Abstract

The CRTS (China Railway Track System) II slab ballastless track is widely utilized in high-speed railway construction owing to its excellent structural integrity. However, its interfacial performance deteriorates under high-temperature conditions, leading to significant damage in structural details. Furthermore, the evolution of its performance under these conditions has not been comprehensively studied. In this study, a bilinear cohesive damage model was developed using positive tensile and push-out model tests to describe the interfacial mechanical behavior of the track structure. A three-dimensional refined numerical simulation model of the CRTS II slab ballastless track was developed and validated using existing test data to analyze the distribution of structural damage and its evolution under varying temperature conditions. The results demonstrate that the proposed bilinear cohesive damage model effectively characterizes the interlayer damage evolution in the track structure. As the overall temperature increases, interlayer separation initiates at the wide-narrow joints and propagates from the slab ends toward the center. At a temperature rise of 60 °C, the interface becomes fully separated, and the vertical displacement of the wide-narrow joints and the track slab reaches 1.09 cm. The middle and end sections of the wide joints are particularly susceptible to compressive damage, with the top section being more sensitive to temperature changes. These results provide critical insights into the damage mechanisms and performance evolution of ballastless tracks under thermal loading, offering a foundation for improved design and maintenance strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

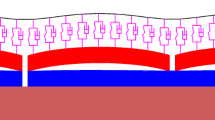

By the end of 2023, the mileage of China’s high-speed railroad has exceeded 40,000 km. The CRTS II slab ballastless track is a longitudinally integrated track system known for its excellent integrity, enabling continuous ballastless track laying across girder joints1. It is widely utilized in major rail projects such as the Beijing-Shanghai High-speed Railway, Shanghai-Kunming High-speed Railway, Beijing-Tianjin Intercity Railway, and Ning-Hangzhou Passenger Dedicated Railway2,3,4. It consists of a multilayered, heterogeneous structure primarily comprising track slabs, a CA mortar layer, and a concrete base. To form a continuous longitudinal structure and ensure overall structural integrity, wide-narrow joints are utilized between adjacent track slabs, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The CRTS II slab ballastless track features a multilayered heterogeneous structure, primarily comprising track slabs, a CA mortar layer, and a concrete base. Additionally, the wide-narrow joint is employed between adjacent track slabs to form a continuous longitudinal structure, thereby ensuring the overall structural integrity, as shown in Fig. 1. Current research on ballastless track structures has focused on comprehensive studies through theoretical analysis, experimental research, and numerical simulations. Lou et al.5, Wang et al.6, and Chen7 conducted theoretical analyses to investigate the temperature field and thermal effects on ballastless tracks. Their research established a mapping relationship between environmental conditions and the temperature values of the track structure, which facilitated the calculation of the heat conduction equation. Wang et al.8 developed a simulation model of the track temperature field using hourly meteorological data, accounting for track orientation and geographic location. Furthermore, Yusupov et al.9 developed a three-dimensional finite element coupling model based on coupled dynamics theory, indicating that structural acceleration increases with rising temperature. This study pioneered an exploration of the dynamic response of temperature on track structure, providing a reference for improving track dynamics. Comprehensive indoor and on-site tests have also examined the temperature stress variation laws10,11,12, cumulative settlement13, static performance14,15, and time-dependent mechanical properties16,17,18,19 of ballastless tracks.

Numerous insights have emerged from the aforementioned research, primarily focusing on the track structure system, providing a robust theoretical foundation for the design and maintenance of track structures. However, in actual service conditions, high-temperature loading often results in uncoordinated interlayer deformation and significant axial forces within the structure. This typically manifests as interlayer separation between the track slab and CA mortar (Fig. 2a), as well as wide-narrow joint breakage (Fig. 2b), ultimately disrupting the structural force transfer mechanism and reducing structural stability. Consequently, exploring the mechanisms of interlayer interface and joint damage evolution holds significant research value to ensure the safe operation of high-speed railways. Building on these findings, scholars have conducted push plate tests on enhanced full-scale CRTS II slab track structures in both longitudinal and transverse directions. These tests yielded the load–displacement relationship at the interface between the track slab and the CA mortar layer20,21,22 and calibrated the interfacial adhesion parameters based on the test results.

However, the interface damage modes are generally classified into tension, shear, and tearing. Since tearing and shearing are essentially shear stresses, the interface damage modes can be classified into tension and shear damage. Calibrating the interfacial tensile bonding parameters using the full-scale model is challenging. Researchers conducted splitting and shear tests on small specimens to systematically characterize interface damage behavior. Du et al.23 and He et al.24 conducted splitting tensile and shear tests on composite specimens of track slab and SCC to obtain the variations in interface tension and displacement in CRTS III slab ballastless tracks. Wang et al.25 performed indoor tests on interlayer normal and tangential cracking of interlayer bonded structural members in double-block ballastless tracks and analyzed interlayer damage behavior and intrinsic parameters. For CRTS II slab ballastless tracks, Su et al.26 conducted split-shear modeling tests on composite specimens to determine the interfacial parameters between the track slab and the CA mortar layer, using digital image correlation (DIC) to obtain the stress-displacement relationship. Xu et al.27 derived the constitutive relationship of the interface for debonding and repairing through split-shear tests, to evaluate the effects of debonding and repairing on the mechanical properties of CRTS II slab ballastless tracks, and subsequently analyzed the mechanical behavior and constitutive parameters of the debonding and repairing interface. The ontological relationship of the repaired interface was obtained through splitting and shear tests to describe the interface behavior post-repair. Notably, comparisons between small specimen models and full-scale models revealed a size effect, as measured parameters exhibited variability. To address this, Liu et al.28 proposed a linear proportional distribution method to describe the force–displacement variation rule in push slab tests across different damage stages, verifying the feasibility of scaled push slab tests for determining cohesion parameters.

