Abstract

Using postnatal care (PNC) within the first week following childbirth is crucial, as both the mother and her baby are particularly vulnerable to infections and mortality during this period. In this study, we examined the factors associated with early postnatal care (EPNC) use in Afghanistan. We used data from the multiple indicator cluster survey (MICS) 2022–2023. The study population was ever-married women who delivered a live child during their recent pregnancy within the 2 years preceding MICS 2022–23. The outcome was EPNC and defined as the first check of the mother within the first week of delivery. A binary logistic regression was used, and odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI were obtained. Out of 12,578 women, 16.0% received EPNC. EPNC was lower in women who delivered at home [AOR 0.35 (95% CI 0.28–0.44)] compared with women who delivered at public clinics. EPNC was higher in women with ≥ 4 antenatal care (ANC) visits [1.29 (1.02–162)], in women in the highest quintile of wealth status [1.70 (1.25–2.32)], and in women with access to radio [1.76 (1.45–2.15)]. EPNC use among Afghan women remains low (16.0%). Key factors associated with ENPC utilization include place of delivery, ANC utilization, wealth status, and radio access.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postnatal care (PNC) services have been identified as a fundamental component of the continuum of maternal, newborn, and child care, and one of the key indicators in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on reproductive, maternal, and child health, including reducing maternal mortality rates and ending preventable neonatal deaths1. The postnatal period is defined as the period starting immediately after childbirth and lasting up to 6 weeks (42 days) and is a critical time for the health and well-being of women and newborns1. The burden of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity in the postnatal period is still unacceptably high in low and middle-income countries (LIMCs)1,2,3. The risk of maternal mortality is high within the first 2 days after delivery4,5, as serious complications may occur in this period, leading to the death of the mother6. Additionally, the risk of neonatal mortality is also high during the first week after birth7,8. Opportunities to increase maternal well-being and to improve neonatal care during the postnatal period have not been fully utilized1. Utilizing postnatal care, especially within the first week of childbirth is crucial to the management of complications and detection of postnatal danger signs6. WHO recommends the first postnatal visit within 24 h of childbirth, and a minimum of three additional postnatal visits timed at 3 days (48–72 h), 7–14 days, and 6 weeks after delivery1. The use of early postnatal care (EPNC), defined as the first check of the mother within the first week of childbirth9,10,11, however, is still at very low levels in many LMICs12,13,14,15,16.

Afghanistan is one of the fragile states, with a very high maternal mortality rate (MMR)17. MMR in Afghanistan gradually declined from 1450 deaths in 2000 to 638 deaths per 100,000 live births in 201718. In spite of the noticeable progress over the past 2 decades, MMR in Afghanistan remains one of the highest globally and among its neighbouring countries18. Since August 2021 when the internationally assisted Afghan government collapsed, there has been growing concern over the worsening humanitarian crises and funding restrictions for public services and the health system19,20. Recent studies show that in addition to the low coverage and utilization of maternal health services21,22, women disproportionately have a higher prevalence of non-communicable diseases23,24, and they encounter many mental health challenges and discrimination in Afghanistan25,26.

Of several studies conducted in Afghanistan on maternal health services, only two studies have examined PNC utilization in recent years in the country21,27. Of the two studies, one examined factors associated with the utilization of at least one PNC visit27, and the other one studied factors associated with the utilization of ≥ 4 PNC visits21. These studies showed that the prevalence of receiving at least one PNC was 44%27, and only 2% of women received ≥ 4 PNC visits21. Both studies found that education was significantly associated with higher use of PNC services21,27. Women’s age, residential area (urban vs rural), parity, access to radio, place of childbirth, and attendance to at least 4 ANC visits were significantly associated with higher utilization of at least one PNC visit27. Women’s knowledge of signs and symptoms suggestive of complicated pregnancy, and deliveries conducted by skilled birth attendants (SBAs) such as doctors, midwives, and nurses were significantly associated with the use of ≥ 4 PNC visits21. However, despite these findings, the correlates of EPNC utilization have yet to be adequately addressed.

