Abstract

This study aims to assess the predictive value of certain markers of inflammation in patients with locally advanced or recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer who are undergoing treatment with anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) therapy. A total of 105 patients with cervical cancer, who received treatment involving immunocheckpoint inhibitors (ICIs), were included in this retrospective study. We collected information on various peripheral blood indices, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), and prognostic nutritional index (PNI). To determine the appropriate cutoff values for these inflammatory markers, we performed receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis. Progression-free survival (PFS) was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and we conducted both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to evaluate the prognostic value of these markers. Out of the 105 patients who received ICI treatment, the median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 19.0 months. We obtained the patients’ clinical characteristics, such as age, pathological type, therapy regimen, Figo stage, NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, and PNI from their medical records. The optimal cutoff values for NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, and PNI were determined as 3.76, 218.1, 3.34, 1147.7, 43.75, respectively. In the univariate analysis, age, pathological type, therapy regimen, Figo stage, and LMR were not found to be associated with PFS. However, high NLR(P=0.001), high PLR(P<0.001), high SII(P<0.001), and low PNI (P=0.003)were all associated with shorter PFS. Multivariate analysis indicated that SII (P=0.017) was an independent risk factor for PFS. This study highlights the potential use of SII as a predictor of progression-free survival in cervical cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer affecting women worldwide. It poses a serious threat to women’s health1. In 2020, there were approximately 604,000 new cases of cervical cancer globally. In China alone, there were nearly 110,000 new cases and 47,700 deaths from this disease. This accounted for approximately 18.3% of all global cases and 17.6% of all global deaths related to cervical cancer2. Despite the advancement of preventive HPV vaccines and effective screening and early detection methods, cervical cancer continues to be a significant burden worldwide. In cases of locally advanced cervical cancer, the standard treatment is platinum-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy, which has a 5-year survival rate ranging from 50–80%3,4. However, for advanced and metastatic cervical cancer, the 5-year survival rate drops dramatically to just 17%5.

In recent years, there have been significant breakthroughs in the treatment of cervical cancer with anti-PD-1 therapy. Studies such as KEYNOTE-1586 and CHECKMATE-3587 have demonstrated the effectiveness of pembrolizumab and nivolumab, respectively, as second-line treatments for cervical cancer. More recently, the results of the KEYNOTE-8268 study revealed that when used as a first-line treatment, pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy, with or without bevacizumab, significantly extends the overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced or metastatic cervical cancer. Additionally, the KEYNOTE-A189 study reported that, in cases of locally advanced cervical cancer, the combination of synchronous radiotherapy and chemotherapy with pembrolizumab greatly improves patient progression-free survival (HR = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.55–0.89; P = 0.0020). This represents a 30% reduction in the risk of disease progression. Based on these results, the FDA approved the combination of pembrolizumab with concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy as a treatment for newly diagnosed stage III-IVA cervical cancer patients.

However, it is important to note that not all patients benefit from immunotherapy. Currently, tumor tissue PD-L1 expression and tumor mutation burden (TMB) are widely accepted biomarkers for predicting the success of immunotherapy. Unfortunately, the clinical utility of these biomarkers is limited due to deviations in detection methods and expensive, uneven distribution of PD-L1 within tumors, and dynamic changes in PD-L1 expression in tumors. Additionally, the CLAP study showed that advanced cervical cancer patients can benefit from the combination of carlizumab and apatinib treatment, regardless of the PD-L1 status10. In a retrospective study of the real world, PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1 was not associated with OS of non-immunotherapy-treated patients with advanced cervical cancer11. However, only 25% of cervical cancer patients exhibit high TMB12. Hence, there is an urgent need to identify better predictive biomarkers. Inflammatory indicators are obtained through peripheral blood testing, which are easy to obtain, inexpensive and reproducible and can screen for patients who are most likely to benefit clinically.