On the other hand, regarding the damage mechanisms of wide-narrow joints of track structure, Cai et al.29 integrated field research to examine the damage progression of concrete joints and its impact on structural stability. Li et al.30 developed a three-dimensional finite element model of CRTS II slab ballastless track, considering varying degrees of joint defects, and investigated the impact of these defects on the initiation of interface damage and temperature increase. Based on the concrete plasticity damage model and cohesion model, Liu et al.31. studied the damage evolution and development mechanisms of wide-narrow joints and proposed strategies to mitigate damage. In addition, Zhou et al.32 identified six interface damage modes through on-site investigations of track structures, analyzed the thermal behavior of detailed structures at varying temperatures and damage levels and concluded that overall temperature amplitude has a greater impact on structural stability than temperature gradient. Although the aforementioned studies have yielded significant insights into the damage evolution of wide-narrow joints, the heterogeneous nature of these joints necessitates further investigation into the damage processes and distribution of structural details.

In summary, this paper aims to investigate the interfacial mechanical properties of the CRTS II slab ballastless track and the evolution of structural details damage. To minimize the size effect on interlayer cohesion parameters, vertical full-scale tensile and push-out model tests will be conducted. DIC will be employed to obtain the interface stress-displacement relationship, providing intrinsic parameters to describe interface damage behavior. Additionally, a concrete plastic damage model will be introduced, and a three-dimensional refined numerical simulation model of the track structure will be developed by integrating the interface Cohesive Zone Model (CZM). The simulation will be validated using previous experimental results. Lastly, this study will investigate structural deformation, the evolution of interlayer interface damage, and the damage distribution at wide-narrow joints under elevated summer temperature conditions.

Research significance

This study provides a comprehensive and in-depth investigation of the damage evolution between layers and slabs of the CRTS II slab ballastless track structure under high-temperature conditions in summer, advancing beyond the scope of previous research. While earlier studies calibrated the cohesive parameters of the track slab-CA mortar interlayer interface, this study developed a vertical full-scale model to conduct further experimental investigations, mitigating the variability caused by the size effect in smaller specimen models. Additionally, the Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) model and the CZM were employed to create a refined three-dimensional numerical simulation. This model was compared and validated against existing experimental results, providing a reliable tool for investigating structural deformation, and the evolution of interlayer and interplate damage under varying temperature conditions. Furthermore, by analyzing damage distribution at different locations of interlayer and interplate joints, the study identifies the most vulnerable areas, providing theoretical insights to aid researchers and engineers in designing and maintaining track structures.

Experimental program

Specimen design and manufacture

Current research predominantly emphasizes push-out tests, with limited attention to positive tensile tests, most of which have been conducted by institutions such as Southwest Jiaotong University, the Institute of Railway Science, and Central South University. To address this gap, the present study performs both push-out and tensile tests to investigate the evolution of interfacial properties between the track slab and the CA mortar layer in ballastless track systems. In earlier studies, small specimen clipping tests (150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm) were used to assess interfacial properties, from which interfacial cohesion parameters were derived. However, statistical analysis revealed inconsistencies in the cohesion parameters reported by earlier researchers. Therefore, to more accurately determine the interfacial adhesion performance of ballastless tracks under real service conditions, this study adjusts the vertical dimension of the specimen to align with field conditions, as shown in Fig. 3.

The fabrication of composite specimens follows the actual construction process of the CRTS II slab ballastless track, with temperature sensors pre-embedded during specific steps. The process includes the following steps: (i) A mold was prepared according to the specimen dimensions, and reinforcement cages for the track slab and concrete base are positioned within the mold, as depicted in Fig. 4a. (ii) Concrete was poured based on the designated mix design. After the initial setting, brush the surface and allow it to cure naturally outdoors for 28 days, as shown in Fig. 4b. (iii) Following natural curing, assemble the track slab and concrete base with a 30 mm interlayer gap. Seal the slab edges with plastic sheeting, leaving small holes to verify complete CA mortar filling, as illustrated in Fig. 4c. (iv) The CA mortar was poured and cured for 28 days, as shown in Fig. 4d.

Loading system

The load application device used in this study was a hydraulic jack with a capacity of 200 kN. The push-out test fixture is shown in Fig. 5a. The jack was used to apply longitudinal thrust to the track slab, while the concrete base was secured by ground anchors. A counterforce wall was employed to support and evenly distribute the load until shear damage occurred at the CA mortar interface. The setup for the positive tensile test is illustrated in Fig. 5b. A double-spliced channel steel beam served as the primary load-bearing member, transferring the load to the mat column. Once the concrete base was anchored, the jack was pushed against a steel plate to apply the load. The tensile force was then transmitted to the track slab’s pin bar via the screw connector, applying a positive tensile force to the specimen until tensile damage occurred at the CA mortar interface.

