Abstract

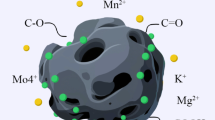

Recent extended summer seasons have presented considerable challenges for mushroom cultivation, underscoring the need for summer-adapted commercial varieties like Calocybe indica. The casing is essential for its cultivation, which conventionally employs loamy soil (LS). However, given the non-renewable nature of LS and the environmental concerns associated with spent mushroom substrate (SMS), our study explored SMS as a potential alternative. We analyzed the physio-chemical properties and microbial flora, especially bacterial composition, using MALDI-TOF in both LS and SMS. The total yield, biological efficiency, and mineral content of mushrooms grown on these substrates. While most of the physio-chemical properties of SMS align with the ideal casing properties, it exhibits higher electrical conductivity (EC) and a greater C/N ratio. The dominating bacterial flora in SMS, including Bacillus, Priestia, and Lysinbacillus, contribute to the mushrooms’ temperature tolerance and facilitate nutrient uptake, especially phosphorous (P). The yields and biological efficiency were significantly higher in LS, likely due to its superior mechanical support. Furthermore, the findings indicated that the qualities of element levels, particularly copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and phosphorous (P), were markedly elevated in mushrooms grown on SMS, except for iron (Fe). The PCA biplot results further supported these findings. The significantly elevated phosphorus (P) level in mushrooms grown in SMS highlights the role of phosphorous-solubilizing bacteria in SMS. Interestingly, Calocybe indica consistently exhibited higher iron (Fe) content than Pleurotus ostreatus, irrespective of the casing material used. The metal bioaccumulation factors (BCF) reveal that Calocybe indica is a hyperaccumulator of potassium (K) but does not bioaccumulate manganese (Mn). It also showed a low accumulation level of calcium (Ca) and iron (Fe), suggesting a synergistic interaction between Ca and Fe. In conclusion, LS proved more effective in maximizing yield, while SMS emerged as a sustainable alternative, enhancing the nutritional content of mushrooms and presenting a feasible choice for ecologically aware farming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mushroom cultivation epitomizes circular agriculture by employing low-value agricultural by-products such as rice straw, sawdust, cotton seed hull, and others to yield mineral and protein-rich food sources1,2,3. The successful cultivation of mushrooms relies on various exogenous factors such as temperature, precipitation, and light exposure intensity. Most popular varieties, such as Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus spp. are traditionally cultivated in subtropical regions during winter. However, the recent prolonged summer characterized by high temperatures and low precipitation has had a significant impact on mushroom cultivation, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions. Certain challenges arise for tropical edible mushrooms, such as Pleurotus djamor due to limited production capacity, Volvariella volvacea has a short shelf life of only 24 h at room temperature, and the jelly-like texture of Auricularia is not widely preferred. Consequently, this has prompted researchers to explore alternative varieties suited for warmer seasons.

The Milky Mushroom (Calocybe indica) was introduced by the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University in Coimbatore, India in 19984 and has emerged as a notable addition to summer mushroom varieties. This soil-dwelling hemicolous mushroom belongs to the Basidiomycete fungus family Tricholomataceae5,6. Flourishing in temperatures ranging from 30 to 38 °C with relative humidity is 70–80%, as highlighted by7,8. It has garnered recognition for its robust size, enticing milky white appearance, meat-like taste, extended shelf life (5–7 days at room temperature), and distinctive texture4,9. The cultivation of milky mushrooms involves a critical agronomic practice known as casing. This process entails covering the fully colonized mushroom substrate, serving as a pivotal step in transitioning from the vegetative to reproductive stages10. Casing is highlighted in numerous studies for its role in achieving high productivity, ensuring quality, and fostering uniformity in commercial cropping11,12,13. Furthermore, it serves as a vital layer for mushrooms by providing physical support, acting as a water reservoir, facilitating nutrient exchange, regulating osmotic pressure, enabling gas exchange, fostering an aerated environment for efficient metabolism, stimulating fructification, and providing zones for ion exchange14,15. Consequently, physiochemical factors of casing materials, such as water-holding capacity, porosity, pH, and types of microbial population, strongly influence the yield of mushrooms16,17.

In recent years, scholars have extensively researched the viability of various casing materials for milky mushroom cultivation, including loamy soil, cow dung, peat soil, spent mushroom substrates (SMS), and vermicompost15,18,19. While Loamy soil remains preferred in Bangladesh, its non-renewable nature necessitates consideration. Conversely, there is a rising interest in using spent mushroom substrate (SMS), particularly from oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.), as mushroom farming is gaining momentum in the country. Oyster mushrooms are primarily grown in Bangladesh using rice straw and sawdust. Our research is centered on repurposing SMS derived from oyster mushrooms cultivated on sawdust. Furthermore, extensive studies have explored the effect of casing material and microbial activities on various mushroom species such as Agaricus spp17,20,21, Phlebopus portentosus22, and Pleurotus spp.23, there’s a notable absence of research on the interaction between Calocybe indica and the microbial populations in casing materials.

