Abstract

Food insecurity impacts 2.3 billion individuals worldwide, with the Asia–Pacific region representing more than 50% of the global undernourished population. In Pakistan, approximately 37% of the population experiences food insecurity, with rural Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) exhibiting concerning rates of stunting, wasting, and overweight individuals. This research examines the correlation between food insecurity, household factors, agricultural practices, and climate change in rural AJK. Data were collected from 470 respondents via a self-administered questionnaire utilizing convenience sampling, and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was applied for analysis. Household size, gender, income, education, and climate change influence food insecurity significantly. An increase of one person in household size is associated with a 0.499-unit rise in food insecurity, whereas a one-unit increase in income results in a 0.582-unit reduction. Females exhibit greater levels of food insecurity compared to males, while educational attainment is associated with a reduction in food insecurity. Furthermore, the implementation of sustainable agricultural practices mitigates food insecurity, whereas climate change intensifies it. The findings highlight the necessity for targeted interventions that address the specific challenges faced by rural AJK, particularly about climate-resilient agricultural practices and sustainable livelihoods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the contemporary landscape, food insecurity emerges as a silent tempest shaping the fate of a malnourished global populace, presenting an indispensable challenge that impedes both individual prosperity and communal well-being. The pursuit of universal food security becomes imperative for fostering global prosperity. As delineated by the 1996 World Food Summit, food security encompasses the continuous accessibility of adequate food, coupled with the physical and financial capacity to fulfill nutritional requirements throughout the lifespan1. This multidimensional concept encapsulates four primary facets availability, access, utilization, and stability of food resources2. Over the years, food security has ascended as a preeminent global concern, reflecting the imperative to ensure equitable access to nourishment for all.

Directly intertwined with several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), food insecurity resonates as a pivotal issue requiring urgent attention. SDG 2, “Zero Hunger,” occupies a central position, highlighting the imperative to eradicate hunger, enhance food security, and promote sustainable agriculture. Beyond addressing hunger, SDGs 1 (No Poverty) and 10 (Reduced Inequalities) underscore the intricate nexus between economic disparities and access to nutritious sustenance. Moreover, the profound impact of food insecurity on health aligns with SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being). Holistically addressing these interconnected goals underscores the global need to alleviate food insecurity3.

Statistics elucidate the magnitude of the global food security challenge, with approximately 9.2% of the global population grappling with chronic hunger, marking a concerning increase from 7.9% in 2019. Estimates project that between 691 and 783 million individuals suffered from hunger worldwide in 2022, representing a surge of 122 million compared to 2019. Furthermore, it is forecasted that 238 million people, constituting 21% of the population across 48 countries, will confront severe acute food insecurity in 20234. These statistics paint a stark picture of the severity of the global food security crisis, underlining its persistent and escalating nature across continents and regions.

Asia, with a population exceeding 4.7 billion, harbors the largest share of the global hunger-stricken populace, accounting for approximately 60% of the world’s inhabitants. In 2021, Asia accommodated over 425 million individuals experiencing undernourishment, equating to roughly 9% of the region’s total population5,6. Regrettably, the onset of the pandemic in 2020 exacerbated this situation, resulting in an additional 58 million Asians facing hunger. This dire scenario further deteriorated in 2021, with an additional 26 million individuals succumbing to hunger7. The persistence of these trends underscores the urgent need for comprehensive solutions to tackle entrenched food security challenges.

Pakistan, as the fifth most populous country globally, grapples with significant food security challenges. Despite constitutional mandates for food provision (Article 38-D), food insecurity remains a pressing concern, reflected in Pakistan’s 102nd ranking out of 125 countries in the 2022 Global Hunger Index. Approximately 36.9% of the population is affected by food insecurity, with vulnerable groups such as women bearing the brunt8,9. The country grapples with the second-highest malnutrition rate, with significant proportions of children experiencing acute malnutrition and underweight conditions. Undernourishment, infant mortality, and stunted growth further compound the multifaceted challenges of food insecurity. Various factors, including historical conflicts, agricultural constraints, and socioeconomic issues, contribute to Pakistan’s complex food security landscape, necessitating a nuanced understanding of regional and household dynamics10,11.

Climate change exacerbates Pakistan’s food security challenges, intensifying extreme weather events, natural disasters, and environmental fluctuations such as droughts and floods. Pre-existing food inflation and financial instability, compounded by recent floods, strain households’ purchasing power, impeding access to necessities like food. Furthermore, economic vulnerabilities, trade deficits, and insufficient foreign reserves hinder food and energy imports, exacerbating food insecurity nationwide. The interplay of these factors underscores the imperative for multifaceted interventions to mitigate Pakistan’s entrenched food security crisis12.

Within Pakistan, Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) stands as a vital region grappling with significant food security challenges. With a predominantly rural population, AJK faces issues such as wheat and flour shortages, projected deficits in rice, meat, and milk production, and declining vegetable yields. The region’s economy heavily relies on non-technical workers abroad, exacerbating food insecurity amidst alarming health statistics. Climate change exacerbates agricultural vulnerabilities in AJK, impacting small-scale farmers and livestock production. The challenges are made worse by rapid socioeconomic changes and variations in the environment, including the interruptions of climate change. Specifically, in the moist mountainous areas of Pakistan, covering Azad Kashmir and some regions of KPK, flash floods are occurring more frequently due to climate change attributed to an upsurge in heavy rainfall events13. Still, Pakistan is facing significant challenges due to heavy monsoon rains and flash floods, resembling a situation experienced in the past14. Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) is mostly a mountainous region, contributing to the broader context of challenges regarding the availability of food in mountainous regions. Agriculture, the backbone of Azad Jammu and Kashmir’s (AJK) economy, is under siege from climate change, imperiling the livelihoods of two-thirds of the population who rely on farming and livestock. With 13% of state land (166,432 hectares) under cultivation, predominantly rain-fed (92%), and focused on maize, wheat, and rice, the sector is highly vulnerable to climate variability. A staggering 30% reduction in water availability and quality, unpredictable rainfall patterns, and rising temperatures threaten crop yields, food security, and economic stability15. Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) is currently experiencing widespread unrest as people protest the shortage of wheat and subsidized flour16. AJK’s current wheat supply shortage of 0.194 metric tons is expected to rise to 0.939 metric tons by 2025. Currently, AJK experiences a shortage of vegetables and fruits, and the gap is likely to last till 203017 as Vegetables face a deficit of 0.240 metric tons. Almost one-third of the population, or 29%, grapples with undernourishment, surpassing the national average of 19.9%. Additionally, over half of AJK residents, specifically 57.1%, contend with food insecurity. Among them, 25.9% experience mild to severe insecurity, and 5.7% experience severe food insecurity. Although this is marginally below the less than the 58% national average, it still stands significantly higher than the least affected region, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), with a rate of 31.5%. Nationally, 60% of individuals confront food insecurity18. Shifting the focus to nutrition, the Voluntary National Review Report highlights that 39 percent of AJK’s children under five years of age are stunted, 14 percent of those under five are underweight and 4 percent are wasted19. Moreover, the infant mortality rate of 47 live births for every 1000, and 104 deaths per 100,000 live births is the maternal mortality ratio which highlights a clear link to food security19.