Testing method

In this study, the DIC was employed to monitor interface parameters, including displacement and strain. DIC is an optical measurement technique used to assess surface deformation in objects. The method involves capturing two digital speckle images of the specimen in its undeformed and deformed states. A region in the pre-deformation image is defined as the reference sub-area, while the corresponding region in the post-deformation image is designated as the target sub-area. Through computational analysis, a one-to-one correspondence between the reference sub-area and the target sub-area is established to extract displacement and deformation data. The positional disparity between the reference sub-area and the target sub-area reflects the displacement component, while the geometric distortion reflects the strain component. The basic principle of DIC is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Interfacial bond-slip response

The composite specimens for the positive tensile and push-out tests were segmented into regions along the interlayer interface, as shown in Fig. 7. To reduce the influence of end defects on interface stress, the first region, S1, was positioned 15 mm from the slab edge. From S1, subsequent regions were spaced at intervals of 70 mm along the x-axis and designated as S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, and S7. Similarly, the push-out specimen was segmented into regions labeled T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, and T7. It should be noted that the DIC test results provide only the strain and displacement fields of the interface. Therefore, previous researchers have employed generalized Hooke’s law to estimate stress values at the interface test points. This study adopts a similar method to convert the strain values at the track slab-CA mortar interface into stress values33.

For the positive tensile composite specimen, observation points 1 and 1′ were selected at the interface test points, located near the interface crack and symmetrically arranged to ensure precise relative displacement measurements. The strain and displacement values at points 1 and 1′ were analyzed based on DIC data obtained earlier. The displacement over time at points 1 and 1′ were denoted as μ1(t) and μ1′(t), respectively. The horizontal and vertical strain changes over time at point 1 were represented as ε1x(t) and ε1y(t). From these values, the normal relative displacement of the track slab-CA mortar interface, referred to as the normal separation displacement δI(t), can be calculated, as expressed in Eq. (1).

Based on generalized Hooke’s law, the value of horizontal stress at observation point 1 can be determined as shown in Eq. (2).

where v is Poisson’s ratio and E is elastic modulus. That is, the interface normal bonding stress σI = σ1x(t).

The normal separation displacements in the regions from Z1 to Z7, as well as the interface normal bonding stress, were computed based on the equations provided above.

For the push-out composite specimen, observation points 1 and 1′ were similarly selected at the interface test points, situated near the interface crack and symmetrically arranged about it to ensure precise relative displacement measurements. The strain and displacement values at points 1 and 1′ were analyzed based on DIC data obtained earlier. The displacement changes over time at points 1 and 1′ were denoted as κ1(t) and κ1′(t), respectively, while the tangential strain change over time at point 1 is defined as γ1(t). From these values, the tangential relative displacement of the track slab-CA mortar interface, referred to as the tangential separation displacement δII(t), can be calculated, as expressed in Eq. (3).

Based on the generalized Hooke’s law the value of shear stress at observation point 1 can be obtained as in Eq. (4).

where, G is the shear modulus, \(G = E/\left[ {2(1 + v)} \right]\), interfacial tangential bonding stress σII = τ1(t).

The tangential separation displacements in the regions T1 through T7, as well as the tangential bonding stresses at the interface, can be calculated using the aforementioned equations.

The interfacial stresses and relative separation displacements at the interlayer were calculated using the previously described method, enabling the derivation of key parameters for various regions. Values measured via DIC were computed using Eqs. (1) to (4) for both the positive tensile composite specimen and the push-out composite specimen. The derived parameters were plotted to generate the interfacial bond-slip response curves in both the normal and tangential directions. Based on the scatter plots, the least squares method was applied to fit the curves for the elastic stage and the damage evolution stage. The inflection point, marking the transition from the elastic stage to the damage evolution stage, was identified as the splitting point, as shown in Fig. 8.

Through this method, the damage onset displacement δ0, damage failure displacement δf, damage onset stress tmax, interface stiffness K, and fracture energy GC in the CZM model are determined, as shown in Table 1.

Finite element simulation

Bilinear cohesive zone model

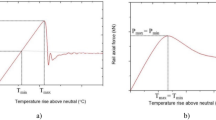

The bilinear cohesive zone model primarily describes the mechanical behavior in the thickness direction and the perpendicular direction. This bilinear constitutive model is illustrated in Fig. 9. It characterizes the bonded layer’s force response under tension and shear, with the vertical axis indicating traction force and the horizontal axis representing separation displacement. The traction-displacement constitutive relationship consists of two phases: a linear elastic phase and a damage evolution phase. Initially, the interface separation displacement increases linearly with the traction force, depicting the initial stiffness of the interface. Once the separation displacement reaches the damage onset displacement, the corresponding traction force reaches its peak, and the interface stiffness begins to degrade. Following this, the interface enters the damage evolution phase until the separation displacement reaches the failure displacement, culminating in the complete mechanical response.

The control equations for the above bilinear cohesion model are as follows34:

where, i = n,s,t represent the normal, first shear direction and second shear direction, respectively, Kii is the initial slope, δi is the interfacial separation displacement, \(\delta_{i}^{0}\) is the damage initiation displacement and \(\delta_{i}^{f}\) is the damage failure displacement. Notably, a damage factor Di is introduced to characterize the stage of damage evolution, as shown in Eq. (5).

Interlayer interface damage is not limited to unidirectional cases, such as pure tensile or pure shear modes. Instead, interlayer damage exhibits complex mechanical behavior, often involving mixed Type I/II/III damage. In the mixed stress mode, the interface experiences simultaneous tensile and shear stresses. To simplify the calculation, it is necessary to integrate the mechanical behaviors of tension and shear into a unified bilinear cohesive model35. This model comprises a linear elastic rising stage, a damage evolution descending stage, and a complete failure stage, as illustrated in Fig. 10.