Based on these facts, our investigation focused on assessing the physiochemical properties and microbial population of casing materials concerning the yield and qualities of Calocybe indica. The microbial abundance and composition of bacteria present in casing samples were analyzed employing a MALDI-TOF, and alpha diversity analyses were used for comparison between the samples. The results from these analyses are expected to offer valuable insights for developing effective and eco-friendly management strategies to produce quality mushrooms.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and analysis

The pure culture of milky white mushrooms (Calocybe indica) was obtained from the Mushroom Development Institute (MDI), Department of Agricultural Extension, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Rice straw served as a growing substrate for cultivating milky mushrooms, sourced from local farmers’ fields. The casing substrates, loamy soil (LS), and spent mushroom substrate (SMS) were collected from a local mushroom farm. The field experiment was conducted at MDI, while the analysis of casing substrate and mushroom qualities including mineral content, was performed at the Department of Life Sciences Laboratory and Plasma Plus Laboratory at Independent University Bangladesh. Bacterial identification through MALDI-TOF was carried out at the National Institute of Biotechnology (NIB), Savar, Bangladesh.

Preparation of mushroom spawn packets

Before being utilized, dried rice straw (RS) was cut into small pieces (3–5 cm in length) using a chaff cutter. The RS pieces were then fully hydrated by soaking them in tap water for 24 h, followed by pasteurization in a clean steel drum. The pasteurization process began by heating at 60 °C. The substrate was then added and kept in warm water for 30 min. Afterward, the substrate was spread on a plastic sheet over a sloped concrete surface to allow excess water to drain for 2–3 h, achieving a moisture level of 65–75%. For the subsequent step, a 1 kg spawn packet was prepared in polypropylene bags (35 × 17cm2) following the layer spawning method, with a seeding rate of 10% of the wet substrate. These bags were placed in a dark room with a controlled environment, maintaining a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C, humidity levels ranged 50–60%, and low light intensity (below 50 lux). Once the mycelium had fully colonized the substrate, the plastic bags were opened and transferred to the cropping room.

Preparation of casing materials and casing

The casing materials, LS and SMS, were pasteurized at 65 °C for 4 h, followed by a cooling period of 2–3 h. Once cooled, the pasteurized casing materials were uniformly applied in layers up to 3 cm thick over the fully colonized substrate18. Each treatment was replicated three times and arranged in a completely randomized fashion. Regular watering was conducted to maintain moisture levels between 70 and 80%, ensuring the casing layer was fully colonized with fungal mycelium.

Physicochemical properties analysis of casing materials

The physical and chemical properties of casing materials, including pH, water holding capacity (WHC), bulk density, particle density, electrical conductivity, and C/N ratio, were analyzed.

pH and electrical conductivity

The pH was analyzed in the aqueous extract, prepared by 1:10 (w/v) fresh substrates and deionized water, using a standard hydrogen electrode connected with a pH meter (model: pH 211, Hanna Instrument, Italy). Electrical conductivity (EC) was determined using a digital EC meter (Model Number: HI98312, HANNA DiST 6 EC/TDS/Temperature Tester High Range Italy).

Water holding capacity

The samples were desiccated in an oven before being placed in a container. The mass of the empty container was noted (Mc). The container was then filled with the desiccated samples, and the combined mass was recorded as Ms. The samples were saturated with water until dripping ceased. Afterward, the total mass of the container with the saturated samples was measured and documented as Mt. The mass of water (Mw) is calculated using the formula Mw = Mt – Ms, corresponding to the volume in milliliters (mL). Ultimately, water holding capacity (WHC) was calculated using the % WHC = Vt / Vw × 100 formula. Vw corresponds to the volume of water (Mw), whereas Vt signifies the volume of the saturated sample, which is equivalent to Mt.

Bulk density

The bulk density of casing materials was measured following the methods described by24. A 50 ml empty conical flask was weighed while empty. It was then filled with casing materials, gently tapped to ensure proper setting, and weighed again. Afterward, the casing material was removed, and the flask was filled with water using a graduated pipette to note the volume required to fill the flask completely. The bulk density was calculated using the formula Bulk Density: Mass of substrate (g) / Volume of container (cm3). Here, the mass of the substrate was obtained by subtracting the weight of the flask from the weight of the flask containing the casing materials.

Particle density

The particle density of samples, given in g/cm3, and measured according to25, is as follows: PD = Ms / Vp, where Ms denotes the mass of dry samples (g) and Vp represents the volume of sample particles (cm3). The particle volume was quantified using a pycnometer. Initially, the pycnometer was filled with water and dry samples, ensuring complete air displacement by gently swirling and measuring the volume of water displaced by the sample particles.

C/N ratio of substrates

The C/N ratio of the substrates was obtained based on the total nitrogen, determined by the Kjeldahl method, and the total carbon content that was determined by the dry ashing method26,27.

Data collection

Data were collected on several parameters: the number of days to primordia initiation, the number of days of the total harvest, the number of effective fruiting bodies (NEFB), the length and diameter of the stalk, the diameter and thickness of the pileus, the weight of the single fruiting body, the economic yield, and the biological efficiency (BE). The economical yield (g) was calculated after removing the stalks’ bases. Biological efficiency, a measure of the substrate’s conversion efficiency in mushroom cultivation, was determined by a ratio of biological yield harvested to the dry weight of the substrate in the formula: (Fresh weight of mushroom/ Dry weight of substrate) x 100. The experiment was repeated independently on three occasions, each with four replications.

Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess significant differences and mean values at the 5% significance level. One-way ANOVA was conducted utilizing SPSS software version 20 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States). The DMRT test for mean separation was utilized when ANOVA yielded significance (p < 0.05). A principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted utilizing an R program.

Bacterial identification using MALDI- TOF

Sample preparation

A small amount (1 µl) of bacterial cells was collected from a single colony with a sterile loop. This was then smeared thinly on a separate well of the target plate according to the spot plan and allowed to air dry at ambient temperature for 30 min. After drying, 1 µl of 70% folic acid was added to the sample. Once the folic acid had dried, 1 µl of HCCA matrix (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) was immediately overlaid on each sample well. The matrix was left to dry completely for several minutes before analysis with the MALDI-TOF MS (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry). The machine was calibrated with the standard BTS sample. MS and MS/MS spectra were obtained using a MALDI-QIT-TOF mass spectrometer (AXIMA Resonance, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) in the positive mode.

Determination of minerals content

Sample digestion

The substrates were oven-dried at 60 ± 2 °C until a constant weight was achieved. The dried samples were ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. For analysis, all mushroom samples were mineralized by the wet digestion method. Specifically, 0.5 g of powdered samples were placed into the Teflon vessels with 5 mL 65% nitric acid (Analar Grade, Merck, Germany) and 2 mL 30% hydrogen peroxide (Merck, Germany). The digestion process was carried out in a microwave digester (Model: Ethos One, Milestone, United States) at 180 °C for 45 min28. After digestion, the digests were transferred into 50 mL volumetric flasks and made up to volume with Class 1 (18MΩ) deionized water.

Analysis

The mineral elements sodium (Na), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn) were analyzed using Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (FAAS) following the method described by29. The FAAS instrument (Model: AA-7000, Shimadzu Co., Japan) was optimized for each metal, considering detection limits, wavelength (nm), cathode lamp current (mA) slit width (ranging from 0.2 to 0.7), and air-acetylene flame mixture, according to established literature. The standard recovery rates for the analytes ranged from 95 to 105%. Total phosphorus in the digested mushroom samples was determined using Visible Spectrophotometric (model: UV-1800, Shimadzu Co., Japan) through the ascorbic acid reduction method as outlined in USEPA Method 365.3.

Calculation of bio-concentration factor (BCF)

The Bio-concentration factor (BCF) was used to model the transfer of trace metals from casing materials to mushroom fruiting bodies. This method assumes a linear relationship between the metal concentrations in the casing substrate and the mushrooms. BCE is calculated according to30 using the equation: BCF = Metal in mushroom fruiting bodies/ Metal in casing substrate.

Results

Physical and chemical properties of the casing materials

The successful cultivation of hemiculous mushrooms, such as Calocybe indica, largely relies on the selection of appropriate casing materials. Table 1 showcases the physical and chemical properties of two casing materials, including SMS and LS. SMS demonstrated a pH value of 7.2, with water holding capacity (WHC) at 43.74%, a C/N ratio of 20.3, electrical conductivity (EC) of 4.05 mhos, bulk density (BD) of 0.22 g/cm3 and particle density (PD) at 0.53%. In comparison, LS had a pH value of 7.5, WHC at 30.41%, a C/N ratio of 11.6, EC of 0.37 mhos, BD of 0.16 g/cm3, and the same PD of 0.53. Remarkably, The results show that there were no significant differences between SMS and LS in terms of pH value and PD.

Bacterial communities of the casing materials

We examined the microbial population present in LS and SMS casing materials during the pinning stage of Calocybe indica. A prior study by31, reported that bacterial diversity within the casing substrate, especially the pinning stage, significantly influences the development of Agaricus bisporus fruiting bodies. To ensure accuracy and consistency, three biological replicates were conducted for each group. In total, 168 colonies were identified from SMS and 160 colonies from LS. The analysis identified three phyla: Firmicutes (57%), Proteobacteria (36%), and Flavobacteriun (7%), as shown in Fig. 1B. In addition, fourteen genera were detected, with Bacillus emerging as the dominant genus in both SMS and LS. However, the percentage distribution varied between the two materials: Bacillus, Priestia, and Lysinbacillus were dominant in SMS while Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Chrysobacterium were predominant in LS samples presented in Fig. 1C. Furthermore, the presence of Fictibacillus and Paenibacillus was found to be more abundant in only SMS. To compare the microbial diversity between SMS and LS samples, we calculated species diversity and richness using two different alpha diversity indices, including the Shannon index and Simpson index as presented in Fig. 1A. The median value of Simpson’s Diversity Index was 0.92 for SMS and 0.94 for LS. In the Box and Whiskers plot, the data for SMS displayed greater variability, evidenced by a wider interquartile range and whiskers, while being more tightly clustered around the median, suggesting consistent measurements across the samples. This plot highlights that SMS exhibits greater diversity in microbial populations. For the Shannon index, the median value was 2.72 for SMS and 2.78 for LS. The box plot indicates that LS has a slightly higher median value than SMS, reflecting a more diverse species composition in the LS habitat. However, both indices were statistically insignificant.