The correlation between inflammation and tumors was first reported by Rudolf Virchow in 186313. Inflammation is a well-known characteristic of the tumor microenvironment, which can promote the occurrence, progression, and metastasis of tumors by inducing angiogenesis, cell proliferation, reactive oxygen species damaging DNA, and inhibiting cancer cell apoptosis14,15,16. Several studies have highlighted the predictive role of immune-inflammation systems, including the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), in various malignant tumors17,18,19. Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) is calculated based on serum albumin and circulating peripheral blood lymphocyte count and has been used to assess the immune nutritional status of cancer patients. PNI has also been proven to be an effective prognostic biomarker for various cancers, including cervical cancer20. However, the predictive role of these immune-inflammation systems and nutritional status in cervical cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy remains unclear. Therefore, we conducted this study to analyze the relationship between NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, PNI, and the short-term outcomes of patients with locally advanced or recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer who underwent anti-PD-1 treatment.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study included recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer patients and locally advanced cervical cancer patients in The Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University and Yancheng City No.1 People’s Hospital from February 2019 to February 2023.The patients were included as follows (a) ≥ 18 years old, (b) available clinicopathological and pretreatment laboratory data, (c) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) of 0 − 1, and at least one measurable lesion at baseline according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. (d) patients who underwent at least two cycles of immunotherapy, immunotherapy used until the disease progresses or maintained for one year. (e) received anti-PD-1 therapy with or without other therapy, anti-PD-1 therapy contained Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab, Sintilimab, Camrelizumab, Tislelizumab or Toripalimab, chemotherapy regimens contained cisplatin, carboplatin, paclitaxel and albumin bound paclitaxel. The exclusion criterion was as follows: patients with fever, systemic infammation, blood disease, immune disease, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events, or infection; withdrew immunotherapy because of intolerable toxicities, lacked follow-up data or received drugs that improved blood cell function within 2 weeks from the first dose of immunotherapy. According to these inclusion and exclusion criteria, 105 patients were finally enrolled in the study. The basic information of these patients was collected, including age, clinical stage, pathological classification, treatment regimen and hematological parameters. (Table 1). All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University and Yancheng City No.1 People’s Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study or their family.

Laboratory testing

The definition of each ratio is as follows: The NLR refers to the absolute neutrophil count divided by the lymphocyte count measured in peripheral blood, whereas the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) refers to the platelet count (cell/µL) divided by the lymphocyte count (cell/µL). The lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) refers to the lymphocyte count (cell/µL)divided by the monocyte count (cell/µL). PNI was calculated based on a peripheral blood sample and using the formula: serum albumin (g/L) + 5×peripheral blood lymphocyte count (×109 /L).SII was derived from platelet count (cell/µL)× neutrophil count (cell/µL)/lymphocyte count (cell/µL).

Follow up

PFS is defined as the time from PD-1 inhibitor treatment until disease progression or death or last follow-up. Patients were mainly followed up through medical record searches or telephone communications. The cut-off date was August 31, 2023.

Statistical analyses

All statistical tests were conducted using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).For descriptive analysis, continuous and categorical variables were expressed as medians (range) and percentages, respectively. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to identify the cut-off values of continuous variables. The Kaplan–Meier method was applied for survival analysis. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for univariate and multivariate analyses. Using statistically significant factors in univariate analysis for multivariate analysis. A forward selection stepwise procedure was applied for multivariate analysis. A two-sided p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients

A total of 105 patients with locally advanced, recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer treated with immunotherapy were enrolled in this study. The clinical characteristics of the patients, including age, BMI, albumin, pathological type, therapy regimen, and FIGO stage, were obtained from the medical records in Table 1. The median age was 57 years (ranging from 31 to 81 years). The median follow-up duration was 20 months (ranging from 2 to 44 months). Cervical squamous cell carcinoma accounted for most cases (95.2%), while cervical adenocarcinoma was observed in 4.8% of patient. 41% patients were locally advanced cervical cancer, 59% patients were recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer. All patients received combined treatment, including either 76.2% with chemoradiotherapy, 9.5% with radiotherapy, or 14.3% with chemotherapy. The median PFS was 19.0 months. The optimal cutoff values for NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, and PNI were determined as 3.76, 218.1, 3.34, 1147.7, 43.75, respectively. Other baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

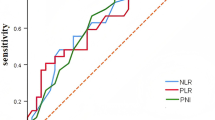

The Optimal Cut-Off Values for NLR, PLR, LMR, SII and PNI

As revealed in Fig. 1, the areas under the ROC curve for NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, and PNI were 0.663 (95% CI: 0.553–0.773), 0.675 (95% CI: 0.565–0.785), 0.549 (95% CI: 0.434–0.665), 0.702 (95% CI: 0.576–0.794), and 0.640 (95% CI: 0.530–0.750), respectively. The optimal cut-off values of NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, and PNI that predicted survival results were 3.76 (with a sensitivity of 0.615 and specificity of 0.697), 218.1(with a sensitivity of 0.692 and specificity of 0.682), 3.34(with a sensitivity of 0.379 and specificity of 0.744), 1147.7(with a sensitivity of 0.513 and specificity of 0.879), and 43.75(with a sensitivity of 0.712 and specificity of 0.564). According to the optimal cut-off values, patients were divided into high and low groups.

