-face analysis of short posterior ciliary arteries crossing the sclera to choroid using wide-field swept-source optical coherence tomography. Sci. Rep. 11, 8732 (2021).

Hayreh, S. S. Segmental nature of the choroidal vasculature. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 59, 631–648 (1975).

Bacci, T., Oh, D. J., Singer, M., Sadda, S. & Freund, K. B. Ultra-widefield Indocyanine Green Angiography reveals patterns of choroidal venous insufficiency influencing Pachychoroid Disease. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 63, 17 (2022).

Takahashi, K. & Kishi, S. Remodeling of choroidal venous drainage after vortex vein occlusion following scleral buckling for retinal detachment. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 129, 191–198 (2000).

Matsumoto, H. et al. Vortex vein congestion in the monkey eye: a possible animal model of pachychoroid. PLoS One. 17, e0274137 (2022).

Terao, N. et al. Short axial length is related to asymmetric vortex veins in central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol. Sci. 1, 100071 (2021).

Funatsu, R. et al. Normal peripheral choroidal thickness measured by widefield optical coherence tomography. Retina 43, 490–497 (2023).

Hoshino, J. et al. Variation of vortex veins at the horizontal watershed in normal eyes. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 259, 2175–2180 (2021).

Shiihara, H. et al. Quantification of vessels of Haller’s layer based on en-face optical coherence tomography images. Retina 41, 2148–2156 (2021).

Kinoshita, T. et al. Diurnal variations in luminal and stromal areas of choroid in normal eyes. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101, 360–364 (2017).

Funatsu, R. et al. A photodynamic therapy index for Central Serous Chorioretinopathy to Predict Visual Prognosis using pretreatment factors. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 253, 86–95 (2023).

van Dijk, E. H. C. et al. Half-dose photodynamic therapy versus high-density Subthreshold Micropulse Laser treatment in patients with Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: the place Trial. Ophthalmology 125, 1547–1555 (2018).

Gomi, F. et al. Initial versus delayed photodynamic therapy in combination with ranibizumab for treatment of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: the Fujisan study. Retina 35, 1569–1576 (2015).

Achanta, R. et al. SLIC superpixels compared to state-of-the-art Superpixel methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 34, 2274–2282 (2012).

Wei, W. B. et al. Subfoveal choroidal thickness: the Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology 120, 175–180 (2013).

Mori, Y. et al. Distribution of Choroidal Thickness and Choroidal Vessel Dilation in healthy Japanese individuals: the Nagahama Study. Ophthalmol. Sci. 1, 100033 (2021).

Acknowledgements

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used Claude 3.5 Sonnet for English proofreading. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers 24KJ1842 & 24K12746.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author’s contributions: RF, HT, SS, MH, YT, HS TS: Conceptualization; RF, NM, HS: Data curation; RF, HT, SS, MH, TS: Writing-Original draft preparation; RF, NM, SS, MH, YT: Visualization, Investigation. HT, SS, HS, YT, TS: Supervision; RF, HT, SS, NM, HS, MH, YT, TS: Writing-Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Mariko Hirokawa & Yasushi Tanabe are employees of Nikon Corporation. The other authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 9

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Funatsu, R., Terasaki, H., Sonoda, S. et al. Structural changes in vortex vein ampullae in eyes with pachychoroid-spectrum disorder. Sci Rep 15, 11125 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82731-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82731-x