Time elapsed for pinhead initiation and total cropping period

The interim period for pin-head formation ranges from 14 to 16 days after casing. Interestingly, both SMS and LS substrates required approximately 16 days on average for pin-head development. In contrast, the cropping period showed a significant difference between these casing materials. Specifically, SMS had an extended cropping duration of 50 days, while LS demonstrated a shorter cropping period of 37.7 days presented in Fig. 2.

Effect of casing materials on the yield and biological efficiency of Calocybe indica

The results for the average weight of a single fruiting body (WSFB), economic yield (EY), and biological efficiency (BE) demonstrated significant variation (P < 0.05) among the tested treatments, which are illustrated in Fig. 3a, b. The significantly highest values were recorded with LS, yielding a WSFB of 47.48 g, an EY of 326.2 g, and a BE of 78.99%. Conservely, SMS produced a WSFB of 44.66 g, an EY of 295.67 g, and a BE of 71.59%.

Agronomical characteristics of fruiting bodies

The agronomical characteristics (yield attributes) of milky white mushrooms grown in various casing substrates are presented in Table 2. The results indicated that the length of the stipe (LS), diameter of the stipe (DS), diameter of the pileus (DP), and thickness of the pileus (TP) across the treatments varied in the ranges of 8.3–10.2, 2.5–2.7, 6.4–6.6, and 2.3–2.4 respectively. Interestingly, there was no significant difference observed in these parameters except for LS. Additionally, the total number of flushes (NFL) and the number of well-developed fruiting bodies per flush (NEFB) did not show any significant differences between SMS and LS.

Effect of casing materials on minerals content of mushroom

Mushrooms are widely recognized as a valuable source of trace elements with their mineral content varying depending on the growth substrate1. In the present study, rice straw was used as the primary growth substrate for both groups. We evaluated whether the mineral content of the mushroom was influenced by the casing materials used. We measured the macronutrient concentrations of sodium (Na), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), and magnesium (Mg), along with the micronutrients iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and manganese (Mn) on a dry weight basis as shown in Table 3.

The LS substrate contained the highest levels of most macro and micronutrients, except for K, Ca, and P, compared to SMS. Specifically, LS had the following average concentrations: Fe (22247.67 mg/kg) > Mg (10553.30 mg/kg) > K (7888.24 mg/kg) > Na (2950.00 mg/kg) > Ca (5308.66 mg/kg) > Mn (616. 67 mg/kg) > Zn (151.15 mg/kg) > P (141.13 mg/kg) > Cu (36.30 mg/kg). In contrast, the SMS contained K (8558.30 mg/kg) > Mg (3160.60 mg/kg) > Ca (8327.40 mg/kg) > Na (2419.67 mg/kg) > P (188.83 mg/kg) > Fe (112.81 mg/kg) > Zn (78.48 mg/kg) > Mn (78.66 mg/kg) > Cu (34.47 mg/kg).

Regarding the mineral content of mushroom fruiting bodies, those grown in LS exhibited the following average concentrations: K (30142.00 mg/kg) > Na (1800.09 mg/kg) > Mg (1129.00 mg/kg) > Fe (127.67 mg/kg) > Zn (60.59 mg/kg) > Ca (34.05 mg/kg) > Cu (17.97) > P (4.20 mg/kg). In comparison, mushrooms cultivated in SMS show the following pattern K (33,995.00 mg/kg) > Na (1186.33 mg/kg) > Mg (1140.67 mg/kg) > P (140.80 mg/kg) > Zn (67.26 mg/kg) > Fe (19.93 mg/kg) > Ca (30.39 mg/kg) > Cu (26.22 mg/kg). Surprisingly, Mn was recorded below the detection limit in mushroom fruiting bodies for both cases.

Bio-concentration factor

The bio-concentration factor (BCF) analysis assessing the uptake of trace elements by mushrooms from casing materials revealed a notable accumulation pattern in SMS K(3.97) > Zn (0.86) > Cu(0.76) > P(0.75) > Na(0.49) > Mg(0.36) > Fe(0.16) > Ca(0.004). At the same time, in LS, the BCF values were K (3.82) > Na ( 0.61) > Cu (0.49) > Zn (0.41) > Mg (0.11) > P (0.03) > Fe (0.006) > Ca (0.006). Strikingly, only the BCF value for K exceeded 1, while Ca and Fe showed the lowest BCF value in both cases as presented in Table 4.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

In the PCA biplot, the length of each vector represents the contribution of each character to the primary component, while the angle between vectors illustrates the relationships between variables. The angle between trait vectors provides insight into correlations: angles less than 90 ° indicate a positive correlation, while angles greater than 90° suggest a negative correlation. In this study, the PCA biplots presented in Fig. 4 demonstrate a clear distinction between the SMS and Soil casing groups, each influenced by different variables. The first principal component (PC1) is largely driven by mineral nutrients, with Cu, Zn, K, and P being significant for the SMS group, while Ca, Fe, and Na for the soil group show an opposite relationship. Strikingly, Ca and Fe show a strong correlation. The second component (PC2), while contributing less to the overall variance, is more associated with yield-attributing features. PC2 shows a positive association with NEL and NEFB and a negative association with TP and WFB.