Survival analysis

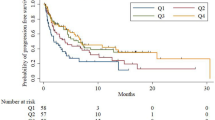

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to generate survival curves and the log rank test to compare the differences. Compared with the SII High group, patients before treatment in the SII Low group had longer PFS (P < 0.001, Fig. 2A). Compared with the NLR High group, patients before treatment in the NLR Low group had longer PFS (P < 0.001, Fig. 2B). Compared with the PLR High group, patients before treatment in the PLR Low group had longer PFS (P < 0.001, Fig. 2C). Compared with the PNI Low group, patients before treatment in the PNI High group had longer PFS (P = 0.002, Fig. 2D).

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses

The Cox proportional hazards regression model was applied to perform univariate and multivariate analyses of PFS. The results of univariate and multivariate analyses are presented in Table 2. In univariate analysis, we indicated age, pathological type, FIGO Stage, treatment and LMR was not related with PFS. Low SII(HR = 4.671, 95% CI = 2.457–8.879, P<0.001), Low NLR (HR = 3.139, 95% CI = 1.632–6.037, P = 0.001), Low PLR (HR = 3.804, 95% CI = 1.911–7.572, P<0.001) and High PNI (HR = 0.379, 95% CI = 0.200-0.719, P = 0.003) were related to longer PFS. However, the results of multivariate analyses displayed that NLR, PLR, PNI were not significantly risk factors for PFS, only Low SII (HR = 3.539, 95% CI = 1.256–9.976, P = 0.017) was independently associated with longer PFS.

Discussion

The majority of cervical cancer cases are caused by a persistent high-risk HPV infection21. Such persistent infections can integrate into the host genome, leading to the overexpression of the oncoproteins E6 and E7, thereby interfering with natural immune responses by downregulating key pathways22. Research has demonstrated that a persistent HPV infection upregulates the expression levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 in cervical cancer cells as well as in infiltrating immune cell23. One study found that 85% of patients with cervical cancer exhibit positive expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissues12. These findings underscore the potential therapeutic effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) for HPV-infected cervical cancer. Consequently, exploring biomarkers to predict the efficacy of ICIs is essential.

Clinical trials have demonstrated that PD-L1 expression, one of the most common predictive markers, cannot perfectly predict the efficacy of immunotherapy. Patients with low or negative PD-L1 expression can still benefit from monotherapy or combination immunotherapy. KEYNOTE-189 and KEYNOTE-407 have shown that, for PD-L1-negative non-small cell lung cancer, the combination of pembrolizumab and chemotherapy can improve PFS and OS compared to chemotherapy alone24,25. EMPOWER Cervical 1 compared the effects of cemiplimab monotherapy versus chemotherapy in advanced cervical cancer. In the overall population, the OS of the cemiplimab group was significantly longer than that of the chemotherapy group (12.0 months vs. 8.5 months) and the treatment reduced the risk of death by 31%. In the PD-L1-negative group, the ORR of the cemiplimab group was 11.4% (95% CI, 4-25%), while the chemotherapy group was only 8.3% (95% CI, 2.3-20.0%)26. The CheckMate 358 study evaluated the efficacy and safety of nivolumab ± ipilimumab in the treatment of recurrent and metastatic cervical cancer. The median follow-up time was 30.4 months, and the data indicated that regardless of the tumor PD-L1 status, lesion remission was observed in the nivolumab monotherapy, N3 + I1(nivolumab 3 mg/kg + ipilimumab 1 mg/kg), and N1 + I3(nivolumab 1 mg/kg + ipilimumab 3 mg/kg) groups27. The following reasons may account for this: firstly, due to the inherent bias of the detection methods, there is currently a lack of unified standards for detecting PD-L1 expression28. Secondly, the expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissues depends on their biological characteristics. PD-L1 expression is not uniformly distributed within the tumor; within the same tumor tissue, some parts may express positively while others may express negatively29. Thirdly, the expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissue is not sufficiently stable and is influenced by many molecular signals, which can undergo dynamic changes30. Therefore, the results of sampling at a specific time may not represent the overall PD-L1 expression level of the tumor tissue.