Global food insecurity trends have regional manifestations, particularly in vulnerable areas like Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), where 57.1% of the population is affected and 29% struggle with undernourishment19. Approximately 90% of households in AJK’s mountainous areas face food insecurity20, with alarming health consequences: an infant mortality rate of 47 per 1000 live births, a maternal mortality ratio of 104 deaths per 100,000 live births19, and 39% of children under five suffering from stunted growth.

In conclusion, the intricate landscape of food insecurity necessitates a multifaceted approach encompassing regional, national, and household-level interventions. Addressing the myriad determinants of food insecurity, from climate change impacts to socioeconomic disparities, is imperative to ensure equitable access to nourishment for all. By fostering a deeper understanding of these complex dynamics, policymakers and stakeholders can formulate targeted strategies to alleviate food insecurity and promote sustainable development globally.

The persistent issue of food insecurity in Azad Kashmir presents a significant obstacle to the region’s development, exacerbated by its unique geography and socio-economic factors. The dependence on external food resources unveils vulnerabilities deeply entrenched in historical agricultural challenges, forming just one facet of a multifaceted landscape contributing to food insecurity. With an alarming 57.1% of the population affected and 29% struggling with undernourishment, coupled with constraints like limited arable land and disrupted agricultural cycles due to climate change, the health consequences are dire, including high infant and maternal mortality rates and significant rates of stunting, underweight, and wasting in children under five. An astonishing 83% of individuals frequently experience nighttime hunger, yet food shortages persist. Local communities have stepped in to provide vital support, mitigating food insecurity through collective efforts20. These challenges demand a comprehensive investigation into the underlying factors driving food insecurity in Azad Kashmir and the formulation of effective strategies to ensure sustainable food security for the region’s population. Therefore, this study aims to explore the dynamics of food insecurity, analyzing the impact of household factors, agricultural practices, and climate change, to identify key leverage points for interventions and improve food security in rural Azad Jammu and Kashmir.

Review of literature

The role of agricultural factors in food security

Food security is intricately linked to agricultural productivity, and various factors contribute to its enhancement. Research has shown that expanding farm size and increasing farm income and non-farm income are effective drivers for improving food security21,22. This emphasis on income diversification is crucial, as it enables farmers to mitigate risks and invest in sustainable agricultural practices. Moreover, the adoption of technology in agriculture also boosts food security by increasing productivity23. Building on this, access to credit and livestock ownership further enhances food security through diversified income sources and empowerment. Furthermore, studies have highlighted the importance of factors such as off-farm/non-farm income, livestock ownership, cultivated land, fertilizer use, soil and water conservation, and oxen in contributing to greater food security24. Notably, the proximity to input markets also plays a significant role, with distance negatively affecting household food security25. Conversely, factors like off-farm income, oxen ownership, farmland size, and livestock ownership have a positive impact.

Household-level determinants of food security

Household-level factors play a significant role in shaping food security outcomes. Research has consistently shown that demographic characteristics, such as family size, dependency ratio, age, marital status, and gender, impact food security26. This underscores the importance of considering household dynamics when designing food security interventions. Education and age have also been found to positively influence food security, while larger families face challenges in maintaining food sufficiency27. Moreover, studies have identified factors such as non-farm income, access to loans and extension services, and asset ownership as positive contributors to food security28,29. However, factors like low income, limited landholdings, conflicts, and geographical remoteness reduce food security30. These findings highlight the need for targeted policies addressing the complex interplay between household-level factors.

Socio-economic factors influencing food security

Socio-economic factors, including poverty, inequality, and access to markets, also impact food security. Limited assets, socio-cultural factors, and restricted market access exacerbate food insecurity31. This is particularly evident in rural areas, where seasonal food insecurity and limited dietary variety are prevalent issues32.

Research has also highlighted the importance of income, education, and gender in shaping food security perceptions33. Furthermore, male farmers, especially in urban households, have a higher propensity for food security, which increases with larger households and family labor34. These findings underscore the need for nuanced policies addressing the intersections between socio-economic factors.

The impact of climate change on food security

Climate change poses significant threats to food security, particularly in vulnerable regions. Rising temperatures harm agriculture, reducing crop yields and damaging crops35. This, in turn, exacerbates food insecurity, especially in areas with limited adaptive capacity. Climate change will intensify rising food prices, significantly impacting food production and prices in South Asia36. Climate change is found to have a detrimental impact on food security status in Nigeria, contributing to persistent armed disputes involving natural resources and harming the nation’s human security37. Similarly, Abbas8 also indicated a noteworthy long-term negative impact of increasing temperature on selected crop production, while the short-term impact is insignificant. Research has also highlighted the impact of climate change on livestock, with extreme events like heat waves, droughts, and floods impacting grazing and animal health38. Rainfall is crucial for food security in Africa, with varying impacts among countries39. Moreover, climate change is also expected to severely impact Pakistan’s economy, with estimated losses of $19.5 billion in wheat and rice production by 205020. This will lead to increased food prices and reduced household spending, resulting in a significant contraction in Pakistan’s GDP. Ultimately, this will undermine Pakistan’s food security, threatening the livelihoods of millions and exacerbating hunger and malnutrition.

Methodology

This section provides the methodology for the examination of contributing factors of food insecurity in rural AJK. It includes theoretical background, area of study, conceptual framework, description of variables, and proposed methodology. Moreover, this chapter also offers a comprehensive approach to understanding the examination process of multilayered contributors to regions’ food security.

Area of study

The area of study for current research is the district Poonch of Azad Kashmir. Poonch District in AJK, with a population of over 0.5 million and an area of 855 km2, is a significant region bordered by several districts in AJK and Punjab. It has a unique geography and culture, with four tehsils and 122 villages. However, the district faces food insecurity challenges due to various factors, including a lack of industrial growth and reliance on daily labor and overseas employment. Alarmingly, 22.1% of children in Poonch are stunted, 2.4% of the population is overweight, and 4.8% are wasted, with severe wasting at 1.6%, the highest in AJK. These statistics highlight the need for tailored solutions to address food security and contribute to a healthier community in Poonch. Figure 1 indicates the study area.

Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework for food insecurity presented in Fig. 2 is delineated across household factors, climate change, and agricultural practices. Climate change causes crop failure, reduced yields, and food insecurity through drought, water scarcity, floods, heat stress, and weather uncertainty, making it hard for farmers/households to plan and prepare. Agricultural practices like crop failure and land degradation reduce food availability, exacerbating food insecurity. Outdated farming methods and inadequate resources worsen the problem, leading to food shortages and malnutrition. These factors increase the risk of food insecurity, particularly for vulnerable populations. Failure of agricultural practices to adapt worsens the issue. The household scale further includes demographic details such as age, gender, education, income, family size, marital status, and remittances. This comprehensive framework underscores the multi-dimensional nature of food insecurity, integrating diverse elements from macro to micro levels.