The strength criterion defines the transition threshold of the interface from the linear elastic phase to the damage evolution phase. This criterion is categorized into two types: strain criteria and stress criteria. These are further subdivided into the maximum nominal strain criterion, maximum nominal stress criterion, secondary nominal strain criterion, and secondary nominal stress criterion, as expressed in Eq. (7). Displacement measurement poses greater challenges during testing, making the strain criterion less commonly employed.

where, \(t_{n}^{max}\), \(t_{s(t)}^{max}\) are the ultimate bearing stress in the interface normal and shear direction separately, i.e. the damage initiation stress. \(\varepsilon_n^{0}\), \(\varepsilon_{s(t)}^{0}\), \(\varepsilon_{t}^{0}\) are the damage initiation strain in the interface normal and shear direction respectively. In addition, < > indicates that the item will not cause interface damage under the interface normal pressure condition, i.e., the normal stress is not considered as compressive stress.

To describe the damage evolution process in the mixed mode, an equivalent displacement δm is introduced for this, as shown in Eq. (8).

The damage factor of Eq. (6) can be transformed into Eq. (7).

It can be determined based on the critical fracture energy, and the interface fails when the energy release rate is greater than the critical fracture energy, as shown in Eq. (10).

where, Gn, Gs and Gt are the type I, II and III energies released at the interface end during the damage evolution process, GC is the fracture energy, GS is the sum of type II and III energies released at the interface end during the damage evolution process, GT is the sum of type I, II and III energies released at the interface end during the damage evolution process, and η is the material coefficient.

Damaged plasticity theory of concrete

To obtain the damage evolution of wide and narrow joints under axial loading, the CDP model was employed. The most widely used methods for calculating the damage factor in the CDP model include the energy equivalence method36, Fang-Zihu method37, and Birtel method38. A comparative analysis identified the Fang-Zihu method as optimal for calculating the principal plasticity parameters of wide-narrow joints, as illustrated in Fig. 11.

The 3D simulation model of CRTS II slab ballastless track

Ballastless track numerical simulation modeling

Based on relevant on-site construction data, the three-dimensional nonlinear numerical simulation model of the ballastless track is composed of the track slab, wide-narrow joint, CA mortar layer, steel reinforcement, and concrete base. The steel rail was excluded to simplify the structural analysis. To mitigate boundary effects, the simulation model includes five track slabs, as shown in Fig. 12. The material properties used in the model are listed in Table 2. To accurately reflect the functional characteristics and interactions between the layers of the track structure, the precast track slab, CA mortar layer, concrete base, and wide-narrow joint were simulated using the C3D8R solid element, resulting in a total of 201,148 solid elements and 302,356 nodes.

To ensure accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency, a mesh convergence study was conducted. In this study, the mesh size in critical regions, such as the wide-narrow joint and the interface between the track slab and CA mortar layer, was systematically refined, while less critical regions used coarser meshes. The results indicate that reducing the mesh size below 5 mm in critical regions led to negligible changes in stress and displacement values, suggesting that further refinement would not significantly improve accuracy. Consequently, a mesh size of 5 mm was adopted for these regions to balance computational cost and precision. The convergence analysis demonstrated that the selected mesh size is sufficient to capture the damage evolution and interfacial behavior with high fidelity. This mesh scheme ensures the robustness of the numerical model and provides reliable results for the structural analysis under thermal loading conditions.

To investigate the wide-narrow joint and the damage between the track slab and the CA mortar layer, the CZM was applied to the interfaces between the bottom surfaces of the track slab and the narrow joint and the mortar layer to simulate the nonlinear traction–separation behavior at these interfaces. The damage model for the track slab and CA mortar layer used the CZM constitutive model discussed in the previous section to examine interface damage behavior. The wide-narrow joint and the track slab primarily act as interfaces between old and new concrete, exhibiting significant variability influenced by construction factors. Based on previous studies, the parameter values used in this paper were as follows: 1.7 MPa for the onset stress of normal damage, 1.6 MPa for the onset stress of damage in the first and second tangential directions, 500 MPa/mm for normal stiffness, 150 MPa/mm for tangential stiffness in both directions, and 1.4 J/m2 for fracture energy39. Additionally, the CDP model was employed to capture the damage evolution process of the wide-narrow joint under axial loading.

This study primarily investigated the wide-narrow joint and interlayer damage under temperature loading through a fully coupled thermal-stress analysis using the C3D8T heat transfer element. Field observations revealed that the mortar layer and concrete base remained intact at the seam, with primary damage occurring at the wide-narrow joint and the interface between the track slab and the CA mortar layer. Therefore, during stress analysis, binding constraints were applied between the CA mortar layer and the concrete base, with the concrete base fully fixed at the bottom and symmetrical constraints applied to both sides of the model.

Validation of the model

To validate the accuracy of the established three-dimensional nonlinear numerical simulation model, this study compared the results of a 1:4 scaled-down model test conducted under extremely high-temperature conditions. The verification primarily evaluated structural performance. A 1:4 numerical simulation model was developed, maintaining material parameters, contact settings, and boundary conditions aligned with those employed in the previous study, as shown in Fig. 13. A comparative analysis of temperature conduction and track structure stress was performed to confirm the reliability of the parameters40.

