Abstract

Many lipid biomarkers of stroke have been identified, but the lipid metabolism in elderly patients with leukoaraiosis remains poorly understood. This study aims to explore lipid metabolic processes in stroke among leukoaraiosis patients, which could provide valuable insights for guiding future antithrombotic therapy. In a cohort of 215 individuals undergoing MRI, 13 stroke patients were matched with controls, and 48 stroke patients with leukoaraiosis were matched with 40 leukoaraiosis patients. Serum lipidomics was profiled using UPLC-TOF, and OPLS-DA was applied for metabolite identification. Partial Least Squares Path Model (PLS-PM) assessed pathway weights of novel metabolites in stroke risk, while linear regression explored correlations with clinical outcomes. Lipid profiling identified 168 distinct compounds. From these, 25 lipid molecules were associated with glycerolipid, glycerophospholipid, and sphingolipid metabolism. PLS-PM identified 12 key metabolites, including DG 36:4 (OR = 6.40) as a significant risk factor. Metabolites such as PE 38:5 and FA 16:1;O showed significant correlations with stroke in leukoaraiosis, particularly when the Fazekas score was ≥ 4. Twelve metabolites were identified as key factors in stroke incidence among leukoaraiosis patients. Lipid disturbances in glycerolipids and glycerophospholipids provide valuable insights for further studies on the progression from leukoaraiosis to stroke.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leukoaraiosis is manifested as abnormal hyperintense white matter signals in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It is a condition closely related to various factors such as aging and hypertension, and is regarded as an important imaging marker for small vessel diseases1. Leukoaraiosis is tightly associated with stroke, and its significance is manifested in multiple aspects2,3. From the perspective of pathogenesis, it may cause damage to the structure and function of small blood vessels in the brain, thereby interfering with the normal operation of cerebral blood circulation and neurological function4,5,6. This leads to a higher risk of stroke occurrence in patients with leukoaraiosis, and the recovery process after stroke is often more difficult, and the probability of adverse clinical outcomes also increases accordingly. Multiple studies have shown that the risk of stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis is significantly increased, and the functional recovery after stroke is relatively poor with a higher degree of disability7,8,9.

A large number of research findings have provided solid data support for the crucial role of leukoaraiosis in stroke risk. Traylor et al. employed a genetic risk score method to evaluate the impact of gene variants associated with leukoaraiosis on the risk of lacunar stroke10. Their study revealed that genetic factors influencing leukoaraiosis were also correlated with the risk of lacunar infarction, while no significant association was observed with other stroke subtypes10. Arsava et al.'s research found that the severity of leukoaraiosis was closely related to the clinical outcome after ischemic stroke. The more severe the condition, the less satisfactory the functional recovery of the patient after stroke and the more severe the degree of disability2. In addition, studies have shown that the risk of recurrent stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis is significantly increased after a stroke, which fully indicates that leukoaraiosis may act as a persistent risk factor and have an important impact on the recurrence of stroke11.

Our previous research has revealed the great potential of lipidomics and metabolomics in in-depth investigations into the mechanisms of cerebrovascular diseases and the identification of biomarkers. Through lipidomics, we discovered the potential association between carotid artery stenosis induced by radiotherapy and specific triglycerides12. Additionally, metabolomic analysis of cerebral thrombi has highlighted the metabolic differences in thrombi of diverse origins13. Research has shown that modulating glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid metabolism can improve the condition of stroke-induced rats14. Some studies suggest that dyslipidemia may promote the occurrence and development of stroke and leukoaraiosis by affecting multiple biological processes. Dyslipidemia may lead to stroke through mechanisms such as atherosclerosis, thrombosis, inflammation, and cerebrovascular damage6,15. Meanwhile, some studies have found a close relationship between dyslipidemia and leukoaraiosis. A lipidomics-based study has revealed that certain lipid substances are associated with the progression of white matter hyperintensities16. These research results suggest that dyslipidemia may be a common pathological mechanism for stroke and leukoaraiosis17,18,19

In this study, we aim to enhance our understanding of the lipid metabolic processes involved in stroke with leukoaraiosis by utilizing lipidomics techniques to identify key early metabolites. Additionally, we seek to develop early warning signs for stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis, thereby improving clinical guidance and management for this specific patient population.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

A total of 499 patients were enrolled into the database for patients with leukoaraiosis and stroke in leukoaraiosis patients. We selected individuals admitted to Sanming First Hospital Affiliated with Fujian Medical University in China from 2021 to 2022. Patients with severe heart, lung, liver, or kidney diseases; central nervous system tumors; and acute cerebral hemorrhage were specifically excluded. The stroke patients were an acute ischemic stroke patient (onset within 48 h), and they were required to demonstrate no, mild, or severe subcortical white-matter changes on cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and to have no hyperlipidemia or any other conditions that could potentially influence lipid metabolism (Fig. 1A). After applying exclusion criteria, a total of 215 consecutive neurology outpatients and inpatients were included in the study and underwent clinical brain MRI. To create comparable groups and reduce confounding factors, using “matchIt” package of R language, propensity score matching for sex and age was utilized to result in two distinct groups: the leukoaraiosis patients (n = 40) and the stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis (n = 48). A separate control cohort of 100 individuals was also included in the study. The control group was matched with the stroke group based on sex, age, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), glucose levels (GLU), and hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c), resulting in two groups of 13 control individuals and 13 matched stroke patients (Table S1). This retrospective research trial was approved by the Fujian Sanming Hospital ethical committee and registered, and all participants provided written informed consent. The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sanming First Hospital Affiliated with Fujian Medical University (Ethics Approval Number: 2022–44).