Research shows that suboptimal utilization of healthcare services during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period is a contributing factor to grave pregnancy outcomes28. Given the paucity of research on the use of PNC services in Afghanistan, we examined the prevalence and factors associated with EPNC use. By determining the prevalence of EPNC use and exploring the factors associated with it, our study aims to contribute vital insights into the dynamics of PNC utilization among Afghan women, thereby informing targeted interventions and policy initiatives aimed at bolstering maternal and child health outcomes in the country.

Methods

Data source and study population

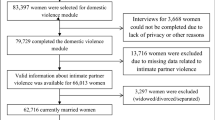

In this cross-sectional study, we used data from the multiple indicator cluster survey (MICS) 2022–2023, which collected data from a nationally representative sample in Afghanistan29. The sampling approach and data collection process have been described elsewhere29. During the survey, data were collected from reproductive-age women by trained surveyors29. In this study, we used data from 12,578 ever-married women, aged 15–49 years, who delivered a live child in the last 2 years prior to the survey (Fig. 1).

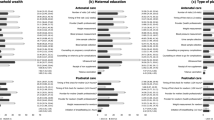

A modified version of Andersen’s behavioral model for healthcare utilization, which was used in previous studies9,30, was employed to create a conceptual framework for women who utilized early postnatal care services (Fig. 2). In light of the conceptual framework, we have specified our logistic regression analysis, assessing the effects of variables under the predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors on using EPNC.

Study variables

The outcome was EPNC, defined as the first check of the mother within the first week of childbirth1,9,10,31. The interviewees’ responses to questions “Was she checked after delivery? (yes/no)” and “How long after delivery did the first of this check happen? (hours/days/weeks/don’t know)” were used to create the outcome variable (binary variable).

The explanatory variables were women’s age at the time of survey (15–29, 30–39, 40–49 years), women’s education (no formal education, primary education, secondary/higher education), wealth status (lowest quintile up to highest quintile), residential area (urban vs rural), place of delivery (public clinic/health post, public hospital, private clinic or hospital, at home), antenatal care (ANC) use (no ANC visit, 1–3 ANC visits, and ≥ 4 ANC visits), woman used a mobile phone at least once a week in the last 3 months (yes/no), woman watched TV at least once a week (yes/no), and woman listened to the radio at least once a week (yes/no). Details on the construction of the variable on wealth status are provided in the MICS 2022–23 report29.

Statistical analysis

We examined the distribution of baseline characteristics of women, using the chi-square test. We have also provided the prevalence of EPNC and the provision of EPNC by healthcare provider type.

We specified and fitted a binary logistic regression model (see below).

\({Y}_{ij}\) refers to the outcome variable for woman i (whether she received EPNC: yes vs no), with j category of explanatory variables. \({X}_{ij}\) denotes a vector of explanatory variables, and \(k\) refers to the number of explanatory variables. β0 stands for the intercept term, and βj refers to the odds ratio (OR) for each category of explanatory variables, except the reference category of each variable. \({\upvarepsilon }_{ij}\) refers to the error term.

We run the model for bivariate and multivariate analyses. For the multivariate analysis, we retained the variables that had a p-value of less than 0.25 in the bivariate analysis. We used data with complete information and excluded those with missing values (see Fig. 1). Sampling design and weights were applied by defining the survey strata, primary sampling unit, and sampling weight in STATA 17. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

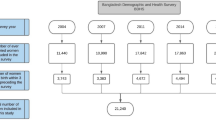

Figure 3 shows that 16.0% of 12,578 women received EPNC. Characteristics of women by status of EPNC are presented in Table 1. Over 60% of women were 15–29 years old. There were significant differences in favor of women’s education, higher wealth status, living in urban versus rural areas, use of ANC services, deliveries at public hospitals, use of mobile phones, and access to media between women who received EPNC and those women who did not. For example, 19.5% of women who received EPNC versus 12.4% of women who did not receive it were women with secondary/higher education (details in Table 1).