Discussion

Calocybe indica (P&C) is highly suitable for cultivation in warm, humid tropical regions. This variety boasts a number of distinctive features, including a long shelf life, robust against mold and bacterial disease, an alluring white color, and a sustainable yield. The choice of casing substrate is crucial for successfully cultivating Calocybe indica, as it must meet specific criteria. According to previous studies, an ideal casing substrate should possess a porosity exceeding 50%, a WHC greater than 45%, EC below 1.6mhos, a pH up to 7.8, and a favored C/N ratio of 12:132,33,34. Within this framework, our study identified noteworthy variation (p < 0.05) in the physiochemical properties of SMS and LS. Specifically, SMS exhibited higher WHC, C/N ratio, BD, and EC, indicating a more nutrient-rich but potentially more compact and saline environment. In contrast, LS was characterized by faster nutrient release with lower water retention.

The analysis of the microflora, particularly the bacterial community within the casing substrates, sought to shed light on the role of casing bacteria in the production of Calocybe indica. Our findings demonstrated that the bacterial community predominantly consists of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria at the phylum level, aligning with the earlier research35,36,37. Additionally, distinct dominating bacterial species were identified across various casing substrates at the genus level. Notably, Bacillus, Priestia, and Lysinbacillus were found to be abundant in SMS, whereas Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Chrysobacterium were prevalent in LS. Noteworthy, Priestia megaterium (formerly Bacillus megaterium) emerged as a dominant bacterium in SMS materials, known for thriving at temperatures above 30 °C and enhancing plant growth by increasing free salicylic acid (SA) accumulation38. According to39, salicylic acid (SA) boosts hyphal growth in Pleurotus ostreatus under heat stress by modulating central carbon metabolism, redirecting glycolysis toward one-carbon metabolism, and generating ROS scavengers, which subsequently alter mitochondrial metabolism. In addition, SA can trigger the MAPK pathway and promote the synthesis of cell wall components. Moreover, Lysinbacillus fusiformis produces jasmonic acid40, which helps mitigate the heat stress in plants41. Both Priestia megaterium and Lysinbacillus fusiformis function as phosphorous-solubilizing bacteria, aiding in phosphorus (P) uptake. The presence of moderate halophytic bacteria, Fictibacillus halophilus, was observed in SMS, likely due to the high electrical conductivity (EC), which also leads to biosurfactant production.

There is no noticeable variation in the time required for pin-head development across different casing substrates, which typically ranges from 14 to 16 days. This timeframe for Calocybe indica has ranged from 12 to 30 days depending on the casing materials used42,43,44. Interestingly, the total harvest duration is significantly longer in SMS compared to LS. The high water holding capacity and elevated C/N ratio in SMS likely contributed to this extended harvest period. Since, mushrooms thrive in humid conditions, and the casing layer helps maintain moisture during the fruiting stage. Our study confirmed that the economic yield and biological efficiency significantly varied between the LS and SMS casing materials. Similar findings, where higher yield and biological efficiency were observed with soil, have been reported in other studies15,45. However, there was no significant difference in the yield-related characteristics except for the length of the stalk (LS). Several studies have reported that high environmental CO2 concentration increased the stalk length without impacting other traits46. This elevated CO2 in SMS is likely due to the heightened aerobic microbial activity in SMS.

Our results confirmed that casing materials play a crucial role in determining the mineral content of Calocybe indica. Specifically, for casing substrates, the average values of all elements, except for K, Ca, and P, were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in LS casing compared to SMS. Nevertheless, this difference was not mirrored in the elemental composition of mushroom fruiting bodies, as significantly higher values were observed in the fruiting bodies produced on SMS casing, except Fe. This discrepancy can likely be attributed to the high water-holding capacity and greater microbial activity in the SMS substrate. Generally, nutrient availability is closely tied to their solubility and mobility, which are heavily influenced by the moisture level of the substrate and the activity of microorganisms. Bacteria and fungi, for instance, are essential in breaking down organic matter and mineralizing nutrients, thereby making them accessible to plants. On top of them, minerals in soil are supposed to be biologically unavailable for Calocybe indica since nutrient elements in soil exist in various forms, including ions, organic compounds, and mineral particles.

The predominant macronutrients found in fruiting bodies of Calocybe indica are Na, K, Mg, and P, consistent with the findings of47. However, the Ca content is relatively low, ranging from 30.39 to 34.05 mg/kg, similar results were also observed in Pleurotus ostreatus48. Surprisingly, the P content was significantly higher in mushrooms grown on SMS than in LS which possibly attributed to more phosphorous solubilizing bacteria were observed in SMS. A notable variation in micronutrient content was observed, particularly for Zn, Cu, and Fe, with levels ranging from 60.59 to 67.26 mg/kg, 17.97–26.22 mg/kg, and 19.93 -127.67 mg/kg respectively. Remarkably, Mn was undetectable in the fruiting bodies, indicating that Calocybe indica does not bioaccumulate Mn. Furthermore, a substantial amount of Fe is found in mushrooms growing on LS but not in SMS. Although the Fe content in Calocybe indica regardless of the casing substrate is considerably higher than that reported for Pleurotus ostreatus by48 at 9.66 mg/kg, and49 at 15.20 mg/kg. Importantly, Calocybe indica contains a higher amount of minerals than Pleurotus ostreatus and Agaricus bisporous which fall within acceptable nutritional levels for human consumption shown in Table 5.