Serum lipidome extraction

Blood samples from patients initially hospitalized for leukoaraiosis, stroke with leukoaraiosis or stroke were collected in centrifuge tubes. The fresh blood samples were transported to the laboratory for 20 min by cold chain (4 °C). The serum was isolated by centrifugation at 9000 g at 4 °C for 10 min. The serum samples were stored in − 80 °C freezer. The lipids from serum samples were extracted with isopropanol (IPA). The procedure includes: (1) 200 μL of serum extracted with 600 μL of precooled IPA, (2) vortexed for 1 min, (3) incubated at room temperature for 10 min, (4) storing the extraction mixture overnight at − 20 °C, (5) centrifuged samples at 14,000 rpm for 20 min, (6) transferred the supernatants into a new centrifuge tube and diluted to 1:10 with IPA/ACN/H2O (2.5:1:1, v/v/v). The extracted samples were stored at − 80 °C before the LC/MS analysis. In addition, 50 μL was extracted from each serum sample to prepare a quality control (QC) sample.

LC-QTOF for lipidomics analysis

The samples were analyzed by ACQUITYUPLC (Waters) and XEVO-G2XS quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) mass spectrometry (Waters) with ESI. Lipid separation was performed on an Acquity UPLC charged surface hybrid C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters), and the gradient mobile phase was composed of 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid in an acetonitrile/aqueous solution (A, 60:40, v/v) and 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid in an isopropanol/acetonitrile solution (B, 90:10, v/v). A 20-min accelerated elution curve was employed with the flow rate of the mobile phase 0.4 mL/min. The injected 1 μL sample was initially eluted with 40% B, graded linearly to 43% B in 2 min, and then increased to 50% B in 0.1 min. Over the next 9.9 min, the gradient was further increased to 54% B and then to 70% in 0.1 min. In the last part of the gradient, the amount of B was increased to 99% in 5.9 min. Finally, solution B returned to 40% in 0.1 min, and the column was balanced for 1.9 min before the next injection. The lipids in both positive and negative modes were detected by a Xevo-G2XS QTOF mass spectrometer, which was operated in MSE mode from m/z 50–1200, and the collection time for each scan was 0.2 s. The source temperature was set to 120 ℃. The desolvation temperature was 550 ℃, the gas flow rate was 1000 L/h, and nitrogen was used as the flowing gas. The capillary voltage was set to 2.0 kV (+)/1.5 kV (−), and the cone voltage was 20 V. Leucine encephalin (molecular weight = 555.62 × 200 pg/μL, 1:1 acetonitrile: water) was used as the locking mass for accurate mass determination and corrected with 0.5 mm sodium formate solution. The samples were randomly sorted, and 5 quality control samples were initially injected to adjust the conditions of the column. A QC sample was injected in every 10 samples for analysis to investigate the repeatability of the data. In principal component analysis (PCA), QC samples exhibited tight clustering in the score plot, indicating the stability of the analytical system and consistency of the data. The coefficient of variation (CV) for each lipid in the QC samples was calculated, and lipids with a CV greater than 0.3 were excluded from the dataset. This step ensures that the retained lipids exhibit high analytical reproducibility and reliability.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted on clinical data; gender variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. According to statistical principles for continuous variables, we first determine whether the data follow a normal distribution. If they do, we use the T-test; if they do not, we use the Wilcoxon test.

Metabolic changes in plasma extract were analyzed through a UPLC-Q-TOF MS system in conjunction with the Progenesis QI software (Waters). The original data underwent pre-processing and adjustment using the LOESS linear model, which effectively normalized the data and mitigated the impact of non-uniformity and noise. In the process of lipid molecule selection, a comprehensive evaluation was conducted considering not only the identification score and fragmentation score of each lipid molecule but also its retention time20,21.

Before multivariate statistical analysis, data quality control was performed. In principal component analysis (PCA), QC samples should exhibit tight clustering in the score plot, indicating the stability of the analytical system and consistency of the data. The coefficient of variation (CV) for each lipid in the QC samples was calculated, and lipids with a CV greater than 0.3 were excluded from the dataset. This step ensures that the retained lipids exhibit high analytical reproducibility and reliability.

Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) was first used for classification discrimination. The reliability of the model was verified by cross-validation and displacement test. The parameters R2 and Q2 were used to evaluate the interpretability and predictability of the model, respectively. By p-value (p < 0.05), Variable Importance Projection (VIP ≥ 1) and False Discovery Rate (FDR < 0.05) a standard potential difference marker is selected. The best truncation value was determined by using the Youden index.

In our study, we conducted a metabolite enrichment analysis to identify significant metabolic pathways between two comparison groups, control participates vs. STROKE patients, and leukoaraiosis vs. leukoaraiosis with stroke patients. Significant differential metabolites were identified for each comparison. Each identified metabolite was then mapped to its associated metabolic pathways, noting that a single metabolite might belong to multiple pathways. Using topological algorithms, we calculated the significance of each metabolic pathway based on its proportion of all pathways and the number of metabolites involved. The significance of each pathway in the comparisons was indicated by p-values, with FDR used for p-value correction to reduce false positives. This method assessed the notable differences in metabolic pathways between the groups, providing insights into the biological significance of these pathways22.