Figure 4 shows that out of 2148 women who received EPNC, 51%, 36%, and 5% of the services were provided by midwives/nurses, doctors, and community health workers/traditional birth attendants, respectively.

The multivariate results in Table 2 show that it was less likely for women who delivered at home to receive EPNC, compared to women who delivered in public clinics or health posts [AOR 0.35 (95% CI 0.28–0.44)]. It was more likely for women at the highest quintile to receive EPNC, compared to women at the lowest quintile of wealth status [1.70 (1.25–2.32)]. Use of ANC services during pregnancy was significantly associated with EPNC [1.29 (1.02–1.62)] for ≥ 4 ANC visits, compared to women who did not have an ANC visit. Women with access to radio had a higher likelihood of using EPNC [1.76 (1.45–2.15)], compared to women with no access to radio.

Discussion

In this study of 12,578 ever-married women who gave live birth in the past 2 years prior to the survey, we found that only 16.0% of women used EPNC. The likelihood of EPNC in women who delivered at home was lower than the women who delivered at public health facilities. Women with higher ANC services, women in the highest wealth quintile, and women with access to radio were positively associated with EPNC use.

The prevalence of EPNC was 16.0% in our study. To our knowledge, no previous study has reported on the prevalence of EPNC in Afghanistan. Findings from other LMICs have shown varying prevalence rates of EPNC. For instance, in Tanzania, 23.6% of women utilized postnatal care within the first week after delivery12. Other studies reported EPNC prevalence ranging from 11.4% in South Sudan14, to 54% in Uganda32. A plausible explanation for the low 16.0% of EPNC use in our study could be related to limited access to health facilities and suboptimal healthcare-seeking practices by women during the first week of childbirth. The importance of EPNC has been well established6. Despite this, it seems likely that after childbirth, families and women would perceive that the pregnancy risks have passed and that the women and newborns are no longer at risk of serious postpartum health conditions; therefore, women and families may become more hesitant to initiate care seeking for PNC during the first week after delivery. Furthermore, in some parts of Afghanistan, cultural beliefs dictate a 40-day post-birth seclusion period due to superstitious beliefs about potential harm to the woman and newborn if they leave home, perpetuated by beliefs in supernatural beings like fairies33.

Our study found a strong association between women’s socioeconomic status and EPNC use, and several studies support our finding9,34. However, findings across studies are inconsistent9,34. For instance, in one study, it was found that women from households with higher income were more likely to receive EPNC, but the associations were only significant for the 2nd and 4th quintiles and not for the 3rd and 5th quintiles of income34. In another study, it was revealed that higher-income households were less likely to receive EPNC compared to the poorest quintile, with significance noted for the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quintiles9. In our study, we found that women from the highest wealth quintile were 1.7 times more likely to use EPNC compared to women from the lowest wealth quintile. Women in the highest wealth quintile have better access to healthcare facilities, providers, media, and educational opportunities, as suggested by previous Afghan studies on maternal healthcare utilization35,36. In terms of policy relevancy, policymakers must prioritize improving EPNC utilization for socioeconomically disadvantaged women to address these inequalities.

Our finding, indicating that women who delivered at home are less likely to use EPNC, aligns with previous studies9,12,13,31,37,38,39,40. Studies from Pakistan and Ethiopia identified that women who gave birth in a health facility were significantly more likely to have EPNC and less likely to delay the first postnatal care within the first week after childbirth38,39. While specific studies on EPNC determinants in Afghanistan are lacking, insights from studies on PNC utilization in the country offer valuable perspectives27. For instance, findings from Afghan PNC studies suggest that women delivering in health facilities are nearly 10 times more likely to utilize at least 1 PNC visit compared to those delivering at home27. Poor access to health facilities as well as poor healthcare-seeking of women for PNC could be a plausible explanation for the lower utilization of EPNC and PNC by women who delivered at home. Therefore, increasing access to institutional deliveries may be a necessary policy consideration for improving EPNC rates in Afghanistan.