Description of variables

Dependent variable the food insecurity experience scale (FIES)

We have used the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) as our dependent variable for the study. The FIES was designed by the FAO as part of the Voices of the Hungry (VoH) project. It is a compact and standardized tool for assessing food insecurity in a variety of circumstances. The FIES was created by adapting the ELCSA’s (Latin American and Caribbean Household Food Security Measurement Scale) adult-oriented questions resulting in a concise and standardized experiential measurement appropriate for various sociocultural settings40. The FIES is based on a set of eight core questions that cover various aspects of food insecurity, these questions are:

-

1.

Were you ever frightened that you wouldn’t be able to eat enough food?

-

2.

Did you have trouble eating nutritious and healthy meals?

-

3.

Did you have to skip a meal?

-

4.

Were you restricted to just a limited type of edibles/food?

-

5.

Did you eat less than you thought?

-

6.

Did you get hungry but have nothing to eat?

-

7.

Did your family run out of food at home?

-

8.

Have you ever gone without eating for an entire day?

The Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) has been widely employed in previous studies to examine various aspects of food insecurity, making it an ideal choice for this research. For instance, Dasgupta and Elizabeth41 utilized FIES to investigate the impact of climate change on food security, while Antriyandarti et al.42 applied it to explore the role of women in food security and agriculture in the context of climate change. Similarly, Gebre and Dil43 employed FIES to analyze the links between household food insecurity and climate vulnerability in East Africa.

Independent variables

The list of independent variables and their description is presented below.

Age

Age is a continuous variable measuring the respondent’s or household head’s age in years, which may impact food security status. Different age groups face distinct challenges in accessing nutritious food, such as limited mobility, reduced social support, and financial constraints. Age was recorded in whole years, with respondents reporting their age at the time of the survey.

Hypothesis 1 Age (of the head of household) has a positive impact on the food insecurity status of the household.

Household size

Household size, the number of individuals in a household, impacts food security. Larger households may struggle to access enough food, while smaller households have limited resources.

Hypothesis 2 Household size has a favorable impact on the food insecurity status of the household.

Gender

Gender, a social and cultural variable, impacts food security, resource access, and social support. Gender roles and expectations influence food preparation, consumption, and decision-making within households.

Hypothesis 3 Female respondents experience higher levels of food insecurity compared to male respondents, due to gender-based social and economic disparities.

Marital status

Marital Status, categorized as married or unmarried, affects food security, resource access, and social support. Married individuals may share resources and support, while unmarried individuals face unique challenges in accessing food and resources.

Hypothesis 4 Unmarried respondents experience lower levels of food insecurity compared to married respondents.

Education

Education, measured by years of formal education, impacts access to information, economic opportunities, and food security. More years of education can provide individuals with knowledge, skills, and resources to improve their food security.

Hypothesis 5 Education has a negative impact on a household’s food insecurity status.

Monthly income

Household Income (in PKR) measures the total monthly income in Pakistani Rupees. Income is a crucial economic factor that affects food insecurity, resource access, and food purchasing power. Higher incomes provide greater financial resources to access nutritious food and improve food security.

Hypothesis 6 Income has a negative relation to the food insecurity status of the household.

Remittances

Remittances is a binary variable indicating whether a household receives money from outside the household (Yes or No). Remittances can be a vital income source, impacting food security, resource access, and poverty reduction. Receiving remittances can provide households with more financial resources to buy food and improve food security.

Hypothesis 7 Remittances have a negative connection with a household’s food insecurity status.

Agricultural practices

Agricultural practices is a composite variable measuring the respondent’s views on how farming practices affect food security, nutrition, yields, and crop quality. This variable combines four questions assessing the impact of agriculture/gardening, crop diversity, yield/quality changes, and control over crop quality on food security, capturing the respondent’s perceptions of these practices.

Hypothesis 8 Respondents who agree that agricultural practices (engaging in agriculture or gardening, crop diversity, and control over crop quality) positively influence food security will experience lower levels of food insecurity compared to those who disagree or are neutral.

Climate change

Climate change is a composite variable measuring the respondent’s views on how climate change affects food security, local weather, food production, and food insecurity. It combines four questions assessing the impact of climate change on these areas, capturing the respondent’s perceptions of its effects on food security.

Hypothesis 9 Respondents who agree that climate change has impacted food security (through changes in local weather patterns, food production, and food insecurity) will experience higher levels of food insecurity compared to those who disagree or are neutral.

Empirical methodology

Data

The research hypothesis is tested using questionnaire survey data collected from 470 residents of Poonch District in Azad Kashmir. The primary data was gathered using a convenient sampling technique to select a representative sample from the rural population of Poonch District, which is the third most populous district in the AJK region after Kotli and Muzaffarabad. The actual sample size of 470 respondents provides a reliable representation of the district’s population. The sample size was calculated using a formula, which determined that a sample size of 384 was required for District Poonch, which has a population of over 500,000.

The sample size calculation formula is used to determine the required sample size (S) based on the desired confidence level (Z), population proportion (P, often 50%), and error margin (M). This method ensures a rigorous and statistically sound approach to determining sample size, contributing to the reliability and validity of research findings.

Questionnaire

A self-administered questionnaire was used for data collection, consisting of seven sections. Section 1 gathered general information about respondents and interviewers. Section 2 collected demographic and household data. Section 3 assessed food insecurity using the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) and government assistance program questions. Section 4 explored household factors, Section 5 examined agricultural practices, and Section 6 addressed climate change. Finally, Section 7 focused on personal satisfaction. This comprehensive questionnaire ensured a thorough data collection process.

Proposed estimation technique

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is a statistical method that examines relationships between latent and observable variables, incorporating multiple indicators to quantify each latent variable. SMART PLS, an SEM technique, estimates complex relationships by decomposing data variance into structural and measurement models. The algorithm iteratively updates weights, loadings, and latent variable scores until convergence, providing a robust representation of relationships. This study employed SEM to analyze associations among variables, leveraging its ability to model complex relationships and explore nuanced interplay between variables.

Structural model (inner model)

In SMART PLS, the inner model represents the relationships between latent variables, which are unobserved constructs underlying observed variables. The inner model is a structural equation model describing how latent variables interact, including the direction and strength of relationships. Path coefficients, estimated using observed data and outer model weights and loadings, represent the direct effects of one latent variable on another, enabling hypothesis testing and predictions about new data.

The equation for the inner model is as below:

The equation (\(A_{j}\) = \(\sum \beta_{ji} X_{i} + \delta_{jb} Z_{b} + \epsilon_{j}\)) is a linear regression model that predicts the dependent variable \(A_{j}\). The equation includes:

Summation term \(\sum \beta_{ji} X_{i}\) represents the linear combination of independent variables \(X_{i }\) each with its coefficient \(\beta_{ji}\), showing how much each independent variable influence \(A_{j}\).

Interaction term \(\delta_{jb} Z_{b}\) is an interaction or group-level term that captures how a grouping factor \(Z_{b}\) (like different categories or clusters) affects \(A_{j}\). \(\delta_{jb}\) is the coefficient for this grouping factor.