Venny was analyzed at the Venny 2.1website(https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/), Sankey diagrams were analyzed at the ChiPlot website (https://www.chiplot.online). Enrichment analyses were analyzed at the metaboanalyst website (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). All statistical analyses, including Partial Least Squares Path Model (PLS-PM), were conducted using R version 4.3.2. PLS-PM is a tool used for Partial Least Squares Path Modeling analysis. This method, a correlation-based Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) algorithm, expresses causal relationships through linear conditional expectations. It aims to identify the best linear predictive relationships and allows the use of latent variables to estimate complex causal relationships or predictive models. Both linear regression and logistic regression models were performed, with p-values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the subjects

We enrolled 499 patients in the database of SanMing First Hospital from 2020 to 2022. Of these, 284 patients were excluded because they did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Among the remaining 215, 99 were further excluded due to medical conditions (Fig. 1A). After propensity matching of sex and age, 40 patients with leukoaraiosis and 48 stroke patients with leukoaraiosis remained for further analysis. The demographics and clinical characteristics of these two groups were summarized in Table 1. Compared to the leukoaraiosis patients, the stroke patients with leukoaraiosis exhibited significant increases in SBP, DBP, GLU, and HBA1c, along with a significant decrease in Fazekas score.

The Fazekas score is a widely used method for visual rating of hyperintense white matter signal abnormalities (WMSA) in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data23,24,25. This scoring system serves as a widely utilized means for gauging the extent of white matter hyperintensity pathologies. The Fazekas score spans a range from 0 to 6, wherein a progressively higher score is indicative of an increasingly severe degree of white matter aberrations25. High Fazekas white matter signal indicates moderate to severe white matter abnormalities (i.e. confluent WMSA, Fazekas score of 4–6), while low Fazekas white matter signal indicates mild white matter abnormalities (i.e. absence or punctate WMSA, Fazekas score of 0–3)26. Based on the Fazekas score26, patients in the leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis were divided into two subgroups (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table 1).

To explore the specificity of key metabolites between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, we also included 13 patients who had suffered stroke (Stroke group) and 13 control participants (Control group). These groups were propensity matched for sex, age, BMI, SBP, DBP, GLU and HBA1c. The demographics and clinical characteristics of the Control and Stroke groups were summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Comparative lipid profiling between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis

To identify key metabolite of stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis, we employed lipidomic profiling to compared serum lipid molecules between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, as well as those in Control and Stroke groups (Fig. S1A-B). Using OPLS-DA, the score plots distinctly displayed the separation between the leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis (Fig. 2A). The results of the permutation test, in which R2 is 0.8, indicating that the model can explain 80% of the variation in the dependent variable, demonstrating the model’s good fitting ability to the data. At the same time, the value of Q2 is 0.3, suggesting that there is still some room for improvement in the model’s predictive ability for the data (Fig. 2B).

Alterations in lipid molecules between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis as well as between Control and Stroke group. (A) OPLS-DA score scatter plot between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis; p1 means covariance of projection-based OPLS-DA model and pcorr1 means correlation of projection-based OPLS-DA model. (B) Permutation test between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. (C) KEGG enrichment analysis of leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. Scatter plots present the enriched metabolic pathways. (D) Venn Analysis: Comparing similarities and differences in lipid molecules among groups. Control vs. Stroke down or up means that lipid molecules exhibit a significant decrease or increase in Stroke compared to Control group. leukoaraiosis patients vs. stroke patients with leukoaraiosis down or up means lipid molecules exhibit a significant decrease or increase in stroke patients with leukoaraiosis compared to leukoaraiosis patients. (E) Sankey Diagram concentrating lipid molecules to metabolic pathways.

Between control and stroke groups, among the 2647 metabolites, 80 different metabolites were selected based on criteria (Supplementary Table 3). Between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, among the 2649 metabolites, 85 different metabolites were selected based on criteria (Supplementary Table 4). The pathways of 80 and 85 different metabolites were documented using KEGG (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). The enrichment analysis of the 80 different metabolites between the Control and Stroke groups was mainly in the Adipocytokine signaling pathway, Glycerophospholipid metabolism, Ether lipid metabolism, and Glycerolipid metabolism (Table 2).

The pathways of 85 different metabolites between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis were primarily enriched in Fat digestion and absorption, Glycerolipid metabolism, Glycerophospholipid metabolism Vitamin digestion and absorption, and Ether lipid metabolism (Fig. 2C and Table 2). Using Venny analysis of differential substances between the Control vs. Stroke and leukoaraiosis patients vs. stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, we identified 77 uniquely differential compounds between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. Notably, Cer 42:1 and Cer 42:2 exhibited a decreasing trend in the Stroke group compared to the Control group, while showing an increasing trend in stroke patients with leukoaraiosis compared to leukoaraiosis patients (Fig. 2D).

Among these 79 (77 + 2) compounds, a Sankey analysis was conducted to further focus on key metabolites in the important pathways. The diagram displayed a concentrated distribution of 25 lipid metabolites to the most enriched pathways, with triglyceride and monoglyceride showing a pronounced tendency to flow towards Glycerolipid metabolism, while phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylcholine predominantly channeled into Glycerophospholipid metabolism, and ceramide followed a distinct trajectory along the Sphingolipid metabolism (Fig. 2E). These 25 lipid molecules have been confirmed as candidate metabolites associated with stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis (Table 3).

Classification of altered lipids between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis

To further investigate the metabolism network and series of alternations in metabolites between the leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, we conducted a classification analysis of lipidhead according to LIPIDMAPS. Compared to the leukoaraiosis patients, there was a significant increase in ceramide, while fatty acid, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidic acid and triglyceride exhibited a significant decrease (Fig. 3A). In the heatmap of altered lipid molecules between the two groups, we observed different clustering of diglycerid, triglyceride, monoglyceride and ceramide, which contributed to distinguishing the stroke patients with leukoaraiosis from leukoaraiosis patients (Fig. 3B). To further investigate the roles of altered metabolites, Partial Least Squares Path Model (PLS-PM) was conducted to provide a deeper understanding of the different lipid classifications with impact and association on outcomes (leukoaraiosis patients or stroke patients with leukoaraiosis). With a modeling goodness of fit (GOF) of 0.785, the results showed that phosphatidylethanolamine and ceramide (r = 0.5085; r = 0.3712 p < 0.001) played significant roles in outcomes (Fig. 3C).