The minerals elements trends for the bioconcentration factor (BCF) in Mushrooms grown in SMS followed the order of K > Zn > Cu > P > Na > Mg > Fe > Ca, while for mushrooms grown in LS, the BCF pattern was K > Na > Cu > Zn > Mg > P > Fe and Ca. As noted by53, and54, the accumulation of trace metals in mushrooms is influenced by both biological factors, such as species, physiology, and phenology, and non-biological factors including temperature, seasons, salinity, and pH. Additionally, the differences in values of BCF could be correlated to the trace metal interactions which can originate from conflicting and synergetic processes55. In this study, Calocybe indica exhibited a BCF of less than one for all analyzed trace metals, except potassium (K), suggesting that this mushroom is a hyperaccumulator of potassium. Captivatingly, the BCF values for Ca and Fe were consistently low, indicating that Calocybe indica are not efficient at absorbing Ca and Fe, aligned with the observation of56,57. This finding also highlights a synergistic relationship between Ca and Fe. In contrast, the accumulation of Zn and Cu in Calocybe indica was relatively high compared to other micronutrients. This could be attributed to the presence of phytochetatins in the fruiting bodies, which likely facilitates the uptake of these metals. According to58, phytochelatins are commonly found in most eukaryotic cells and some prokaryotes tend to form complexes with transition metals like Zn and Cu. However, the overall BCF values in SMS are remarkably higher than those in LS, except for Na, suggesting that SMS casing is more suitable for Calocybe indica in terms of mineral nutrient uptake.

Conclusion

Calocybe indica is a promising mushroom species for summer cultivation, particularly well-suited for the Sahara and Sub-Sahara regions. Traditionally, loamy soil has been used as a casing material, but it is a non-renewable resource. Spent mushroom substrate (SMS) presents a potential alternative, offering microbial advantages and mineral-rich mushrooms, although it tends to result in a lower biological yield compared to loamy soil. More research is needed to understand the reasons behind the reduced yield when using SMS. Future studies should explore innovative strategies, such as combining SMS with organic and inorganic materials, to create an optimal casing formulation with maximizes yield.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Ahmed, R. et al. Optimizing tea waste as a sustainable substrate for oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) cultivation: a comprehensive study on biological efficiency and nutritional aspect. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 7, 1308053. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1308053 (2024).

Odediran, F. A. et al. Contribution of mushroom production to rural income generation in Oyo State, Nigeria. FUTY J. Environ. 14 (3), 47–54 (2020).

Nanje Gowda, N. E. & Chennappa, G. Mushroom cultivation: a sustainable solution for the management of agriculture crop residues. Recent advances in mushroom cultivation technology and its application15–26 (Bright Sky, 2021).

Subbiah, K. A. & Balan, V. A comprehensive review of tropical milky white mushroom (Calocybe indica P&C). Mycobiology 43 (3), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.5941/MYCO.2015.43.3.184 (2015).

Kumar, S., Sharma, V. P., Shirur, M. & Kamal, S. Status of Milky mushroom in India-a review. Mushroom Res. 26 (1), 21–39 (2017).

Kumar, V., Valadez-Blanco, R., Kumar, P., Singh, J. & Kumar, P. Effects of treated sugar mill effluent and rice straw on substrate properties under milky mushroom (Calocybe indica P&C) production: Nutrient utilization and growth kinetics studies. Environ. Technol. Innov. 19, 101041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2020.101041 (2020).

Vijaykumar, G., John, P. & Ganesh, K. Selection of different substrates for the cultivation of milky mushroom (Calocybe indica P & C). Int. J. Knowl. Transf. 13 (2), 434–436 (2014).

Kumar, R., Singh, G., Pandey, P. & Mishra, P. Cultural, physiological characteristics and yield attributes of strains of milky mushroom (Calocybe indica). J. Mycol. Plant. Pathol. 41 (1), 67–71 (2011).

Chang, S. T. Mushroom cultivation using the ZERI principle: potential for application. Micologia aplicada Int. 19 (2), 33–34 (2007).

Vieira, F. R. & Pecchia, J. A. Bacterial community patterns in the Agaricus bisporus cultivation system, from compost raw materials to mushroom caps. Microb. Ecol. 84 (1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-021-01833-5 (2022). Epub 2021 Aug 12. PMID.

Pardo-Giménez, A., Carrasco, J., Pardo, J. E., Álvarez-Ortí, M. & Zied, D. C. Influence of substrate density and cropping conditions on the cultivation of sun mushroom. Spanish J. Agric. Res. 18(2), 0902. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2020182-16037 (2020).

Yang, R. H. et al. Bacterial profiling and dynamic succession analysis of Phlebopus portentosus casing soil using MiSeq sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1927. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01927 (2019).

Carrasco, J. & Preston, G. M. Growing edible mushrooms: a conversation between bacteria and fungi. Environ. Microbiol. 22 (3), 858–872. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14765 (2020).

Kacprzak, M. et al. Sewage sludge disposal strategies for sustainable development. Environ. Res. 156, 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.010 (2017).

Sardar, H. et al. Effect of different agro-wastes, casing materials and supplements on the growth, yield and nutrition of milky mushroom (). Folia Horticulturae. 32 (1), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.2478/fhort-2020-0011 (2020).