In this study, the measured temperature values and longitudinal stress values obtained from the scaled-down test model under high-temperature conditions (40 °C) were compared with the calculated results of the established numerical simulation model, as shown in Fig. 14. As observed in Fig. 14a, the numerical simulation results show strong agreement with the temperature–time curve trends observed in the test results. The relative errors for the track slab, CA mortar, and concrete base were 4.2%, 2.6%, and 2.5%, respectively, with all relative errors remaining below 5%. Furthermore, the comparison of the longitudinal stress in the track structure indicates that the maximum relative error between the simulation and test values was 14%. This comparative analysis confirms the accuracy of the material and interface parameter values used in the simulation. It is important to note, however, that the CZM model discussed in this paper is specifically tailored to the CRTS II slab ballastless track system. The findings may not directly apply to other types of ballastless track structures, as the material properties of structural layers can differ significantly across systems.

Results and analysis

The predominant thermal load during summer was the overall temperature increase. Under these conditions, the CA mortar layer of the CRTS II slab ballastless track system suffered damage and degradation, primarily at the interface between the mortar layer and the track slab, and at the wide-narrow joint. Therefore, the overall temperature increase was adopted as the primary loading condition in this study. Notably, the temperature increase was measured relative to the track slab’s construction temperature. Based on practical worst-case scenarios and design specifications, the maximum temperature increase applied in the model was 60 °C. In the calculations and analysis presented in this section, temperature increases of 10 °C, 20 °C, 30 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C, and 60 °C were considered to examine the damage evolution at the interlayer interface and the wide-narrow joint between the track slabs.

Structural deformation characteristics

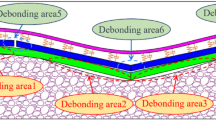

The three-dimensional nonlinear numerical simulation model of the CRTS II slab ballastless track, the typical up-arching behavior of the track structure under uniform temperature increase was observed, as shown in Fig. 15a. Further analysis indicated that up-arching predominantly occurred at the wide-narrow joint, as depicted in Fig. 15b. With increasing overall temperature, interface damage initiated at the edges of the track slab. As damage progressively expanded, the wide-narrow joint interface exhibited greater deterioration, leading to debonding at the joint ends and subsequent propagation toward the center, as shown in Fig. 15c.

Interlayer separation evolution law

The up-arching displacement of the track structure in the longitudinal direction was determined based on the calculation results under different temperature rise loads, as shown in Fig. 16. The results indicate that the up-arching displacement of the track structure increases with the overall temperature rise. Between 10 °C and 40 °C, the peak vertical displacement exhibited uniform increases, and the arch shape remains consistent. Additionally, the vertical displacement near the wide-narrow joints at the ends of the slab was comparatively smaller. At 50 °C and 60 °C, the vertical displacement of the wide-narrow joints and the track slab increased to 1.18 cm and 1.09 cm, respectively, and debonding occurred at the interlayer interface b near the slab ends. Notably, the vertical displacement at the wide-narrow joints increased sharply, aligning with the previously described interface bonding condition. This behavior was attributed to the increased axial force in the track slab during the warming process, leading to extrusion at the wide-narrow joints and significantly greater vertical displacement compared to the track end.

The analysis of the vertical displacement changes in the track structure under overall temperature rise reveals the up-arching deformation behavior of the system. To further investigate the evolution of interlayer separation, cloud diagrams of the interlayer separation displacements under various temperature rise conditions were generated from the analysis results, as shown in Fig. 17. The diagrams indicate significant differences in the interlayer separation behavior between the track slab and CA mortar layer across various temperature conditions. At the initial temperature rise, no significant interfacial separation displacement is observed. At 20 °C, interlayer separation initiates at the wide-narrow joint and propagates from the ends of the slab toward the middle as the temperature increases. At 60 °C, the interface becomes completely separated, as depicted in Fig. 18. The overall longitudinal distribution of interlayer separation values corresponds to the vertical displacement changes. Notably, no abrupt changes in interlayer separation were observed at the wide-narrow joints or the ends of the track slab, though a concave deformation develops in the middle of the narrow joint. This behavior occurs because axial force at the wide-narrow joint compresses the narrow joints, causing deformation at the bottom. Consequently, interlayer separation between the bottom of the narrow joints and the mortar layer at the ends of the slab was reduced.

The wide-narrow joint damage evolution

An analysis of previous studies indicates that the wide-narrow joint is a critical connection between the track slabs. This joint is susceptible to damage under axial force, and its integrity is crucial for the overall stability of the track structure. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the detailed damage evolution and specific damage locations of the wide-narrow joints under varying temperature increases.

Figure 19 presented the compressive damage distribution of the wide-narrow joint under different temperature rise conditions. At a temperature rise of 10 °C, the compressive damage at the wide-narrow joint was minimal, with no significant damage observed. However, Fig. 19a showed that the compressive damage values at the ends and middle of the wide-narrow joint, as well as the bottom of the narrow joints, were significantly higher than in other areas, indicating a greater likelihood of damage at these locations. At 20 °C, compressive damage gradually expanded toward the wide joint, with the maximum compressive damage at the bottom of the narrow joint reaching 0.648, as shown in Fig. 19b. At 30 °C, the maximum compressive damage at the bottom of the narrow joints increased to 0.71, followed by damage values of 0.54 and 0.48 at the junctions of the ends and the middle of the wide-narrow joints, as shown in Fig. 19c. At 40 °C, 50 °C, and 60 °C, the overall distribution of compressive damage remained similar, with the damage gradually spreading from the top of the wide joints to the belly of the joints, as depicted in Fig. 19d, e, and f.