Previous studies have explored that inflammation is crucial in the occurrence and development of malignant tumors, and it also impacts the tumor immune microenvironment and treatment response31,32. Mingxia Cheng et al. reported an adverse association between NLR and prognosis in cervical cancer treated with combination immunotherapy33. Miaomiao Gou et al. have suggested that pre-treatment PLR correlated significantly with PFS and OS in gastric cancer patients who received immunotherapy34. Jingjing et al. found that pretreatment SII, NLR, and PLR are significant prognostic predictors of PFS and OS in advanced NSCLC patients receiving nivolumab35. In our study, univariable analysis indicated that pretreatment SII, NLR, and PLR were related to PFS in cervical cancer patients, but multivariate Cox analysis indicated that only SII is an independent prognostic factor for patients with cervical cancer(Table 2). Meanwhile, the ROC curve results showed that SII was more effective and accurate in predicting patient prognosis among these biomarkers (Fig. 1).The reason may be that compared to NLR and PLR, SII is composed of three types of blood cells, which is more comprehensive and can better reflect the body’s inflammation and immunity status. Therefore, SII may have more important clinical significance. In this study, univariate analysis showed a correlation between PNI and PFS, but multivariate analysis showed no correlation(Table 2). This may be due to that all patients included in this study received immunotherapy, which is different from the treatment methods used in previous studies. Furthermore, relevant clinical factors such as age and pathology show no significant correlation with prognosis. The reason may be that the majority of the study participants were older, and the pathological type was predominantly squamous cell carcinoma, which may introduce bias.

SII, which consists of neutrophil, platelet and lymphocyte, is a prognostic indicator for various malignant tumors36,37. This composite marker uses neutrophils and lymphocytes counting and platelets to quantify systemic inflammation and reflect the balance between host inflammation and immune status. Neutrophils can change tumor microenvironment through both external and internal pathways and then promote tumor cell proliferation and distant metastasis38. In addition, neutrophils are also one of the targets of tumor immunotherapy and participate in the ICI resistance mechanism39,40. Platelets can directly interact with tumor cells, activating tumors cytokine TGF- β and NF- β signal pathways that promote epithelial mesenchymal transition in tumors and tumor metastasis41. Besides, platelets can bind to tumor cells, protecting them from immune system attacks and then affecting the effectiveness of immunotherapy42. Several studies showed that the increase of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is associated with better efficacy and prognosis of immunotherapy in solid tumor patients43. Low lymphocyte counts can reduce the immune system, leading tumors occurrence and development44 and weakening the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Notably, 89% of cervical cancer patients will experience lymphocyte depletion after radiotherapy45. Therefore, both high NLR and high PLR were associated with worse prognosis. Elevated NLR and PLR together may imply a more intense inflammatory response and an underlying hypercoagulable state of the blood. In the tumor microenvironment, cytokines released by neutrophils activate platelets, which in turn promote neutrophil aggregation and activation, together promoting tumor cell growth. And lower SII, which is a combination of NLR and PLR, may benefit from cervical cancer with immunotherapy. Jiahong Yi studied that higher SII predicted worse outcomes in MSI-H mCRC patients undergoing immunotherapy46. De Giorgi et al. found that SII is one of the key prognostic factors for OS in patients receiving nivolumab treatment. Lower ORR and DCR are associated with higher baseline SII values, and SII ≥ 1375 can independently predict OS47. Nevertheless, the predictive role of SII in cervical cancer treated with combination immunotherapy has not been investigated. The results of our study indicated that pretreatment higher SII ≥ 1147.7 was significantly associated with worse PFS, which was independently predictive of inferior PFS in patients with cervical cancer after combination immunotherapy. At present, in the relevant research on inflammation indicators, most of the studies on cutoff values use the ROC curve method, which can show the sensitivity and specificity of the cutoff value of the results, and thus is more scientific and accurate, and has a better clinical utility value. Besides, the cut-off value for SII was similar to the value reported in the aforementioned studies.

Notably, single indicators of inflammation may have limitations in predicting prognosis. The multifactorial prediction model can combine several statistically significant predictive factors, making the prediction more accurate and meaningful. One study combined NLR, MLR, PNI, and albumin-alkaline phosphatase ratio (AAPR), to construct the Inflammation and Nutritional Prognostic Score (INPS), and the results showed that the INPS is an independent prognostic indicator for breast cancer48. Yang et al. found that LMR-NLR scoring system predicts prognosis in gliomas49. Therefore, constructing a multifactorial model based on multiple predictors may be a hot spot for future research on predictive markers of tumor immunotherapy efficacy and prognosis.