In our study, we found that women who had ≥ 4 ANC visits were 1.29 times more likely to use EPNC. The positive association observed between higher use of antenatal care and EPNC utilization in our study is supported by several previous studies9,31,34,37,39,40. For instance, studies from Ethiopia found that women utilizing ANC services, particularly those with 4 or more visits, are more likely to receive EPNC34,37. Another study in Uganda reported similar findings9. Additionally, the studies from Afghanistan also support our finding that utilization of higher ANC visits has a positive association with PNC utilization27,41. The positive association of ANC utilization with EPNC in our study suggests that factors influencing ANC utilization may similarly impact PNC utilization, a trend also noted in recent studies from Afghanistan21,22,41. Therefore, it is highly likely that women who use more ANC services may receive more PNC, including EPNC, services.

Our findings on the association of access to media and EPNC are consistent with a previous study9, which found that women who had access to media were more likely to use EPNC. In our study, we assessed the association of women’s access to TV, radio, and mobile phones with EPNC use. While bivariate analysis revealed significant associations between each of these media sources and EPNC, multivariate analysis indicated that only access to the radio had a statistically significant association with EPNC utilization. Similarly, the study on PNC utilization from Afghanistan reported a significant association between exposure to radio and the use of PNC services27. Studies from other LMICs reported similar findings42,43. In Afghanistan, radio broadcasts remain a potential platform for delivering health messages to the general public35. Therefore, investing in media-based educational programs may be an effective method to improve maternal healthcare knowledge and utilization in this population.

Strengths and limitations

There are some strengths and weaknesses in our study. Our study is the first that examined EPNC utilization in Afghanistan, using data from a nationally representative sample of MICS survey conducted in 2022 and 2023. Given that the data used in our study come from a nationally representative sample, our findings may have external validity, providing the most up-to-date evidence on the factors that influence EPNC use in Afghanistan. The first weakness in our study is the potential of recall bias as women who were interviewed may not have remembered all the information and they may have either over or under-reported the information they provided. The second weakness is the 166 responses on the type of health providers who provided EPNC services, but the interviewee women did not specify the type of health providers. Further, the survey questionnaire did not include separate response options for midwives and nurses; therefore, we could not disintegrate the type of postnatal care midwives and nurses provided within the first week.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that EPNC utilization in Afghanistan remains markedly low at 16.0%. Women with frequent antenatal care visits, those from higher wealth quintiles, and those with radio access were more likely to utilize EPNC. Conversely, home delivery was associated with a reduced likelihood of EPNC use. Further research is essential to identify barriers to postnatal care, including logistical and cultural challenges, to inform interventions that strengthen maternal and neonatal health outcomes across Afghanistan.

Data availability

The MICS 2022–23 dataset is publicly available on UNICEF’s official website through the following link: https://mics.unicef.org/surveys?display=card&keys=Afghanistan.

References

WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Kassebaum, N. J. et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 384, 980–1004 (2014).

Gon, G. et al. The frequency of maternal morbidity: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 141, 20–38 (2018).

World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn. Copyright © World Health Organization 2014 (2013).

Gazeley, U. et al. Women’s risk of death beyond 42 days post partum: A pooled analysis of longitudinal health and demographic surveillance system data in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Glob. Health 10, e1582–e1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(22)00339-4 (2022).

WHO. WHO Technical Consultation on Postpartum and Postnatal Care. Geneva: World Health Organization (2010).

Izulla, P. et al. Proximate and distant determinants of maternal and neonatal mortality in the postnatal period: A scoping review of data from low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One 18, e0293479. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293479 (2023).

Dol, J. et al. Timing of neonatal mortality and severe morbidity during the postnatal period: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 21, 98–199. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbies-21-00479 (2023).