Alternations in lipid classification between leukoaraiosis and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis groups. (A) Lipid skeleton alteration between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. (B) Cluster heat map of changed lipids between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. (C) Customizing structural equation analysis of lipid classifications for the outcome (“Group” in the middle) of leukoaraiosis patients or stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Key metabolites identified based on pathways nodes

A series of lipid molecules, significantly changed between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, were screened based on the enriched pathway nodes of fatty acid elongation, glycerophospholipid, glycerolipid, and sphingomyelin lipid metabolism (Fig. 4A). The numerical values before each lipid names were the loading value calculated by Partial Least Squares Path Model (PLS-PM) based on the framework of phospholipid synthesis pathways in KEGG. Through PLS model loading analysis, we identified compounds with the highest loading value in each pathway node, indicating more important contribution to the outcomes. These metabolites included DG 29:2; DG 36:4; MG 18:1; TG 60:5; FA 16:1;O; LPC 18:3; PC O-19:0; PE 38:4; PE 28:5 LPA 18:1; PI 43:1 and Cer 42:2 (Fig. 4A). Among these 12 metabolites, there were significant increases in MG 18:1, DG 36:4, and Cer 42:2 in the stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, while other lipid compounds exhibited a substantial decrease (Fig. 4B–K).

Screening for the key metabolites for stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. (A) Diagram showing the weights of node molecules in pathway enriched by changed metabolites between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. (B–K) The corresponding key metabolites in stroke patients with leukoaraiosis compared to the leukoaraiosis patients.

Relationships of 12 key metabolites with outcomes

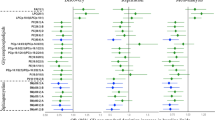

The relationships of 12 metabolites with the outcome were analyzed. The results showed that TG 60:5 exhibited no significant correlation with outcomes, while the other metabolites presented significant correlations (Fig. 5A).

Correlation of 12 key metabolites with the outcomes. (A) Correlation analysis of DG 29:2; DG 36:4; MG 18:1; TG 60:5; FA 16:1;O; LPC 18:3; PC O-19:0; PE 38:4; PE 28:5 LPA 18:1; PI 43:1 and Cer 42:2 with the outcome. (B) Correlation analysis of key metabolites with the outcome under normal or abnormal blood pressure condition. The lower part of the graph represents the scatter plot showing the changes between variables. The numerical values in the upper part display the magnitude of the correlations. The higher the correlation, the larger the “numerical shape”. The significance is indicated by asterisks, with one asterisk (*) denoting a value less than 0.05, two asterisks (**) denoting a value less than 0.01, and three asterisks (***) denoting a value less than 0.001. (C) Multivariable regression analysis for the outcome of stroke with leukoaraiosis incidence using odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values. (D–U) Linear regression was performed for 12 key metabolites and Fazekas score between Control + leukoaraiosis groups (Control/leukoaraiosis) and Control + stroke patients with leukoaraiosis (Control/stroke patients with leukoaraiosis).

Blood pressure has been identified as an independent risk factor for both leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis27. To investigate the relationships between 12 metabolites and outcomes associated with blood pressure, we conducted the correlation analysis of 12 key metabolites with outcomes in normal or abnormal blood pressure conditions. Compared with normal blood pressure, Cer 42:2 and MG 18:1 showed a positive correlation with outcomes in abnormal blood pressure conditions. TG 60:5, FA 16:1;O, LPA 18:1, LPC 18:3, PC O-19:0, PE 38:5 and PI 42:1 exhibited no significant correlation with outcomes in the presence of normal blood pressure. However, in cases of abnormal blood pressure, all these factors demonstrated significant negative correlations (Fig. 5B).

To better elucidate the underlying relationship between the leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, multivariable regression analysis of the 12 key metabolites was conducted. Under the criterion of p-value less than 0.1, four components were marked: DG 36:4, FA 16:1;O, LPA 18:1 and LPC 18:3. Among these, DG 36:4 (OR = 6.40, p = 0.013) was considered as the risk factor (Fig. 5C).

Relationship of 12 key metabolites with Fazekas score between leukoaraiosis and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis

The linear regression analysis was conducted in the group including Control and leukoaraiosis patients as well as the group including Control and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. The results show a significant negative correlation of Fazekas score with DG 29:2, FA 16:1;O, LPC 18:3, MG 18:1, PC O-19:0, PE 38:5, PI 43:1 and TG 60:5 in stroke patients with leukoaraiosis and Control group compared to leukoaraiosis patients and Control group. In contrast, Cer 42:2 and MG 18:1 showed a significant positive correlation (Fig. 5D–U).

Subsequently, we subdivided the patients into two groups by Fazekas score < 4 and Fazekas score ≥ 4. The results of the PLS-PM analysis revealed a positive impact of DG 36:4, MG 18:1 and PI 42:1 on the outcomes (stroke with leukoaraiosis incidence) in both subgroups (Fig. 6A–B). Furthermore, significant correlations were found between MG 18:1, LPA 18:1, LPC 18:3, PC O-19:0, PE 38:4, PI 42:1, and the incidence of stroke with leukoaraiosis when Fazekas score were less than 4. However, these correlations were no longer significant when Fazekas score were 4 or more (Fig. 6C).