To quantitatively analyze the overall damage evolution of the wide-narrow joint structure, and given that the joint’s irregular geometry induces stress concentrations under axial force, the wide-narrow joint was divided into five segments along the vertical direction of the transverse section. The wide joint was divided into section 1-1, 2-2, and 3-3, while the narrow joint was divided into sections 4-4, 5-5, and 6-6. Figure 20 illustrates the evolution of compressive damage distribution in different locations at various temperatures.

As shown in Fig. 20, the compressive damage values for different profiles of the wide-narrow joint reveal that the narrow joints undergo significantly greater deterioration than the wide joints. Additionally, due to the joint’s irregular structure, the vertical compressive damage exhibited transverse distribution patterns. The compressive damage in both the wide and narrow joints increased with rising temperatures. In Fig. 20a, the transverse compressive damage at the top of the wide joint (1-1) exhibited a concave distribution, characterized by greater damage at both ends relative to the middle, where the damage was slightly convex. The compressive damage varied significantly across different temperature rises. In the middle of the wide joint (2-2), damage was most pronounced in the protruding section, with the highest values at the ends, as shown in Fig. 20b. At the bottom of the wide joint (3-3), the damage values were smaller than at the top and middle, and no significant compressive damage detected in the central part, as shown in Fig. 20c. This analysis concluded that the middle and end positions of the wide joint were prone to compressive damage, and that the top section was particularly sensitive to temperature variations.

The development of compressive damage in the narrow joint was analyzed separately for its upper and lower positions. As shown in Fig. 20d, the damage distribution in the upper part (4-4) of the narrow joint was similar to that in the middle section of the wide joint, characterized by greater damage in the middle relative to the ends. Notably, during the overall warming from 10 °C to 20 °C, the compressive damage in the middle increased from 0.06 to 0.35, representing a nearly sixfold increase. From 20 °C to 30 °C, the damage increased from 0.35 to 0.53, a 1.5-fold increase. However, as the temperature continued to rise, the rate of increase in compressive damage gradually decreased. This suggested that the narrow joint was more temperature-sensitive in this interval, indicating a relatively high load-bearing capacity. As the temperature rose further, the load was shared by other parts of the wide and narrow joints, thereby reducing the load on the middle section and decelerating the rate of damage progression. As shown in Fig. 20e, the compressive damage in the lower part of the narrow joint (5-5) was significantly greater in the middle than at the sides. The structural geometry of the wide-narrow joints, particularly the raised parts on both sides of the narrow joint, caused stress concentrations, rendering these areas highly susceptible to compressive damage.

The tensile damage of the wide-narrow joint under various temperature rise conditions is illustrated in Fig. 21. The figure showed that tensile damage primarily occurred at the narrow joints. At a temperature rise of 10 °C, tensile damage initiated at the middle and ends of the narrow joints, with no significant damage observed in other areas. Due to the low tensile strength of concrete, as the temperature increased to 20 °C, more extensive tensile damage was observed at the lower protruding edges of the narrow joints. As the temperature continued to rise, the damage persisted at the lower edge of the narrow joints and gradually expanded to the surrounding areas, as indicated by the cloud diagram.

Similar to previous studies, the tensile damage evolution of each detailed structure within the wide-narrow joint was further examined by analyzing the joints along vertical sections. Due to the differences between tensile and compressive damage locations, the tensile damage analysis also included section 6–6. The tensile damage distribution across different cross-sections is depicted in Fig. 22. From Fig. 22a and b, the tensile damage in the upper and middle sections of the wide joint remained largely consistent throughout the warming process. The tensile damage did not vary significantly with increasing temperature, with a maximum value of only 0.15. Additionally, at the bottom of the wide joint, the tensile damage exceeded that observed in the upper sections. At a temperature rise of 60 °C, the tensile damage at both ends of the wide joint reached 0.7, while the middle concave section exhibited a tensile damage value of 0.2, as shown in Fig. 22c. Compared to the wide joints, the transverse tensile damage was more pronounced in the narrow joints. In the upper part of the narrow joints, the tensile damage at both ends of the concave structure exceeded that observed in the convex structure, as shown in Fig. 22d. Conversely, at the bottom of the narrow joint, the tensile damage at the ends of the concave structure exceeded that of the convex structure, as depicted in Fig. 22e. Based on the earlier analysis of the damage evolution cloud diagrams, the tensile damage was observed to be most severe along the bottom edge of the convex area. Therefore, this area was further analyzed, with the transverse tensile damage evolution depicted in Fig. 22f. From Fig. 22f, the tensile damage at the lower edge of the convex region exhibited oscillatory behavior. This fluctuation occurred because the data for the convex node position was derived from the tensile damage values at both the convex and narrow joint node positions, considering only the upper portion of the data in the analysis. The tensile damage value of 0.8 suggested that the lower edge of the convex region represented the region most susceptible.

In summary, axial forces under different temperature loads caused upward arching of varying degrees in the track structure, especially at the wide-narrow joint, and led to a gradual increase in the separation of the interlayer interface. This separation propagated from the wide-narrow joint toward the ends, eventually leading to complete interface debonding. Additionally, during the arching process, the wide-narrow joint was compressed by the ends of the track slab, rendering it more prone to damage. The analysis showed that the wide-narrow joint was an irregular structure subject to stress concentration due to its irregular geometry under axial force. Narrow joints were more vulnerable to damage than wide joints, with compressive damage concentrated at both ends and beneath the convex part of the narrow joints. Tensile damage was concentrated at the junctions of the wide and narrow joints and along the lower edge of the convex areas in the narrow joints.