Pardo, A., Pardo, J. E., de Juan, J. A. & Zied, D. C. Modelling the effect of the physical and chemical characteristics of the materials used as casing layers on the production parameters of Agaricus bisporus. Arch. Microbiol. 192 (12), 1023–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-010-0631-3 (2010).

Wang, Y. H. et al. Influence of the casing layer on the specific volatile compounds and microorganisms by Agaricus bisporus. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1154903. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1154903 (2023).

Amin, R., Khair, A., AIam, N. & Lee, T. S. Effect of different substrates and casing materials on the growth and yield of Calocybe indica. Mycobiology 38(2), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.4489/MYCO.2010.38.2.097 (2010).

Ashrafi, R., Mian, M. H., Rahman, M. M. & Jahiruddin, M. Reuse of spent mushroom substrate as casing material for the production of milky white mushroom. 15(2), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.3329/jbau.v15i2 (2017).

Kertesz, M. A. & Thai, M. Compost bacteria and fungi that influence growth and development of Agaricus bisporus and other commercial mushrooms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 1639–1650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-8777-z (2018).

Carrasco, J. et al. Holistic assessment of the microbiome dynamics in the substrates used for commercial champignon (Agaricus bisporus) cultivation. Microb. Biotechnol. 13 (6), 1933–1947. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.13639 (2020). Epub 2020 Jul 27. PMID: 32716608; PMCID: PMC7533343.

Yang, R-H. et al. Bacterial Profiling and Dynamic Succession Analysis of Phlebopus portentosus Casing Soil Using MiSeq Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 10: doi: (1927). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01927 (2019).

Kong, W. et al. Metagenomic analysis revealed the succession of microbiota and metabolic function in corncob composting for preparation of cultivation medium for Pleurotus ostreatus. Bioresour. Technol. 306, 123156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123156 (2020).

Singh, R. A. Soil physical analysispp 321–325 (Kalyani, 1980).

Blake, G. R. Particle density. In: (ed Chesworth, W.) Encyclopedia of Soil Science. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020- 3995–9406 (2008).

Kalra, Y. Handbook of Reference Methods for Plant Analysis (CRC, 1997).

Sáez-Plaza, P., Navas, M., Wybraniec, S., Michałowski, T. & Agustin Garcia Asuero An Overview of the Kjeldahl Method of Nitrogen Determination. Part II. Sample Preparation, Working Scale, Instrumental Finish, and Quality Control. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2012.751787 (2013).

Lao, Y. M., Qu, C. L., Zhang, B. & Jin, H. Development and validation of single-step microwave-assisted digestion method for determining heavy metals in aquatic products: Health risk assessment. Food Chem. 402, 134500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134500 (2023).

Brzezicha-Cirocka, J., Grembecka, M., Grochowska, I., Falandysz, J. & Szefer, P. Elemental composition of selected species of mushrooms based on a chemometric evaluation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 173, 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.02.036 (2019).

Galal, T. M., Gharib, F. A., Ghazi, S. M. & Mansour, K. H. Metal uptake capability of Cyperus articulatus L. and its role in mitigating heavy metals from contaminated wetlands. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 21636–21648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-9793-8 (2017).

Nienke, B., Margot, C., Koster, Han, A. B. & Wösten Beneficial interactions between bacteria and edible mushrooms. Fungal Biology Reviews. 39 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbr.2021.12.001 (2022). Pages 60–72, ISSN 1749–4613.

Zied, D. C., Pardo-González, J. E. & Minhoni, M. T. A. Pardo-Giménez, A. A reliable quality index for mushroom cultivation. J. Agric. Sci. 3 (4), 50–61 (2011).

Peyvast, G. H., Shahbodaghi, J., Remezani, P. & Olfati, J. A. Performance of tea waste as a peat alternative in casing materials for bottom mushroom (Agaricus bisporus (L.) Sing.) cultivation. Biosci. Biotech. Res. Asia. 4, 1–6 (2011).

de Gier, J. F. A different perspective on casing soil. In: Science and Cultivation of Edible Fungi (Van Griensven. ed.) Balkema Rotterdam, 931 – 34 (2000).

Pecchia, J. O. H. N., Cortese, R. & Singh, M. Investigation into the microbial community changes that occur in the casing layer during cropping of the white button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Mushroom Biology and Mushroom Products. New Delhi, India, 309–313 (2014).

Wang, M., Fan, X., Ding, F. & Jasmonate A Hormone of Primary Importance for Temperature Stress Response in Plants. Plants 12, 4080. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12244080 (2023).

Carrasco, J. & Preston, G. M. Growing edible mushrooms: a conversation between bacteria and fungi. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 858–872. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14765 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. A plant growth-promoting bacteria Priestia megaterium JR48 induces plant resistance to the crucifer black rot via a salicylic acid-dependent signaling pathway. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1046181. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1046181( (2022).

Hu, Y. R. et al. Salicylic acid enhances heat stress resistance of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm through metabolic rearrangement. Antioxidants 11 (5), 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11050968 (2022). PMID: 35624832; PMCID: PMC9137821.