Key metabolites for stroke patients with leukoaraiosis in subgroups divided by Fazekas Score. (A–B) Customizing structural equation analysis for the outcomes under Fazekas score less than 4 or more than and equal to 4 conditions. (C) Correlation analysis of key metabolites under Fazekas score less than 4 (upper) or more than and equal to 4 (lower) conditions.

Based on our research findings, the preliminary metabolic processes involved in stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis were formed by the changed pathways in glycerolipid, glycerophospholipid, fatty acid elongation, and sphingolipid (Fig. 7).

Discussion

This study employed a UPLC-MS/MS platform for lipidomic analysis to identify features associated with the occurrence of stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis. Previous investigations have indicated that severe leukoaraiosis could serve as a significant adverse factor affecting early neurological recovery following mechanical thrombectomy (MT), potentially diminishing favorable outcomes in acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients undergoing MT28,29,30. The recent BEST trial demonstrated that moderate to severe leukoaraiosis was linked to poorer outcomes among patients receiving endovascular treatment31. Significant alterations in lipids between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis included glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, and fatty acids (Fig. 3A). Through structural equation modeling and pathway analysis, we selected 12 key metabolites that exhibited excellent performance in distinguishing stroke patients with leukoaraiosis from leukoaraiosis patients (AUC = 0.913) (Fig. S1C).

White matter damage in the brain is often linked to the aging process and chronic conditions such as hypertension, as well as various diseases32. The impact of white matter lesions becomes particularly significant in patients diagnosed with leukoaraiosis, who faced an elevated risk of stroke33. Kongbunkiat et al. conducted a meta-analysis involving 15 studies with a total of 5,967 participants34. They reported a relative risk (RR) of 1.65 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.26–2.16, p = 0.001) for the occurrence of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (SICH) in patients with leukoaraiosis, translating to an absolute risk (AR) increase of 2.5% compared to those without leukoaraiosis34. This consistent association indicates that the presence and severity of leukoaraiosis are linked to a heightened risk of SICH following thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke (AIS). The elevated risk of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) post-thrombolysis in acute cerebral infarction patients with leukoaraiosis may be attributed to factors such as vascular endothelial injury, increased platelet activation, and hypercoagulability34. Additionally, in individuals undergoing anticoagulant treatment, the presence of leukoaraiosis was correlated with an augmented likelihood of recurrent stroke and intracranial hemorrhage35. Nevertheless, conventional risk factors exhibit limitations in fully predicting leukoaraiosis in patients who have experienced a stroke. Lipidomics, an analytical approach focusing on the detection of lipid metabolites at the systemic level, holds promise in uncovering potential biomarkers, identifying lipid metabolic pathways, and constructing networks of lipid metabolism36. A systematic review comprehensively outlined potential metabolic biomarkers and pathways associated with ischemic stroke, underscoring the consistent identification of several metabolites with biomarker potential37. Additionally, metabolomics analysis using machine learning techniques was performed on plasma samples from ischemic stroke patients and controls, revealing three key differential lipid metabolites38. Furthermore, our previous research has identified lipid biomarkers associated with cardioembolic and atherosclerotic stroke14.

Pathway analysis indicated that glycerophospholipid metabolism actively participate in both leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis (Fig. 2C). Concurrently, we observed a significant decrease in glycerophospholipids in the stroke patients with leukoaraiosis (Fig. 3A). Glycerophospholipids are an important part of the neuronal cell membrane structure and are involved in cell recognition and signal transduction. Therefore, the degradation of glycerophospholipids, which produces polyunsaturated fatty acids such as docosahexaenoicacid and arachidonic acid, may be a sign of brain damage39,40. A previous study has indicated that glycerophospholipid metabolism was significantly disrupted in stroke rats. These findings suggest that the decreased levels of glycerophospholipids in the hippocampus may play a role in the pathophysiology of stroke41. Compared to leukoaraiosis patients, a significant decrease in TG in stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, indicating that glycerolipid metabolism may be abnormally suppressed (Fig. 3A).

Through pathway analysis and SCE model, we selected 12 key metabolites between leukoaraiosis patients and stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. We identified these key metabolites to be concentrated in monoglyceride, diglyceride, triglyceride, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, ceramide, and fatty acids. The decreased of TG 60:5 observed in stroke patients with leukoaraiosis compared to leukoaraiosis patients may be associated with an activated inflammatory response (Fig. 4D)42. Our findings suggest that the perturbed equilibrium in triglyceride metabolism could be linked to an inflammatory response. The demyelinating effects of leukoaraiosis impair the network connectivity within the brain to differing extents, influencing specific neurotransmitter conduction pathways in the white matter (WM)43. The preservation of normal cognitive functions is intricately tied to the integrity of the cholinergic pathway in the brain, which forms intricate connections with regions such as the prefrontal cortex, ventral striatum, and hippocampus/amygdala43. Our investigation results also indicated a noteworthy association between the dysregulation of diglyceride, lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), and phosphatidylcholine, and an increased susceptibility to stroke (Fig. 4C and J–K). We also found that higher levels of Cer 42:2 were associated with stroke patients with leukoaraiosis (Fig. 4E). Neuroinflammatory processes, characteristic of demyelinating diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS), contribute to myelin sheath damage44. Previous investigations have demonstrated heightened cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of sphingomyelins and ceramides in individuals with multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating conditions45,46. Based on biological significance, we conducted multivariable regression analysis and identified DG 36:4 (OR = 6.40, p = 0.013) as risk factor for stroke with leukoaraiosis. Concurrently, linear regression analysis revealed that compared to the leukoaraiosis patients vs. Control group, the stroke patients with leukoaraiosis vs. Control group exhibited a significant negative correlation between DG 29:2, FA16:1;O, LPA 18:3, PC O-19:0, PE 38:5, PI43:1 and TG 60:5 and Fazekas scores. We ultimately confirmed the involvement of glycerolipid metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism, and sphingolipid metabolism in the pathway of associated with stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis (Fig. 7).