Building on this analysis, the evolution mechanism of vertical instability in the track structure was further examined. Since the CRTS II slab ballastless track was a longitudinal ballastless track, the axial forces under temperature loads were significant, increasing the likelihood of vertical instability from upward arching. The process of upward arching was characterized by interlayer interface damage and degradation of the wide-narrow joint. Interface damage weakened the vertical constraints of the track structure, and failure of the wide-narrow joint resulted in structural collapse. Under axial force, eccentric loads easily formed, resulting in deformations that compromised initial design specifications and further diminished the structure’s resistance to deformation.

Engineering measures and recommendations

The findings of this study reveal that temperature loads significantly exacerbate interfacial damage and structural instability in the CRTS II slab ballastless track, particularly at wide-narrow joints. The process of upward arching under temperature loading not only weakens the vertical constraints of the structure but also leads to progressive interface separation and joint failure. To mitigate these adverse effects, several engineering measures and design recommendations are proposed: (i) Selecting materials with enhanced thermal stability and reduced thermal expansion can minimize stress accumulation under temperature fluctuations, improving overall structural integrity. (ii) Redesigning the geometry and material properties of the wide-narrow joints can help accommodate thermal deformation more effectively, reducing stress concentrations and joint damage. (iii) Thermal Control Strategies: Implementing measures such as thermal insulation or cooling systems can stabilize temperature fluctuations in extreme environments, protecting critical structural components. (iv) Advanced Monitoring Systems: Utilizing distributed optical fiber sensors for continuous monitoring allows for early detection of thermal damage and timely maintenance, preventing severe failures.

These measures not only address the challenges posed by temperature-induced damage but also provide a framework for improving the design, construction, and maintenance of ballastless track systems in high-speed railways. Incorporating these strategies can significantly enhance the durability and safety of such structures under varying environmental conditions.

Conclusions

This study investigated the interfacial mechanical properties of the track slab-CA mortar layer in the CRTS II slab ballastless track using a bilinear CZM integrated with a CDP model. Vertical full-scale static tests were performed to calibrate the CZM parameters and determine the bond-slip response, while a three-dimensional refined numerical simulation was developed to analyze the damage evolution of structural details under varying thermal conditions. The following conclusions are drawn:

-

(1)

The displacement and strain fields of the interface were quantified using the DIC test method, enabling accurate determination of CZM parameters. The identified damage onset displacement, failure displacement, and onset stress in the normal direction were 0.01789 mm, 0.06669 mm, and 0.19302 MPa, respectively, while the corresponding tangential values were 0.02448 mm, 0.07708 mm, and 0.26246 MPa. This precise characterization provides a robust framework for modeling interfacial behaviors in ballastless track systems.

-

(2)

The study revealed that under temperature loading, up-arching deformation of the track structure is concentrated at the wide-narrow joint. Interface damage initiates at the slab edges and progressively intensifies, leading to debonding at both ends of the wide-narrow joint. The study identifies this progressive debonding mechanism as a critical factor affecting structural integrity under thermal loads.

-

(3)

At elevated temperatures of 50℃ and 60℃, significant vertical displacements of 1.18 cm and 1.09 cm were observed at the wide-narrow joint and track slab, respectively. Complete debonding was evident at the interlayer interface near the slab ends, highlighting the vulnerability of these regions to thermal loads.

-

(4)

Structural geometry changes at the raised middle sections of narrow joints were found to induce stress concentrations, making these areas particularly susceptible to compressive damage. This insight underscores the importance of optimizing joint geometries to mitigate damage risks.

In this work, the primary focus is on the effects of temperature loads under static conditions to investigate interfacial mechanical properties and damage evolution. The effects of dynamic loads were not directly considered in the experimental or numerical analysis. However, we acknowledge the importance of dynamic loads in practical applications, and this will be considered in future studies as an extension of the current work.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Feng, Y. L. et al. Experimental investigation on shear steel bars in CRTS II slab ballastless track under low-cyclic reciprocating load. Constr. Build. Mater. 255, 119425 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Study on the interlayer debonding and its effects on the mechanical properties of CRTS II slab track based on viscoelastic theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 224, 387–407 (2019).

Chen, Z. Evaluation of longitudinal connected track under combined action of running train and long-term bridge deformation. J. Vib. Control. 26 (7–8), 599–609 (2020).

Su, M. et al. A brief review of developments and challenges for high-speed rail bridges in China and Germany. Struct. Eng. Int. 29 (1), 160–166 (2019).

Lou, P. et al. Experimental study on bridge—track system temperature actions for Chinese high-speed railway. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 18, 451–464 (2018).

Wang, D., Roesler, J. R. & Guo, D. Z. Analytical approach to predicting temperature fields in multilayered pavement systems. J. Eng. Mech. 135 (4), 334–344 (2009).

Chen, Z. et al. Deformation behavior of slab warping for longitudinal continuous rigid slab under temperature effect. Adv. Struct. Eng. 22 (13), 2823–2836 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Performance of cement asphalt mortar in ballastless slab track over high-speed railway under extreme climate conditions. Int. J. Geomech. 19 (5), 04019037 (2019).

Yusupov, B. et al. Characterization of vertical response of asphalt trackbed concrete in railway substructure to external loads. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1–12 (2020).

Zhou, L. Y. et al. Experimental study of the influence of extremely repeated thermal loading on a ballastless slab track-bridge structure. Appl. Sci. 10 (2), 461 (2020).

Zhou, R. et al. Experimental and numerical study on interfacial thermal behaviour of CRTS II slab track under continuous high temperatures. Eng. Struct. 284, 115964 (2023).