Error term \(\epsilon_{j}\) is the error term, representing the unexplained variation in \(A_{j}\) not accounted for by the independent variables or interaction terms.

Measurement model (outer model)

The measurement model, represented by the outer model, describes how observed variables relate to latent constructs. Outer weights and loadings, estimated from observed data, reveal the importance and strength of relationships between observed variables and latent variables. The outer model estimates latent variable scores, used in the inner model to examine relationships between latent variables.

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics

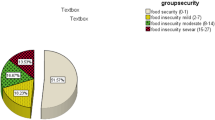

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the demographic characteristics of the study participants. The respondents exhibit a varied age distribution: 2.3% are under 25 years old, 48.5% are between 25 and 40 years old, 37.9% are aged 41 to 55 years, and 11.3% are over 55 years old. The gender distribution indicates that 63.4% of participants identify as male, while 36.6% identify as female. The data on marital status indicates that a substantial majority (96.2%) of respondents are married, whereas a minor proportion (3.8%) are single. The distribution of household sizes reveals a significant tendency towards medium-sized homes, with 58.3% consisting of 5–7 individuals. Households with 1–4 individuals comprise 31.9% of the total, whereas households with 8–10 members and those with over 10 members are less common, accounting for 8.9% and 0.9%, respectively. Household size is a significant factor contributing to food insecurity. As household size expands, the difficulty of ensuring sufficient nutrition escalates. In rural areas, where resources are limited, large families, consisting of 7 to 8 members, encounter significant challenges in fulfilling their dietary requirements. Increased household size results in challenges in resource allocation, which compromises both the quality and quantity of food available. In contrast, smaller households consisting of 3 to 4 members can more efficiently meet dietary requirements at a reduced cost.

The data regarding educational attainment among household heads reveals that a significant majority (82.1%) have not attained matriculation. Within this category, 55.3% have attained only primary education, whereas 26.8% have reached the middle or matric level of education. A mere 6% have attained an intermediate level of education, whereas 11.9% hold university degrees. The level of education significantly influences food insecurity. Lower educational attainment is frequently associated with restricted job opportunities, diminished earning potential, and insufficient knowledge regarding proper nutrition. This creates a cycle of food insecurity, as households lack the financial resources and knowledge to make informed dietary choices. Income level serves as a critical predictor of food insecurity. Higher-income households are more capable of affording nutritious food, whereas lower-income households face challenges in meeting basic needs. The financial burden intensifies in large households, as the expense of supplying balanced meals for several family members becomes excessively high.

The income distribution within the economy is varied, with 46.8% of households classified as middle-income, earning between 30,001 and 45,000 PKR. Approximately 26.4% of households possess moderately higher earnings, categorized within the range of 45,001–60,000 PKR. In contrast, 16.2% of households are classified as lower income, with earnings below 30,000 PKR. About 10.7% of households are classified as higher income, defined as those earning above 60,000 PKR. This indicates a degree of economic diversity among the participants. The demographic data indicates a direct correlation between income levels and food insecurity. Lower-income households are more susceptible to food insecurity because of constrained financial resources to satisfy essential needs. In the study, 16.2% of respondents reported monthly earnings below 30,000 PKR, while 46.8% earned between 30,001 and 45,000 PKR. The income brackets identified encompass most respondents, indicating that these income levels may be inadequate to meet increasing food prices, particularly in households with larger family sizes or additional financial responsibilities. Lower income limits access to a variety of nutritious foods, leading households to opt for cheaper, less nutritious alternatives, thereby heightening their risk of food insecurity. Moreover, only 1.1% of respondents earn above 75,000 PKR, indicating that a minimal segment of the population possesses the financial stability necessary to mitigate food insecurity. The findings indicate that food insecurity is likely more prevalent among households with incomes under 45,000 PKR, as these households face greater challenges in fulfilling their food and nutrition requirements relative to those with higher incomes.

Empirical results

Measurement model

The primary objective of this study was to create a complete, psychologically integrated model for determining the factors that affect food insecurity in the study area. This section covers the quantitative data acquired from a survey, which was then evaluated using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) with SMART PLS software. The investigation encompassed the quantification of the model using Confirmatory Factor investigation (CFA) and the structural model utilizing the bootstrapping technique. The CFA was employed to study the construct validity of the model. The internal consistency of the instrument was established, and the calibration of the model’s parameters was carried out. When validations are made by such a method, the model provides reliable results, and the method becomes innovative because of the originality and honesty of dimensions with each application.

These assessments determine the trustworthiness and accuracy of the questions inside the concepts and the capacity of the model being studied to differentiate between different concepts and align with other related concepts. Significant standardized loading factors (λ) are indicative of robust convergent validity. As per the criteria established by Hair et al.44, a loading factor of λ > 0.5 signifies an acceptable level of convergent validity. The external model loadings, as presented in Table 2 and Fig. 3, provide insight into the results of the convergent validity assessment on food insecurity determinants. All constructs exhibit high levels of reliability and validity, surpassing the benchmark and meeting the criteria for further investigation.

The indicators “Agri_Prac1” and “Agri_Prac3” demonstrate a robust association (loading = 0.996) with both latent constructs “Agri_Prac,” suggesting both adequately reflect high dimensions of agricultural practices within the studied context.

The indicators CCH1, CCH2, CCH3, and CCH4 show strong associations with the latent construct “Climate Change” (CCH), with high loadings (0.916, 0.958, 0.926, and 0.937 respectively). This indicates that these indicators effectively represent climate change and are pivotal in capturing essential aspects. The Food Insecurity Index (FISI) comprises eight indicators, with loading values as follows: FISI1 (0.609), FISI2 (0.491), FISI3 (0.495), FISI4 (0.867), FISI5 (0.854), FISI6 (0.767), FISI7 (0.865), and FISI8 (0.736). The loadings indicate the association between indicators and the construct of food insecurity, with FISI2, FISI3, and FISI5 showing lower outer loadings than recommended thresholds. Despite this, the decision to retain these items is supported by literature on scale development and validation, which suggests that strict adherence to cutoff values may overlook items that enhance construct validity and reliability44,45. Recent psychometric research emphasizes the importance of evaluating each item’s contribution to the overall measurement model rather than relying solely on cutoff values46. This study considers a specific population where certain items may have unique relevance to food security, allowing for the retention of lower-loading items that are conceptually relevant and statistically validated within the study context.

In Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), assessing the model fit is crucial to regulate how well the hypothesized model aligns with the data observed. Various fit indices are employed to evaluate model fitness. These fit indices provide information about how well the planned model aligns with the data observed.

The fit indices presented in Table 3, suggest a reasonable fit of the estimated model to the data. The SRMR value of 0.083 indicates an average residual of approximately 8.3% of the standard deviation of the dependent variable, suggesting a reasonable fit. However, the d_ULS (unweighted least squares) value of 0.727 and the d_G (geodesic distance) value of 0.314 indicate a moderate discrepancy between the observed and predicted covariance matrices. The Chi-square (χ2) statistic, which measures the likelihood ratio test statistic, is 849.666 (p < 0.001), indicating a statistically significant difference between the observed and predicted frequencies. Nevertheless, the NFI (Normed Fit Index) value of 0.858 indicates that the estimated model fits the data approximately 86% better than a null model, suggesting a good relative fit. Overall, while the model is a reasonable representation of the data, some discrepancy exists between observed and predicted relationships, suggesting potential avenues for model improvement.

The Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio matrix provides evidence for the discriminant validity of the constructs, indicating that each construct measures a unique and distinct concept. Table 4 reflects the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio.

The Monotrait correlations on the diagonal are substantially higher than the Heterotrait correlations, suggesting that each construct is more closely related to itself than to other constructs. Specifically, agricultural practices (Agri_Prac) are distinct from conservation behaviors (CCH) and food security intentions (FISI), with low correlations between Agri_Prac and CCH (0.060) and Agri_Prac and FISI (0.206). While there is some overlap between conservation behaviors and food security intentions (CCH and FISI, 0.237), the constructs generally demonstrate good discriminant validity. This supports the idea that each construct measures a distinct concept, providing a solid foundation for further analysis.

The Fornell–Larcker criterion results support the discriminant validity of the constructs, indicating that each measures a unique and distinct concept. Table 5 presents the results of the Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

The high diagonal values (all above 0.7) demonstrate strong convergent validity, with indicators strongly related to their respective constructs. In contrast, the off-diagonal values are all low (below 0.3), confirming that the constructs are distinct and not overly correlated. Specifically, Agricultural Practices (Agri_Prac) shows weak and negative relationships with both Conservation Behaviors (CCH) and Food Security Intentions (FISI), while CCH and FISI have a weak and positive relationship. These results provide robust evidence for the discriminant validity of the constructs, supporting the idea that each measures a distinct concept.

Structural model evaluation (inner model) and hypothesis testing

Structural models describe the relationship between latent variables. In partial least squares, the route variable coefficient is derived using the weight of the structural model as indicated by the t-statistic value obtained during the bootstrapping stage with a sample size of 415. The inner model path parameter coefficient result in Punjab (Pakistan) is shown in Table 6 and Fig. 4.

The results in Table 6 indicate a statistically significant positive relationship between age and food insecurity, as evidenced by the coefficient for ‘Age’ (0.097, p = 0.039). As individuals age, they may experience physical decline, social isolation, reduced resources, and increased healthcare expenses, leading to food insecurity. Older farmers may struggle with modern techniques, and age-related mobility issues can limit access to food sources. Studies confirm that the age of the household head is positively related to food insecurity47,48. Younger farmers tend to be more productive and food secure, while households headed by older individuals are more likely to experience food insecurity. Considering the age of the household head is crucial in addressing food insecurity.

The coefficient for education is − 0.189 (p = 0.000), indicating that each unit increase in education level leads to a statistically significant decrease in food insecurity by 0.189 units. Higher education serves as a protective factor against food insecurity by equipping individuals with knowledge, skills, and critical thinking abilities, enabling them to make informed decisions about food access, nutrition, and resource management. This finding is consistent with previous research: Gebre49 reported that educated household heads are less likely to experience food insecurity, Ibukun and Abayomi50 noted that highly educated individuals are less likely to face severe food insecurity, and Muche et al.51 found a positive relationship between educational status and household food security. Improving educational access and quality is crucial to leveraging education’s potential to alleviate food insecurity in rural AJK. To achieve this, infrastructure development is essential, focusing on building and upgrading schools in remote areas. Localized vocational training programs in agriculture, livestock management, and entrepreneurship can equip rural youth with relevant skills. Incorporating agricultural and nutrition education into school curricula can promote sustainable farming practices and healthy eating habits. Scholarship programs, particularly for disadvantaged girls, can incentivize education. Adult literacy programs, targeting rural adults, can focus on basic life skills and numeracy. Given AJK’s resource constraints, partnerships with local NGOs and community organizations are vital. Teacher training and capacity-building programs can ensure the effective delivery of context-specific education. Digital education platforms can supplement traditional teaching methods, overcoming geographical barriers. Female empowerment initiatives, promoting girls’ education and women’s literacy, are critical. Skill development programs in income-generating activities like handicrafts and food processing can enhance economic opportunities. Awareness campaigns highlighting education’s role in food security and economic development can engage local communities. Implementing these strategies requires a phased approach, prioritizing feasible initiatives and gradually scaling up. Collaborative efforts between government, NGOs, and local stakeholders can ensure sustainable progress, empowering rural AJK communities to address food insecurity and foster economic resilience.

The gender coefficient (0.470, p = 0.000) indicates females experience higher food insecurity than males. This aligns with existing literature on gendered dynamics, where women face additional barriers to accessing nutritious food. Our study reinforces the previous findings of Fadol et al.52, and Awoke et al.53, and Hakim et al.54 all found male leadership or farming is associated with improved food security.

The household size coefficient (0.499, p < 0.000) indicates that each unit increase in household size leads to a significant rise in food insecurity by 0.499 units. Larger households tend to experience higher food insecurity due to increased resource requirements, reduced access to nutritious food per capita, and competition for limited resources. This indicates that larger households tend to experience higher levels of Food Insecurity. This finding is intuitive, as larger households typically require more resources to meet their basic needs, including food. Additionally, households with more members may face economies of scale in food production and purchasing, reducing access to nutritious food per capita. Furthermore, larger households may also experience increased competition for limited resources, exacerbating food insecurity. Our findings concur with previous studies. The findings of Muche et al.51, Obayelu and Olufunke55, and Ademola et al.56 indicate that there is a negative correlation between family size and household food security, while larger livestock numbers are linked to increased food security. These studies show that household food poverty increases with larger household sizes.

Food insecurity is significantly reduced by 0.582 units for every unit increase in income, according to the income coefficient estimate (− 0.582, p < 0.000), demonstrating the important role income plays in reducing food insecurity. A higher salary offers financial stability, which makes it possible for people to buy wholesome food, have access to superior healthcare, education, and social support systems, as well as to make educated decisions regarding their nutrition and well-being. Our results are consistent with previous studies. Income and food security have been found to positively correlate by Tan et al.57, Dunga58 found that higher income is linked to a higher Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) and an increased likelihood of food security, Tabrizi et al.59 found that income and food security are positively correlated, and Sisha (2020)60 found that wealthier households are less likely to experience food insecurity. This research supports our findings, highlighting the significance of wealth and income in attaining food security.

Being married is associated with a significant increase in food insecurity (coefficient − 0.466, p = 0.021) due to unique challenges such as increased financial responsibilities, reduced economic autonomy, and changed social dynamics. Additionally, married couples may have more dependents, leading to increased food needs and expenses, which can contribute to food insecurity. These factors may outweigh the potential benefits of marriage, such as shared resources and support, leading to a higher likelihood of food insecurity among married households. Our results are consistent with prior studies. Tabrizi et al.59 identified marital status as a significant predictor of food insecurity. Mello et al.61 found that married households are more likely to experience food insecurity. Aidoo et al.62 discovered that unmarried households are more likely to be food secure. Getaneh et al.63 found a negative relationship between marital status and food insecurity, suggesting that married households face increased expenses and social responsibilities that contribute to food insecurity pressures.