Ndugga, P., Namiyonga, N. K. & Sebuwufu, D. Determinants of early postnatal care attendance: Analysis of the 2016 Uganda demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 1–14 (2020).

Yosef, Y. et al. Prevalence of early postnatal care services usage and associated factors among postnatal women of Wolkite town, Gurage zone, Southern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 13, e061326 (2023).

Yoseph, S., Dache, A. & Dona, A. Prevalence of early postnatal-care service utilization and its associated factors among mothers in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama regional state, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2021, 1–8 (2021).

Konje, E. T. et al. Late initiation and low utilization of postnatal care services among women in the rural setting in Northwest Tanzania: A community-based study using a mixed method approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 635 (2021).

Wassie, G. T. et al. Association between antenatal care utilization pattern and timely initiation of postnatal care checkup: Analysis of 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. PloS One 16, e0258468 (2021).

Izudi, J., Akwang, G. D. & Amongin, D. Early postnatal care use by postpartum mothers in Mundri East County, South Sudan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17, 1–8 (2017).

Appiah, F. et al. Factors influencing early postnatal care utilisation among women: Evidence from the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey. PloS One 16, e0249480 (2021).

Show, K. L., Aung, P. L., Maung, T. M., Myat, S. M. & Tin, K. N. Early postnatal care contact within 24 hours by skilled providers and its determinants among home deliveries in Myanmar: Further analysis of the Myanmar Demographic and Health Survey 2015–16. Plos One 18, e0289869 (2023).

Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Glass, N., Jalalzai, R., Spiegel, P. & Rubenstein, L. The crisis of maternal and child health in Afghanistan. Confl. Health 17, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-023-00522-z (2023).

Essar, M. Y., Ashworth, H. & Nemat, A. Addressing the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan through $10 billion Afghani assets: What are the challenges and opportunities at hand?. Glob. Health 18, 74 (2022).

Essar, M. Y. et al. Afghan women are essential to humanitarian NGO work. Lancet Glob. Health 11(4), e497–e498 (2023).

Tawfiq, E. et al. Predicting maternal healthcare seeking behaviour in Afghanistan: Exploring sociodemographic factors and women’s knowledge of severity of illness. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 561 (2023).

Stanikzai, M. H. et al. Contents of antenatal care services in Afghanistan: Findings from the national health survey 2018. BMC Public Health 23, 2469 (2023).

Neyazi, N., Mosadeghrad, A. M., Tajvar, M. & Safi, N. Trend analysis of noncommunicable diseases and their risk factors in Afghanistan. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 9, 210–221 (2023).

Dadras, O., Stanikzai, M. H., Jafari, M. & Tawfiq, E. Risk factors for non-communicable diseases in Afghanistan: Insights of the nationwide population-based survey in 2018. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 43, 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-024-00625-0 (2024).

Saleem, S. M., Shoib, S., Dazhamyar, A. R. & Chandradasa, M. Afghanistan: Decades of collective trauma, ongoing humanitarian crises, Taliban rulers, and mental health of the displaced population. Asian J. Psychiatry 65, 102854 (2021).

Sarem, S. et al. Antenatal depression among pregnant mothers in Afghanistan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24, 342. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06548-2 (2024).

Khankhell, R. M. K., Ghotbi, N. & Hemat, S. Factors influencing utilization of postnatal care visits in Afghanistan. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 82, 711 (2020).

Lassi, Z. S., Middleton, P., Bhutta, Z. A. & Crowther, C. Health care seeking for maternal and newborn illnesses in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of observational and qualitative studies. F1000Research 8, 200. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.17828.1 (2019).

Afghanistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2022–2023. https://www.unicef.org/afghanistan/reports/afghanistan-multiple-indicator-cluster-survey-mics-2022-2023.

Tawfiq, E., Saeed, K. M. I., Alawi, S. A. S., Jawaid, J. & Hashimi, S. N. Predictors of mothers’ care seeking behavior for common childhood illnesses: Findings from the Afghanistan health survey 2015. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 12, 7598 (2023).