Song, A. et al. Experimental and Numerical investigations of Structural Performance of Slab Track under Hygrothermal Environment. Jordan J. Civil Eng., 17(1). (2023).

ČEBAŠEK, T. M. et al. Full scale laboratory testing of ballast and concrete slab tracks under phased cyclic loading. Transp. Geotechnics. 17, 33–40 (2018).

Vu, L., Jang, D. D. & Kang, Y. S. Assessment of structural dynamic response and vehicle-track interaction of precast slab track systems. Appl. Sci. 11 (8), 3558 (2021).

SadeghiI, J., Liravi, H. & Esmaeili, M. H. Experimental investigation on loading pattern of railway concrete slabs. Constr. Build. Mater. 153, 481–495 (2017).

Bose, T., Zania, V. & Levenberg, E. Experimental investigation of a ballastless asphalt track mockup under vertical loads. Constr. Build. Mater. 261, 119711 (2020).

Tarifa, M. et al. Full-scale fatigue tests of precast reinforced concrete slabs for railway tracks. Eng. Struct. 100, 610–621 (2015).

Chapeleau, X. et al. Study of ballastless track structure monitoring by distributed optical fiber sensors on a real-scale mockup in laboratory. Eng. Struct. 56, 1751–1757 (2013).

Zeng, Z. P. et al. Experimental study on evolution of mechanical properties of CRTS III ballastless slab track under fatigue load. Constr. Build. Mater. 210, 639–649 (2019).

Zhao, L. Spatial Refinement Analysis Method of High Speed Railway Ballastless Track and its Application Research (Beijing Jiaotong University, 2015).

Mahaboonpachai, T., Matsumoto, T. & Inaba, Y. Investigation of interfacial fracture toughness between concrete and adhesive mortar in an external wall tile structure. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 30 (1), 1–9 (2010).

Dai, G. & Su, M. Full-scale field experimental investigation on the interfacial shear capacity of continuous slab track structure. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 16, 485–493 (2016).

Du, W. et al. Adhesion performance tests and analysis of interface damage for CRTS III prefabricated slab tracks. Constr. Building Mater. 408, 133685 (2023).

He, L. et al. A novel fatigue cohesive model for interface between ballastless track slab and self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 377, 130962 (2023).

Wang, M. Z. et al. Experimental investigation on adhesive performance of concrete interface of double-block ballastless track based on cohesive zone model. J. China Railway Soc. 38, 88–94 (2016).

Su, C. et al. Experimental study on bond performances of track slab and mortar based on DIC technology. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 22 (9), 1–10 (2018).

Xu, Y. et al. Study on the mechanical performance and interface damage of CRTS II slab track with debonding repairment. Constr. Build. Mater. 257, 119600 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Push plate test of CRTS II slab ballastless track: theoretical analysis, experiments, and numerical simulation. Shock Vib. 1–12 (2021).

Cai, X. P. et al. Arching mechanism of the slab joints in CRTSII slab track under high temperature conditions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 98, 95–108 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Study on the interface damage of CRTS II slab track under temperature load. Structures 26, 224–236 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Damage mechanism of broad-narrow joint of CRTSII slab track under temperature rise. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 23, 2126–2135 (2019).

Zhou, R. et al. Structural damage analysis of CRTS II slab track with various interface models under temperature combinations. Eng. Fail. Anal. 134, 106029 (2022).

Su, C. et al. Experimental study on bond performances of track slab and mortar based on DIC technology. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 22, 3546–3555 (2018).

Mi, Y. et al. Progressive delamination using interface elements. J. Compos. Mater. 32 (14), 1246–1272 (1998).

Camanho, P. P., Davila, C. G. & De Moura, M. F. Numerical simulation of mixed-mode progressive delamination in composite materials. J. Compos. Mater. 37 (16), 1415–1438 (2003).

Krajcinovic, D. & Fonseka, G. U. The continuous damage theory of brittle materials, part 1: General theory. J. Appl. Mech. 48 (4), 809–815 (1981).

Zihu, F. et al. Choose of ABAQUS concrete stress-strain curve. Building Struct. 43 (S2), 559–561 (2013).

Birtel, V. & Mark, P. Parameterized finite element modeling of RC beam shear failure[C]//GADSTEIN M. 2006 ABAQUS Users´ Conference, UK, 95–108 (2006).

Ren, X. C. Research on Upwarp of CRTS II Ballastless Track slab end and its renovation (Beijing Jiaotong University, 2019).

Song, A. et al. Experimental study and numerical analysis of structural performance of CRTS II slab track under extreme high temperature. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. (2022).

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52178273), the Innovation and Development Joint Project of Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (Grant No. CSTB2023NSCQ-LZX0077), the Chongqing Talent Plan Project (Grant No. cstc2022ycjh-bgzxm0124), the Joint Training Base Construction Project for Graduate Students in Chongqing (Grant No. JDLHPYJD2020004), the Team Building Project for Graduate Tutors in Chongqing (Grant No. JDDSTD2022003), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0744).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anxiang Song: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Guowen Yao: Visualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation.Yuanchen Guo: Supervision, Validation, Resources. Gaofeng Zhang: Validation, Methodology. Xuanrui Yu: Supervision, Methodology, Investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, A., Yao, G., Guo, Y. et al. Study on interfacial mechanical properties and structural detail damage of CRTS II slab ballastless track. Sci Rep 14, 31354 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82822-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82822-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A condition diagnosis method for subway track structures employing distributed optical fiber sensing

Scientific Reports (2025)