Potential mechanisms by which leukoaraiosis exacerbates the impact of ischemic stroke encompass hypoxia, vascular endothelial injury, disruption of the blood–brain barrier, and impairment of brain connectivity1. Hypoxia–ischemia is believed to contribute to the etiology of leukoaraiosis47,48. Brain hypoxia primarily arises from small vessel disease, particularly affecting arteries like the thalamostriate and other perforating arteries49,50. Neuropathological investigations have revealed that leukoaraiosis, as observed on CT or MRI scans, correlates with demyelination, astrocytic gliosis, arteriolosclerosis, dilated perivascular spaces, and frequently coexists with lacunar infarcts51. Our previous research found that phosphatidylcholine (PC) significantly decreases under Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy conditions52, while acute ischemic stroke with leukoaraiosis led to decreased PC lipids compared with leukoaraiosis patients (Fig. 7). Acute ischemic stroke is caused by the obstruction of blood supply to the local brain tissue, resulting in ischemic anoxic necrosis, while hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy is caused by insufficient blood supply to the whole body or brain. The same decreased PCs indicate the potential similar mechanism of lipid disturbance in the processes between acute ischemic stroke and hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy.

Some studies discovered significant blood–brain barrier leakage in the normal white matter of stroke patients, which became more severe the closer to areas of white matter hyperintensity (WMHs). Additionally, blood–brain barrier dysfunction worsens with increasing WMH load53,54. Logistic regression analysis revealed that, in cases with lower Fazekas score, 12 compounds have high predictive value for stroke patients with leukoaraiosis (Fig. S1D-E). Other studies have confirmed the significant role of plasma Cer(24:1) concentration in predicting referrals for coronary angiography in different populations55,56. These results indicated a notable association between elevated plasma sphingolipid concentrations and adverse cardiovascular events55,56. Harshfield’s investigation had revealed a positive correlation between higher levels of SM(d18:2/24:1) and measures such as fissure count, WMH volume, and cognitive abilities57. Our study further substantiated a significant elevation in Cer 42:2 as well as Cer(18:1/24:1) within the stroke patients with leukoaraiosis, regardless of the Fazekas scores < 4 or ≥ 4.

Leukoaraiosis patients with acute cerebral infarction share common risk factors, including advanced age, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and alcohol consumption1. With the exception of age, which cannot be controlled, targeting the aforementioned risk factors is of paramount importance for both primary and secondary prevention strategies. Our study, through an in-depth exploration of metabolic biological processes, provides a theoretical basis and assistance for the future prevention and treatment from leukoaraiosis to stroke patients with leukoaraiosis. However, this study has some limitations. The current validation is limited to self-validation, and further studies are needed to validate and optimize the discovered biomarkers and evaluate their effectiveness in terms of clinical application. Therefore, in future studies, we should select purer samples and expand the sample size to further investigate the biomarkers of these findings and evaluate their clinical applicability in screening and diagnosing stroke in individuals and patients with leukoaraiosis. This will contribute to the improvement of screening and diagnostic methods for individuals with leukoaraiosis and stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis, enabling clinicians to develop more personalized treatment strategies.

Conclusion

This study identified 12 novel metabolites as potential key metabolites for stroke incidence in patients with leukoaraiosis, spanning various Fazekas score subgroups. The research provides new insights into potential mechanisms that underlie the transition from leukoaraiosis to stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis, with a focus on disruptions in glycolipids and glycerophospholipids. Additionally, the study highlights the regulatory role of Cer 42:2 as well as Cer(18:1/24:1). These findings offer a comprehensive foundation for further investigations into the mechanistic intricacies of stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis.

Data availability

The article and supplementary material contain the original contributions discussed in this study; further questions should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- CHOL:

-

Cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- GLU:

-

Glucose

- HCY:

-

Homocysteine

- HBA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

- Cer:

-

Ceramide

- DG:

-

Diglyceride

- MG:

-

Monoglyceride

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- FA:

-

Fatty acid

- LPA:

-

Lysophosphatidic acid

- LPC:

-

Lysophosphatidylcholine

- PC:

-

Phosphatidylcholine

- PE:

-

Phosphatidylethanolamine

- PI:

-

Phosphatidylinositol

- Cer 42:1:

-

Cer(d18:0/24:1)

- Cer 42:2:

-

Cer(d18:1/24:1)

- DG 29:2:

-

DG(12:0/17:2/0:0)

- DG 31:2:

-

DG(14:0/17:2/0:0)

- DG 36:4:

-

DG(14:0/22:4/0:0)

- DG O-38:8:

-

1-(6-3-Ladderane-hexanoyl)-2-(8-3-ladderane-octanyl)-sn-glycerol

- MG 18:1:

-

MG(0:0/18:1/0:0)

- MG 20:4:

-

1-Arachidonoyl-sn-glycerol

- TG 60:5:

-

TG(18:3/20:1/22:1)

- FA 16:1;O:

-

16-Hydroxy-6-hexadecenoic acid

- FA 21:3;O:

-

10-(3,4-Dimethyl-5-pentylfuran-2-yl)-decanoic acid

- FA 27:2;O:

-

(5Z,9Z)-2-methoxy-hexacosadienoic acid

- FA 29:4:

-

23-Phenyl tricosanoic acid

- FA 34:0;O:

-

Hydroxyphthioceranic acid (C34)

- LPA 18:1:

-

Lysophosphatidic acid

- LPC 18:3:

-

PC(18:3/0:0)

- PC 44:12:

-

PC(22:6/22:6)

- PC O-19:0:

-

PC(O-18:0/1:0)

- PE 38:4:

-

PE(20:4/18:0)

- PE 38:5:

-

PE(20:2/18:3)

- PE 38:6:

-

PE(22:6/16:0)

- PE dO-40:0:

-

Beta-hydroarchaetidylethanolamine

- PE O-40:4:

-

PE(O-18:0/22:4)

- PI 36:3:

-

PI(20:2/16:1)

- PI 43:1:

-

PI(22:1/21:0)

- CK:

-

Control group

References

Tang, X. et al. Leukoaraiosis and acute ischemic stroke. Eur. J. Neurosci. 54, 6202–6213 (2021).

Arsava, E. M. et al. Severity of leukoaraiosis correlates with clinical outcome after ischemic stroke. Neurology 72, 1403–1410 (2009).

Curtze, S. et al. Cerebral computed tomography-graded white matter lesions are associated with worse outcome after thrombolysis in patients with stroke. Stroke 46, 1554–1560 (2015).

Epstein, A. et al. Chronic covert brain infarctions and white matter hyperintensities in patients with stroke, transient ischemic attack, and stroke mimic. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e024191 (2022).

Ryu, W. S. et al. Grading and interpretation of white matter hyperintensities using statistical maps. Stroke 45, 3567–3575 (2014).

Zhao, W. et al. Association of lipid profiles and the ratios with arterial stiffness in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Lipids Health Dis. 13, 37 (2014).

Taylor, S. S. et al. Cognitive mediators of change in physical functioning in response to a multifaceted intervention for managing osteoarthritis. Int. J. Behav. Med. 25, 162–170 (2018).

van Harten, B., de Leeuw, F. E., Weinstein, H. C., Scheltens, P. & Biessels, G. J. Brain imaging in patients with diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Care 29, 2539–2548 (2006).

Carballo, J. A., Pincheira, J. & de la Torre, C. The G2 checkpoint activated by DNA damage does not prevent genome instability in plant cells. Biol. Res. 39, 331–340 (2006).

Traylor, M. et al. Genetic associations with white matter hyperintensities confer risk of lacunar stroke. Stroke 47, 1174–1179 (2016).

Quehenberger, O. et al. Lipidomics reveals a remarkable diversity of lipids in human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 51, 3299–3305 (2010).

Li, W. et al. Distinct lipid profiles of radiation-induced carotid plaques from atherosclerotic carotid plaques revealed by UPLC-QTOF-MS and DESI-MSI. Radiother. Oncol. 167, 25–33 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Thrombosis origin identification of cardioembolism and large artery atherosclerosis by distinct metabolites. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 15, 701–707 (2023).

Sun, J. et al. Neuroprotective effects of Longxue Tongluo Capsule on ischemic stroke rats revealed by LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics approach. Chin. Herb. Med. 15, 430–438 (2023).

Grassi, D. et al. Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction: Say NO to cigarette smoking!. Curr. Pharm. Des. 16, 2539–2550 (2010).

Wang, G. et al. Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol predicts adverse outcomes in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 52, 2035–2042 (2021).

Adams, H. P. Jr. et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke 24, 35–41 (1993).

Kimura, L. F. et al. COVID-19 induces proatherogenic alterations in moderate to severe non-comorbid patients: A single-center observational study. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 92, 102604 (2021).

Andreassen, O. A. et al. Improved detection of common variants associated with schizophrenia by leveraging pleiotropy with cardiovascular-disease risk factors. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 197–209 (2013).

Choi, J. M., Kim, T. E., Cho, J. Y., Lee, H. J. & Jung, B. H. Development of lipidomic platform and phosphatidylcholine retention time index for lipid profiling of rosuvastatin treated human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 944, 157–165 (2014).

Dunn, W. B. et al. Procedures for large-scale metabolic profiling of serum and plasma using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 6, 1060–1083 (2011).

Ewald, J. D. et al. Web-based multi-omics integration using the Analyst software suite. Nat. Protoc. 19, 1467–1497 (2024).

Fazekas, F., Chawluk, J. B., Alavi, A., Hurtig, H. I. & Zimmerman, R. A. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 149, 351–356 (1987).

Olsson, E. et al. White matter lesion assessment in patients with cognitive impairment and healthy controls: Reliability comparisons between visual rating, a manual, and an automatic volumetrical MRI method-the gothenburg MCI study. J. Aging Res. 2013, 198471 (2013).

Wardlaw, J. M. et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 12, 822–838 (2013).

Hilal, S. et al. Prevalence, risk factors and consequences of cerebral small vessel diseases: Data from three Asian countries. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 88, 669–674 (2017).

Zeng, J. et al. Plasma lipidomic profiling reveals six candidate biomarkers for the prediction of incident stroke in patients with hypertension. Metabolomics 20, 13 (2024).

Guo, Y. et al. Safety and efficacy of early antiplatelet therapy in acute ischemic stroke patients receiving endovascular treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 66, 45–50 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. Leukoaraiosis severity and outcomes after mechanical thrombectomy with stent-retriever devices in acute ischemic stroke. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 11, 137–140 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. Leukoaraiosis and earlier neurological outcome after mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. J. Neuroradiol. 47, 428–432 (2020).