Tefera, Y., Hailu, S. & Tilahun, R. Early postnatal care service utilization and its determinants among women who gave birth in the last 6 months in Wonago district, South Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2021, 1–9 (2021).

Atuhaire, R., Atuhaire, L. K., Wamala, R. & Nansubuga, E. Interrelationships between early antenatal care, health facility delivery and early postnatal care among women in Uganda: A structural equation analysis. Glob. Health Action 13, 1830463 (2020).

Newbrander, W., Natiq, K., Shahim, S., Hamid, N. & Skena, N. B. Barriers to appropriate care for mothers and infants during the perinatal period in rural Afghanistan: A qualitative assessment. Glob. Public Health 9(Suppl 1), S93-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2013.827735 (2014).

Gebreslassie Gebrehiwot, T. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of early postnatal care service use among mothers who had given birth within the last 12 months in Adigrat town, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, 2018. Int. J. Women’s Health 12, 869–879 (2020).

Stanikzai, M. H., Tawfiq, E., Suwanbamrung, C., Wasiq, A. W. & Wongrith, P. Predictors of antenatal care services utilization by pregnant women in Afghanistan: Evidence from the Afghanistan Health Survey 2018. PLoS One 19, e0309300. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309300 (2024).

Tawfiq, E. et al. Sociodemographic predictors of initiating antenatal care visits by pregnant women during first trimester of pregnancy: Findings from the Afghanistan Health Survey 2018. Int. J. Womens Health 15, 475–485. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijwh.S399544 (2023).

Dona, A., Tulicha, T., Arsicha, A. & Dabaro, D. Factors influencing utilization of early postnatal care services among postpartum women in Yirgalem town, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 10, 20503121221088096 (2022).

Saira, A. et al. Factors associated with non-utilization of postnatal care among newborns in the first 2 days after birth in Pakistan: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Glob. Health Action 14, 1973714 (2021).

Teshale, A. B. et al. Individual and community level factors associated with delayed first postnatal care attendance among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 1–8 (2021).

Khaki, J. Factors associated with the utilization of postnatal care services among Malawian women. Malawi Med. J. 31, 2–11 (2019).

Rahmati, A. Factors associated with postnatal care utilization in Afghanistan. BMC Women’s Health 24, 463. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03318-2 (2024).

Zamawe, C. O., Banda, M. & Dube, A. N. The impact of a community driven mass media campaign on the utilisation of maternal health care services in rural Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 1–8 (2016).

Agho, K. E. et al. Population attributable risk estimates for factors associated with non-use of postnatal care services among women in Nigeria. BMJ Open 6, e010493 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank the UNICEF for allowing us to access and analyze this data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and design: ET and MHS. Analysis: MHS and ET. Writing- original draft: ET and MHS. Writing- review & editing: MHS, ET, AWW, OD. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was reviewed by the Research and Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Kandahar University, Afghanistan. The committee waived the ethical approval because secondary data from the Afghanistan MICS 2022–2023 were used and analysed in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tawfiq, E., Stanikzai, M.H., Wasiq, A.W. et al. Factors influencing early postnatal care use among postpartum women in Afghanistan. Sci Rep 14, 31300 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82750-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82750-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Prelacteal feeding practice and its associated factors in Afghanistan: insights from the 2022–2023 multiple indicator cluster survey

BMC Nutrition (2026)

-

Advancing breastfeeding research in Afghanistan: opportunities for policy and practice

International Breastfeeding Journal (2025)

-

Factors associated with delayed neonatal bathing in Afghanistan: insights from the 2022–2023 multiple indicator cluster survey

BMC Research Notes (2025)

-

Prevalence and associated risk factors of probable PTSD among internally displaced people in Southwest Ethiopia

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Understanding patient perceptions of access to healthcare centers in one of the major cities of Afghanistan

Scientific Reports (2025)