However, this study had some limitations. First, it is a retrospective study with a small number of patients, so a prospective study with a larger sample size should be needed to further validate the current conclusions. Second, this study lacks the detection of PD-L1 and it needs to be addressed by further research. Third, the optimal cut-off values of these indexes remain unknown. Finally, due to limitations in conditions, no overall survival data was obtained. We will conduct long-term follow-up to obtain the overall survival time.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that SII was an independent prognostic factor for cervical cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy. However, further large and multi-center prospective studies should be performed to confirm these findings.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Buskwofie, A., David-West, G. & Clare, C. A. A Review of Cervical Cancer: Incidence and Disparities. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 112, 229–232 (2020).

Shrivastava, S. et al. Cisplatin Chemoradiotherapy vs Radiotherapy in FIGO Stage IIIB Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 4, 506–513 (2018).

Hsu, H. C., Li, X., Curtin, J. P., Goldberg, J. D. & Schiff, P. B. Surveillance epidemiology and end results analysis demonstrates improvement in overall survival for cervical cancer patients treated in the era of concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 5, 81 (2015).

Tewari, K. S. et al. Bevacizumab for advanced cervical cancer: final overall survival and adverse event analysis of a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial (Gynecologic Oncology Group 240). Lancet. 390, 1654–1663 (2017).

Chung, H. C. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab in Previously Treated Advanced Cervical Cancer: Results From the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 1470–1478 (2019).

Naumann, R. W. et al. Safety and Efficacy of Nivolumab Monotherapy in Recurrent or Metastatic Cervical, Vaginal, or Vulvar Carcinoma: Results From the Phase I/II CheckMate 358 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 2825–2834 (2019).

Monk, B. J. et al. First-Line Pembrolizumab + Chemotherapy Versus Placebo + Chemotherapy for Persistent, Recurrent, or Metastatic Cervical Cancer: Final Overall Survival Results of KEYNOTE-826. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 5505–5511 (2023).

Lorusso, D. et al. Pembrolizumab or placebo with chemoradiotherapy followed by pembrolizumab or placebo for newly diagnosed, high-risk, locally advanced cervical cancer (ENGOT-cx11/GOG-3047/KEYNOTE-A18): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet. 403, 1341–1350 (2024).

Lan, C. et al. Camrelizumab Plus Apatinib in Patients With Advanced Cervical Cancer (CLAP): A Multicenter, Open-Label, Single-Arm, Phase II Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 4095–4106 (2020).

Baek, M. H. et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden in persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2024.35.e105 (2024).

Huang, R. S. P. et al. Clinicopathologic and genomic characterization of PD-L1-positive uterine cervical carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 34, 1425–1433 (2021).

Balkwill, F. & Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet Lond. Engl. 357, 539–545 (2001).

Ritter, B. & Greten, F. R. Modulating inflammation for cancer therapy. J. Exp. Med. 216, 1234–1243 (2019).

Singh, N. et al. Inflammation and cancer. Ann. Afr. Med. 18, 121–126 (2019).

Greten, F. R. & Grivennikov, S. I. Inflammation and Cancer: Triggers, Mechanisms, and Consequences. Immunity. 51, 27–41 (2019).

Guo, D. et al. A Novel Score Combining Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Parameters and Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Improves Prognosis Prediction in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients With Brain Metastases After Stereotactic Radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 12, 762230 (2022).

Zhou, K. et al. Prognostic role of the platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in the clinical outcomes of patients with advanced lung cancer receiving immunotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 12, 962173 (2022).

Fullerton, R. et al. Impact of immune, inflammatory and nutritional indices on outcome in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with definitive (chemo)radiotherapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 190, 291–297 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Prognostic effect of the pretreatment prognostic nutritional index in cervical, ovarian, and endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health. 24, 464 (2024).

Chen, Q. et al. Prognostic significance of negative conversion of high-risk Human Papillomavirus DNA after treatment in Cervical Cancer patients. J. Cancer. 11, 5911–5917 (2020).

Duensing, S. & Münger, K. Mechanisms of genomic instability in human cancer: insights from studies with human papillomavirus oncoproteins. Int. J. Cancer. 109, 157–162 (2004).

Wang, Y. & Li, G. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in cervical cancer: current studies and perspectives. Front. Med. 13, 438–450 (2019).

Garassino, M. C. et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 1992–1998 (2023).

Novello, S. et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Update of the Phase III KEYNOTE-407 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 1999–2006 (2023).

Tewari, K. S. et al. Survival with Cemiplimab in Recurrent Cervical Cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 386, 544–555 (2022).