Mistry, E. A. et al. White matter disease and outcomes of mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 41, 639–644 (2020).

Lee, W. J. et al. Periodicity of cerebral flow velocity during sleep and its association with white-matter hyperintensity volume. Sci. Rep. 9, 15510 (2019).

Gottesman, R. F. & Hillis, A. E. Predictors and assessment of cognitive dysfunction resulting from ischaemic stroke. Lancet Neurol. 9, 895–905 (2010).

Kongbunkiat, K. et al. Leukoaraiosis, intracerebral hemorrhage, and functional outcome after acute stroke thrombolysis. Neurology 88, 638–645 (2017).

Dimaras, T. et al. Leukoaraiosis as a promising biomarker of stroke recurrence among stroke survivors: A systematic review. Neurol. Int. 15, 994–1013 (2023).

Giles, C., Takechi, R., Lam, V., Dhaliwal, S. S. & Mamo, J. C. L. Contemporary lipidomic analytics: Opportunities and pitfalls. Prog. Lipid Res. 71, 86–100 (2018).

Ke, C., Pan, C. W., Zhang, Y., Zhu, X. & Zhang, Y. Metabolomics facilitates the discovery of metabolic biomarkers and pathways for ischemic stroke: A systematic review. Metabolomics 15, 152 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. Identification of three potential novel biomarkers for early diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke via plasma lipidomics. Metabolomics 19, 32 (2023).

Yoon, C. W. et al. Is antiplatelet treatment effective at attenuating the progression of white matter hyperintensities?. PLoS One 12, e0176300 (2017).

Zhou, W. et al. Early warning of ischemic stroke based on atherosclerosis index combined with serum markers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107, 1956–1964 (2022).

Jiang, W. et al. Alteration of glycerophospholipid metabolism in hippocampus of post-stroke depression rats. Neurochem. Res. 47, 2052–2063 (2022).

Nordestgaard, B. G. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: New insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. Circ. Res. 118, 547–563 (2016).

Lim, J. S., Kwon, H. M. & Lee, Y. S. Effect of cholinergic pathway disruption on cortical and subcortical volumes in subcortical vascular cognitive impairment. Eur. J. Neurol. 27, 210–212 (2020).

Rosenberg, G. A. Inflammation and white matter damage in vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke 40, S20-23 (2009).

Checa, A. et al. Hexosylceramides as intrathecal markers of worsening disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 21, 1271–1279 (2015).

Capodivento, G. et al. CSF sphingomyelin: A new biomarker of demyelination in the diagnosis and management of CIDP and GBS. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 92, 303–310 (2021).

Brickman, A. M. et al. Cerebral autoregulation, beta amyloid, and white matter hyperintensities are interrelated. Neurosci. Lett. 592, 54–58 (2015).

O’Sullivan, M. et al. Patterns of cerebral blood flow reduction in patients with ischemic leukoaraiosis. Neurology 59, 321–326 (2002).

Shim, Y. S. et al. Pathological correlates of white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 39, 92–104 (2015).

Szolnoki, Z. Pathomechanism of leukoaraiosis: A molecular bridge between the genetic, biochemical, and clinical processes (a mitochondrial hypothesis). Neuromol. Med. 9, 21–33 (2007).

Awad, I. A., Johnson, P. C., Spetzler, R. F. & Hodak, J. A. Incidental subcortical lesions identified on magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly. II. Postmortem pathological correlations. Stroke 17, 1090–1097 (1986).

Chen, X. et al. Lipidomics reveal the cognitive improvement effects of Acer truncatum Bunge seed oil on hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy rats. Food Funct. 14, 6610–6623 (2023).

Munoz Maniega, S. et al. Integrity of normal-appearing white matter: Influence of age, visible lesion burden and hypertension in patients with small-vessel disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 37, 644–656 (2017).

Wardlaw, J. M. et al. Blood-brain barrier permeability and long-term clinical and imaging outcomes in cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke 44, 525–527 (2013).

Meeusen, J. W. et al. Plasma ceramides. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 38, 1933–1939 (2018).

Laaksonen, R. et al. Plasma ceramides predict cardiovascular death in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes beyond LDL-cholesterol. Eur. Heart J. 37, 1967–1976 (2016).

Harshfield, E. L. et al. Metabolomic profiling in small vessel disease identifies multiple associations with disease severity. Brain 145, 2461–2471 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the technical staff and Dr. Shufeng Li at Beijing Hexin Technology Co., Ltd. for their invaluable assistance with the untargeted metabolomics analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fujian Sanming Science and Technological innovation Project: Screening of novel lipid markers for cerebral infarction in patients with leukoaraiosis and construction of prediction model [grant numbers NO: 2023-S-70], and Fujian Provincial Science and Technology Project: Nervonic acid intervenes in the Process of Alzheimer’s disease by regulating the intestinal flora and metabolism [grant number 2020J011271].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lin Feng and Song Yige: Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. Cao Hongli : Editing. Fengye Liao and Yanping Deng: Visualization, Investigation. Qinyu Wei and Weimin Hong: Software, Validation. Guifeng Yao and Chunguang Ding: Methodology, Software. Chen Xianyang: Conceptualization, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sanming First Hospital Affiliated with Fujian Medical University (Ethics Approval Number: 2022–44). The participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Before participating in the study, all participants signed up with informed permission.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, F., Song, Y., Cao, H. et al. Serum lipid profiling reveals characteristic lipid signatures associated with stroke in patients with leukoaraiosis. Sci Rep 14, 31337 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82808-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82808-7