The coefficient of − 0.109 indicates a negative correlation between remittances and food insecurity; however, the p-value of 0.460 suggests that this relationship lacks statistical significance. The absence of statistical significance may result from the restricted number of households receiving remittances, complicating the detection of a significant relationship. Furthermore, the traits of households that receive remittances may vary considerably from those that do not, potentially obscuring any relationship with food security. The limited sample size of households receiving remittances may also account for the insignificant findings. The identified limitations may have concealed any possible correlation between remittances and food security. Our research aligns with existing studies, indicating that remittances significantly affect household food security. Our research corroborates existing studies indicating that remittances significantly influence household food security. Moniruzzaman64, Mora-Rivera and Edwin65, and Barnabas et al.66 demonstrate that remittances enhance food security indicators, serving as an essential safety net and coping strategy for food insecurity. Remittances significantly contribute to alleviating food insecurity by diminishing uncertainty and addressing food-related shocks.

A significant negative coefficient of − 0.143 (p = 0.000) indicates that increased engagement in agricultural practices is associated with a decrease in food insecurity by 0.143 units. This suggests that heightened agricultural activity leads to increased food production and availability, reducing food insecurity. These findings align with previous research. Joshi and Joshi67 found a positive association between agricultural engagement and food security, Mughal68 examined the impact of increased cereal production on food security, and Diallo et al.69 found a positive association between household food security and the adoption of short-duration crops. These studies highlight the importance of agricultural practices in reducing food insecurity.

The coefficient of climate change (0.140, p = 0.000) indicates that each unit increase in climate variations is associated with a 0.140-unit increase in food insecurity. This suggests that climate change corresponds to increased food insecurity, possibly due to climate-related stressors like droughts or floods, which exacerbate underlying vulnerabilities like poverty and resource limitations. Our findings align with previous research. Leisner70 found climate change threatens food supplies, Alam et al.71 identified climate change as a factor in riverbank erosion and food insecurity, and Verschuur et al.72 highlighted climate change’s role in Lesotho’s 2007 food crisis. These studies collectively emphasize the urgent need to address climate change’s devastating effects on food security.

Table 7 presents the results of the regression analysis, showing the relationships between the independent variables (Age, Household Size, Gender, Marital Status, Education, Income, Remittances, Agricultural Practices, and Climate Change) and the dependent variable (Food Insecurity Index—FISI). Age, Household Size, Gender, Marital Status, Education, Income, Agricultural Practices, and Climate Change have a significant relationship with the Food Insecurity Index (FISI), with p-values less than 0.05. Specifically, a one-unit increase in Age, Household Size, Gender (male), Marital Status (married), Education, Income, Agricultural Practices, and Climate Change leads to a significant increase in FISI. On the other hand, Remittances do not have a significant relationship with FISI (p-value = 0.460). The t-values and significance levels (Sig.) support these findings, with t-values ranging from 2.070 to 10.523 and significance levels less than 0.05, indicating acceptance of the respective hypotheses (H1 to H9).

Conclusion and policy recommendations

Food insecurity remains a pressing concern in rural Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), with far-reaching consequences for the well-being and livelihoods of vulnerable communities. A systematic approach is presented to identify and address the root causes of food insecurity. This study aimed to investigate the complex relationships between food insecurity, household factors, agricultural practices, and climate change in Poonch District, AJK. The findings reveal that food insecurity is significantly associated with household factors such as age, education, gender, household size, income, and marital status, as well as with agricultural practices and climate change, while remittances are insignificant. The findings underscore the significance of household and environmental factors in understanding and addressing food insecurity, necessitating a more concentrated effort to tackle this challenge. This study deepens our grasp of the underlying factors driving food insecurity, providing valuable insights for policymakers, researchers, and practitioners seeking to combat this pressing issue. Climate change is positively associated with food insecurity, while agricultural practices are negatively related to it. Similarly, household factors such as age, being female, and household size favorably impacted with food insecurity, whereas education, income, and being unmarried are negatively linked with it. Notably, remittances were found to be insignificant, likely because most respondents do not receive remittances, and even if they do, the amount is unlikely to be sufficient to significantly impact household food insecurity status. This study’s findings have significant implications for addressing food insecurity. Theoretically, it advances the existing literature by identifying complex relationships between food insecurity with household factors, agricultural practices, and climate change. The results highlight the importance of considering household and environmental factors and underscore the need for sustainable, locally-driven solutions. By informing evidence-based policy and practice, this study aims to improve the well-being and livelihoods of vulnerable communities.

Several policy implications arise from the study’s findings. Food insecurity, family relationships, farming methods, and climate change all interact in complex ways, and policy responses should first recognize this. For effective policy creation, it is necessary to address these elements holistically. Second, because of their increased risk of food insecurity, policy should prioritize aiding low-income, uneducated, and single-person households. One approach could be to create individualized support programs that address their unique requirements. Thirdly, to lessen the impact of climate change on food security, we must encourage agricultural techniques that are resilient to the effects of climate change. Sustainable farming practices and hardy crop varieties may be incentivized as a result. To end food insecurity, it is crucial to enable local communities to find their solutions. Instead of depending on outside funding, this method encourages community ownership and long-term viability. Fifthly, policies should work to eliminate age and gender gaps in educational opportunities, income, and resources; these gaps worsen food insecurity. Promoting inclusive development requires guaranteeing equal opportunity. To protect food security from environmental threats, it is crucial to prioritize efforts for adapting to and reducing the impact of climate change. This requires taking preventative actions to lessen the blow that climate change will deal to agricultural output and food security. Equally important is ensuring that low-income families have a better opportunity to earn an income and further their education. An individual’s ability to provide a sufficient food supply for their family can be enhanced through increased economic empowerment and better educational opportunities. The effectiveness of policy initiatives can only be determined by consistent monitoring and assessment, which is essential for making decisions based on evidence. Policymakers are better able to respond to changing needs and circumstances when they conduct continuous assessments to make sure programs are still relevant.

Limitations of study

The study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, most respondents were uneducated, which may have led to some being shy or hesitant to share accurate information. Moreover, despite clarifying the academic purpose of the study, some respondents may have perceived the interview as an opportunity to receive assistance from an NGO, potentially leading to manipulated responses. This may have resulted in biased or inaccurate data, which could impact the validity of the findings. Additionally, the sample size of 470 households may not be representative of the entire population of Poonch District, AJK. Furthermore, the study did not account for other potential factors that may influence food insecurity, such as conflict, access to healthcare, and geographical constraints like remote location, mountainous terrain, etc. These limitations may impact the generalizability of the findings to other regions or contexts with different socioeconomic and environmental conditions.