Oaknin, A. et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer (CheckMate 358): a phase 1–2, open-label, multicohort trial. Lancet Oncol. 25, 588–602 (2024).

Doroshow, D. B. et al. PD-L1 as a biomarker of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 345–362 (2021).

Hirshoren, N. et al. Spatial Intratumoral Heterogeneity Expression of PD-L1 Antigen in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncology. 99, 464–470 (2021).

Luo, L. et al. Consistency Analysis of Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Expression between Primary and Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Study. J. Cancer. 11, 974–982 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Effects of immune cells and cytokines on inflammation and immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Int. Immunopharmacol. 88, 106939 (2020).

Rosenbaum, S. R., Wilski, N. A. & Aplin, A. E. Fueling the Fire: Inflammatory Forms of Cell Death and Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 11, 266–281 (2021).

Cheng, M., Li, G., Liu, Z., Yang, Q. & Jiang, Y. Pretreatment Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Lactate Dehydrogenase Predict the Prognosis of Metastatic Cervical Cancer Treated with Combination Immunotherapy. J Oncol 1828473 (2022). (2022).

Gou, M. & Zhang, Y. Pretreatment platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as a prognosticating indicator for gastric cancer patients receiving immunotherapy. Discov Oncol. 13, 118 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio can predict clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 33, e22964 (2019).

Zhou, Y., Dai, M. & Zhang, Z. Prognostic Significance of the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) in Patients With Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 12, 814727 (2022).

Wang, C., Jin, S., Xu, S. & Cao, S. High Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) Represents an Unfavorable Prognostic Factor for Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Etoposide and Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. Lung. 198, 405–414 (2020).

Coffelt, S. B. et al. IL-17-producing γδ T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 522, 345–348 (2015).

Valero, C. et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mutational burden as biomarkers of tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 12, 729 (2021).

Jaillon, S. et al. Neutrophil diversity and plasticity in tumour progression and therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 20, 485–503 (2020).

Haemmerle, M., Stone, R. L., Menter, D. G., Afshar-Kharghan, V. & Sood, A. K. The Platelet Lifeline to Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities. Cancer Cell. 33, 965–983 (2018).

Schmied, L., Höglund, P. & Meinke, S. Platelet-Mediated Protection of Cancer Cells From Immune Surveillance – Possible Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 12, 640578 (2021).

Gooden, M. J., de Bock, G. H., Leffers, N., Daemen, T. & Nijman, H. W. The prognostic influence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer. 105, 93–103 (2011).

Lin, E. Y. et al. Macrophages regulate the angiogenic switch in a mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 11238–11246 (2006).

Cho, O., Chun, M., Chang, S. J., Oh, Y. T. & Noh, O. K. Prognostic Value of Severe Lymphopenia During Pelvic Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in Cervical Cancer. Anticancer Res. 36, 3541–3547 (2016).

Yi, J., Xue, J., Yang, L., Xia, L. & He, W. Predictive value of prognostic nutritional and systemic immune-inflammation indices for patients with microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer receiving immunotherapy. Front. Nutr. 10, 1094189 (2023).

De Giorgi, U. et al. Association of Systemic Inflammation Index and Body Mass Index with Survival in Patients with Renal Cell Cancer Treated with Nivolumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 3839–3846 (2019).

Hua, X. et al. A Novel Inflammatory-Nutritional Prognostic Scoring System for Patients with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 381–394 (2022).

Yang, C. et al. Cumulative Scoring Systems and Nomograms for Predicating Survival in Patients With Glioblastomas: A Study Based on Peripheral Inflammatory Markers. Front. Oncol. 12, 716295 (2022).

Funding

The work was funded by the Grant (2020117) form the Gusu Health Talent Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S J and HW designed the study. QC extracted, collected and analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. BZ reviewed the results, interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. JL collected data and wrote the manuscript. HW, ZL, RS collected data and prepared tables and figures. YX drafted, revised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the fnal manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethical committee of The Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University and Yancheng City No.1 People’s Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Zhai, B., Li, J. et al. Systemic immune-inflammatory index predict short-term outcome in recurrent/metastatic and locally advanced cervical cancer patients treated with PD-1 inhibitor. Sci Rep 14, 31528 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82976-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82976-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Peripheral lymphocyte count as a prognostic marker in cervical cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a retrospective study

BMC Cancer (2025)

-

Prognostic significance of pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) in patients with cervical cancer: a meta-analysis

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2025)