Zhu, L., Guo, J., Sun, Y., Wang, S. & Zhou, C. Acetic acid-producing endophyte Lysinibacillus fusiformis orchestrates jasmonic acid signaling and contributes to repression of cadmium uptake in tomato plants. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 670216. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.670216 (2021). PMID: 34149767; PMCID: PMC8211922.

Wang, Y-H. et al. Influence of the casing layer on the specific volatile compounds and microorganisms by Agaricus bisporus. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1154903. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1154903 (2023).

Chinara, N. & Mahapatra, S. S. Evaluation of casing materials on productivity of milky mushroom (Calocybe indica P&C). Mushroom Res. 31 (2), 167–170 (2022).

Kerketta, A., Pandey, N. K., Singh, H. K. & Shukla, C. S. Effect of Straw Substrates and Casing Materials on Yield of Milky Mushroom (Calocybe indica P&C.) Strain CI-524. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App Sci. 7 (02), 317–322. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.702.041 (2018).

Alam, N., Amin, R., Khair, A. & Lee, T. S. Influence of Different Supplements on the Commercial Cultivation of Milky White Mushroom. Mycobiology 38 (3), 184–188. https://doi.org/10.4489/MYCO.2010.38.3.184 (2010).

Krishnamoorthy, A. S. & Priyadharshini, B. Physical, Chemical and Biological Properties of Casing Soil Used for Milky Mushroom (Calocybe indica P&C) Production, Madras Agric. J 103 (10–12), 338–343. https://doi.org/10.29321/MAJ.10.001045 (2016).

Patil, R. et al. Unlocking the growth potential: harnessing the power of synbiotics to enhance cultivation of Pleurotus spp. J. Zhejiang Univ. -Sci B. 25 (4), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B2300383 (2024).

Chelladurai, G., Yadav, T. K. & Pathak, R. K. Chemical composition and nutritional value of paddy straw milky mushroom (Calocybe indica). Nat. Environ. Pollution Technol. 20 (3), 1157–1164 (2021).

Effiong, M. E., Umeokwochi, C. P., Afolabi, I. S. & Chinedu, S. N. Assessing the nutritional quality of Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom). Front. Nutr. 10, 1279208. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1279208 (2024).

Irshad, A. et al. Determination of Nutritional and Biochemical Composition of Selected Pleurotus spps. BioMed Research International, 8150909. (2023). (1) https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/8150909 (2023).

Mohiuddin, K. M., Alam, M. M., Arefin, M. T. & Ahmed, I. Assessment of nutritional composition and heavy metal content in some edible mushroom varieties collected from different areas of Bangladesh. Asian J. Med. Biol. l Res. 1 (3), 495–501 (2015).

Paulauskienė, A., Tarasevičienė, Ž., Šileikienė, D. & Česonienė, L. The quality of ecologically and conventionally grown white and brown Agaricus bisporus mushrooms. Sustainability 12 (15), 6187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156187 (2020).

FAO. Human vitamin and mineral requirementsvol. 303 (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2001).

Ediriweera, A. N. et al. Ectomycorrhizal mushrooms as a natural bio-indicator for assessment of heavy metal pollution. Agronomy 12 (5), 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12051041 (2022).

Ndimele, C. C., Ndimele, P. E. & Chukwuka, K. S. Accumulation of heavy metals by wild mushrooms in Ibadan, Nigeria. J. Health Pollution. 7 (16), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.5696/2156-9614-7.16.26 (2017). PMID: 30524837; PMCID: PMC6221449.

Yang, X. E. et al. Cadmium tolerance and hyperaccumulation in a new Zn-hyperaccumulating plant species (Sedum alfredii Hance). Plant. Soil. 259, 181–189 (2004).

Lee, C. Y., Park, J. E., Kim, B. B., Kim, S. M. & Ro, H. S. Determination of mineral components in the cultivation substrates of edible mushrooms and their uptake into fruiting bodies. Mycobiology 37 (2), 109–113. https://doi.org/10.4489/MYCO.2009.37.2.109 (2009).

Golian, M. et al. Accumulation of Selected Metal Elements in Fruiting Bodies of Oyster Mushroom. Foods 11 (1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11010076 (2022). (2022).

Clemens, S. Evolution and function of phytochelatin synthases. J. Plant Physiol. 163 (3), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2005.11.010 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author as the supervisor is grateful to the Mushroom Development Institute (MDI) for providing mushroom germplasm and supported the field experiment, Plasma Plus Laboratory of the Pharmacy Department at Independent University Bangladesh, for conducting mineral analysis, to the National Institute of Biotechnology (NIB) for performing the MALDI-TOF analysis, and to the Krishi Gobesona Foundation (KGF) for providing financial support.

Funding

This research was funded by Krishi Gobesona Foundation (KGF) Bangladesh grant numbers (CN/FRPP): TF141-C/23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RB, MHM, and MAG conducted the experiment; SME, SY, and MSI analyzed the data, reviewed and edited various drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final version. TF and JK supervised the entire project, drafted the manuscript, and prepared the final version. All authors have reviewed and approved the published manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statements

Our research did not include any human subjects or animal experiments.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bashir, R., Mahi, M.H., Ferdous, T. et al. Using spent mushroom substrate (SMS) as a casing boosted bacterial activity and enhanced the mineral profile of the Calocybe indica. Sci Rep 15, 26945 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83015-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83015-0