Future scope

Future research should aim to address these limitations by collecting more objective data, increasing the sample size, and exploring the impact of additional factors on food insecurity. The study’s findings should be used to inform policy and practice, and future research should evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at addressing food insecurity in the region. This study provides a foundation for future research to build upon and identify sustainable solutions to address food insecurity in rural Azad Kashmir by exploring the complex relationships between food insecurity, household factors, agricultural practices, and climate change.

References

Khurshid, N. & Abid, E. Unraveling the complexity! Exploring asymmetries in climate change, political globalization, and food security in the case of Pakistan. Res. Glob. 8, 100220 (2024).

Bondad-Reantaso, M. G., Subasinghe, R. P., Josupeit, H., Cai, J. & Zhou, X. The role of crustacean fisheries and aquaculture in global food security: Past, present and future. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 110(2), 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2012.03.010 (2012).

Ali, I., Arslan, A., Chowdhury, M., Khan, Z. & Tarba, S. Y. Reimagining global food value chains through effective resilience to COVID-19 shocks and similar future events: A dynamic capability perspective. J. Bus. Res. 141, 1–12 (2022).

FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2023: Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation, and healthy diets across the rural-urban continuum. FAO https://doi.org/10.4060/cc3017en (2023).

Shahzad, M. A., Razzaq, A., Wang, L., Zhou, Y. & Qin, S. Impact of COVID-19 on dietary diversity and food security in Pakistan: A comprehensive analysis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 110, 104642 (2024).

Khurshid, N., Ajab, S., Tabash, M. I. & Barbulescu, M. Asymmetries in climate change and livestock productivity: non-linear evidence from autoregressive distribution lag mode. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7, 1139631 (2023).

Devi, K., Singh, A. D., Dhiman, S., Kumar, D., Sharma, R. et al. Food security under changing environmental conditions. In Food Security in a Developing World: Status, Challenges, and Opportunities 299–326 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024).

Abbas, S. Climate change and major crop production evidence from Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(4), 5406–5414 (2022).

Khurshid, N., Fiaz, A., Ali, K. & Khurshid, J. Climate change shocks and economic growth: a new insight from non-linear analysis. Front. Environ. Sci., 2111 (2022).

Aboaba, K. O., Fadiji, D. M. & Hussayn, J. A. Determinants of food security among rural households in Southwestern Nigeria USDA food security questionnaire core module approach. J. Agribusiness Rural Dev. 2 (2020).

Khurshid, N., Khurshid, J., Shakoor, U. & Ali, K. Asymmetric Effect of Agriculture Value Added on CO2 emission: Does globalization and energy consumption matter for Pakistan? Front. Energy Res., 1796 (2022).

Ahmad, D. & Afzal, M. Flood hazards, human displacement and food insecurity in rural riverine areas of Punjab, Pakistan policy implications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(8), 10125–10139 (2021).

Rasul, G., Hussain, A., Khan, M. A., Ahmad, F. & Jasra, A. W. Towards a framework for achieving food security in the mountains of Pakistan (2014).

WFP Pakistan Floods Situation Report, September 2023—Pakistan. ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/Pakistan/wfp-pakistan-floods-situation-report-september-2023 (2023).

Islamic Relief Pakistan. Increased impacts of climate change on water resources and livelihood in the districts Muzaffarabad, Bagh and Haveli AJK [Report]. Retrieved from https://islamic-relief.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Final-Report-Rev-11-30-23-reduced-size.pdf (2023).

The Nation. The climate crisis has a profound impact on AJK’s small farmers. Retrieved from https://www.nation.com.pk/28-Aug-2023/climate-crisis-has-profound-impact-on-ajk-s-small-farmers (2023).

Afridi, G. S., Ishaq, M. & Jabbar, A. Food security assessment in Azad Jammu and Kashmir empirical: analysis of dietary diversity, current and project food demand and supply-demand gap. J. Appl. Econ. Bus. Stud. 4(3), 185–198 (2020).

AJK P&D. *AJK Policy Brief Situation Analysis of Poverty, Agriculture, Health, Education, and WASH.* Retrieved from https://www.sdgpakistan.pk/uploads/pub/Policy_Brief_AJK.pdf (2018).

AJK P&D. AJK Statistical Year Book 2022. Retrieved from https://pndajk.gov.pk/uploadfiles/downloads/AJK%20Statistical%20Year%20Book%202022%20.pdf (2022).

Aziz, N., Nisar, Q. A., Koondhar, M. A., Meo, M. S. & Rong, K. Analyzing the women’s empowerment and food security nexus in rural areas of Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Pakistan: By considering the sense of land entitlement and infrastructural facilities. Land Use Policy 94, 104529 (2020).

Omotesho, O. A., Adewumi, M. O., Muhammad-Lawal, A. & Ayinde, O. E. Determinants of food security among the rural farming households in Kwara State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Gen. Agric. 2(1) (2016).

Mitiku, A., Fufa, B. & Tadese, B. Empirical analysis of the determinants of rural households’ food security in Southern Ethiopia The case of Shashemene District. Basic Res. J. Agric. Sci. Rev. 1(6), 132–138 (2012).

Habtewold, T. M. Determinants of food security in the Oromiya Region of Ethiopia. In Economic Growth and Development in Ethiopia, 39–65 (2018).

Beyene, F. & Muche, M. Determinants of food security among rural households of Central Ethiopia. An empirical analysis. Q. J. Int. Agric. 49(4), 299–318 (2010).

Aragie, T. & Genanu, S. Level and determinants of food security in north Wollo zone (Amhara region–Ethiopia). J. Food Secur. 5(6), 232–247 (2017).

Oyebanjo, O., Ambali, O. I. & Akerele, E. O. Determinants of food security status and incidence of food insecurity among rural farming households in Ijebu Division of Ogun State Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci. Environ. 13(1), 92–103 (2013).

Sekhampu, T. J. Determination of the factors affecting the food security status of households in Bophelong, South Africa. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. (IBER) 12(5), 543–550 (2013).

Mustapha, M., Kamaruddin, R. B. & Dewi, S. Factors affecting rural farming households food security status in Kano, Nigeria. Int. J. Manag. Res. Rev. 8(9), 1 (2018).

Zakari, S., Ying, L. & Song, B. Factors influencing household food security in West Africa The case of Southern Niger. Sustainability 6(3), 1191–1202 (2014).

Wali, M. Q. K., Alam, A. & Shah, I. Household food security determinants and perceived challenges in mountains of Azad Jammu and Kashmir. Sarhad J. Agric. 37(3), 957 (2021).

Khurshid, N., Emmanuel Egbe, C., Fiaz, A. & Sheraz, A. Globalization and economic stability: an insight from the rocket and feather hypothesis in Pakistan. Sustainability 15(2), 1611 (2023).

Megersa, B., Markemann, A., Angassa, A. & Valle Zárate, A. The role of livestock diversification in ensuring household food security under a changing climate in Borana, Ethiopia. Food Secur. 6, 15–28 (2014).

Akukwe, T. I. Household food security and its determinants in agrarian communities of southeastern Nigeria. Agro-Science 19(1), 54–60 (2020).

Yusuf, S. A., Balogun, O. L. & Falegbe, O. E. Effect of urban household farming on food security status in Ibadan metropolis, Oyo State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci. (Belgrade) 60(1), 61–75 (2015).

Masipa, T. The impact of climate change on food security in South Africa. Current realities and challenges ahead. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 9(1), 1–7 (2017).

Bandara, J. S. & Cai, Y. The impact of climate change on food crop productivity, food prices and food security in South Asia. Econ. Anal. Policy 44(4), 451–465 (2014).

Ani, K. J., Anyika, V. O. & Mutambara, E. The impact of climate change on food and human security in Nigeria. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 14(2), 148–167 (2021).

Godde, C. M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Mayberry, D. E., Thornton, P. K. & Herrero, M. Impacts of climate change on the livestock food supply chain; a review of the evidence. Glob. Food Secur. 28, 100488 (2021).

Pickson, R. B. & Boateng, E. Is climate change a friend or foe to food security in Africa? In Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1–26 (2022).

Ballard, T. J., Kepple, A. W., Cafiero, C. & Schmidhuber, J. Better measurement of food insecurity in the context of enhancing nutrition. Ernahrungs Umschau 61(2), 38–41 (2014).

Dasgupta, S. & Robinson, E. J. Attributing changes in food insecurity to a changing climate. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 4709 (2022).

Antriyandarti, E., Suprihatin, D. N., Pangesti, A. W. & Samputra, P. L. The dual role of women in food security and agriculture in responding to climate change Empirical evidence from Rural Java. Environ. Challenges 14, 100852 (2024).

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. & Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis 7th edn. (Prentice Hall, 2010).

Onori, F. et al. An adaptation of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) for measuring food insecurity among women in socially backward communities. Asian J. Agric. Dev. 18(1), 66–82 (2021).

Munir, F., Khurshid, N. & Khurshid, J. Unveiling the relation between household energy conservation and subjective well-being: insights from structural equation modeling. Heliyon (2024).

Marsh, H. W., Morin, A. J. S., Parker, P. D. & Kaur, G. Exploratory structural equation modeling: an integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 10, 85–110 (2014).

Echebiri, R. N. & Onu, D. O. Risk management strategies among smallholder arable crop farmers in Ibiono Ibom Local Governemet Area, Akwaibom State, Nigeria. Nigeria Agric. J. 50(1), 22–29 (2019).

Ehebhamen, O. G., Obayelu, A. E., Vaughan, I. O. & Afolabi, W. A. O. Rural households’ food security status and coping strategies in Edo State Nigeria. Int. Food Res. J. 24(1) (2017).

Gebre, G. G. Prevalence of household food insecurity in East Africa Linking food access with climate vulnerability. Clim. Risk Manag. 33, 100333 (2021).

Ibukun, C. O. & Adebayo, A. A. Household food security and the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Afr. Dev. Rev. 33, S75–S87 (2021).

Muche, M., Endalew, B. & Koricho, T. Determinants of household food security among Southwest Ethiopia rural households. Food Sci. Technol. 2(7), 93–100 (2014).

Fadol, A. A., Tong, G., Raza, A. & Mohamed, W. Socioeconomic determinants of household food security in the Red Sea state of Sudan: Insights from a cross-sectional survey. GeoJournal 89(2), 69 (2024).

Awoke, W., Eniyew, K., Agitew, G. & Meseret, B. Determinants of food security status of household in Central and North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. Cogent Soc. Sci. 8(1), 2040138 (2022).

Hakim, R., Haryanto, T. & Sari, D. W. Technical efficiency among agricultural households and determinants of food security in East Java, Indonesia. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 4141 (2021).

Obayelu, O. A. & Orosile, O. R. Rural livelihood and food poverty in Ekiti State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Environ. Int. Dev. (JAEID) 109(2), 307–323 (2015).

Adeleke, O., Isaac, A. & Ademola, A. Determinants of food security status and coping strategies to food insecurity among rural crop farming households in Ondo State, Nigeria. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 13(7), 39–50 (2021).

Tan, S. T., Tan, C. X. & Tan, S. S. Food security during the COVID-19 home confinement: A cross-sectional study focusing on adults in Malaysia. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 27, 200142 (2022).

Dunga, H. M. An empirical analysis on determinants of food security among female-headed households in South Africa. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Human. Stud. 12(1), 66–81 (2020).

Tabrizi, J. S., Nikniaz, L., Sadeghi-Bazargani, H., Farahbakhsh, M., & Nikniaz, Z. Socio-demographic determinants of household food insecurity among Iranians: a population-based study from northwest of Iran. Iran. J. Public Health 47(6), 893 (2018).

Sisha, T. A. Household level food insecurity assessment: Evidence from panel data, Ethiopia. Sci. Afr. 7, e00262 (2020).

Mello, J. A. et al. How is food insecurity associated with dietary behaviors? An analysis with low-income, ethnically diverse participants in a nutrition intervention study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 110(12), 1906–1911 (2010).

Aidoo, R., Mensah, J. O. & Tuffour, T. Determinants of household food security in the Sekyere-Afram plains district of Ghana. Eur. Sci. J. 9(21) (2013).

Getaneh, Y., Alemu, A., Ganewo, Z. & Haile, A. Food security status and determinants in North-Eastern Rift Valley of Ethiopia. J. Agric. Food Res. 8, 100290 (2022).

Moniruzzaman, M. The Impact of remittances on household food security: Evidence from a survey in Bangladesh. Migrat. Dev. 11(3), 352–371 (2022).

Mora-Rivera, J. & van Gameren, E. The impact of remittances on food insecurity: Evidence from Mexico. World Dev. 140, 105349 (2021).

Barnabas, B., Bavorova, M., Zhllima, E., Imami, D., Pilarova, T., Madaki, M. Y. & Awalu, U. The effect of food and financial remittances on household food security in Northern Nigeria. J. Asian Afr. Stud., 00219096241235293 (2023).

Joshi, G. R. & Joshi, N. B. Determinants of Household Food Security in the Eastern Region of Nepal, 174–188 (2016).

Mughal, M. & Fontan Sers, C. Cereal production, undernourishment, and food insecurity in South Asia. Rev. Dev. Econ. 24(2), 524–545 (2020).

Diallo, A., Donkor, E. & Owusu, V. Climate change adaptation strategies, productivity and sustainable food security in southern Mali. Clim. Change 159(3), 309–327 (2020).

Leisner, C. P. Climate change impacts food security on perennial cropping systems and nutritional value. Plant Sci. 293, 110412 (2020).

Alam, G. M., Alam, K., Mushtaq, S., Sarker, M. N. I. & Hossain, M. Hazards, food insecurity and human displacement in rural riverine Bangladesh: Policy implications. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 43, 101364 (2020).

Verschuur, J., Li, S., Wolski, P. & Otto, F. E. Climate change as a driver of food insecurity in the 2007 Lesotho-South Africa drought. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 3852 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khurshid, N., Gohar, A.M. Integrated analysis of local agricultural practices, community-led interventions, and climate change impacts on food insecurity in rural Azad Kashmir. Sci Rep 15, 8375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82749-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82749-1